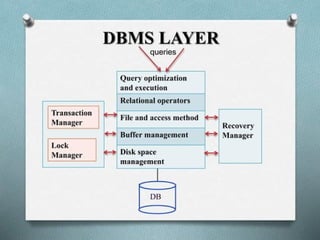

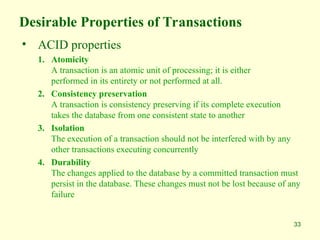

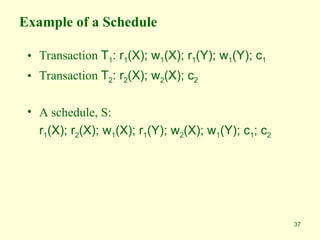

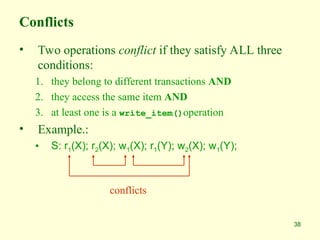

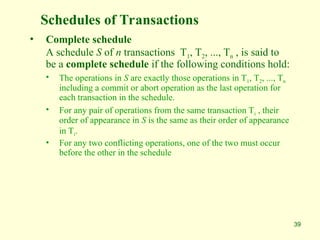

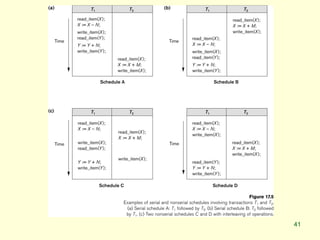

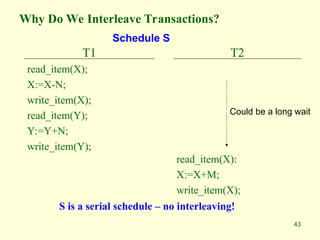

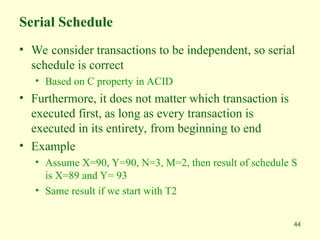

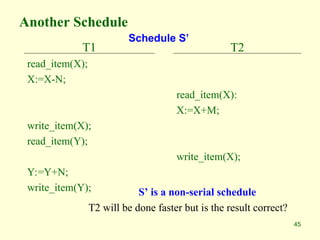

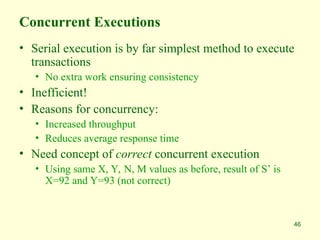

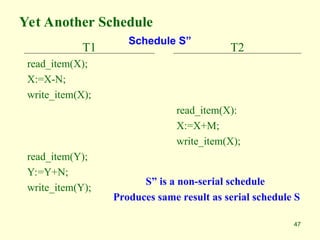

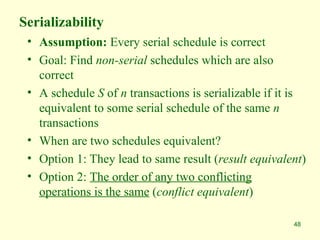

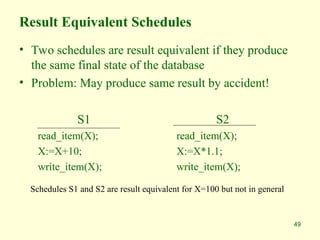

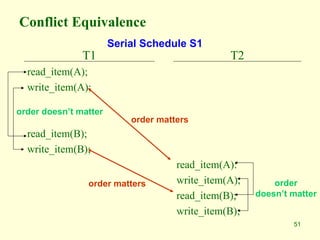

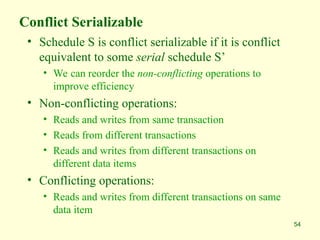

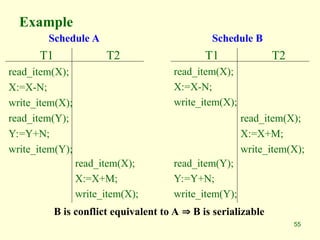

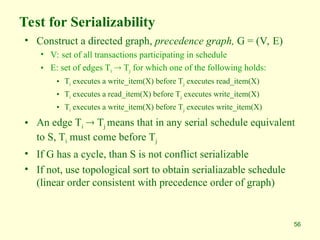

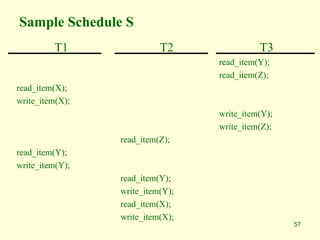

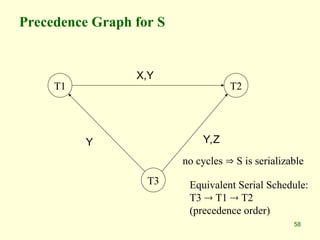

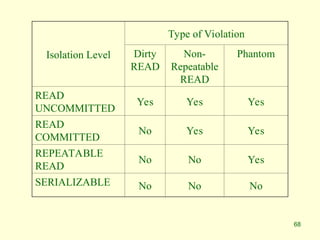

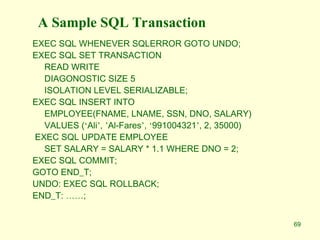

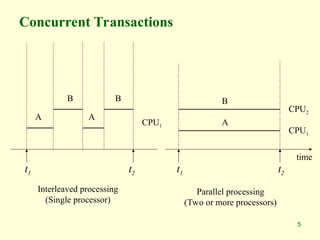

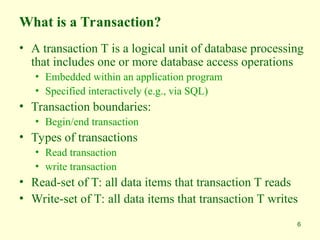

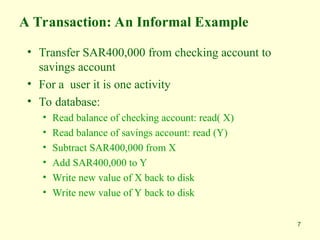

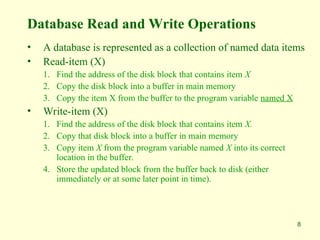

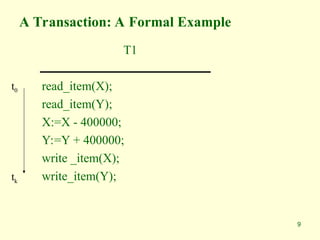

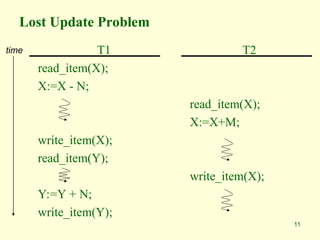

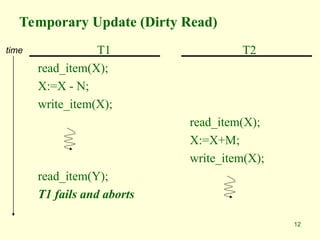

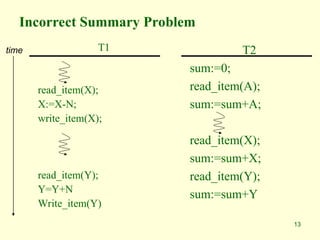

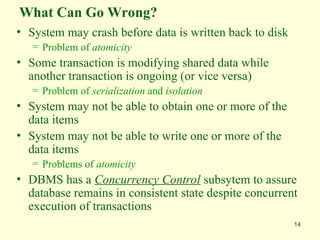

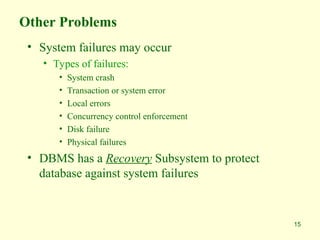

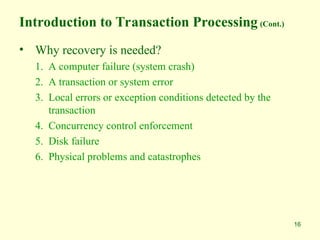

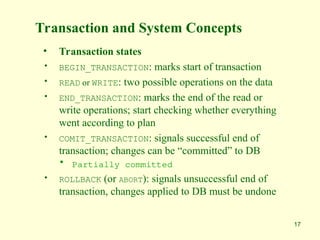

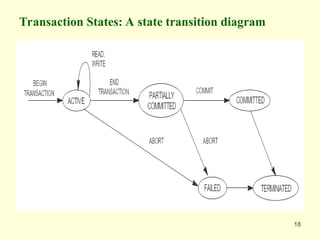

This document provides an introduction to transaction processing concepts, discussing essential components like transactions, their properties (ACID), concurrency, and recovery mechanisms. It emphasizes the need for concurrency control in multi-user database systems to prevent issues like lost updates and dirty reads. Additionally, it covers the importance of serializability in scheduling transactions to ensure consistent database states.

![19

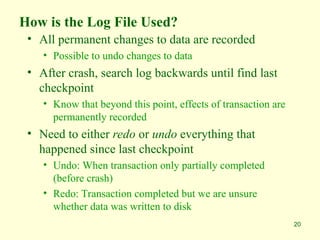

The System Log

• Transaction –id

• System log

• Multiple record-type file

• Log is kept on disk

• Periodically backed up

• Log records

1. [start_transaction, T]

2. [write_item, T,X,old_value,new_value]:

3. [read_item, T,X]

4. [commit,T]

5. [abort,T]

6. [checkpoint]

• Commit point of a transaction](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dbmsciitch8-240827102534-a8e3af45/85/DBMS-CIIT-Ch8-pptasddddddddddddddddddddd-19-320.jpg)