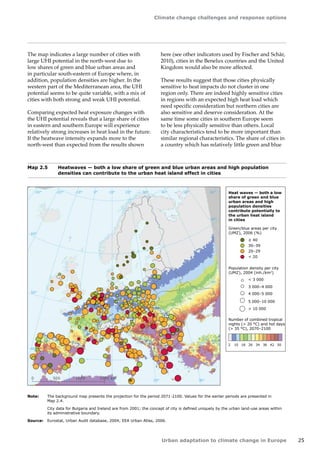

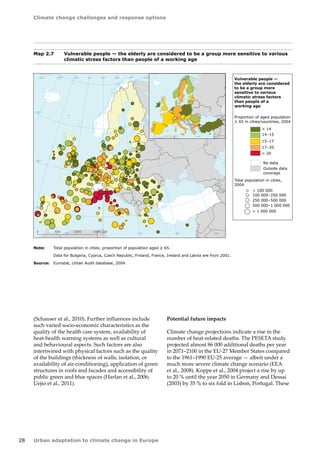

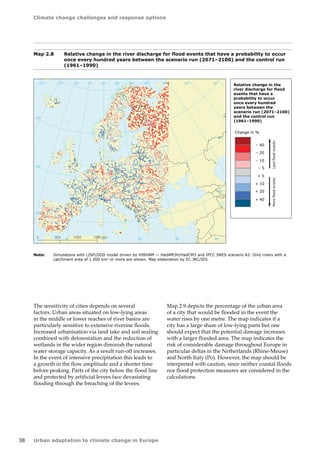

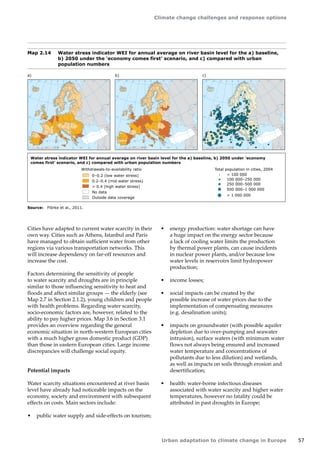

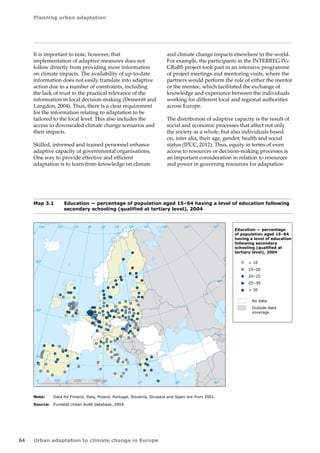

This report discusses the challenges of climate change adaptation for European cities. It finds that rising temperatures will increase heat stress, flooding is expected to become more frequent and severe, and water scarcity may affect many urban areas. The report outlines response options for cities to adapt, such as green infrastructure, cool roofs, flood protection, and water efficiency. It emphasizes the importance of coordinated adaptation planning across sectors and governance levels. National and EU policies can help enable local action through frameworks, funding, and knowledge sharing.