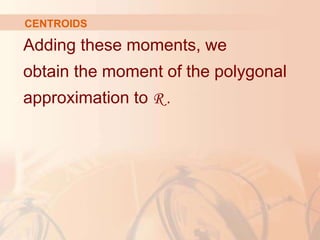

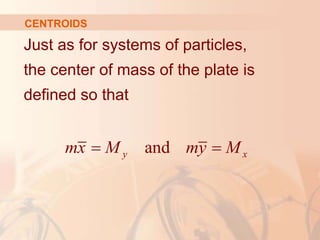

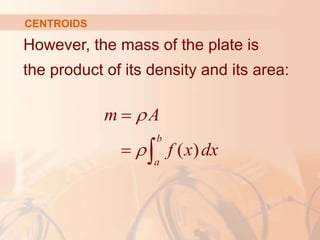

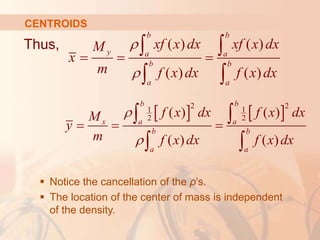

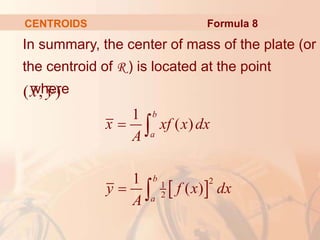

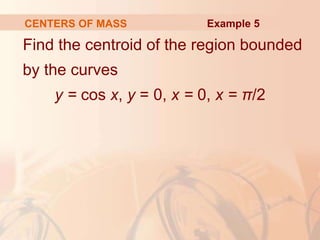

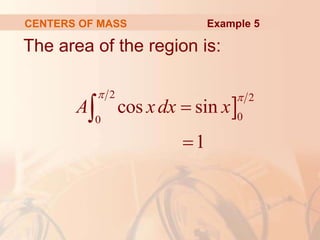

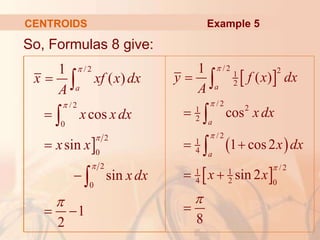

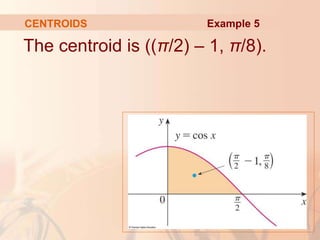

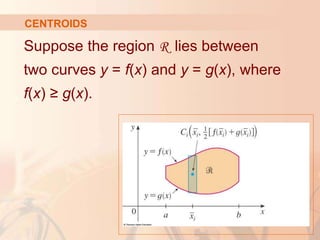

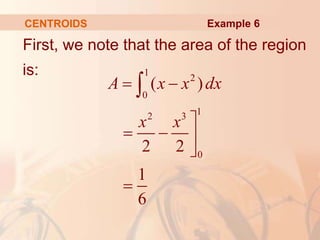

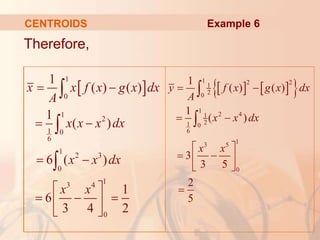

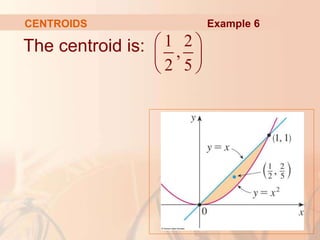

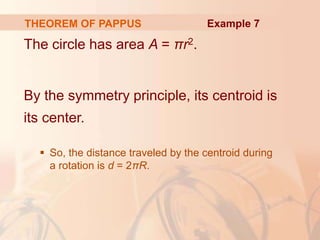

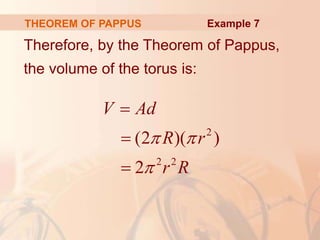

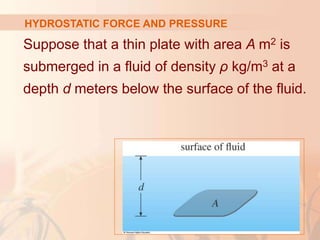

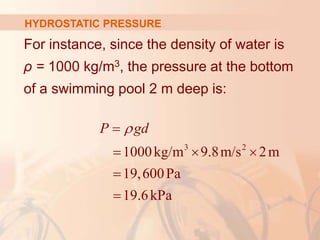

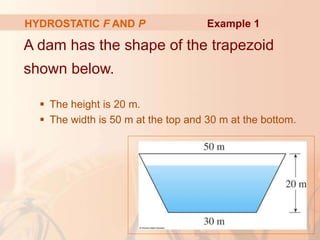

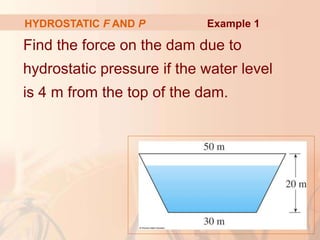

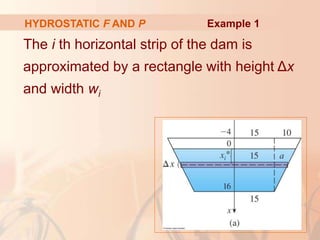

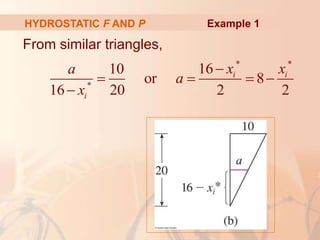

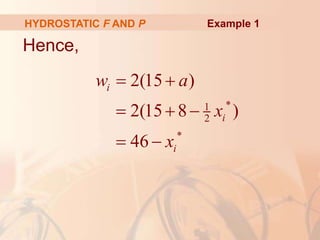

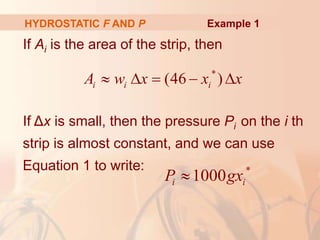

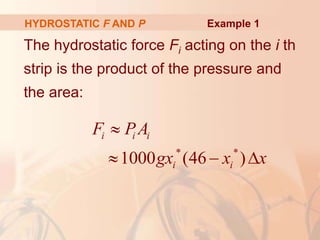

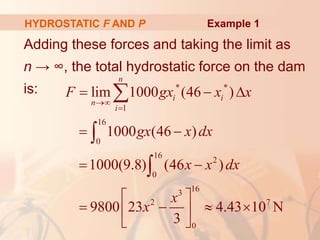

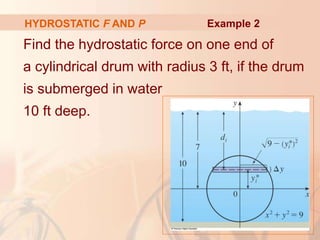

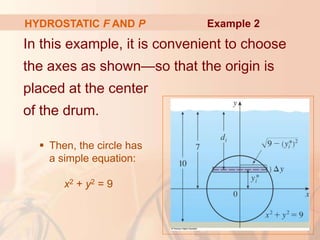

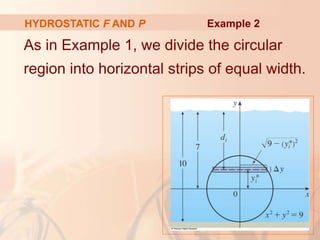

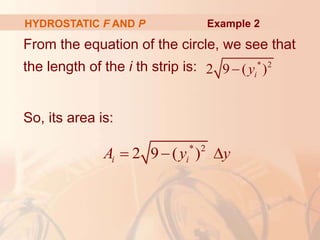

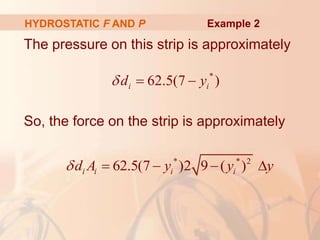

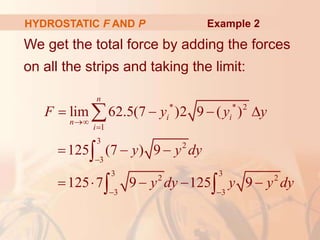

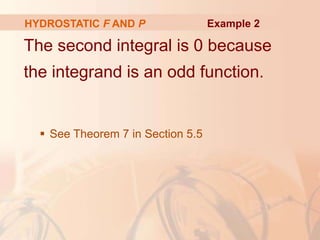

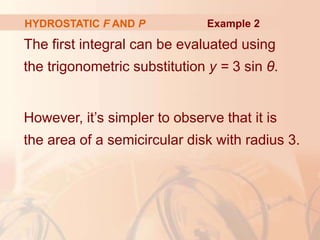

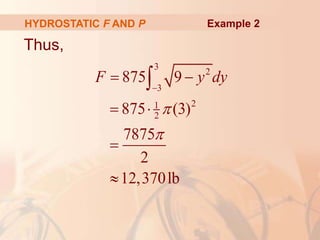

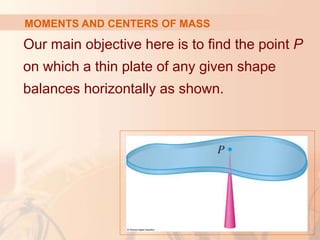

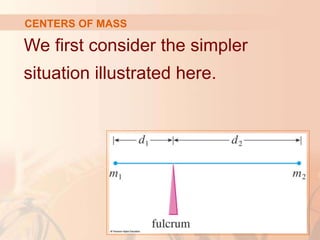

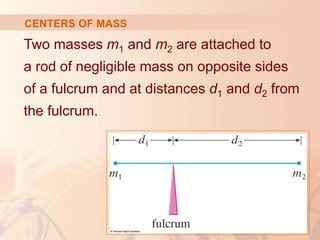

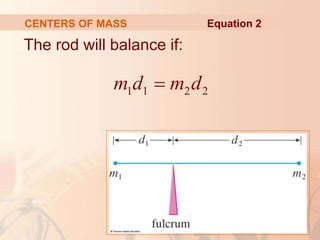

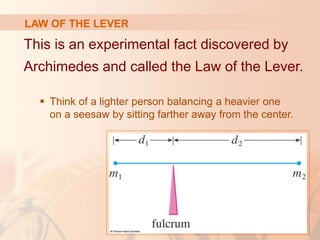

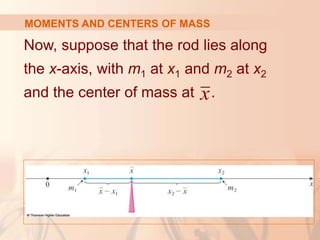

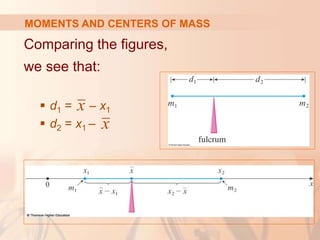

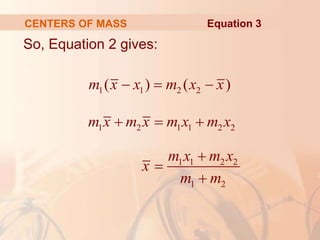

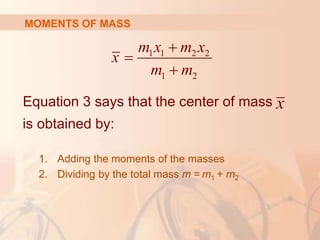

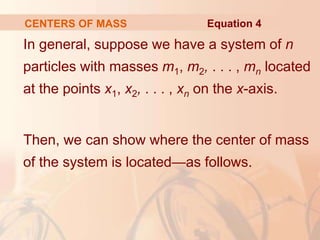

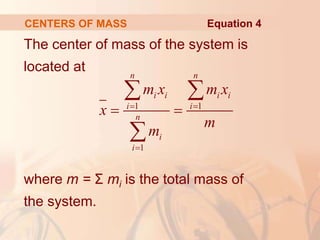

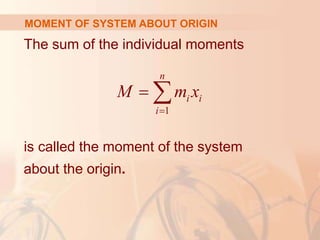

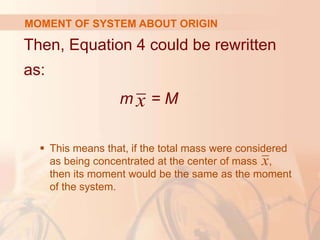

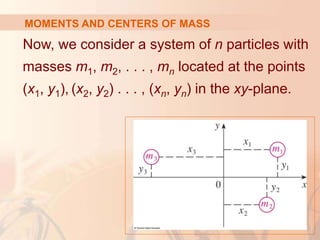

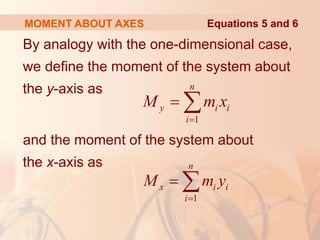

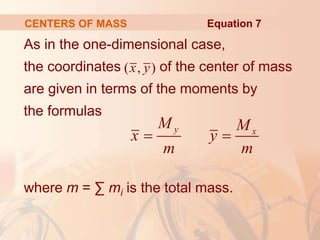

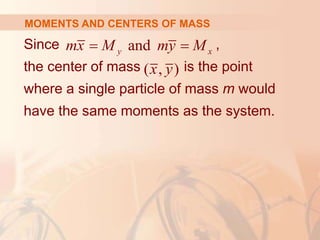

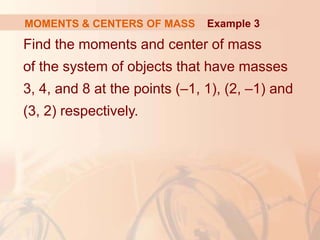

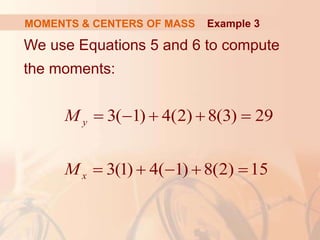

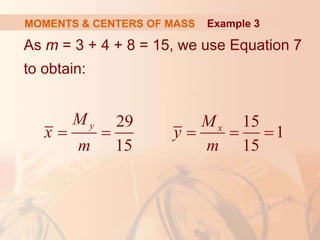

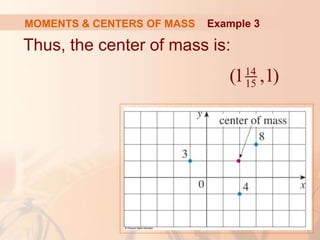

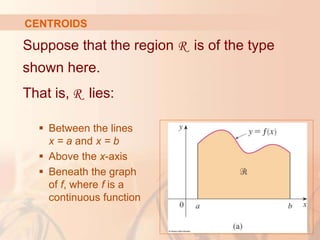

This document discusses applications of integral calculus to physics and engineering problems involving force, pressure, and centers of mass. It provides examples of using integrals to calculate the hydrostatic force on structures like dams and cylinders submerged in water. It also explains how to find the center of mass of an object or system of point masses by taking moments about axes and dividing by total mass. Formulas are given for calculating hydrostatic pressure, moments, and centers of mass in one and two dimensions.

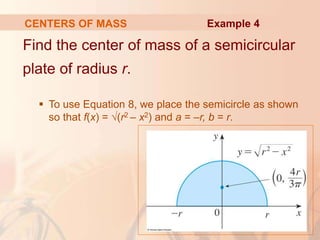

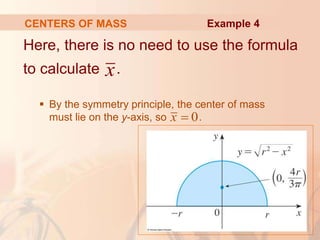

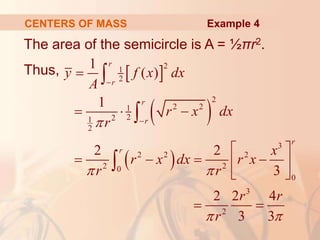

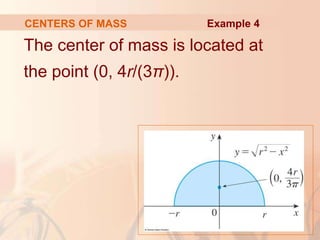

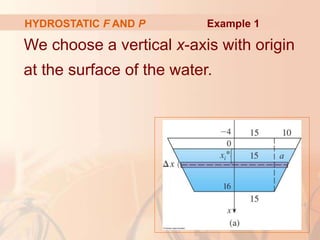

![The depth of the water is 16 m.

So, we divide the interval [0, 16] into subintervals

of equal length with endpoints xi.

We choose

xi* [xi–1, xi].

HYDROSTATIC F AND P Example 1

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chap8sec3-220829135656-7db0b0cd/85/Chap8_Sec3-ppt-17-320.jpg)

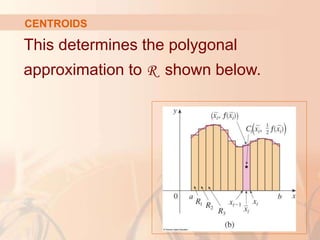

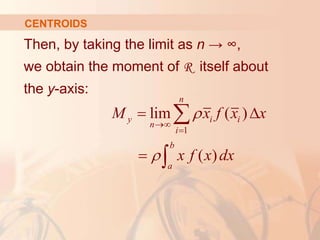

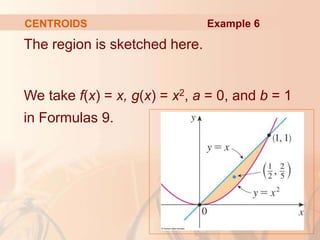

![We divide the interval [a, b] into n subintervals

with endpoints x0, x1, . . . , xn and equal width

∆x.

We choose the

sample point xi

* to

be the midpoint

of the i th

subinterval.

That is,

= (xi–1 + xi)/2

CENTROIDS

i

x

i

x](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chap8sec3-220829135656-7db0b0cd/85/Chap8_Sec3-ppt-63-320.jpg)