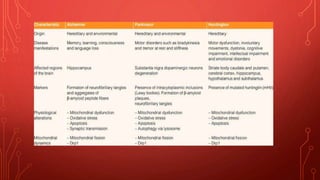

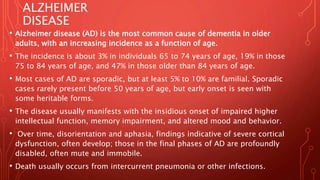

The document discusses neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and prion disease. It notes that neurodegenerative diseases are characterized by the progressive loss of neurons affecting functional groups. Alzheimer's disease is the most common cause of dementia and involves the accumulation of amyloid beta and tau proteins forming plaques and tangles respectively. The pathogenesis involves these proteins as well as inflammatory reactions. Morphological features include cortical atrophy, enlarged ventricles, neuritic plaques, and neurofibrillary tangles in neurons.

![• Over time, this self-amplifying process leads to the accumulation

of a high burden of pathogenic PrPsc molecules in the brain.

• Certain mutations in the gene encoding PrPc (PRNP) accelerate the

rate of spontaneous conformational change; these variants are

associated with early-onset familial forms of prion disease

(familial Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease [fCJD]).

• PrPc also may change its conformation spontaneously (but at an

extremely low rate), accounting for sporadic cases of prion

disease (sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease [sCJD]).

• Accumulation of PrPsc in neural tissue seems to be the cause of

cell injury, but the mechanisms underlying the cytopathic changes

and eventual neuronal death are still unknown.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alzheimerdisease-230216023451-a3101be0/85/Alzheimer-disease-pptx-22-320.jpg)