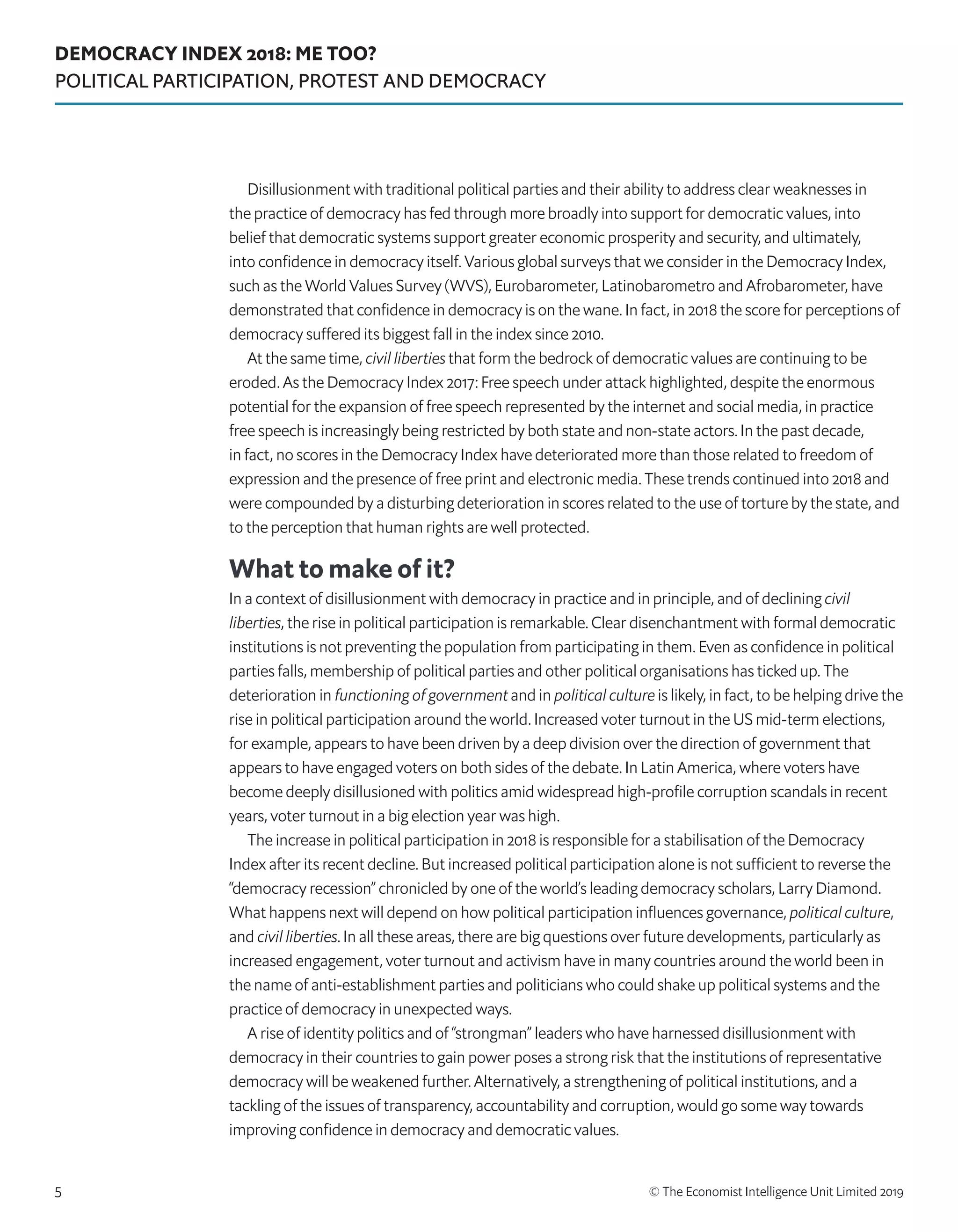

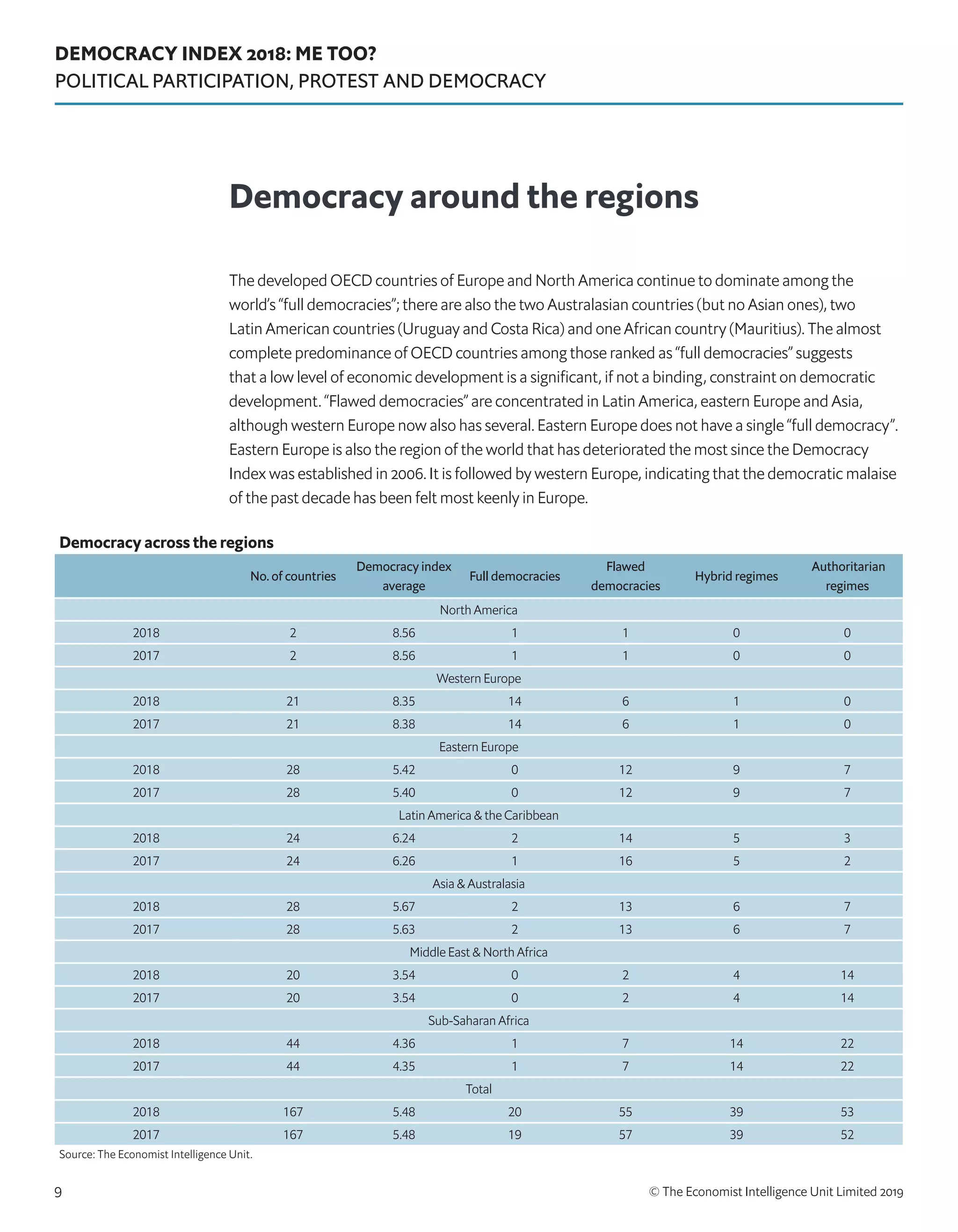

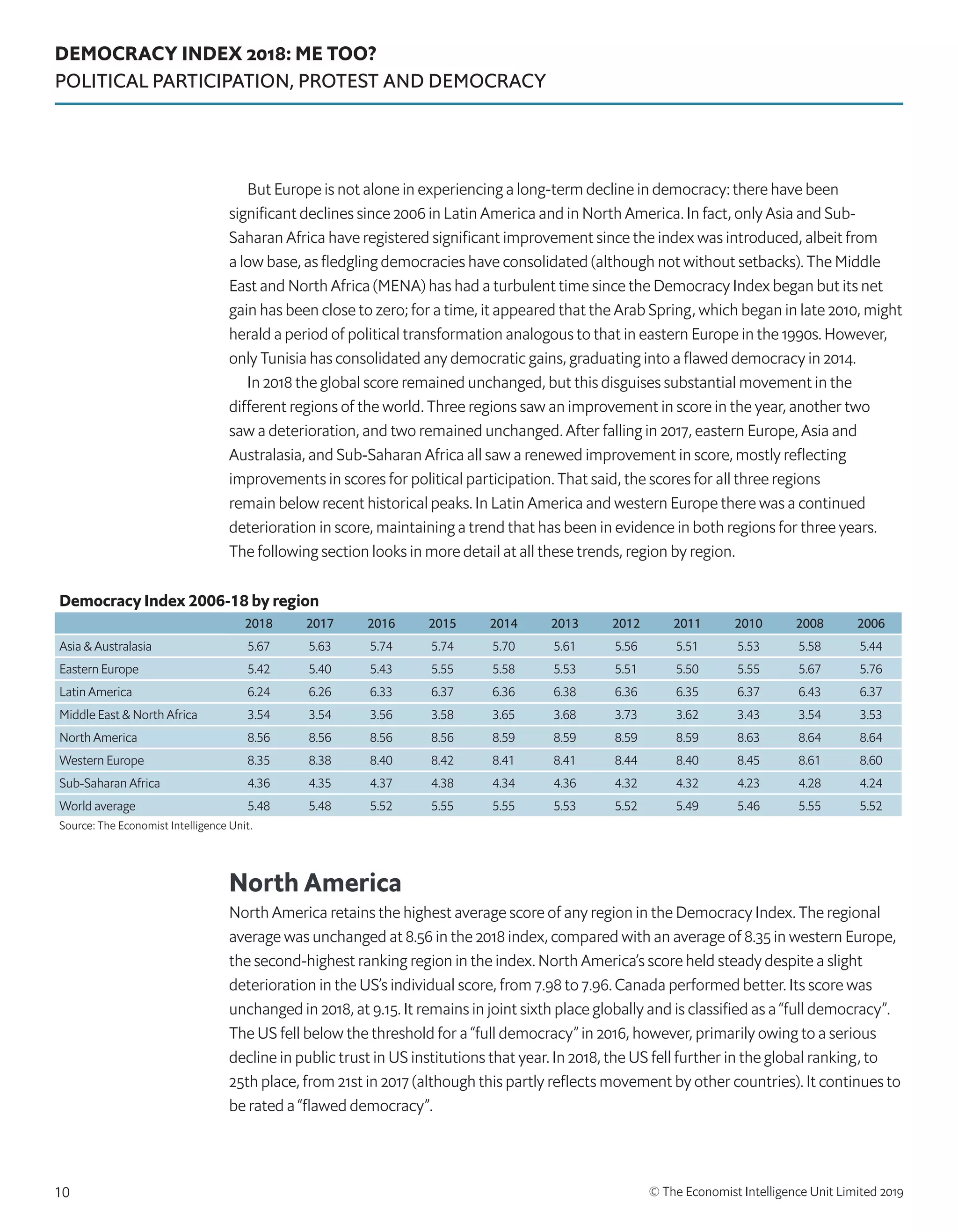

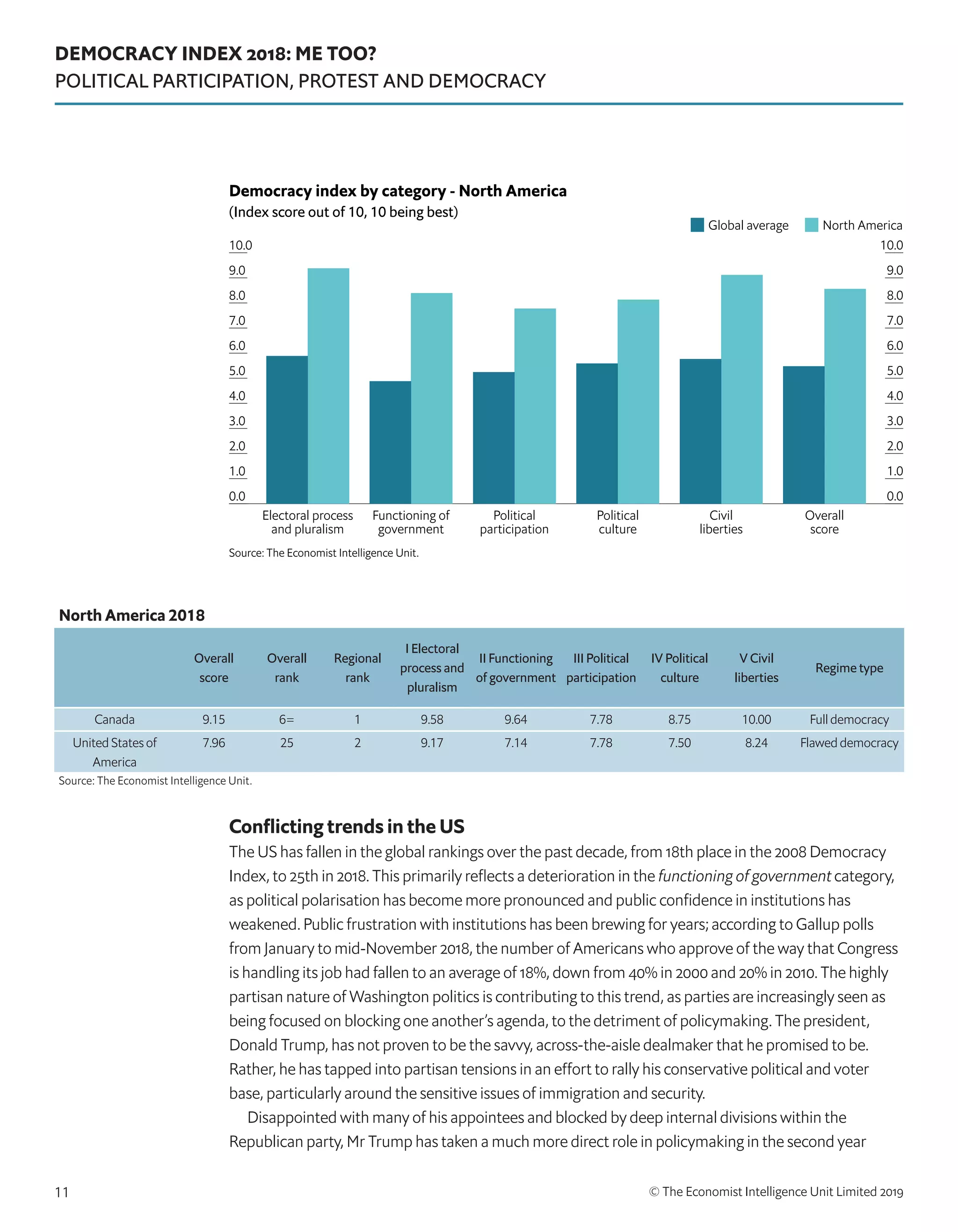

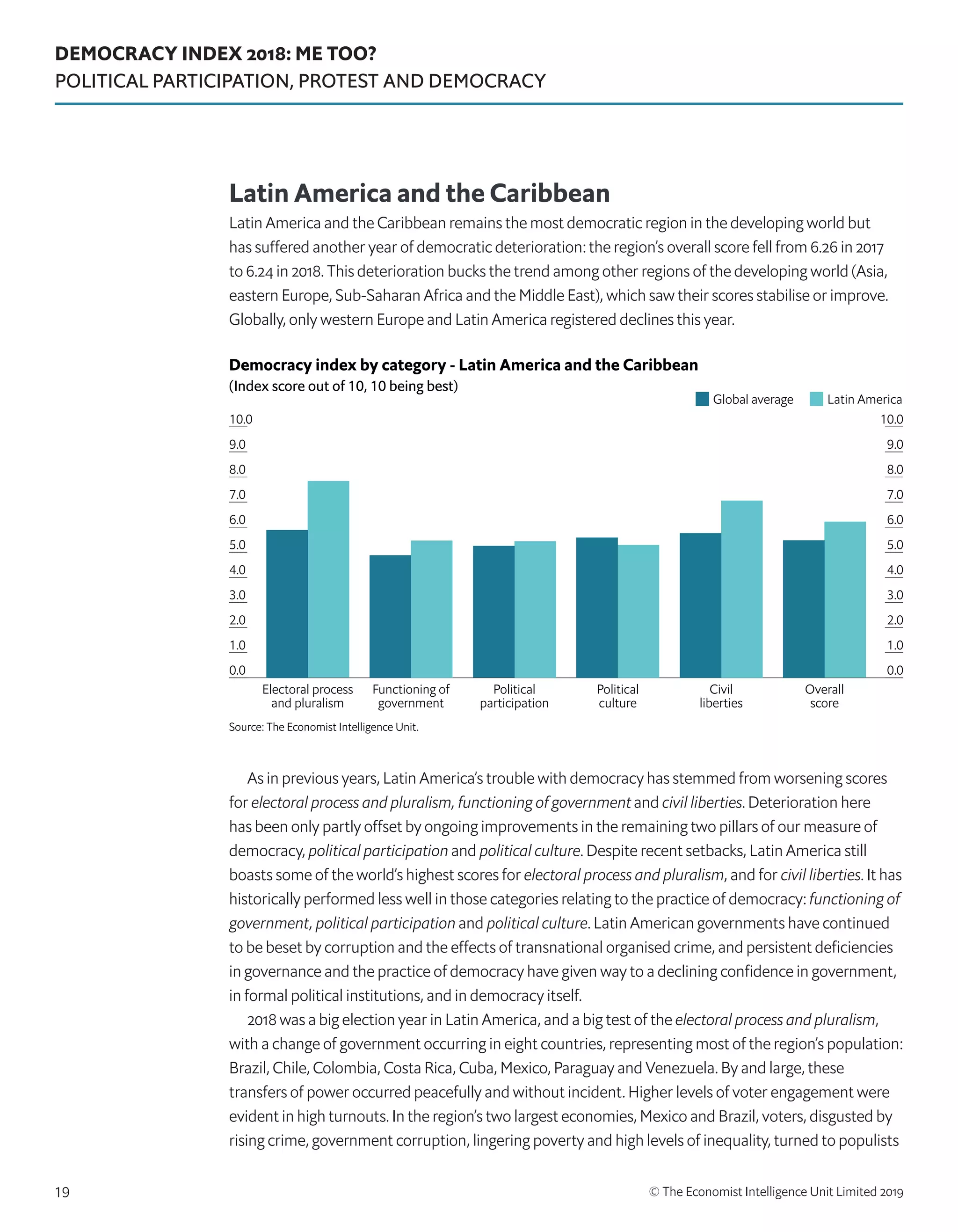

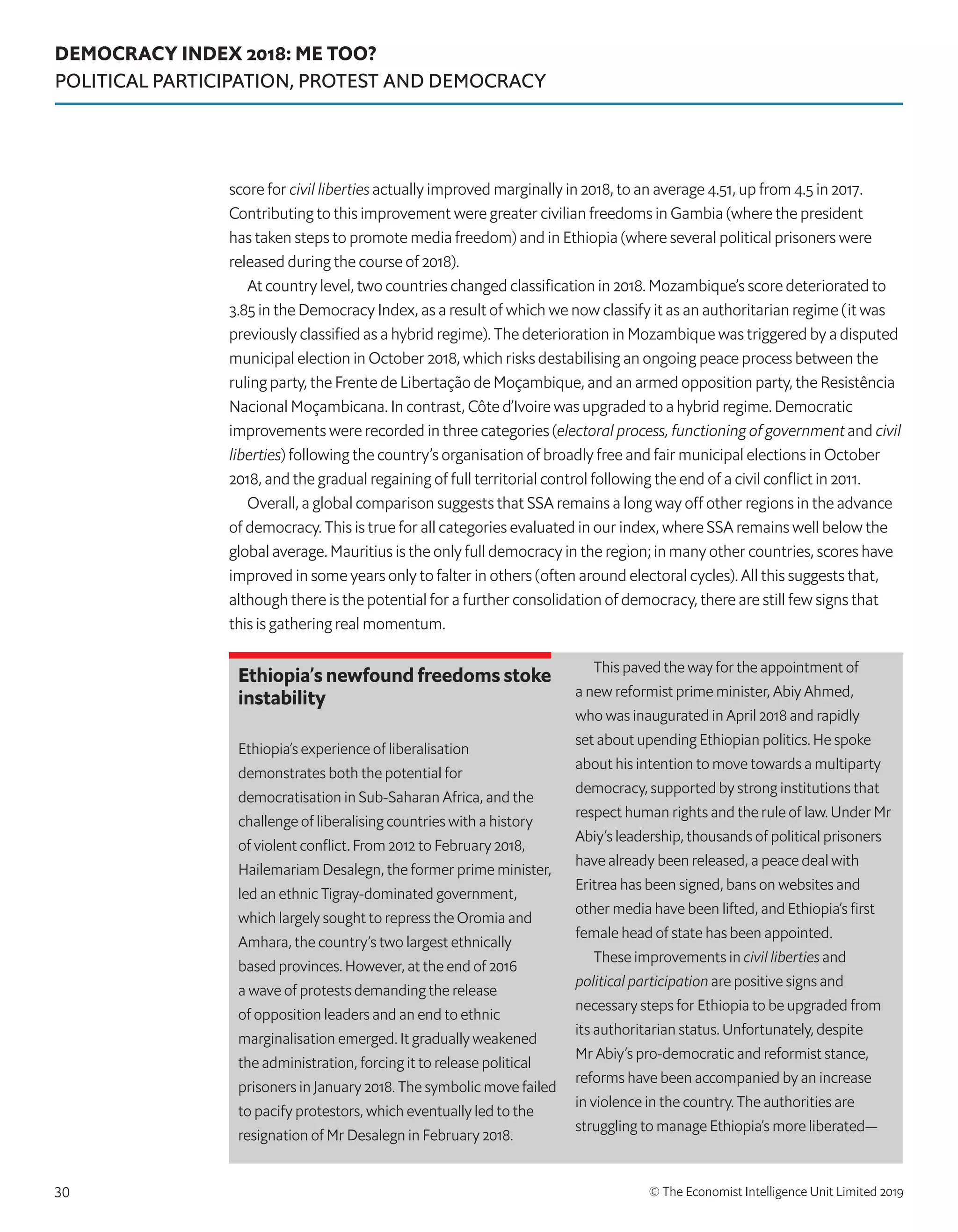

This document provides an overview and analysis of the Economist Intelligence Unit's Democracy Index for 2018. Some key points:

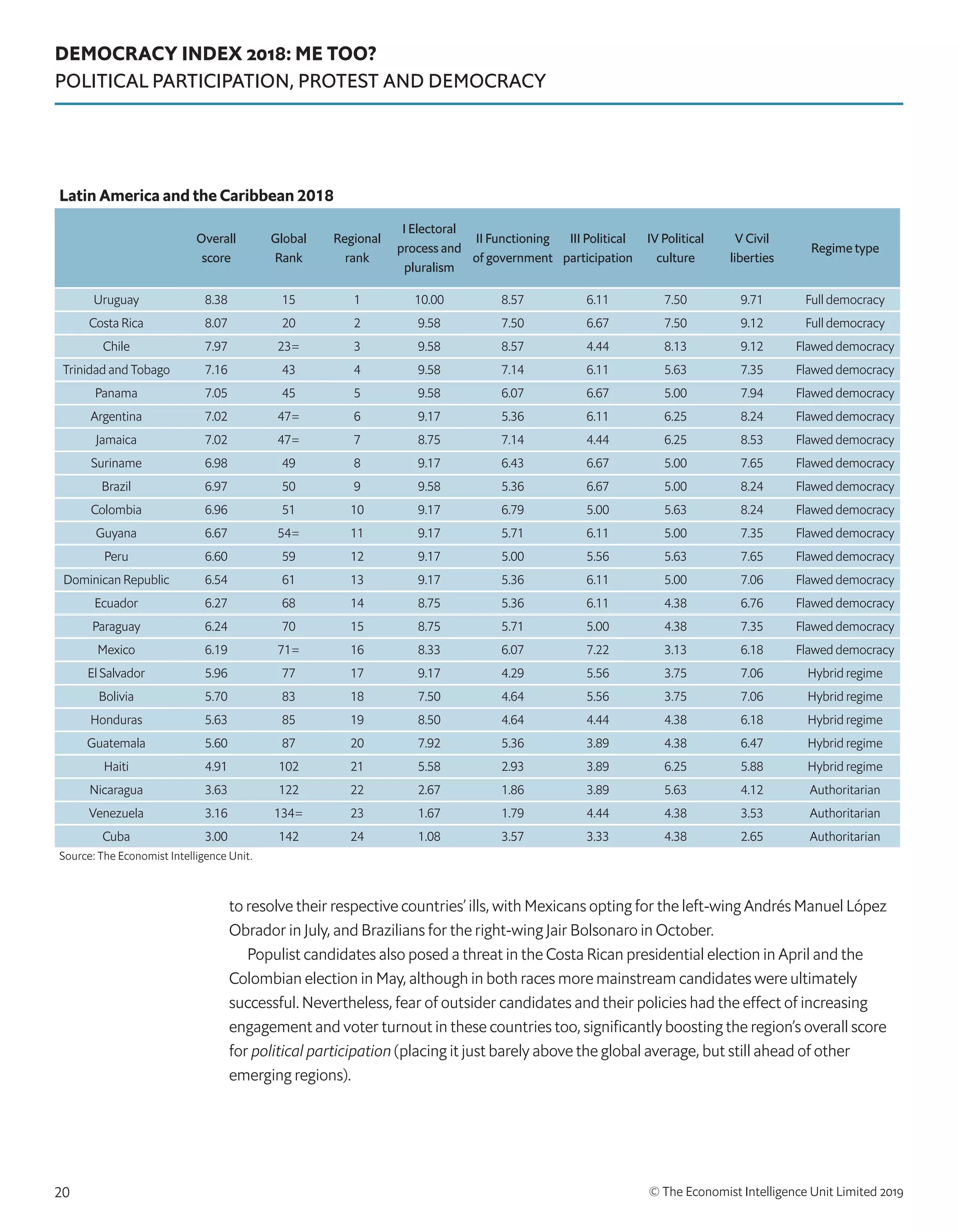

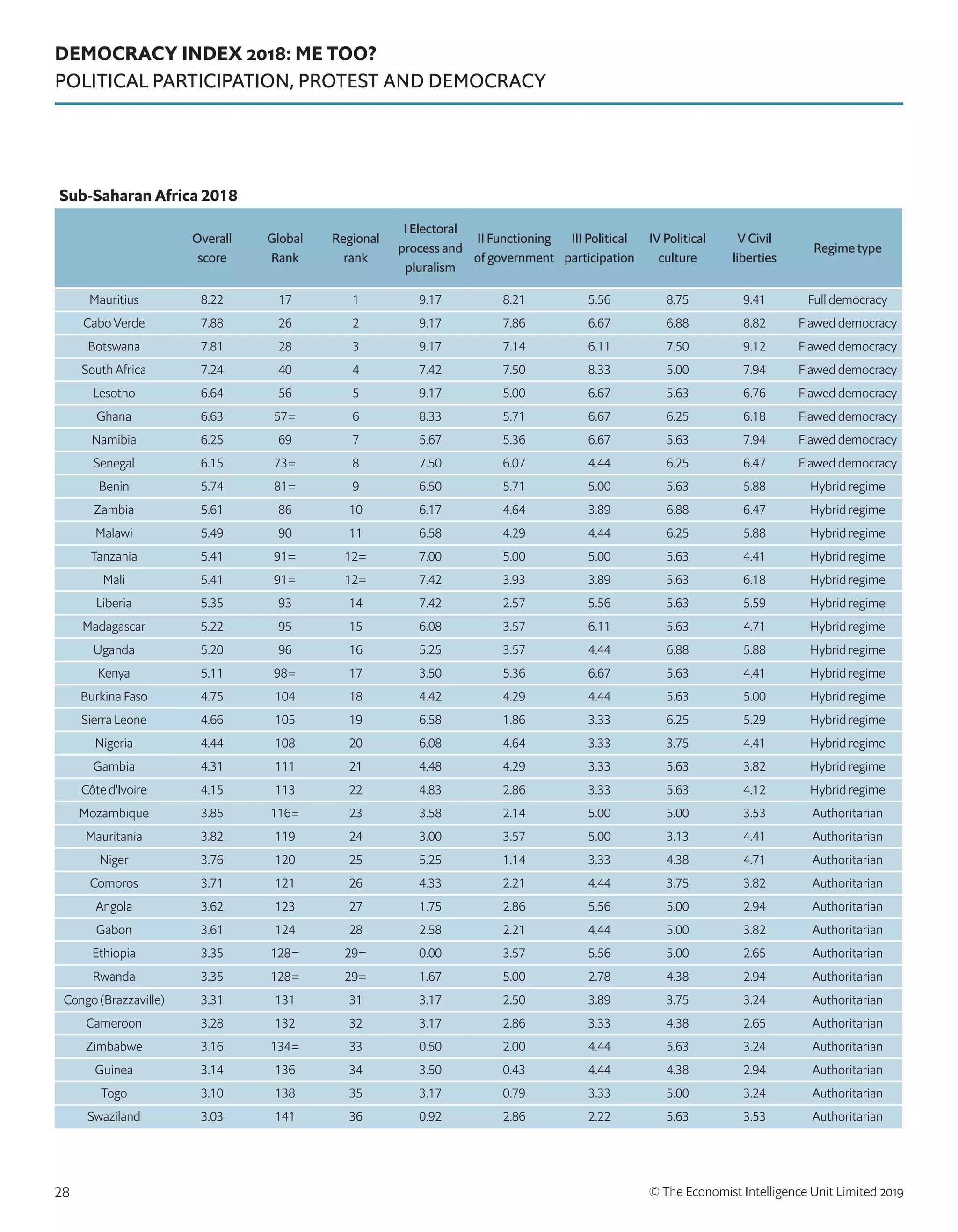

- The global score for democracy was stable for the first time in three years, though scores varied by region. One country improved from flawed to full democracy, while one declined from flawed to authoritarian.

- Political participation was the only category to improve globally in 2018, halting the decline seen in previous years. Protest and civic engagement increased around the world.

- Women's political participation made the most gains of any indicator over the past decade, with more countries adopting quotas to increase female representation.