This document provides an overview of narrative writing and the key elements to include in a narrative. It discusses the purpose of narrative writing, which is often to entertain or engage readers but can also be to share a personal experience or teach a lesson. It outlines important narrative elements like plot, characters, setting, and creative tension. It also discusses organizing a narrative using chronological, spatial, or dramatic order. The document provides guidance on developing key parts of a narrative like the thesis, plot, dialogue, and maintaining a clear narrative structure.

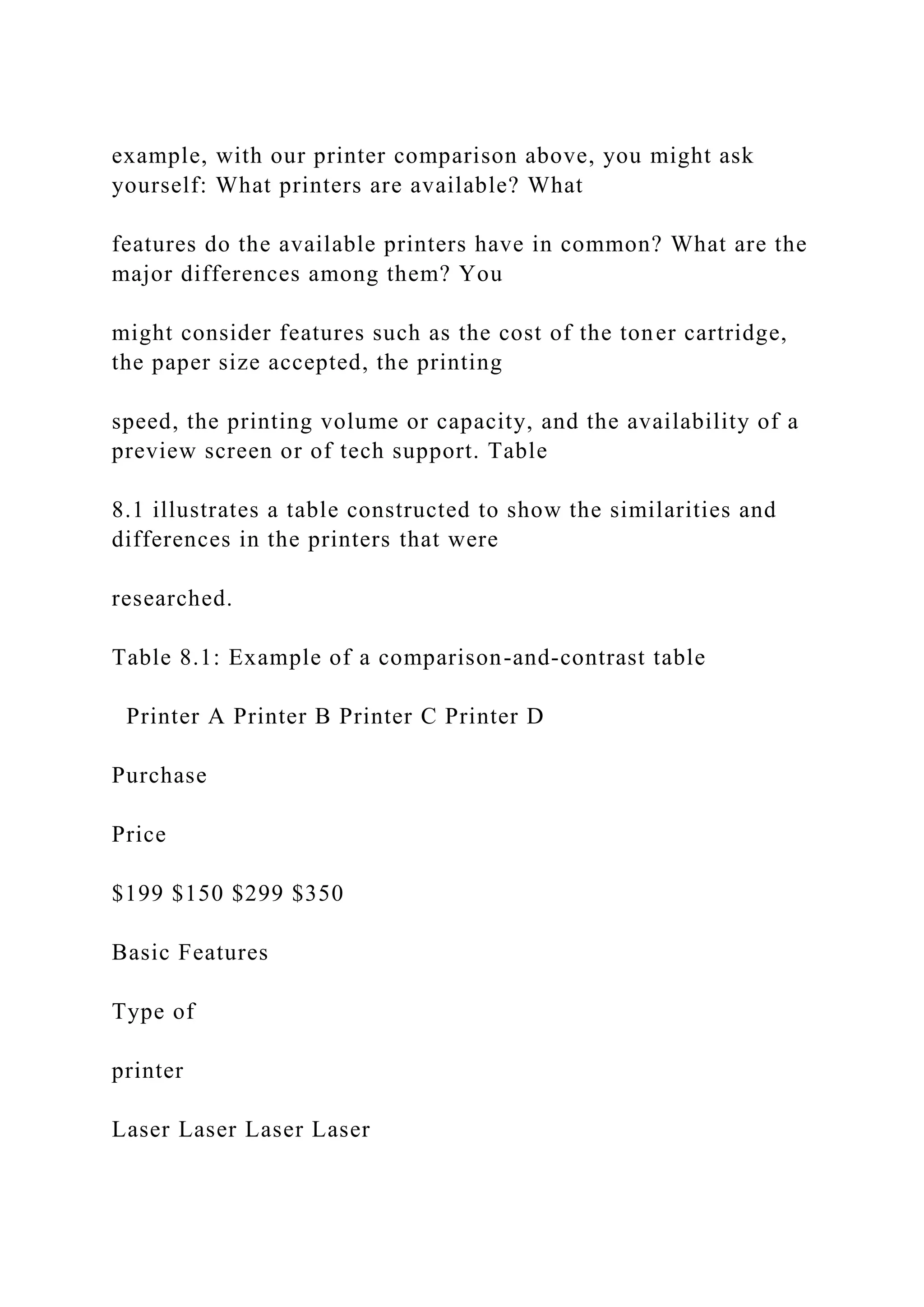

![these types of assignments. These assignments often require

taking a position on an issue and defending

it, proposing a solution to a problem or recommending a course

of action, evaluating the evidence a

writer presents to support his or her point of view, recognizing

errors in logic, or arguing a point of view.

Writing in Action: Examples of Persuasion and Argument

Writing Assignments

Key words and action verbs are underlined in the following

examples.

Write an eight-page paper in which you examine the practical,

ethical/social obligations; the need for

appropriate actions; and the optimal ethical, decision-making

processes existing in one of the four

following topic areas: The Role of Government, The Role of

Corporations, Environmental Issues, or

Ethical Integrity. [Expository] You must use at least five (5)

scholarly outside sources [Research] in

constructing your argument. [Argument]

Write a persuasive paper in which you state what you believe to

be the most pressing economic

problem facing our country today and what you believe should

be done to solve this problem.

[Persuasion]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/6-221108012159-f16c4a42/75/6-3-Narrative-Writing-Pattern-Narration-is-storytelling-f-docx-52-2048.jpg)

![Write an eight-page paper about a real contemporary problem

where you see the status quo as lined up

against something that is just or in favor of something that is

unjust. Make a case for what you think

would be just and argue for measures that should be taken to

counteract that injustice. Justify the

measures you propose. If you can make this assignment about

your own experience or community, then

all the better—but you must support your arguments and use at

least 8 to 10 outside sources in your

argument. [Argument]

Write an argumentative paper on one of the following topics.

Choose a topic where you can see at least

two points of view and present both points. If you feel so

strongly about a topic that you cannot see

another point of view, avoid writing about it. [Argument]

Suggested Topics

Should homosexual individuals be allowed the same rights that

heterosexuals have, such as marriage?

Should abortions be legal?

Are affirmative action laws fair?

Should America have stronger gun control laws?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/6-221108012159-f16c4a42/75/6-3-Narrative-Writing-Pattern-Narration-is-storytelling-f-docx-53-2048.jpg)

![Should assisted suicide be legal?

Are charter schools/vouchers detrimental to the American

educational system?

Should the death penalty be abolished?

Should animals be used in medical research?

Is global warming a genuine threat to the planet?

Should human cloning be legal?

Should embryonic stem cell research be federally funded?

Write a final research paper that focuses on a legal issue or

situation related to a business environment

or activity that you have experienced or about which you have

knowledge. Include a detailed description

of the topic; an analytical discussion of the legal issues

involved, including examining the issue from

different viewpoints; and a discussion of ethical considerations.

Write a well-defined and logically stated

argument to support your position on the issue or situation.

Include five research sources in addition to

your text. [Argument]

Write a six- to eight-page paper in which you tackle a current,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/6-221108012159-f16c4a42/75/6-3-Narrative-Writing-Pattern-Narration-is-storytelling-f-docx-54-2048.jpg)

![controversial issue and use persuasion to

convince your audience that your position on the issue is

correct. Your paper should incorporate several

methods of persuasion in the hope of "proving your point" to

your instructor. Find a topic you feel

passionate about. The list below can help you with ideas that

may be appropriate for your paper. Some

topics to consider could be the following: [Persuasion]

Abortion

Capital punishment

Socialism

Gun control

Smoking/secondhand smoke

Stem cell research

Lowering the alcohol drinking age

Reinstituting the military draft

Home schooling

Corporal punishment in schools

Position Papers

A position paper is an essay in which you take a stand, or state](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/6-221108012159-f16c4a42/75/6-3-Narrative-Writing-Pattern-Narration-is-storytelling-f-docx-55-2048.jpg)

![using second person (you, your). However, when you write

information that instructs someone how to

perform a task, you may use a second-person viewpoint (you) or

a viewpoint where the second person is

understood—for example, an instruction directed to the reader,

such as "[You] Open the folder."

Structure and Supporting Ideas

While expository papers generally follow the best practices laid

out in Chapter 5, the sections below give

additional details on how to structure a successful expository

paper.

Thesis Statement

Remember that, like all well-written papers, expository papers

must have a clear thesis. Make sure that

your paper has a focus and a primary idea you want to get

across to your readers. Here are some sample

expository thesis statements and stronger, revised versions of

each:

First draft thesis: Many factors contributed to the rise of the

suburbs, especially the development of the

automobile.

Revised thesis: The development of commuter trains and the

automobile, along with the desire for](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/6-221108012159-f16c4a42/75/6-3-Narrative-Writing-Pattern-Narration-is-storytelling-f-docx-130-2048.jpg)