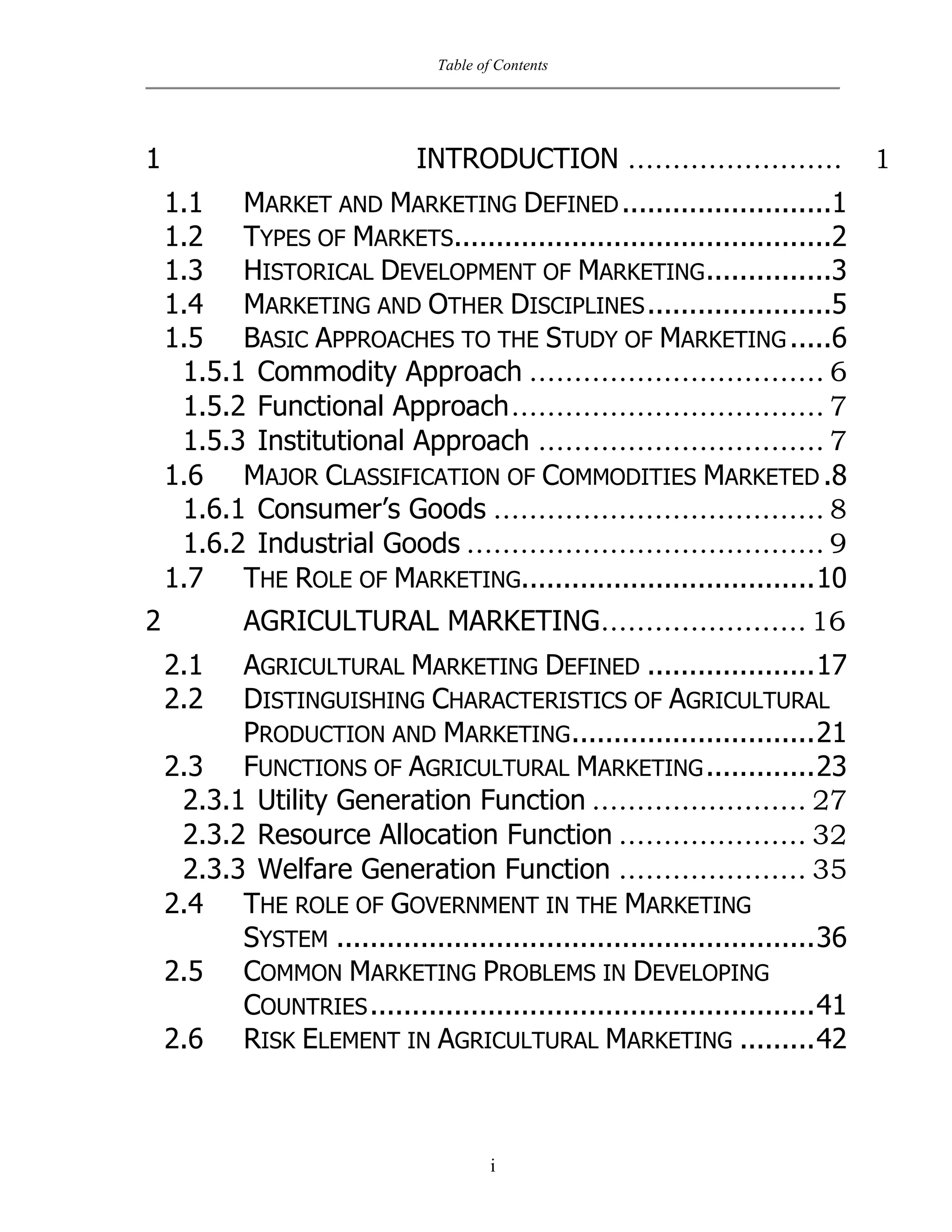

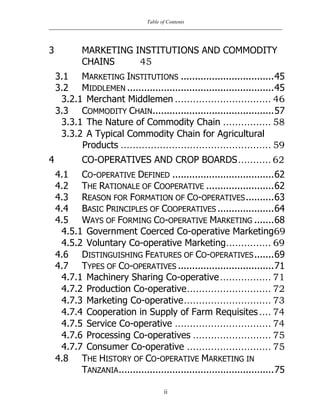

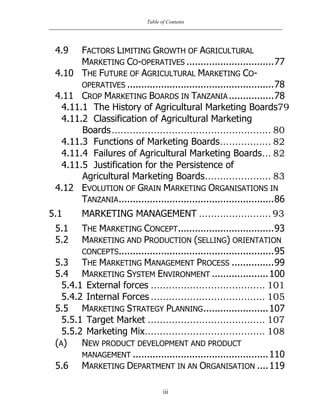

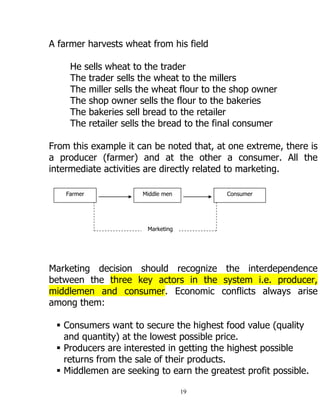

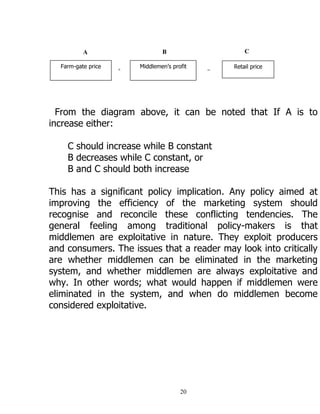

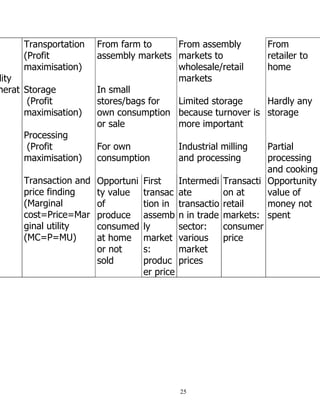

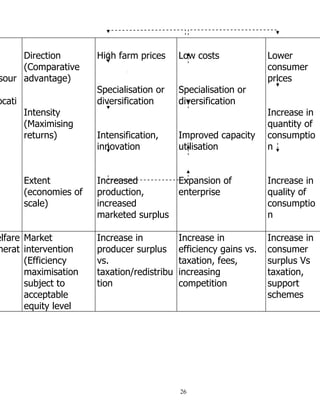

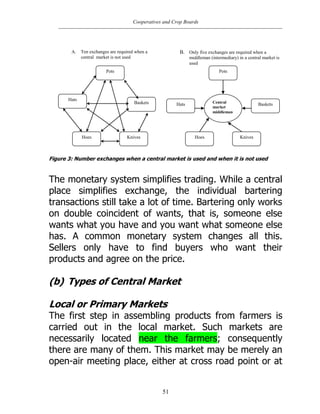

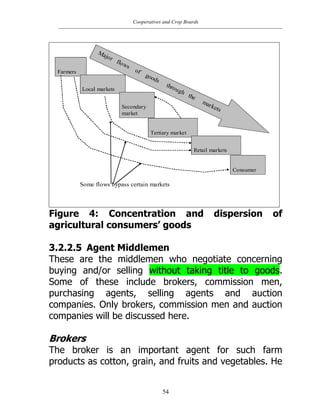

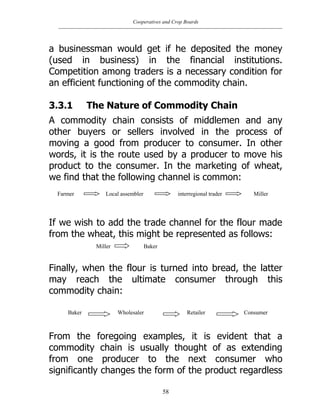

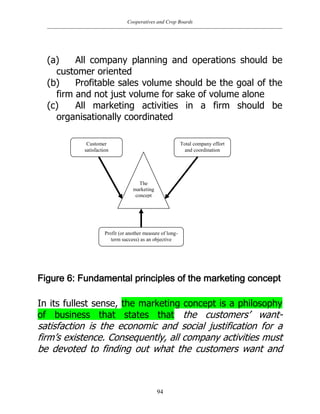

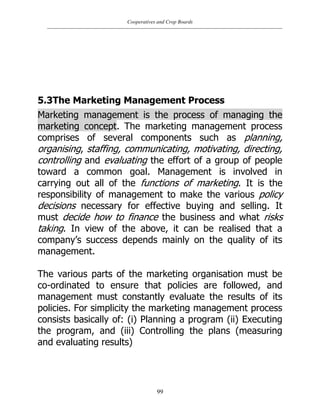

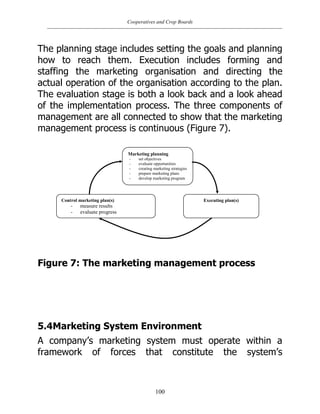

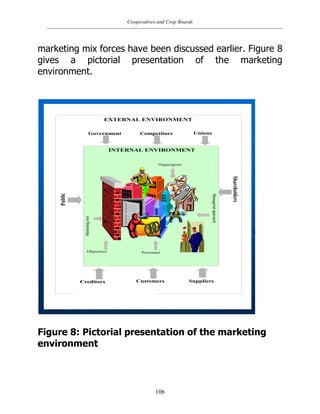

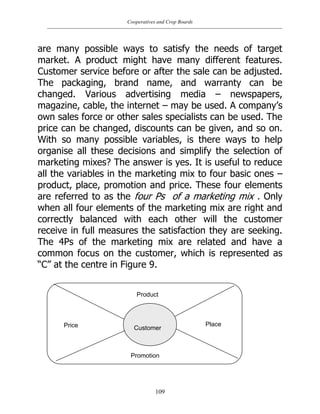

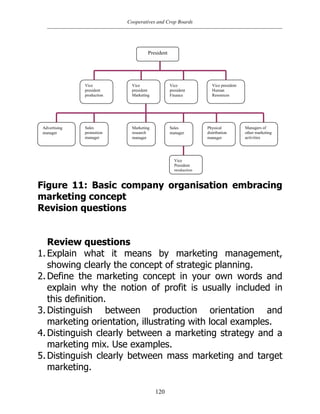

This document provides an introduction to marketing and agricultural marketing. It discusses key definitions of market and marketing, the historical development of marketing, approaches to studying marketing including commodity, functional and institutional approaches. It also outlines major classifications of goods marketed including consumer goods and industrial goods. The role of government and various institutions involved in agricultural marketing such as cooperatives and crop boards are introduced.