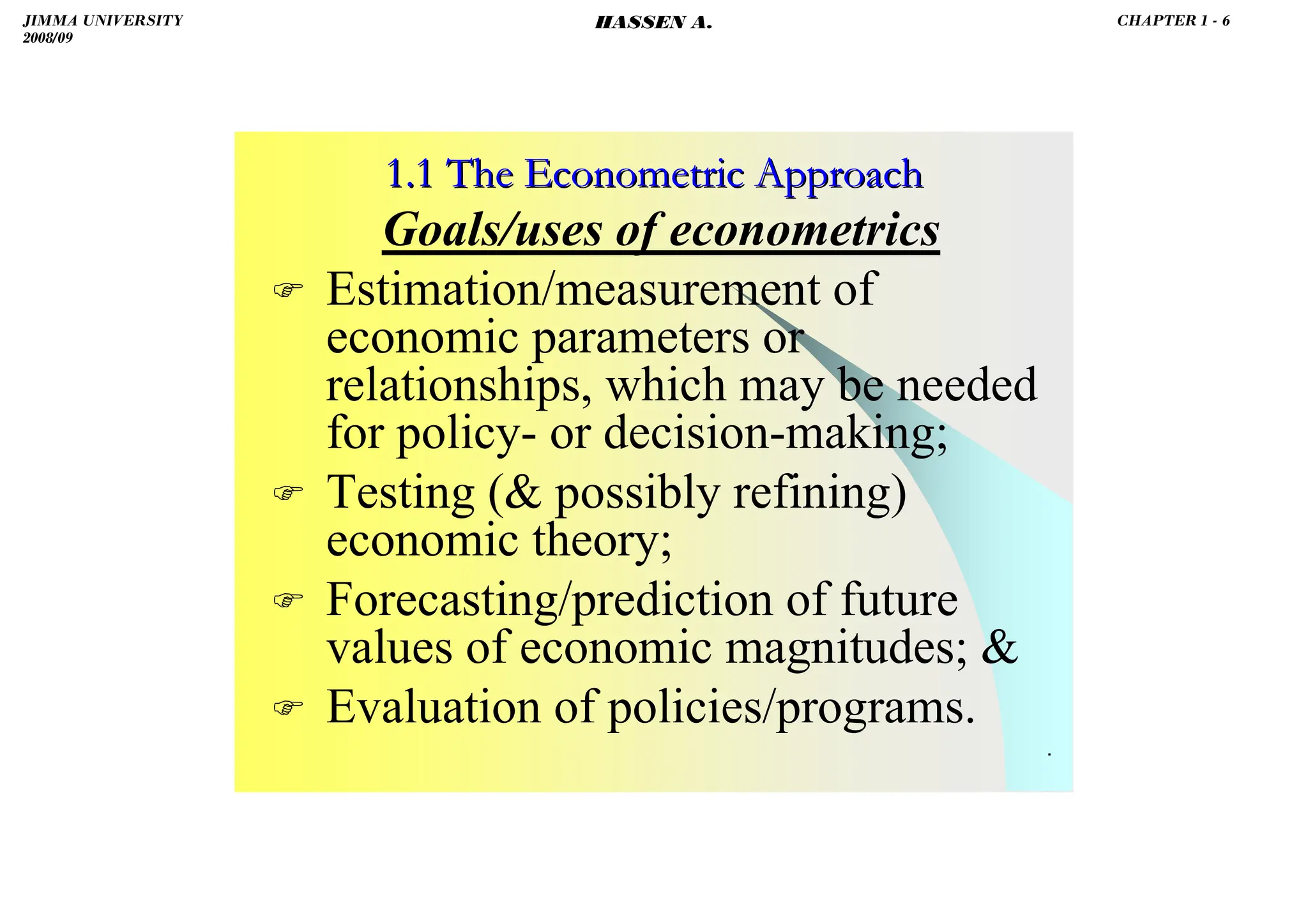

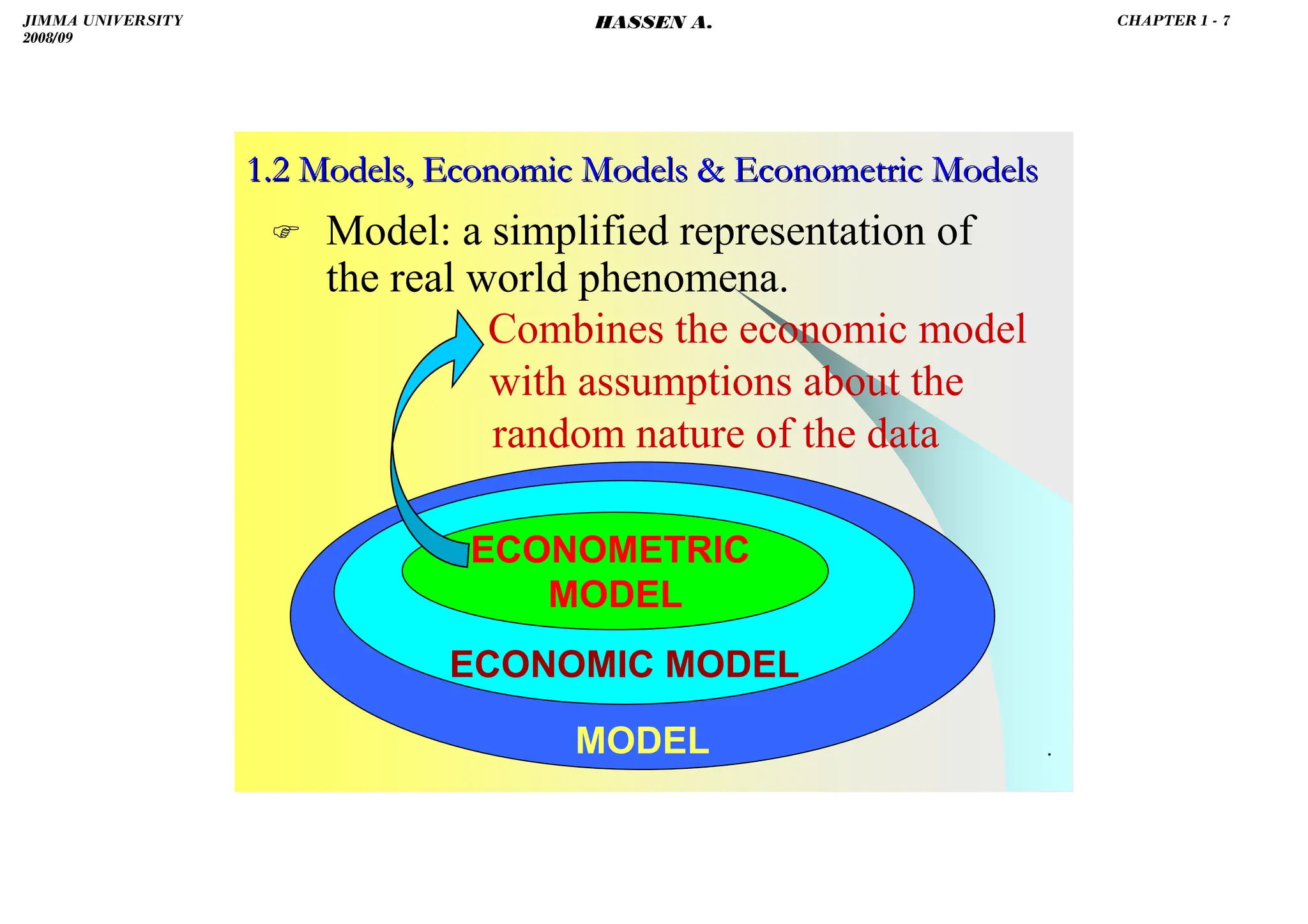

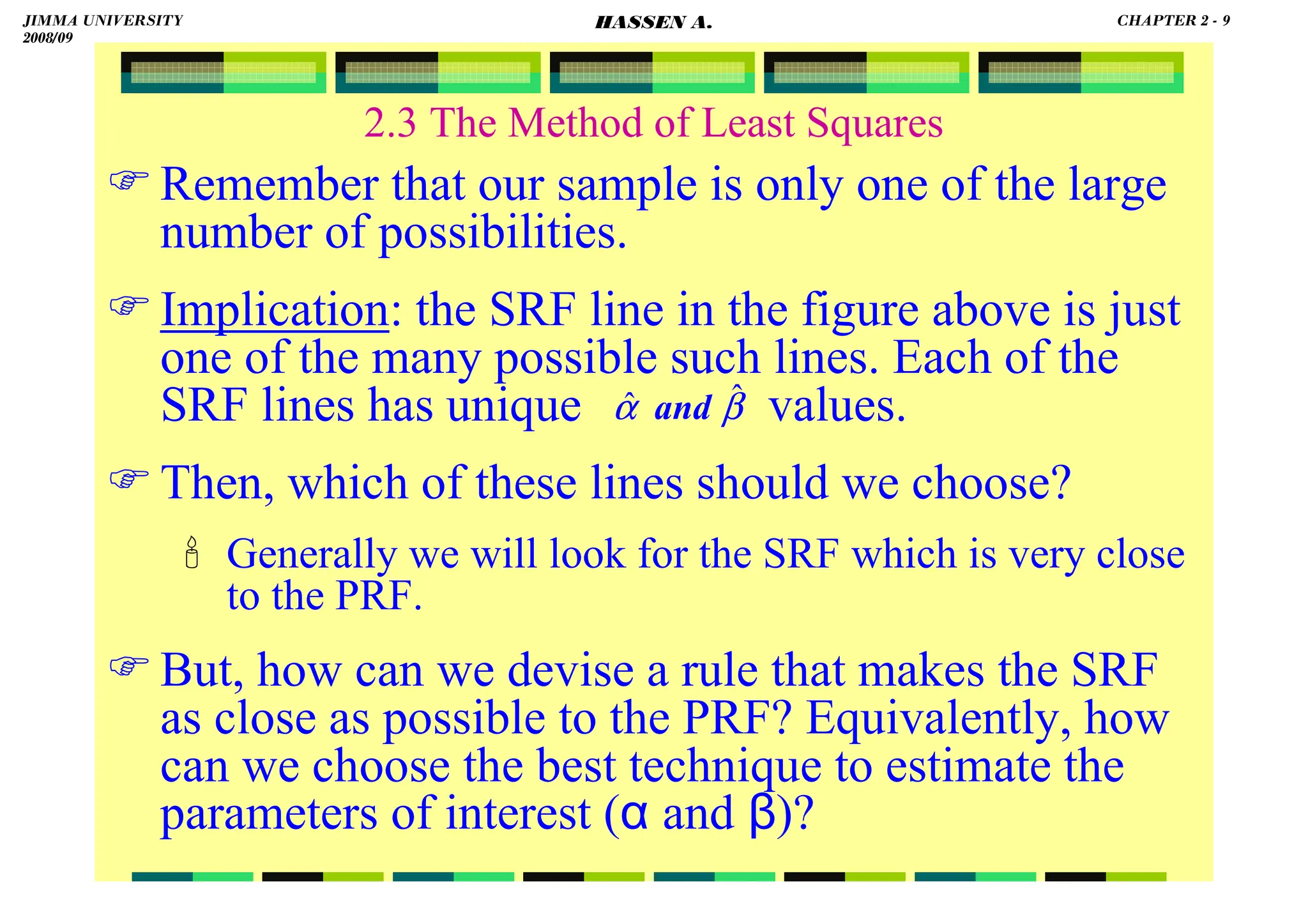

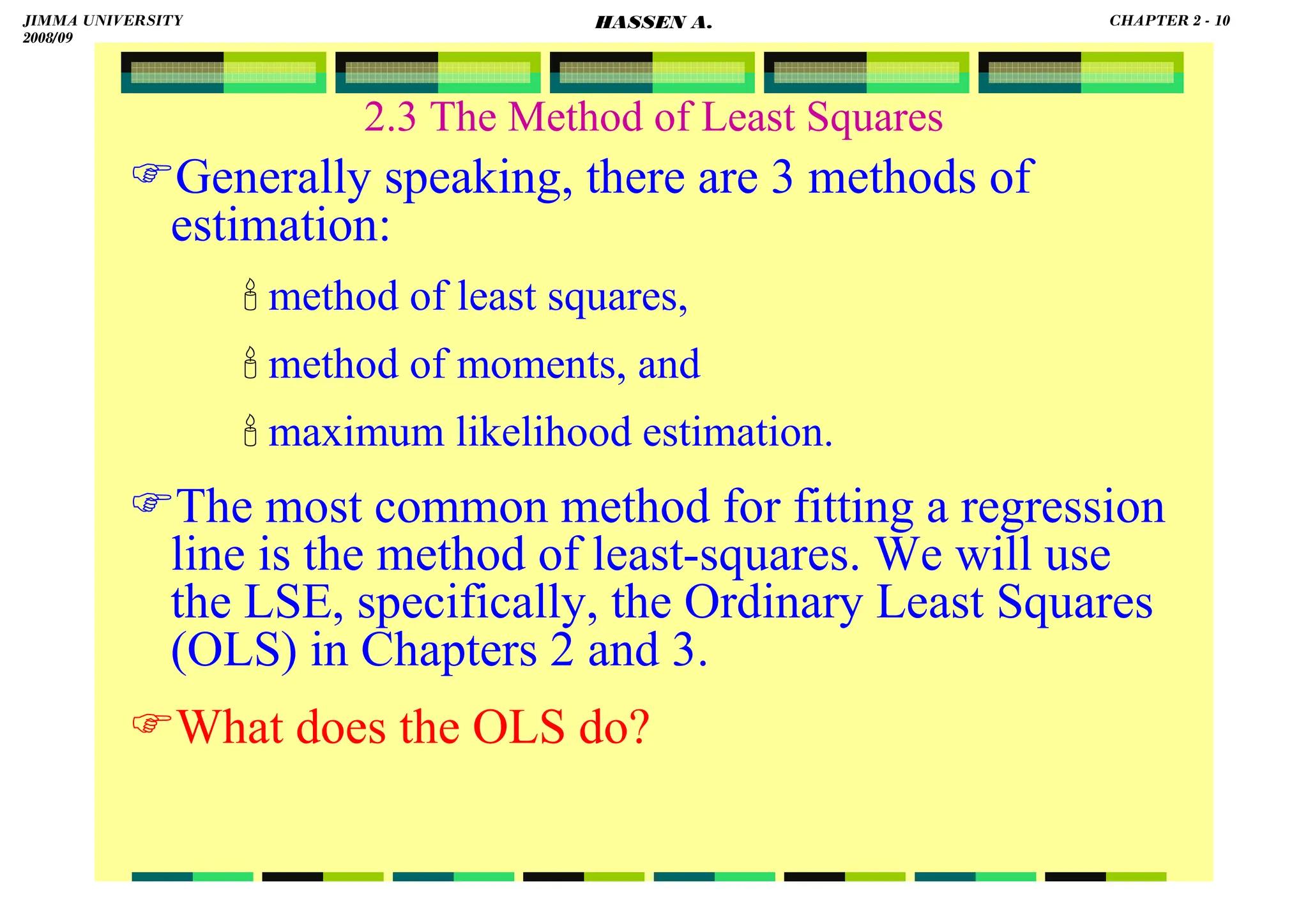

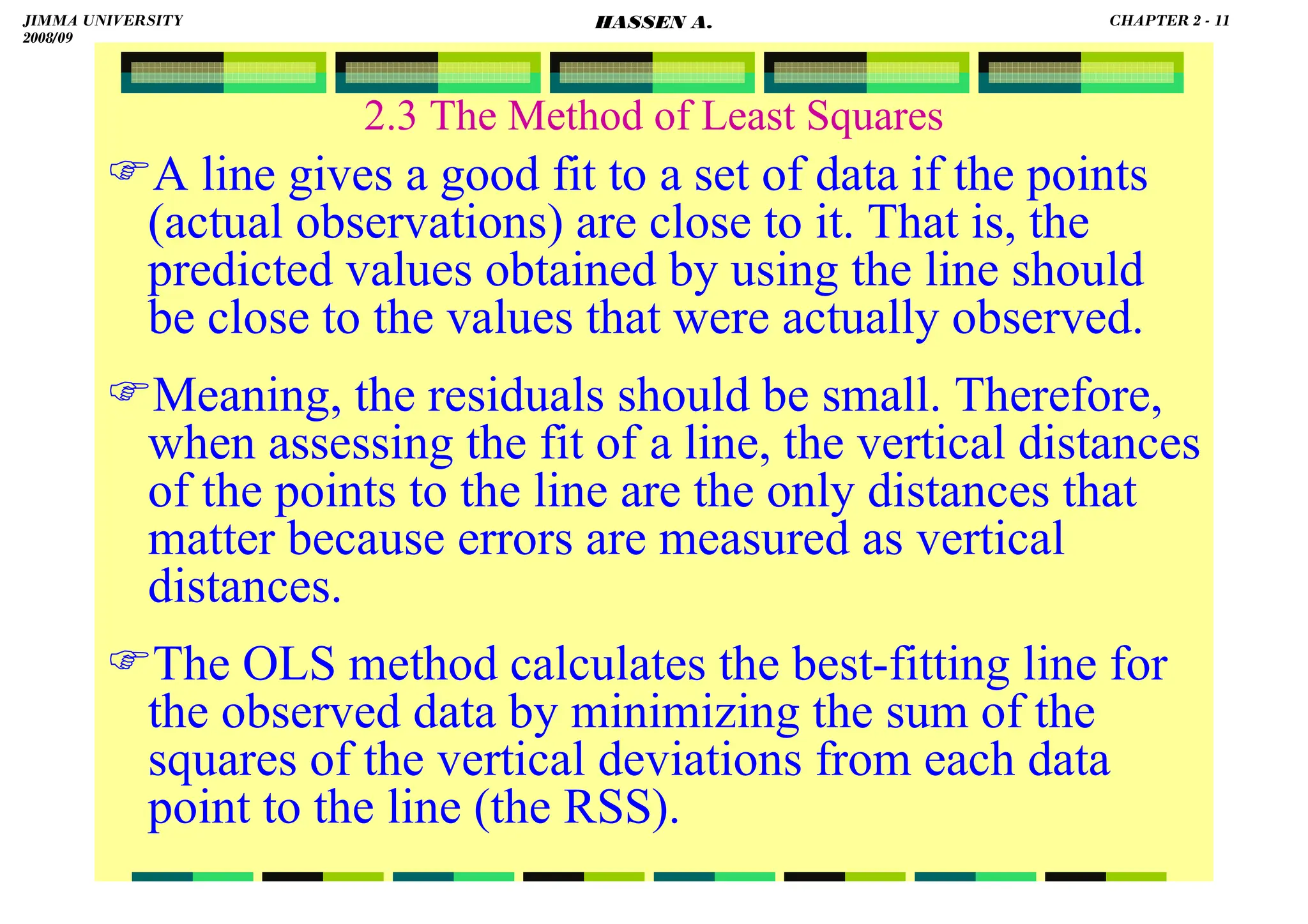

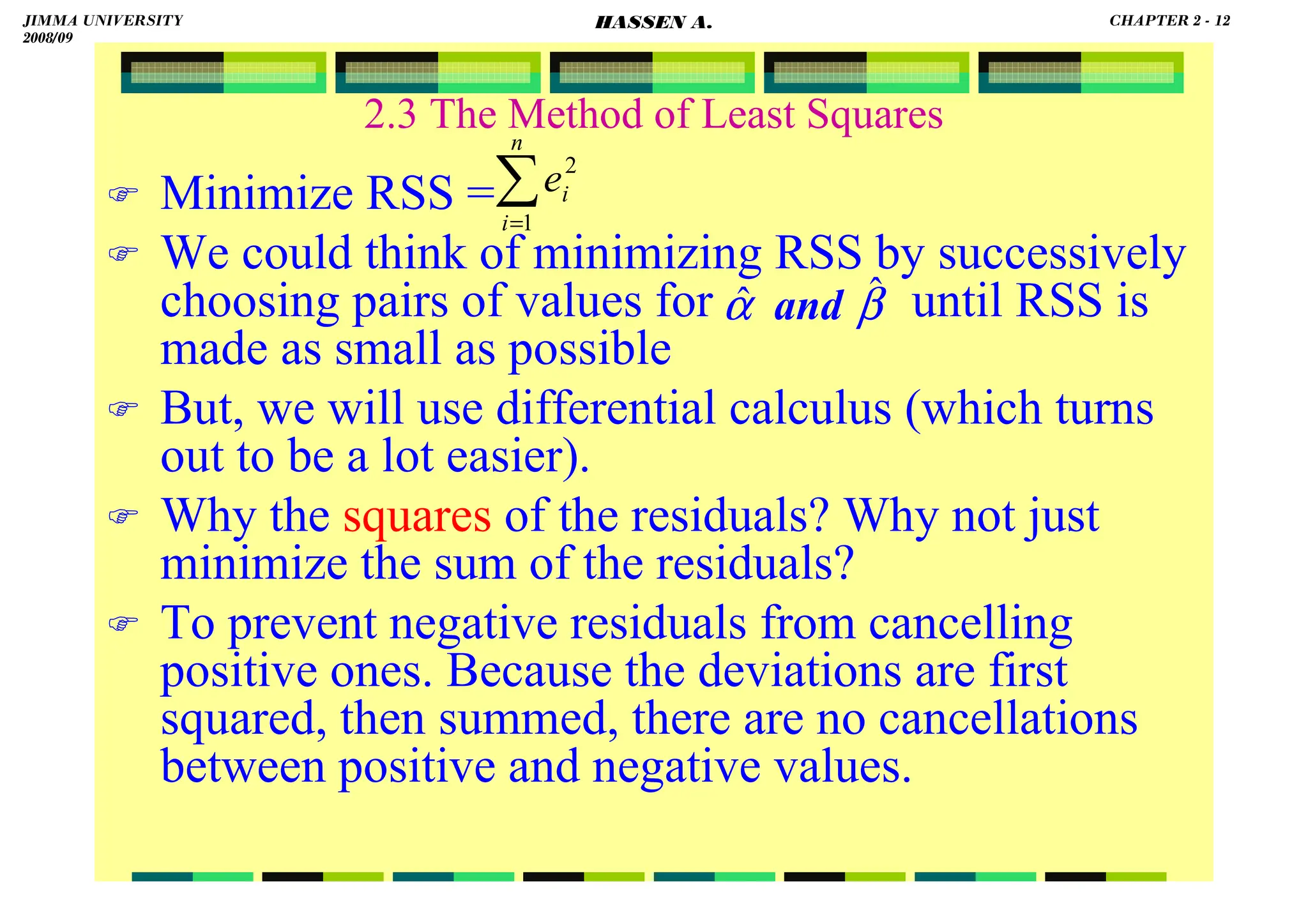

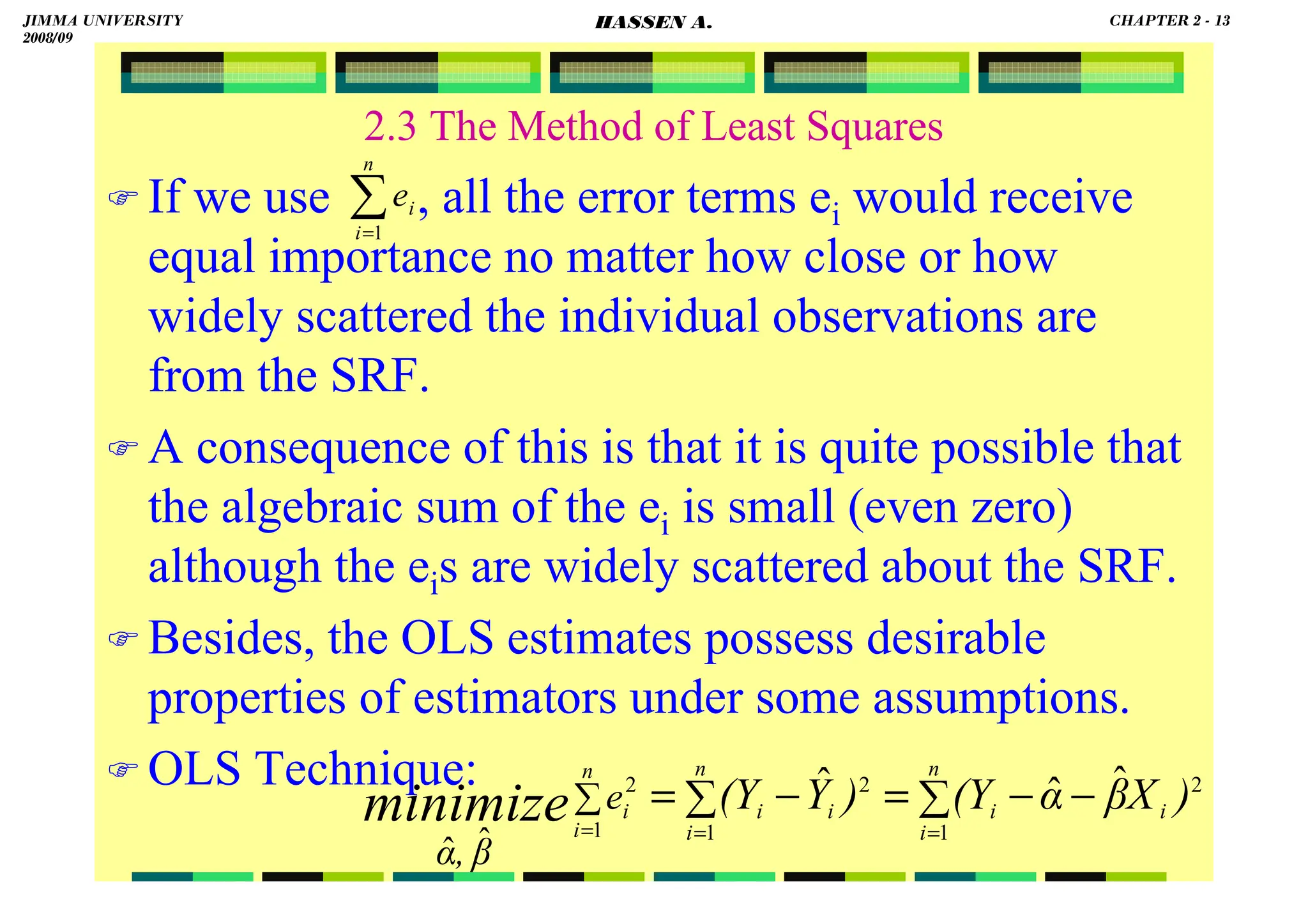

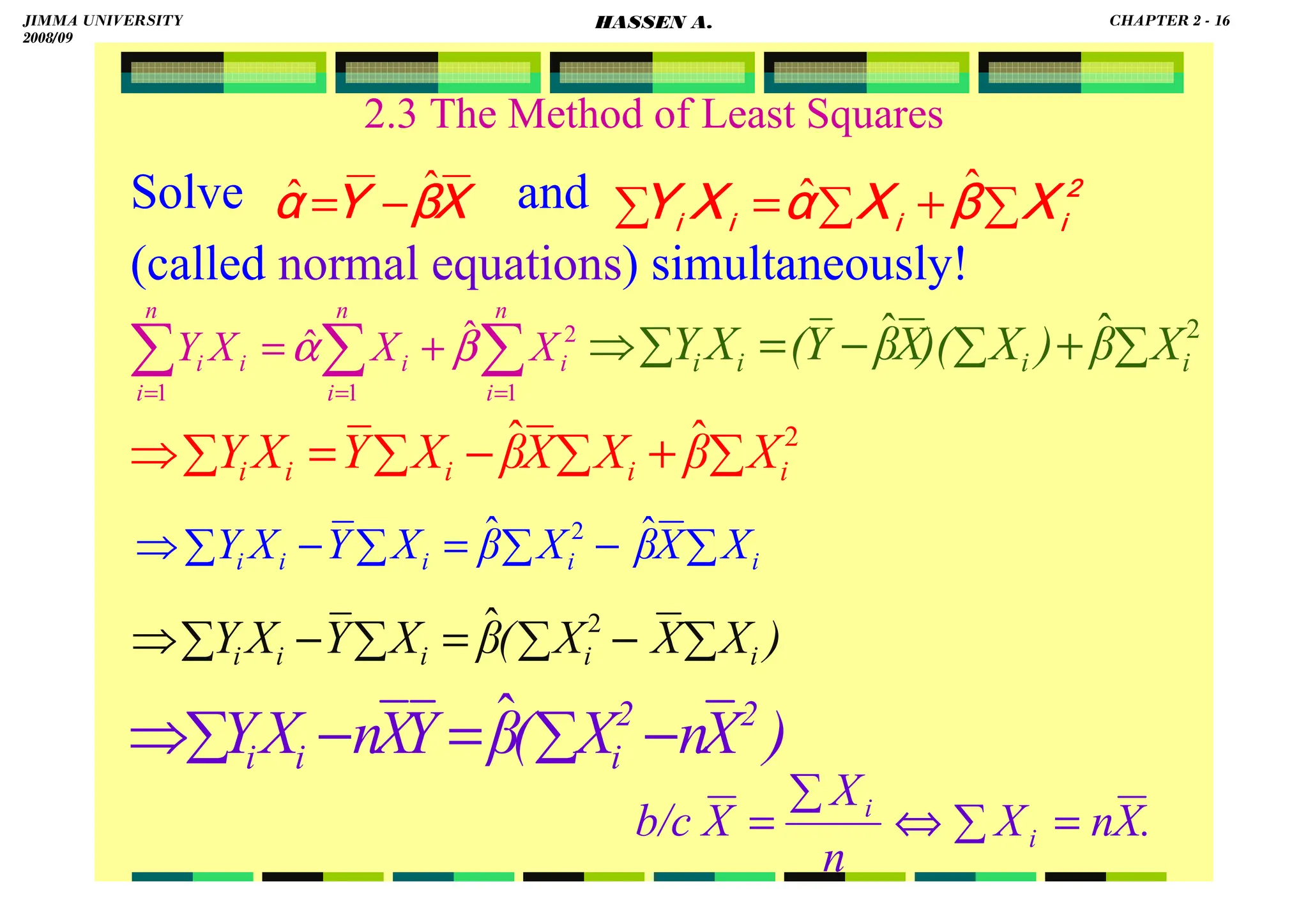

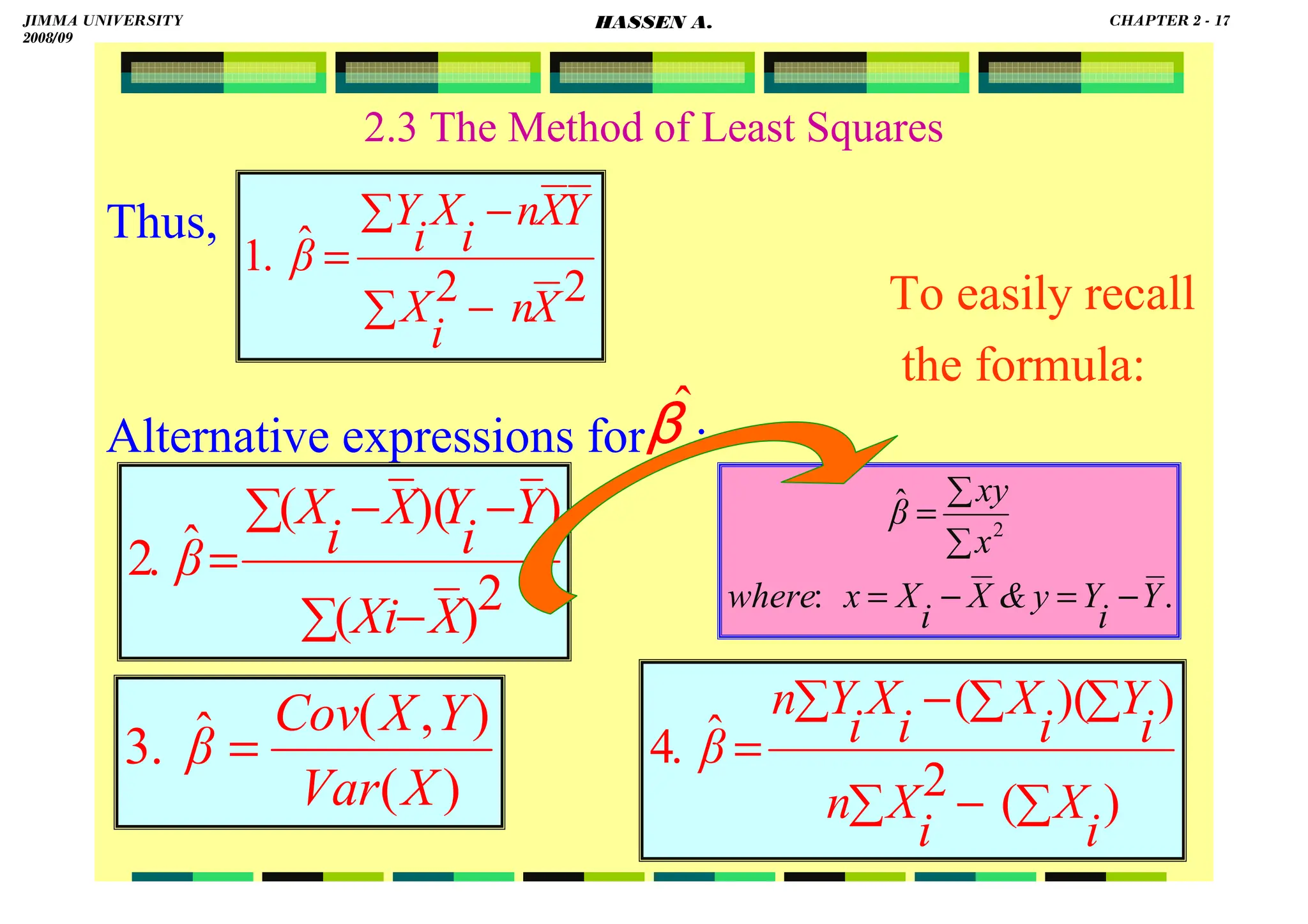

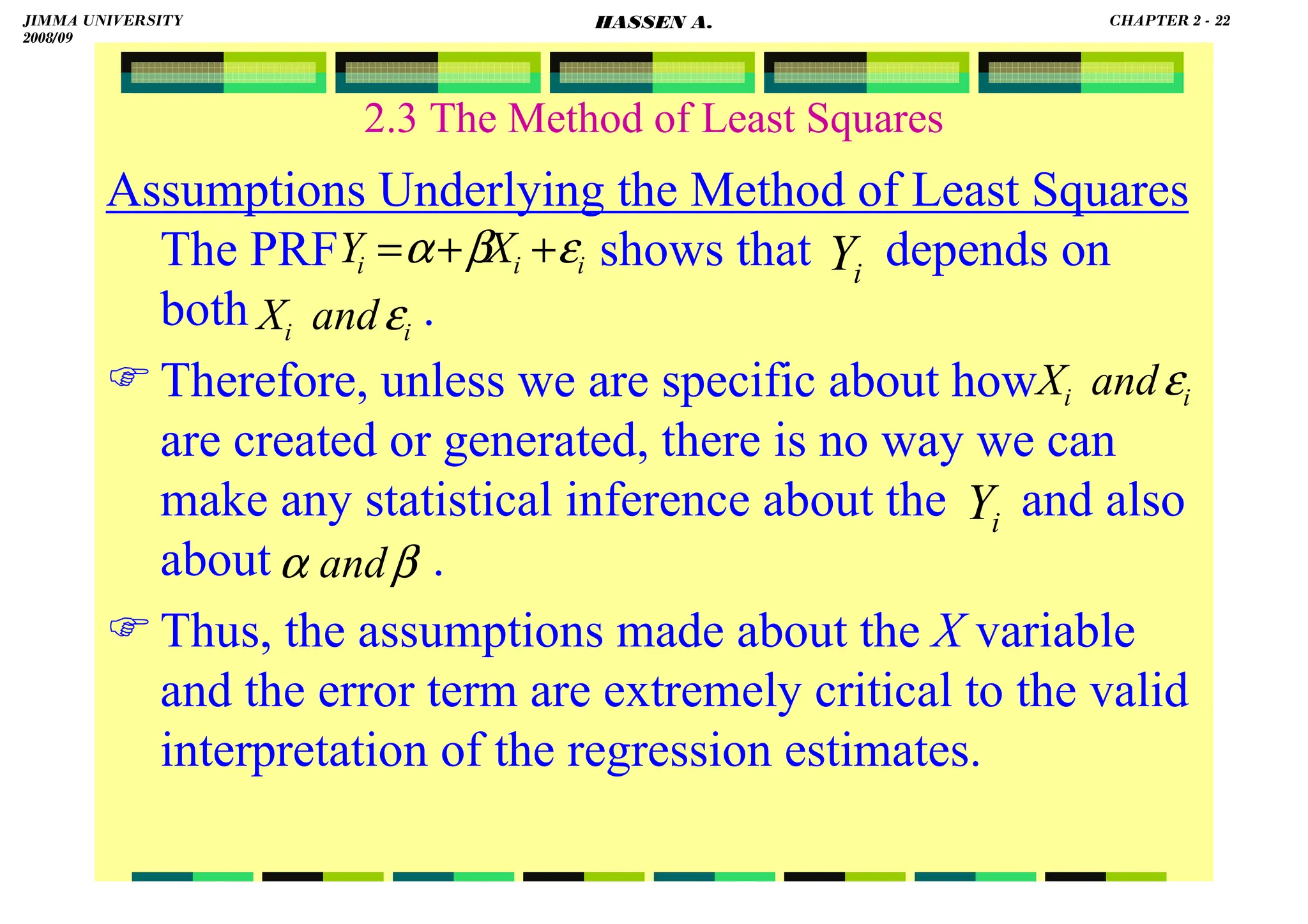

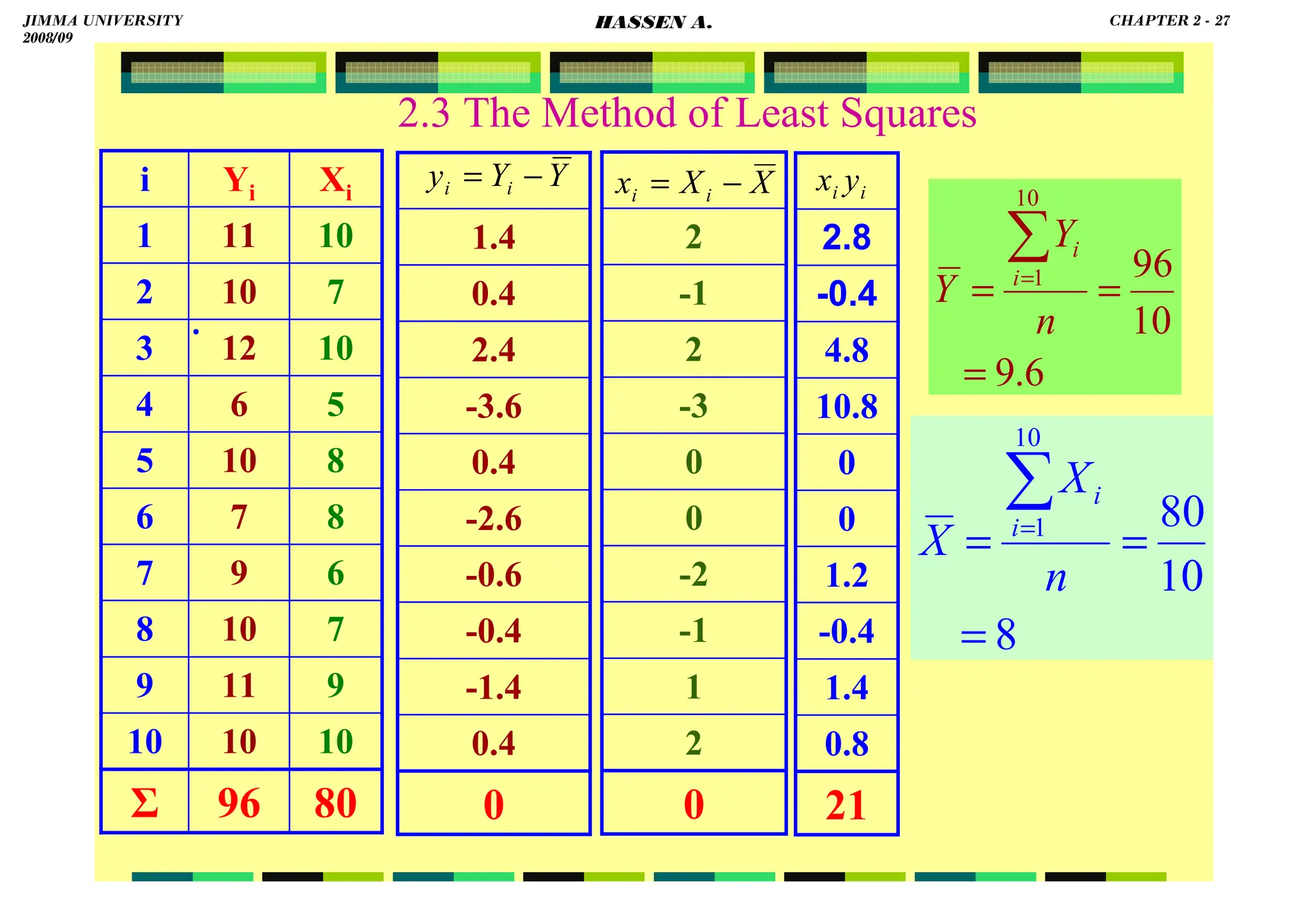

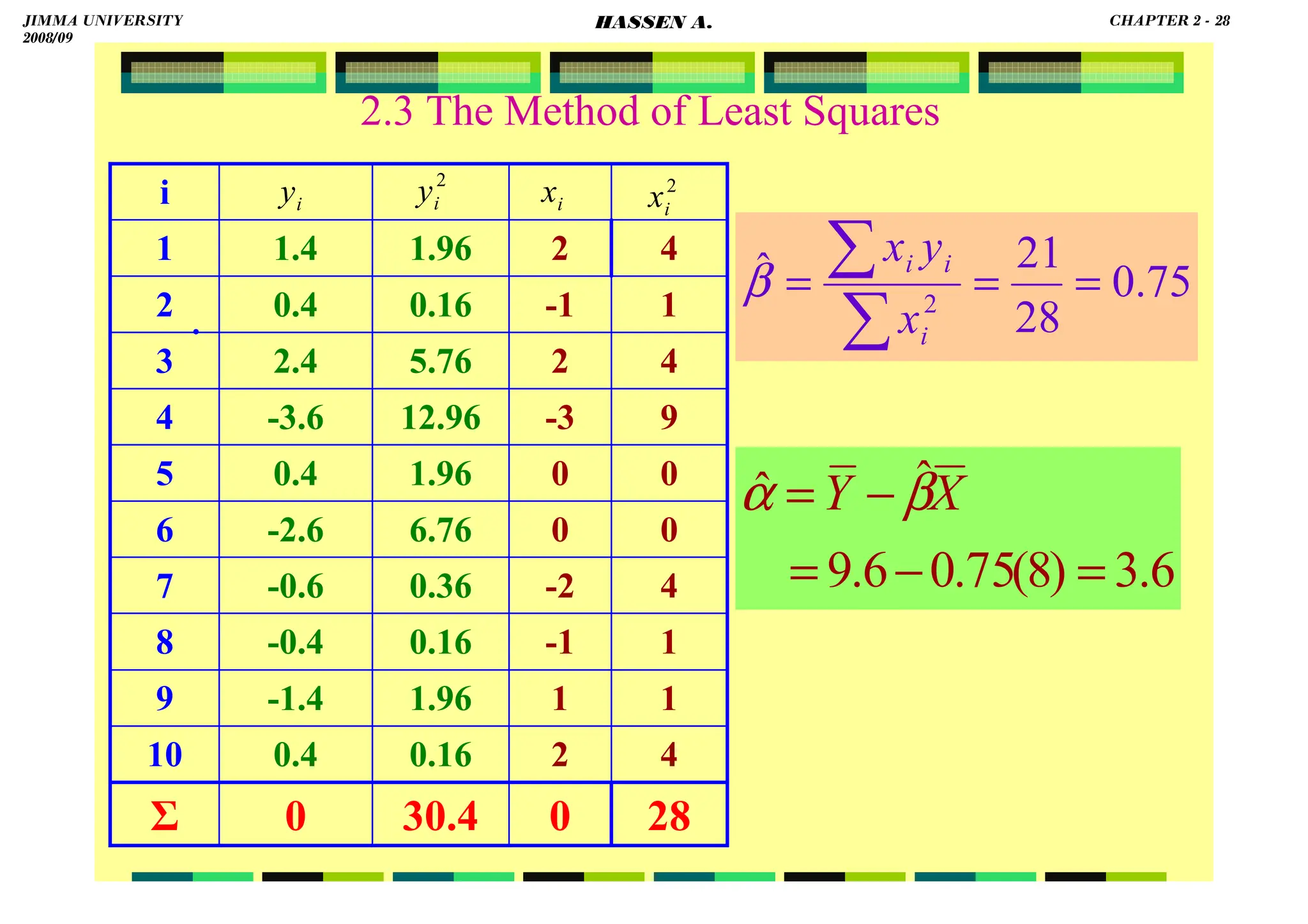

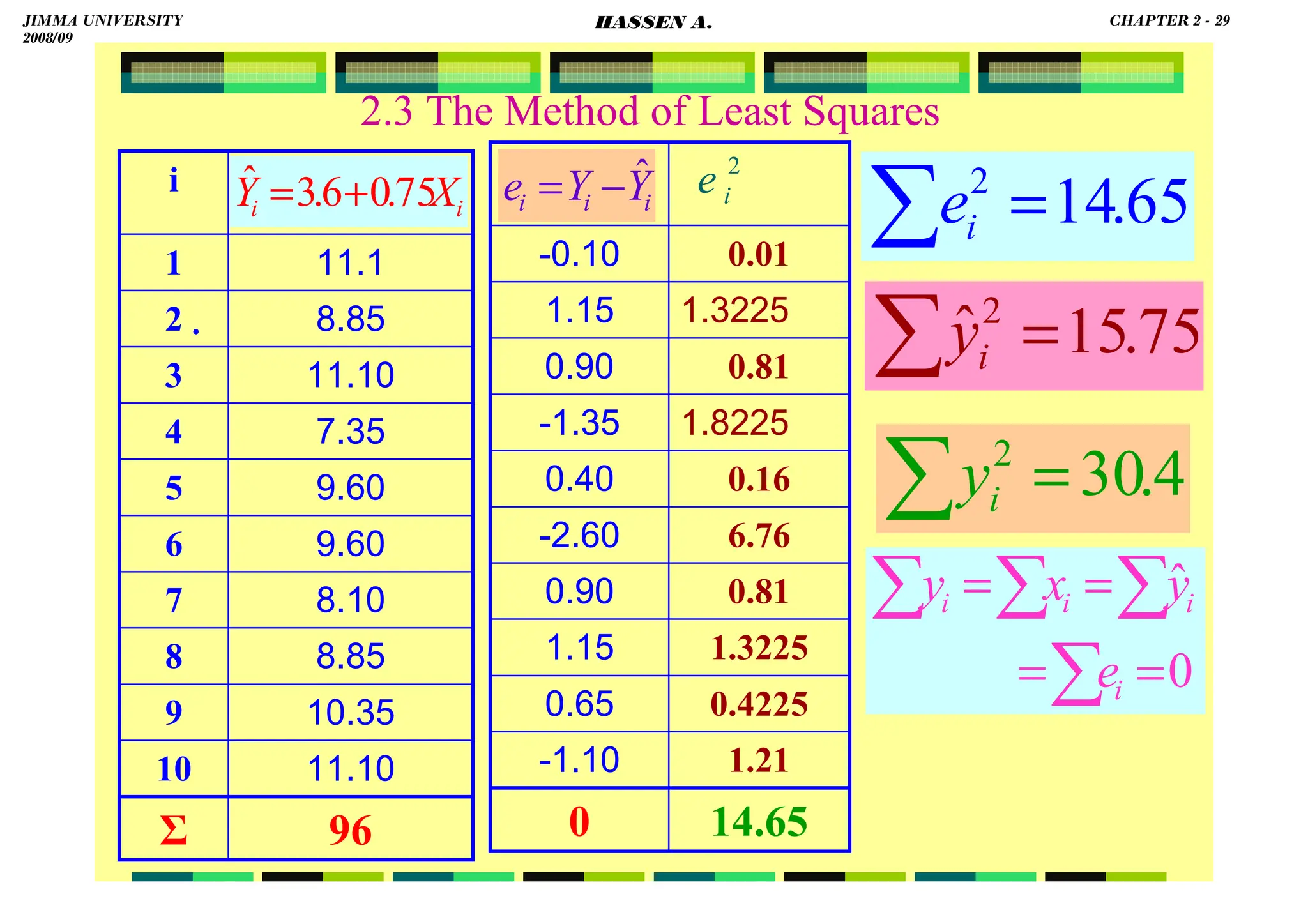

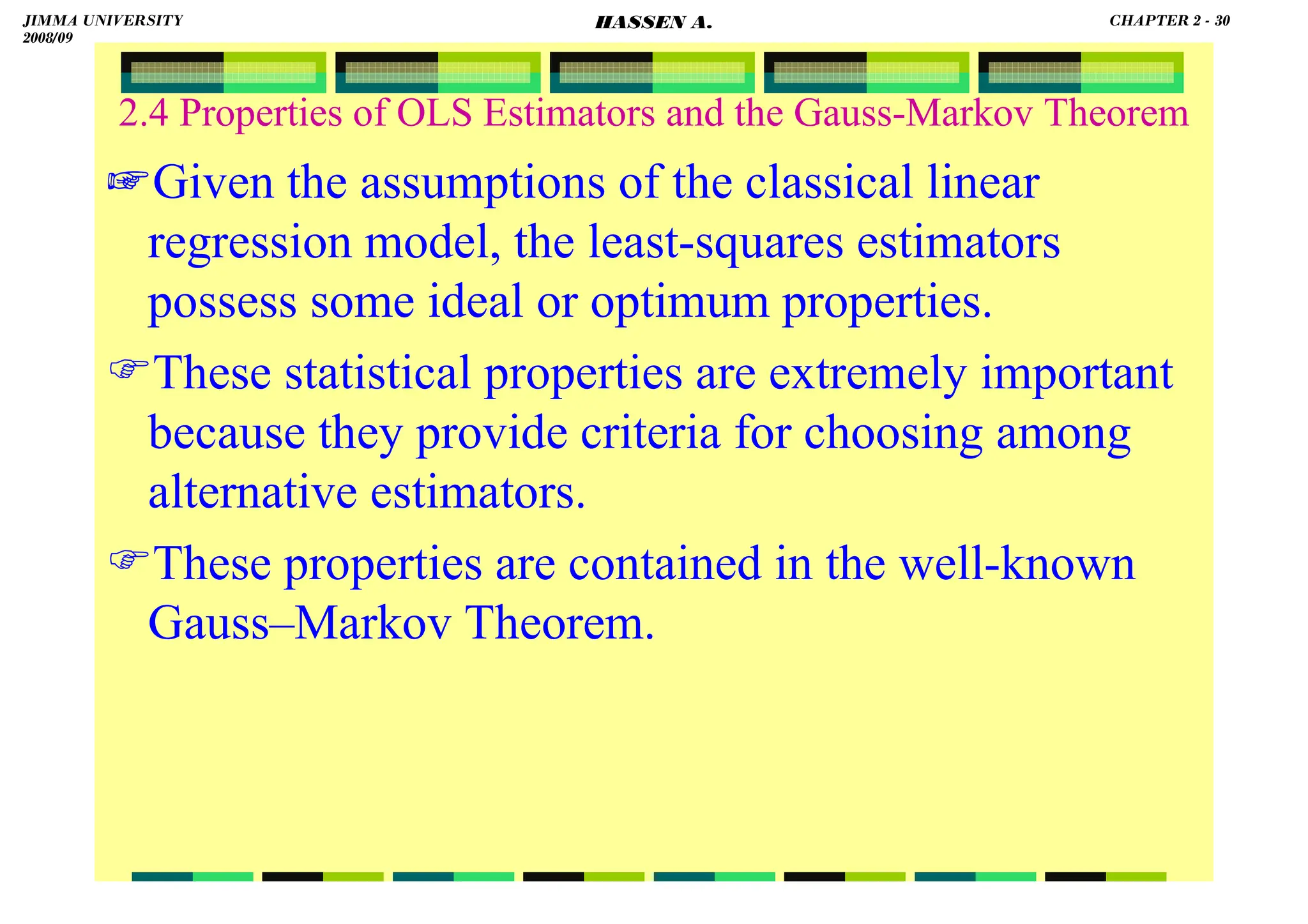

The document serves as an introduction to econometrics and its application in economic measurement through the use of statistical methods and theories. It covers key concepts such as econometric models, types of data, and regression analysis, emphasizing the importance of estimation, hypothesis testing, and policy evaluation. The text also highlights the method of least squares for fitting regression lines and the significance of understanding relationships between economic variables.

![HASSEN ABDA

2.1 The Concept of Regression Analysis

Origin of the word regression!

Our objective in regression analysis is to find out

how the average value of the dependent variable (or

the regressand) varies with the given values of the

explanatory variable (or the regressor/s).

Compare regression correlation! (dependence vs.

association).

The key concept underlying regression analysis is

the conditional expectation function (CEF), or

population regression function (PRF).

)

(

]

|

[ i

i X

f

X

Y

E =

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 2 - 2

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-15-2048.jpg)

![HASSEN ABDA

2.1 The Concept of Regression Analysis

For empirical purposes, it is the stochastic PRF that

matters.

The stochastic disturbance term ɛi plays a critical

role in estimating the PRF.

The PRF is an idealized concept, since in practice

one rarely has access to the entire population.

Usually, one has just a sample of observations.

Hence, we use the stochastic sample regression

function (SRF) to estimate the PRF, i.e., we

use: to estimate .

i

i

i X

Y

E

Y ε

+

= ]

|

[

)

i

e

,

i

Y

f

i

Y ˆ

(

= )

i

e

,

i

X

Y

E

f

i

Y

]

|

[

(

=

)

f(X

Y i

i =

ˆ

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 2 - 3

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-16-2048.jpg)

![HASSEN ABDA

.

2.2 The Simple Linear Regression Model

We assume linear PRFs, i.e., regressions that are

linear in parameters (α and β). They may or may not

be linear in variables (Y or X).

Simple because we have only one regressor (X).

Accordingly, we use:

.

,

ˆ

,

ˆ

ly

respective

,

and

of

estimates

re

sample

a

from

and

i

a

i

e

ε

β

α

β

α

⇒

.

i

i X

X

Y

E

estimate

to

i

X

i

Y β

α

β

α +

=

+

= ]

|

[

ˆ

ˆ

ˆ

i

i X

X

Y

E β

α+

=

]

|

[ i

i

i X

Y ε

β

α +

+

=

⇒

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 2 - 4

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-17-2048.jpg)

![HASSEN ABDA

2.2 The Simple Linear Regression Model

From the PRF:

From the SRF:

i

i

i X

Y

E

Y i

ε

+

= ]

|

[

i

e

i

Y

i

Y +

= ˆ

]

|

[ i

i

i X

Y

E

Y i

−

=

ε

i

i

i X

X

Y

E

but β

α +

=

]

|

[

,

iiii

iiii

iiii

β

X

β

X

β

X

β

X

αααα

YYYY

εεεε

−

−

=

i

i

i Y

Y

e ˆ

−

=

i

X

Y

but i β

α ˆ

ˆ

ˆ +

=

iiii

XXXX

ββββ

αααα

YYYY

eeee

iiii

iiii

ˆ

ˆ −

−

=

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 2 - 6

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-19-2048.jpg)

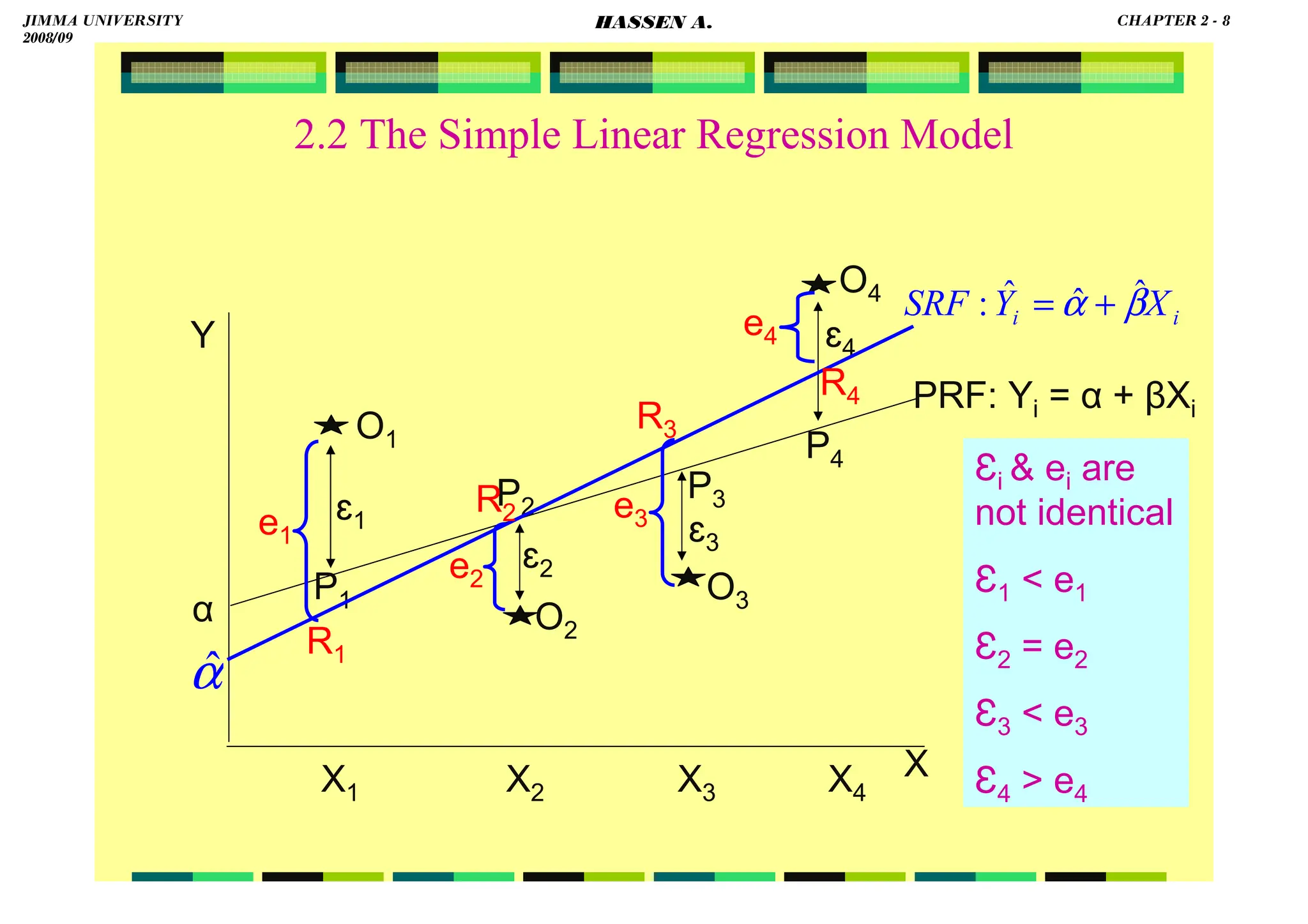

![HASSEN ABDA

2.2 The Simple Linear Regression Model

O1 P4

α

X

P3

P2

O4

O3

O2

P1

E[Y|Xi] = α + βXi

Y

ɛ1

ɛ2

ɛ3

ɛ4

X1 X2 X3 X4

E[Y|X2] = α + βX2

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 2 - 7

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-20-2048.jpg)

![HASSEN ABDA

2.3 The Method of Least Squares

F.O.C.: (1)

0

ˆ

]

)

ˆ

ˆ

(

[

0

ˆ

)

(

1

2

1

2

=

∂

−

−

∂

⇒

=

∂

∂ ∑

∑ =

=

α

β

α

α

n

i

i

i

n

i

i X

Y

e

0

]

1

][

)

ˆ

ˆ

(

.[

2

1

=

−

−

−

⇒ ∑

=

n

i

i

i X

Y β

α

0

)

ˆ

ˆ

(

1

=

−

−

⇒ ∑

=

n

i

i

i X

Y β

α

0

ˆ

ˆ

1

1

1

=

−

−

⇒ ∑

∑

∑ =

=

=

n

i

i

n

i

n

i

i X

Y β

α

0

ˆ

ˆ =

−

−

⇒ X

Y β

α

XXXX

ββββ

YYYY

αααα

ˆ

ˆ −

=

⇒

.

0

ˆ

ˆ

1

1

=

−

−

⇒ ∑

∑ =

=

n

i

i

n

i

i X

n

Y β

α

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 2 - 14

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-27-2048.jpg)

![HASSEN ABDA

2.3 The Method of Least Squares

F.O.C.: (2)

0

ˆ

]

)

ˆ

ˆ

(

[

0

ˆ

)

(

1

2

1

2

=

∂

−

−

∂

⇒

=

∂

∂ ∑

∑ =

=

β

β

α

β

n

i

i

i

n

i

i X

Y

e

0

]

][

)

ˆ

ˆ

(

.[

2

1

=

−

−

−

⇒ ∑

=

i

n

i

i

i X

X

Y β

α

0

)]

(

)

ˆ

ˆ

[(

1

=

−

−

⇒ ∑

=

i

n

i

i

i X

X

Y β

α

0

ˆ

ˆ

1

2

1

1

=

−

−

⇒ ∑

∑

∑ =

=

=

n

i

i

n

i

i

i

n

i

i X

X

X

Y β

α

∑

∑

∑ =

=

=

+

=

⇒

n

i

i

n

i

i

i

n

i

i X

X

X

Y

1

2

1

1

ˆ

ˆ β

α

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 2 - 15

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-28-2048.jpg)

![HASSEN ABDA

18

2.3 The Method of Least Squares

for just use:

Or, if you wish:

XXXX

ββββ

YYYY

αααα

ˆ

ˆ −

=

]}

2

X

n

2

i

X

Y

X

n

i

X

i

Y

.[

X

{

Y

α

−

∑

−

∑

−

=

ˆ

2

X

n

2

i

X

i

X

i

Y

X

2

i

X

Y

α

−

∑

∑

−

∑

=

⇒ ˆ

2

X

n

2

i

X

]

Y

2

X

n

i

X

i

Y

X

Y

]

2

X

n

2

i

X

α

−

∑

−

∑

−

−

∑

=

⇒

[

[

ˆ

2

X

n

2

i

X

Y

2

X

n

i

X

i

Y

X

Y

2

X

n

2

i

X

Y

α

−

∑

+

∑

−

−

∑

=

⇒ ˆ

)

(

)

)(

(

)

)(

(

ˆ

2

X

n

2

i

X

n

i

X

i

Y

i

X

2

i

X

i

Y

α

−

∑

∑

∑

−

∑

∑

=

⇒

αααα

ˆ

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 2 - 18

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-31-2048.jpg)

![HASSEN ABDA

19

2.3 The Method of Least Squares

Previously, we came across the following two

normal equations:

this is equivalent to:

equivalently,

Note also the following property:

0

)]

(

)

ˆ

ˆ

[(

1

=

−

−

∑

=

i

n

i

i

i X

X

Y

2. β

α

0

)

ˆ

ˆ

(

.

1

1

=

−

−

∑

=

n

i

i

i X

Y β

α 0

1

=

∑

=

n

i

i

e

0

1

=

∑

=

n

i

i

i X

e

i

e

i

Y

i

Y +

= ˆ

Y

Y ˆ

=

n

i

e

n

i

Y

n

i

Y ∑

∑

∑

+

=

⇒

ˆ

∑

∑

∑ +

=

⇒

i

e

i

Y

i

Y ˆ

.

0

0

ˆ =

⇔

=

=

⇒ ∑ e

i

e

since

Y

Y

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 2 - 19

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-32-2048.jpg)

![HASSEN ABDA

2.3 The Method of Least Squares

Assumptions Underlying the Method of Least Squares

To obtain the estimates of α and β, assuming that

our model is correctly specified and that the

systematic and the stochastic components in the

equation are independent suffice.

But the objective in regression analysis is not only

to obtain but also to draw inferences about

the true . For example, we’d like to know

how close are to or to .

To that end, we must not only specify the functional

form of the model, but also make certain assumps

about the manner in which are generated.

i

Y

]

|

[ i

X

Y

E

i

Ŷ

β

α ˆ

ˆ and

β

α ˆ

ˆ and

β

α and

β

α and

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 2 - 21

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-34-2048.jpg)

![HASSEN ABDA

2.3 The Method of Least Squares

THE ASSUMPTIONS:

1. Zero mean value of disturbance, ɛi: E(ɛi|Xi) = 0.

Or equivalently, E[Yi|Xi] = α + βXi.

2. Homoscedasticity or equal variance of ɛi. Given the

value of X, the variance of ɛi is the same (finite

positive constant σ2) for all observations. That is,

var(ɛi|Xi) = E[ɛi–E(ɛi|Xi)]2 = E(ɛi)2 = σ2.

By implication: var(Yi|Xi) = σ2.

var(Yi|Xi) = E{α+βXi+ɛi – (α+βXi)}2

= E(ɛi)2

= σ2 for all i.

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 2 - 23

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-36-2048.jpg)

![HASSEN ABDA

2.3 The Method of Least Squares

3. No autocorrelation between the disturbance terms.

Each random error term ɛi has zero covariance

with, or is uncorrelated with, each and every other

random error term ɛs (for s ≠ i).

cov(ɛi,ɛs|Xi,Xs) = E{[ɛi−E(ɛi)]|Xi}{[ɛs−E(ɛs)]|Xs} =

E(ɛi|Xi)(ɛs|Xs) = 0.

Equivalently, cov(Yi,Ys|Xi,Xs) = 0. (for all s ≠ i).

4. The disturbance ɛ and explanatory variable X are

uncorrelated. cov(ɛi,Xi) = 0.

cov(ɛi,Xi) = E[ɛi−E(ɛi)][Xi−E(Xi)]

= E[ɛi(Xi−E(Xi))]

= E(ɛiXi)−E(Xi)E(ɛi) = E(ɛiXi) = 0

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 2 - 24

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-37-2048.jpg)

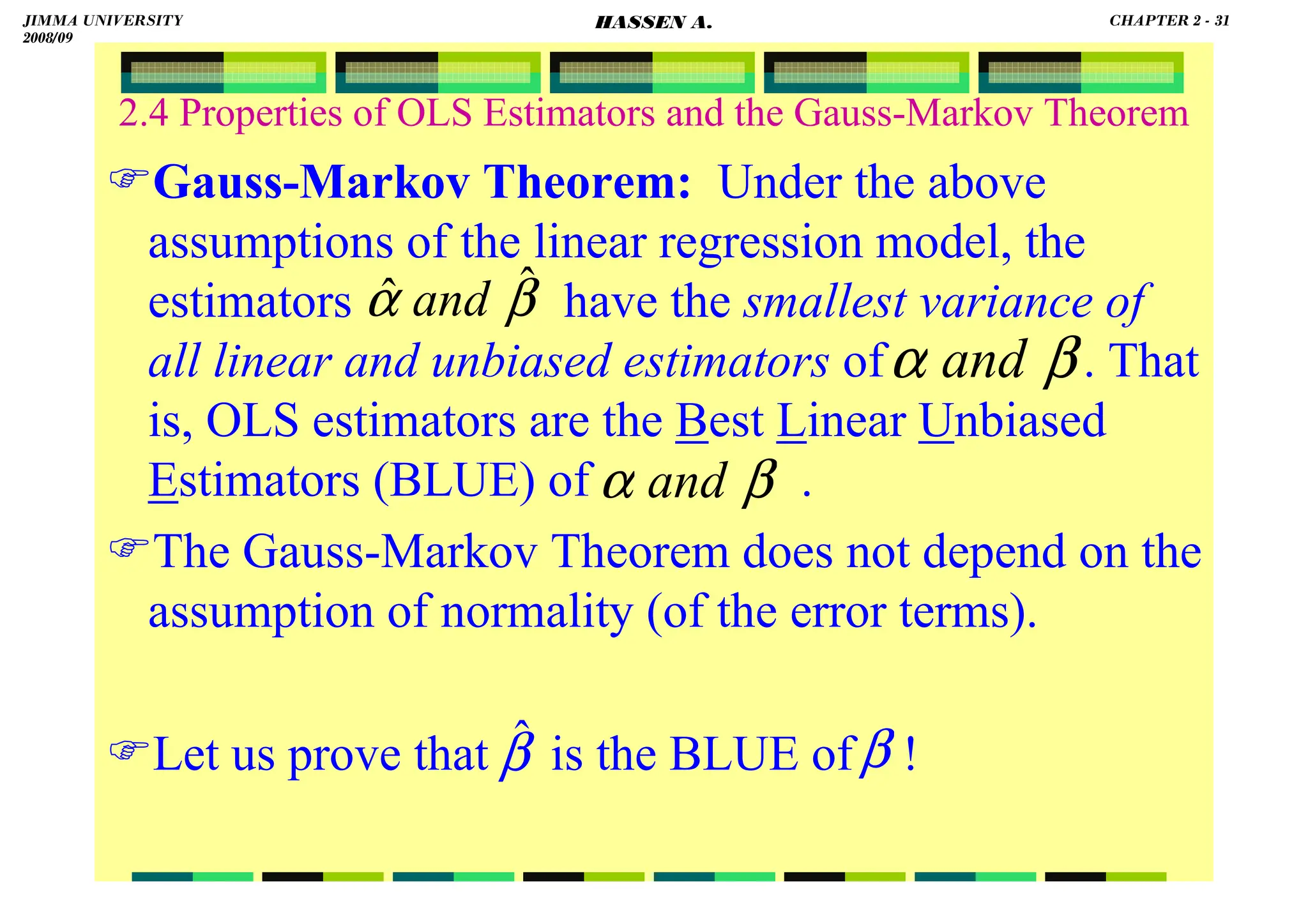

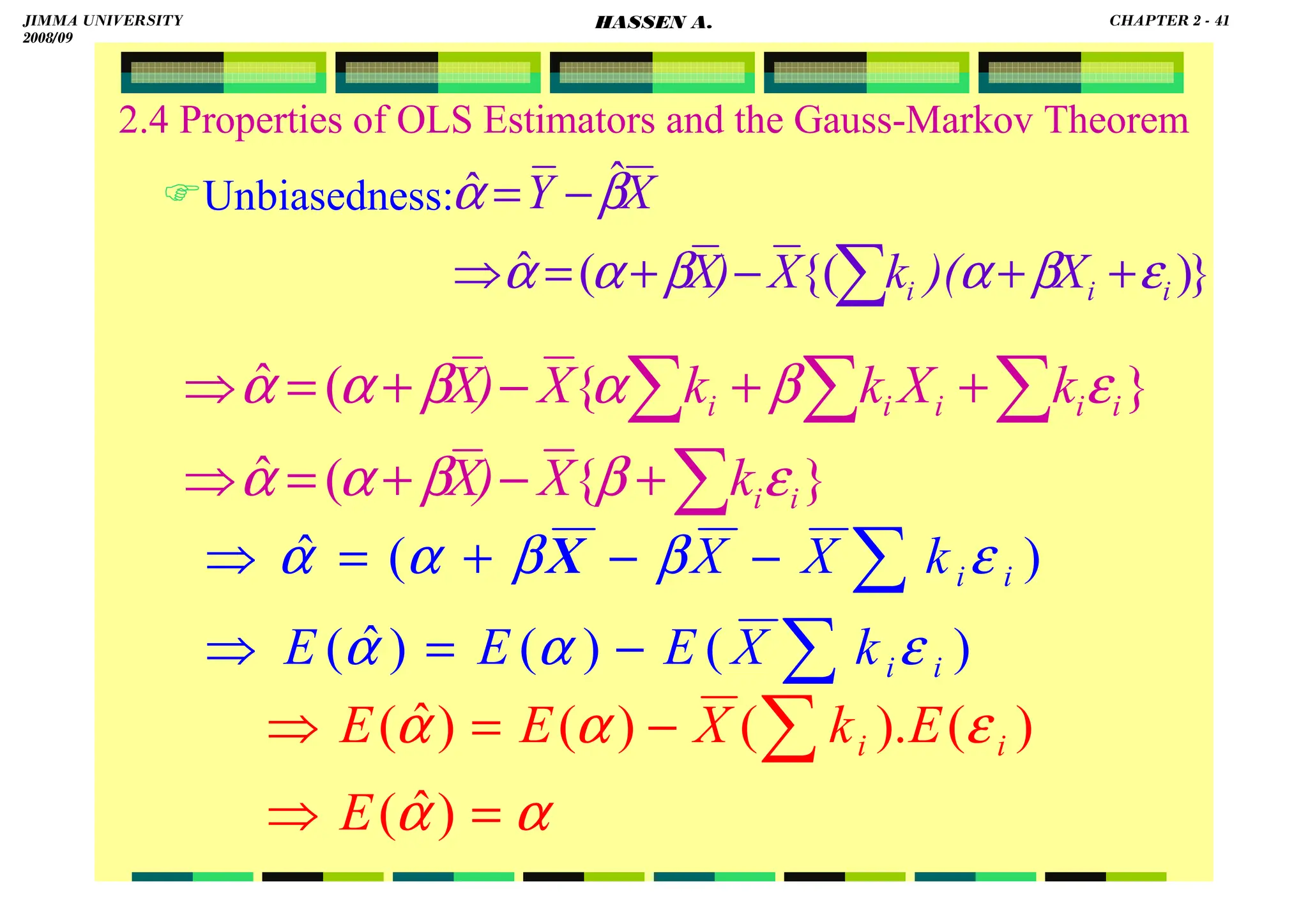

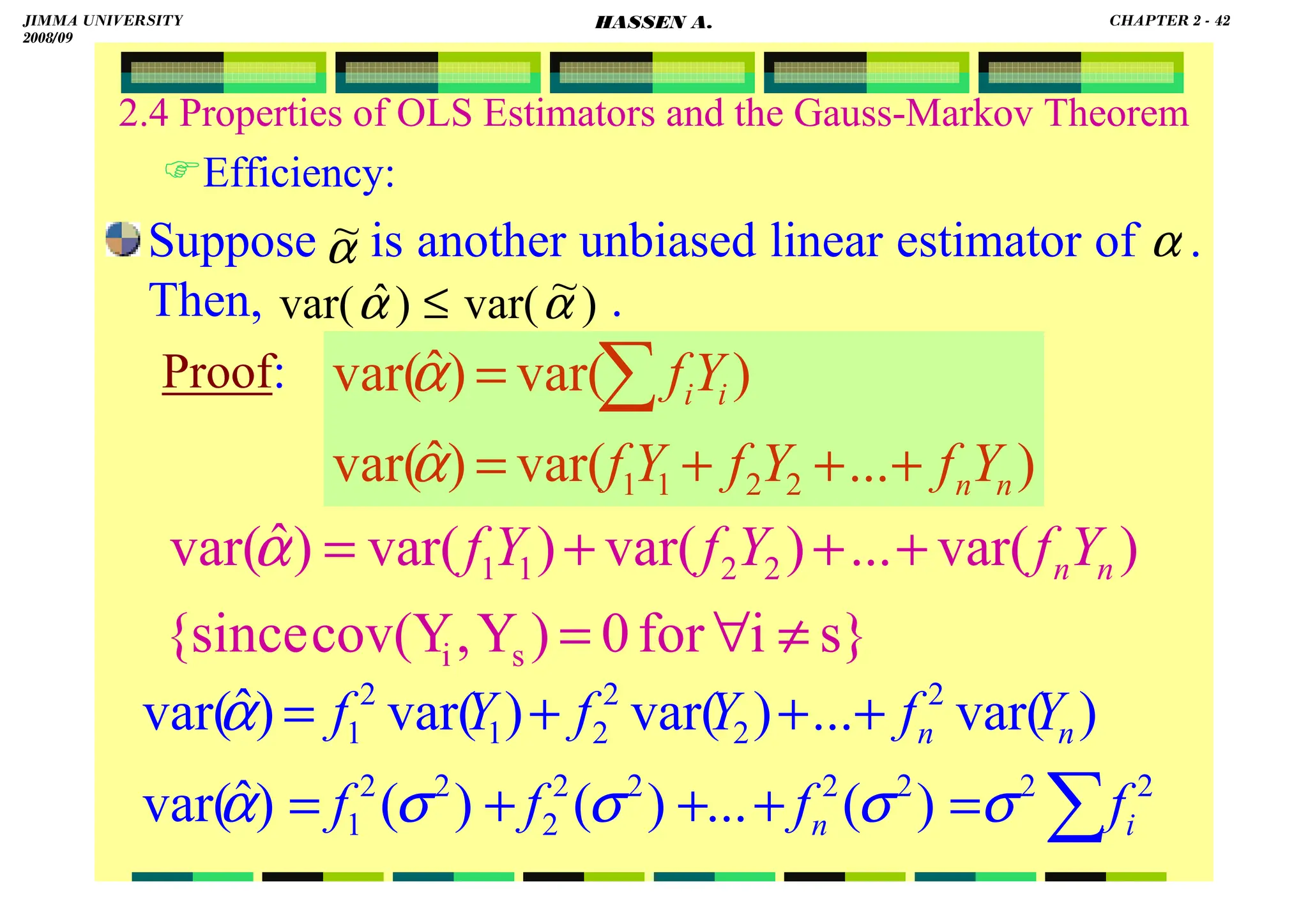

![HASSEN ABDA

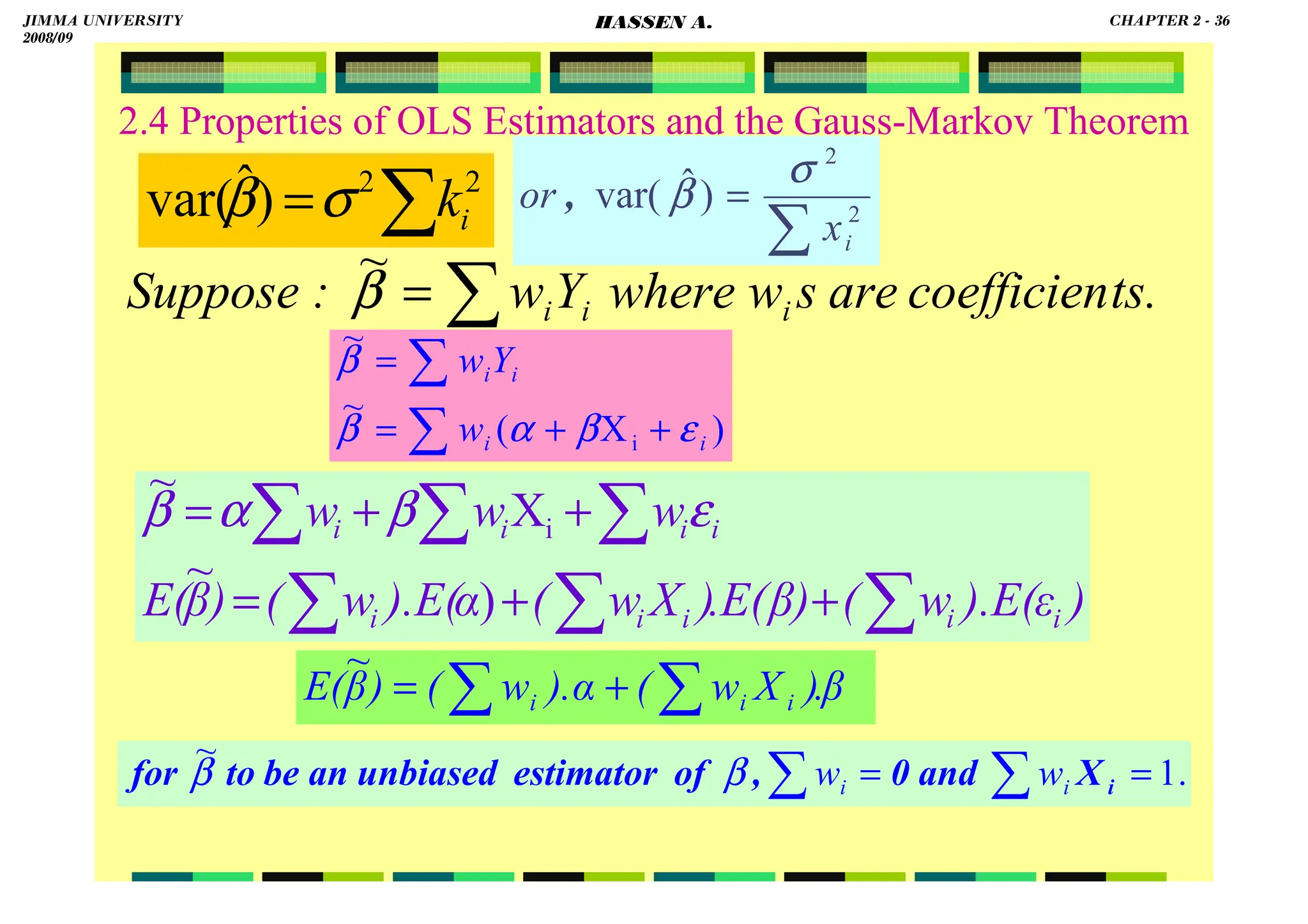

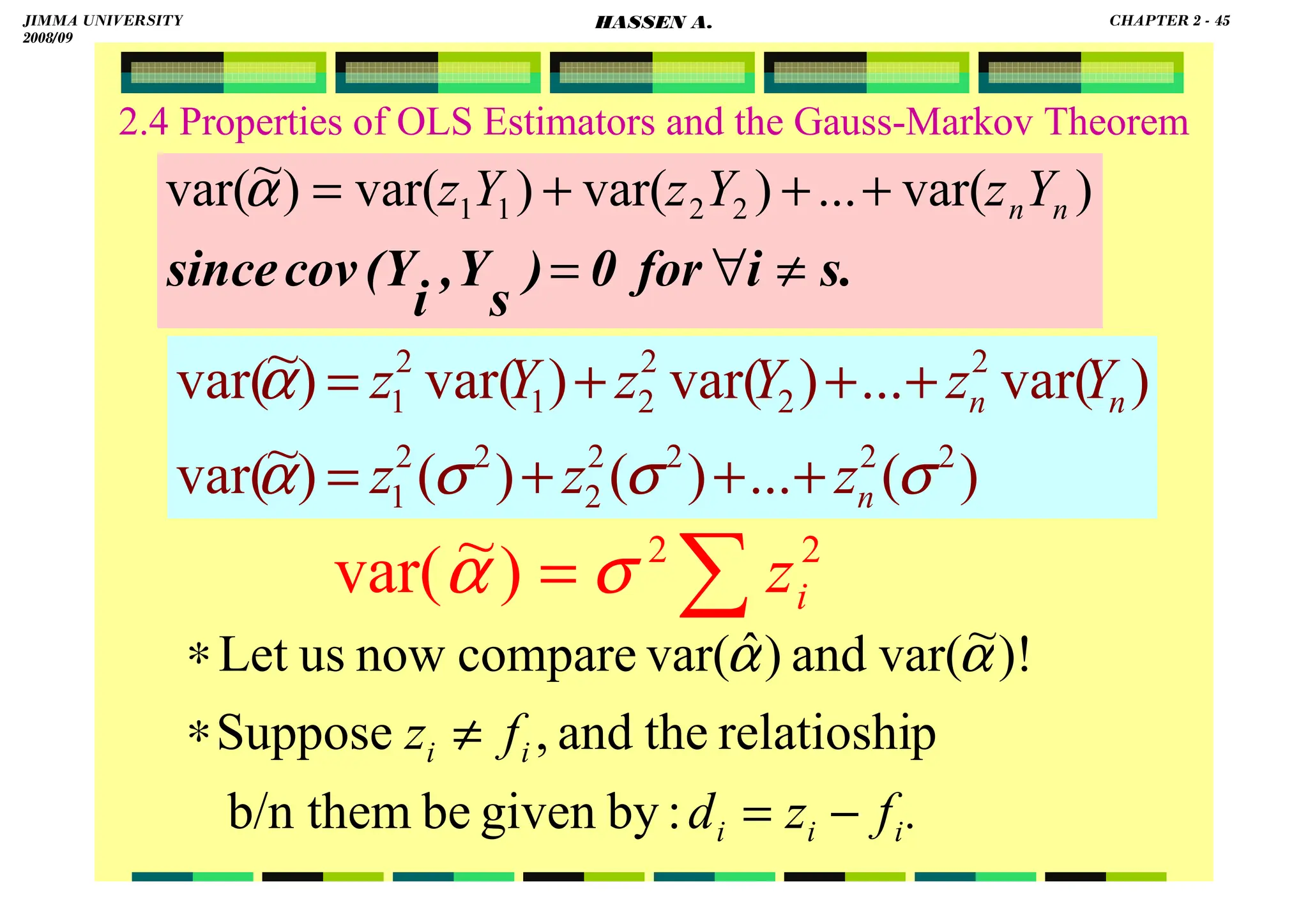

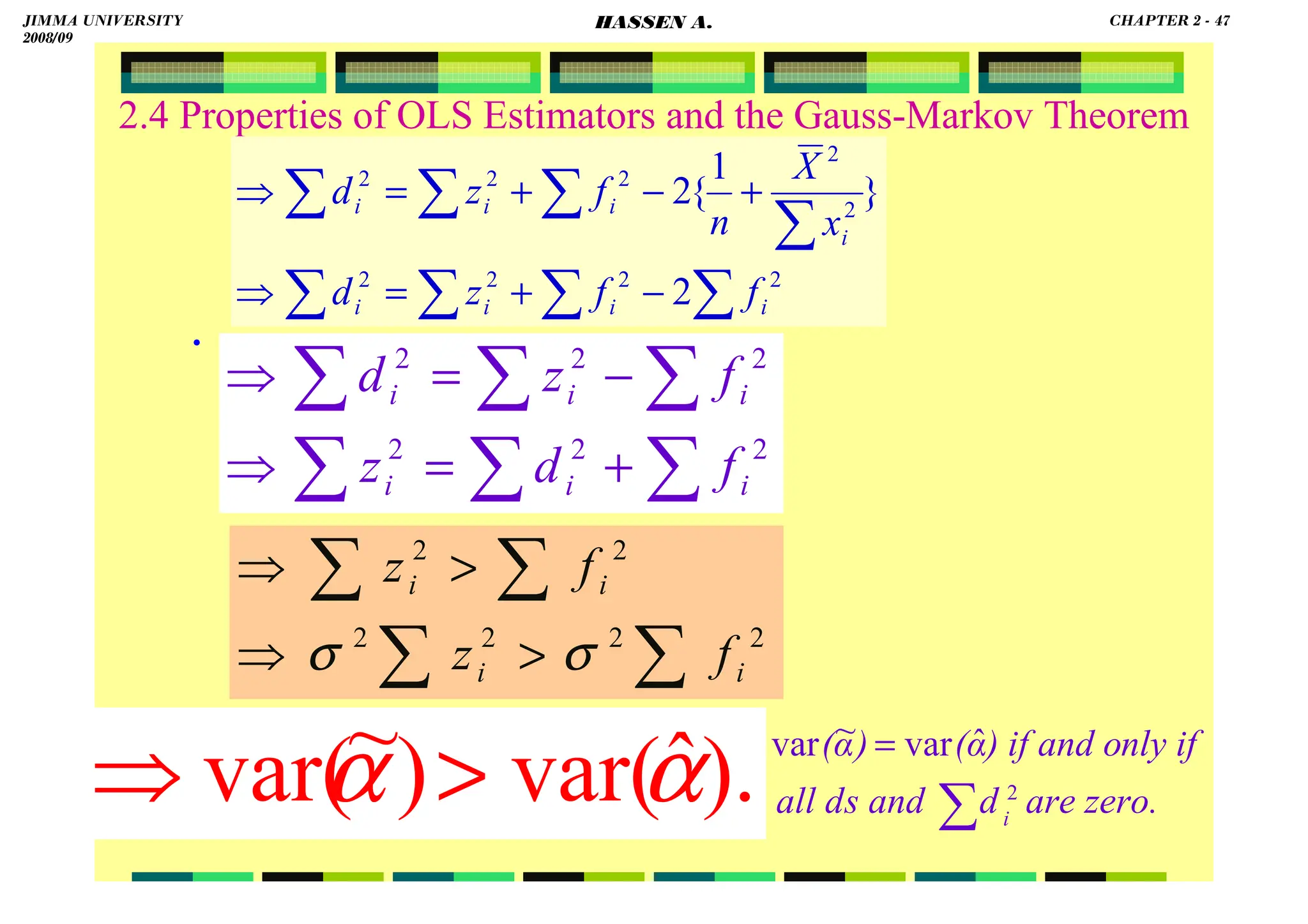

2.4 Properties of OLS Estimators and the Gauss-Markov Theorem

Note that:

(1) is a constant

(2)because xi is non-stochastic, ki is also nonstochastic

(3).

(4).

(5).

(6).

0

)

( 2

2

=

=

=

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

i

i

i

i

i

x

x

x

x

k

1

)

(

)

( 2

2

2

=

=

=

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

x

x

x

x

x

x

k

.

1

)

(

)]

[( 2

2

2

2

2

2

2

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑ =

=

=

i

i

i

i

i

i

x

x

x

x

x

k

1

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

( 2

2

2

2

2

=

+

=

+

=

=

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

x

x

X

x

x

X

x

x

x

X

x

x

X

k

∑ 2

i

x

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 2 - 33

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-46-2048.jpg)

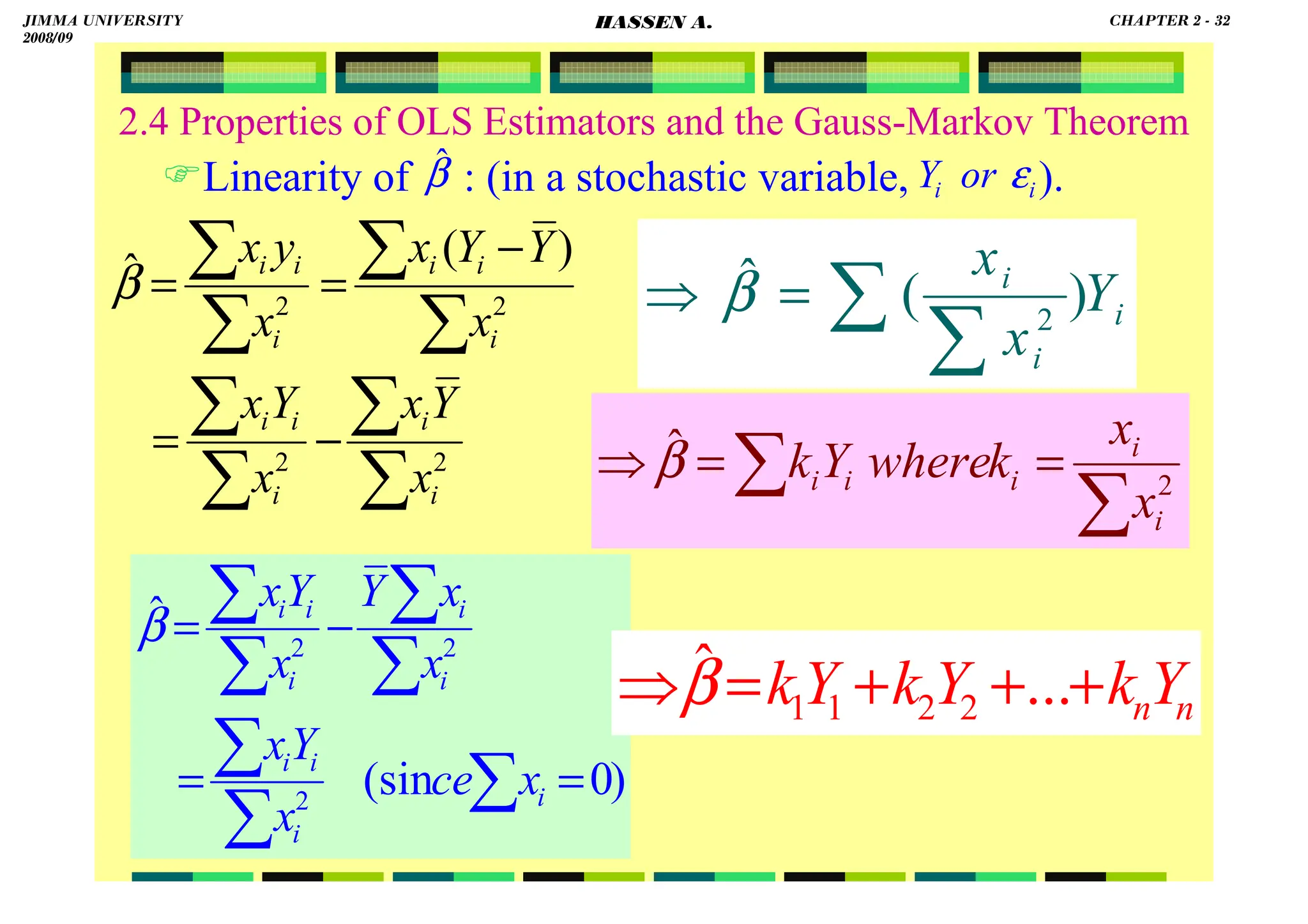

![HASSEN ABDA

2.4 Properties of OLS Estimators and the Gauss-Markov Theorem

Unbiasedness:

)

ˆ

ˆ

i

i

i

i

i

X

(

k

Y

k

ε

β

α

β

β

+

+

=

=

∑

∑

]

1

X

0

[

ˆ

X

ˆ

i

i

=

=

+

=

+

+

=

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

k

and

k

because

k

k

k

k

ε

β

β

ε

β

α

β

)

(

).

(

)

(

)

ˆ

(

)

...

(

)

(

)

ˆ

( 2

2

1

1

i

i

n

n

E

k

E

E

k

k

k

E

E

E

ε

β

β

ε

ε

ε

β

β

∑

+

=

+

+

+

+

=

β

β

β

β

=

+

= ∑

)

ˆ

(

)

0

).(

(

)

ˆ

(

E

k

E i

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 2 - 34

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-47-2048.jpg)

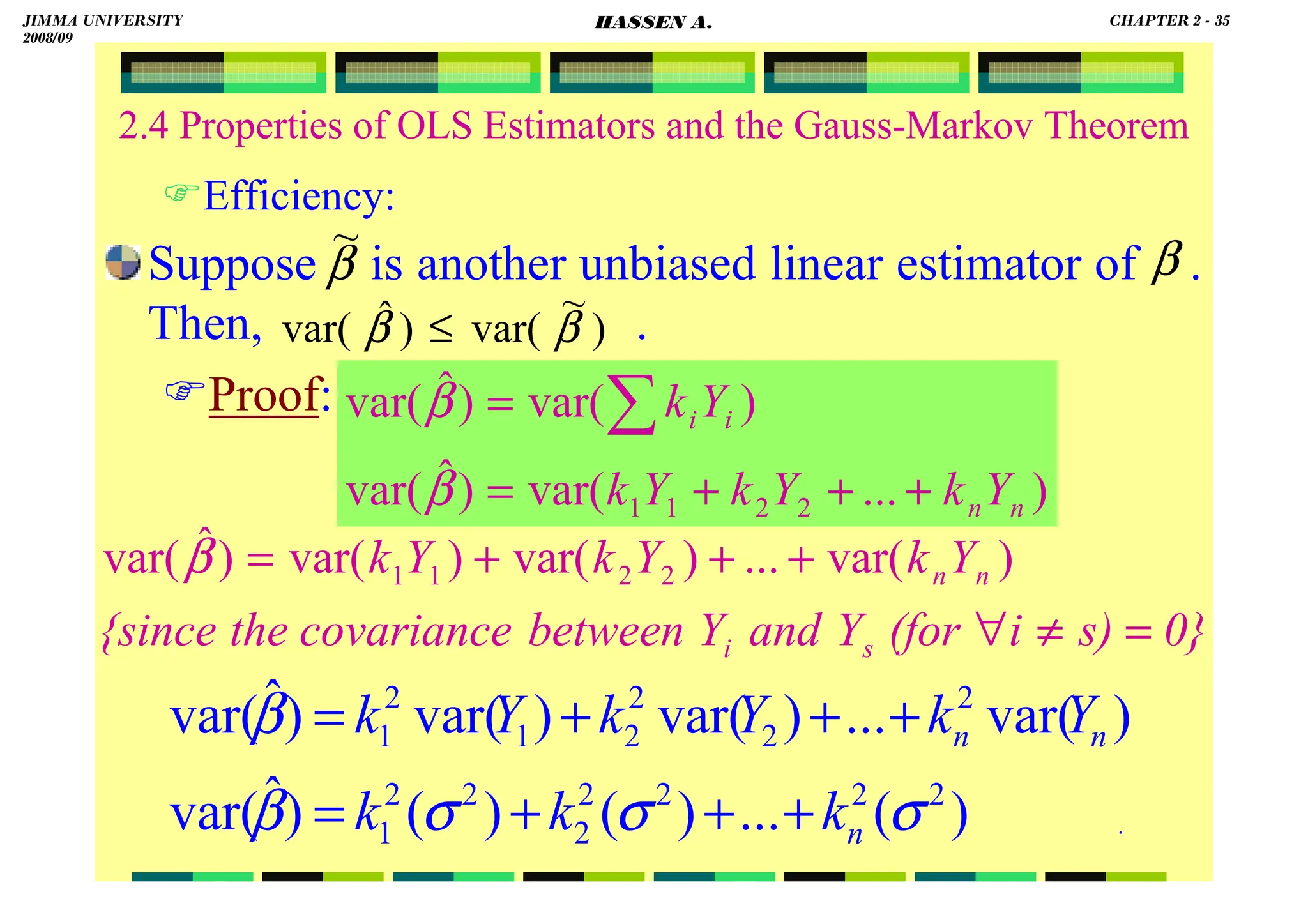

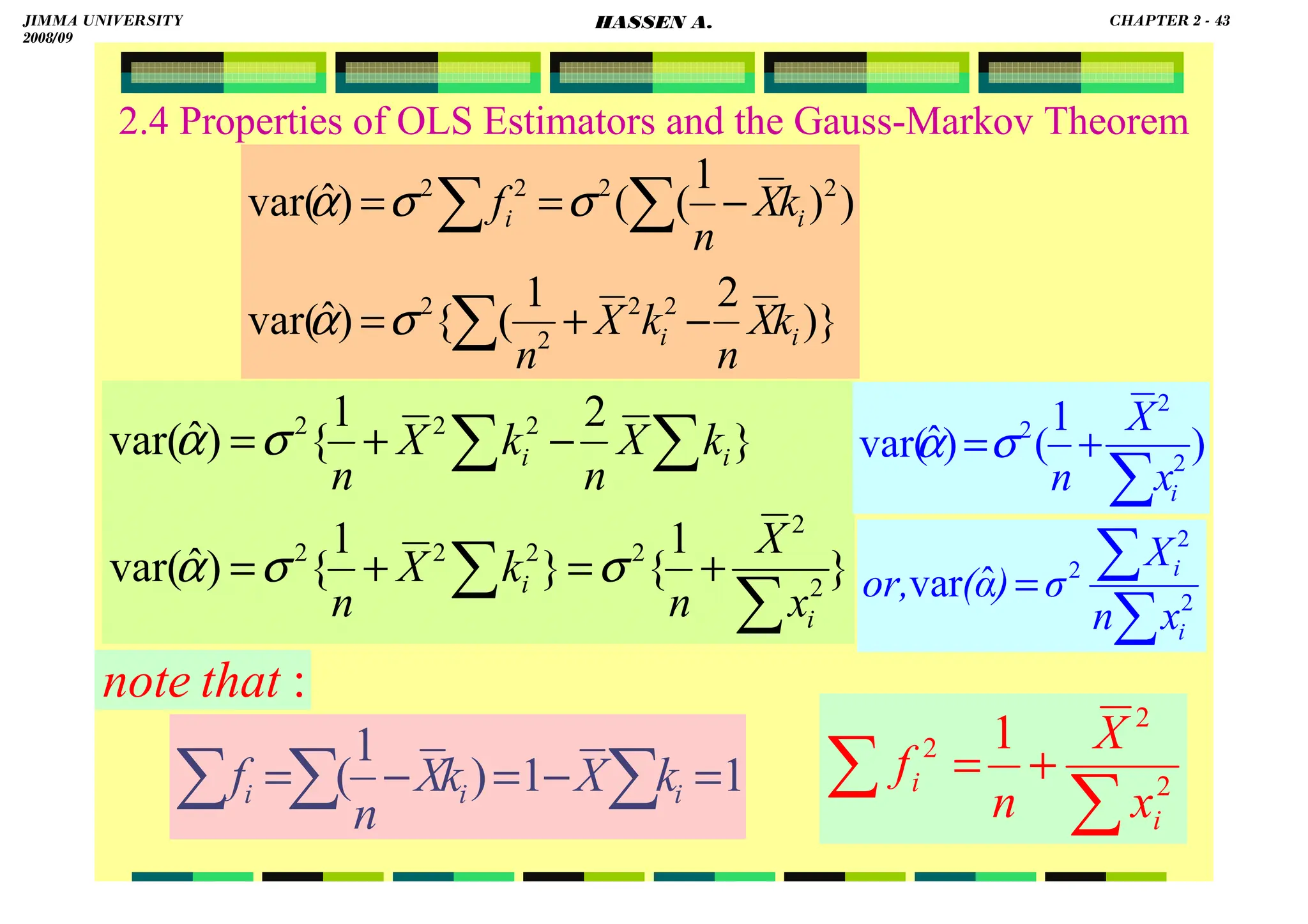

![HASSEN ABDA

2.4 Properties of OLS Estimators and the Gauss-Markov Theorem

.

X

X

z

X

X

z

X

z

X

z

X

X

z

x

z

z

X

z

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

−

=

−

=

−

=

−

=

−

=

⇒

=

=

∗

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

)

1

(

0

)

(

,

1

and

0,

Because

)}

)(

(

1

{

2

)}

)(

(

1

{

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

X

x

X

n

f

z

d

x

z

x

X

z

n

f

z

d

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

−

−

−

+

=

⇒

−

−

+

=

⇒

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

}

{

2

2

2

2

∑

∑

∑

∑ −

+

= i

i

i

i

i f

z

f

z

d )

(

1

2

∑

−

=

i

i

i

x

x

X

n

f

where

]}

)

1

(

[

{

2 2

2

2

2

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑ −

−

+

=

i

i

i

i

i

i

x

x

X

n

z

f

z

d

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 2 - 46

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-59-2048.jpg)

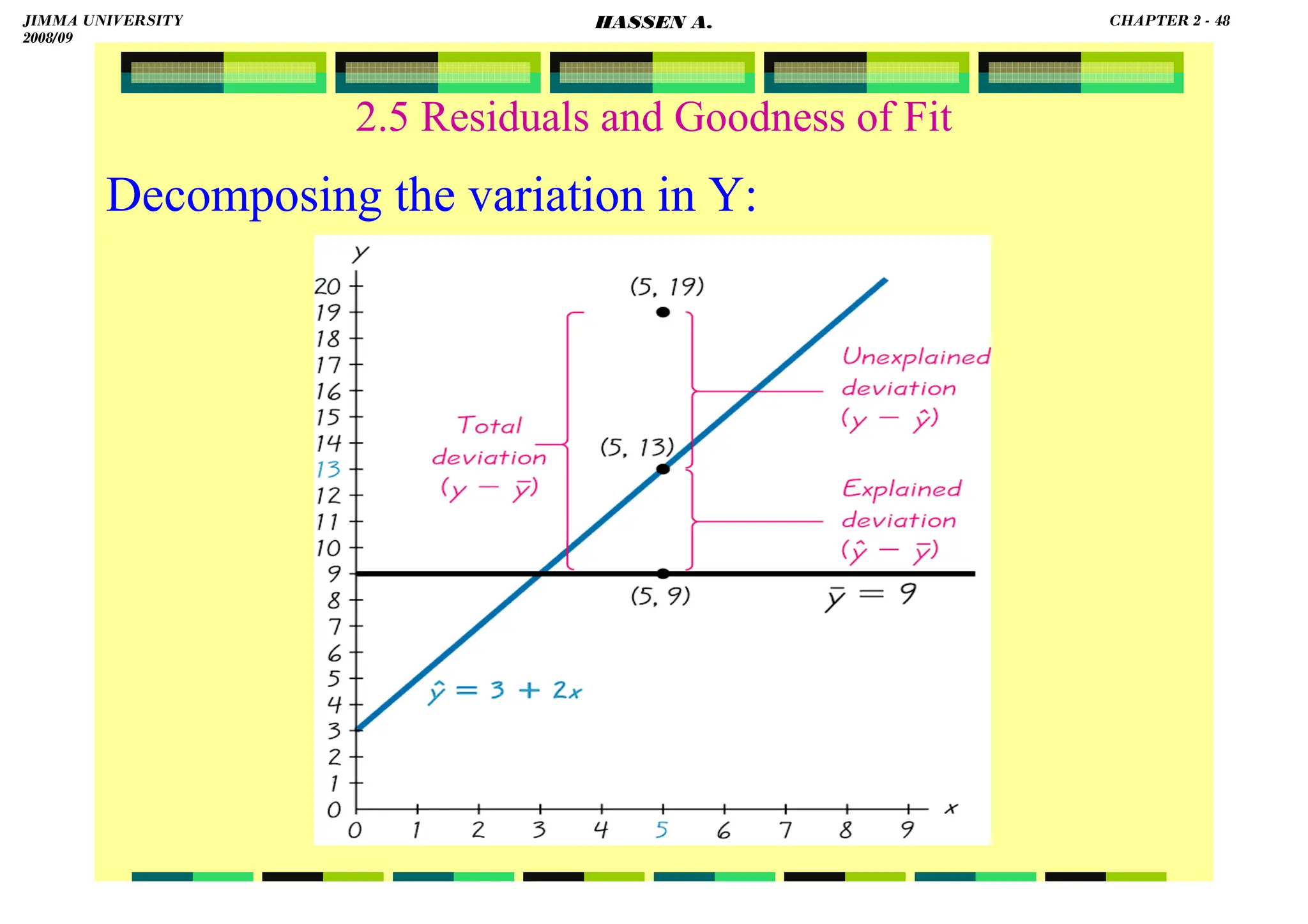

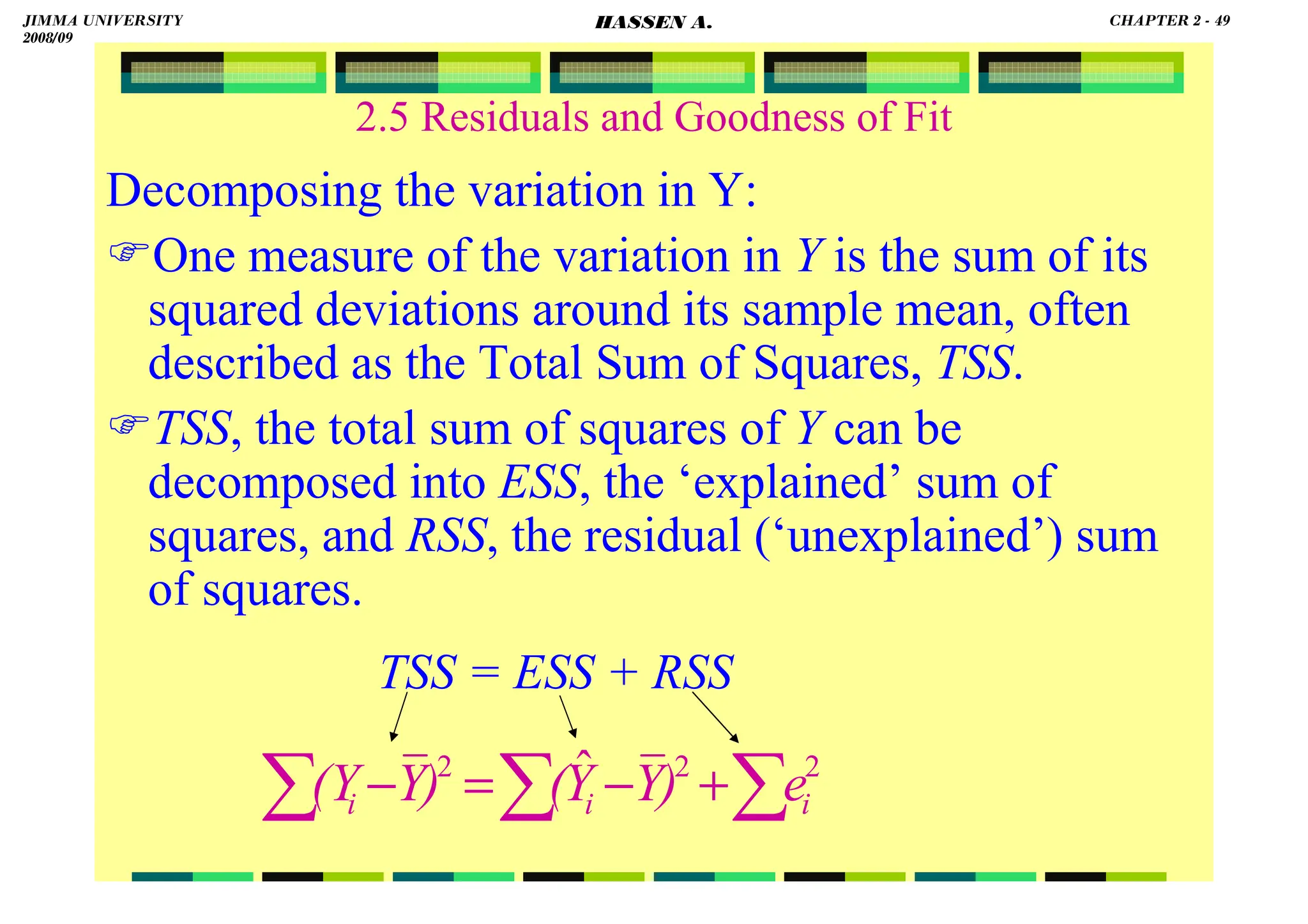

![HASSEN ABDA

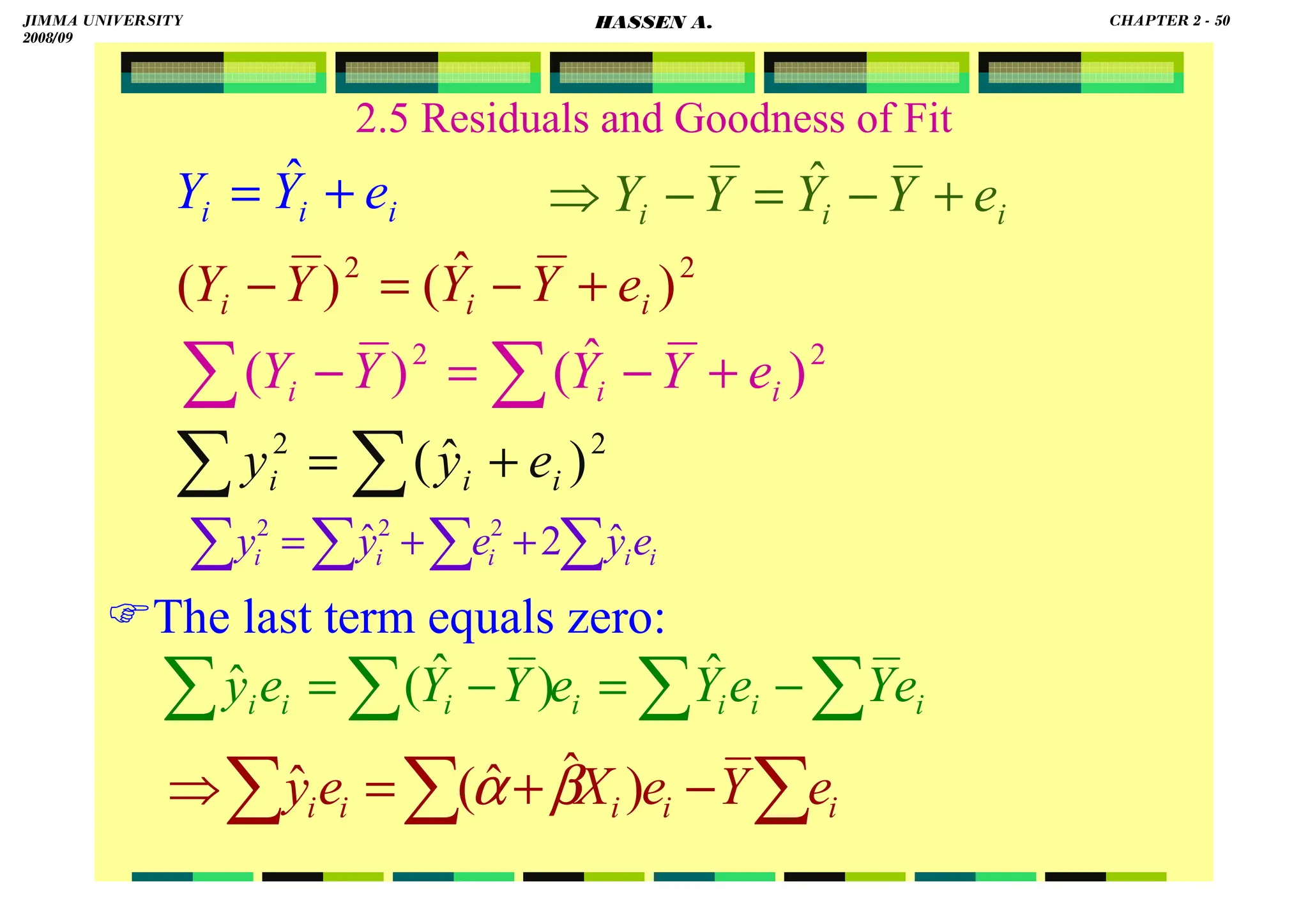

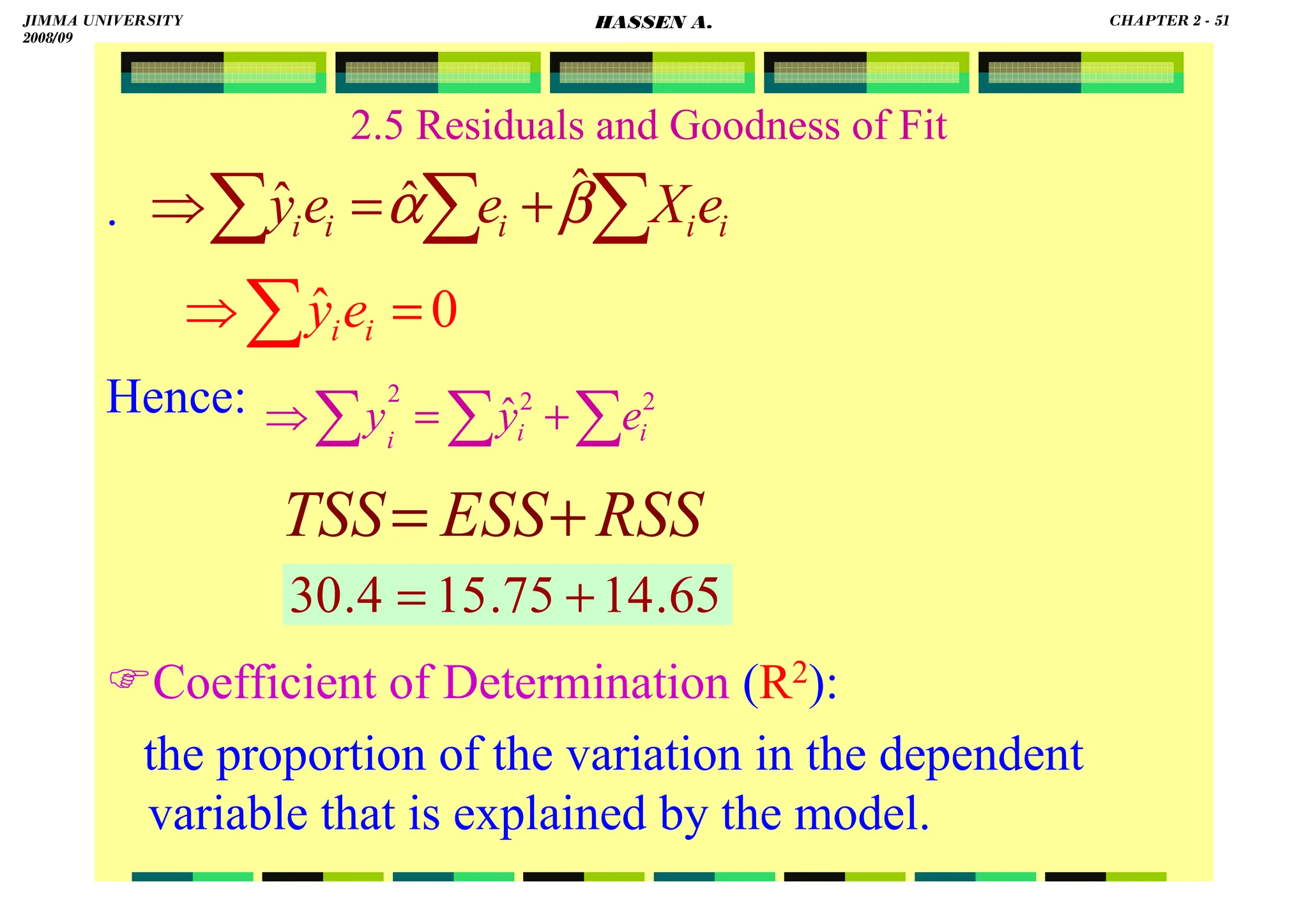

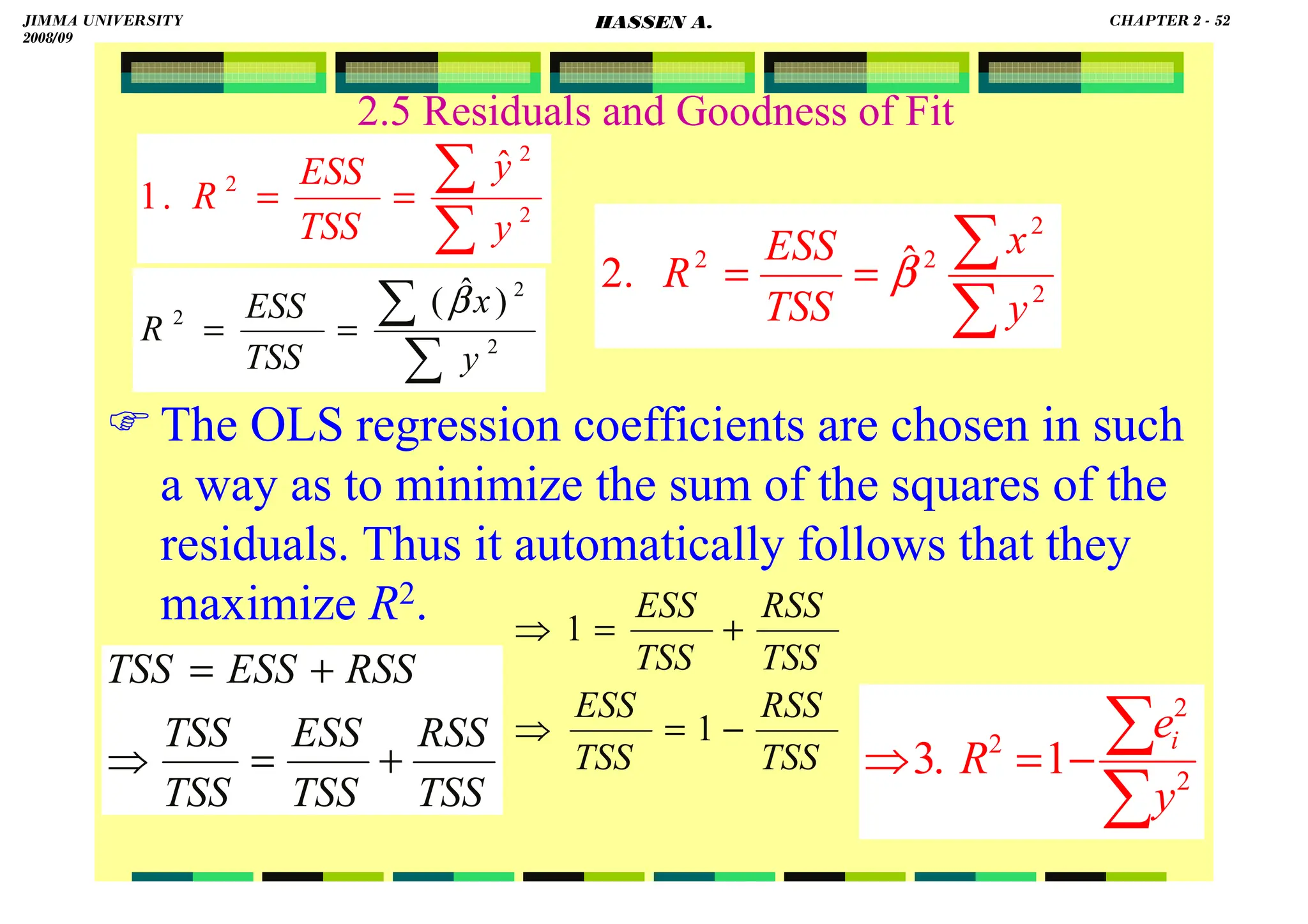

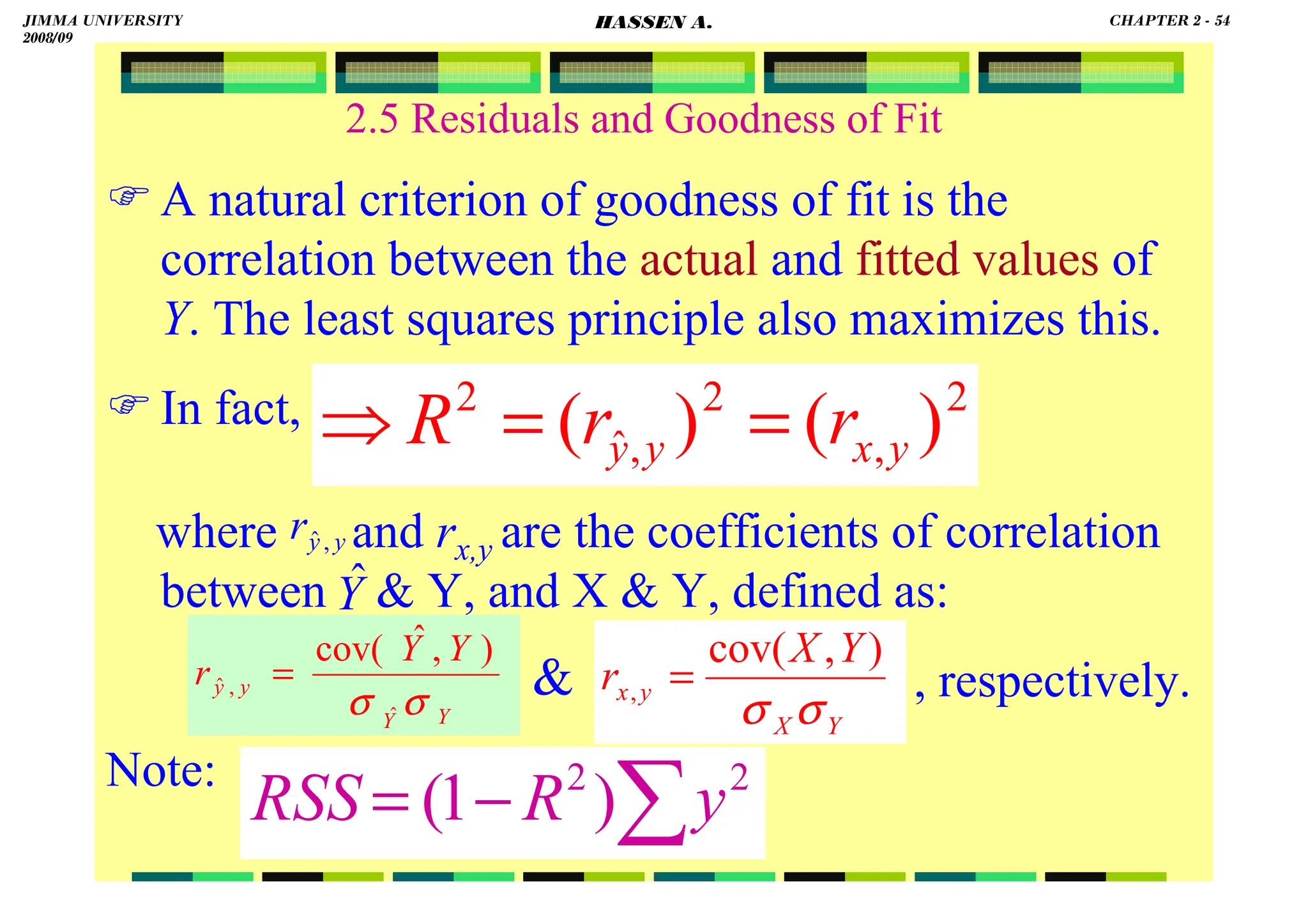

2.5 Residuals and Goodness of Fit

Coefficient of Determination (R2):

∑

∑

∑

∑

= 2

2

2

y

xy

x

xy

R

∑ ∑

∑

=

⇒ 2

2

2

2

)

(

.

5

y

x

xy

R

)

)(

(

ˆ

2

2

2

2

∑

∑

∑

∑

=

=

y

x

x

xy

TSS

ESS

R β

∑

∑

=

= 2

2 ˆ

.

4

y

xy

TSS

ESS

R β

)

var(

)

var(

)]

,

[cov(

.

6

2

2

Y

X

Y

X

R

×

=

⇒

5181

.

0

4

.

30

75

.

15

ˆ

2

2

2

=

=

=

=

∑

∑

y

y

TSS

ESS

R

i

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 2 - 53

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-66-2048.jpg)

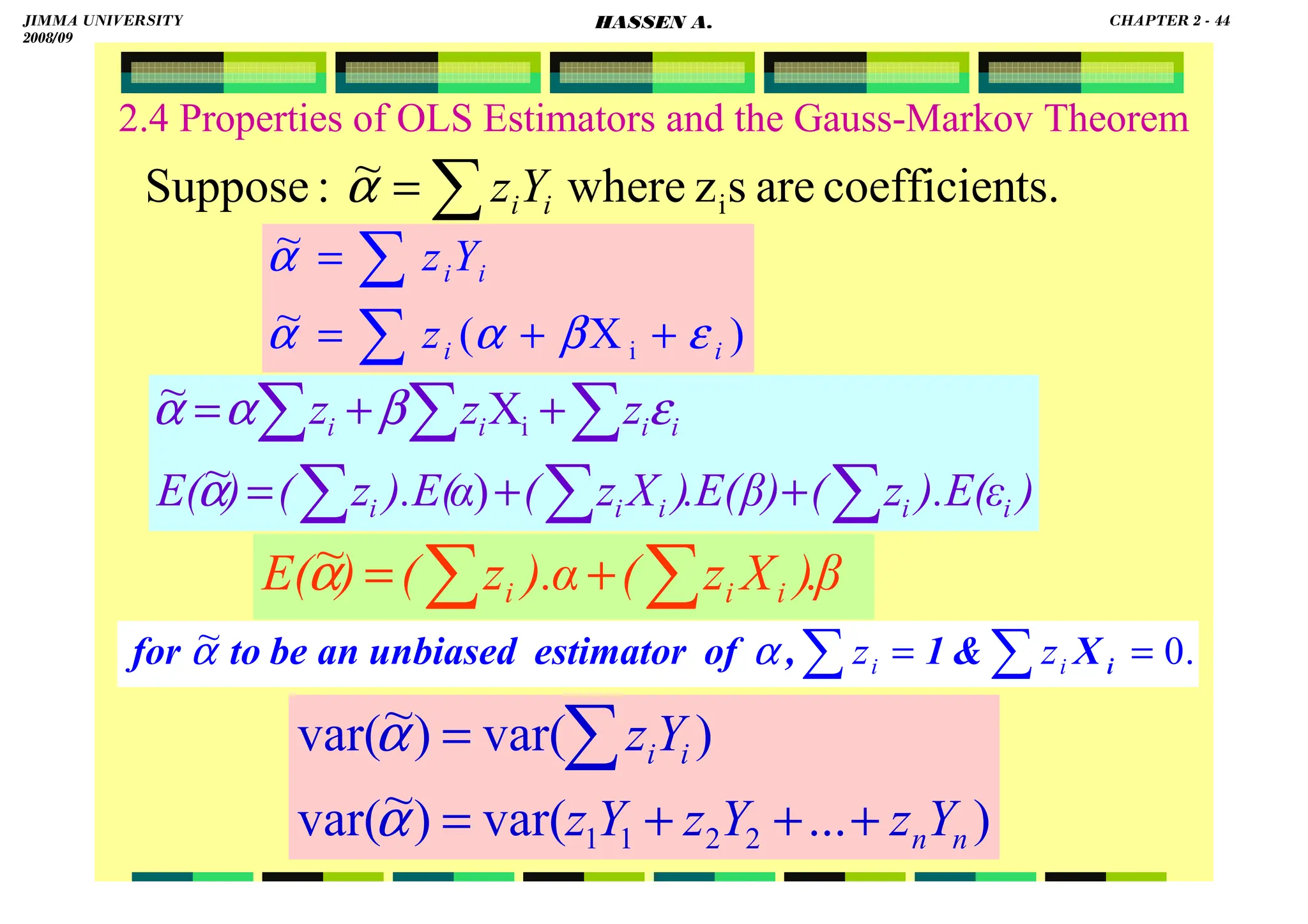

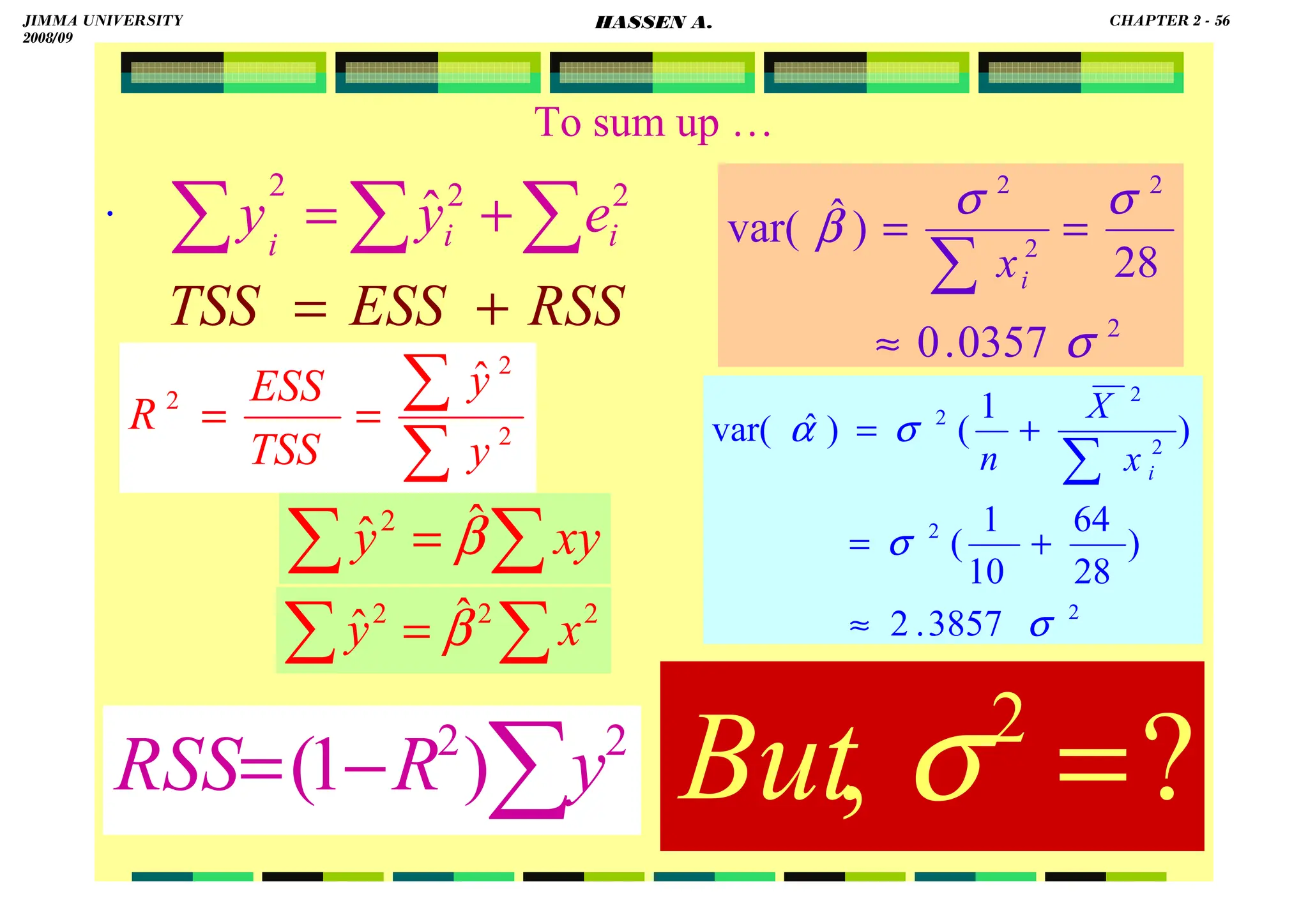

![HASSEN ABDA

55

To sum up:

Use

OLS:

Given the assumptions of the linear regression

model, the estimators have the smallest

variance of all linear and unbiased estimators of

.

i

i X

X

Y

E

estimate

to

i

X

i

Y β

α

β

α +

=

+

= ]

|

[

ˆ

ˆ

ˆ

∑ ∑ −

−

=

−

=

= =

=

∑

n

i

n

i

i

i

i

i

n

i

i )

X

β

α

(Y

)

Y

(Y

e

1 1

2

2

1

2 ˆ

ˆ

ˆ

β̂

,

α̂

min

∑

∑

= 2

ˆ

x

xy

β X

β

Y

α ˆ

ˆ −

=

β

α ˆ

ˆ and

β

α and

∑

= 2

2

)

ˆ

var(

i

x

σ

β )

1

(

)

ˆ

var( 2

2

2

∑

+

=

i

x

X

n

σ

α

∑

∑

= 2

2

2

i

i

x

n

X

σ

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 2 - 55

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-68-2048.jpg)

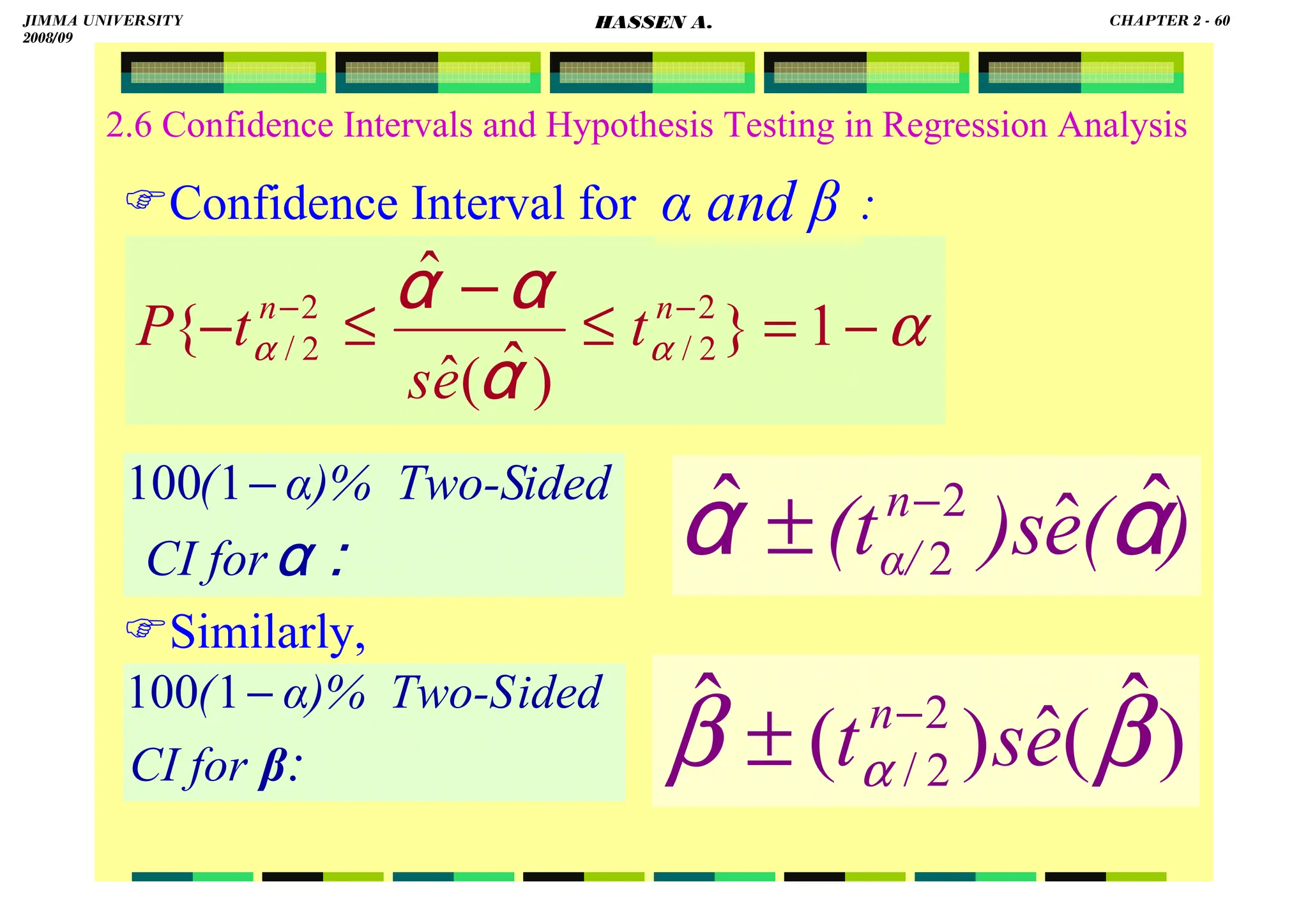

![HASSEN ABDA

2.6 Confidence Intervals and Hypothesis Testing in Regression Analysis

CI for (continued):

OR

:

r σ

ided CI fo

α)% Two-S

( 2

1

100 −

⇒

2

σ

α

χ

σ

σ

χ

σ

α

α

−

=

−

≤

≤

−

⇒

−

−

−

1

}

ˆ

)

2

(

ˆ

)

2

(

{ 2

2

);

2

/

(

1

2

2

2

2

);

2

/

(

2

n

n

n

n

P

]

ˆ

)

2

(

,

ˆ

)

2

(

[ 2

2

);

2

/

(

1

2

2

2

);

2

/

(

2

−

−

−

−

−

n

n

n

n

α

α χ

σ

χ

σ

]

,

[ 2

2

);

2

/

(

1

2

2

);

2

/

( −

−

− n

n

RSS

RSS

α

α χ

χ

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 2 - 62

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-75-2048.jpg)

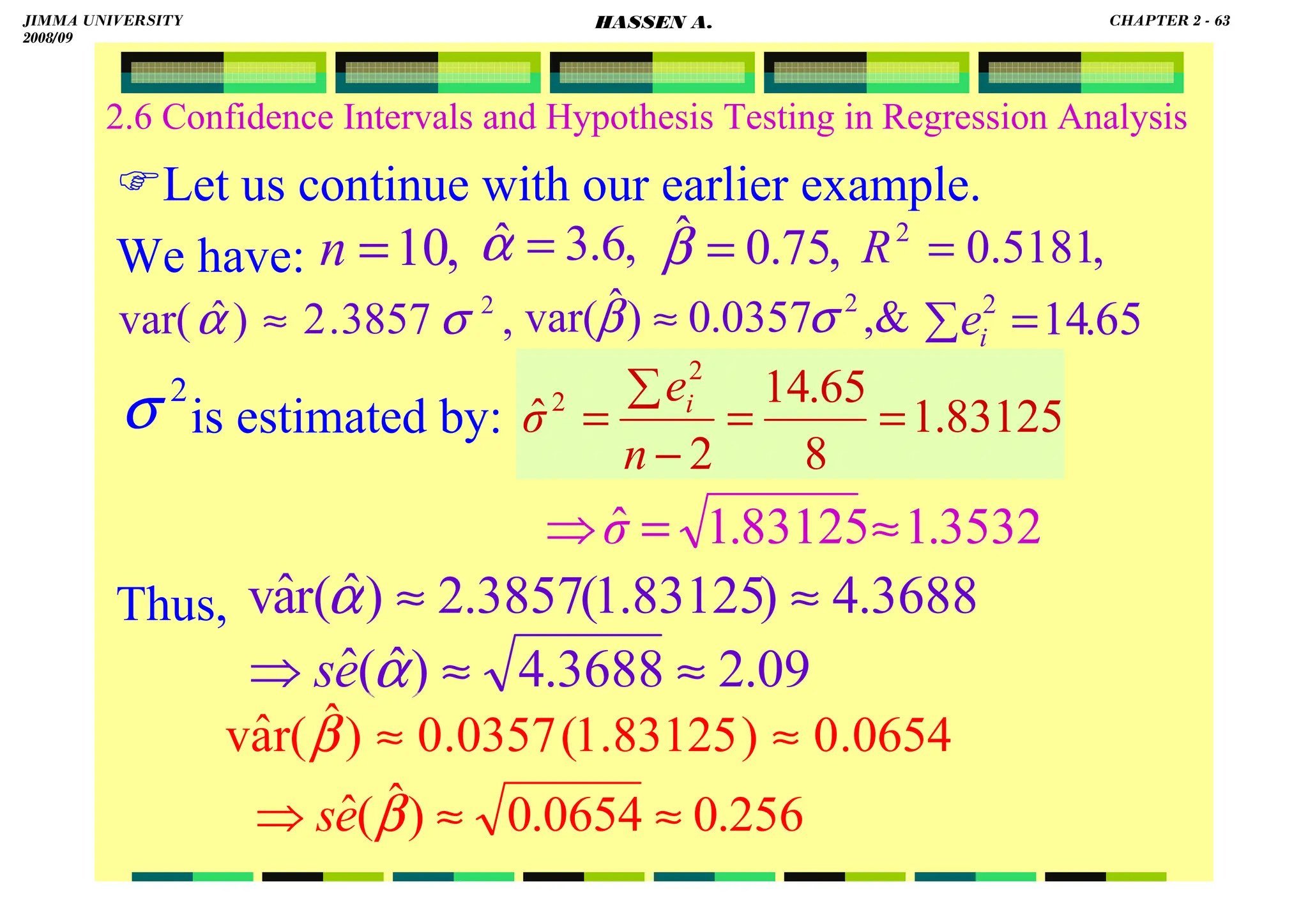

![HASSEN ABDA

2.6 Confidence Intervals and Hypothesis Testing in Regression Analysis

95% CI for :

8195

.

4

6

3 ±

= .

::::

αααα

for

CI

%

95

::::

β

for

CI

%

95

α and β

05

.

0

95

.

0

1 =

⇒

=

− α

α

)

09

.

2

(

306

.

2

)

09

.

2

(

6

3

6

3 8

025

.

0

)

(

)

(t

.

.

±

=

±

:

α

for

CI

95%

⇒

)

256

.

0

(

306

.

2

)

256

.

0

(

75

.

0

75

.

0 8

025

.

0

)

(

)

(t

±

=

±

5903

.

0

75

.

0 ±

=

:

for

CI

95% β

⇒

025

.

0

2

/ =

⇒α

8.4195]

1.2195,

[−

1.3403]

[0.1597,

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 2 - 64

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-77-2048.jpg)

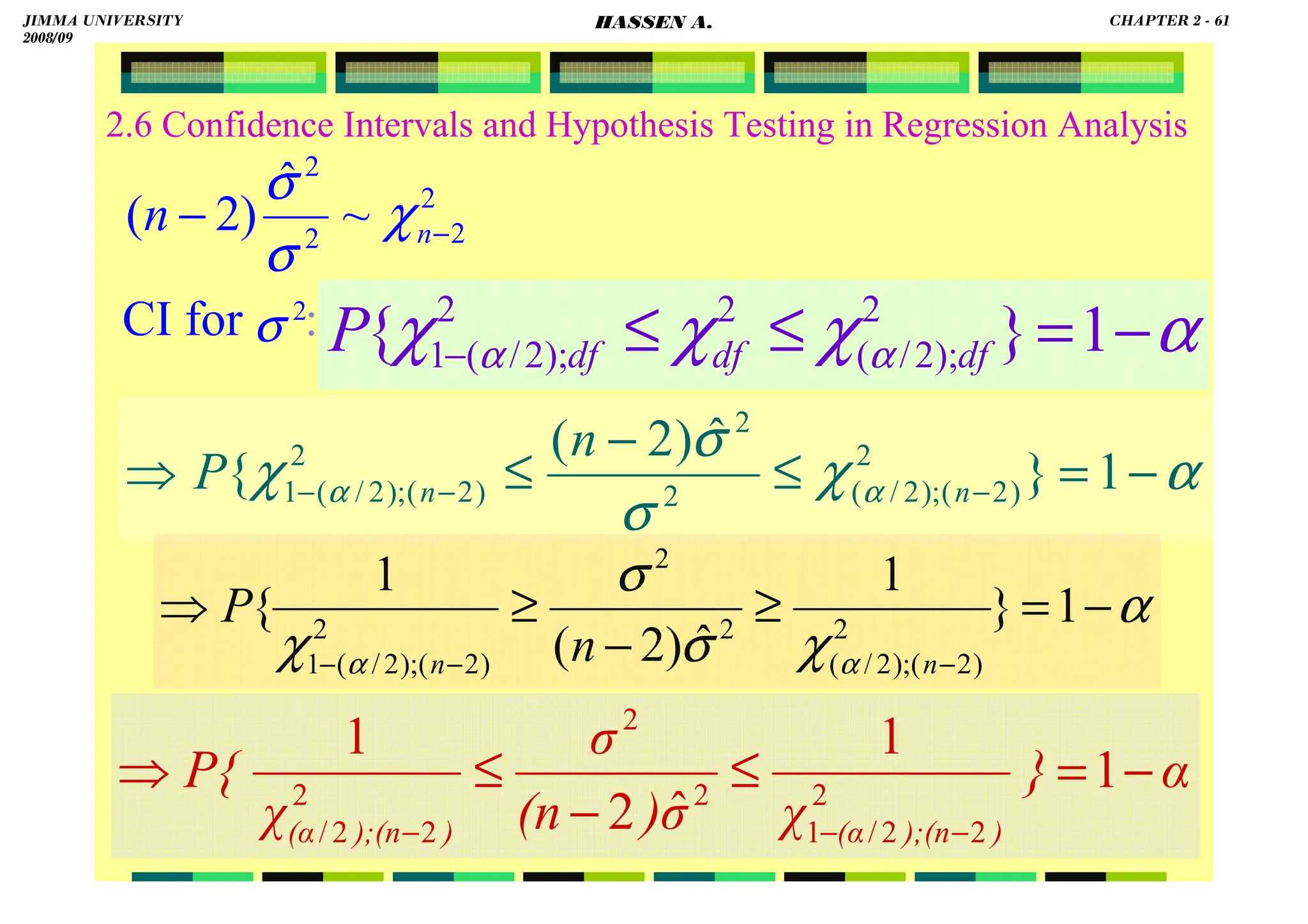

![HASSEN ABDA

2.6 Confidence Intervals and Hypothesis Testing in Regression Analysis

95% CI for :

::::

2

σ

for

CI

%

95

⇒

2

σ

83125

.

1

ˆ 2

=

σ

6.72]

[0.84,

=

:

2

2

;

2

/ −

n

α

χ 5

.

17

2

8

;

025

.

0 =

χ

18

.

2

2

8

;

975

.

0 =

χ

:

2

2

);

2

/

(

1 −

− n

α

χ

]

ˆ

)

2

(

,

ˆ

)

2

(

[ 2

2

);

2

/

(

1

2

2

2

);

2

/

(

2

−

−

−

−

−

n

n

n

n

α

α χ

σ

χ

σ

]

18

.

2

65

.

14

,

5

.

17

65

.

14

[

=

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 2 - 65

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-78-2048.jpg)

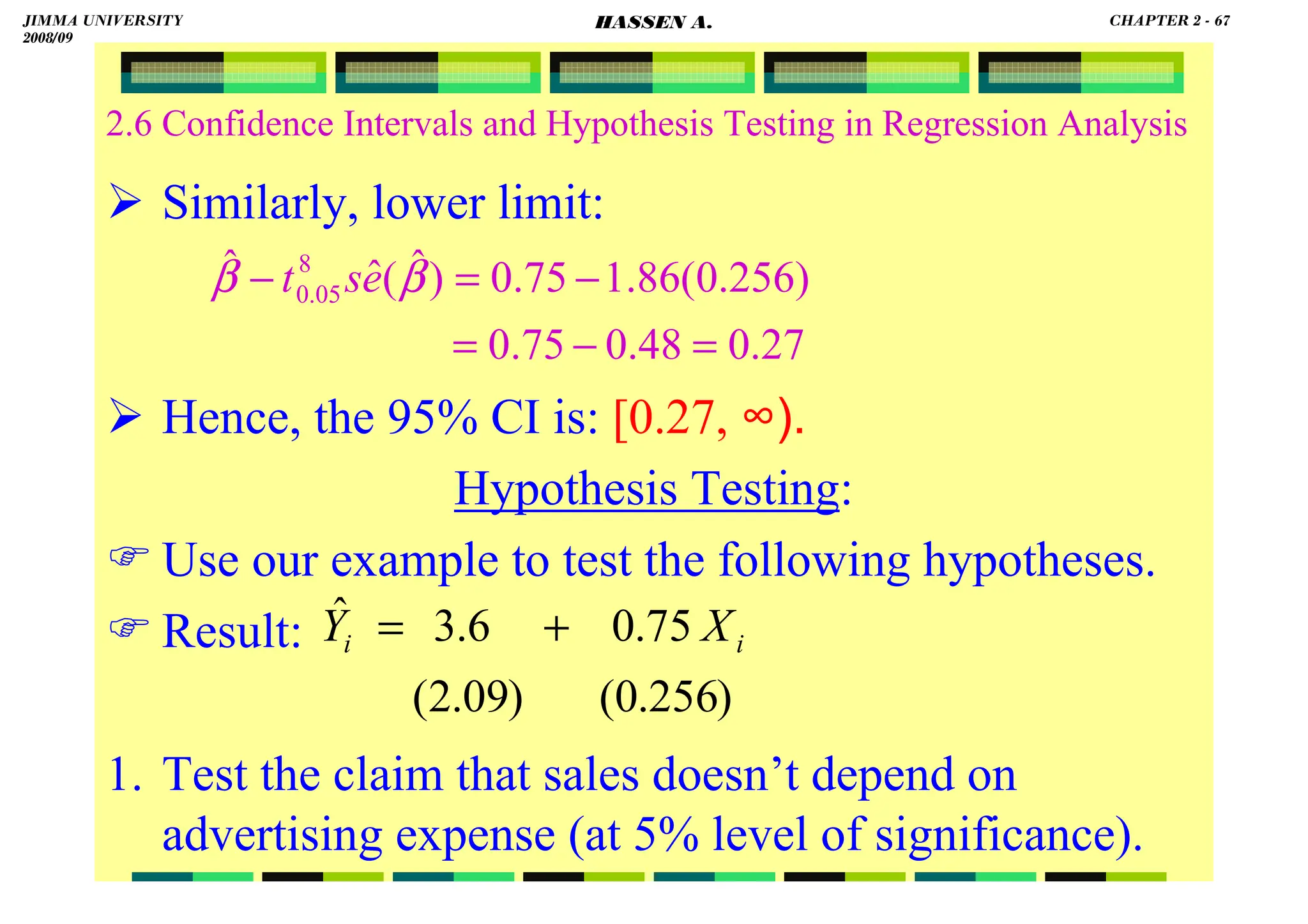

![HASSEN ABDA

2.6 Confidence Intervals and Hypothesis Testing in Regression Analysis

The confidence intervals we have constructed for

are two-sided intervals.

Sometimes we want either the upper or lower limit

only, in which case we construct one-sided intervals.

For instance, let us construct a one-sided (upper

limit) 95% confidence interval for .

Form the t-table, .

Hence,

The confidence interval is (- ∞, 1.23].

2

, σ

β

α

β

86

.

1

8

05

.

0 =

t

23

.

1

48

.

0

75

.

0

)

256

.

0

(

86

.

1

75

.

0

)

ˆ

(

ˆ

.

ˆ 8

05

.

0

=

+

=

+

=

+ β

β e

s

t

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 2 - 66

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-79-2048.jpg)

![HASSEN ABDA

2.7 Prediction with the Simple Linear Regression

The variance of the prediction error is:

Thus, the variance increases the farther away the

value of X0 is from , the mean of the observations

on the basis of which have been computed.

)

var(

)

ˆ

,

ˆ

cov(

2

)

ˆ

var(

)

ˆ

var(

)

ˆ

var(

0

2

0

P

P

P

X

X

Y

Y

ε

β

β

α

α

β

β

α

α

+

−

−

+

−

+

−

=

−

2

2

2

0

2

2

0

2

2

2

2

2

)

ˆ

var( σ

σ

σ

σ +

−

+

=

−

∑

∑

∑

∑

i

i

i

i

P

P

x

X

X

x

X

x

n

X

Y

Y

]

)

(

1

1

[

)

ˆ

var( 2

2

0

2

∑

−

+

+

=

−

i

P

P

x

X

X

n

Y

Y σ

X

β

α ˆ

ˆ

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 2 - 75

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-88-2048.jpg)

![HASSEN ABDA

2.7 Prediction with the Simple Linear Regression

The variance of the prediction error is:

Again, the variance increases the farther away the

value of X0 is from .

The variance (the standard error) of the prediction

error is smaller in this case (of predicting the

average value of Y, given X) than that of predicting

a value of Y, given X.

)

ˆ

,

ˆ

cov(

2

)

ˆ

var(

)

ˆ

var(

)

ˆ

var( 0

2

0 β

β

α

α

β

β

α

α −

−

+

−

+

−

=

− X

X

Y

Y P

P

]

)

(

1

[

)

ˆ

var( 2

2

0

2

∑

−

+

=

−

⇒

i

P

P

x

X

X

n

Y

Y σ

X

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 2 - 77

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-90-2048.jpg)

![HASSEN ABDA

78

2.7 Prediction with the Simple Linear Regression

Predict (a) the value of sales, and (b) the average

value of sales, for a firm with an advertising expense

of six hundred Birr.

a. From , at Xi = 6,

Point prediction:

[Sales value | advertising of 600 Birr] = 8,100 Birr.

Interval prediction: 95% CI:

]

)

(

1

1

[

ˆ

)

ˆ

(

ˆ 2

2

0

2

*

∑

−

+

+

=

i

P

x

X

X

n

Y

e

s σ

i

i X

Y 75

.

0

6

.

3

ˆ +

=

1

.

8

)

6

(

75

.

0

6

.

3

ˆ =

+

=

i

Y

28

)

8

6

(

10

1

1

35

.

1

)

ˆ

(

ˆ

2

* −

+

+

=

⇒ P

Y

e

s

508

.

1

)

115

.

1

(

35

.

1 =

=

306

.

2

8

025

.

0 =

t

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 2 - 78

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-91-2048.jpg)

![HASSEN ABDA

79

2.7 Prediction with the Simple Linear Regression

Hence,

b. From , at Xi = 6,

Point prediction:

[Average sales | advertising of 600 Birr] = 8,100 Birr.

Interval prediction: 95% CI:

]

)

(

1

[

ˆ

)

ˆ

(

ˆ 2

2

0

2

*

∑

−

+

=

i

P

x

X

X

n

Y

e

s σ

1

.

8

)

6

(

75

.

0

6

.

3

ˆ =

+

=

i

Y

28

)

8

6

(

10

1

35

.

1

)

ˆ

(

2

* −

+

=

⇒ P

Y

se

)

508

.

1

)(

306

.

2

(

1

.

8

%

95 ±

:

CI

]

58

.

11

,

62

.

4

[

i

X

Yi

75

.

0

6

.

3

ˆ +

=

667

.

0

)

493

.

0

(

35

.

1

)

ˆ

(

ˆ *

=

=

⇒ P

Y

e

s

)

667

.

0

)(

306

.

2

(

1

.

8

%

95 ±

:

CI ]

64

.

9

,

56

.

6

[

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 2 - 79

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-92-2048.jpg)

![.

.

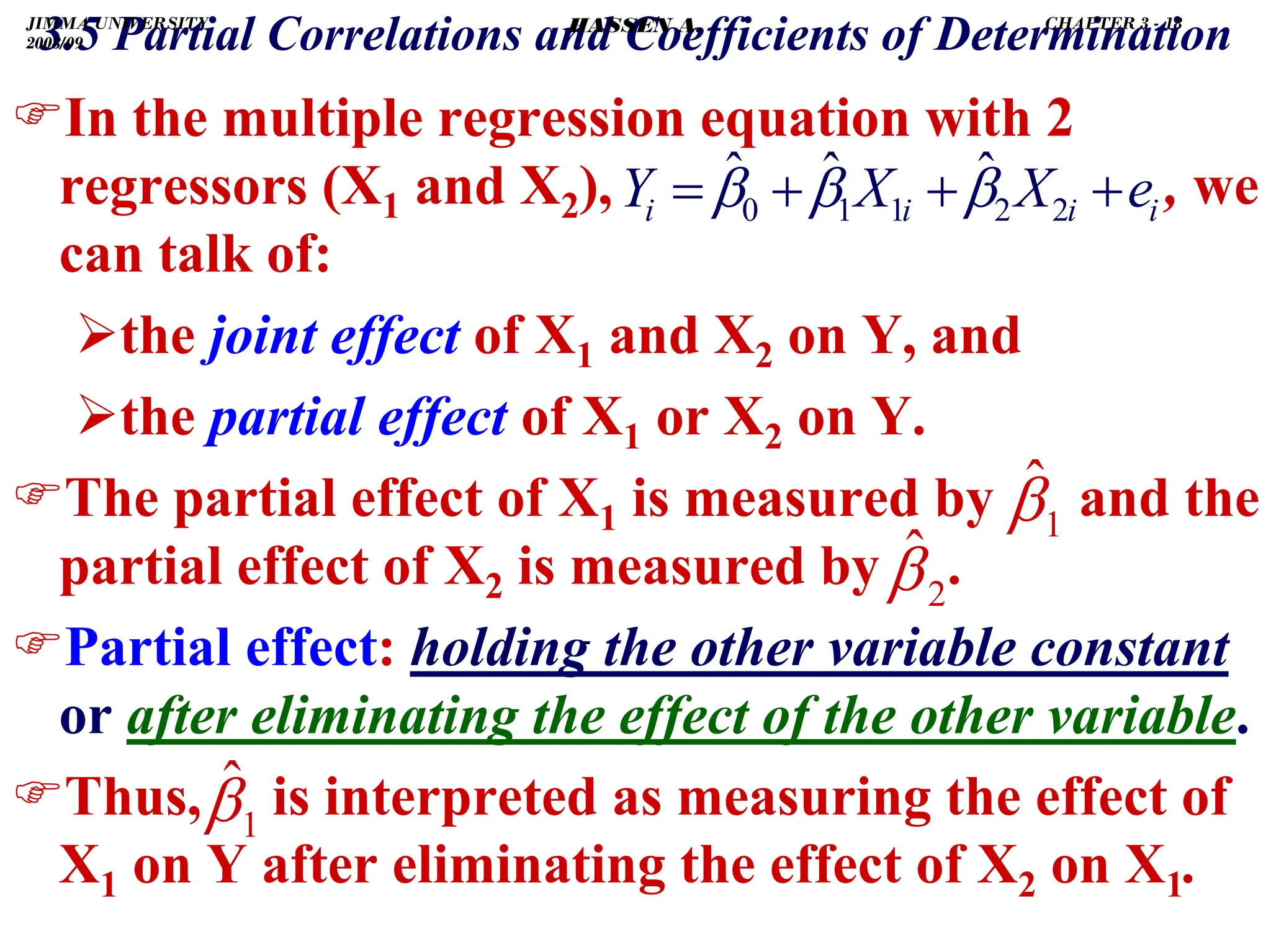

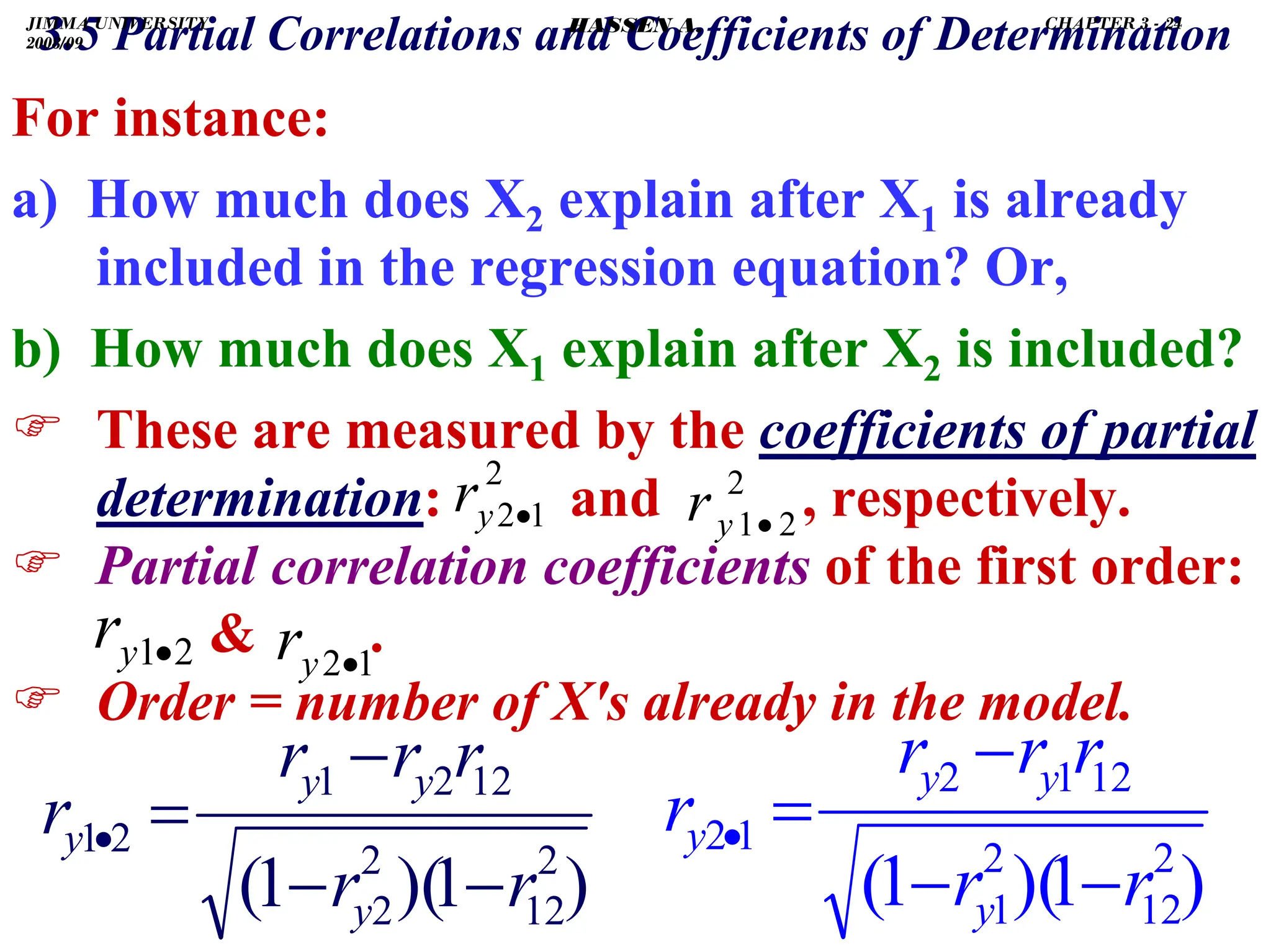

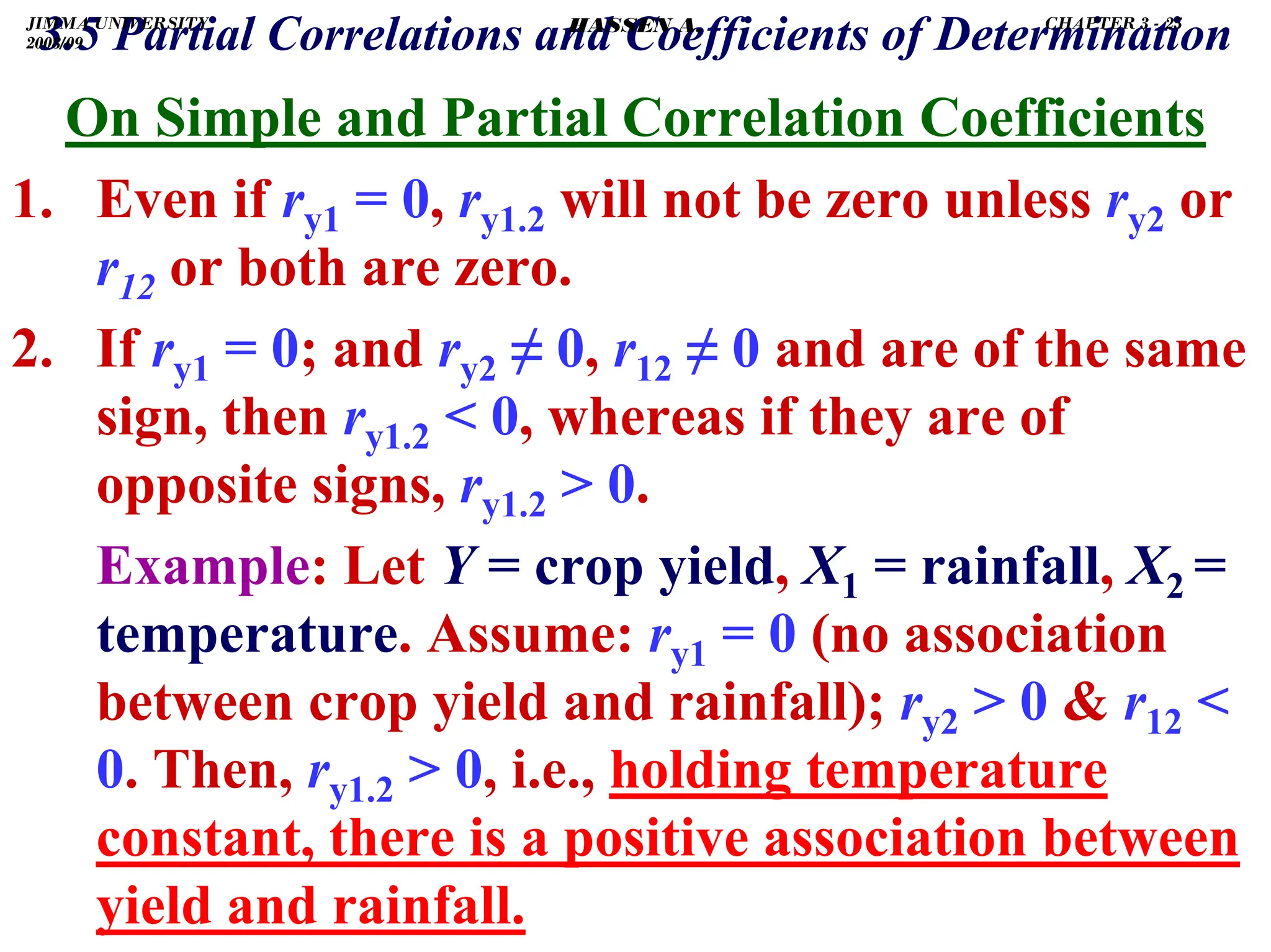

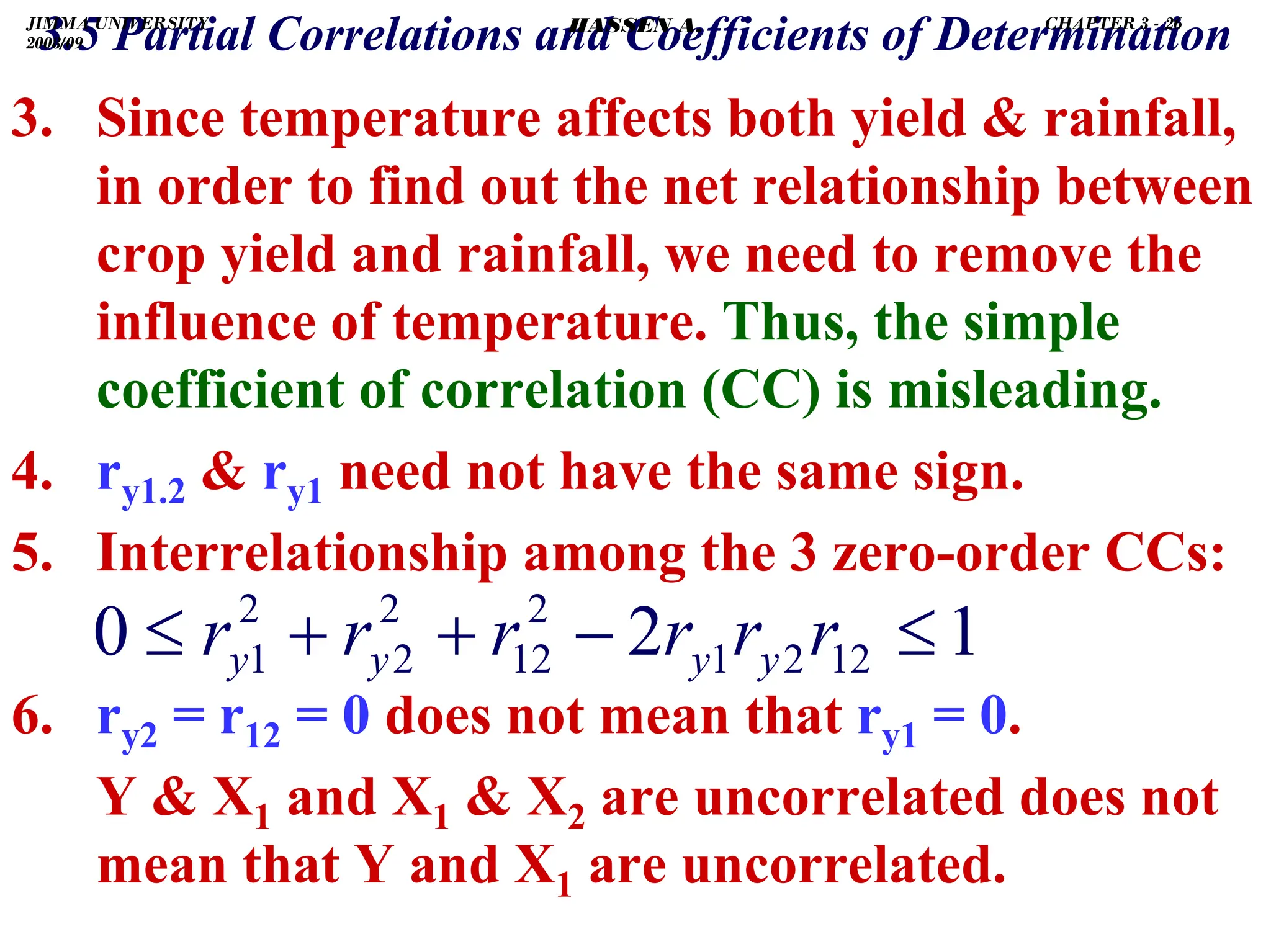

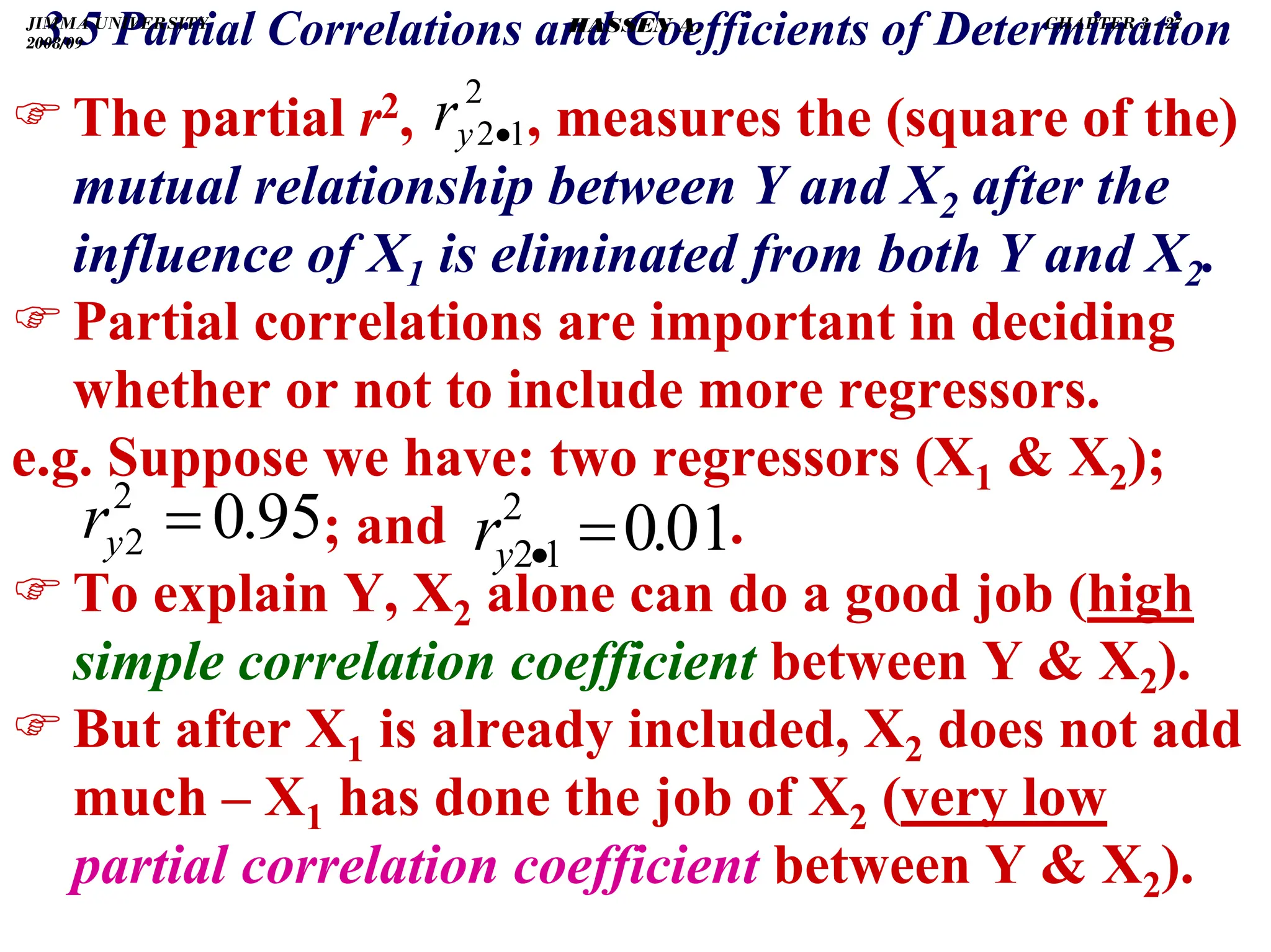

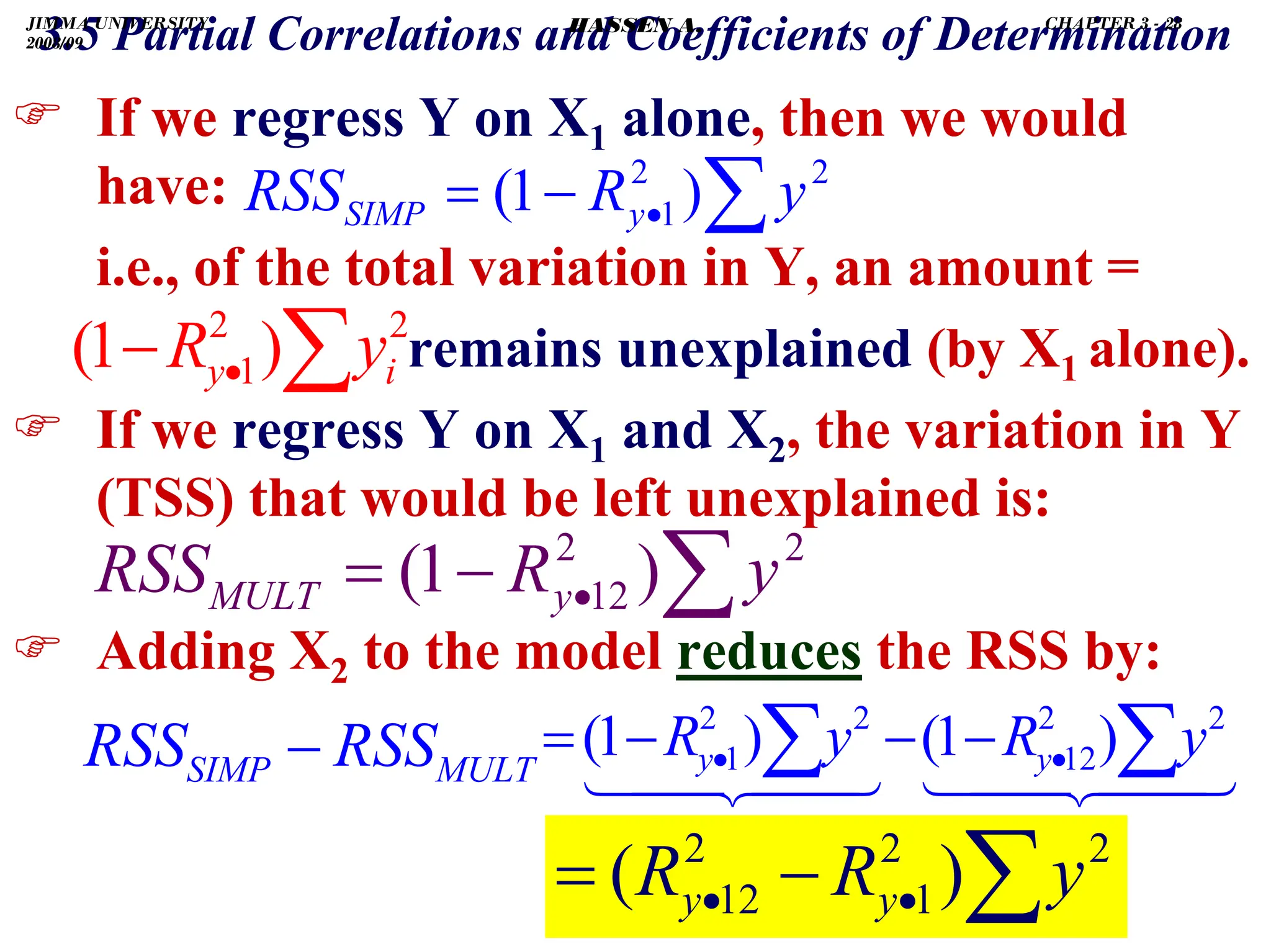

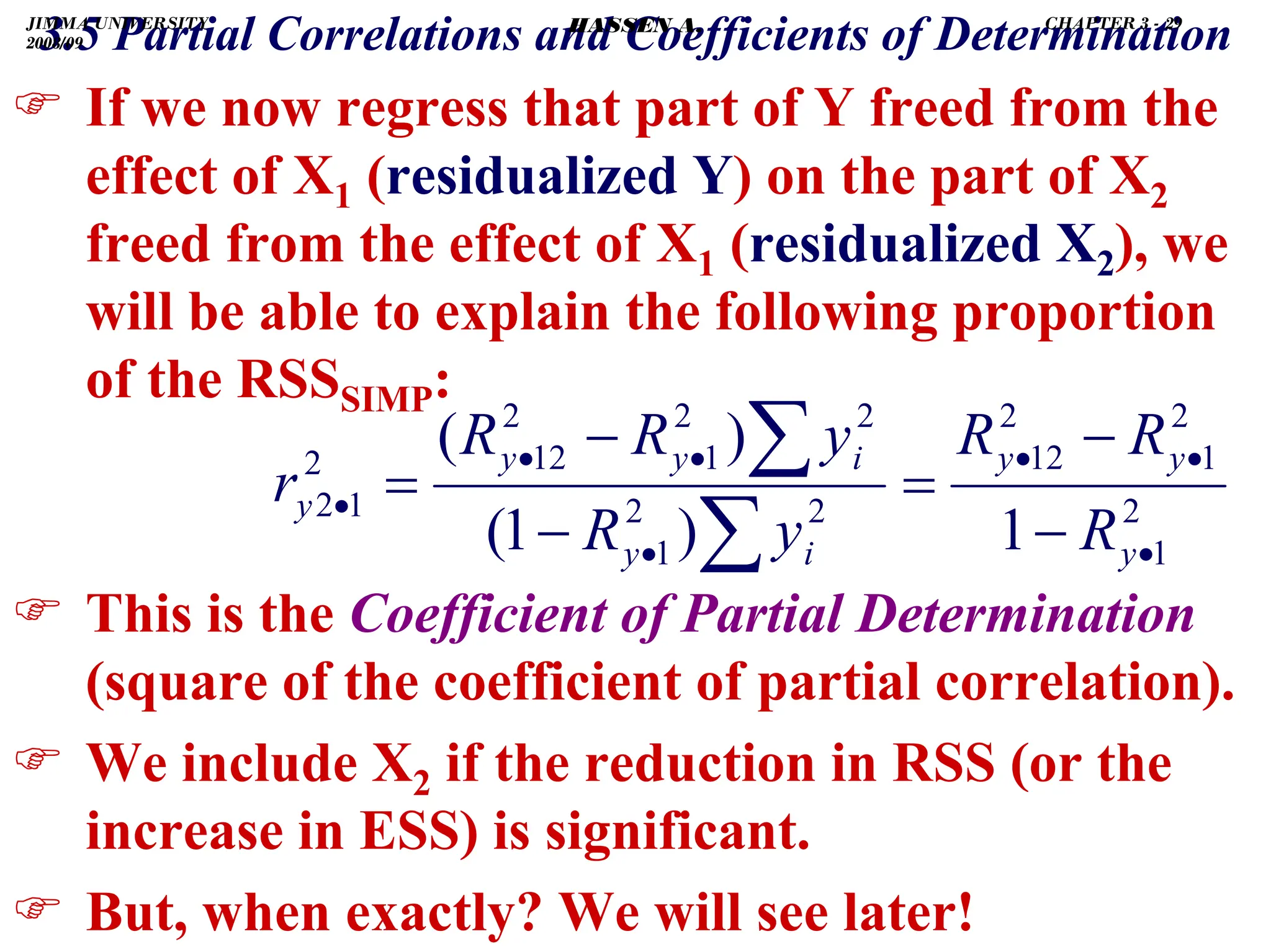

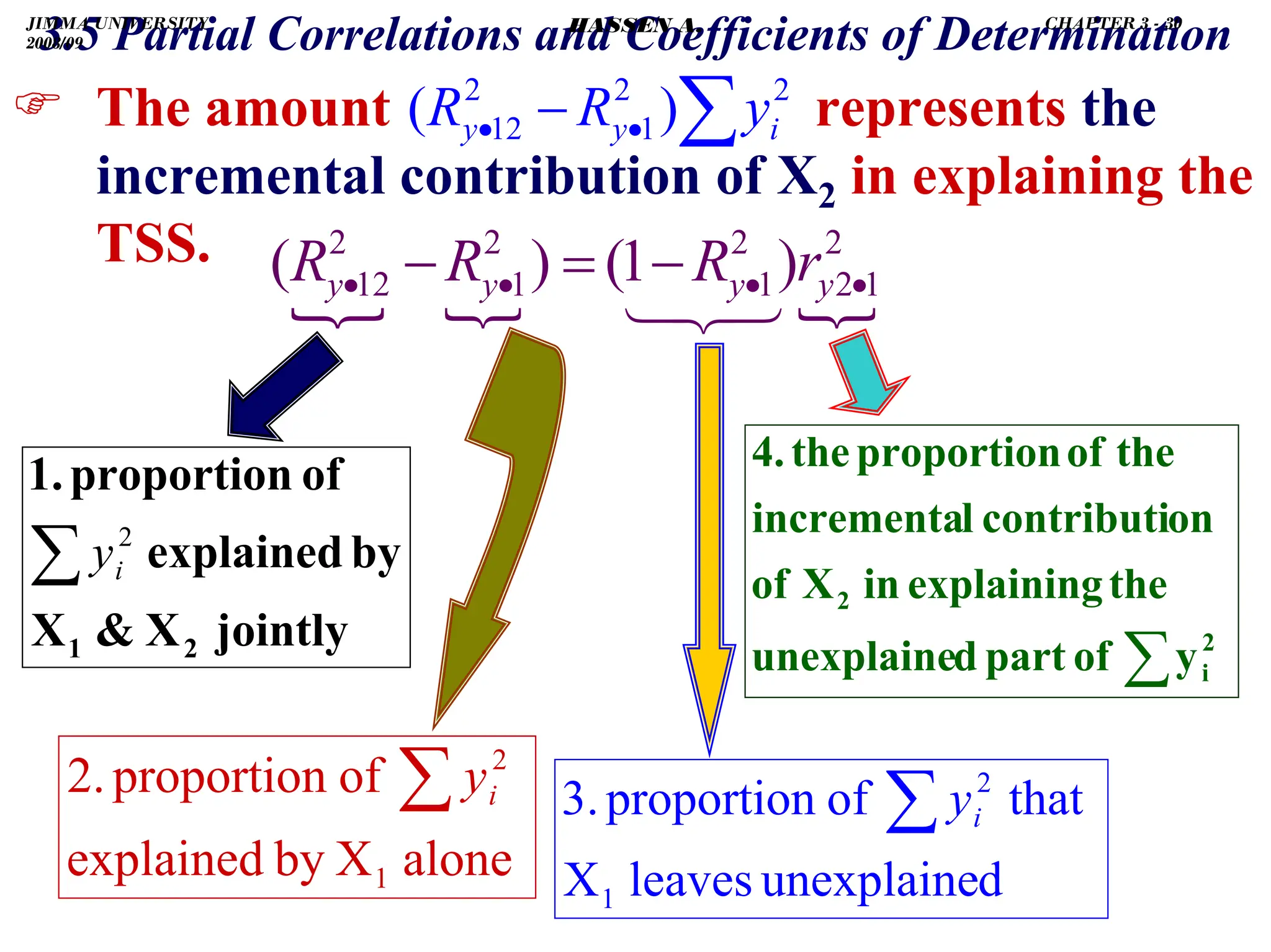

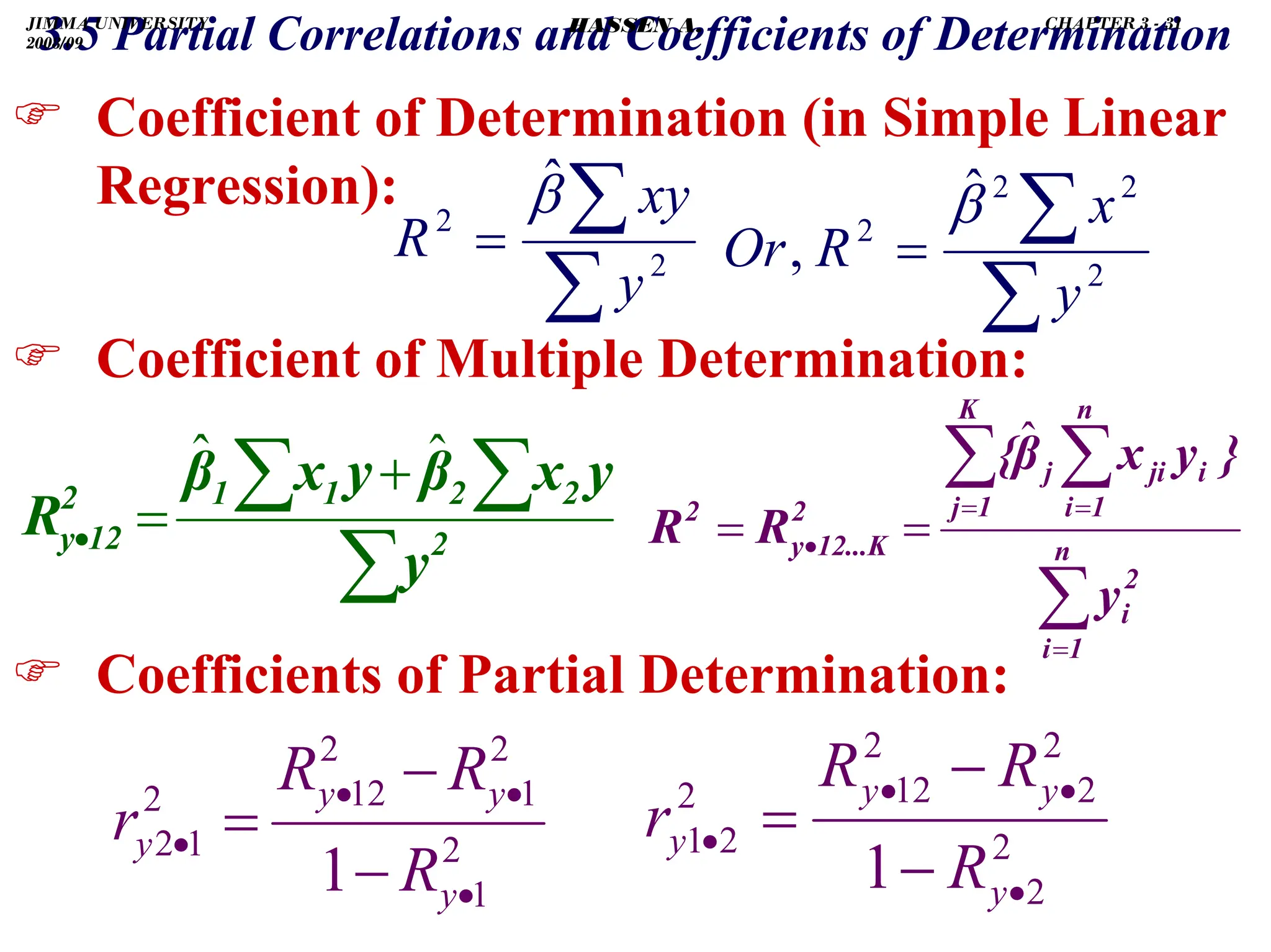

3.5 Partial Correlations and Coefficients of Determination

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

−

+

−

=

⇒

2

1

2

2

2

1

2

2

2

2

2

2

1

2

1

2

2

2

2

1

1

)

(

2

)

(

)

(

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

yx

x

x

x

yx

bye

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

−

+

−

=

⇒

2

2

2

2

1

2

2

2

2

1

2

1

2

2

2

2

1

1

2

2

)

(

2

)

(

]

[

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

yx

x

x

yx

x

bye

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

−

−

=

2

2

2

2

1

2

2

2

1

2

2

2

2

1

1

2

2

]

)

(

[

]

[

x

x

x

x

x

x

yx

x

x

yx

x

bye

2

2

1

2

2

2

1

2

2

1

1

2

2

)

(∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

−

−

=

x

x

x

x

yx

x

x

yx

x

bye

1

β̂

=

⇒ ye

b

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 3 - 21

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-116-2048.jpg)

![.

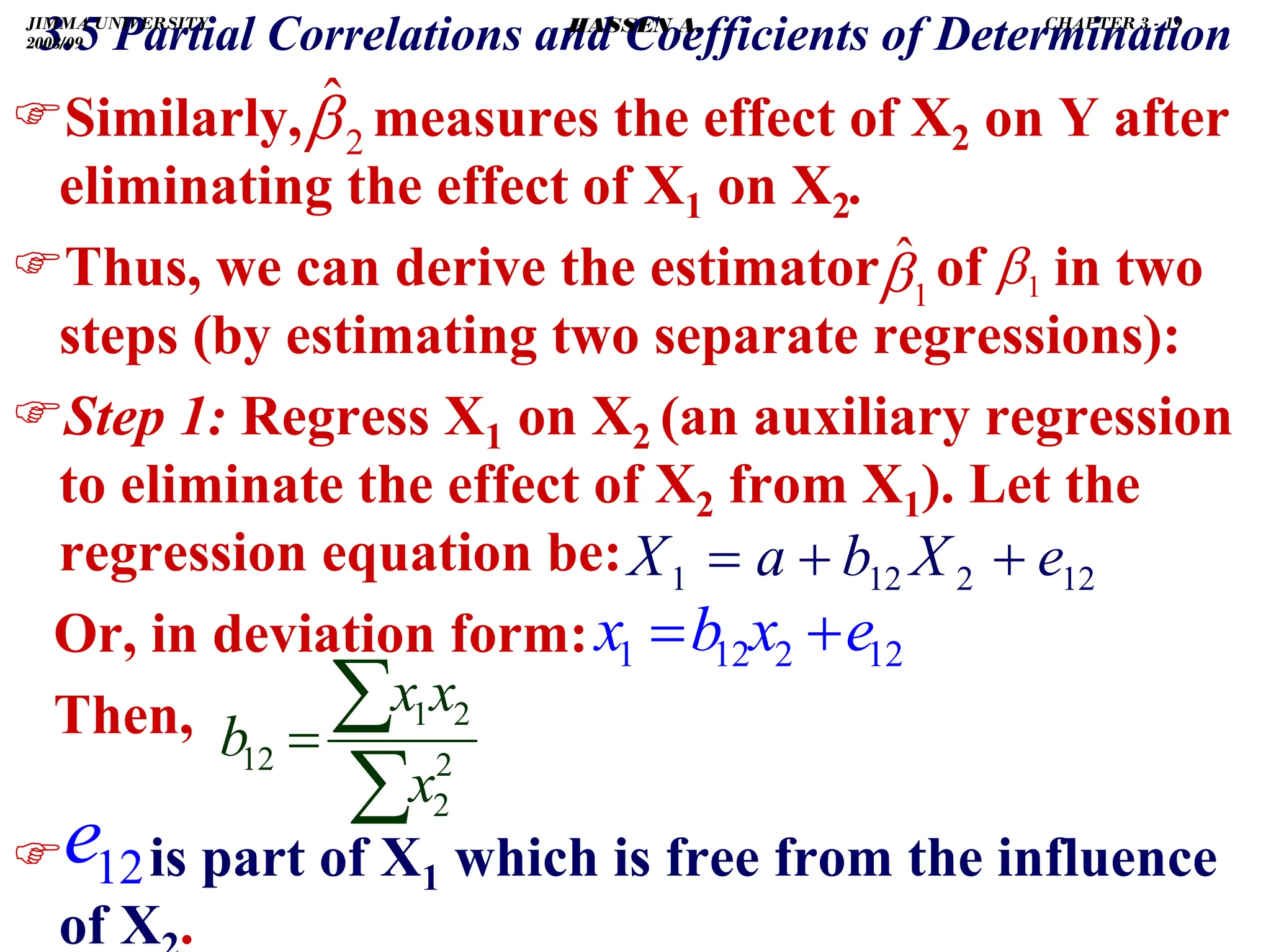

)Alternatively, we can derive the estimator of

as follows:

)Step 1: regress Y on X2, save the residuals, ey2.

…... [ey2 = residualized Y]

)Step 2: regress X1 on X2, save the residuals, e12.

…… [e12 = residualized X1]

)Step 3: regress ey2 (that part of Y cleared of the

influence of X2) on e12 (part of X1 cleared of the

influence of X2).

12

2

12

1

.

2 e

x

b

x

3.5 Partial Correlations and Coefficients of Determination

+

=

2

2

2

.

1 y

y e

x

b

y +

=

u

e

y +

= 12

12

2

e

.

3 α

!

ˆ

ˆ

ˆ

)

3

(

, 2

2

1

1 e

x

β

x

β

in y

sion

in regres

Then +

+

=

= 1

12 β

α

1

ˆ

β 1

β

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 3 - 22

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-117-2048.jpg)

![.

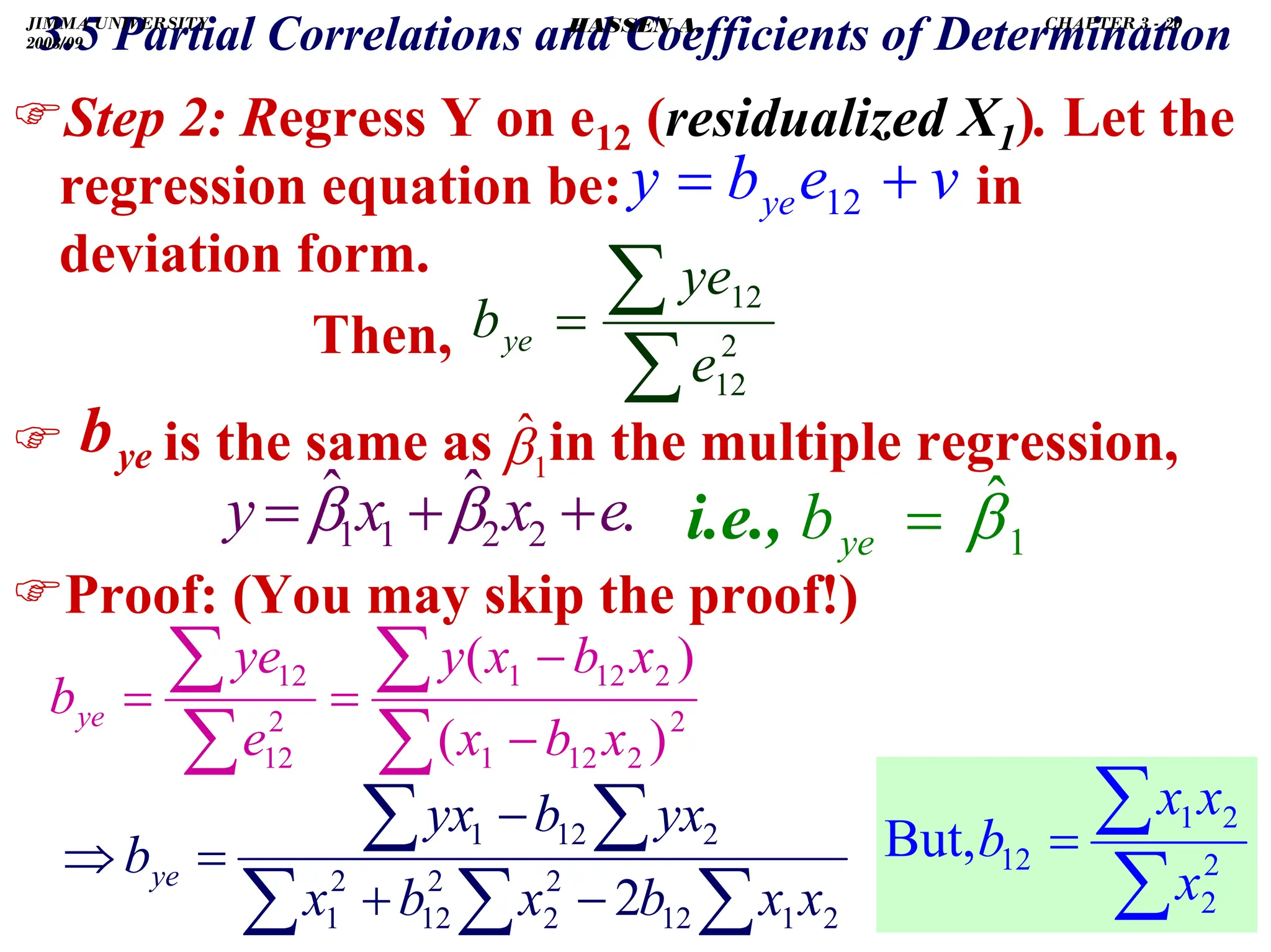

3.5 Partial Correlations and Coefficients of Determination

(Dividing TSS and RSS by their df).

)K + 1 represents the number of parameters to be

estimated.

∑

∑

∑

∑ −

=

= 2

2

2

2

2

1

ˆ

y

e

y

y

R

]

[

]

[

1

n

y

1)

(K

n

e

1

R 2

2

2

−

+

−

−

=

∑

∑

]

1

1

[

1 2

2

2

−

−

−

•

−

=

∑

∑

K

n

n

y

e

R

)

1

1

(

)

1

(

1 2

2

−

−

−

•

−

−

=

K

n

n

R

R

)

1

1

(

)

1

(

1 2

2

−

−

−

•

−

=

−

K

n

n

R

R

2

2

2

2

2

2

1

1

,

1

R

R

R

R

R

R

K

≤

⇒

−

−

≥

general,

In

as

long

As

.

),

to

(relative

larger

grows

n

As

2

2

R

R

K →

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 3 - 34

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-129-2048.jpg)

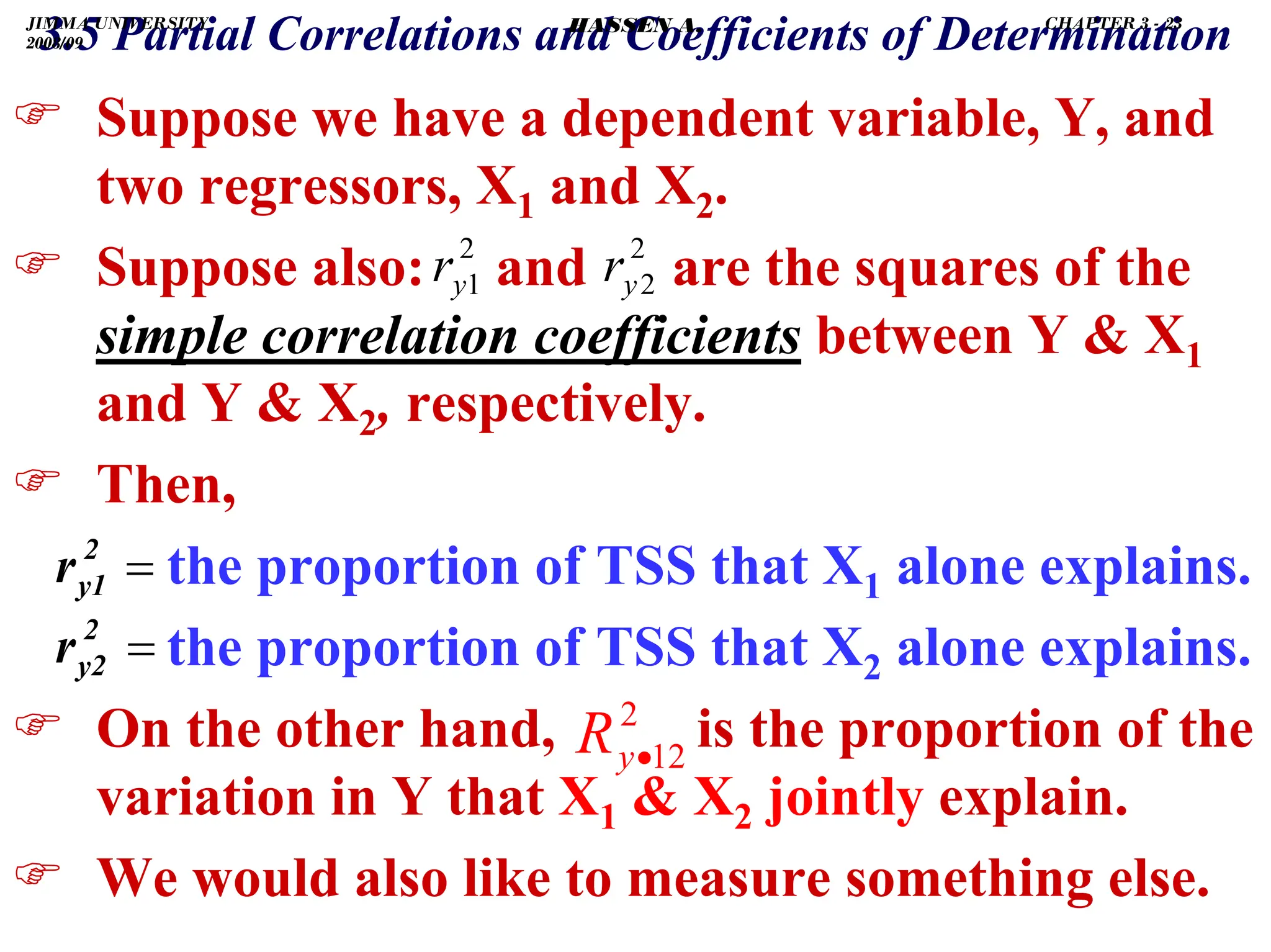

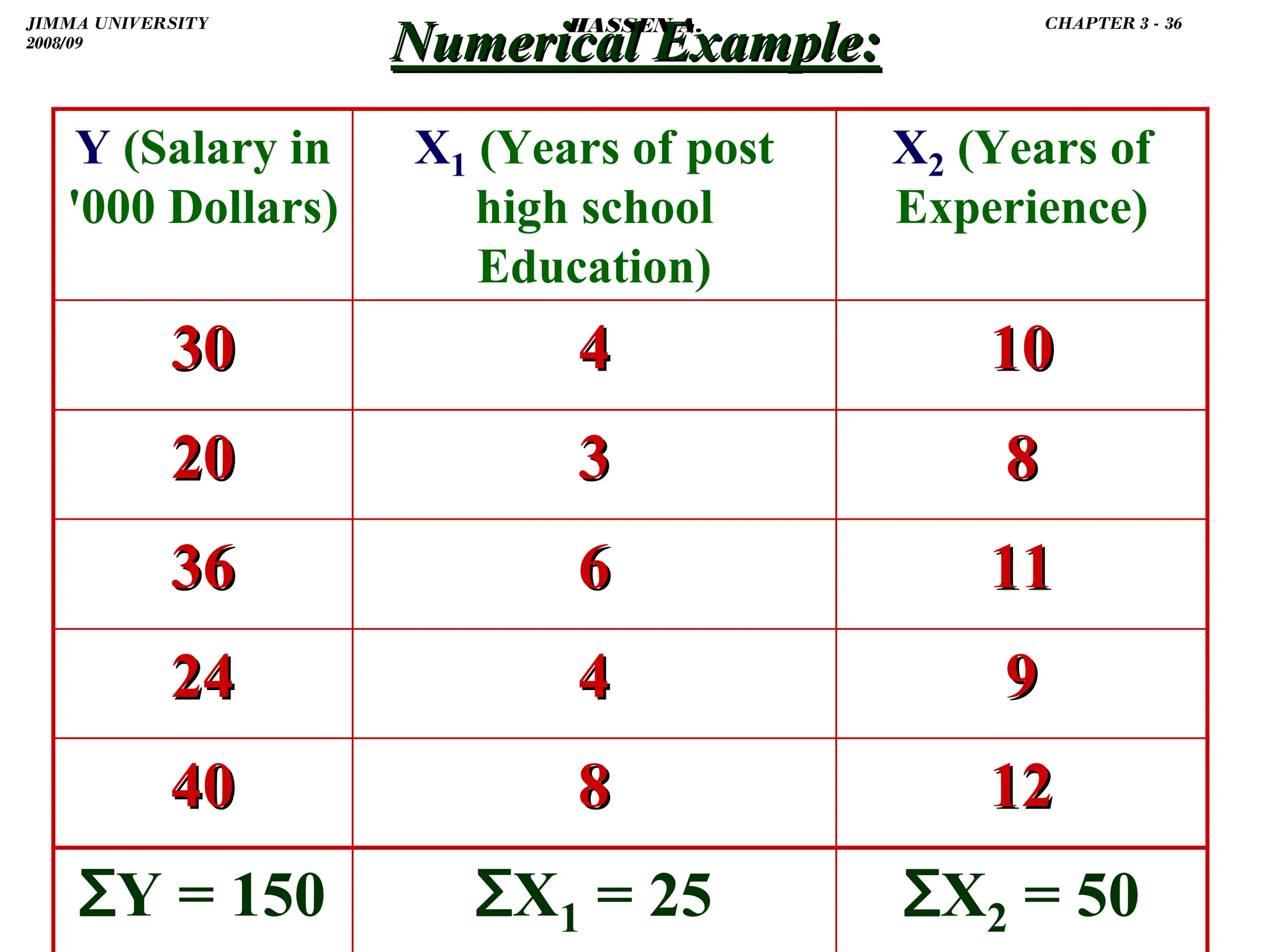

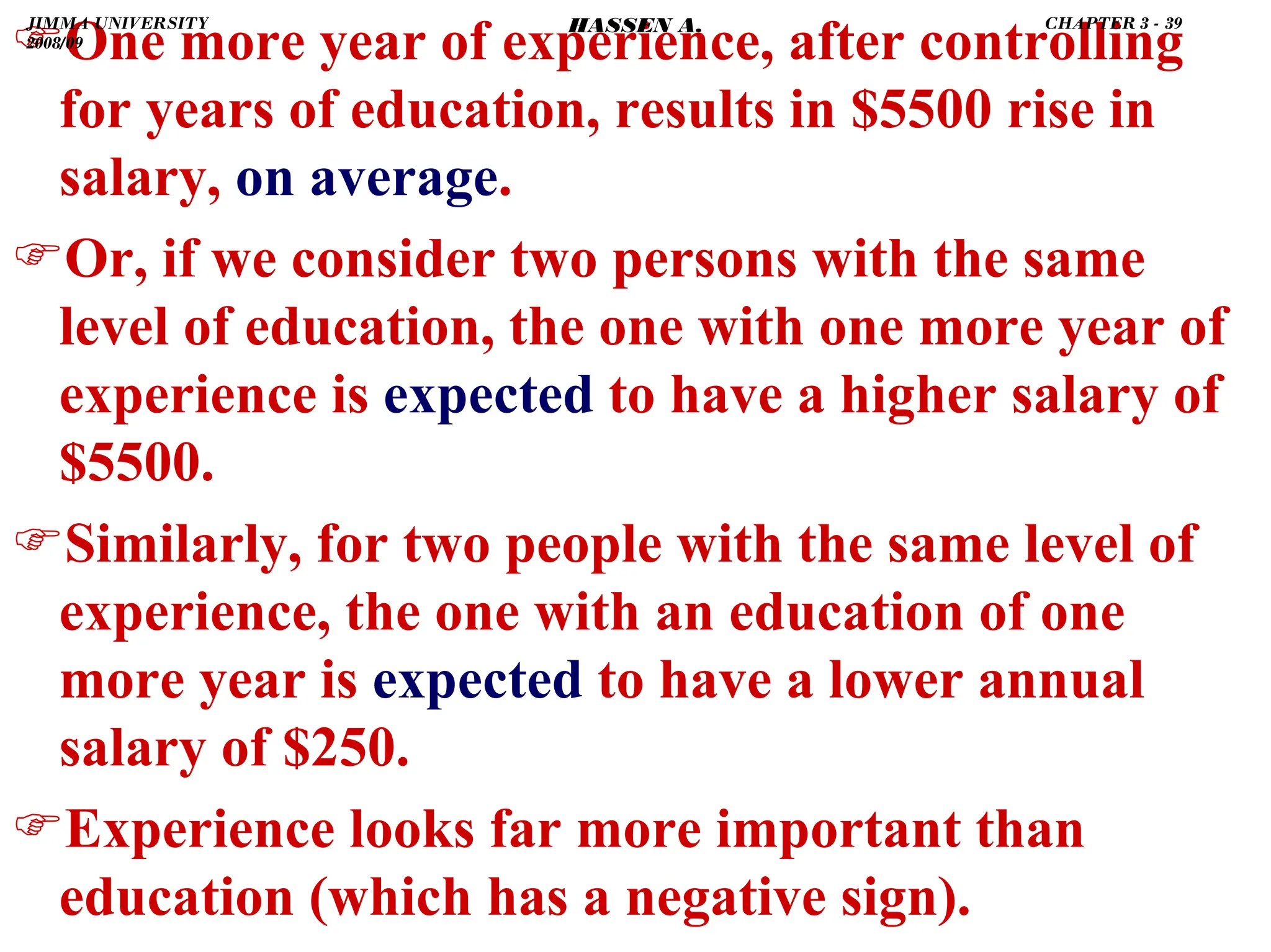

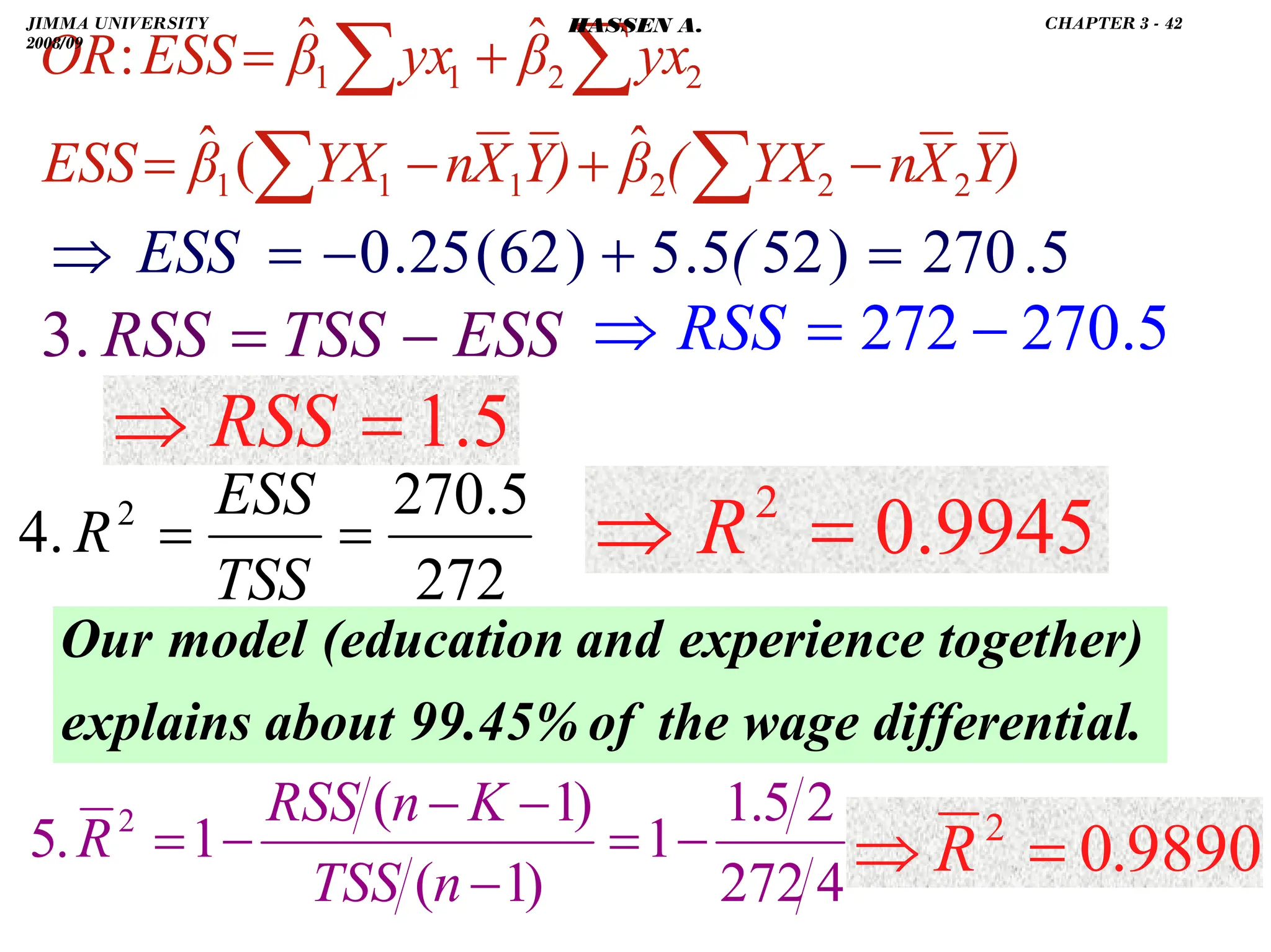

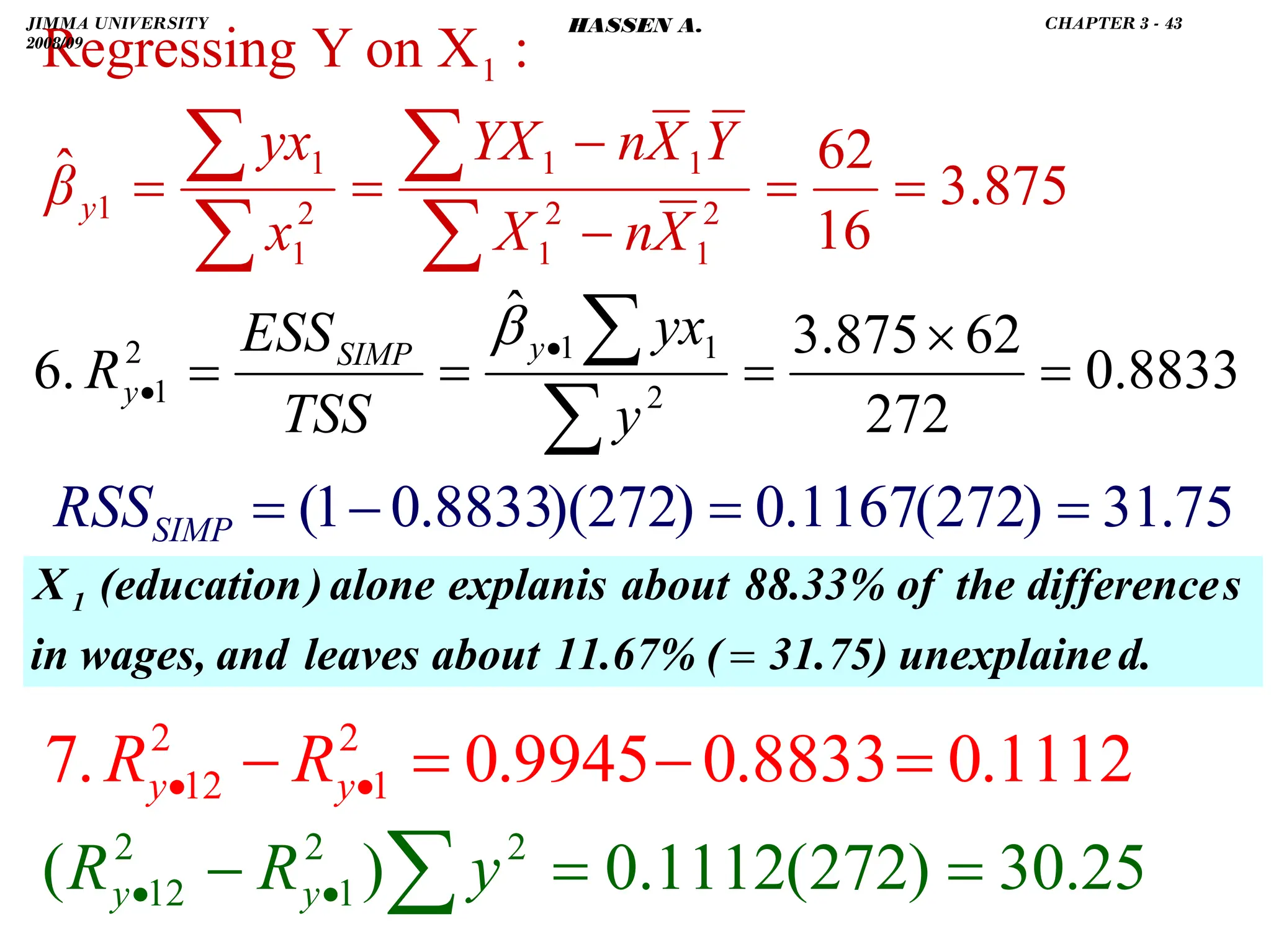

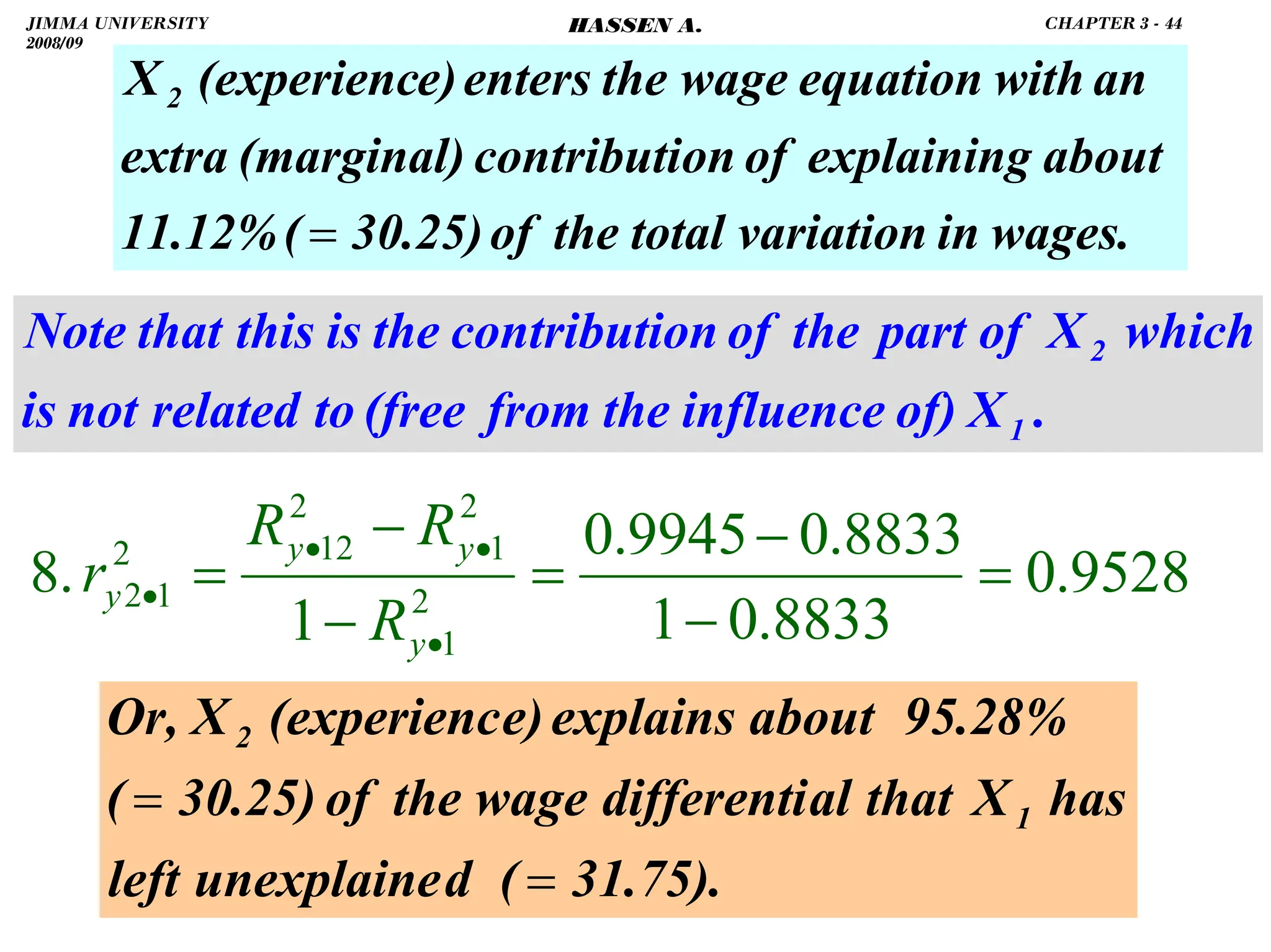

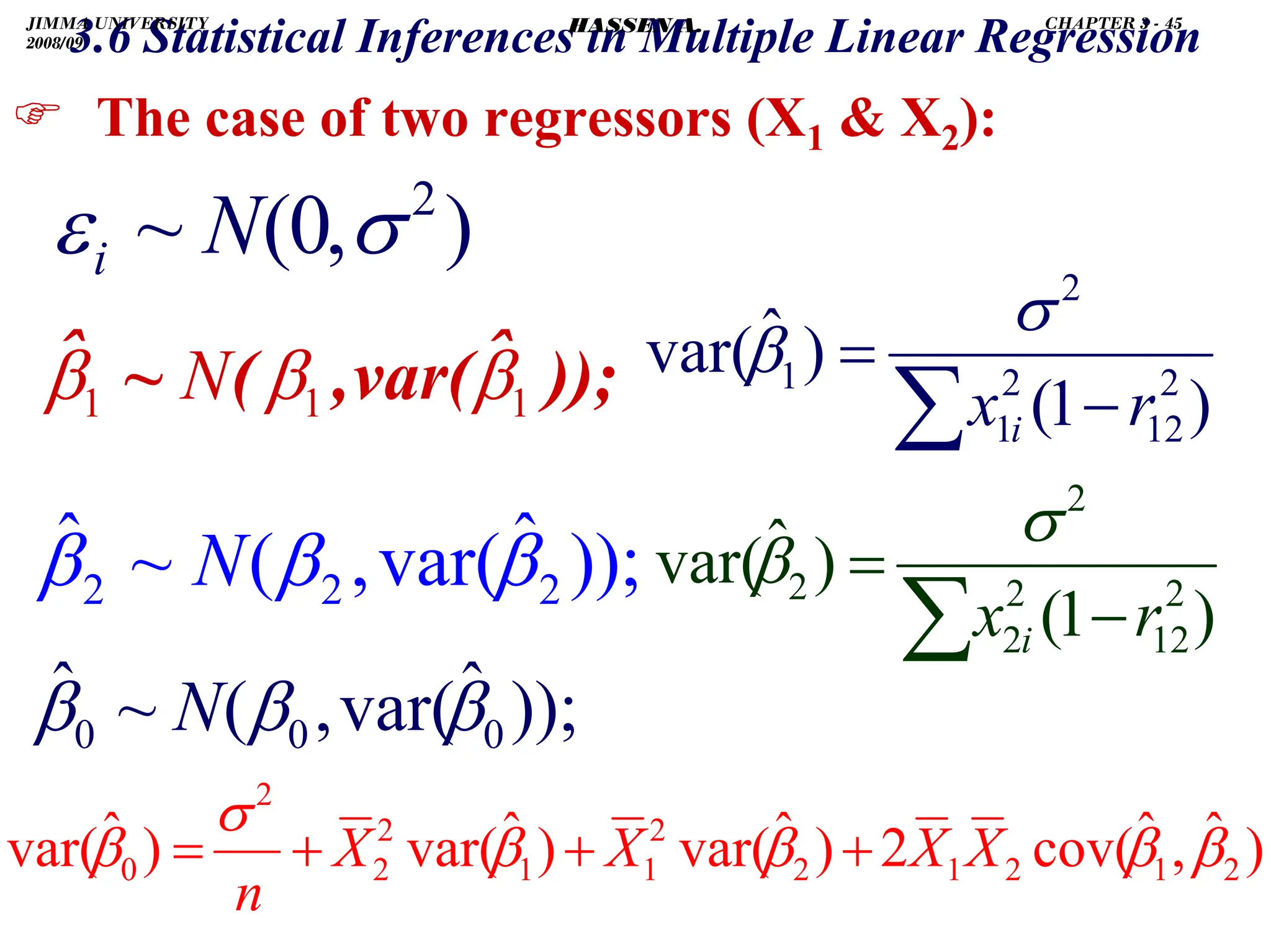

![.

∑

∑ +

=

= 2

2

2

1

1

2 ˆ

ˆ

ˆ

.

2 )

x

β

x

β

(

y

ESS

2

2

2

.

1 Y

n

Y

y

TSS −

=

= ∑

∑

5(5)(10)]

[262

0.25)(5.5)

2(

]

5(10)

[510

(5.5)

]

5(5)

[141

0.25)

(

ESS 2

2

2

2

−

−

+

−

+

−

−

=

)

X

X

n

X

X

(

β

β

)

X

n

X

(

β

)

X

n

X

(

β

ESS

2

1

2

1

2

1

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

1

2

1

2

1

ˆ

ˆ

2

ˆ

ˆ

−

+

−

+

−

=

∑

∑

∑

270.5

ESS =

⇒

272

=

⇒ TSS

2

)

30

(

5

4772−

=

TSS

∑

∑

∑ +

+

= 2

1

2

1

2

2

2

2

2

1

2

1

ˆ

ˆ

2

ˆ

ˆ x

x

β

β

x

β

x

β

ESS

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 3 - 41

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-136-2048.jpg)

![.

)Requirement for estimation: n K+1.

)If the number of data points (n) is small, it may

be difficult to detect violations of assumptions.

)With small n, it is hard to detect heteroskedast-

icity or nonnormality of ɛi's even when present.

)Though none of the assumptions is violated, a

linear regression with small n may not have

sufficient power to reject βj = 0, even if βj ≠ 0.

)If [(K+1)/n] 0.4, it will often be difficult to fit

a reliable model.

) Rule of thumb: aim to have n ≥ 6X ideally n ≥ 10X.

4.2 Sample Size: Problems with Few Data Points

4.2 Sample Size: Problems with Few Data Points

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 4 - 9

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-163-2048.jpg)

![.

4.3 Multicollinearity

4.3 Multicollinearity

) But, substituting 2X1 for X2 in the 3rd equation

yields the 2nd equation.

) That is, one of the normal equations is in fact

redundant.

) Thus, we have only 2 independent equations (1

2 or 1 3) but 3 unknowns (β's) to estimate.

) As a result, the normal equations will reduce to:

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

+

+

=

+

+

=

2

1

2

1

1

0

1

1

2

1

0

2

2

i

i

i

i

i

i

X

X

X

Y

X

n

Y

]

ˆ

ˆ

[

ˆ

]

ˆ

ˆ

[

ˆ

β

β

β

β

β

β

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 4 - 12

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-166-2048.jpg)

![.

4.3 Multicollinearity

4.3 Multicollinearity

)The number of β's to be estimated is greater

than the number of independent equations.

)So, if two or more X's are perfectly correlated, it

is not possible to find the estimates for all β's.

i.e., we cannot find separately, but .

⎟

⎟

⎠

⎞

⎜

⎜

⎝

⎛

+

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎣

⎡

=

⎟

⎟

⎠

⎞

⎜

⎜

⎝

⎛

⇒

∑

∑

∑

∑

∑

2

1

0

2

1

1

1

1 2β

β

β

ˆ

ˆ

ˆ

.

i

i

i

i

i

i

X

X

X

n

X

Y

Y

2

1 β̂

β̂ 2

1 β̂

2

β̂ +

2

1

2

1i

1

1i

i

2

1

X

n

X

Y

X

n

X

Y

β̂

2

β̂

α̂

−

−

=

+

=

∑

∑

1

2

1

0 X

]

β̂

2

β̂

[

Y

β̂ +

−

=

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 4 - 13

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-167-2048.jpg)

![.

4.4 Non

4.4 Non-

-normality of the Error Term

normality of the Error Term

)A formal test of normality is the Shapiro-Wilk

test [H0: errors are normally distributed].

)Large p-value shows that H0 cannot be rejected.

#In stata: swilk residual

)If H0 is rejected, transforming the regressand or

re-specifying (the functional form of) the model

may help.

)With large samples, thanks to the central limit

theorem, hypothesis testing may proceed even if

distribution of errors deviates from normality.

)Tests are generally asymptotically valid.

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 4 - 25

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-179-2048.jpg)

![.

) If heteroskedasticity is a result (or a reflection)

of specification error (say, omitted variables),

OLS estimators will be biased inconsistent.

) In the presence of heteroskedasticity, OLS is

not optimal as it gives equal weight to all

observations, when, in fact, observations with

larger error variances (σi

2) contain less

information than those with smaller σi

2 .

) To correct, give less weight to data points with

greater σi

2 and more weight to those with

smaller σi

2. [i.e., use GLS (WLS or FGLS)].

4.5.1

4.5.1 Heteroskedasticity

Heteroskedasticity

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 4 - 29

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-183-2048.jpg)

![.

4.5.1

4.5.1 Heteroskedasticity

Heteroskedasticity

B. A Formal Test:

) The most-often used test for heteroskedasticity

is the Breusch-Pagan (BP) test.

H0: homoskedasticity vs. Ha: heteroskedasticity

) Regress ũ2 on Ŷ or ũ2 on the original X's, X2's

and, if enough data, cross-products of the X's.

) H0 will be rejected for high values of the test

statistic [n*R2~χ2

q] or for low p-values.

) n R2 are obtained from the auxiliary

regression of ũ2 on q (number of) predictors.

# In stata (after regression): hettest or hettest, rhs

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 4 - 32

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-186-2048.jpg)

![.

) In general, stochastic regressors may or may

not be correlated with the model error term.

1. If X ɛ are independently distributed, E(ɛ|X)

= 0, OLS retains all its desirable properties.

2. If X ɛ are not independent but are either

contemporaneously uncorrelated, [E(ɛi|Xi±s) ≠

0 for s = 1, 2, … but E(ɛi|Xi) = 0], or ɛ X are

asymptotically uncorrelated, OLS retains its

large sample properties: estimators are biased,

but consistent and asymptotically efficient.

) The basis for valid statistical inference remains

but inferences must be based on large samples.

4.6.1 Stochastic Regressors and Measurement Error

4.6.1 Stochastic Regressors and Measurement Error

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 4 - 45

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-199-2048.jpg)

![.

4.6.3 Stability of Parameters and the Dummy

4.6.3 Stability of Parameters and the Dummy

Variables Regression

Variables Regression (DVR)

(DVR)

2. Estimate the pooled/combined model (under

H0: no significant change/difference in β's).

)The RSS from this model is the RRSS with

n–(K+1) df; where n = n1+n2.

3. Then, under H0, the test statistic will be:

4. Find the critical value: FK+1,n-2(K+1) from table.

5. Reject the null of stable parameters (and favor

Ha: that there is structural break) if Fcal Ftab.

1)]

2(K

[n

URSS

1)

(K

URSS]

[RRSS

F

+

−

+

−

=

cal

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 4 - 62

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-216-2048.jpg)

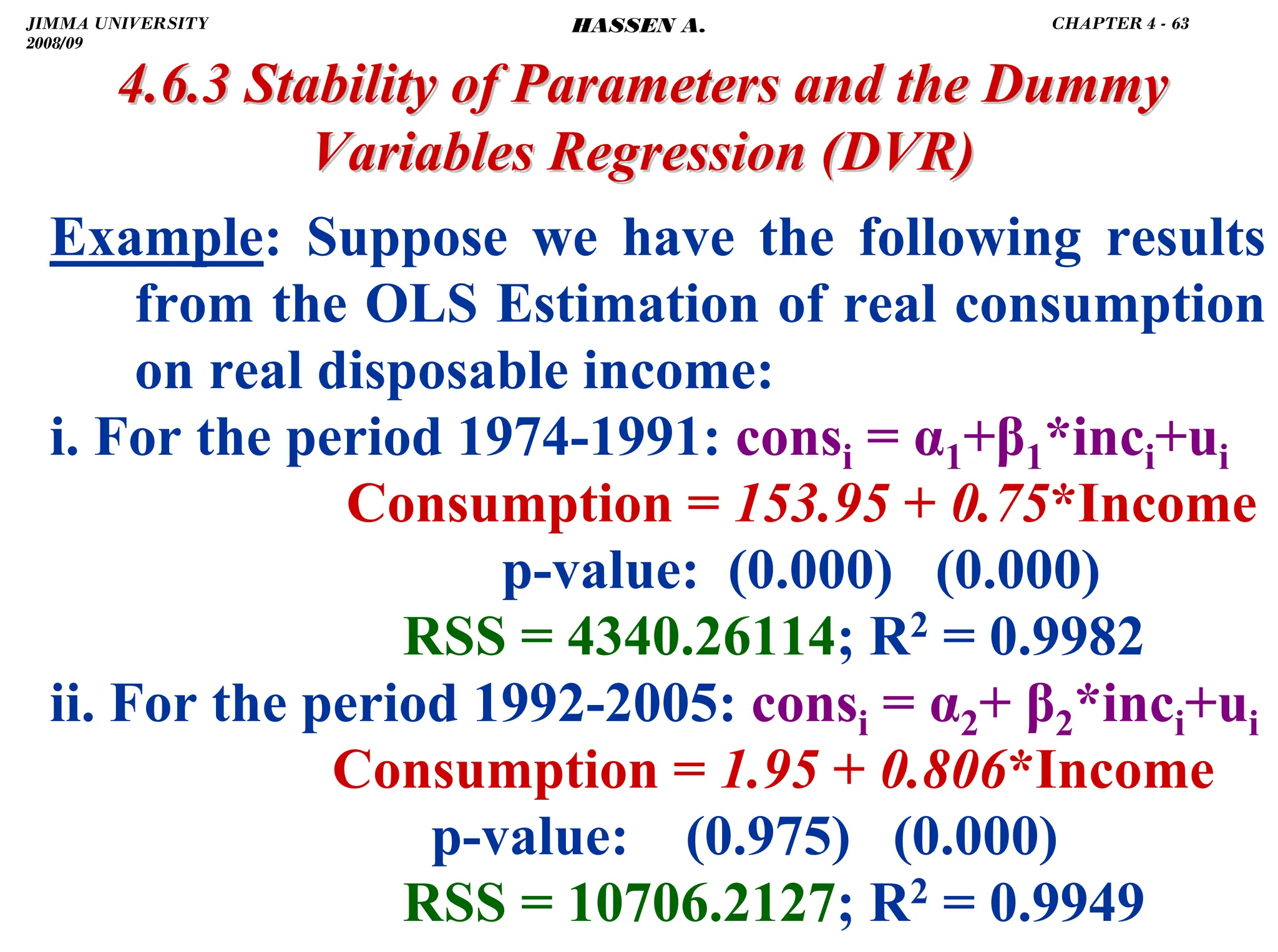

![.

4.6.3 Stability of Parameters and the Dummy

4.6.3 Stability of Parameters and the Dummy

Variables Regression

Variables Regression (DVR)

(DVR)

iii. For the period 1974-2005: consi = α+ β*inci+ui

Consumption = 77.64 + 0.79*Income

t-ratio: (4.96) (155.56)

RSS = 22064.6663; R2 = 0.9987

1. URSS = RSS1 + RSS2 = 15064.474

2. RRSS = 22064.6663

)K = 1 and K + 1 = 2; n1 = 18, n2 = 15, n = 33.

3. Thus,

4. p-value = Prob(F-tab 6.7632981) = 0.003883

6.7632981

29

15064.474

2

15064.474]

3

[22064.666

Fcal =

−

=

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 4 - 64

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-218-2048.jpg)

![.

4.6.3 Stability of Parameters and the Dummy

4.6.3 Stability of Parameters and the Dummy

Variables Regression

Variables Regression (DVR)

(DVR)

* The Chow test tells if the parameters differ on

average, but not which parameters differ.

* The Chow test requires that all groups have the

same error variance.

)This assumption is questionable: if parameters

can be different, then so can the variances be.

)One method of correcting for unequal error

variances is to use the dummy variable

approach with White's Robust Standard Errors.

1)

(K

n

RSS

n

]

RSS

[RRSS

F

1

1

2

1

cal

+

−

−

=

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 4 - 66

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-220-2048.jpg)

![.

)This is because with the method of DVR:

1. we run only one regression.

2. we can test whether the change is in the

intercept only, in the slope only, or in both.

In our example, the change is in both. Why???

)For a total of m categories, use m–1 dummies!

)Including m dummies (1 for each group) results

in perfect multicollinearity (the dummy

variable trap). e.g.: 2 groups 2 dummies:

)constant = D1 + D2 !!!

4.6.3 Stability of Parameters and the Dummy

4.6.3 Stability of Parameters and the Dummy

Variables Regression

Variables Regression (DVR)

(DVR)

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

=

1

0

X

1

0

1

X

1

0

1

X

1

X

13

12

11

]

D

D

[constant

X 2

1

=

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 4 - 73

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-227-2048.jpg)

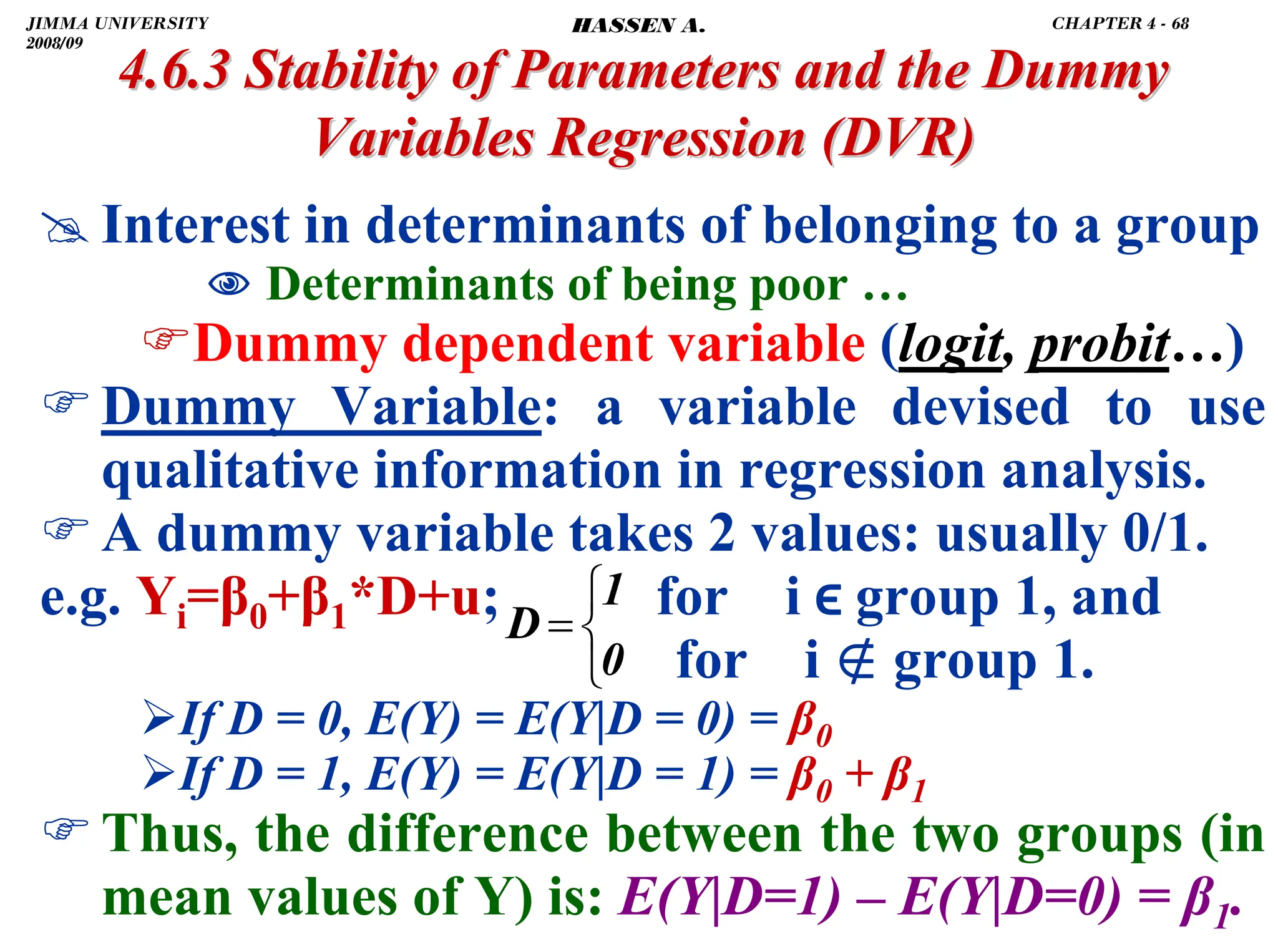

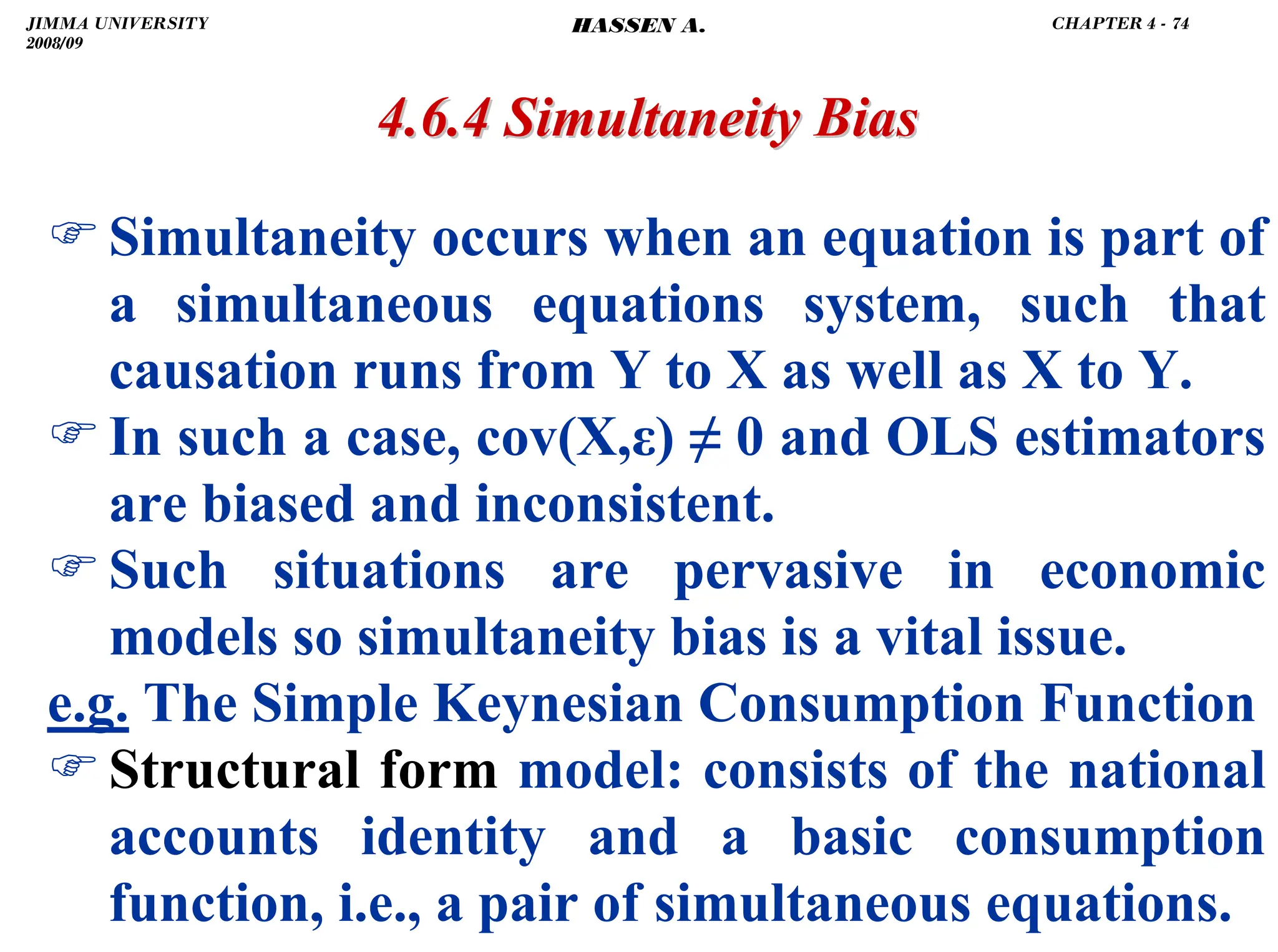

![.

)Yt Ct are endogenous (simultaneously

determined) and It is exogenous.

)Reduced form: expresses each endogenous

variable as a function of exogenous variables,

(and/or predetermined variables – lagged

endogenous variables, if present) and random

error term/s.

)The reduced form is:

4.6.4 Simultaneity Bias

4.6.4 Simultaneity Bias

⎪

⎪

⎩

⎪

⎪

⎨

⎧

+

+

−

=

+

+

−

=

]

t

U

t

βI

)[α

β

1

1

(

t

C

]

t

U

t

I

)[α

β

1

1

(

t

Y

⎩

⎨

⎧

+

+

=

+

=

t

t

t

t

t

t

U

βY

α

C

I

C

Y

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 4 - 75

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-229-2048.jpg)

![.

)The reduced form equation for Yt shows that:

)Yt, in Ct = α + βYt + Ut, is correlated with Ut.

)OLS estimators for β (MPC) α (autonomous

consumption) are biased and inconsistent.

)

) Solution

Solution: IV/2SLS

4.6.4 Simultaneity Bias

4.6.4 Simultaneity Bias

]

U

),

U

I

)(α

β

1

1

cov[(

)

U

,

cov(Y t

t

t

t

t +

+

−

=

)]

U

,

U

cov(

)

U

,

I

cov(

)

U

,

)[cov(α

β

1

1

( t

t

t

t

t +

+

−

=

0

)

β

1

(

)

)var(U

β

1

1

( t ≠

−

=

−

=

2

U

σ

JIMMA UNIVERSITY

2008/09

CHAPTER 4 - 76

HASSEN A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econometrics-lecturenotesa-240528134607-4226792a/75/ECONOMETRICS-introductory-and-LECTURE-NOTESa-pdf-230-2048.jpg)