This document provides an overview of trends in endodontic treatment toward a more minimalistic, tissue-preserving approach known as "bio-minimalism." Recent developments discussed include:

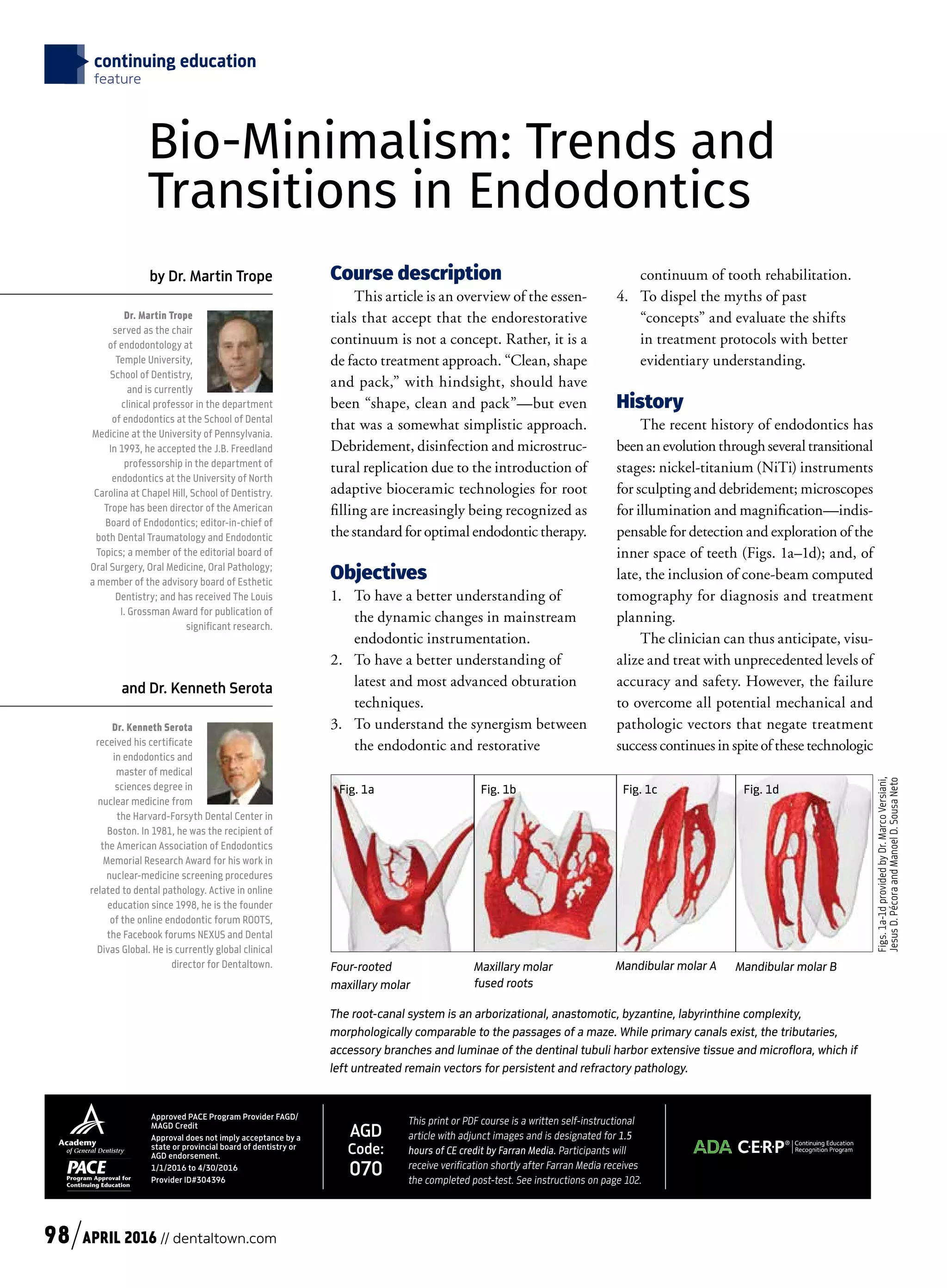

1) Advances in instrumentation and imaging technologies like nickel-titanium files, microscopes, and cone-beam CT that improve access and debridement while minimizing tissue removal.

2) Shifting access cavity designs toward greater dentin preservation and a more constrained outline to minimize cuspal flexure.

3) New obturation materials like bioceramics that provide antimicrobial properties and sealing without requiring large tapers or excess removal of inner root structure.

4) Moving beyond traditional concepts to evaluate shifts in protocols based