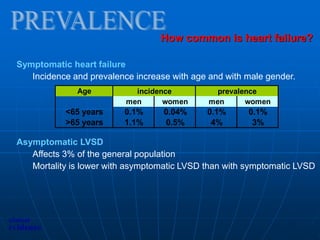

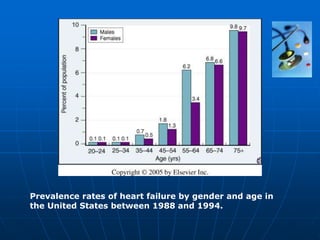

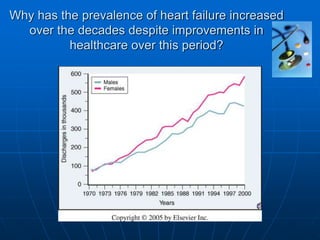

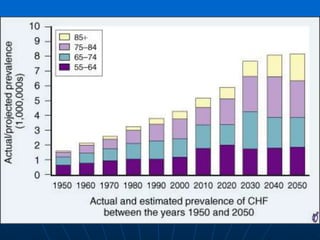

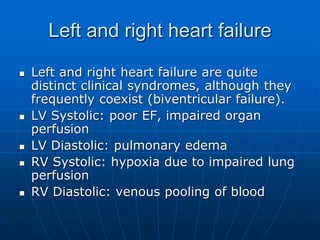

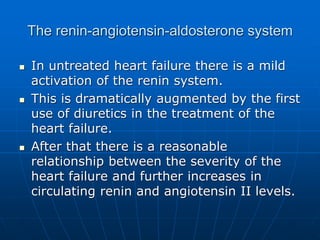

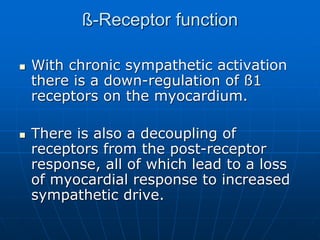

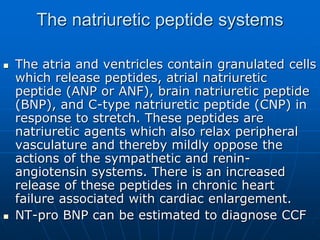

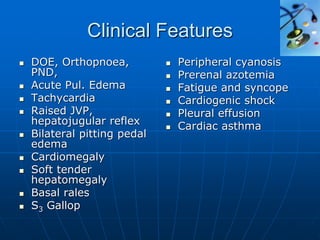

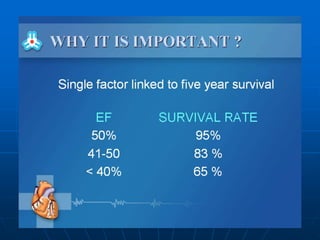

This document defines cardiac failure and heart failure, describes the types and causes, and discusses the pathophysiology, clinical features, investigations, and treatment. Heart failure is a clinical syndrome where the heart cannot pump enough blood to meet the body's needs, or can only do so with elevated filling pressures. It can be systolic or diastolic in nature. Common causes include ischemic heart disease, cardiomyopathy, valvular disease, and hypertension. Symptoms include breathlessness, fatigue, and fluid retention. Echocardiography, biomarkers like BNP, and cardiac imaging are used in diagnosis and assessment. Treatment aims to relieve symptoms, improve quality of life, and reduce mortality through medications, device therapies, and lifestyle changes.

![Reduced cardiac output (blood pumped in one minute)

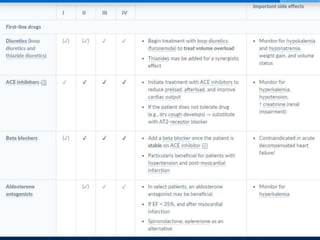

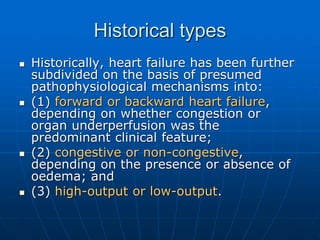

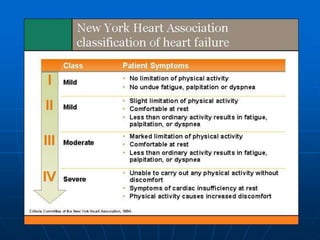

Heart failure is the clinical syndrome that develops when the heart

cannot maintain an adequate cardiac output, or can do so only at

the expense of an elevated filling pressure.

Impaired pump function

• systolic

left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) < 0.4 (40%)

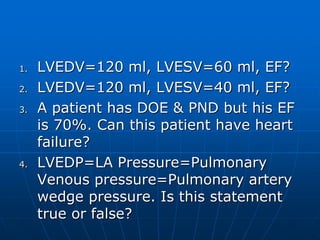

EF=[LVEDV-LVESV]/LVEDV

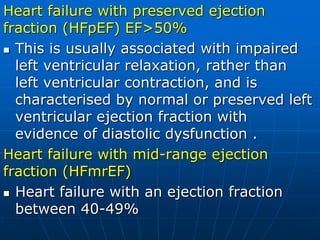

• diastolic

difficult to define & diagnose

1) clinical evidence of heart failure

2) minimal or no LVEF reduction

3) abnormal ventricular relaxation, filling, distensibility

or stiffness (difficult to standardise)

Characteristic symptoms

heart failure can be asymptomatic or associated with:

breathlessness, effort intolerance, fluid retention.

What is heart failure?

clinical

evidence](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cardiacfailuresem5-230115150607-00b5d922/85/Cardiac-Failure-Sem-5-pptx-2-320.jpg)

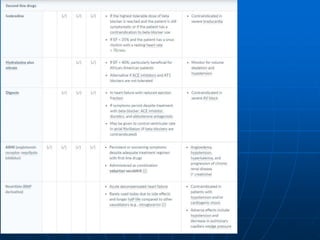

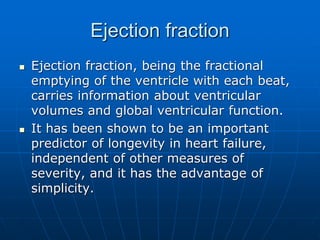

![ [LVEDV-LVESV]/LVEDV=EF

When EF<40%, Heart failure with

reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cardiacfailuresem5-230115150607-00b5d922/85/Cardiac-Failure-Sem-5-pptx-4-320.jpg)

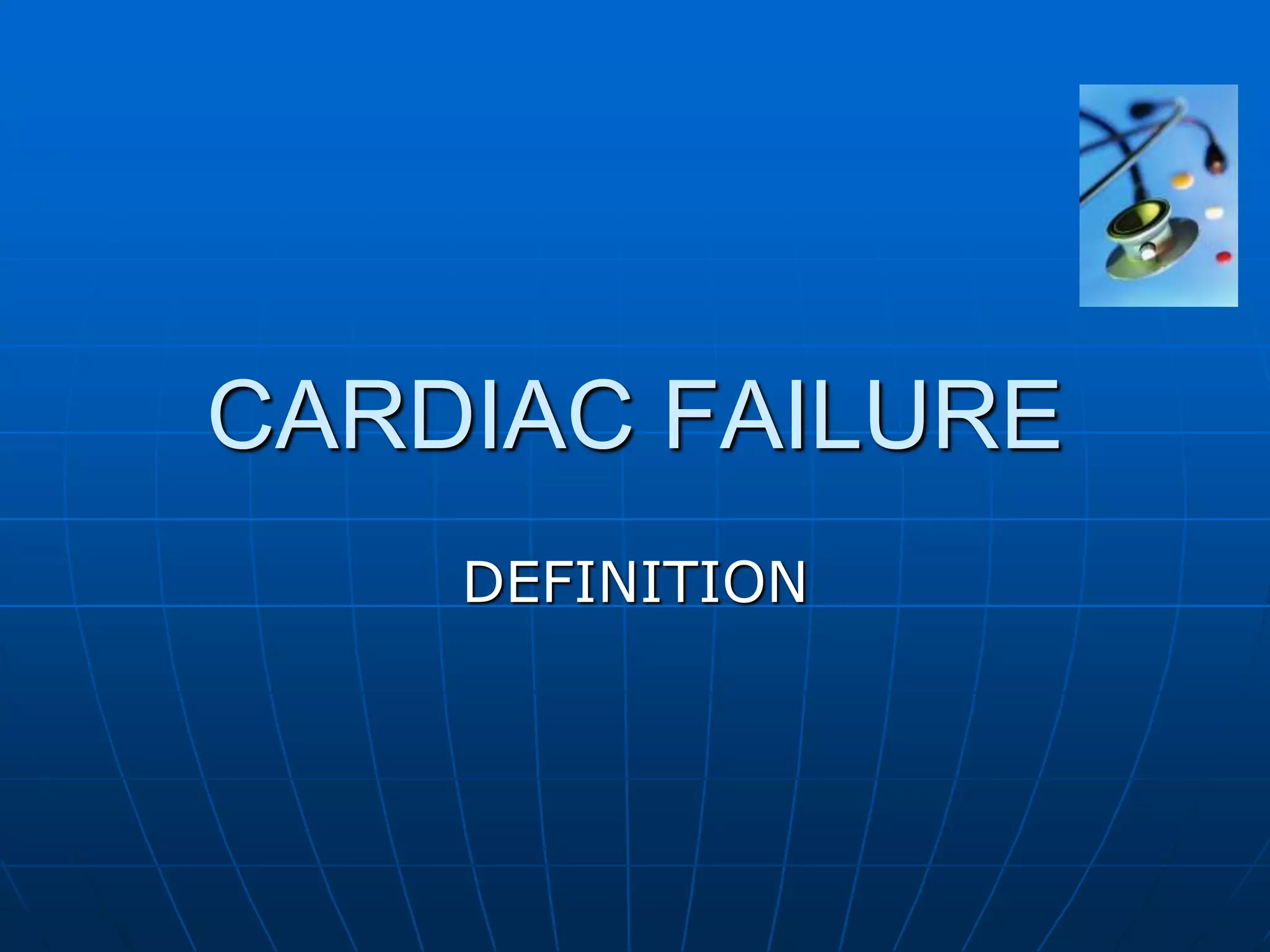

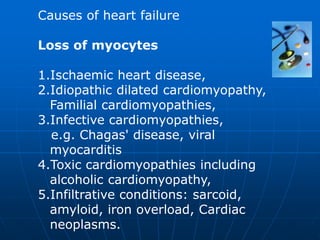

![• relieve symptoms

• improve quality of life

• reduce mortality and morbidity

• minimise adverse effects

• Functional capacity

- New York Heart Association scale

- standardised exercise testing

- 6 minute walk test

• Quality of life

questionnaires

• Mortality

• Adverse effects

[Proxy measures used only when clinical

outcomes are unavailable

- LVEF

- hospital readmission rates]

Aims

Measures

clinical

evidence](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cardiacfailuresem5-230115150607-00b5d922/85/Cardiac-Failure-Sem-5-pptx-42-320.jpg)