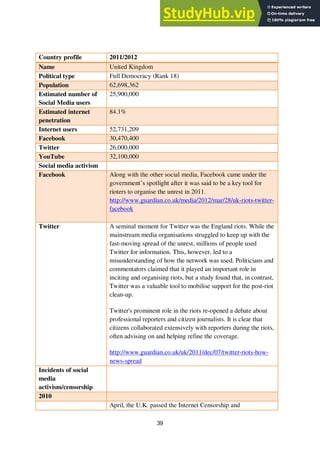

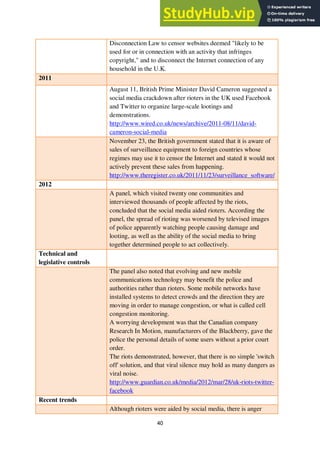

This document discusses how established democracies may be vulnerable to internet censorship despite their democratic principles of freedom of expression and access to information. It uses recent examples from the UK to examine governments' responses to social media activism during protests. The document analyzes key elements of democratic states, including consensus, participation, and access. It concludes that while established democracies have struggled to develop these democratic norms over time, social media is testing how firmly entrenched intellectual freedom is in these societies.