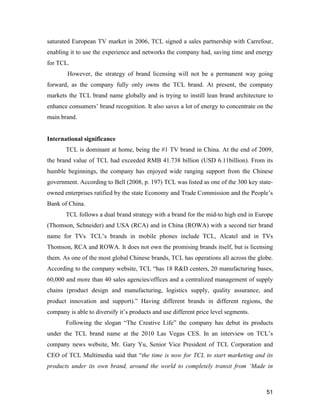

The document is a thesis written by Andras Bodrog in 2010 for the Faculty of Business Administration at Corvinus University of Budapest. It examines the internationalization of Chinese technology firms and the role of the Chinese government in supporting this process.

The thesis contains three main hypotheses: 1) Chinese tech firms' internationalization is best explained by behavioral internationalization theories, particularly the stages model. 2) China needs to develop indigenous innovation to reduce reliance on foreign technology and foster domestic growth. 3) The Chinese government actively supports the technology sector and firms' going global through policy programs and funding to increase China's competitiveness.

The thesis will explore internationalization theories, China's economic reforms and policies supporting the technology sector

![45

To become the top computer company, the management opted to diversify the

products and initially focus on the Chinese market. After carving out a large market

share at home, problems appeared: increasing competition from foreign companies (Dell,

HP), saturation of the PC market in China’s bigger cities. Lenovo was forced to seek

additional business opportunities in smaller and medium cities, in non-PC segments, and

eventually in international markets (Bell, 2008). The current domestic strength and

outperforming of foreign computer firms in China is due to Lenovo’s initial focus on the

Chinese market and the strong distribution networks the company created in smaller

cities.

Lenovo’s first abroad ventures were in Hong Kong, as a listed company to set up

distribution centers to serve the Chinese market. Real global expansion started after the

acquisition of IBM’s PC division in 2005. With the merger, the company gained IBM’s

customers and businesses in more than 160 countries becoming the 3rd

largest global

computer firm after Dell and HP. Yang Yuanqing, then chairman of the new Lenovo,

stated “[…] the transaction […] constitutes a new era of the international PC industry”

(Lenovo Group 2005). Lenovo’s founders’ aim was to make the company into a Fortune

500 firm and have a global brand name. Motivators, such as exploiting new markets,

escaping home market saturation and computer firms’ internationalization tendency

pushed Lenovo to globalize. In addition, Lenovo hired foreign trained managers who

could help bridge the cultural and managerial gap of international markets15

.

Since the global downturn, Lenovo has turned back to it’s roots and is again

China-centric. China accounted for 48% of the company's revenue for the first half of

2009. In the most recent quarter, China accounted for 47% of sales, the company said. At

the time of the IBM acquisition, the China business was 37% of sales (Businessweek,

2010).

Table 4: Internationalization of Lenovo

Important steps along the road to an international brand name creation:

2001 - Legend successfully spins off Digital China Co. Ltd., which is separately listed on the

Hong Kong Stock Exchange.

2002 - Legend launches its first technological innovation convention, “Legend World 2002,”

which opens up Legend’s “Technology Era”.

15

This is a new move, as many other Chinese companies used home grown managers in their

international expansion. Lenovo’s success is in some part due to hiring foreign managers.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cheff-200403162301/85/Chinese-Tech-Companies-Going-Global-2010-45-320.jpg)

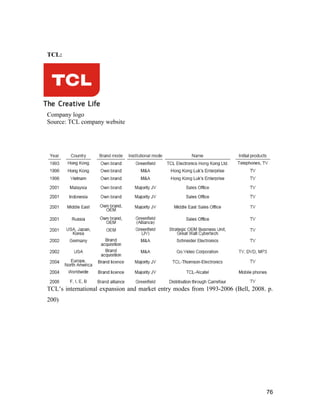

![77

Corporate structure:

Source: http://www.tcl.com/main_en/images/2010/01/08/528717037747.jpg

High Tech Indicators (HTI) Source:

http://www.tpac.gatech.edu/papers/HTI_China1_2008_jun10.pdf

“The HTI were developed as empirical manifestations of a conceptual model with four

“input” factors (c.f.,Roessner et al., 1992, for discussion of the conceptualization of these

leading indicators). Our website offers a number of papers and reports from over the

years, expounding on the indicators [//tpac.gatech.edu]. The HTI model posits that

technology-based competitiveness depends long term (i.e.,on the order of 15 years in the

future) on the conjunction of:

1) National Orientation to so compete (NO)

2) Socio-Economic infrastructure (SE)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cheff-200403162301/85/Chinese-Tech-Companies-Going-Global-2010-77-320.jpg)