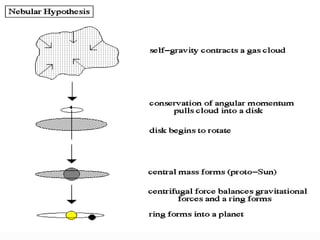

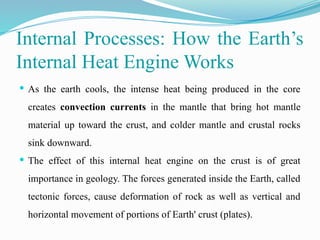

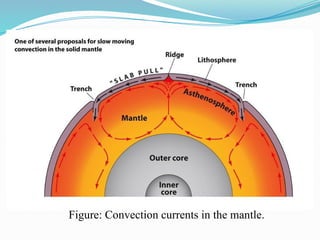

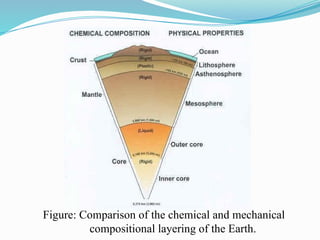

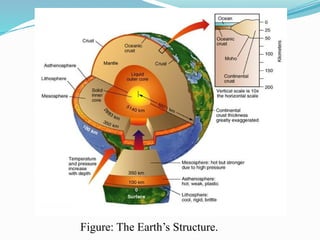

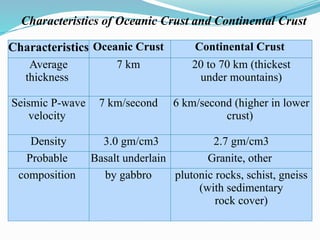

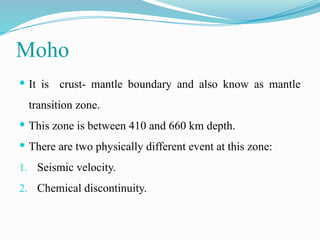

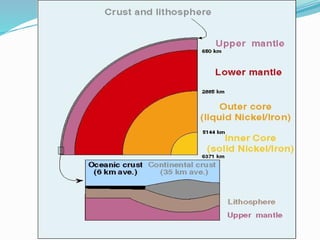

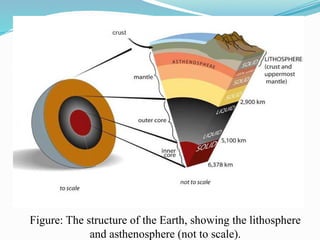

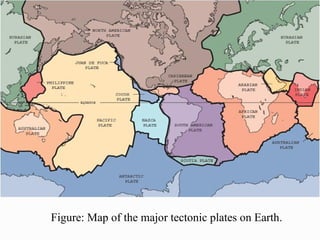

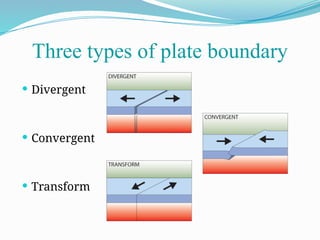

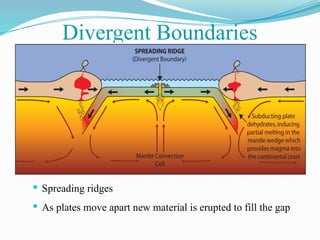

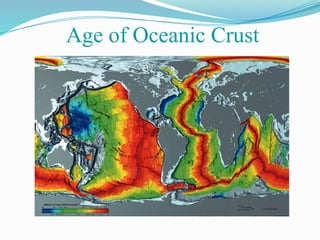

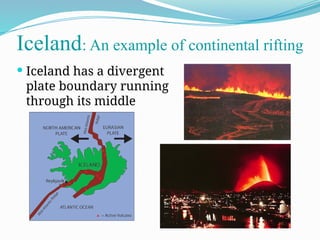

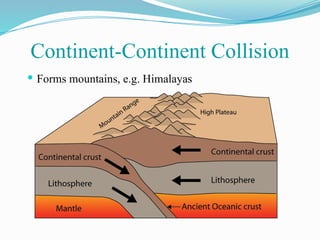

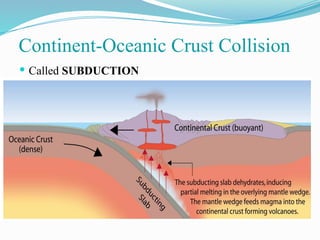

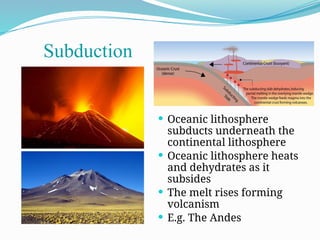

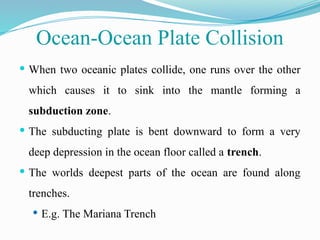

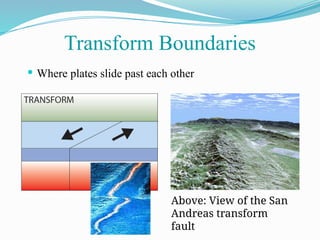

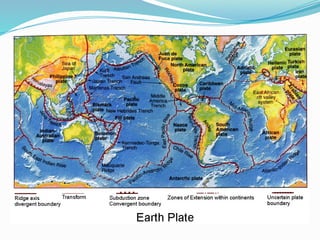

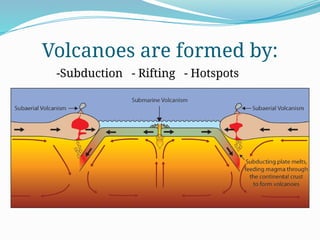

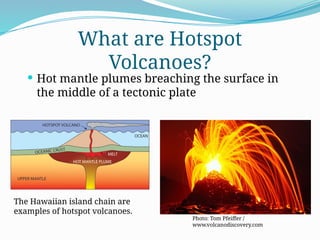

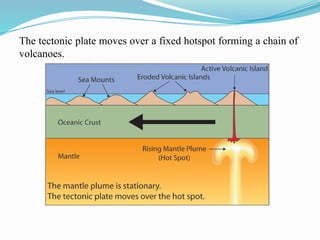

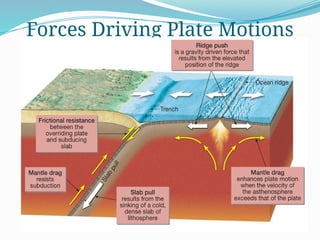

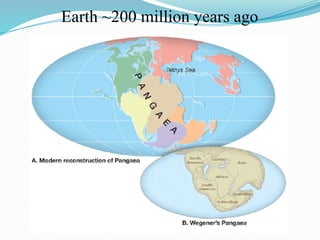

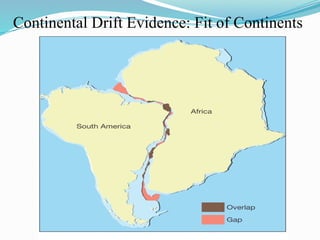

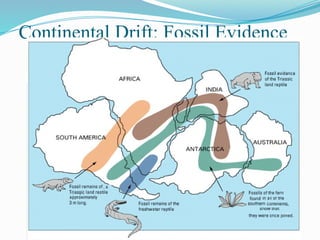

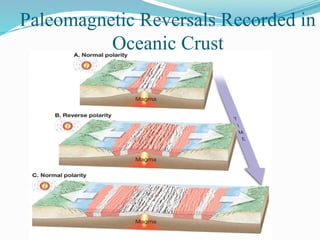

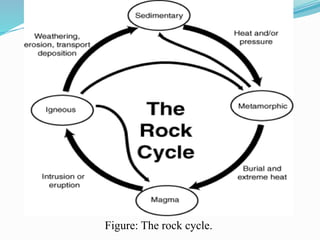

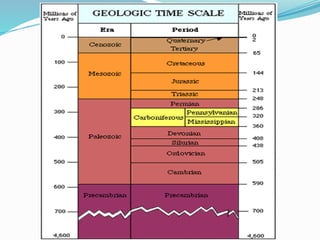

Geology is the study of the Earth, its materials, and the processes that shape it, divided into physical and historical geology. Key concepts include tectonic plates, the rock cycle, and the formation of Earth's layered structure, alongside the processes such as volcanism and erosion. The document details the theory of plate tectonics, the distinction between oceanic and continental crust, and the significance of geological time in understanding Earth's history.