Bioprocess Engineering: Kinetics, Sustainability, and Reactor Design 3rd Edition Shijie Liu

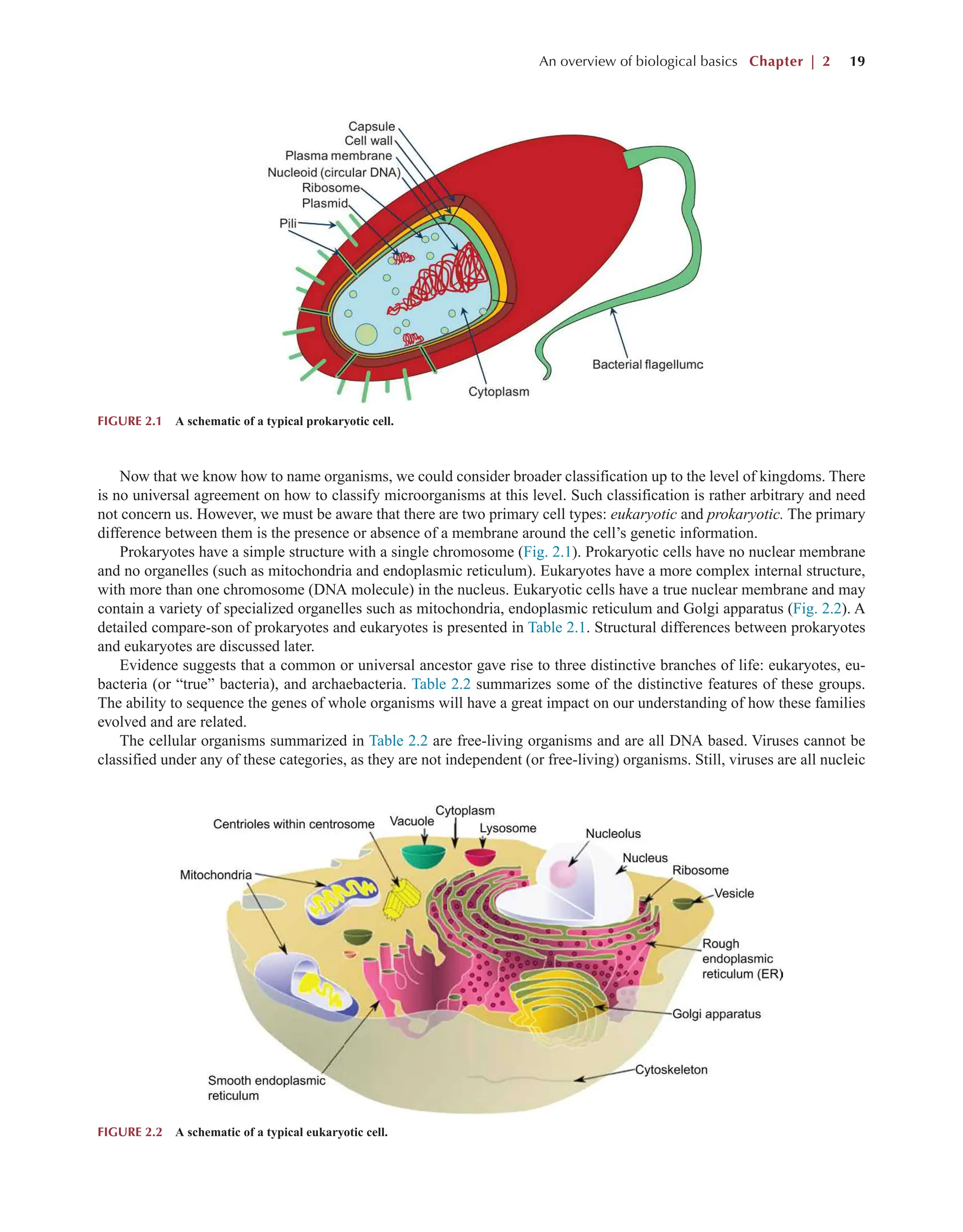

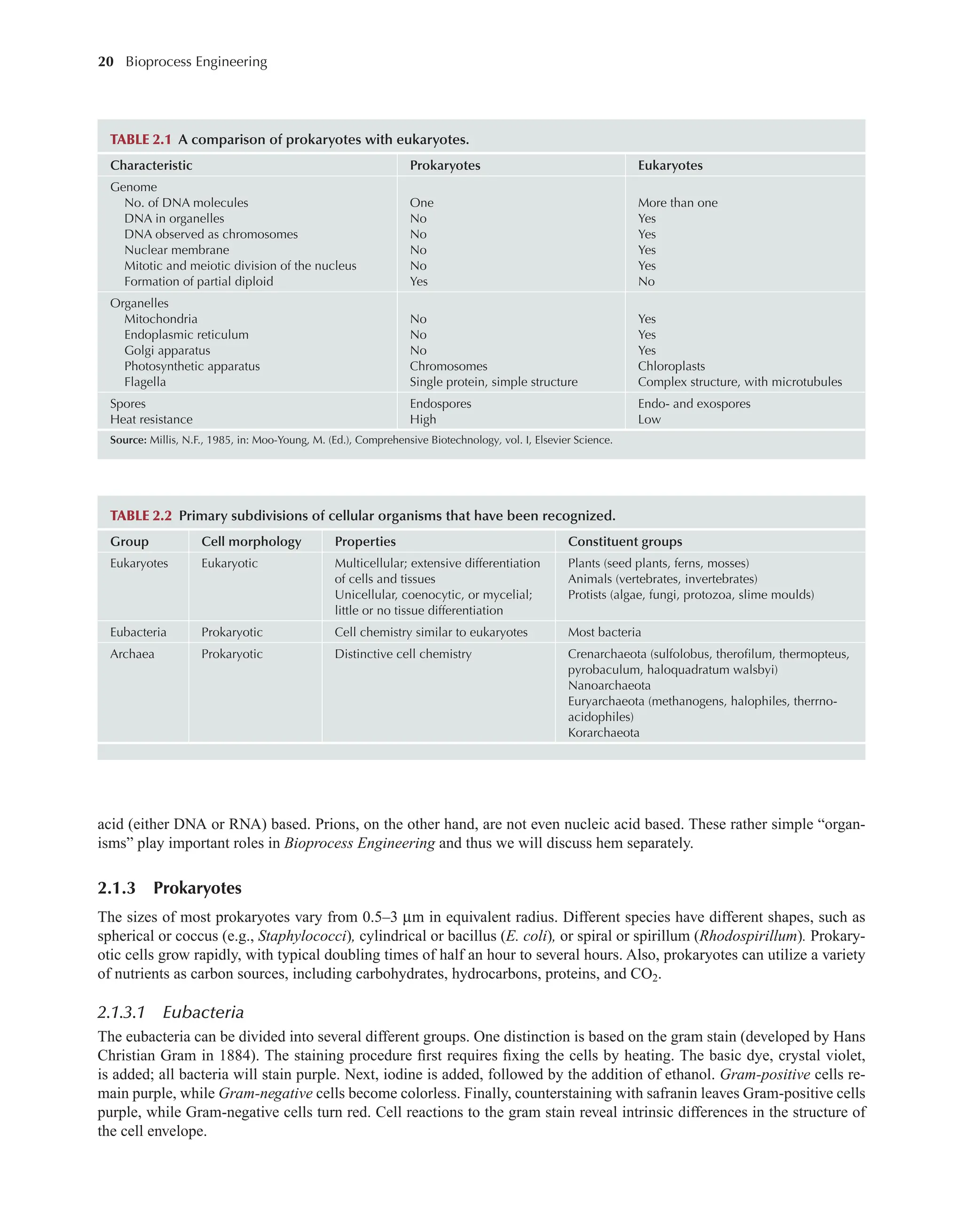

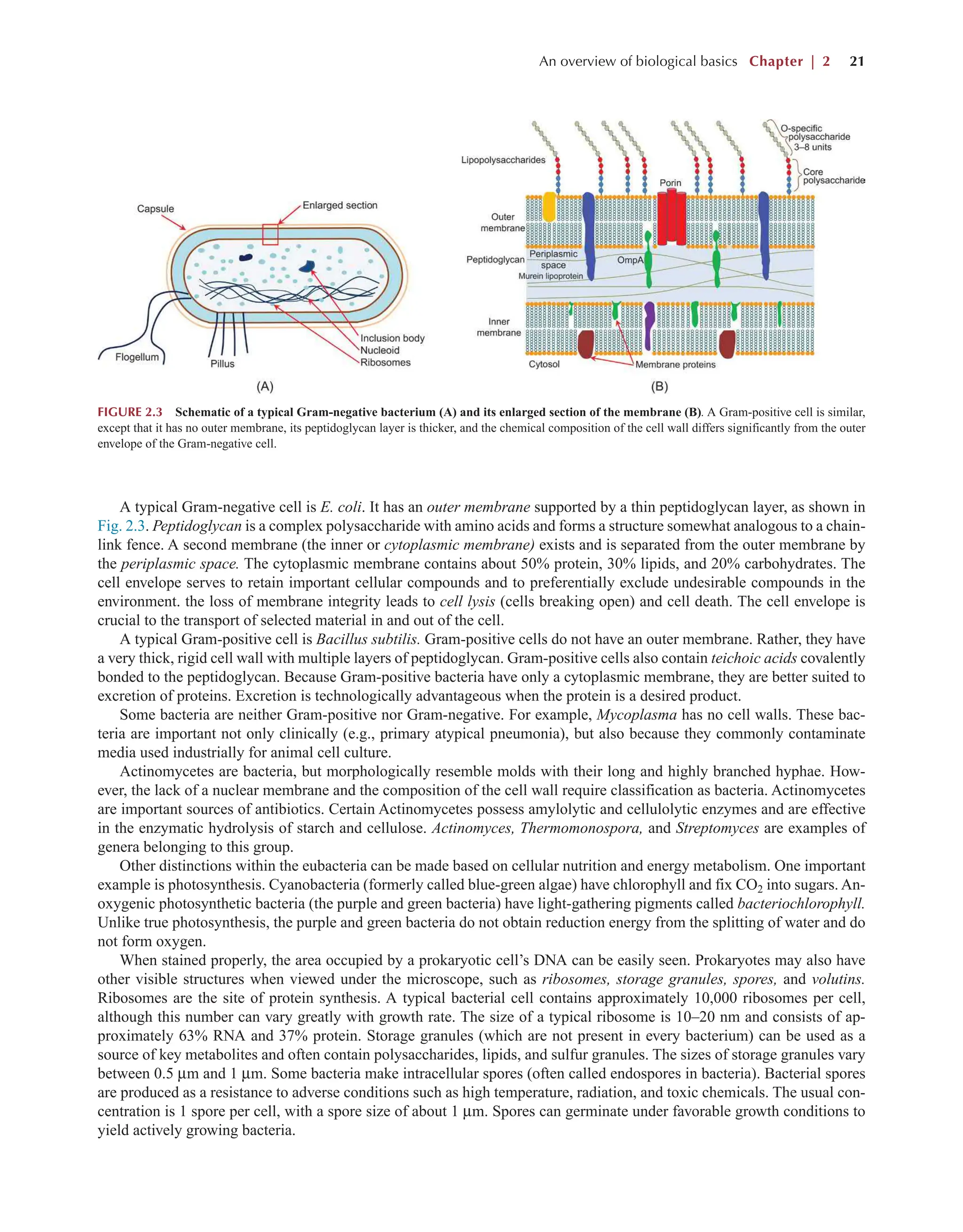

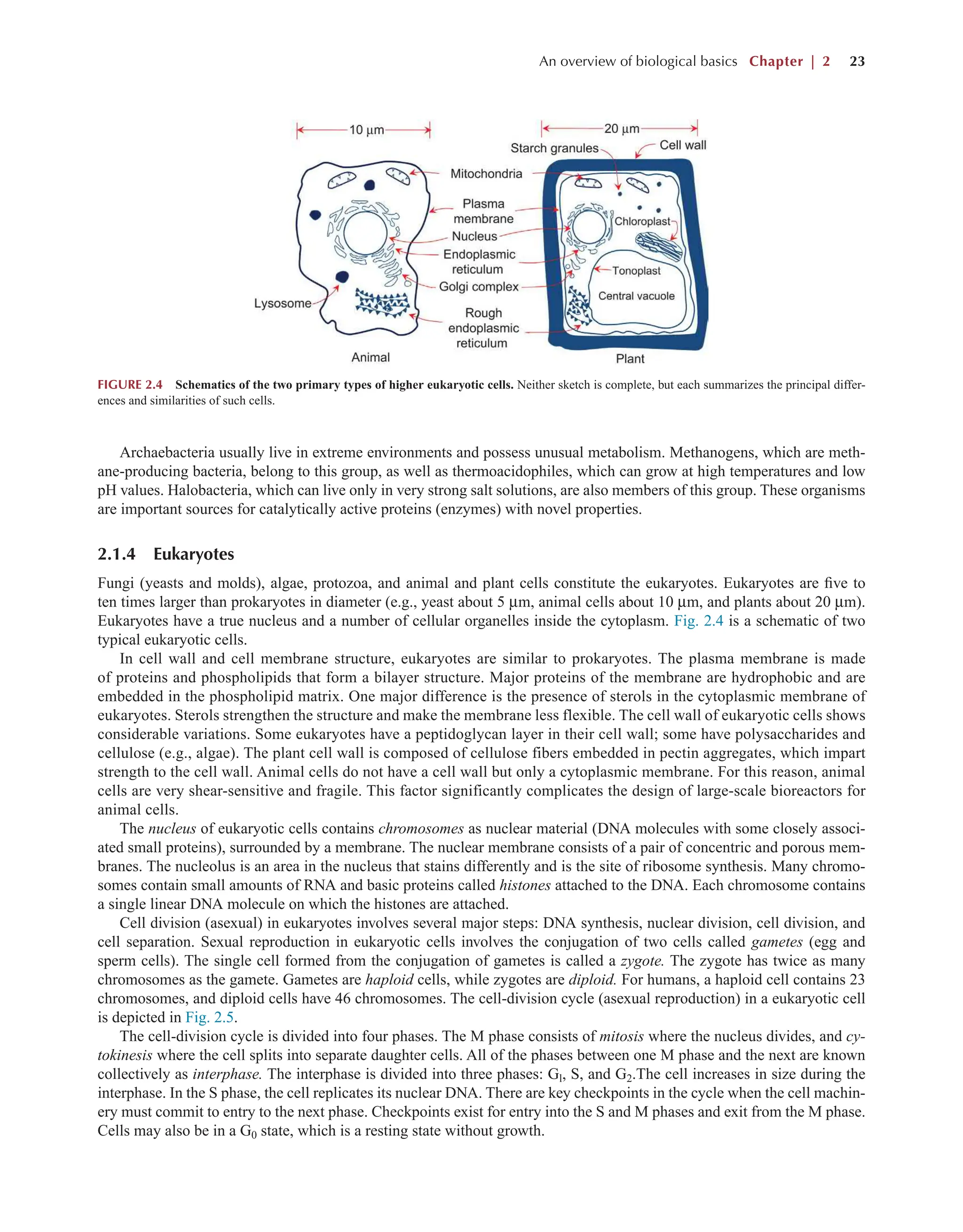

Bioprocess Engineering: Kinetics, Sustainability, and Reactor Design 3rd Edition Shijie Liu

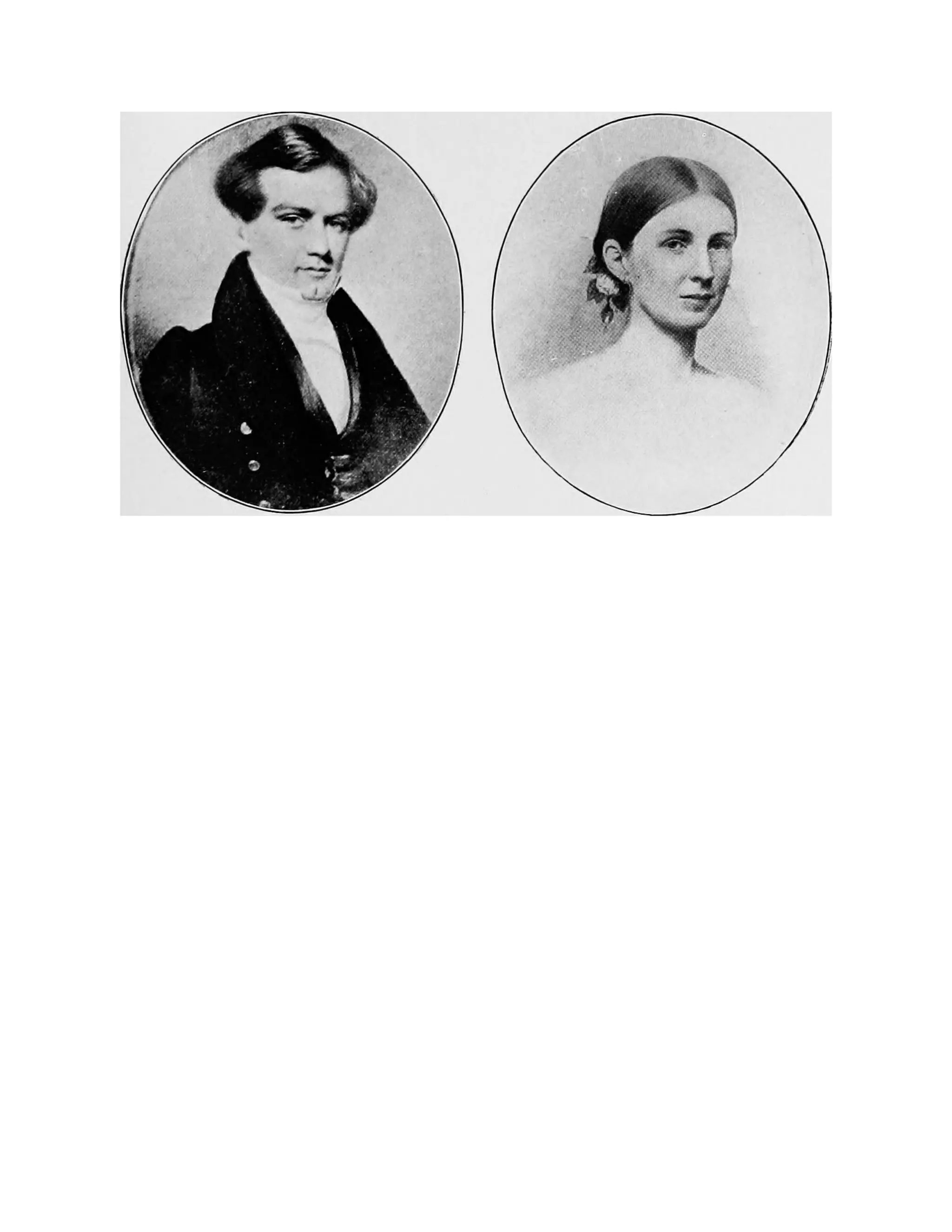

Bioprocess Engineering: Kinetics, Sustainability, and Reactor Design 3rd Edition Shijie Liu

![The text on this page is estimated to be only 5.65%

accurate

■1 1 ^^m'^-^] ^^^^^^^^^H ^^M ^^^^ I ■1 Py ' 1

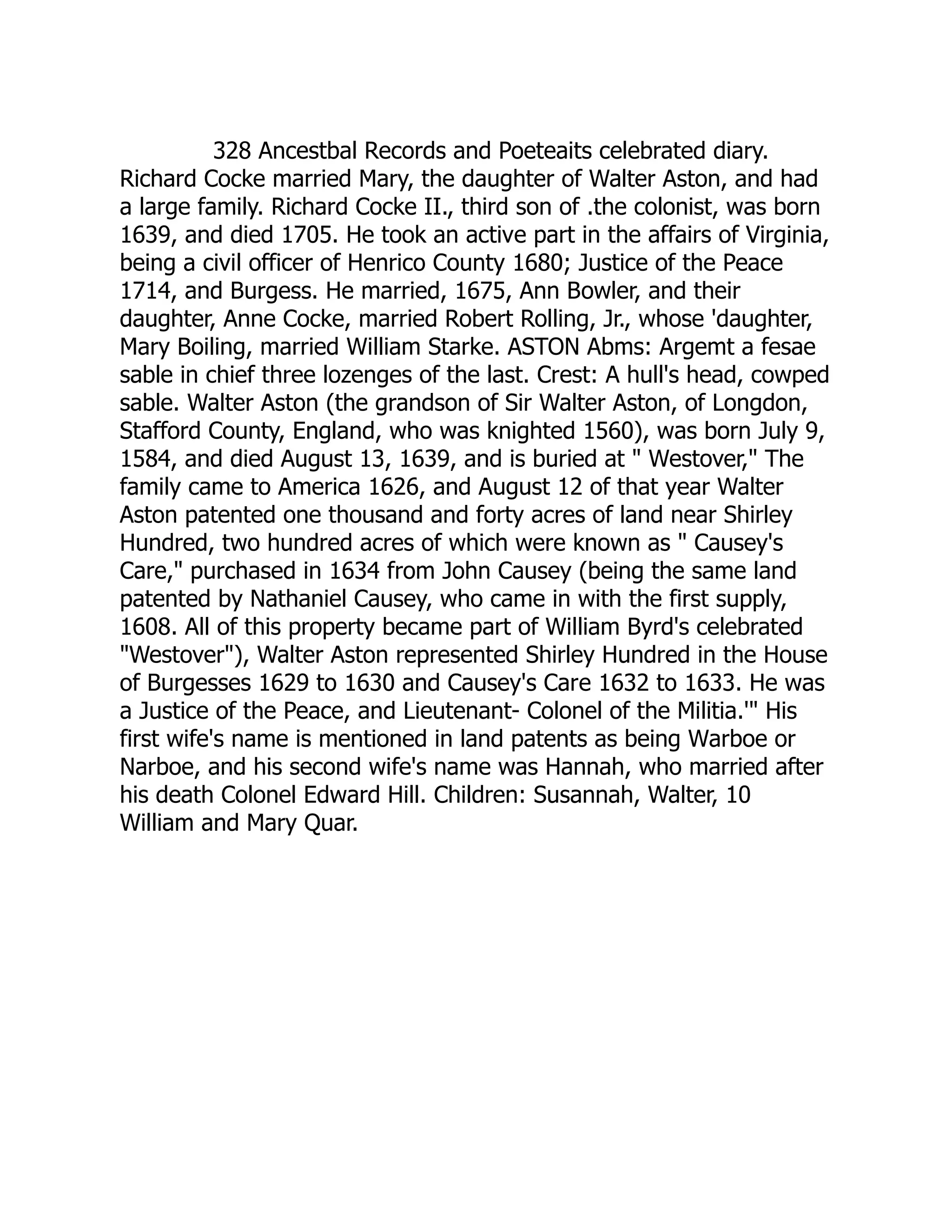

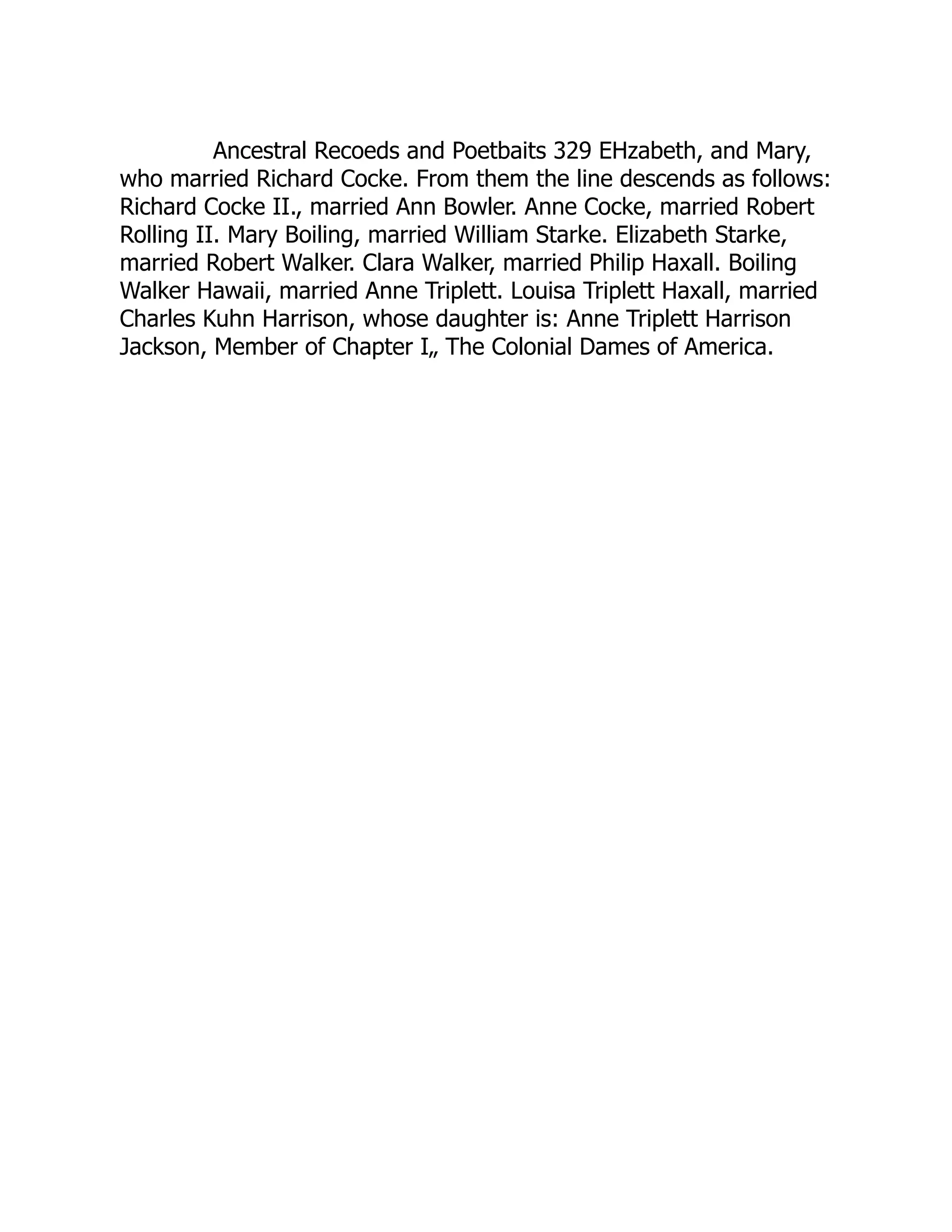

9^ iJ Elizabeth Maxwell Wife of Maj. John Swan Maj. Joiix Swan

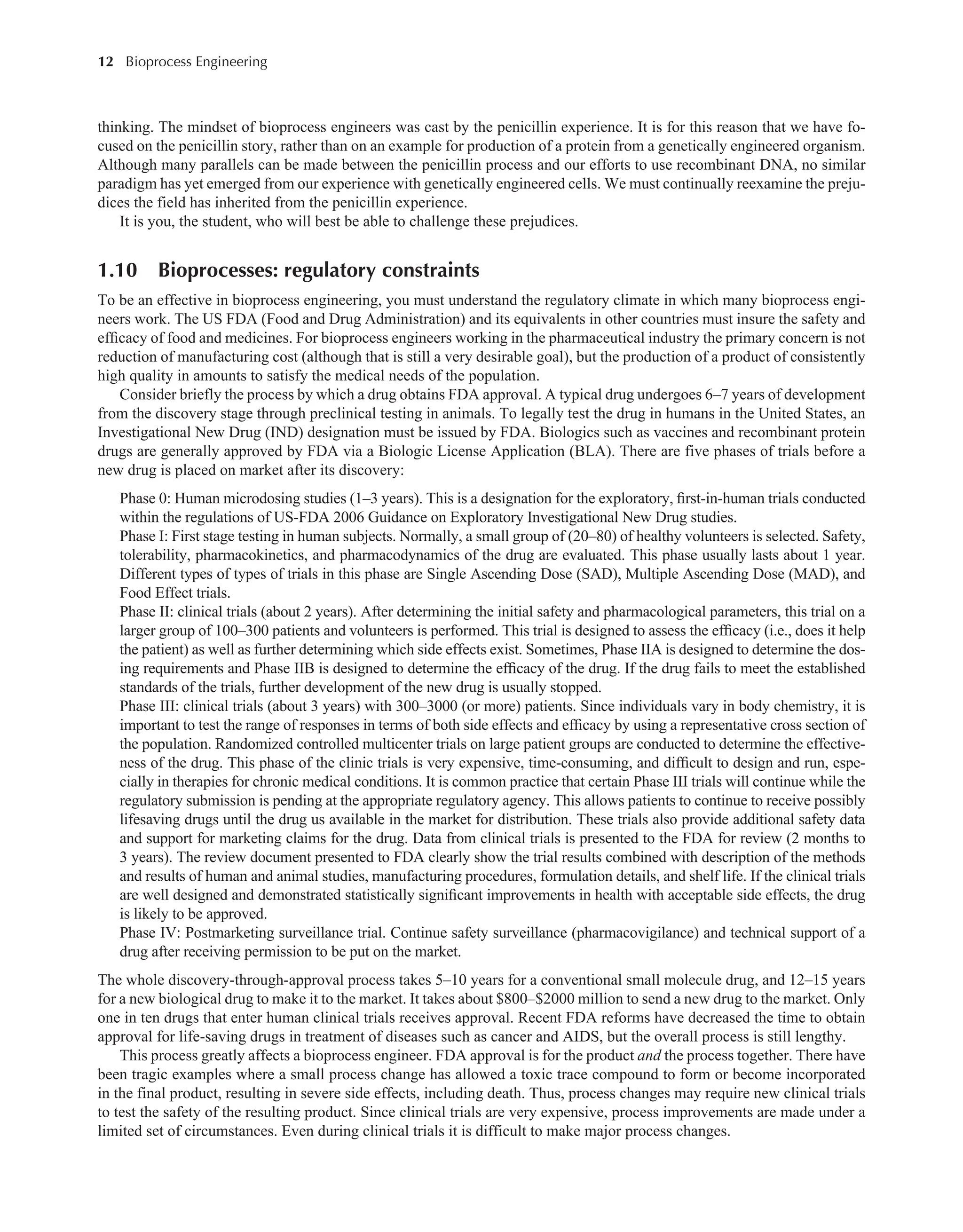

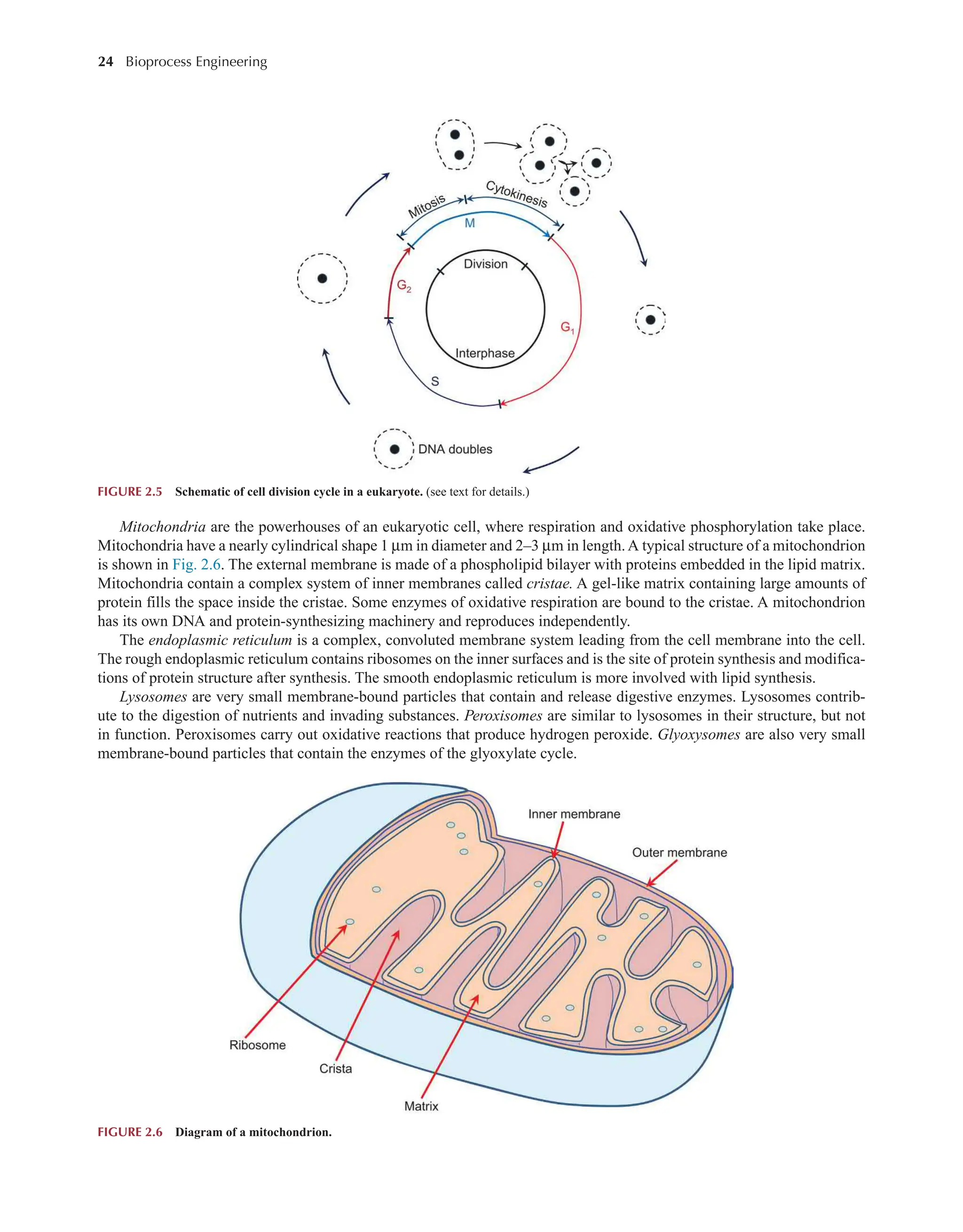

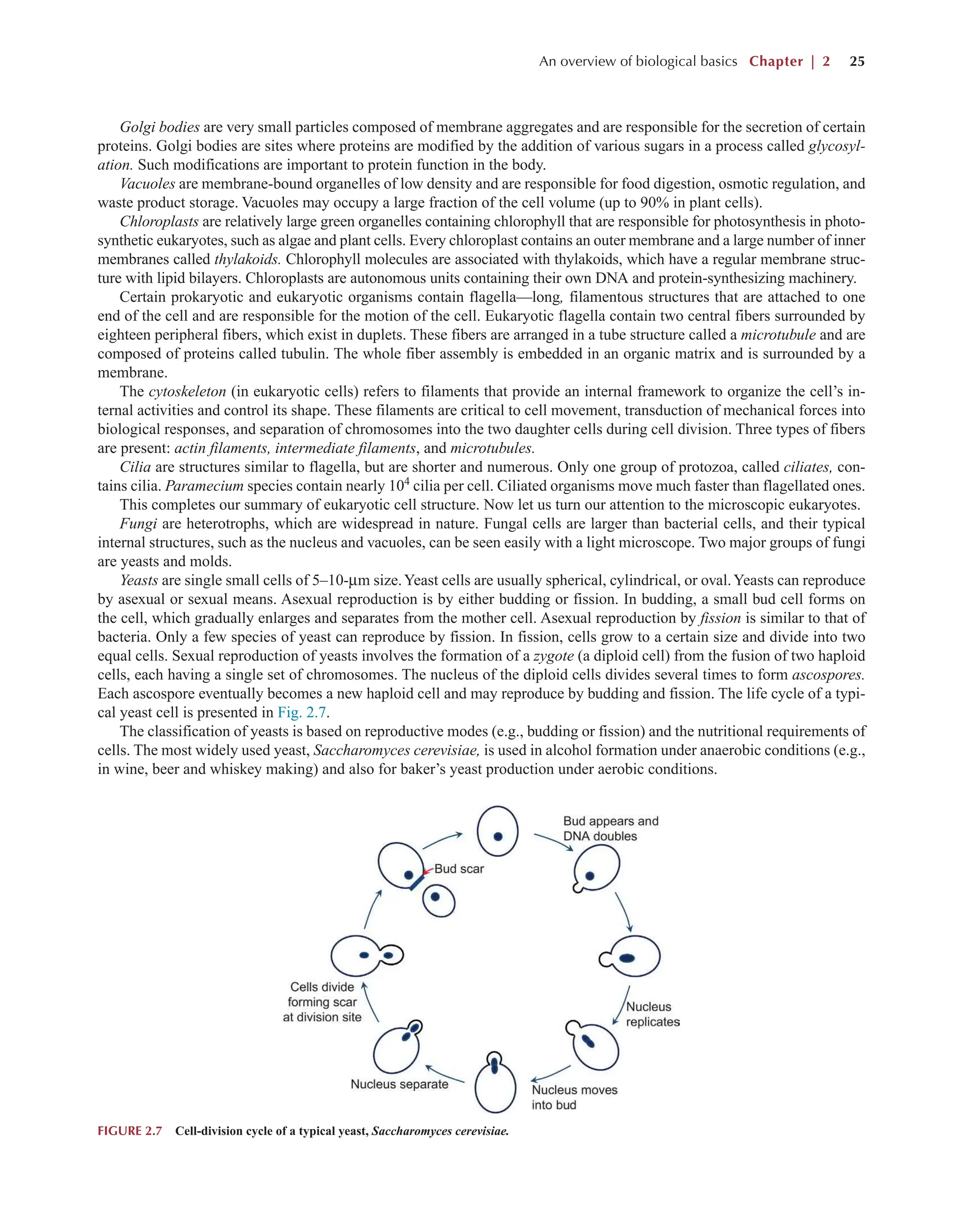

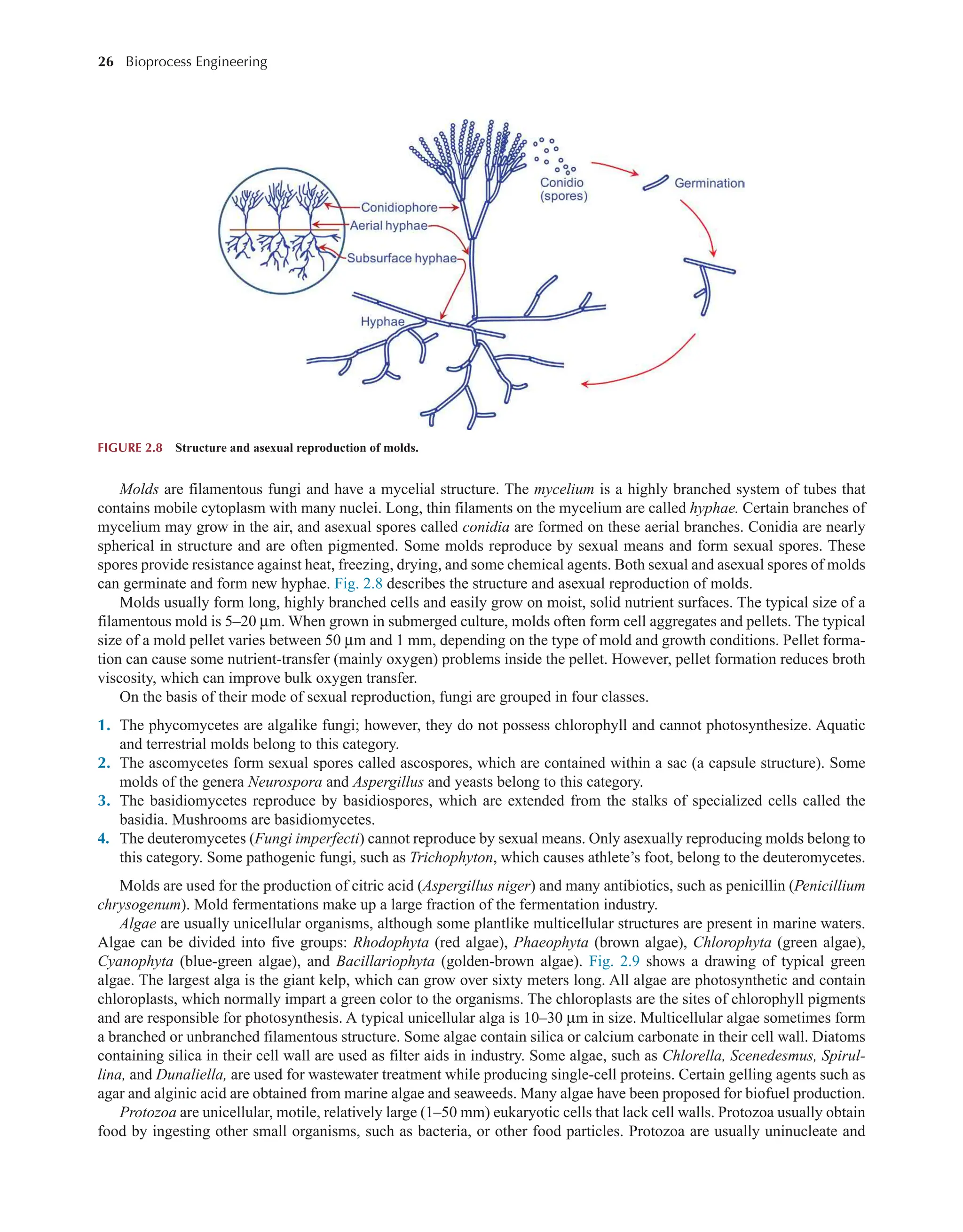

James Swan Elizametli Doxnell AVife of James Swan](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/63777-250727104444-a14e7cb7/75/Bioprocess-Engineering-Kinetics-Sustainability-and-Reactor-Design-3rd-Edition-Shijie-Liu-58-2048.jpg)