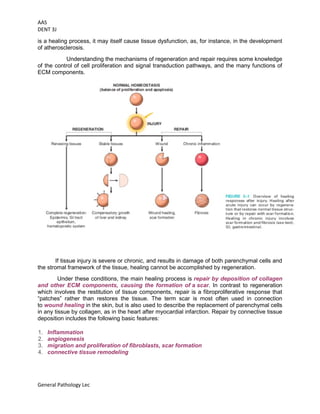

This document provides an overview of cell injury and death, outlining the mechanisms and causes of reversible and irreversible injury, including necrosis and apoptosis. It discusses the factors influencing cell response to injury, such as genetic variations and types of stimuli, as well as the morphological changes the cells undergo. The document also details the physiological and pathological roles of apoptosis in eliminating damaged or unneeded cells without provoking inflammation.