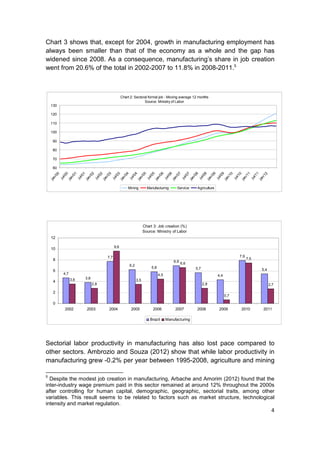

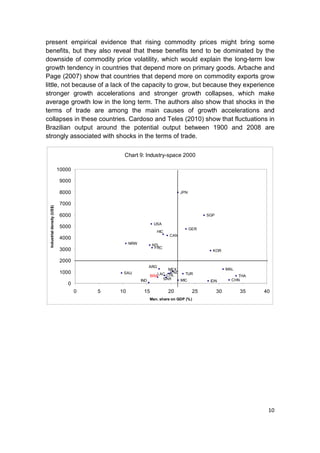

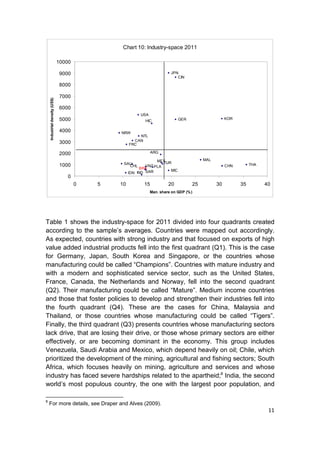

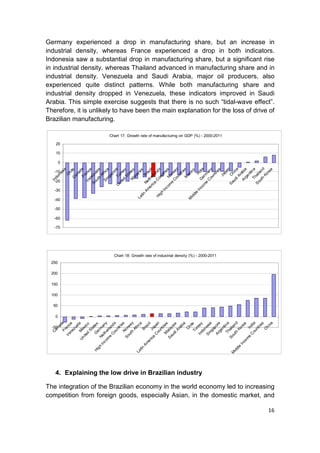

Brazil has built a dynamic manufacturing sector over decades that helped the country grow, but recent indicators show manufacturing growing slower than other sectors and its share of the economy declining. This analysis alone could be misleading, as manufacturing has undergone transformations like outsourcing production. By using a comparative industry analysis tool, the author finds evidence that Brazil's manufacturing sector is losing competitiveness at both the domestic and international levels, with declining output, employment, productivity, and trade surplus in manufacturing goods. The author argues that challenges facing Brazilian manufacturing require strategic policy reforms and investments to boost the sector.