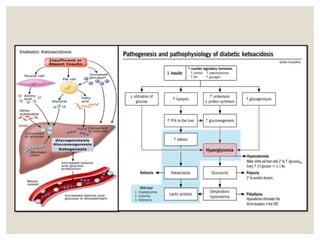

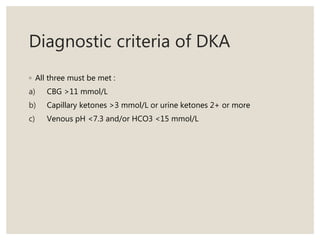

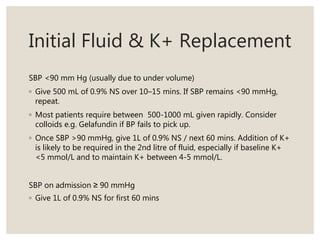

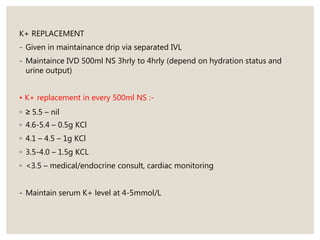

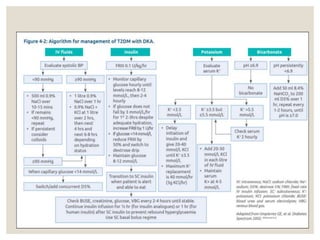

This document discusses diabetic emergencies including hypoglycemia, diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state (HHS). It provides details on the diagnostic criteria, symptoms, and general approach to managing patients with DKA. Key points include: DKA is caused by insulin deficiency leading to hyperglycemia and ketonemia; diagnostic criteria includes blood glucose over 11 mmol/L, ketones over 3 mmol/L, and venous pH below 7.3; symptoms include nausea, vomiting, and altered mental status; management involves assessing airway, breathing, circulation, and providing IV fluids and insulin.

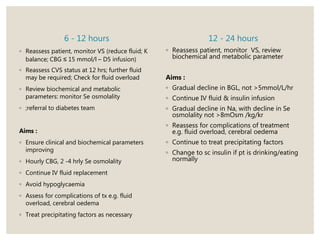

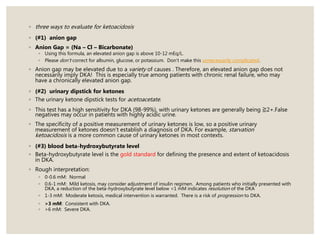

![Criteria For Severe Ketoacidosis

- need for ICU referral/ critical care

◦ Venous HCO3 <5 mmol/L

◦ Blood ketones >6 mmol/L

◦ Venous pH <7.1

◦ Anion Gap > 16 [Anion Gap = (Na+ + K+) – (Cl- + HCO3-)]

◦ GCS <12

◦ SPO2 <92% on air (ABG required)

◦ Systolic BP <90 mmHg

◦ Pulse >100 or <60 bpm](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dkahhsdayah-211119144016/85/Dka-and-HHS-pptx-23-320.jpg)

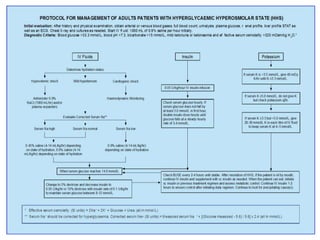

![Diagnostic Criteria of HHS

◦ Hypovolemia – dehydration

◦ Marked CBG > 33.3 mmol/l

◦ pH > 7.3, HCO3 > 15 mmol/l

◦ Urine or blood ketones nil or minimal

◦ Se osmolality > 320 mosmol/kg

Formula : (2 x serum

[Na]) + [glucose] + [urea]

(all in mmol/L)

Or laboratory measured value](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dkahhsdayah-211119144016/85/Dka-and-HHS-pptx-48-320.jpg)