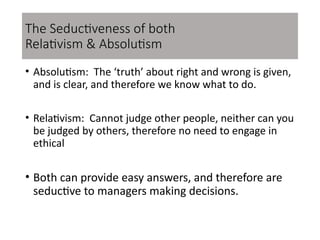

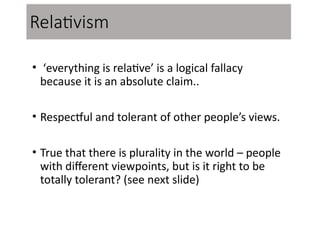

The document “Ethics Lecture 8-2” is a structured academic presentation that explores major philosophical approaches to ethics, focusing particularly on the tensions between absolutism, relativism, Aristotelian justice, and pragmatic ethics. It begins by introducing the concepts of absolutism—the view that truth about right and wrong is clear, fixed, and universally applicable—and relativism, which argues that moral judgments are culturally bound, making cross-judgment illegitimate. The lecture warns that while both positions offer seductive simplicity for decision-makers, they undermine meaningful ethical deliberation. Absolutism risks intolerance in pluralistic societies, whereas relativism discourages the development of new norms in response to global and technological change. Through references to Simon Blackburn’s Being Good (2001), the lecture critiques cultural relativism, emphasizing that tolerance has limits when faced with harmful practices such as slavery or female genital mutilation.

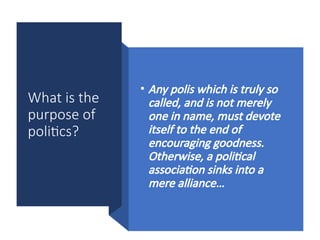

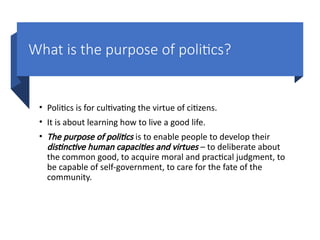

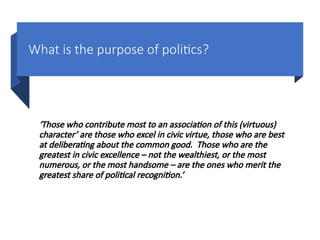

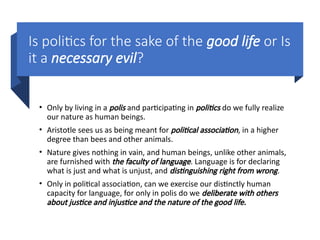

From there, the presentation transitions to Aristotle’s theory of justice, stressing its teleological (purpose-driven) and honorific nature, meaning justice involves both identifying the purpose of social practices and recognizing the virtues that deserve reward. Aristotle’s reflections on politics follow, where politics is portrayed not as a necessary evil but as the highest human association, designed to cultivate civic virtue, moral judgment, and deliberation about the common good. Politics, in this view, is the arena in which humans fulfill their distinct capacity for language and ethical reasoning, moving beyond private life into shared responsibility for community welfare.

The document then highlights Aristotle’s “learning by doing” principle, where moral virtue is cultivated through practice and habit. Laws play a formative role by instilling good habits in citizens, while civic life develops their capacity for deliberation. Ethical character is not innate but constructed through consistent practice, demonstrating Aristotle’s belief that habituation precedes genuine virtue.

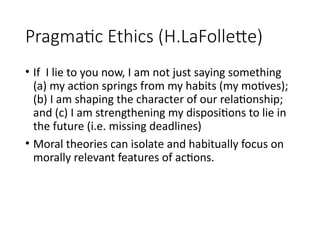

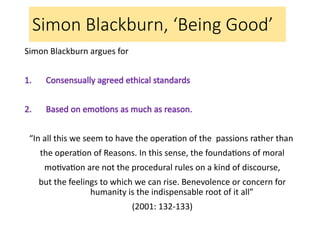

The final part of the lecture turns toward pragmatic ethics, drawing on thinkers like John Dewey, Richard Rorty, Amartya Sen, Simon Blackburn, and historically David Hume. Pragmatism challenges purely rationalist ethics by grounding moral evaluation in practice, habit, and lived experience. Charles Peirce’s distinction between theory and practice is introduced, portraying deliberation as imaginative preparation for action. Morality here is understood as habitual but guided by ideals, social influence, and reflective self-assessment. LaFollette’s insights on habits as “two-edged swords” illustrate how dispositions shape not only actions but also future character. Pragmatic ethics emphasizes that moral agency entails responsibility: individuals and societies can reshape habits to align with ethical ideals, and genuine goodness requires consistent, embodied action rather than ab

![Most people would not

approve of:

‘slave-owning societies and caste

societies, societies that tolerate

widow-burning, or enforce female

genital mutilation, or [that]

systematically deny education and

other rights to women’ (2001: 23)

‘… there is the strong feeling most of us have

that these things just should not happen, and we

should not stand idly by while they do’ (2001: 24)

(Simon Blackburn (2001) Being Good)

Cultural Relativism

Blackburn (2001) also published in this form:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ethicslecture8-2-250904035319-0791aff8/85/Ethics-Lecture-Power-point-lecture-notes-4-320.jpg)