This document provides instructions for Assignment 3 of a sociology course. Students are asked to identify a research topic, formulate 1-2 research questions, and determine 1 dependent variable and 3 independent variables for a potential research paper. They are also instructed to consider what information friends or family could provide in a future survey for Assignment 4. The research should not involve vulnerable populations like minors. Initial ideas are acceptable even if still in progress.

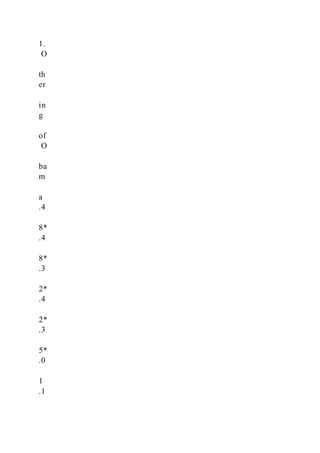

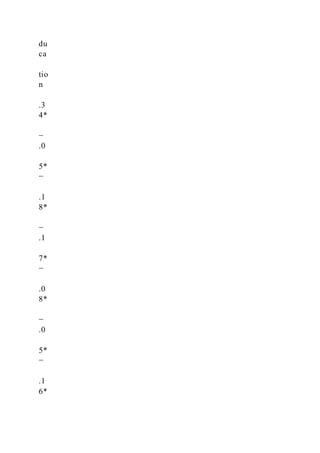

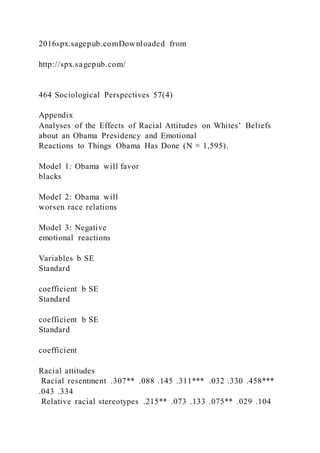

![the race literature has been that

because the normative racial discourse changed from the Jim

Crow to the post–civil rights era,

racial language has become more subtle and opaque (Bobo,

Kluegel, and Smith 1997; Bonilla-

Silva 2010). Accordingly, race analysts have come to focus

largely on symbolic forms of racism,

such as racial resentment (Sears and Henry 2005). Yet some

suggest that old fashioned overt

racism persists and thus should not be discounted (Huddy and

Feldman 2009).

1Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, USA

2University at Albany, State University of New York, Albany,

NY, USA

3University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

4Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA

Corresponding Author:

Daniel Tope, Department of Sociology, Florida State

University, 429 Bellamy Building, Tallahassee, FL 32306-2270,

USA.

Email: [email protected]

536140 SPXXXX10.1177/0731121414536140Sociological

PerspectivesTope et al.

research-article2014

at FLORIDA STATE UNIV LIBRARY on June 3,

2016spx.sagepub.comDownloaded from

mailto:[email protected]

http://spx.sagepub.com/

Tope et al. 451](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/assignment3researchquestionsvariablesyouwillidentify-220929052103-db53d1f9/85/Assignment-3-Research-Questions-VariablesYou-will-identify-3-320.jpg)

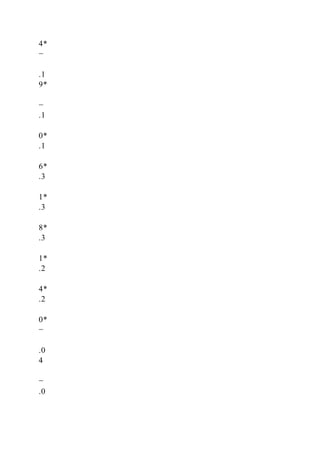

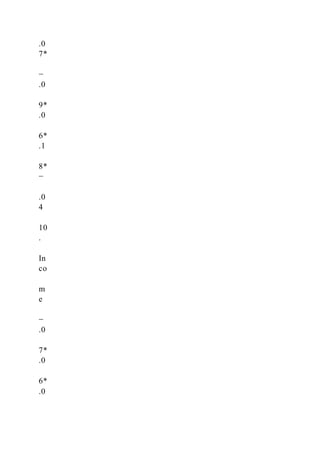

![Review of Political Science 7:383–408.

Jackman, Simon and Lynn Vavreck. 2009. The 2008

Cooperative Campaign Analysis Project, Release 2.1.

Palo Alto, CA: YouGov/Polimetrix [producer and distributor].

Kalkan, Kerem Ozan, Geofrey Layman, and Eric Uslaner. 2009.

“Bands of Others? Attitudes toward

Muslims in Contemporary American Society.” Journal of

Politics 71(3):1–16.

Kam, Cindy and Donald Kinder. 2012. “Ethnocentrism as a

Short-Term Force in the 2008 American

Presidential Election.” American Journal of Political Science

56:326–40.

Kinder, Donald R. and Cindy D. Kam. 2010. Us against Them:

Ethnocentric Foundations of American

Opinion. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

at FLORIDA STATE UNIV LIBRARY on June 3,

2016spx.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://www.harrisinteractive.com/NewsRoom/HarrisPolls/tabid/

447/ctl/ReadCustom%20Default/mid/1508/ArticleId/223/Default

.aspx

http://www.harrisinteractive.com/NewsRoom/HarrisPolls/tabi d/

447/ctl/ReadCustom%20Default/mid/1508/ArticleId/223/Default

.aspx

http://spx.sagepub.com/

Tope et al. 467

Kinder, Donald R. and Tali Mendelberg. 1995. “Cracks in](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/assignment3researchquestionsvariablesyouwillidentify-220929052103-db53d1f9/85/Assignment-3-Research-Questions-VariablesYou-will-identify-79-320.jpg)

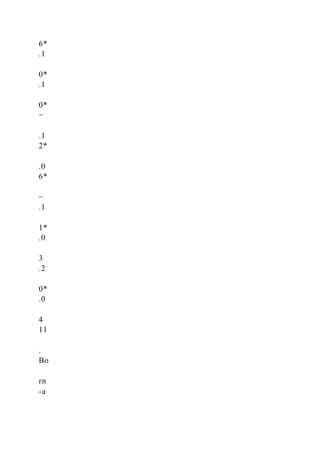

![2

OLIVER STRUNK: 'THE ELEMENTS OF STYLE' (4th edition)

First published in 1935, Copyright © Oliver Strunk

Last Revision: © William Strunk Jr. and Edward A. Tenney,

2000

Earlier editions: © Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc., 1959, 1972

Copyright © 2000, 1979, ALLYN & BACON, 'A Pearson

Education Company'

Introduction - © E. B. White, 1979 & 'The New Yorker

Magazine', 1957

Foreword by Roger Angell, Afterward by Charles Osgood,

Glossary prepared by Robert DiYanni

ISBN 0-205-30902-X (paperback), ISBN 0-205-31342-6

(casebound).

________

Machine-readable version and checking: O. Dag

E-mail: [email protected]

URL: http://orwell.ru/library/others/style/

Last modified on April, 2003.

3

The Elements of Style](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/assignment3researchquestionsvariablesyouwillidentify-220929052103-db53d1f9/85/Assignment-3-Research-Questions-VariablesYou-will-identify-88-320.jpg)

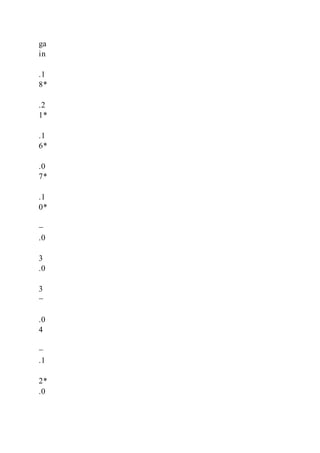

![Give this work to whoever looks idle.

In the last example, whoever is the subject of looks idle; the

object of the preposition to is

the entire clause whoever looks idle. When who introduces a

subordinate clause, its case

depends on its function in that clause.

Virgil Soames is the candidate whom we

think will win.

Virgil Soames is the candidate who we

think will win. [We think he will win.]

Virgil Soames is the candidate who we hope

to elect.

Virgil Soames is the candidate whom we

hope to elect. [We hope to elect him.]

A pronoun in a comparison is nominative if it is the subject of a

stated or understood verb.

Sandy writes better than I. (Than I write.)

In general, avoid "understood" verbs by supplying them.

I think Horace admires Jessica more than I. I think Horace

admires Jessica more than I

do.

Polly loves cake more than me. Polly loves cake more than she

loves me.

The objective case is correct in the following examples.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/assignment3researchquestionsvariablesyouwillidentify-220929052103-db53d1f9/85/Assignment-3-Research-Questions-VariablesYou-will-identify-119-320.jpg)

![animal, you may recall, was "blown by all the winds that pass

/And wet with all the

showers." And so must you as a young writer be. In our modern

idiom, we would say that

you must get wet all over. Mr. Stevenson, working in a plainer

style, said it with felicity, and

suddenly one cow, out of so many, received the gift of

immortality. Like the steadfast writer,

she is at home in the wind and the rain; and, thanks to one

moment of felicity, she will live

on and on and on.

1935

T H E E N D

________

Thank you John.

E-mail: [email protected]

79

mailto:[email protected]

Afterword

WILL STRUNK and E. B. White were unique collaborators.

Unlike Gilbert and Sullivan, or

Woodward and Bernstein, they worked separately and decades

apart.

We have no way of knowing whether Professor Strunk took

particular notice of Elwyn

Brooks White, a student of his at Cornell University in 1919.

Neither teacher nor pupil

could have realized that their names would be linked as they](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/assignment3researchquestionsvariablesyouwillidentify-220929052103-db53d1f9/85/Assignment-3-Research-Questions-VariablesYou-will-identify-224-320.jpg)