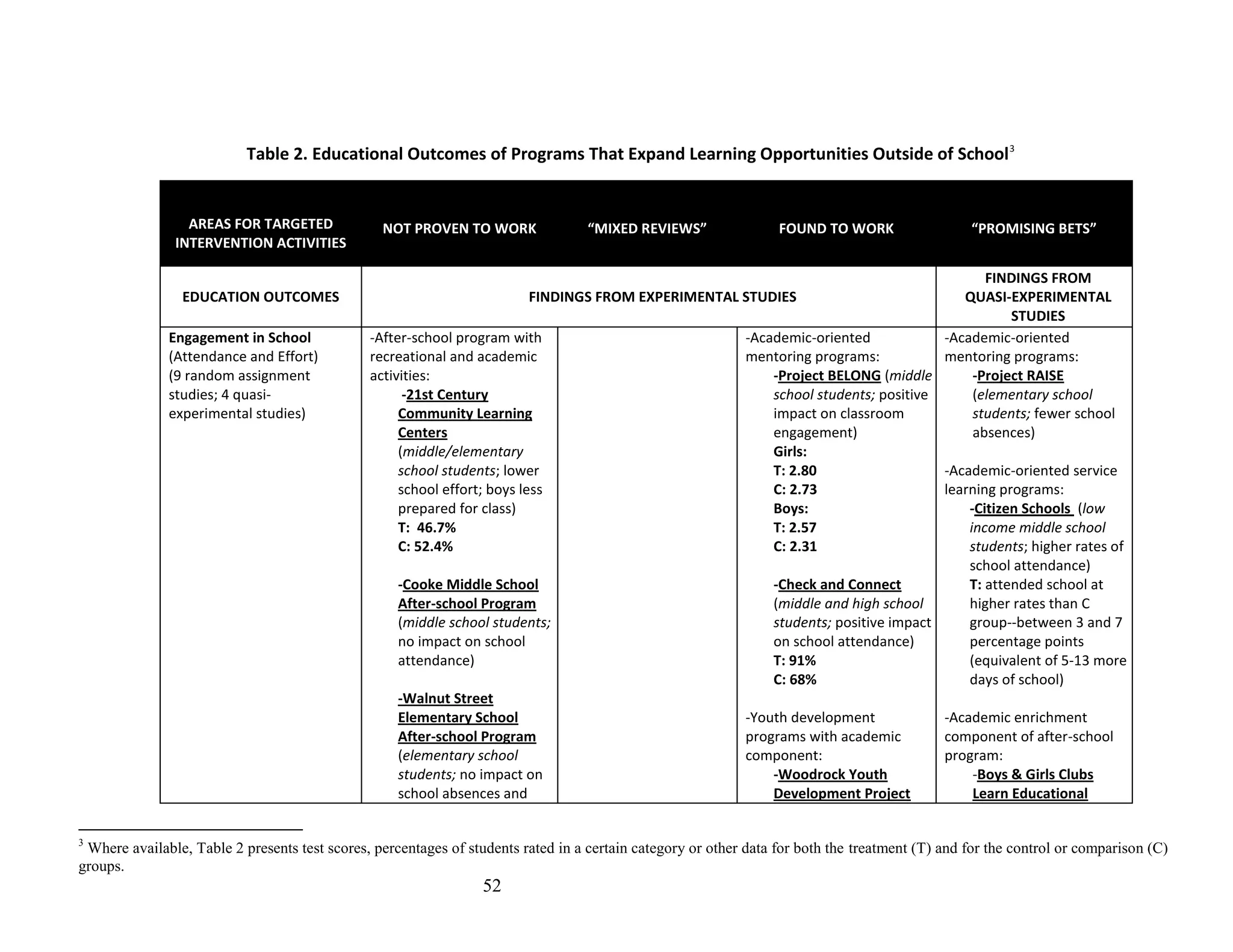

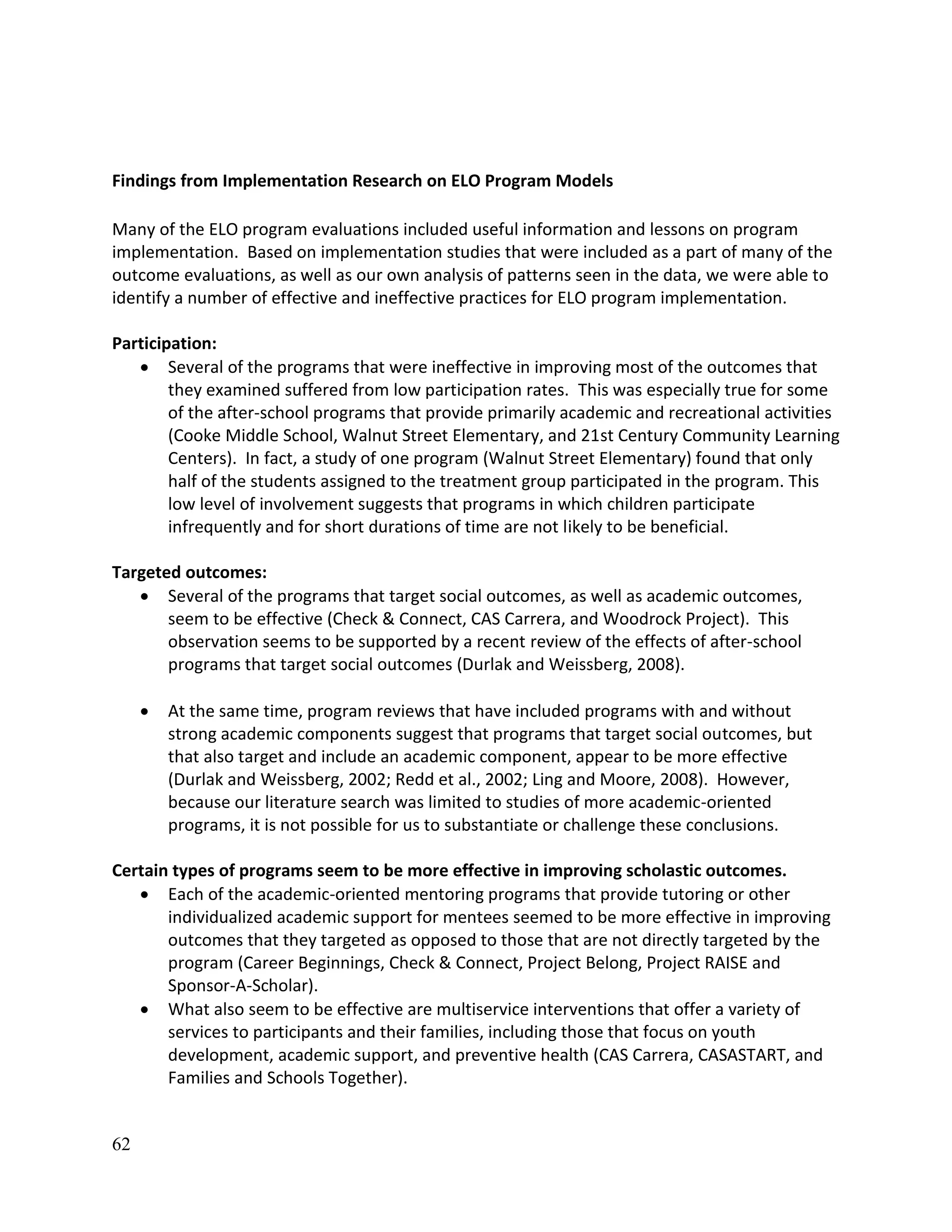

This document provides a review of research on programs that aim to expand learning time for students both inside and outside of the regular school day. It begins with background on the need to improve education in the US. It then describes three types of extended learning time models: extended school day programs that lengthen the school day; extended school year programs that lengthen the school year; and expanded learning opportunity programs that provide academic supports outside of school hours. The report analyzes research on the effectiveness of each type of program at improving student achievement and other educational outcomes. It concludes by discussing implications for funders, policymakers, educators and others.

![49

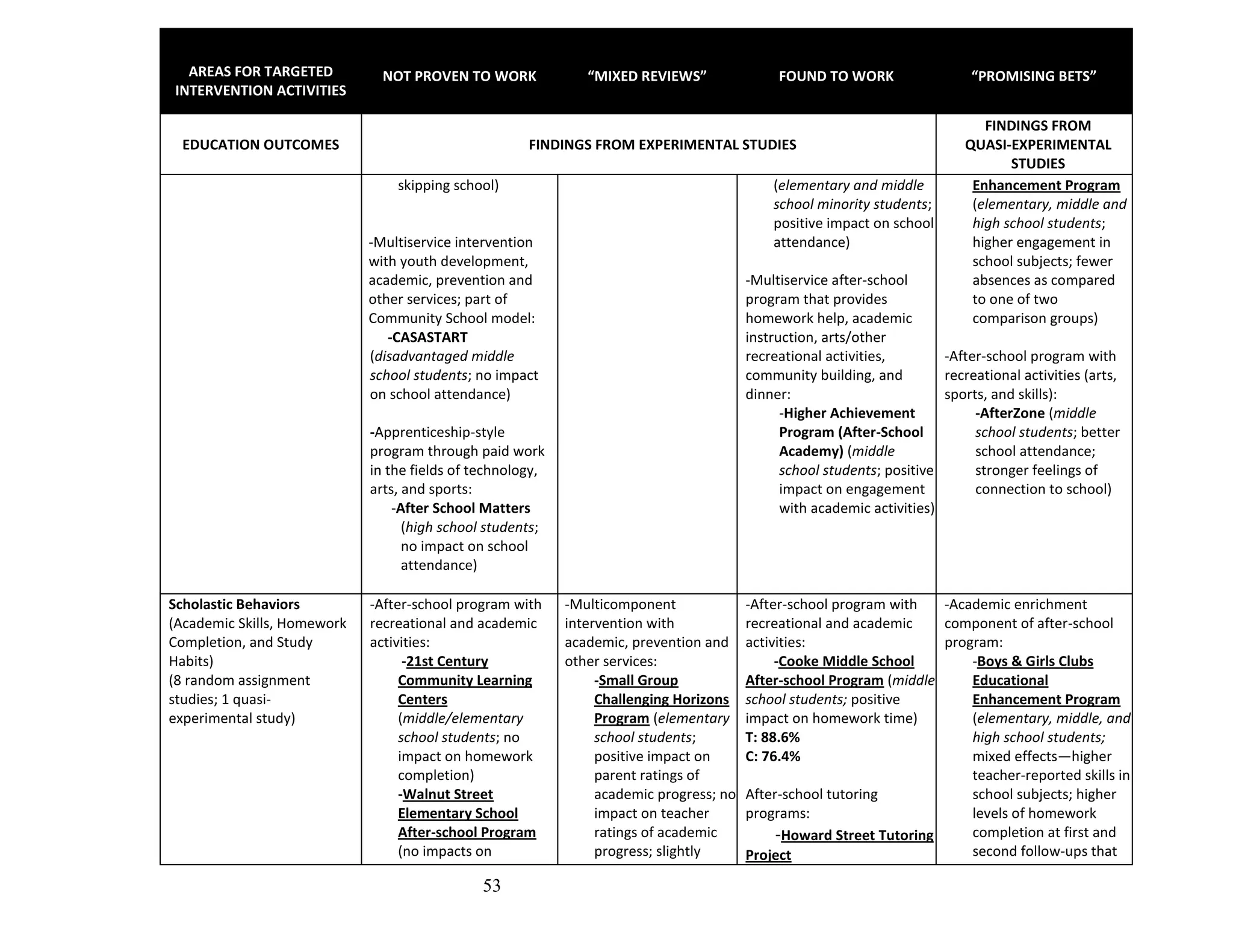

study habits, five programs were found to have a positive impact on outcomes, such as reported

academic skills and school work (Cooke Middle School, CAS Carrera, Howard Street Tutoring, Project

Belong, and Quantum Opportunities). Studies of three programs—including two after-school programs

and one youth development program (21st CCLC, Quantum Opportunities, and Walnut Street

Elementary)—found that the programs were not effective in improving homework outcomes. One

program (Small Group Challenging Horizons) was found to have outcomes that varied by raters, with

parents reporting more favorable outcomes than did teachers

A quasi-experimental study of an academic-oriented after-school program (Boys & Girls Clubs-

Educational Enhancement) found higher levels of homework completion at the first two follow-ups

that had faded out by the time of the final follow-up.

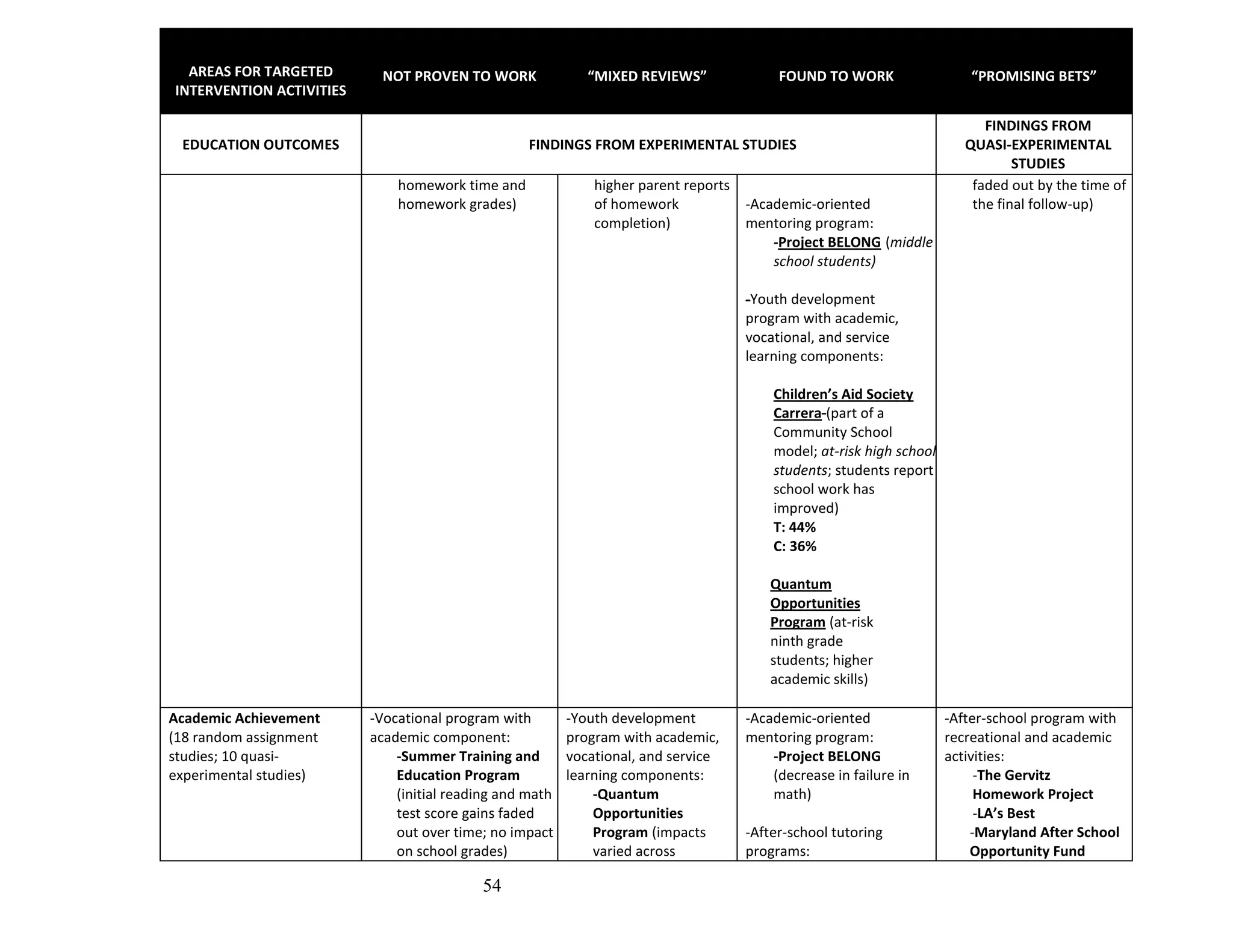

Academic Achievement:

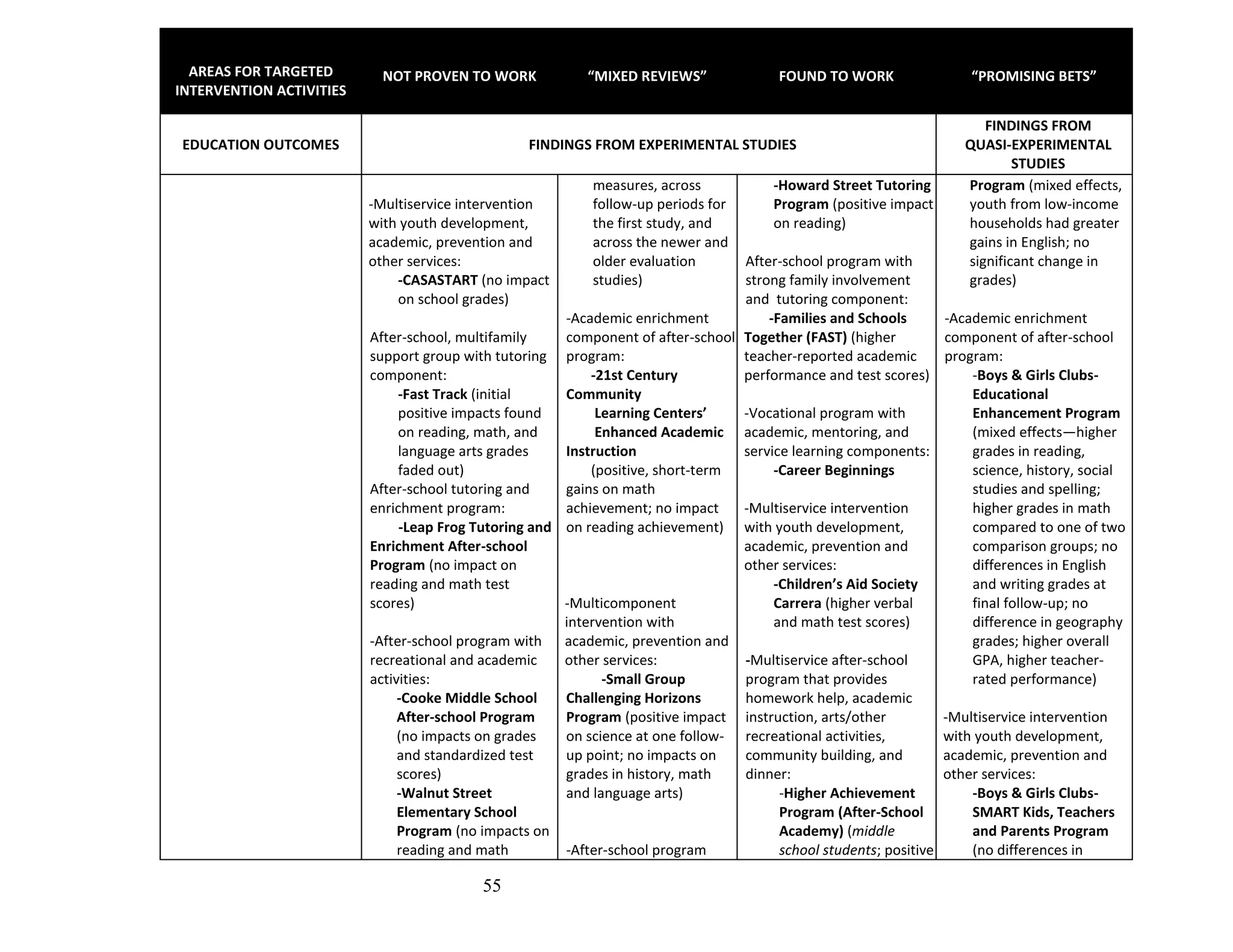

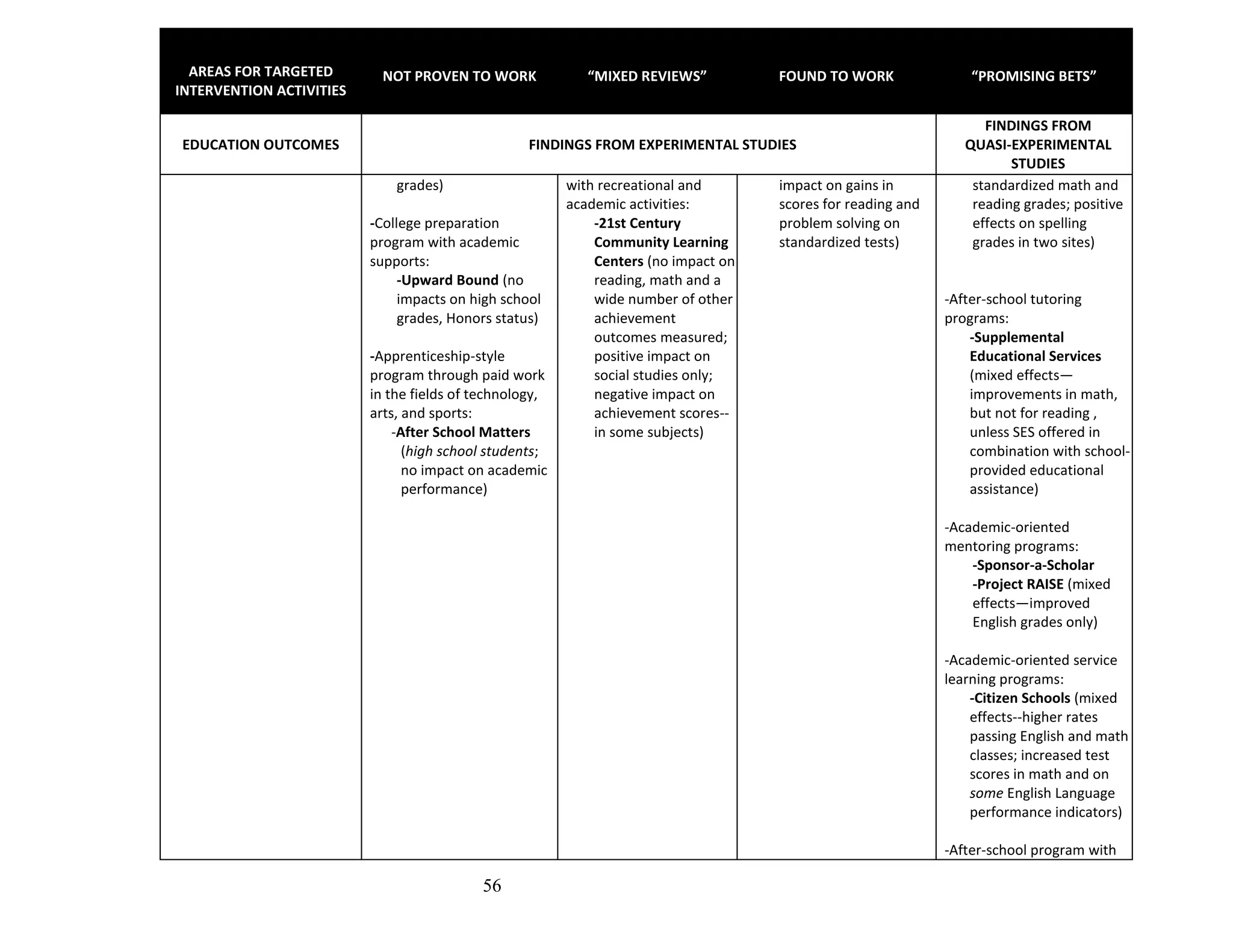

While some ELO programs were able to improve academic achievement, programs were not

consistently effective in producing positive and lasting improvements on this outcome. Of the 18

experimentally evaluated programs that sought to improve students’ academic achievement, one-third

was found to produce mostly positive impacts (Project Belong, Howard Street Tutoring, Families and

Schools Together, Career Beginnings, CAS Carrera, and Higher Achievement). These programs targeted

students at different grade levels. Another four programs had mixed effects on academic achievement

outcomes, mostly due to programs having positive impacts on a few measures of achievement, but not

on others (21st CCLC, 21st CCLC-Enhanced Academic Instruction, Small Group Challenging Horizons,

and Quantum Opportunities). The remaining eight experimentally evaluated programs had no impacts

on academic achievement outcomes (After School Matters, CASASTART, Upward Bound, Summer

Training and Education Program [STEP], Fast Track, Leap Frog, Cooke, and Walnut Street Elementary).

Findings about an additional 10 programs that were evaluated using quasi-experimental designs

showed that the programs had mixed or limited effects on academic achievement, with positive

findings found for some measures, but not others (AfterZones, Gervitz Homework, LA’s BEST, Citizen

Schools, Sponsor a Scholar, Maryland Afterschool, Boys & Girls Clubs-Educational Enhancement, Boys

& Girls Clubs-SMART Kids, Supplemental Educational Services, Project RAISE). No consistent patterns

were found in favor of one subject over another or in favor of test scores over grades or other

achievement measures; however it seems that ELO studies were more likely to examine grades than

they were to examine test scores.

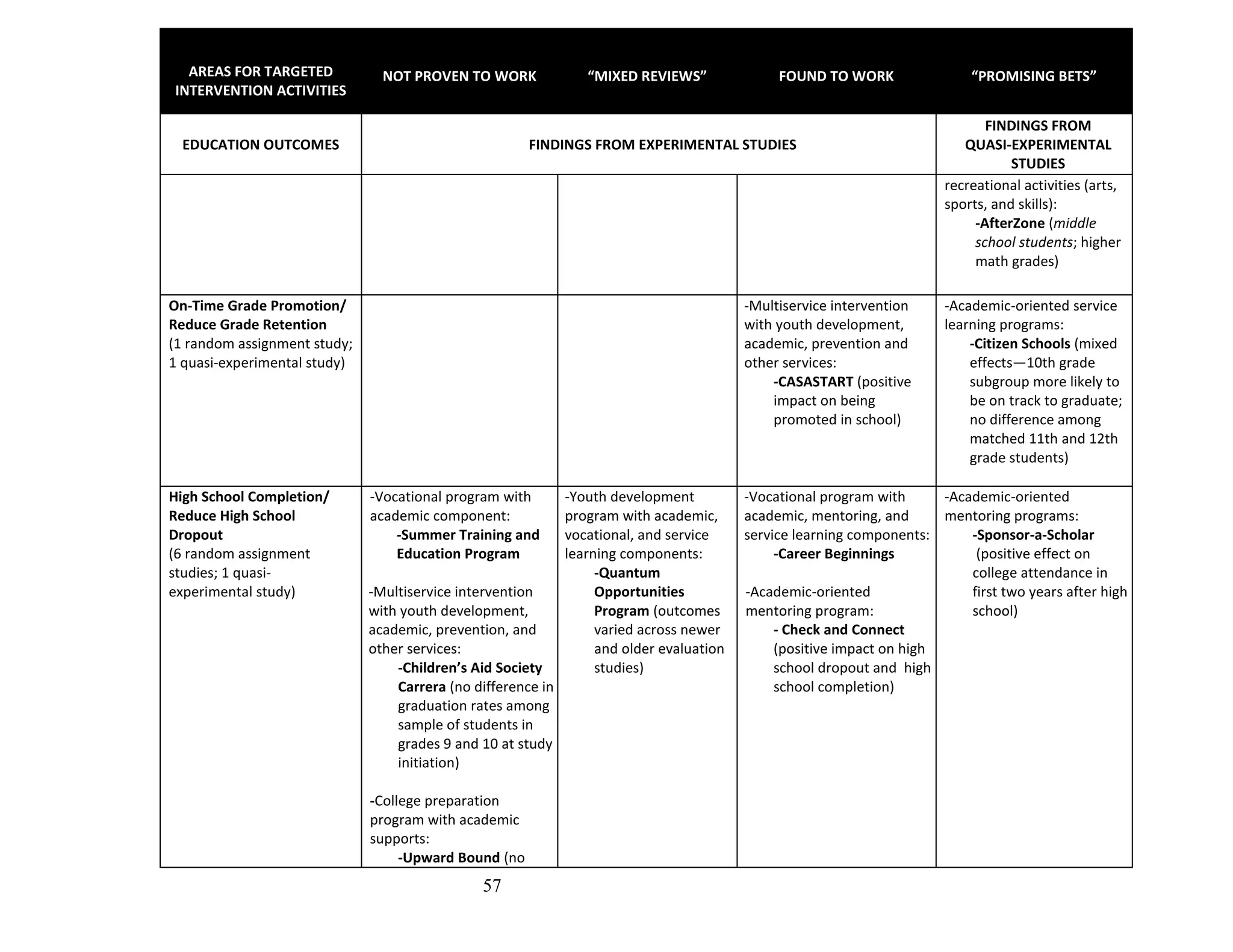

On-Time Grade Promotion

Involvement in expanded learning programs seemed to have a positive effect on another measure of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/expanding-timefor-learning-both-inside-and-outside-the-classroom-210505023926/75/Expanding-time-for-learning-both-inside-and-outside-the-classroom-49-2048.jpg)