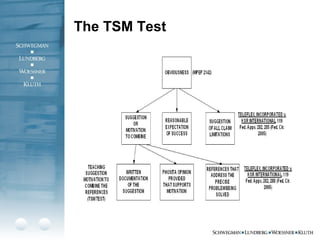

This document discusses obviousness under 35 U.S.C. 103(a) and how the standard for obviousness has evolved. It covers the Graham factors for determining obviousness, the rise of the teaching, suggestion, motivation test, and how KSR v. Teleflex found that test to be too rigid by disallowing the use of common sense. Post-KSR, examiners can use common sense in an obviousness analysis as long as the basis for concluding obviousness is not conclusory and has some articulated reasoning.

![Some Ways to Deal With

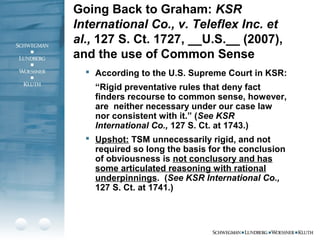

Obviousness Post-KSR

1. At least one claimed element is not

“familiar”/known/shown in the art.

2. The claimed invention is not a combination of discrete

elements at all.

3. The proposed combination of elements does not yield

the claimed invention.

4. At least one claimed element functions differently from

that in the prior art.

5. At least one claimed element was known only in

substantially unrelated area.

6. It would take ingenuity, beyond one of "ordinary skill in

the art," to combine elements. [Remembering that KSR

renders one of ordinary skill as omnificent, as expert as

any inventor.]

7. The number of alternative solutions for one claimed

element was large or infinite. [This attempts to overcome

a rejection on 'obvious to try.']

8. The result of the claimed combination would not have

been predictable, or would not have had a reasonable

expectation of success. [An unlikely sell without some

evidence to point to.]

9. Secondary considerations: long-felt but unsolved need;

commercial success; prior art expressions of doubt.

Note that KSR reaffirmed.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ObviousnessPostKSR-123239079619-phpapp01/85/Obviousness-Post-KSR-10-320.jpg)