1. Cybercrime costs the Dutch economy around €10 billion annually, or 1.5% of GDP, through value lost.

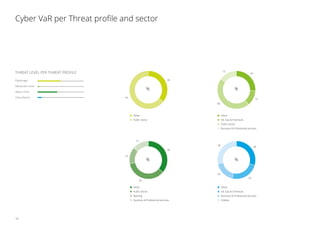

2. The report estimates potential "worst case" losses from cyber risks, known as Cyber Value at Risk (VaR), and finds it is typically 8 times higher than expected losses for large Dutch organizations.

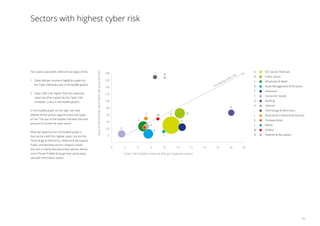

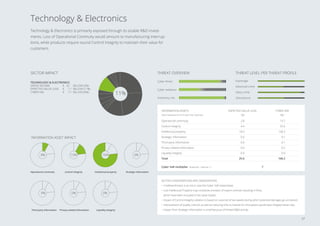

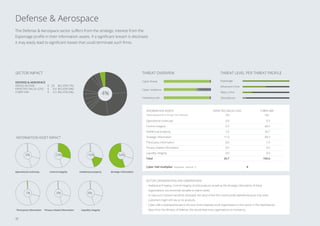

3. The sectors facing the highest cyber risks are identified as Technology & Electronics, Defense & Aerospace, Public, and Banking. Technology & Electronics and Defense & Aerospace face the highest Cyber VaR at around 17% of income.

![The Dutch state of cyber security

On average, the cyber security of organizations

in The Netherlands is relatively mature when

compared to countries with a similar threat

profile5

. Security is encoded in various laws and

regulations such as the “Wet Computercrimina-

liteit” and the “Wet Bescherming Persoonsgege-

vens”. Dutch policies are contained in the Natio-

nal Cyber Security Strategy as well as a Defense

Cyber Strategy, which are both implemented by

the National Cyber Security Center (NCSC). The

Netherlands has many international partner-

ships with European and global organizations.

It is hard to accurately determine the cyber

security of Dutch organizations based on public

data. Standardized metrics for performance

are lacking and not reported on, however,

useful metrics can be found through extensive

literature analysis. The annual Cyber Security

Assessment Netherlands (CSAN) by the NCSC

also provides useful figures. From our literature

study of over 250 scientific and professional

publications, we have inferred the maturity for

each sector, which we have validated with our

Deloitte sector experts as well as with our team

of around 180 security experts with hands-on

experience.

From this analysis, a couple of observations

stand out. First of all, cyber security maturity

levels tend to be higher for larger and heavily

regulated organizations. This effect is further

amplified when the organization in question is

multinational. Another important factor is expe-

rience with cyber threats. As a result we observe

that the Banking sector, the Oil, Gas Chemi-

cals sector, key components of Central Govern-

ment as well as the Defense Aerospace sector

are relatively mature. On the other hand, most

Small or Medium Enterprises (SMEs) as well as

organizations in the Education, Healthcare and

Utilities sectors have lower than average matu-

rity levels.

Organizations may influence each other in their

cyber maturity. For instance, all organizations

benefit from the relatively mature state of cyber

security of payments, leading to better Liquidity

Integrity for all organizations. This explains the

relatively low impact on Liquidity Integrity for all

organizations, despite high threat levels.

We distinguish four main layers of cyber security

controls: (I) prevention from entry (vulnerability

management, firewalls, etc.), (II) detection and

response (security monitoring and analytics,

incident response, etc.), (III) prevention of abuse

(e.g. encryption, data loss prevention, identity

and access management), and finally, (IV) reco-

very of losses (business continuity management,

crisis management, communications, legal, etc.).

Maturity in all four layers is required to obtain

optimal security. With the help of our quantifica-

tion methodology, optimizing cyber security for

individual organizations is also in reach.

The maturity level of cyber capabilities for an

organization is of key importance to seize the

opportunities of cyberspace while limiting the

impact of potential cyber incidents. Organizati-

ons with a higher level maturity take risks with

more confidence and are better able to innova-

te, or win and retain the trust of their custo-

mers. The efforts required for realizing a certain

maturity level do not exactly scale with the size

of the organization.

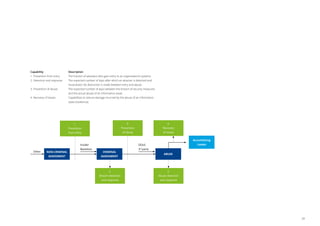

The cyber threat landscape

Overall, threat levels are apparent from cyber

threat intelligence reports. Furthermore, we

distinguish between threat profiles only to the

extent that they are attracted to other informati-

on assets or utilize different tactics.

Based on threat intelligence reports as well

as our own research, we make a distinction

between fast and slow attackers. The rationale

behind this is that sophisticated attackers often

make use of highly specialized methods combin-

ed with an incentive to go undetected for as long

as possible, while slowly accumulating abuse.

Less sophisticated attackers on the other hand

take advantage of known exploits and have

an incentive to act as fast as possible to take

advantage of the delay in the defender’s reac-

tion. These attackers are by nature also more

opportunistic, moving on to the next target with

the same method until they find a vulnerable

defender.

Another important characteristic that sets

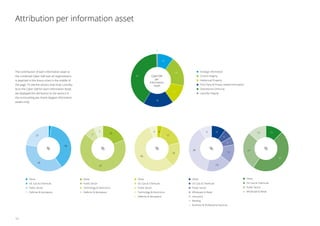

threat profiles apart is the type of information

assets that are targeted. Some attackers focus

on strategically important information assets,

while others aim at disruption of Operational

Continuity. Based on these insights, we defined

four threat profiles displayed in the table on the

next page.

5 Dutch Global Cybersecurity Index score 0.6765, ranked

6th according to ITU [54] and endorsed by the World

Economic Forum [8]. Also see: www2.deloitte.com/nl/

nl/pages/risk/articles/eu-voorzitter-loopt-op-dun-ijs-als-

cyber-security-gidsland.html.

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/34c03d5b-5c53-4149-8730-c1790cd1fc2a-160428152121/85/deloitte-nl-risk-cyber-value-at-Risk-in-the-Netherlands-10-320.jpg)

![This analysis of Cyber VaR for the Dutch economy

is based on the Cyber VaR concept that Deloitte

developed in collaboration with the World

Economic Forum. This chapter introduces the

model components, their workings and interre-

lations as well as the underlying assumptions.

Justification

To ensure quality and facilitate reproducibility,

the model builds on previous studies in the

field of cyber risk quantification and public data

as much as possible. The model uses a set of

logical relations to translate available data into

model parameters. The scarcity of suitable cyber

incident data is well known. Heuristic estimation

methods are used where needed to determi-

ne parameters when data or reports were not

available and have been demonstrated to be

surprisingly reliable [51].

The model draws from Deloitte’s insights from

handling cyber incidents for our clients as well

as experience gained in Deloitte’s Cyber Intelli-

gence Center. Furthermore, this report builds

on the expertise of Deloitte professionals in

areas ranging from cyber security, accounting to

legal and HR. We have also extensively involved

security experts at our clients, academia and

government to validate our assumptions and

methodology.

Dealing with uncertainty and Value at Risk

When dealing with risk, the expected impact

does not tell the full story. When a significant

event happens, the severity of the event for

the organization is a major factor in actual risk

assessments and decision making. The Cyber

VaR concept deals with exactly this combination

of expected, or average, impact and severity

in the ‘worst case’. More exactly, Cyber VaR

determines the impact that will annually not be

exceeded with a likelihood of about 95%. This

implies that once in 20 years, the Cyber VaR may

be exceeded with an unknown amount.

Inspired by its successful application in financial

risk management, we use the same approach of

(i) identifying the level of uncertainty around the

expected risk and (ii) the resulting impact this

uncertainty and ‘worst case’ impact have on an

organization’s value.

Due to imperfect data, this model is based on

estimates and assumptions. In the Cyber VaR

model these uncertainties are included by con-

sidering them as a contributor to risk in itself.

The meaning of this is simple: not knowing your

risk is a risk in and of itself.

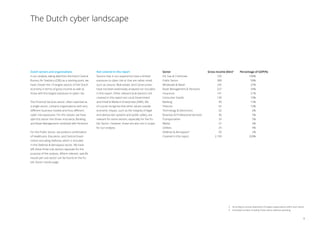

THREAT PROFILES

1. Espionage

2. Advanced Crime

3. Mass Crime

4. Disturbance

CYBER SECURITY

1. Prevention from entry

2. Detection and response

3. Prevention of abuse

4. Recovery of losses

INFORMATION ASSETS

1. Operational Continuity

2. Control Integrity

3. Intellectual Property

4. Strategic Information

5. Third Party Information

6. Privacy-related Information

7. Liquidity Integrity

Methodology and approach

“There was a statistician that

drowned crossing a river...

It was 3 feet deep on average.”

– A random statistician joke

35](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/34c03d5b-5c53-4149-8730-c1790cd1fc2a-160428152121/85/deloitte-nl-risk-cyber-value-at-Risk-in-the-Netherlands-35-320.jpg)

![Threat profiles

Each threat profile has its own level of maturity

in operating (i.e. sophistication level) that deter-

mines an organizations effective level of defense

against that threat profile. Based on the obser-

ved and recently modelled divide between slow

and fast attacks [56], we assign either a high or

a low sophistication level to the threat profiles.

Espionage and Advanced Crime demand a slow

approach to remain undetected and thus need

a high level of sophistication. In contrast, attac-

kers within the Mass Crime and Disturbance

profiles generally have a low sophistication and

act fast to optimize their gain. Although typical

attacks can differ slightly from these assumpti-

ons, in general attacks can be attributed to one

of these profiles.

Given the sophistication level of an attacker and

its corresponding abuse rate (slow or fast), the

total threat activity per type of information asset

is calculated. The threat activity is then distri-

buted according to the relative value impact for

each information asset type. Simply put, this

value impact determines how many attacks of

a certain threat profile are carried out on the

seven information assets.

The value impact for each information asset is

determined per organization, based on business

considerations such as the average income per

sector, as well as taking into account historic

cases of claims and fines in case of abuse.

We make an exception for the Espionage threat

profile. Since this type of attacker is interested

in information assets that are of strategic value

to them, the attractivity of these assets may far

exceed the actual value an information asset

has to the targeted organization.

For instance, Strategic Information, Intellectual

Property and Control Integrity within the De-

fense Aerospace sector are highly attractive

to attackers that fit into the Espionage threat

profile.

Information assets

In order to determine the value impact an infor-

mation asset has on an organization in case of

abuse, a single question needs to be answered:

what would the financial impact be in the event

that the information asset would be exploited in

its entirety?

For this purpose, we distinguish two factors: va-

lue impact in the form of reduced profits (either

directly or in the future due to loss of sales) and

costs due to claims by third parties, individu-

als and fines imposed by domestic or foreign

regulators.

With the recent developments in privacy regula-

tions and export controls these claims and fines

can be substantial.

The direct value impact calculation differs per

information asset, but generally consists of com-

ponents based on yearly income, equity value

and/or cash liquidity. We consider these factors

in different quantities per organization depen-

ding on the sector or by using publicly available

information on an organization.

Cyber defense capabilities

Based on historic events and sector specifics,

the capabilities of an organization to prevent

abuse of information assets by a certain threat

profile is different. These defensive capabilities

are divided into four cyber defense capabilities

related to the attack-defense process: “pre-

vention from entry”, “detection and response”,

“prevention of abuse” and “recovery of losses”.

37](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/34c03d5b-5c53-4149-8730-c1790cd1fc2a-160428152121/85/deloitte-nl-risk-cyber-value-at-Risk-in-the-Netherlands-37-320.jpg)