The document describes an environmental sustainability matrix created by IGD's Industry Sustainability Group to help food and grocery companies better understand sustainability issues across their supply chains. The matrix breaks down four key environmental topics - greenhouse gases, water, packaging, and waste - across each stage of the supply chain from raw materials to end of life. It provides definitions, issues, solutions, and links to further resources for each intersection. The goal is to improve understanding of sustainability challenges and opportunities among non-sustainability practitioners in the industry. Users can navigate the interactive PDF matrix to learn about specific topics and stages of the supply chain.

![BACK TO MATRIX To suggest amends/updates to content, email: Toby.Pickard@igd.com

Please give us feedback

Example of the percentage of embedded GHG

emissions within different products

The table below shows the percentage of GHG emissions

produced by products at different stages of the supply chain. The

benefit of product analysis to this level is that ‘hot spots’ can be

identified. For example, the majority of the GHGs that are

embedded in a detergent occur in the ‘use by’ phase in the form

of energy used to heat the water, drive the washing machine etc.

Improved knowledge has resulted in the reformulation of some

detergents to enable consumers to wash at a lower temperature.

In contrast, the hot spot for milk is at the raw material (farm)

stage. The GHGs come from a variety of sources including

fertilisers applied to grassland, fossil fuels, energy in milking

parlours and methane emitted by dairy cattle.

Greenhouse gases

Raw material

production

Manufacture/

processing

Logistics/

distribution

Retail Use by

consumer

Recycling and

disposal

Detergent 21% 2% 2% 0.5% 67.5% 7%

Orange juice 28% 19% 47% 5% 1% 0%

Potato crisps 36% 51% 10% 0% 3%

Bread 45% 23% 4% 2% 23% 3%

Milk 73% 9% 3% 10% 3% 2%

back to matrix

page 2 of 2

Example of the percentage of embedded GHG emissions within different products

Source: The University of Manchester, Sustainable Consumption Institute, Report Consumers, business and climate change, 2009 [opens PDF, page 28]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21e034b0-2dcd-4b88-9663-4ebb36354e65-150715143437-lva1-app6891/85/Environmental_Sustainability_Matrix-4-6-320.jpg)

![BACK TO MATRIX To suggest amends/updates to content, email: Toby.Pickard@igd.com

Please give us feedback

Description of greenhouse gases from raw

materials

The greenhouse gases (GHGs) arising from raw materials in the

food and grocery supply chains are predominately from nitrous

oxide (from crops and livestock production), methane (from

livestock production and biodegradable waste) and carbon

dioxide (from energy use and land management).

What are the common issues with GHGs within the

supply chain?

Continued emissions of GHGs will further exacerbate the impact

of climate change, which presents businesses with additional

risks. There are national and international targets to reduce

GHGs. GHG emissions are a cost to business due to taxation,

less efficient energy use and rising costs.

To find out more about GHGs click here.

What are the key issues with GHGs and raw

materials?

GHG emissions associated with food raw materials come mainly

from the agricultural phase. Not all these emissions will be

created in the country in which the product is manufactured and

ultimately used/consumed. Supply chains are increasingly

global, and raw materials will be sourced from different

geographies reflecting availability, seasonality and cost.

Manufacturers therefore need to recognise their responsibilities

to work with suppliers of raw materials from all geographies to

reduce their GHG emissions.

Direct emissions from farming and changes in land use account

for about 7% of UK greenhouse gas emissions (Source: HM

Government). The Climate Change Act 2008 requires a reduction

in greenhouse gas emissions across the economy by at least

80% below 1990 levels by 2050, and agriculture will need to

play its part in achieving this.

The nature of raw material GHG

emissions is very different from

other sectors of the economy such

as electricity generation, transport,

manufacturing, etc. The principal

GHG for most industries is carbon

dioxide from fossil fuel combustion,

while for agricultural systems

methane and nitrous oxide are the

main GHGs. These arise from

natural, biological processes that

are difficult to manage and subject to seasonal and annual

variability as a function of the weather, crop yield, and natural

processes in the case of methane from dairy cows.

For more in-depth information about global food and farming

meeting the challenges of a low emissions world click here.

Can GHGs be measured?

• The energy (fuel, electricity etc.) required to produce raw

materials for supply chains can be measured and this can be

converted into a GHG emission equivalent

• Determining emissions of methane and nitrous oxide is much

more complex and currently only coarse estimations of

emissions are possible, which are subject to considerable

uncertainty

What can be done to reduce the impact and what

are the opportunities?

Evidence suggests that by improving on-farm efficiency, farmers

can both save money and reduce emissions.

The UK agriculture industry’s GHG Action Plan [opens PDF] aims

to help farmers improve their use of energy and nutrients, their

management of crops and livestock and reduce emissions

without compromising domestic production.

This could be achieved by:

• Use of on-farm anaerobic digestion (AD)

• Use of bio-fuels in agricultural vehicles

• Increased energy efficiency

• Increased feed efficiency

Identifying the risks, challenges and potential

pitfalls

There is a risk that driving down emissions from agriculture in

the UK will compromise production, which could result in

‘exporting’ the UK’s production and emissions to other parts of

the world.

Greenhouse gases and raw materials

continues

page 1 of 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21e034b0-2dcd-4b88-9663-4ebb36354e65-150715143437-lva1-app6891/85/Environmental_Sustainability_Matrix-4-7-320.jpg)

![BACK TO MATRIX To suggest amends/updates to content, email: Toby.Pickard@igd.com

Please give us feedback

Equally, just because food has been imported it does not

necessarily mean it will have more GHG emissions associated

with it compared to food grown in the UK. Food grown in a more

suitable climate may have lower emissions, even when including

transportation, than food grown locally. Examples of can be view

here.

However, whatever the country of origin of food there is a need to

improve agricultural GHG inventory that accurately reflects

progressive changes in farming practice, such as improvements

to livestock diets, nutrient management and manure

management.

A key challenge is establishing realistic goals for reducing

agricultural GHG emissions towards a minimum future level,

beyond which it may not be biologically possible to make further

reductions.

Industry needs to remain open to future technological

breakthroughs or innovative production systems that might be

possible in the long term.

There is a need to be mindful of potential conflicts with other

sustainability related issues, such as intensification to reduce

overall emissions versus animal welfare (i.e. lower GHG systems

are often the most intensive; which means that there may be a

trade off between lowering GHGs and animal welfare).

Where to go for more information

• Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs

• Greenhouse Gas Action Plan [opens PDF]

• Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (AHDB) e.g.

EBLEX’s work for the beef and sheep sectors

• Department for Energy and Climate Change

• The Milk Roadmap: One year down the Road [opens PDF]

• IGD’s Greenhouse Gas Management Report Library on igd.

com

Relationship of GHG emissions from raw materials

to other points in the supply chain

GHG emissions arising from raw materials in the food and

grocery supply chains are predominately from methane, nitrous

oxide and carbon dioxide and can contribute a significant

amount of GHG emissions compared to other areas of the supply

chain.

Case studies

• Müller - Sustainable Dairy Goodness

• Produce World Group - Managing non-financial information to

drive sustainability

• Sainsbury’s - first Carbon Trust certified carbon measure for

dairy farmers

Greenhouse gases and raw materials

back to matrix

page 2 of 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21e034b0-2dcd-4b88-9663-4ebb36354e65-150715143437-lva1-app6891/85/Environmental_Sustainability_Matrix-4-8-320.jpg)

![BACK TO MATRIX To suggest amends/updates to content, email: Toby.Pickard@igd.com

Please give us feedback

What can be done to reduce the impact and what

are the opportunities?

There are a number of initiatives that can be implemented to

reduce the impact of GHG emissions directly associated with

manufacturing, such as:

• Improving energy efficiency

• Switching to lower carbon fuels

(e.g. coal or oil to natural gas) or on-site generation

(e.g. Combined Heat and Power)

• Using renewable energy sources

• Changing refrigerant gas types and minimising leakage

Energy efficiency opportunities will vary across individual sites

and processes. The potential areas for greatest improvement are

typically linked to the areas of greatest energy use, for example

cooking and refrigeration.

There are a number of options available for renewable energy

(for example through renewable tariffs, direct purchase and

installation of renewables on manufacturing sites, or third party

installation and operation on a host site). The business case for

some renewables has been improved through the introduction of

incentives such as the Feed-In Tariff and the Renewable Heat

Incentive.

The financial benefits of improving energy efficiency to reduce

GHGs make it an attractive area for companies to address.

Commercial buildings are responsible for approximately 17% of

UK energy use, but despite this, the Carbon Trust estimates that

businesses in the UK waste some 10-20% of the energy they buy

due to poor control of heating, air conditioning and ventilation

and through leaving lights and appliances on when not in use.

The Carbon Trust report The Business of Energy Efficiency is

available to download here

Identifying the risks, challenges and potential

pitfalls

Many of the new renewable options do not meet the relatively

short-term payback criteria for investment required by companies

(often two years). In order to progress in some of these

technologies there may be a requirement to go into relatively

long term third party finance/design/building/operating type

agreements, which could be from 5-25 years depending on the

type and scale of installation. This would bring inherent risks and

potential liabilities for commercial and private sector investors.

The projected uplift in biomass boilers and Combined Heat and

Power (CHP) plants carries a risk associated with securing a long

term supply of fuel, and the price of this in the medium to long

term as demand rises.

Energy prices are notoriously volatile, making longer investment

decisions in utilities infrastructure a difficult process. Current

uncertainty over future Climate Change Agreements and carbon

prices within the scheme add to this uncertainty.

Some organisations offset GHG emissions through specific

schemes. However, there is a need to check the validity of such

schemes. The Department of Energy and Climate Change does

recognise a number of organisations that offer such services,

however, best practice is to reduce the GHG emissions on site as

much as possible, rather than relying on offsets. Click here to

see The UK Government’s Quality Assurance Scheme for Carbon

Offsetting.

Where to go for more information

• Department of Energy & Climate Change

• Final submission of the Food Industry Sustainability Strategy

Champions’ Group on Energy and Climate Change [opens

PDF]

• The Carbon Trust

• The Environment Agency (Carbon Reduction Commitment)

• Renewable Energy Association

• Defra: F-gas Support (Refrigerants )

• IGD’s Greenhouse Gas Management Report Library on igd.

com

Relationship of GHG emissions from manufacturing

to other points in the supply chain

The GHG emissions from manufacturing will vary considerably

depending on the product or service.

Products that require more processing or refrigeration are likely

to have a higher GHG impact.

Case studies

• Alpro UK Ltd. - CO2 Neutrality

• Heinz - Cuts energy and carbon

• Kraft Foods - Energy and carbon savings

• United Biscuits - Reducing Carbon Emissions

Greenhouse gases and manufacturing

back to matrix

page 2 of 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21e034b0-2dcd-4b88-9663-4ebb36354e65-150715143437-lva1-app6891/85/Environmental_Sustainability_Matrix-4-10-320.jpg)

![BACK TO MATRIX To suggest amends/updates to content, email: Toby.Pickard@igd.com

Please give us feedback

Description of greenhouse gases from transport

Transport takes place between all points of the supply chain.

However the main focus in this cell is heavy goods vehicle used

to transport raw materials and finished goods to point of

purchase. For the purpose of this cell, we refer to the movement

of resources, not people.

Transport covers different modes (road, water, air and rail) all of

which are relevant to the food and grocery industry.

What are the common issues with GHG within the

supply chain?

Continued emissions of greenhouse gas (GHG) will further

exacerbate the impact of climate change, which presents

businesses with additional risks. There are national and

international targets to reduce GHGs. GHG emissions are a cost

to business due to taxation, less efficient energy use and rising

costs.

To find out more about GHGs click here.

What are the key issues with GHGs and transport?

The food and grocery industry is accountable for approximately

25% of all HGV vehicle kilometers in the UK (Defra).

The transport of resources requires energy. This energy will be

provided in a number of different forms: liquid fuels, gaseous

fuels and electricity for example. Each fuel type has a different

GHG emissions factor. Vehicle design, size and weight, engine

size, fuel type, and driver style all play a role in the emissions

created. External factors, particularly congestion, can also be

significant factors.

Can GHGs be measured?

It is possible to measure the GHG emissions of transport by

knowing the type of fuel, the consumption rate of the mode of

travel and the distance travelled.

To see conversion factors click on the following link: July 2011

Guidelines to Defra/DECC’s Greenhouse Gas Conversion Factors

for Company Reporting [opens Excel 1.3 MB]

What can be done to reduce the impact and what

are the opportunities?

There are a number of strategies to reduce GHG emissions from

transport, these include:

• Reducing the absolute amount of transport required – better

loading patterns, route planning, redesigning products and

packaging to enhance the load factor

• Using alternative fuels, such as LPG and electric. Some

companies have started to use rail, waterways and double

deck trailers to reduce GHG associated with transportation

• Using waste product as a fuel, such as waste cooking oil

and/or second generation biofuels

• Reducing ‘empty running’

• Making best use of new technologies to improve vehicle

aerodynamics, route planning and load capacity

• Train drivers to reduce consumption through better driving

• Collaborating with other transport users and operators to

share transport

Identifying the risks, challenges and potential

pitfalls

Some lower GHG fuels may have worse air quality emissions

than the fuels they are replacing, though these can be mitigated

by new technologies.

Biofuels have been linked to increasing costs of some food

stuffs, causing ethical concerns around using food for fuel.

However, second generation biofuels could help alleviate this

challenge.

Electric vehicles do not create any emissions themselves (known

as ‘direct emissions’). However, depending on the source of

electricity used to charge them, there may be emissions

associated with this electricity from conventional power sources.

Recognising the difference between test conditions and ‘real

world’ running conditions and understanding why variations may

occur when purchasing vehicles.

Understanding the vehicle mix - goods are moved by a

combination of vans, fixed load trucks and articulated vehicles

Greenhouse gases and transport

continues

page 1 of 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21e034b0-2dcd-4b88-9663-4ebb36354e65-150715143437-lva1-app6891/85/Environmental_Sustainability_Matrix-4-13-320.jpg)

![BACK TO MATRIX To suggest amends/updates to content, email: Toby.Pickard@igd.com

Please give us feedback

Where to go for more information

• The Guidance on measuring and reporting Greenhouse Gas

emissions from freight transport operations [PDF 3.7 MB –

Please note this is a large file. You may find it easier to save

this file to your computer before opening it]

• Quick reference guide for transport operators

• Toolkit for freight transport operators to calculate their Scope

3 emissions [opens Excel 1.3 MB]

• Optimising Load Fill: A Best Practice Guide

• Optimising Transport Modes

• Transport Technology User Guide & Assessment Tool

• Consolidated Distribution

• IGD’s Greenhouse Gas Management Report Library on igd.

com

Relationship of GHG emissions from transport to

other points in the supply chain

Depending on the type of transportation mode used and the

requirements of the products being transported the GHG

emissions will vary considerably.

If the product requires chilling during transportation its GHG

emissions will be higher.

Case studies

• ASDA - Being sustainable in a recessionary environment

• Asda ‘Fewer, Friendlier Miles’

• Warburtons - Reducing carbon by reducing road miles

• HEART of ENGLAND fine foods - reducing road miles through

supply chain collaboration

• Mars and Nestlé

• Nestlé and United Biscuits – Taking a unique approach to

collaboration

• Sainsbury’s – Food deliveries made by lorry running on

rubbish

• Convert2Green and 3663 - Turning waste into fuel

Greenhouse gases and transport

back to matrix

page 2 of 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21e034b0-2dcd-4b88-9663-4ebb36354e65-150715143437-lva1-app6891/85/Environmental_Sustainability_Matrix-4-14-320.jpg)

![BACK TO MATRIX To suggest amends/updates to content, email: Toby.Pickard@igd.com

Please give us feedback

Description of greenhouse gases from wholesale

and retail

The greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions associated with wholesale

and retail premises depends on a number of factors. These

include: energy source used on site, energy consumption, hot or

cold water consumption, static diesel fuel on site, the type of

refrigerants used.

There are other factors that depend on location and proximity to

depots and customers, which are not considered in this cell.

What are the common issues with GHGs within the

supply chain?

Continued emissions of GHGs will further exacerbate the impact

of climate change, which presents businesses with additional

risks. There are national and international targets to reduce

GHGs. GHG emissions are a cost to business due to taxation,

less efficient energy use and rising costs.

To find out more about GHGs click here.

What are the key issues with GHGs and wholesale

and retail?

Commercial buildings are responsible for approximately 17% of

UK energy use, but despite this, the Carbon Trust estimates that

businesses in the UK waste some 10-20% of the energy they buy

due to poor control of heating, air conditioning and ventilation

and through leaving lights and appliances on when not in use.

The Carbon Trust report The Business of Energy Efficiency is

available to download here.

Individual wholesale and retail premises vary enormously in their

environmental performance. The age and the degree to which

the property has been modified to improve insulation and

building integrity as well as the upgrading of the key technologies

of air handling, refrigeration and heating are all major factors in

the amount of GHG emissions emitted.

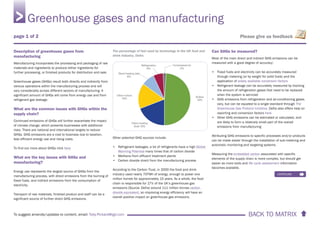

The pie chart gives an indication of the percentage of fuel used

by technology within the food and drink industry.

The percentage of fuel used by technology in the UK food and

drink industry, Defra

The use of hydroflurocarbon refrigerants can contribute

significantly to GHG emissions due to refrigerant gas leakage

and their very high Global Warming Potential. The food and drink

industry is one of the main users of refrigeration. For many

businesses refrigeration costs can account for up to 50% of all

electricity used on site (Source: Carbon Trust).

Can GHGs be measured?

The consumption of electricity, hot or cold water, oil or gas is

generally well metered and this can be converted into GHG

equivalent carbon emission figures. To see conversion factors

click on the following link: July 2011 Guidelines to Defra/DECC’s

Greenhouse Gas Conversion Factors for Company Reporting

[opens Excel 1.3 MB]

The type and loss of refrigerants from air conditioning units and

fridge/freezers can easily be measured through annual

consumption figures as part of strict maintenance procedures.

To see conversion factors click here.

What can be done to reduce the impact and what

are the opportunities?

Lighting costs can be as much as 40% of a building’s electricity

consumption. The correct use of lighting controls to reflect actual

occupation and daylight linking can reduce operating costs by

between 25% and 50% (Source: Energy Services and Technology

Association).

Reductions can also be delivered by:

• Improved monitoring, such as smart electricity monitors

• Better use and control of consumption, i.e. turning

equipment off when not required

• Improved insulation of the building

• Staff training and the development of energy champions to

drive performance

• Heat reclamation and improved air handling technologies

Greenhouse gases and wholesale and retail

continues

page 1 of 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21e034b0-2dcd-4b88-9663-4ebb36354e65-150715143437-lva1-app6891/85/Environmental_Sustainability_Matrix-4-15-320.jpg)

![BACK TO MATRIX To suggest amends/updates to content, email: Toby.Pickard@igd.com

Please give us feedback

• Converting to lower Global Warming Potential GHG

refrigerants and better maintenance to reduce leakage of

refrigerant gases

• The source and type of the energy is critical. Local generation

from renewable resources and the development of

community generation schemes can offer lower emissions

and other benefits

Identifying the risks, challenges and potential

pitfalls

Energy efficiency technologies to mitigate GHG emissions require

investment. Introducing new technologies can mean significant

reductions in GHG emissions, but payback periods may be long

and therefore the technology could be rejected using standard

‘return on investment’ criteria. Changes in legislation and/or

incentives (e.g. Feed-In Tariff and the Renewable Heat Incentive)

can change the economics significantly at short notice and

should be continually monitored.

Some organisations offset GHG emissions through specific

schemes. However, there is a need to check the validity of such

schemes. The Department of Energy and Climate Change does

recognise a number of organisations that offer such services,

however, best practice is to reduce the GHG emissions on site as

much as possible, rather than relying on offsets. Click here to

see The UK Government’s Quality Assurance Scheme for Carbon

Offsetting

Where to go for more information

• Guidance on how to measure and report your greenhouse

gas emissions

• The Carbon Trust

• Small Business User Guide: Guidance on how to measure

and report your greenhouse gas emissions [opens PDF 260

KB]

• RICS: Green Building Information Gateway

• BREEAM: the Environmental Assessment Method for

Buildings Around The World

• Building Research Establishment: Sustainable construction

of buildings

• Carbon Trust: Low Carbon Buildings Accelerators

• Carbon Trust: Low carbon refurbishment of buildings -

Management guide

• Building Regulations

• Business Link: Use resources efficiently in your retail

business

• IGD’s Greenhouse Gas Management Report Library on igd.

com

Relationship of GHG emissions from wholesale and

retail to other points in the supply chain

Overall, the GHG emissions associated with wholesale or retail

stores in relation to the total GHG emissions of a supply chain

will be relatively small.

For specific products the retail element can vary hugely: e.g. 0.5

% for washing powder to 10% for milk. See GHG definition page

for further information, click here

Case studies

• Morrisons – ‘Cut the Carbon Campaign’

• Sainsbury’s – Opens the UK’s greenest stores

• Tesco - Creating a Greener Store

• The Co-operative Food - Green Store CO² Refrigeration

Systems

Greenhouse gases and wholesale and retail

back to matrix

page 2 of 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21e034b0-2dcd-4b88-9663-4ebb36354e65-150715143437-lva1-app6891/85/Environmental_Sustainability_Matrix-4-16-320.jpg)

![BACK TO MATRIX To suggest amends/updates to content, email: Toby.Pickard@igd.com

Please give us feedback

Definition and issues with Water

Water is a vital resource for the food and grocery industry. The

food industry uses an estimated 430 mega litres per day of

public water supply, and directly abstracts around 260 mega

litres of water a day, which equates to 10% of water abstracted

by industry in the UK (Defra 2007 [opens PDF]).

With the UK’s water resources coming under ever increasing

pressure from growing public, commercial and industrial

demand, there is a need for the industry to address the effects

of its water consumption on national water security and scarcity,

the impact on local wildlife habitats and water quality.

Direct water within the food and grocery industry

The illustration, Figure 1, highlights the different direct uses of

water across the major stages of the food and grocery supply

chain. Energy, and its associated water use, is linked to all

activities.

Water scarcity

Water scarcity is already an issue in the UK. Per person, the UK

has less water available than most EU countries. Most of the

south and east of England is already severely water stressed.

Waterwise states that the ‘South East of England has less water

available per person than the Sudan and Syria.’ This lack of

water within the south of England has seen a reduction in the

number of water abstraction licences issued to companies.

The combination of limited availability and high demand for

water, including the expected impacts of climate change, mean

many companies are subject to increasing water-related risks.

This will impact food companies specifically with global

agriculture being the biggest user of freshwater, accounting for

70% of worldwide use. This is unlikely to change as estimates

point to an increased need for irrigation in the future if we are to

feed a growing population.

Water

Figure 1: Examples of water use along the food and grocery supply chain

Source: IGD

continues

page 1 of 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21e034b0-2dcd-4b88-9663-4ebb36354e65-150715143437-lva1-app6891/85/Environmental_Sustainability_Matrix-4-19-320.jpg)

![BACK TO MATRIX To suggest amends/updates to content, email: Toby.Pickard@igd.com

Please give us feedback

Water related risk

Water scarcity poses risks to companies as it means that they

may not have sufficient water, or water of the required quality, to

operate.

The water-related risks that companies face have been

summarised by WWF-UK as follows:

• Physical risks – deterioration in product quality/ safety; raw

material or product shortages

• Financial risks – escalating cost of direct water use,

fluctuating and/or escalating cost of raw materials/products/

services, requiring significant water input

• Regulatory risks – tightening regulation leading to cost

increases; outright bans on specific practices and

reputational risks associated with litigation

• Reputational risks – from actual or perceived irresponsible

use of water, either directly by companies or in their supply

chains

A report produced by Ceres, UBS and Bloomberg, called MURKY

WATERS? Corporate Reporting on Water Risk: A Benchmarking

Study of 100 Companies, 2010 [opens PDF], concludes that

most companies operating in water-intensive industries are

failing to provide investors with adequate information on the

water-related risks they face and in many cases have little idea

how their supply chains could be affected by water shortages.

The Earth Policy Institute believes that water scarcity is now the

single biggest threat to global food security. The World Bank has

predicted that by 2025 two-thirds of the world’s population will

not have enough drinking water.

Indirect water use

There is also an issue with indirect water use, (more commonly

known as embedded water), this is the amount of water used in

the entire process of producing, retailing and consuming

(cooking for example) a product. It is also referred to as virtual

water, water footprint, embodied water or shadow water.

The concept is very similar to embedded Greenhouse Gases but

not the same. Understanding and assessing the impact of water

is complicated. Unlike greenhouse gases the impact of water use

varies in location and time, and water can be of many different

qualities. In addition explaining the concept of embedded water

versus direct water consumption is complex.

It is estimated that the average Briton uses about 150 litres of

water per day. If the embedded water used in the production of

the goods people consume is taken into account the daily use

per person in the UK may be nearer 3,400 litres (Source:

Waterwise).

Table 1, shows the percentage of embedded water that goes into

a product, at each section of the supply chain. For example, it is

estimated that 170 litres of water is used in producing one pint

of beer, and one 150 gram burger requires 2,400 litres of water.

For more information and examples see IGD’s Embedded Water

in Food Production factsheet.

Table 1: Embedded water breakdown in different products

Source: WWF, Waterwise, Water Footprint Network and P&G

Water

RAW MATERIAL

PRODUCTION

MANUFACTURE/

PROCESSING

RETAIL USE BY

CONSUMER

RECYCLING

AND DISPOSAL

A sugar carbonated drink 97% 3% <1% <1% <1%

Potatoes 93% 7% <1% <1% <1%

A typical laundry product <1% <1% <1% 99% <1%

back to matrix

page 2 of 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21e034b0-2dcd-4b88-9663-4ebb36354e65-150715143437-lva1-app6891/85/Environmental_Sustainability_Matrix-4-20-320.jpg)

![BACK TO MATRIX To suggest amends/updates to content, email: Toby.Pickard@igd.com

Please give us feedback

Table 3: Drinking water requirements for livestock

Sources: Luke (2003); National Research Council (1985; 1987; 1994; 1998;

2000); Pallas (1986); Ranjhan (1998).

Source: FAO

Can water be measured?

Volume, quality and water scarcity can be measured.

Volume: Measuring use rate is relatively straightforward, and can

be done through the use of water meters. Allowances should be

made for evaporation, transpiration and the efficiency of the

irrigation system.

Quality: There are a number of different measures of water quality

– the most common used by industry are Biochemical Oxygen

Demand, Chemical Oxygen Demand and Total Suspended Solids.

The degree of phosphates and nitrogen can also be measured in

discharge water, as these levels will have implications on soil

management. Key to the actual impact of these measures will be

the sensitivity of the local environment where the discharge

takes place.

Scarcity: There are different methods for measuring localised

water scarcity – physical water scarcity, economic water scarcity

or even political water scarcity can all be used to assess the

potential impacts (and there are different methods and

assumptions used to look at each of these). It is important that

consistent methods are applied when comparing regions. For

more information click here.

What can be done to reduce the impact and what

are the opportunities?

• Know where crops/raw materials are sourced from and what

the issues are within this area

• Consider crops/materials that are less water intensive in

their production

• Optimise irrigation, use boom or trickle irrigation

• Irrigate at night, ensuring the necessary safe working

systems are in place

• Level land to ensure even irrigation

• Manage droplet size on irrigation

• Avoid irrigating in windy conditions to best manage spray

patterns

• Develop water storage facilities

• Use drought resistant crop varieties

• Reduce evapotranspiration

• Form local water abstraction groups to collaborate on better

water management

• Manage wash down and cleaning techniques more efficiently

• Pre-soak vegetables prior to cleaning, this reduces water

needed for the final clean

Identifying the risks, challenges and potential

pitfalls

The FISS Champions Group on Water report [opens PDF],

published in May 2007 identifies the following challenges for

industry:

• Lack of data to enable conclusive economic decisions

• Lack of resources, time and budget

• Uncertainty about financial benefits

• Product quality issues

Water and raw materials

Species Physiological condition Average

weight

Air temperature o

C

15 25 35

Water requirements

(kg) (.......litres/animal/day.....)

Cattle African pastoral system-lactating - 2 litres milk/day

Large breed - Dry cows -279 days pregnancy

Large breed - Mid-lactation - 35 litres milk/day

200

680

680

21.8

44.1

102.8

25

73.2

114.8

28.7

102.3

126.8

Goat Lactating - 0.2 litres milk/day 27 7.6 9.6 11.9

Sheep Lactating - 0.4 litres milk/day 36 8.7 12.9 20.1

Camel Mid-lactation - 4.5 litres milk/day 350 31.5 41.8 52.2

Chicken Adult broilers (100 animals)

Laying eggs (100 animals)

17.7

13.2

33.1

25.8

62

50.5

Swine Lactating - daily weight gain of pigs 200g 175 17.2 28.3 46.7

continues

page 2 of 3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21e034b0-2dcd-4b88-9663-4ebb36354e65-150715143437-lva1-app6891/85/Environmental_Sustainability_Matrix-4-22-320.jpg)

![BACK TO MATRIX To suggest amends/updates to content, email: Toby.Pickard@igd.com

Please give us feedback

• Safety and hygiene issues

• Lack of awareness of the technical feasibility of change

• Customers’ perceptions and potential risks associated with

change

• Fear of potential negative public relations associated with the

above

• Managing effluent as well as water into facilities

• Be aware of flood risk

For further information on flooding click here.

Other risks and challenges are as follows:

• Water demand is likely to increase (due to increasing

population and changing diets)

• Climate change is likely to change rainfall patterns

• More intensive rainfall will increase the risk of flooding

• Public and industry understanding of the issues is low

Where to go for more information

• IGD: Guide to Understanding, Assessing and Managing Water

in Grocery Supply Chains

• Good water stewardship: guidance for agricultural suppliers

[opens PDF]

• Environment Agency: Saving water in agriculture and

horticulture

• NFU Water

• WBCSD Global Water Tool

• Water Footprinting Network

• Regional licensing – England and Wales

• EU Water Framework Directive

• Aqueduct - Measuring and mapping water risk

• CEO Water Mandate

• CDP Water Disclosure

• Water Report Library section within igd.com

Relationships of water and raw materials to other

points in the supply chain

Food raw material production often uses a lot of water. It is

important to be mindful however that using large volumes of

water is not necessarily an issue if water availability in the

location is high. In contrast, production of raw materials for use

in some grocery products (e.g. washing detergents) is relatively

low compared to water used in other parts of the supply chain

(e.g. end user).

Case studies

• Heinz - water conservation

Water and raw materials

back to matrix

page 3 of 3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21e034b0-2dcd-4b88-9663-4ebb36354e65-150715143437-lva1-app6891/85/Environmental_Sustainability_Matrix-4-23-320.jpg)

![BACK TO MATRIX To suggest amends/updates to content, email: Toby.Pickard@igd.com

Please give us feedback

Description of water used in manufacturing

Manufacturing incorporates the processing and packaging of raw

materials and ingredients to produce either ingredients for

further processing, or finished products for distribution and sale.

Water is a vital commodity for manufacturing with a variety of

essential uses such as washing, cleaning, hygiene and

sanitisation, heat transfer (heating and cooling), material

conveying and as an ingredient.

What are the common issues with water within the

supply chain?

The two main issues surrounding water are availability and

quality. Only 0.5% of global water is available as freshwater for

human use, with 97% salt water, and 2.5% locked into glaciers &

ice (WCBSD 2009).

With a rapidly growing global population the availability of fresh

water is an increasing problem for many parts of the world.

Nearly half of Europe’s population live in areas defined as ‘water-

stressed’ (EEA, 2010).

For more information on the common issues, click here.

What are the key issues with water and

manufacturing?

The availability of water for manufacturing is likely to become an

increasingly important issue.

The UK food manufacturing sector has an annual turnover of

around £70billion, and water consumption costs the sector

about 0.5% of this turnover. A 20% reduction in water use would

save the sector in excess of £60 million a year (Source: FISS,

2006 [opens PDF]).

Efficient use of water is an essential requirement for any

manufacturing process to be sustainable in the future.

Consideration needs to be given to the treatment of effluent, the

output quality and cost of treatment.

Manufacturing sites may also be subject to flooding, and should

aim to mitigate this issue. For further information on flooding

click here.

Can water be measured?

Direct water consumption can be relatively easily measured

through the use of meters and is typically measured and charged

for in units of cubic metres. A degree of sub-metering on a

manufacturing site enables a more effective monitoring and

targeting regime to be applied to fully assess the efficiency of

processes and the opportunities for improvement.

A large proportion of water used in manufacturing does not go

into the finished product and will go for treatment before

entering drainage systems. If this water is recycled, water use

can be significantly reduced. This has both cost and legal

compliance implications. With many manufacturing materials

being polluting, the environmental impact of untreated effluent

from manufacturing can be significant.

What can be done to reduce the impact and what

are the opportunities?

A useful exercise is to conduct a water mass balance of a

manufacturing site to help identify all areas of consumption and

assess losses through leakage and evaporation which can be

harder to directly measure (see figure 2 below).

There are a number of water conservation measures to make

more efficient use of water in manufacturing processes, such as:

• Sub-metering, monitoring and targeting, water mapping

• Identification and repair of leaks

• Cleaning – Cleaning in Place (CIP) – water recirculation

• Staff training

• Provide plugs for sinks, fit percussion taps, dual and

waterless toilet facilities

• Recycle water used for vehicle washing

• Capture rainwater and store for future use, known as rain

water harvesting

• Use ponds to collect storm water

• Train staff to address water usage

Water and manufacturing

Figure 2: Diagram of a water mass balance

continues

page 1 of 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21e034b0-2dcd-4b88-9663-4ebb36354e65-150715143437-lva1-app6891/85/Environmental_Sustainability_Matrix-4-24-320.jpg)

![BACK TO MATRIX To suggest amends/updates to content, email: Toby.Pickard@igd.com

Please give us feedback

The Federation House Commitment (FHC) aims to reduce water

usage in companies and work towards an overall industry-wide

water reduction target of 20% by the year 2020. Any

manufacturer in the food and drink industry may join.

Identifying the risks, challenges and potential

pitfalls

The FISS Champions Group on Water report [opens PDF],

published in May 2007 identifies the following challenges for

industry:

• Lack of data to enable conclusive economic decisions

• Lack of resources, time and budget

• Uncertainty about financial benefits

• Product quality issues

• Safety and hygiene issues

• Lack of awareness of the technical feasibility of change

• Customers’ perceptions and potential risks associated with

change

• Fear of potential negative public relations associated with the

above

• Managing effluent as well as water into facilities

• Be aware of flood risk

For further information on flooding click here.

A report produced by Ceres, UBS and Bloomberg, called MURKY

WATERS? Corporate Reporting on Water Risk: A Benchmarking

Study of 100 Companies, 2010 [opens PDF], concludes that

most companies operating in water-intensive industries are

failing to provide investors with adequate information on the

water-related risks they face and in many cases have little idea

how their supply chains could be affected by water shortages.

Where to go for more information

• IGD: Guide to Understanding, Assessing and Managing Water

in Grocery Supply Chains

• Federation House Commitment

• WRAP: Water guides

• WRAP: Rippleffect

• Environmental permitting for discharges to surface water and

groundwater

• EA: Food and drink manufacturing industry environmental

management toolkit [opens PDF]

• EA: Water abstraction

• Regional licensing – England and Wales

• EU Water Framework Directive

• Aqueduct - Measuring and mapping water risk

• CEO Water Mandate

• CDP Water Disclosure

• Water Report Library section within igd.com

Relationships of water in manufacturing to other

points in the supply chain

Manufacturing relies on clean water to make quality products. In

general, manufacturers are in control of water once it enters the

factory. Projects can be carried out to reduce water consumption

by introducing a rigorous approach to water reduction.

Manufacturing companies need to appreciate the volume of

embedded water in their products, and where this embedded

water occurs, for example with food the highest volume of water

use is likely to be in the raw materials used, in laundry products

it is likely to be in the use phase, i.e. washing. For further

information click here.

Case studies

• Greenvale AP - Reducing water and energy use

• Kraft Foods - Water savings

• Warburtons - Measuring, managing and reducing water

usage

Water and manufacturing

back to matrix

page 2 of 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21e034b0-2dcd-4b88-9663-4ebb36354e65-150715143437-lva1-app6891/85/Environmental_Sustainability_Matrix-4-25-320.jpg)

![BACK TO MATRIX To suggest amends/updates to content, email: Toby.Pickard@igd.com

Please give us feedback

Description of water used in storage

Storage can be defined as the placing of goods in a suitable facility,

with the intention of being retrieved at a later date. Storage will take

place for a number of reasons: consolidation, change of mode of

transport, product preservation, strategic and display prior to sale.

This cell looks at the use of water directly associated with storage

operations. This will include water used for cleaning (equipment,

clothes and personal), potentially catering and washing of buildings

and vehicles (based at sites) and toilets.

What are the common issues with water within the

supply chain?

The two main issues surrounding water are availability and quality.

Only 0.5% of global water is available as freshwater for human use,

with 97% salt water, and 2.5% locked into glaciers & ice (WCBSD

2009).

With a rapidly growing global population the availability of fresh water

is an increasing problem for many parts of the world. Nearly half of

Europe’s population live in areas defined as ‘water-stressed’ (EEA,

2010).

For more information on the common issues, click here.

What are the key issues with water and storage?

Storage sites are unlikely to be significant users of water in relation

to other points in the supply chain. However, there may be a

significantly higher impact in areas of, or at times of year of, water

shortage. Storage sites may also be subject to flooding, which can

have a significant impact on operations. Water leaks can lead to

significant increases in consumption, which are not obvious without

metering sites.

Can water be measured?

Water use can be measured at store facilities through water

metering. This, if applied over a significantly short time period, can

identify leaks as they occur. Awareness should also be raised of the

local impact of water consumption.

Facilities should also consider the impact their effluent (waste water)

may have on systems and networks. Effluent treatment is likely to be

a significant cost.

What can be done to reduce the impact and what are

the opportunities?

There are a number of strategies to reduce the impact of water at

storage facilities, which are listed below:

• Provide plugs for sinks, fit percussion taps, dual and waterless

toilet facilities

• Recycle water used for vehicle washing

• Capture rainwater and store for future use, known as rain water

harvesting

• Use ponds to collect storm water

• Train staff to address water usage

Identifying the risks, challenges and potential pitfalls

The FISS Champions Group on Water report [opens PDF], published

in May 2007 identifies the following challenges for industry:

• Lack of data to enable conclusive economic decisions

• Lack of resources, time and budget

• Uncertainty about financial benefits

• Product quality issues

• Safety and hygiene issues

• Lack of awareness of the technical feasibility of change

• Managing effluent as well as water into facilities

• Be aware of flood risk

For further information on flooding click here.

Where to go for more information

• IGD: Guide to Understanding, Assessing and Managing Water in

Grocery Supply Chains

• WRAP: Water guides

• WRAP: Rippleffect

• Environmental permitting for discharges to surface water and

groundwater

• EA: Food and drink manufacturing industry environmental

management toolkit [opens PDF]

• EA: Water abstraction

• Regional licensing – England and Wales

• EU Water Framework Directive

• Aqueduct - Measuring and mapping water risk

• CEO Water Mandate

• CDP Water Disclosure

• Water Report Library section within igd.com

Relationships of water in storage to other points in

the supply chain

The impact of water use in the storage section of the supply

chain will be relatively low compared to other areas of the chain.

However, this doesn’t mean that attempts to reduce water usage

should not be implemented, as significant savings can be made

from relatively easy to implement initiatives, such as rainwater

harvesting, staff training and by using more water efficient

machinery.

Water and storage

back to matrix

page 1 of 1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21e034b0-2dcd-4b88-9663-4ebb36354e65-150715143437-lva1-app6891/85/Environmental_Sustainability_Matrix-4-26-320.jpg)

![BACK TO MATRIX To suggest amends/updates to content, email: Toby.Pickard@igd.com

Please give us feedback

Description of water use in transport

Transport takes place between all points of the supply chain. For

the purposes of this section we refer to the movement of

resources, not people. Transport covers different modes (road,

water, air and rail) all of which are relevant to the grocery sector.

Transport may also include the movement of liquids by pipeline

and solids by conveyor in specific sectors.

This cell looks at the use of water directly associated with

transport operations. This is mainly water used for cleaning

vehicles (based at sites).

What are the common issues with water within the

supply chain?

The two main issues surrounding water are availability and quality.

Only 0.5% of global water is available as freshwater for human use,

with 97% salt water, and 2.5% locked into glaciers & ice (WCBSD

2009).

With a rapidly growing global population the availability of fresh water

is an increasing problem for many parts of the world. Nearly half of

Europe’s population live in areas defined as ‘water-stressed’ (EEA,

2010).

For more information on the common issues, click here

What are the key issues with water and transport?

Transportation within the supply chain is not a significant user of

water compared to other parts of the supply chain. The majority of

water used in this stage will be for cleaning the different modes of

transport, such as lorries and trains.

Can water be measured?

Water used for cleaning vehicles can be measured through water

metering. Awareness should be raised with staff of the local

impact of water consumption at sites located in water-stressed

regions.

What can be done to reduce the impact and what

are the opportunities?

There are a few processes that can be implemented to reduce the

impact of water use:

• Use recycled water in vehicle washing

• Capture rainwater and store for future use, known as rain water

harvesting

• Train staff to be mindful of water usage

Capturing and treating the waste water associated with this

stage of the chain should be considered, as effluent is likely to

be a significant cost to a site.

Identifying the risks, challenges and potential

pitfalls

The FISS Champions Group on Water report [opens PDF], published

in May 2007 identifies the following challenges for industry:

• Lack of data to enable conclusive economic decisions

• Lack of resources, time and budget

• Uncertainty about financial benefits

• Product quality issues

• Safety and hygiene issues

• Lack of awareness of the technical feasibility of change

• Managing effluent as well as water into facilities

• Be aware of flood risk

For further information on flooding click here.

Where to go for more information

• IGD: Guide to Understanding, Assessing and Managing Water in

Grocery Supply Chains

• WRAP: Water guides

• WRAP: Rippleffect

• Environmental permitting for discharges to surface water and

groundwater

• EA: Food and drink manufacturing industry environmental

management toolkit [opens PDF]

• EA: Water abstraction

• Regional licensing – England and Wales

• EU Water Framework Directive

• Aqueduct - Measuring and mapping water risk

• CEO Water Mandate

• CDP Water Disclosure

• Water Report Library section within igd.com

Relationships of water in transport to other points

in the supply chain

The impact of water use for transportation within the supply chain

will be relatively low compared to other areas of the chain.

Water and transport

back to matrix

page 1 of 1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21e034b0-2dcd-4b88-9663-4ebb36354e65-150715143437-lva1-app6891/85/Environmental_Sustainability_Matrix-4-27-320.jpg)

![BACK TO MATRIX To suggest amends/updates to content, email: Toby.Pickard@igd.com

Please give us feedback

Description of water used in wholesale and retail

This section looks at the use of water directly associated with

wholesale and retail operations. This will include water used for

cleaning (equipment, clothes and personal), catering/cooking

and washing of buildings and vehicles (based at sites) and

toilets.

What are the common issues with water within the

supply chain?

The two main issues surrounding water are availability and

quality. Only 0.5% of global water is available as freshwater for

human use, with 97% salt water, and 2.5% locked into glaciers &

ice (WCBSD 2009).

With a rapidly growing global population the availability of fresh

water is an increasing problem for many parts of the world.

Nearly half of Europe’s population live in areas defined as ‘water-

stressed’ (EEA, 2010).

For more information on the common issues, click here.

What are the key issues with water and wholesale

and retail?

Wholesale and retail are not significant users of water relative to

the whole supply chain, for more information click here.

Nonetheless, measures to reduce water use should be explored.

Perhaps the greatest direct water related threat to wholesale and

retail sites is due to risk of flooding, which can have a significant

impact on operations. For further information on flooding click

here.

Can water be measured?

The water used in wholesale and retail sites can be measured

through water metering. Awareness should also be raised of the

local impact of water consumption if the wholesale or retail site

is located in a water-stressed region. Facilities should also

consider the impact that effluent (waste water) will have on local

systems and networks.

What can be done to reduce the impact and what

are the opportunities?

There are a number of strategies to reduce the impact of water

in wholesale and retail:

• Sub-metering, monitoring and targeting, water mapping

• Identification and repair of leaks

• Provide plugs for sinks, fit percussion taps, dual and

waterless toilet facilities, ‘hippos’ in existing facilities

• Cleaning – Cleaning in Place (CIP) – water recirculation

• Recycle water in car and vehicle washing

• Capture rainwater and store for future use, known as rain

water harvesting

• Reduce run-off, to reduce the impact of heavy rain (and

snow) on local communities

• Use ponds to collect storm water

• Staff training to be mindful of water usage

A useful exercise is to conduct a water balance of a wholesale or

retail site to help identify all areas of consumption and assess

losses through leakage and evaporation which can be harder to

directly measure (see figure 3).

Identifying the risks, challenges and potential

pitfalls

The FISS Champions Group on Water report [opens PDF],

published in May 2007 identifies the following challenges for

industry:

• Lack of data to enable conclusive economic decisions

• Lack of resources, time and budget

• Uncertainty about financial benefits

• Product quality issues

• Safety and hygiene issues

• Lack of awareness of the technical feasibility of change

• Customers’ perceptions and potential risks associated with

change

• Fear of potential negative public relations associated with the

above

• Managing effluent as well as water into facilities

• Be aware of flood risk

Water and wholesale and retail

Figure 3: Diagram of a water mass balance

continues

page 1 of 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21e034b0-2dcd-4b88-9663-4ebb36354e65-150715143437-lva1-app6891/85/Environmental_Sustainability_Matrix-4-28-320.jpg)

![BACK TO MATRIX To suggest amends/updates to content, email: Toby.Pickard@igd.com

Please give us feedback

A report produced by Ceres, UBS and Bloomberg, called MURKY

WATERS? Corporate Reporting on Water Risk: A Benchmarking

Study of 100 Companies, 2010 [opens PDF], concludes that

most companies operating in water-intensive industries are

failing to provide investors with adequate information on the

water-related risks they face and in many cases have little idea

how their supply chains could be affected by water shortages.

Where to go for more information

• IGD: Guide to Understanding, Assessing and Managing Water

in Grocery Supply Chains

• WRAP: Water guides

• WRAP: Rippleffect

• Environmental permitting for discharges to surface water and

groundwater

• EA: Food and drink manufacturing industry environmental

management toolkit [opens PDF]

• EA: Water abstraction

• Regional licensing – England and Wales

• EU Water Framework Directive

• Aqueduct - Measuring and mapping water risk

• CEO Water Mandate

• CDP Water Disclosure

• Water Report Library section within igd.com

Relationships of water in wholesale and retail to

other points in the supply chain

The impact of water use in the wholesale and retail section of

the supply chain will be relatively low compared to other areas of

the chain. However, this doesn’t mean that attempts to reduce

water usage should not be implemented, as significant savings

can be made from relatively easy to implement initiatives, such

as rain water harvesting, staff training and by using more water

efficient machinery.

Water and wholesale and retail

back to matrix

page 2 of 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21e034b0-2dcd-4b88-9663-4ebb36354e65-150715143437-lva1-app6891/85/Environmental_Sustainability_Matrix-4-29-320.jpg)

![BACK TO MATRIX To suggest amends/updates to content, email: Toby.Pickard@igd.com

Please give us feedback

Simple messages where consumers can make a direct impact

work best. For example 99% of the embedded water in a typical

laundry product is derived in the consumer washing phase

(Source: LCA of Ariel ‘actif a froid’ 2006), so filling machines and

using a short cycle is good advice.

In the case of other products, such as soft drinks, 97% of the

embedded water is from raw material (predominantly sugar)

production, so reducing waste and absolute consumption will

have an impact here. However bear in mind there may be trade

offs between reduced water stress that results from reduced

consumption of intensely irrigated products, and the loss of

income that would result within communities that have become

dependent on the crop.

Where to go for more information

• IGD: Guide to Understanding, Assessing and Managing Water

in Grocery Supply Chains

• Water Footprint Network

• WRAP: Down the drain [opens PDF]

• Aqueduct - Measuring and mapping water risk

• Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF): Product water footprint

assessments: Practical application in corporate water

stewardship [opens PDF]

• WWF: Water footprinting: Identifying & addressing water risks

in the value chain [opens PDF]

• Waterwise

• Net Regs: Water discharge regulations

• Water Report Library section within igd.com

Relationships of water and end user and end of life

to other points in the supply chain

Consumers will use a significant amount of water compared to

other points of the supply chain. However, this is a complex area,

as there are challenges to water measurement, cost, time and

interpretation. These challenges could make it difficult to explain

to consumers how to reduce impact.

Water footprint labels have been discussed by academics and

Non Government Organisations as one way of informing

consumers about embedded water within product, and one

European food manufacturer has put a water label on their

product. However, a water label could be misleading if it only

indicates the volume of (embedded) water used in a product

lifecycle and not a measure of water scarcity.

Case studies

• Unilever: Canada: Educating consumers about water

conservation

Water and end user and end of life

back to matrix

page 2 of 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21e034b0-2dcd-4b88-9663-4ebb36354e65-150715143437-lva1-app6891/85/Environmental_Sustainability_Matrix-4-31-320.jpg)

![BACK TO MATRIX To suggest amends/updates to content, email: Toby.Pickard@igd.com

Please give us feedback

End user perception of the issue

According to the Government Review of Waste Policy in England

2011 [opens PDF]: ‘Survey after survey shows that consumers

believe packaging is a big environmental problem.’ Given that

much food and grocery packaging is used and disposed of in

homes it is therefore unsurprising that industry finds itself under

pressure to reduce the amount of packaging used.

However, more often than not this consumer view is a

misconception. Packaging can make a positive impact on the

environment by protecting far more resources than it uses and

preventing far more waste than it generates. According to the

European Commission, packaging accounts for only 5% of waste

(equivalent to 17% of municipal waste) and just 2% of

greenhouse gas emissions in Europe.

Packaging

back to matrix

page 2 of 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21e034b0-2dcd-4b88-9663-4ebb36354e65-150715143437-lva1-app6891/85/Environmental_Sustainability_Matrix-4-33-320.jpg)

![BACK TO MATRIX To suggest amends/updates to content, email: Toby.Pickard@igd.com

Please give us feedback

A waste hierarchy can be used to assess opportunities to reduce

the environmental impact of packaging. A waste hierarchy is

about waste management. It puts preventing waste at the top

and the rest of the options provide guidance on how to handle

waste.

Waste Hierarchy

(Source: Efficient Consumer Response UK)

Prevent:

Options include reducing the weight of transit cases, ordering

ingredients in larger volume formats, investing in bulk handling,

removing inefficient packaging from the process, specifying

packaging targets to suppliers.

Redistribute/Reuse:

Returnable or reusable packaging may provide a major

environmental advantage over one trip/single use packaging. A

feasibility study and life cycle analysis would establish benefits

and comparisons for different applications. Examples of good

practice include the use of returnable, re-useable trays or cases.

Recycle:

Materials used for packaging should be selected for fitness for

purpose, however maximising recyclability and recycled content

often helps minimise materials sent to landfill. In some cases,

this may lead to weight gain rather than reduction so expert

advice may be needed.

Identifying the risks, challenges and potential

pitfalls

• Balance is required when considering alternative materials;

understanding of the supply chain is required to make an

informed decision. For example, physical strength of transit

packaging may be reduced if it contains significant recycled

content

• Re-useable packaging is only feasible and environmentally

beneficial where the infrastructure is in place to transport it

back to source

• There is a lack of viable alternative packaging materials

• Infrastructure to manage/handle new or emerging materials

or systems, investment may be required

Where to go for more information

• Saving money by reducing waste - Waste minimisation

manual: a practical guide for farmers and growers [opens

PDF]

• Agricultural Waste Plastics

• Defra: Farm waste and recycling: Packaging waste

• Learning about agricultural waste

• Environment Agency: Agricultural waste guidance

• Defra guidance to applying the waste management hierarchy

• Defra Packaging Strategy

• ECR UK - Product & Packaging Waste

• Carbon Trust Carbon Footprint Calculator

Relationship of packaging and raw materials to

other points in the supply chain

The most efficient packaging for raw materials can impact

manufacturing efficiencies. Bulk materials may use less material

than small deliveries but investment in bulk handling equipment

may be necessary.

Packaging and raw materials

back to matrix

page 2 of 2

To suggest amends/updates to content, email: Toby.Pick

(Source: Efficient Consumer Response UK)

Prevent or eliminate waste by using Reduce to clear and

the Five-to-drive

Redistribute to alternative markets: surplus for

charities, via clearance houses or for animal feed

Recycle or process into a fresh supply of the same or

similar material and reduce consumption of virgin

material. Recycling

Recover via anaerobic digestion composting, used

cooking oil, rendering, energy recovery and mechanical

heat treatment

Dispose of via landfill, thermal treatment without energy

recovery or via sewer/controlled water course](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21e034b0-2dcd-4b88-9663-4ebb36354e65-150715143437-lva1-app6891/85/Environmental_Sustainability_Matrix-4-35-320.jpg)

![BACK TO MATRIX To suggest amends/updates to content, email: Toby.Pickard@igd.com

Please give us feedback

Wholesalers/retailers and manufacturers can also maximise the

re-use of secondary/tertiary packaging (like the use of

re-useable trays for fresh products) and, where re-useable

packaging is not possible, recycle as much of the secondary and

tertiary packaging that is left on site as possible.

A waste hierarchy can be used to assess opportunities to reduce

the environmental impact of packaging.

Waste Hierarchy

(Source: Efficient Consumer Response UK)

Identifying the risks, challenges and potential

pitfalls

There are potential trade offs between the weight and recycled

content of the packaging material and product damage, shelf life

and product quality. For example, insufficient pallet wrapping

may lead to an increase in likelihood of load movement during

transportation and lightweighted packaging materials may

require more careful handling.

There are very few viable alternative secondary packaging

options. Card is widely used, is recyclable and will contain a

proportion of recycled material.

There may be specific store requirements related to case size and

delivery methods that result in extra packaging. As food and grocery

products typically travel from storage to depot to store by road.

Where to go for more information

• ECR UK - Product & Packaging Waste

• Defra Waste management hierarchy

• Defra Packaging Strategy

• WRAP UK Packaging Benchmark

• WRAP Packaging Research Listings [opens PDF]

• Envirowise Good Practice Guides and Case Studies

• Recoup Recyclability by Design

• Carbon Trust Carbon Footprint Calculator

Relationship of packaging from transport to other

points in the supply chain

The packaging used in the transportation of products must be fit

for purpose; it must protect the product during storage and be

appropriate for wholesalers/retailers to handle in store.

The key environmental sustainability issue associated with

transportation is likely to be its contribution of greenhouse gases

and particulates from moving the packaged goods, rather than

the goods themselves.

Packaging and transport

back to matrix

page 2 of 2

(Source: Efficient Consumer Response UK)

Identifying the risks, challenges and potential

pitfalls

Prevent or eliminate waste by using Reduce to clear and

the Five-to-drive

Redistribute to alternative markets: surplus for

charities, via clearance houses or for animal feed

Recycle or process into a fresh supply of the same or

similar material and reduce consumption of virgin

material. Recycling

Recover via anaerobic digestion composting, used

cooking oil, rendering, energy recovery and mechanical

heat treatment

Dispose of via landfill, thermal treatment without energy

recovery or via sewer/controlled water course](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21e034b0-2dcd-4b88-9663-4ebb36354e65-150715143437-lva1-app6891/85/Environmental_Sustainability_Matrix-4-42-320.jpg)

![BACK TO MATRIX To suggest amends/updates to content, email: Toby.Pickard@igd.com

Please give us feedback

• Re-useable packaging is only feasible and environmentally

beneficial where the infrastructure is in place to transport

the re-useable packaging back to source, and that transport

doesn’t out-weigh the benefit of using single use packaging

• The space and cost of providing recycling infrastructure is a

challenge and requires industry investment. Some councils

offer recycling of certain types of plastics but there is a lack of

consistency across the UK. All types of plastic material can be

recycled but the facilities for collection and recycling for some

materials (e.g. plastic film) are insufficient at present therefore

much of this material continues to go to landfill

• There are potential trade offs between recyclability and shelf

life. For example, skinpacks are often used to increase shelf

life of red meats, but they are often less recyclable than the

trays that they replace. Similarly, thicker packaging to allow

use of a modified atmosphere will compromise weight

reduction

• Some novel materials may cause problems down the line for

recyclers, especially where some biomaterials are used,

either on their own or in combination with conventional

materials

Where to go for more information

• ECR UK - Product & Packaging Waste

• Defra waste management hierarchy

• Defra Packaging Strategy

• WRAP UK Packaging Benchmark

• WRAP Packaging Research Listings [opens PDF]

• Envirowise Good Practice Guides and Case Studies

• Recoup Recyclability by Design

• Carbon Trust Carbon Footprint Calculator

Relationship of packaging in wholesale and retail

to other points in the supply chain

The type of consumer product and how it is packaged in a

wholesaler or retail store is a key influencer of secondary and

tertiary packaging throughout the chain.

How a product is merchandised in store will also have an impact

on the packaging required, especially if it is merchandised in

pallet displays, in pre-packed shipper units and in Retail Ready

Packaging.

Case studies

• Asda - The Packaging Challenge

• Marks & Spencer and Closed Loop Recycling - Office

Recycling

Packaging and wholesale and retail

back to matrix

page 3 of 3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21e034b0-2dcd-4b88-9663-4ebb36354e65-150715143437-lva1-app6891/85/Environmental_Sustainability_Matrix-4-45-320.jpg)

![BACK TO MATRIX To suggest amends/updates to content, email: Toby.Pickard@igd.com

Please give us feedback

Description of packaging used in end user and end

of life

This cell focuses on packaging that is handled by shoppers and

in homes (primary packaging). This packaging performs many

functions: protecting the product, extending its life; and providing

consumer information.

After the product has been consumed the packaging enters the

‘end of life’ stage. The main focus of this stage of the chain is

about enhancing material and energy recovery.

What are the common issues with packaging

within the supply chain?

The EU Directive on packaging and packaging waste, which is

implemented in the UK through two laws: the Responsibility

Regulations (Packaging Waste) and the Packaging (Essential

Requirements) Regulations states that companies are by law

required to use only the minimum amount of packaging

necessary to comply with the necessary level of safety, hygiene

and acceptance for the packed product and for the consumer.

According to the Government Review of Waste Policy in England

2011 [opens PDF]: ‘Survey after survey shows that consumers

believe packaging is a big environmental problem.’ Due to this

industry is often put under pressure to reduce the amount of

packaging used. IGD’s research also finds that packaging is a

major concern for consumers. To find out more click here.

For more information about common issues, click here.

What are the issues with packaging and end user

and end of life?

The issue is minimising the environmental impact of packaging,

whilst keeping it fit-for purpose in terms of product protection

and as a communication medium.

Correct selection of packaging will maintain, or even enhance,

the quality and shelf life of many products. Poor selection can

easily compromise quality and shelf life, potentially leading to

product waste, which increases the environmental impact of the

product.

With packaging having such a tangible and visible aspect for the

consumer, there is often pressure on industry to reduce it. It is a

challenge to do this without compromising product protection or

product shelf life.

Customers are increasingly aware of and concerned about