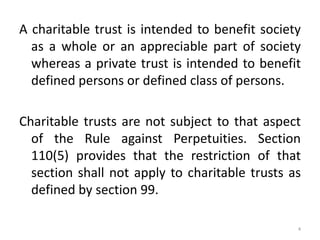

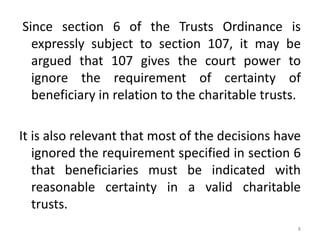

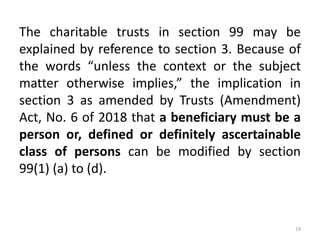

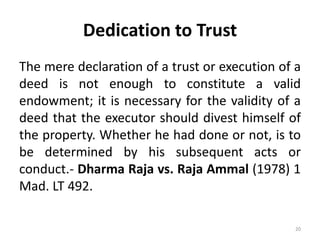

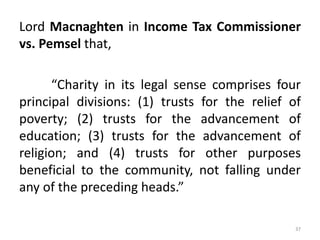

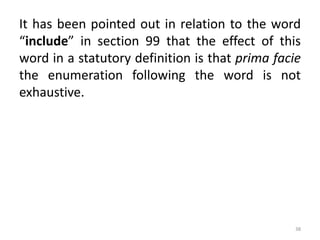

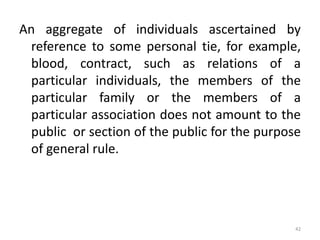

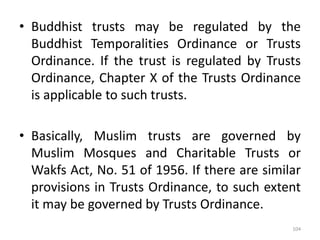

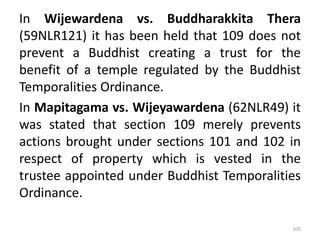

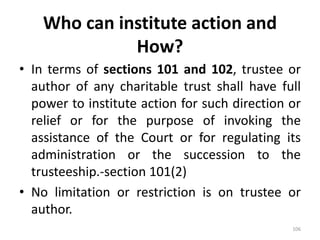

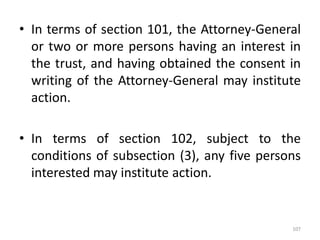

This document discusses the law of charitable trusts in Sri Lanka. It defines a charitable trust under Section 99 of the Trusts Ordinance as a trust for the benefit of the public or a section of the public for purposes such as relief of poverty, advancement of education, advancement of religion, or other purposes beneficial to mankind. Charitable trusts are not subject to the rule against perpetuities and can therefore last forever. The document outlines requirements for valid charitable trusts and exceptions made for charitable trusts under Sri Lankan law.

![Charities are not bound by this rule and may

therefore last forever. There are many charities

of considerable age which continue to operate.

Thus, where a gift is made of the income from a

particular fund to a charity in perpetuity, it will

never be possible to release the capital from the

fund: Re Levy [1960] Ch 346

5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/charitabletrustsvi-240129061744-9307f487/85/Charitable-Trusts-VI-pptx-5-320.jpg)

![The public benefit rule is very important aspect

in a trust to qualify as charitable trust.

Re Compton [1945] Ch. 123] where a trust for

the education of the descendants of three

named persons was held not to be a valid

charitable trust, because the beneficiaries

were defined by reference to a personal

relationship and the trust therefore lacked the

quality of a public trust; the trust was in

reality a family trust and not for the benefit of

a section of the public.

40](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/charitabletrustsvi-240129061744-9307f487/85/Charitable-Trusts-VI-pptx-40-320.jpg)

![Oppenheim v. Tobacco Securities Trust Co.

[1951 A.C. 297] where the trustees were

directed to apply funds in providing for the

education of children of employees or ex-

employees of British American Tobacco

company. The employees numbered over

110,000. A majority of House of Lords held

that although the group of persons indicated

was numerous, the nexus between them was

employment by a particular employer and this

trust did not satisfy the test of public benefit.

41](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/charitabletrustsvi-240129061744-9307f487/85/Charitable-Trusts-VI-pptx-41-320.jpg)

![On the other hand, if the trust is construed in

such a way as merely to grant a preference to

a limited class such as employees or relations

the trust will qualify as charitable trust.

In Re Koettgen’s Will Trust [1954] Ch 252 a

testatrix instructed that her residuary estate

should be held by her trustees ‘as a fund for

the promotion and furtherance of commercial

education’.

43](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/charitabletrustsvi-240129061744-9307f487/85/Charitable-Trusts-VI-pptx-43-320.jpg)

![Re Martin [1977] where a trust to establish a

home for old people, with a right for either or

both of the testator’s daughters to reside

there, was held not to be charitable.

Even though the requirement of public benefit is

must, it may differ from head to head

specified in section 99(1).

45](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/charitabletrustsvi-240129061744-9307f487/85/Charitable-Trusts-VI-pptx-45-320.jpg)

![Poverty may mean different things to different

people. Those who have been wealthy, but are

no longer so, may regard themselves as poor,

even though still comparatively well off.

Support for the relative approach is to be found

in the words of Sir Raymond Evershed in Re

Coulthurst [1951] Ch 661.

51](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/charitabletrustsvi-240129061744-9307f487/85/Charitable-Trusts-VI-pptx-51-320.jpg)

![Sir Raymond Evershed stated that “poverty, of

course, does not mean destitution... it [means]

persons who have to 'go short'... due regard being

had to their status in life and so forth".

Two points may be elucidated from this

statement. First, a person may in legal terms be

poor without being entirely without means. The

term is wide enough to embrace anyone who

does not have enough.

52](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/charitabletrustsvi-240129061744-9307f487/85/Charitable-Trusts-VI-pptx-52-320.jpg)

![Trusts for the relief of poverty form a major

exception to the usual rule as laid down in Re

Oppenheim. The courts have long accepted the

so-called ‘poor relation’ exception, whereby a

valid trust can be established for the relief of

poverty among the settlor’s poor relations. This

is valid so long as the class of beneficiaries is not

further restricted, for example, to a group of

named relations. The question was reviewed in

Dingle v Turner [1972] 1 All ER 878.

54](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/charitabletrustsvi-240129061744-9307f487/85/Charitable-Trusts-VI-pptx-54-320.jpg)

![In Dingle v Turner [1972] 1 All ER 878, a trust was

established for the benefit of poor employees of

Dingle & Co. At the time of the testator’s death,

the company employed over 600 persons.

Moreover, there were many ex-employees. The

court held that the trust was charitable.

The trusts for the relief of poverty requires a

different test from other forms of a charitable

trust which did not require a public benefit.

55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/charitabletrustsvi-240129061744-9307f487/85/Charitable-Trusts-VI-pptx-55-320.jpg)

![The essential difference between charitable and

private trusts in this area is between gifts for the

relief of poverty among poor people of a

particular description (which is charitable), and

gifts to particular persons, the relief of poverty

being the motive of the gift (which is not

charitable). A gift for the relief of poverty in a

particular class of relations could therefore be

charitable: in Re Scarisbrick’s Will Trust [1951] 1

All ER 822, the class named was ‘the relations of

my son and daughter’.

57](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/charitabletrustsvi-240129061744-9307f487/85/Charitable-Trusts-VI-pptx-57-320.jpg)

![It appears that even a selected group of

relations may qualify, in the light of Re

Segelman [1995] 1 All ER 676. In that case the

testator listed some, but not all, of his siblings,

and stated that they, together with their issue,

formed the class to be benefited.

Accordingly, there might be circumstances

where a narrow beneficial class, such as

employees of a firm or relations of an individual,

is a sufficient section of the public for relief of

poverty.

58](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/charitabletrustsvi-240129061744-9307f487/85/Charitable-Trusts-VI-pptx-58-320.jpg)

![Lord Hailsham, in IRC v McMullen [1980] 1 All

ER 884, said of education –

when applied to the young [it] is complex and

varied . . . It is a balanced and systematic

process of instruction, training and practice

containing spiritual, moral, mental and physical

elements.

61](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/charitabletrustsvi-240129061744-9307f487/85/Charitable-Trusts-VI-pptx-61-320.jpg)

![It may be assumed that anything which forms

part of the normal educational process and which

can be said to fall within that definition, will be

regarded as education and, that any trust for the

advancement of such things will be charitable,

subject to the requirement of public benefit.

The courts will reserve to themselves the right to

exclude things which they regard as harmful.

Harman J in Re Shaw [1957] 1 All ER 748 stated

that schools for prostitutes or pickpockets would

not be regarded as charitable.

62](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/charitabletrustsvi-240129061744-9307f487/85/Charitable-Trusts-VI-pptx-62-320.jpg)

![Attempts to disseminate political propaganda

under the guise of education have been

consistently rebuffed by the courts. Similarly,

educational charities will be restrained from using

their resources for political purposes. In Baldry v

Feintuck [1972] 2 All ER 81, Sussex University

Students’ Union, a registered charity, was

restrained from spending money on a campaign to

restore free school milk. Since this was an attempt

to challenge government policy, it was regarded

by the courts as political and not charitable.

63](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/charitabletrustsvi-240129061744-9307f487/85/Charitable-Trusts-VI-pptx-63-320.jpg)

![In McGovern v A-G [1981] 3 All ER 493, the

court stated –

(1) A trust for research will ordinarily qualify as a

charitable trust if, but only if (a) the subject

matter of the proposed research is a useful

object of study; (b) it is contemplated that the

knowledge acquired as a result of the research

will be disseminated to others; and (c) the trust

is for the benefit of the public, or a sufficiently

important section of the public.

64](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/charitabletrustsvi-240129061744-9307f487/85/Charitable-Trusts-VI-pptx-64-320.jpg)

![The House of Lords in Gilmour vs. Coats [1949] 1

All ER 848 held that the requirement of public

benefit is not satisfied, and a trust will fail as

charity, if the trust is created for the performance

of private ceremonies.

In Fernando vs. Sivasubramanium (61NLR241) a

trust was created by a Hindu testator, “desirous of

my soul’s attainment of salvation” for the

performance of religious ceremonies. Pulle J held

that the facts in two cases were very different and

therefore Gilmour case was not a relevant

authority.

72](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/charitabletrustsvi-240129061744-9307f487/85/Charitable-Trusts-VI-pptx-72-320.jpg)

![That purely private religious services are not

charitable has been confirmed in Re Le Cren

Clarke [1996] 1 All ER 715. The contrast

between this case and Re Hetherington [1989] 2

All ER 129 was that in Re Hetherington the

services could be conducted either in public or

in private and the judge was entitled to take a

benignant view of the gift and assume that they

would be held in public. In Re Le Cren Clarke, on

the other hand, evidence clearly indicated that…

73](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/charitabletrustsvi-240129061744-9307f487/85/Charitable-Trusts-VI-pptx-73-320.jpg)

![In Re Wedgewood ([1915] 1 Ch 113) A gift for

the benefit and protection of animals tends to

promote and encourage kindness towards them,

to discourage cruelty, and to ameliorate the

condition of brute creation, and thus to

stimulate humane and generous sentiments in

man towards the lower animals; and by these

means promote feelings of humanity and

morality generally, repress brutality, and thus

elevate the human race.

84](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/charitabletrustsvi-240129061744-9307f487/85/Charitable-Trusts-VI-pptx-84-320.jpg)

![An attempt to protect animals in isolation from

humans thus lacks the necessary benefit, as

emerged in Re Grove-Grady [1929] 1 Ch 557. In

this case, the testator left money to provide a

refuge or refuges for the preservation of all

animals, birds or other creatures not human . . .

So that, they shall be safe from molestation and

destruction by man’. Since man was entirely

excluded, he had no opportunity to be elevated

and so, there was no public benefit.

86](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/charitabletrustsvi-240129061744-9307f487/85/Charitable-Trusts-VI-pptx-86-320.jpg)

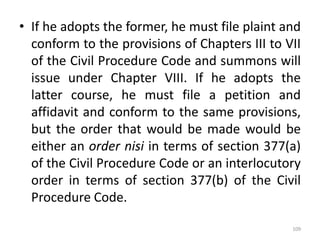

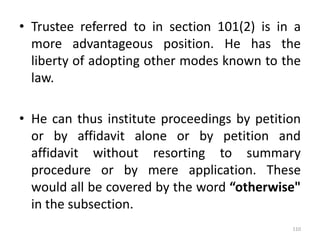

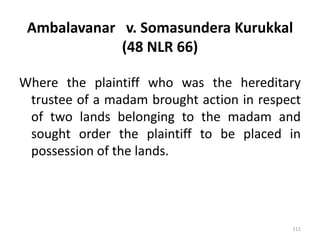

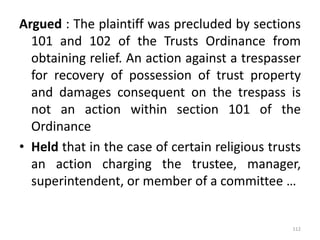

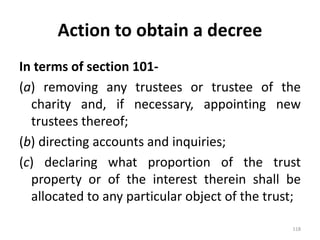

![Kurukkal v. Kurukkal

[1982] 2 SLR 562

• The court stated that section 101(2) permits a

trustee to apply to a court "by action or

otherwise".

• There are therefore many options open to a

trustee. He can bring an “action’’. Thus he can

institute an action adopting either “regular"

procedure or “summary” procedure. (Sec.7

Civil Procedure Code)…

108](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/charitabletrustsvi-240129061744-9307f487/85/Charitable-Trusts-VI-pptx-108-320.jpg)

![Murugeso v. Chellia

[58 NLR 463 at 467]

There is a sufficient indication of the

beneficiaries, since it is clear that any trust for

the benefit of a temple is in reality for the

benefit of the worshippers in that temple who

will, if necessary, be entitled to avail

themselves of the remedies provided for

beneficiaries in Chapter X of the Trusts

Ordinance.

114](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/charitabletrustsvi-240129061744-9307f487/85/Charitable-Trusts-VI-pptx-114-320.jpg)

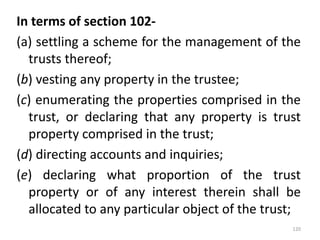

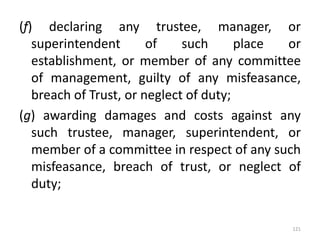

![Kurukkal v. Kurukkal

[1982] 2 SLR 562

The court stated that section101(1) deals with

all kinds of charitable trusts and empowers

two persons having an interest in the trust to

institute an action in court with the prior

permission of the Attorney-General. Section

102 deals with religious trusts and empowers

five persons interested in the trust to institute

an action in court provided …

129](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/charitabletrustsvi-240129061744-9307f487/85/Charitable-Trusts-VI-pptx-129-320.jpg)

![Ramesh and another v Chettiar

[2004] 1 SLR 355]

The plaintiff-petitioners instituted action against

the defendant who was a trustee of a Kovil

Trust. The court stated that it appears that the

plaintiffs have not submitted the plaint, to the

Divisional Secretary before filing it, to obtain a

certificate from the Divisional Secretary. ..

132](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/charitabletrustsvi-240129061744-9307f487/85/Charitable-Trusts-VI-pptx-132-320.jpg)

![Thiyagarajah and others v Gopalakrishnanath

and other [2007] 2 SLR 245]

If the plaintiffs have any complaint against the

defendants as trustees with regard to any

matter such as mismanagement, negligence,

breach of trust or removal of trustees, the

proper remedy is to seek the jurisdiction of

the District Court in terms of section 102 of

the Trusts Ordinance, and further a certificate

of the Divisional Secretary is imperative

under and in terms of section 102(3).

134](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/charitabletrustsvi-240129061744-9307f487/85/Charitable-Trusts-VI-pptx-134-320.jpg)

![Velautham v. Velauther

[1957] 61 NLR 203

An action under section 102(3) of the Trusts

Ordinance will not be entertained unless it

appears from the certificate issued by the

Divisional Secretary that a copy of the plaint

had been presented to him along with the

petition.

135](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/charitabletrustsvi-240129061744-9307f487/85/Charitable-Trusts-VI-pptx-135-320.jpg)