The document outlines key activities in Amazon's logistics sector, including order processing, inventory management, and transportation. It references various sources to discuss logistics management systems and integration's applications in evaluating integrals and understanding movement dynamics in calculus. Additionally, it explores the relationship between velocity, position, displacement, and the importance of integrals in determining these quantities.

![460 Chapter 6 Applications of Integration

The exact mass is obtained by taking the limit as n S ∞ and as

∆x S 0, which produces

a definite integral.

➤ Note that the units of the integral work

out as they should: r has units of mass

per length and dx has units of length, so

r1x2 dx has units of mass.

➤ Another interpretation of the mass

integral is that mass equals the average

value of the density multiplied by the

length of the bar b - a.

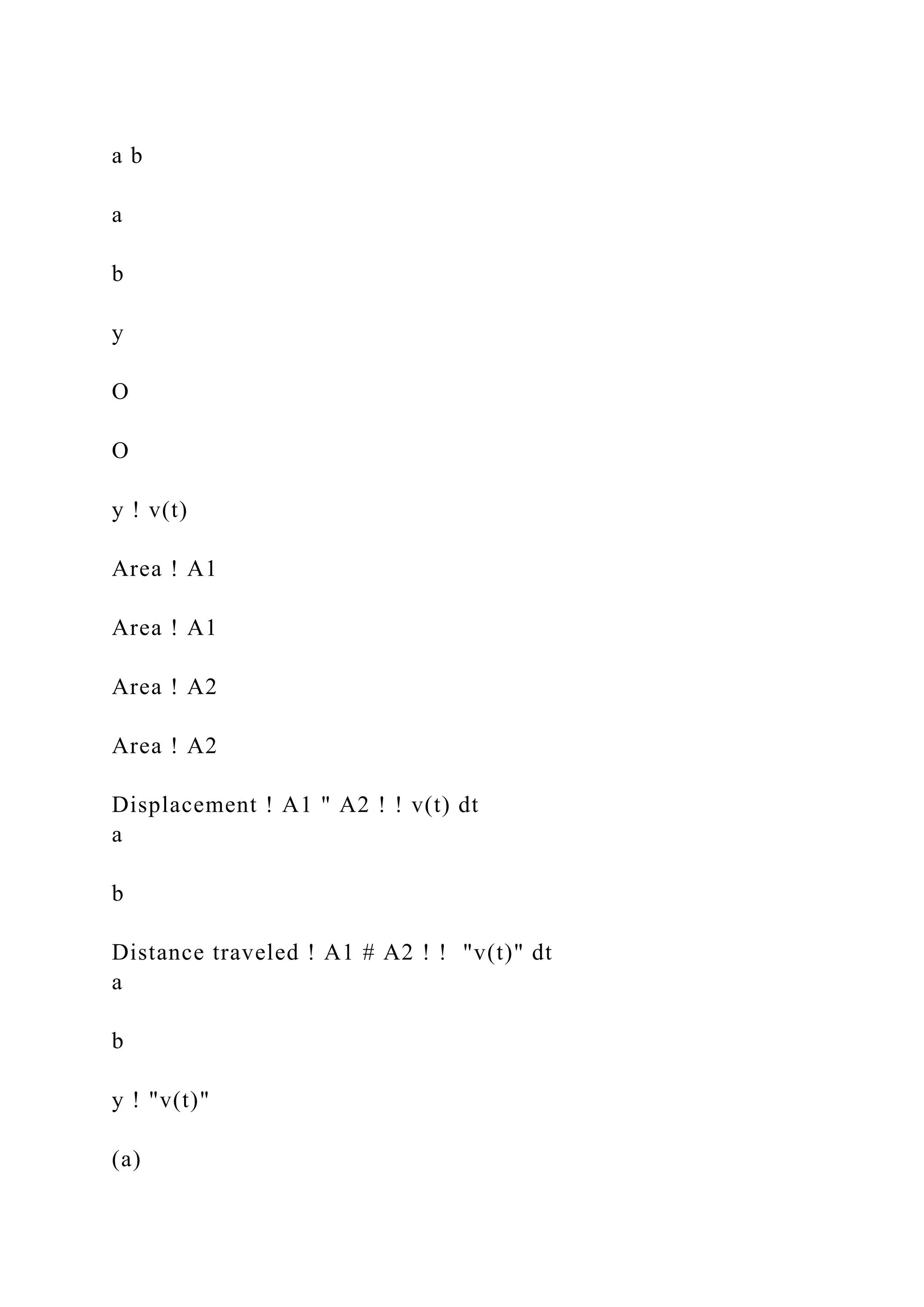

Figure 6.71

y

O xba

y ! F(x)

force

Force varies on [a, b]

DEFINITION Mass of a One-Dimensional Object

Suppose a thin bar or wire is represented by the interval a … x

… b with a density

function r (with units of mass per length). The mass of the

object is

m = L](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/amazon-221111011115-df89407d/75/Amazon-comThe-three-main-activities-that-e-docx-233-2048.jpg)

![force multiplied by the distance:

work = force # distance.

It is easiest to use metric units for force and work. A newton

1N2 is the force required to

give a 1-kg mass an acceleration of 1 m>s2. A joule 1J2 is 1

newton-meter [email protected], the

work done by a 1-N force over a distance of 1 m.

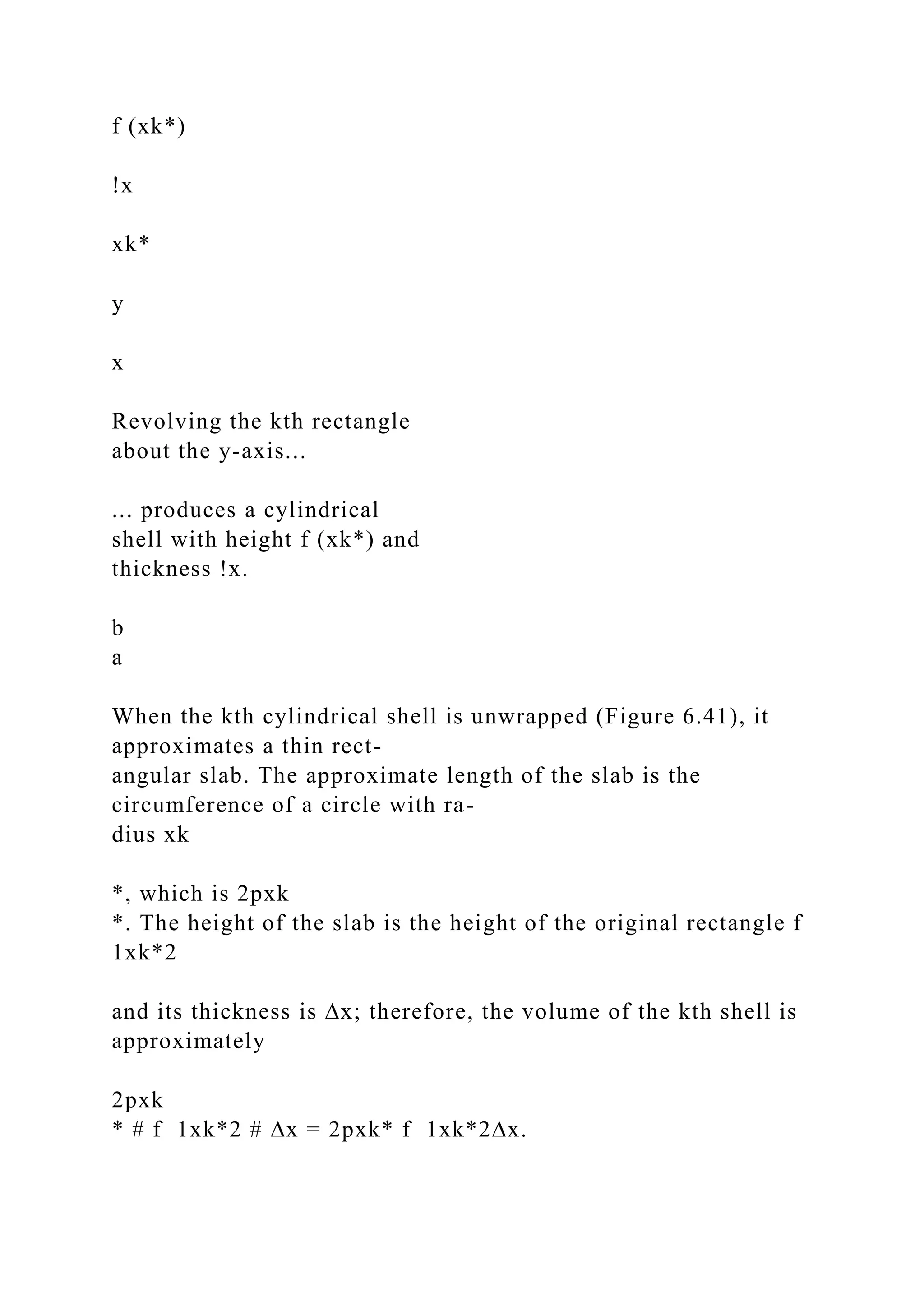

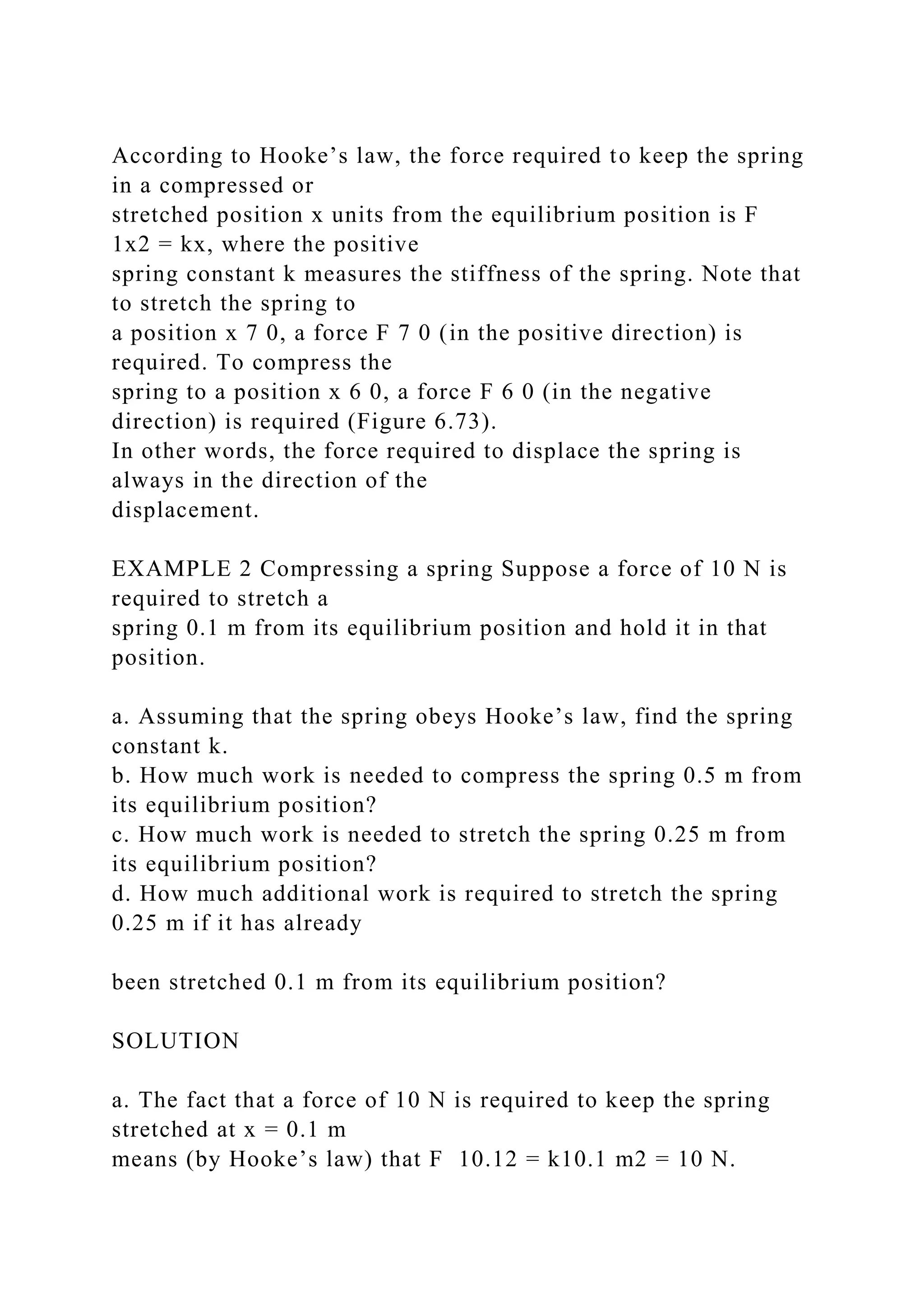

Calculus enters the picture with variable forces. Suppose an

object is moved along

the x-axis by a variable force F that is directed along the x-axis

(Figure 6.71). How much

work is done in moving the object between x = a and x = b?

Once again, we use the

slice-and-sum strategy.

The interval 3a, b4 is divided into n subintervals of equal length

∆x = 1b - a2>n.

We let xk

* be any point in the kth subinterval, for k = 1, c, n. On that

subinterval, the

force is approximately constant with a value of F 1xk*2.

Therefore, the work done in mov-

ing the object across the kth subinterval is approximately F

1xk*2∆x 1force # distance2.

Summing the work done over each of the n subintervals, the

total work over the interval 3a, b4 is approximately

W ≈ a

n

k = 1

F 1xk*2∆x.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/amazon-221111011115-df89407d/75/Amazon-comThe-three-main-activities-that-e-docx-235-2048.jpg)

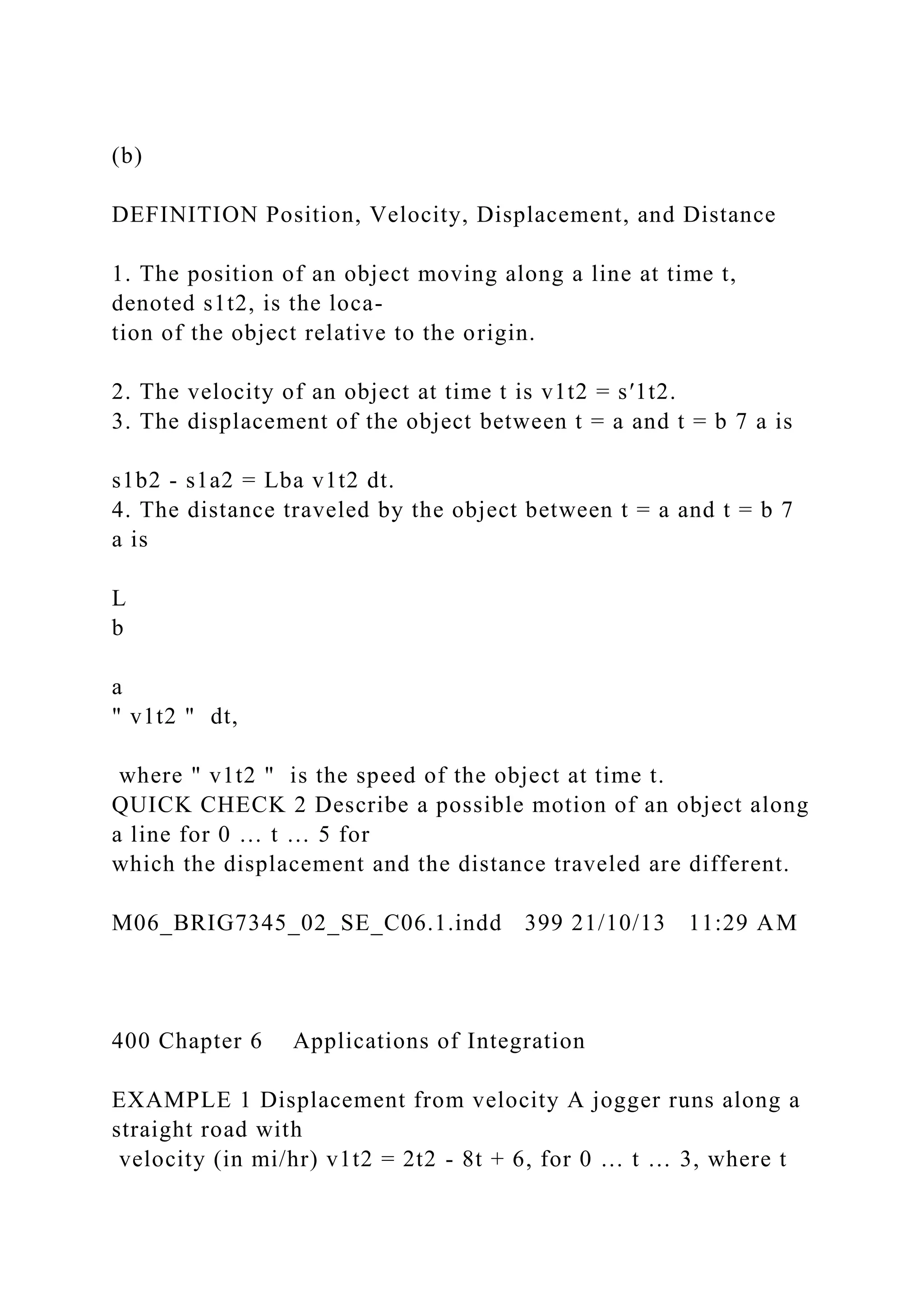

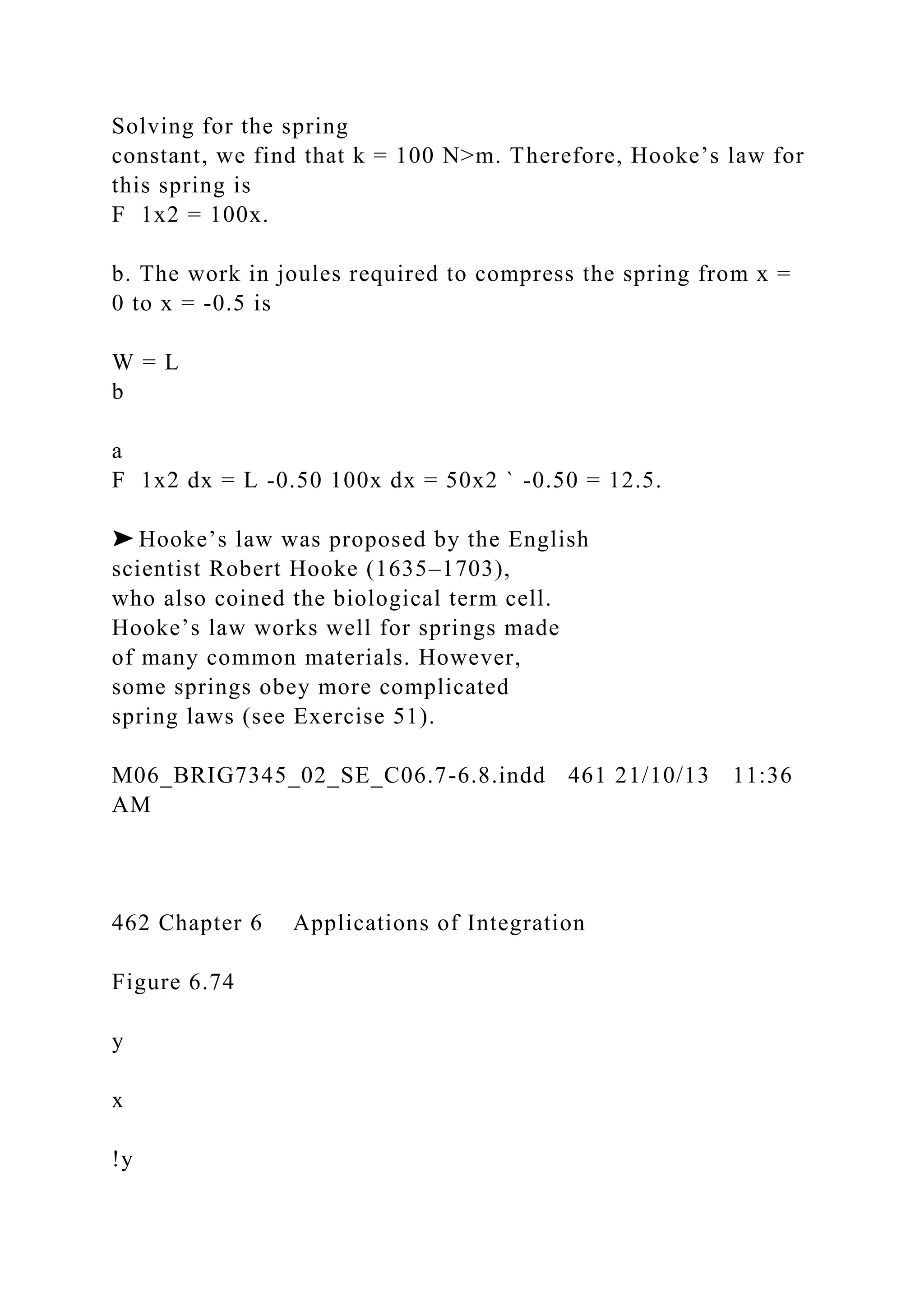

![is y = h, where h Ú b

(Figure 6.74). We now slice the water into n horizontal layers,

each having thickness ∆y.

➤ Notice again that the units in the integral

are consistent. If F has units of N and x

has units of m, then W has units of F dx,

or [email protected], which are the units of work 11

[email protected] = 1 J2.

QUICK CHECK 4 In Example 2, explain

why more work is needed in part

(d) than in part (c), even though the

displacement is the same.

M06_BRIG7345_02_SE_C06.7-6.8.indd 462 21/10/13 11:36

AM

6.7 Physical Applications 463

PROCEDURE Solving Lifting Problems

1. Draw a y-axis in the vertical direction (parallel to gravity)

and choose a con-

venient origin. Assume the interval 3a, b4 corresponds to the

vertical extent of

the fluid.

2. For a … y … b, find the cross-sectional area A1y2 of the

horizontal slices and

the distance D1y2 the slices must be lifted.

3. The work required to lift the water is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/amazon-221111011115-df89407d/75/Amazon-comThe-three-main-activities-that-e-docx-245-2048.jpg)

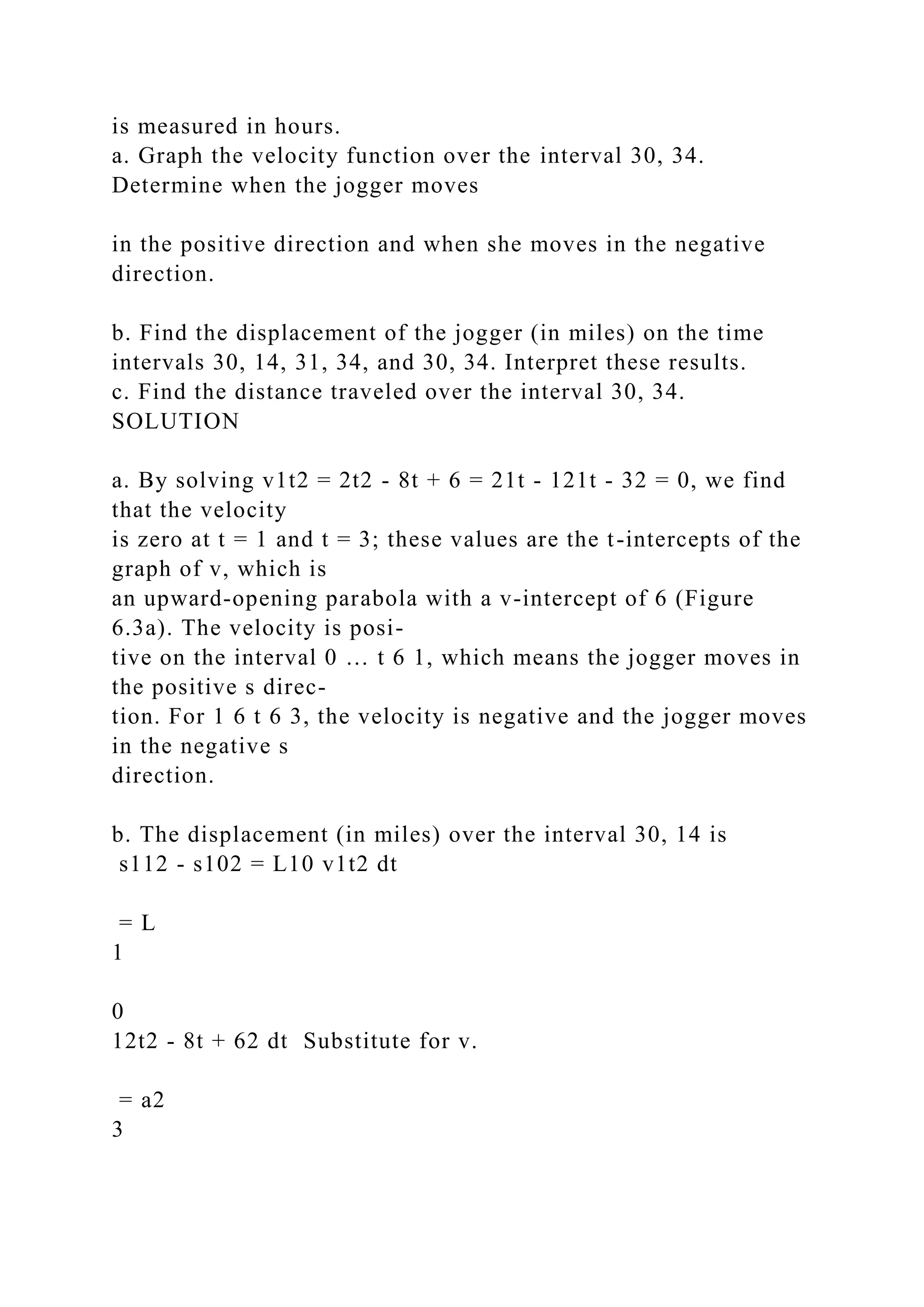

![-y

r)

y ! E(t)

QUICK CHECK 4 If a quantity decreases

by a factor of 8 every 30 years, what is

its half-life?

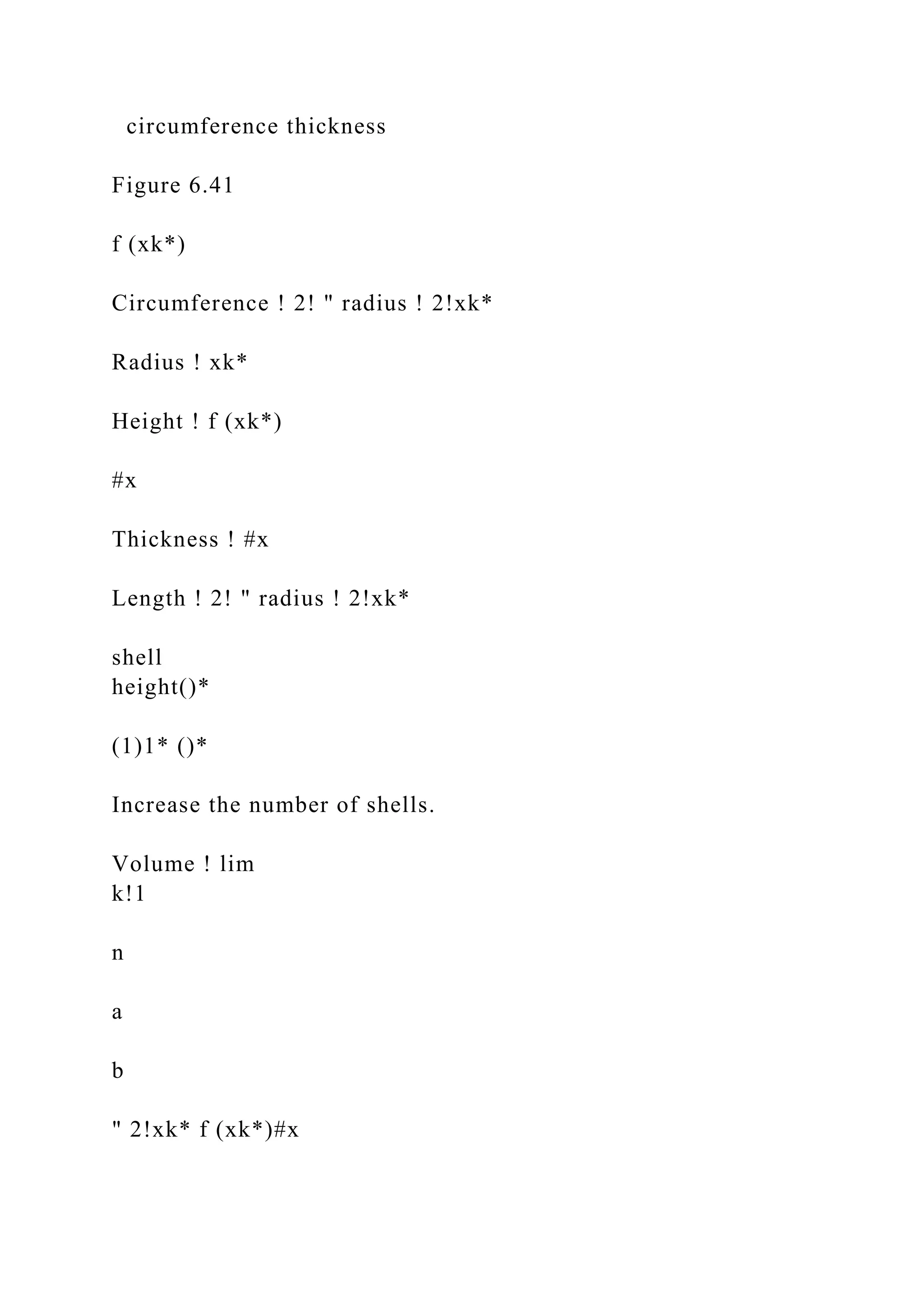

Exponential Decay Functions

Exponential decay is described by functions of the form y1t2 =

y0e-kt. The initial

value of y is y102 = y0, and the rate constant k 7 0 determines

the rate of decay.

Exponential decay is characterized by a constant relative decay

rate. The constant

half-life is T1>2 = ln 2k , with the same units as t.

M06_BRIG7345_02_SE_C06.9.indd 486 06/11/13 8:11 AM

6.9 Exponential Models 487

Radiometric Dating A powerful method for estimating the age

of ancient objects (for

example, fossils, bones, meteorites, and cave paintings) relies

on the radioactive decay of

certain elements. A common version of radiometric dating uses

the carbon isotope [email protected],

which is present in all living matter. When a living organism

dies, it ceases to replace [email protected],

and the [email protected] that is present decays with a half-life

of about T1>2 = 5730 years. Comparing

the [email protected] in a living organism to the amount in a](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/amazon-221111011115-df89407d/75/Amazon-comThe-three-main-activities-that-e-docx-320-2048.jpg)

![dead sample provides an estimate of its age.

EXAMPLE 5 Radiometric dating Researchers determine that a

fossilized bone has

30% of the [email protected] of a live bone. Estimate the age of

the bone. Assume a half-life for [email protected]

of 5730 years.

SOLUTION The exponential decay function y1t2 = y0e-kt

represents the amount of

C-14 in the bone t years after its owner died. By the half-life

formula, T1>2 = 1ln 22>k.

Substituting T1>2 = 5730 yr, the rate constant is

k =

ln 2

T1>2 = ln 25730 yr ≈ 0.000121 yr-1.

Assume that the amount of [email protected] in a living bone is

y0. Over t years, the amount of

[email protected] in the fossilized bone decays to 30% of its

initial value, or 0.3y0. Using the decay

function, we have

0.3y0 = y0e-0.000121t.

Solving for t, the age of the bone (in years) is

t =

ln 0.3

-0.000121 ≈ 9950.

Related Exercises 21–26

Pharmacokinetics Pharmacokinetics describes the processes by](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/amazon-221111011115-df89407d/75/Amazon-comThe-three-main-activities-that-e-docx-321-2048.jpg)

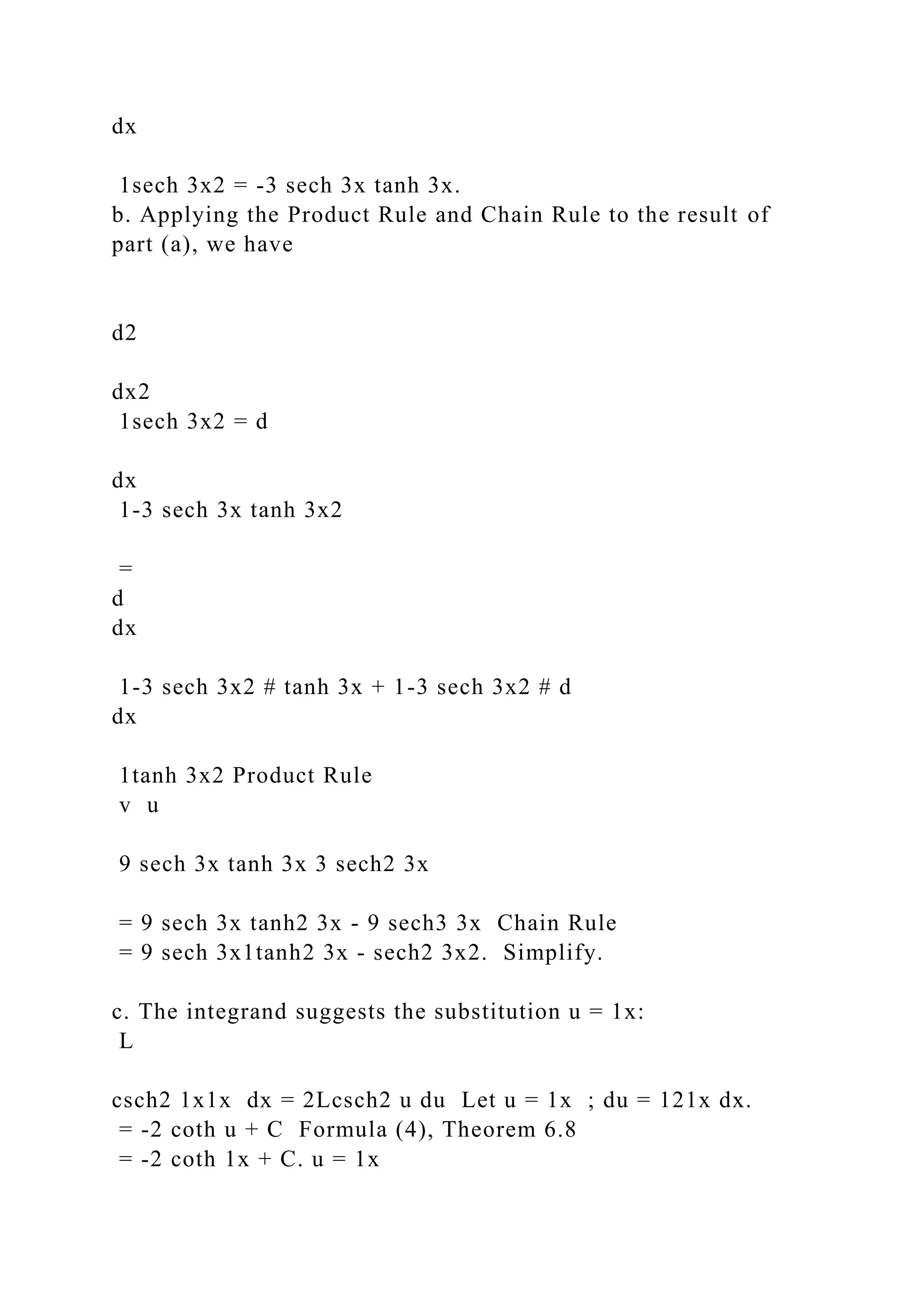

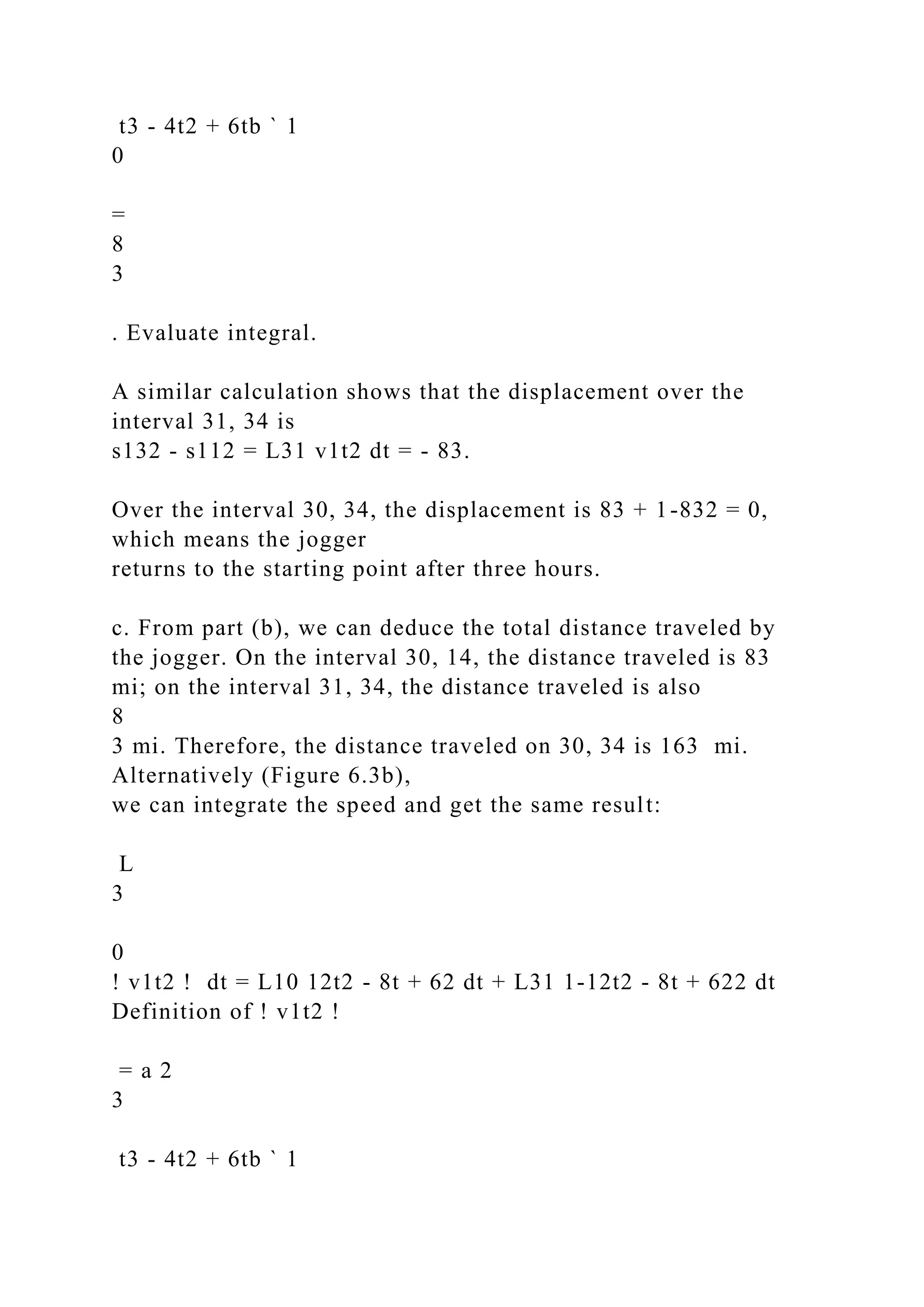

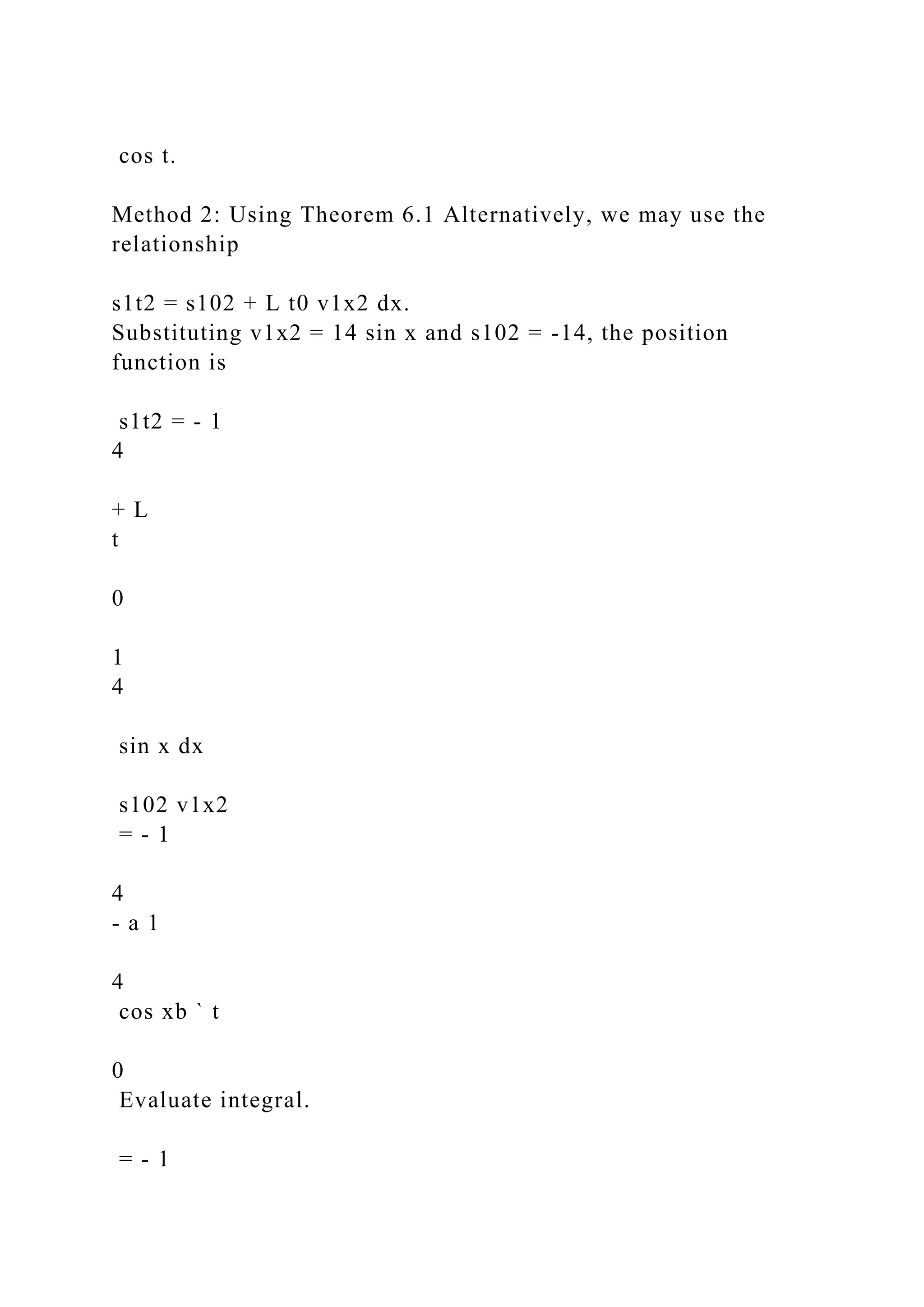

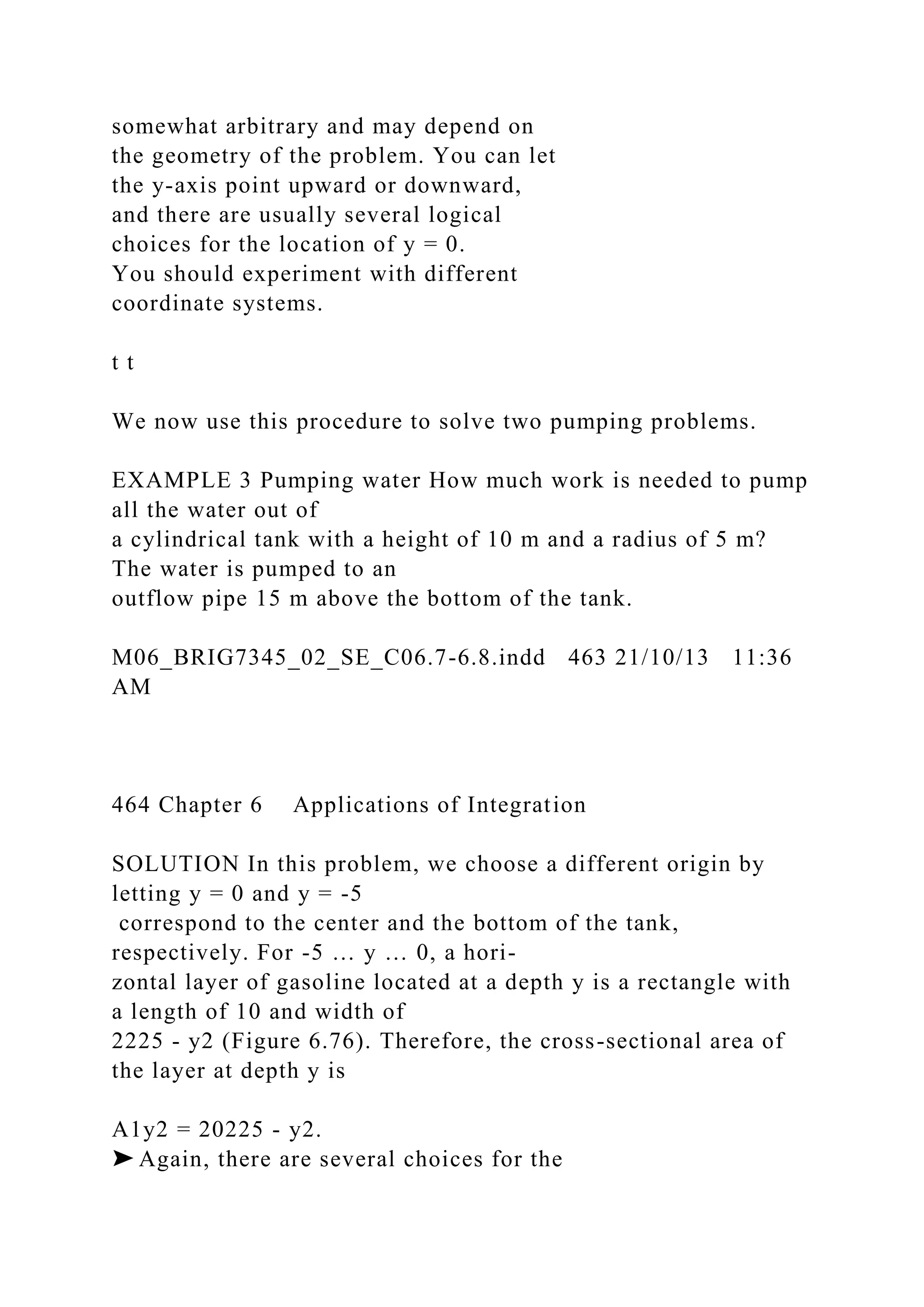

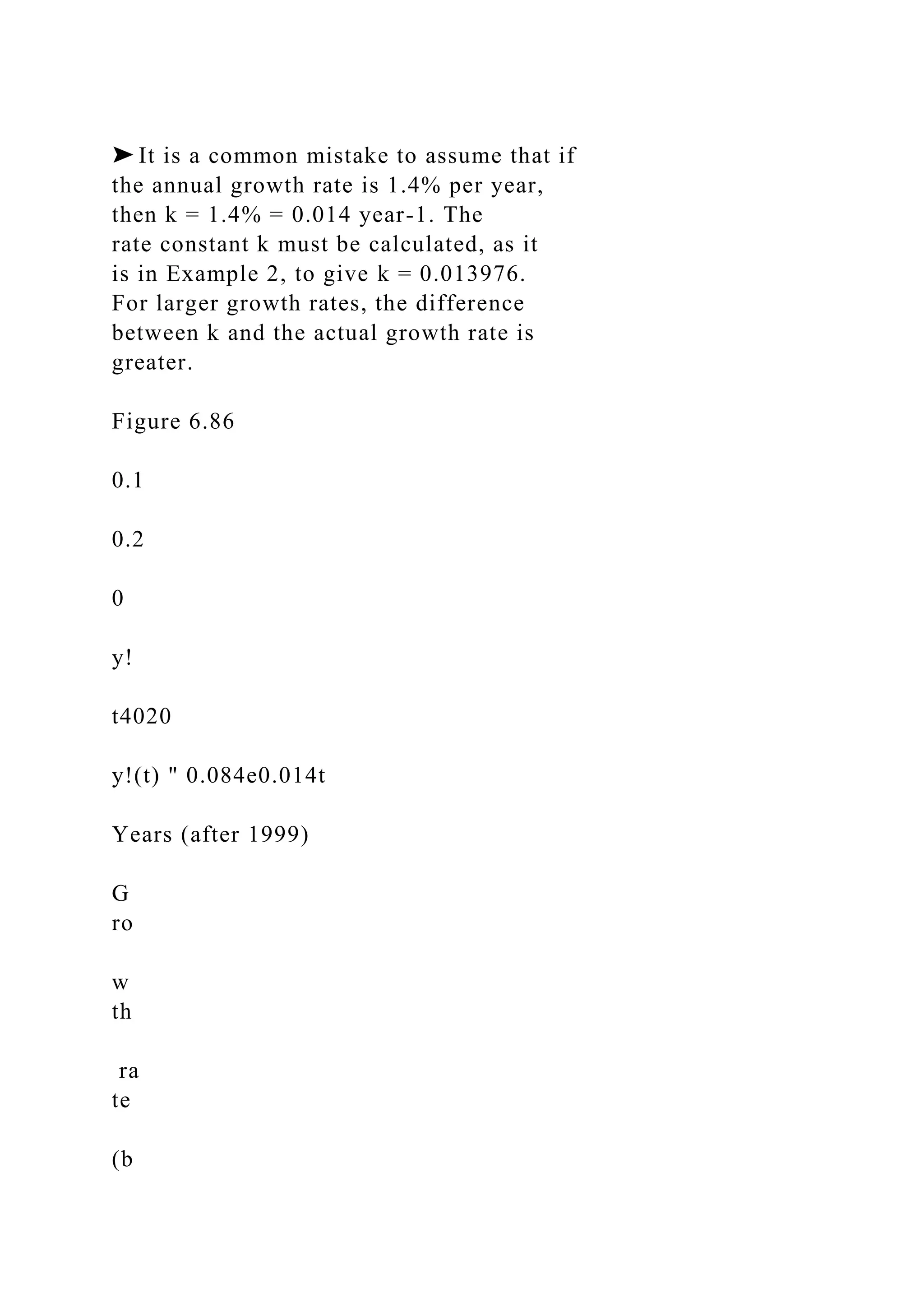

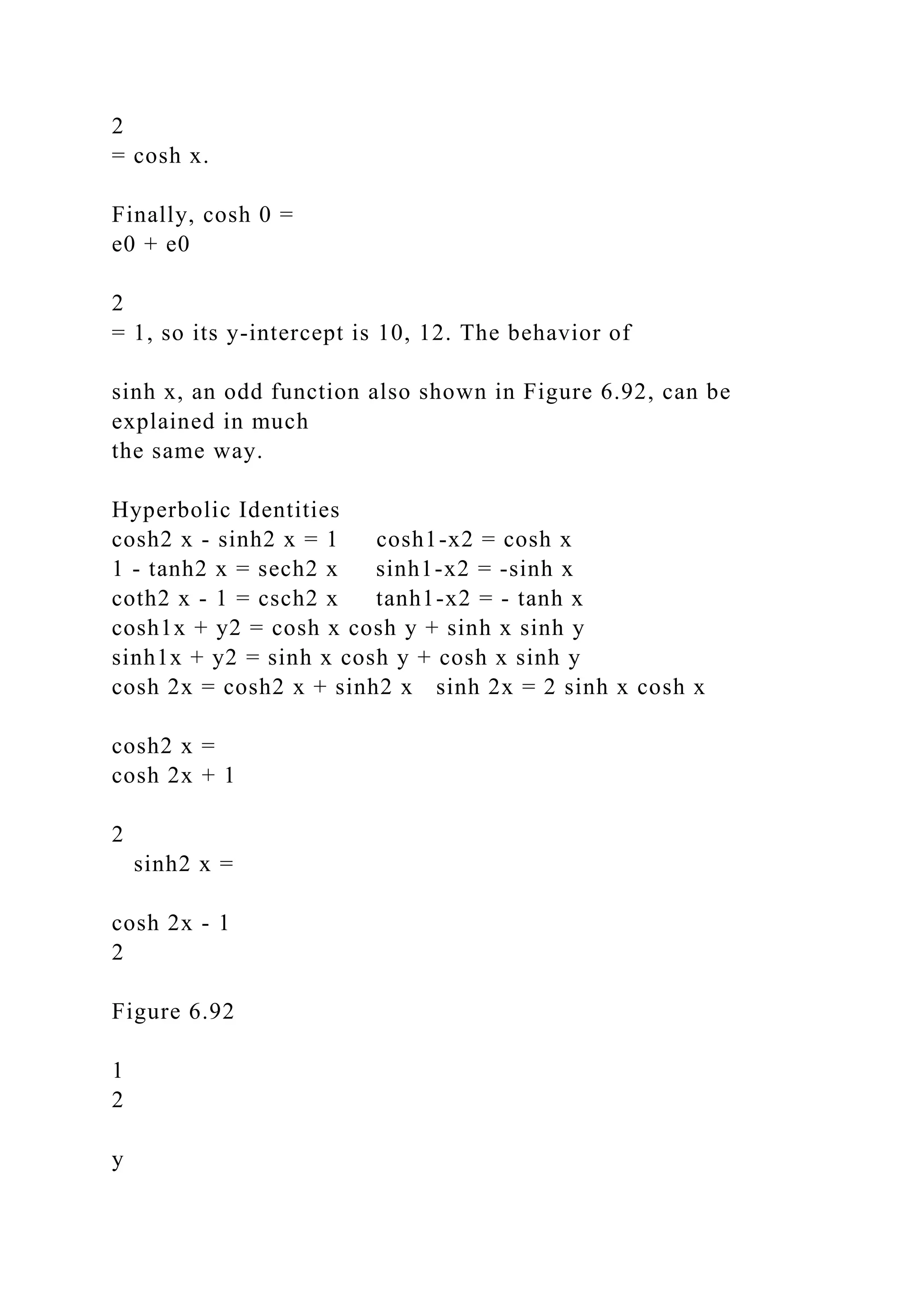

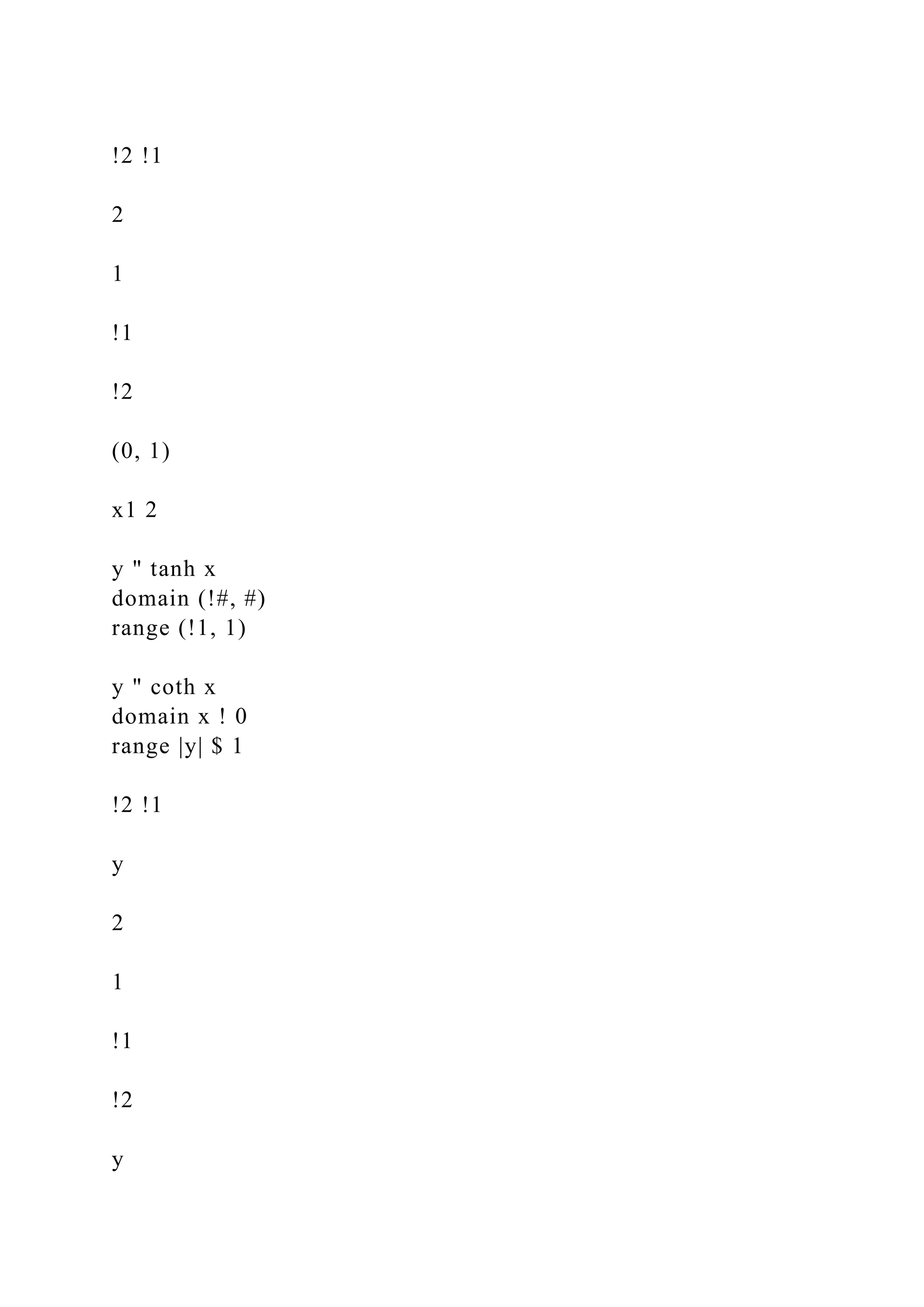

![x1 2

y " sech x

domain (!#, #)

range (0, 1]

y " csch x

domain x ! 0

range y ! 0

QUICK CHECK 1 Use the definition of the hyperbolic sine to

show that sinh x is an odd

function.

The graphs of the other four hyperbolic functions are shown in

Figure 6.93. As a con-

sequence of their definitions, we see that the domain of cosh x,

sinh x, tanh x, and sech x is 1- ∞ , ∞2, whereas the domain of

coth x and csch x is the set of all real numbers excluding 0.

QUICK CHECK 2 Explain why the graph of tanh x has the

horizontal asymptotes y = 1 and

y = -1.

M06_BRIG7345_02_SE_C06.10.indd 493 21/10/13 11:30 AM

494 Chapter 6 Applications of Integration

Derivatives and Integrals of Hyperbolic Functions

Because the hyperbolic functions are defined in terms of ex and

e-x, computing their

derivatives is straightforward. The derivatives of the hyperbolic

functions are given in](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/amazon-221111011115-df89407d/75/Amazon-comThe-three-main-activities-that-e-docx-336-2048.jpg)