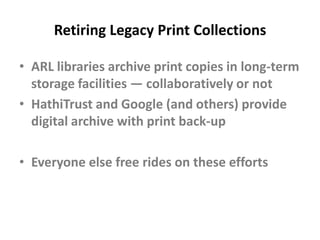

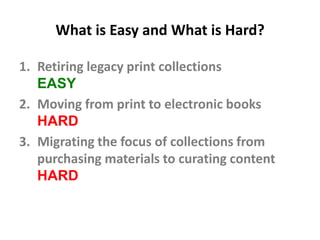

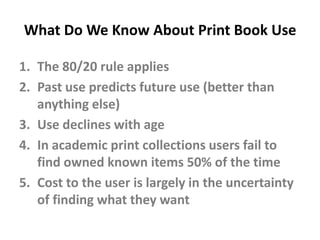

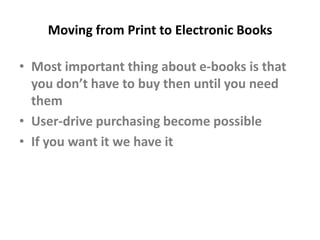

The document discusses collections, likely referring to the process or concept of gathering items or data systematically. It may cover various types of collections, their purposes, and their significance. Specific details about the methodology or examples are not provided.