Geoinformatics Cyberinfrastructure For The Solid Earth Sciences 1st Edition G Randy Keller

Geoinformatics Cyberinfrastructure For The Solid Earth Sciences 1st Edition G Randy Keller

Geoinformatics Cyberinfrastructure For The Solid Earth Sciences 1st Edition G Randy Keller

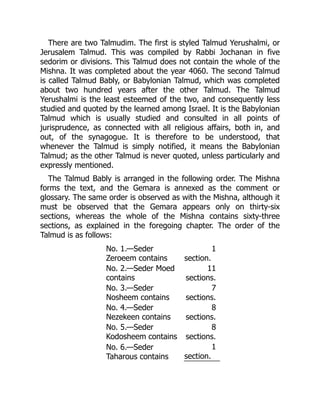

![seven complete years, the lunar and solar years then agree, without

any variation whatever.[A] Hence it is that the Jewish calculation is

very exactly and astronomically contrived, for it has never failed

since its first introduction, now nearly fifteen centuries. This is a

sufficient proof that the science of astronomy was known to the

ancient Israelites.

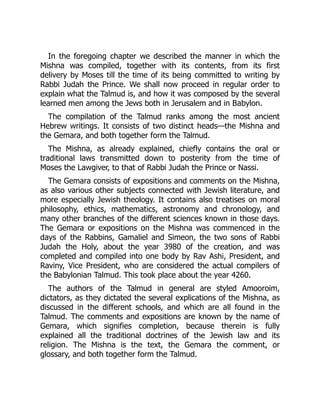

We have already stated, that the Talmud contains many allegories,

aphorisms, ethics, etc., which, it must be observed, are not to be

interpreted in their literal sense, but as being intended to convey

some moral and instructive lesson,—such being the system peculiar

to oriental nations. This system not having been clearly understood

by many of the Jews and Gentiles in both ancient and modern times,

has led to the belief that the whole of the Talmud, as it now exists,

is of divine origin. Now in justice to the authors of the Talmud, it

must be stated, that they never intended to convey any such idea;

their object was simply to render their discussions and dissertations

intelligible to their coreligionists of those days, and that it should be

carefully handed down to posterity. With this view it was, that the

compilers of the Talmud left the work in its original and genuine

state, with all the arguments and disputations as given by the

authors in the various ages, so that they might not be charged with

having interpolated it with ideas of their own, foreign to the views

and intentions of the original authors of the work. This is sufficient

to show that the whole of the Talmud never was considered by the

learned, as having a divine origin; but those portions of the Mishna,

illustrative of the written law, as already explained, were received as

divine, having been successively transmitted by oral tradition, from

Moses to Rabbi Judah, the Prince, and by him placed before the

world and handed down unalloyed to succeeding generations. In

coming ages, the learned among Israel, desirous that the study of

the Talmud should not be entirely lost, have added comments and

glossaries, in order to render the work as easy as possible to the

comprehension of the student. The Talmud contains, not, as has

been said, the narrow-minded sentiments of bigots, but the devout

and conscientious discussions of men deeply impressed with the love](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1245031-250518112102-e343e446/85/Geoinformatics-Cyberinfrastructure-For-The-Solid-Earth-Sciences-1st-Edition-G-Randy-Keller-69-320.jpg)

![were made by Catholics, ere they proceed in their attacks upon a

work which could command such expressions from those whose

religion was so widely different, but whose reason could not refuse

to yield to the cogent proofs the divine book in itself contained.

FOOTNOTES:

[A] See the end of the book for an explanation of the Jewish

months and years.

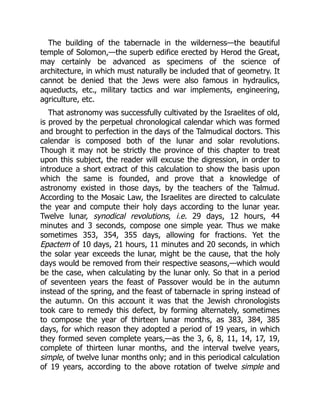

OF THE JEWISH MONTHS AND YEARS.

Time is the duration of things; it is divided into years, months,

weeks, days, hours, minutes, and seconds. A year is the space of

twelve months, which is the time the sun takes in passing through

the twelve signs of the Zodiac. The Zodiac is a circle showing the

earth's yearly path through the heavens. On this circle are marked

the twelve signs, which are numbers of stars, reduced by the fancy

of men into the form of animals, and from these forms they take

their name. A month is the time the moon occupies in going round

the earth. There are two kinds of months, Lunar and Solar. Lunar

months are calculated by the moon; solar months are reckoned by

the sun. The Hebrews make use of lunar months which consist](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1245031-250518112102-e343e446/85/Geoinformatics-Cyberinfrastructure-For-The-Solid-Earth-Sciences-1st-Edition-G-Randy-Keller-72-320.jpg)