The document discusses the importance of firm-specific knowledge and innovation strategies for competitive success in business, arguing that an incremental approach to strategy is more effective in dynamic and uncertain environments than a rationalist approach. It critiques traditional strategic planning models for their inability to adapt to rapidly changing conditions and emphasizes the need for continuous learning and adjustment. The authors advocate for a framework based on dynamic capabilities, highlighting the significance of aligning innovation with corporate strategy and understanding customer needs.

![According to Hamel and Prahalad, the concept of the corporation based on core competencies should

not replace the traditional one, but a commitment to it ‘will inevitably influence patterns of diversifica-

tion, skill deployment, resources allocation priorities, and approaches to alliances and outsourcing’

(1990, p. 86). More specifically, the conventional multidivisional structure may facilitate efficient innovation

D E V E L O P I N G A N I N N O VAT I O N S T R AT E G Y

1 9 8

www.managing-innovation.com

According to Christer Oskarsson:65

In the late 1950s . . . the time had come for Canon to apply its precision mechanical and

optical technologies to other areas [than cameras] . . . such as business machines. By 1964

Canon had begun by developing the world’s first 10-key fully electronic calculator . . . fol-

lowed by entry into the coated paper copier market with the development of an electrofax

copier model in 1965, and then into . . . the revolutionary Canon plain paper copier tech-

nology unveiled in 1968 . . . Following these successes of product diversification, Canon’s

product lines were built on a foundation of precision optics, precision engineering and

electronics . . .

The main factors behind . . . increases in the numbers of products, technologies and markets

. . . seem to be the rapid growth of information technology and electronics, technological transi-

tions from analogue to digital technologies, technological fusion of audio and video technologies,

and the technological fusion of electronics and physics to optronics (pp. 24–6).

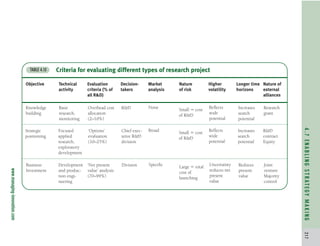

Two views of corporate structure: strategic business

units and core competencies

TABLE 4.9

Strategic business unit Core competencies

Basis for competition Competitiveness of today’s

products

Inter-firm competition to build com-

petencies

Corporate structure Portfolio of businesses in re-

lated product markets

Portfolio of competencies, core prod-

ucts and business

Status of business unit Autonomy: SBU ‘owns’ all re-

sources other than cash

SBU is a potential reservoir of core

competencies

Resource allocation SBUs are unit of analysis.

Capital allocated to SBUs

SBUs and competencies are unit of

analysis. Top management allocates

capital and talent

Value added of top

management

Optimizing returns through

trade-offs among SBUs

Enunciating strategic architecture, and

building future competencies

c04.qxd 2/9/09 4:26 PM Page 198](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-240728074444-2fd6e3c0/85/4-Chapter-4-Developing-an-Innovation-Strategy-pdf-35-320.jpg)

![• amongst different strategic objectives of the corporation, which include not only the establishment of

a distinctive advantage in existing businesses (involving both core and background technologies), but

also the exploration and establishment of new ones (involving emerging technologies).

(c) Core rigidities? As Dorothy Leonard-Barton has pointed out, ‘core competencies’ can also

become ‘core rigidities’ in the firm, when established competencies become too dominant.72 In addition

to sheer habit, this can happen because established competencies are central to today’s products, and

because large numbers of top managers may be trained in them. As a consequence, important new

competencies may be neglected or underestimated (e.g. the threat to mainframes from mini- and micro-

computers by management in mainframe companies). In addition, established innovation strengths may

overshoot the target. In Box 4.4, Leonard-Barton gives a fascinating example from the Japanese automo-

bile industry: how the highly successful ‘heavyweight’ product managers of the 1980s (see Chapter 9)

overdid it in the 1990s. Many examples show that, when ‘core rigidities’ become firmly entrenched,

their removal often requires changes in top management.

Developing and sustaining competencies

The final question about the notion of core competencies is very practical: how can management iden-

tify and develop them?

Definition and measurement. There is no widely accepted definition or method of measurement of

competencies, whether technological or otherwise. One possible measure is the level of functional

D E V E L O P I N G A N I N N O VAT I O N S T R AT E G Y

2 0 2

www.managing-innovation.com

Heavyweight product managers and fat product designs

BOX 4.4

Some of the most admired features . . . identified . . . as conveying a competitive advantage [to

Japanese automobile companies] were: (1) overlapping problem solving among the engineering and

manufacturing functions, leading to shorter model change cycles; (2) small teams with broad task

assignments, leading to high development productivity and shorter lead times; and (3) using a

‘heavyweight’ product manager – a competent individual with extensive project influence . . . who

led a cohesive team with autonomy over product design decisions. By the early 1990s, many of

these features had been emulated . . . by US automobile manufacturers, and the gap between US

and Japanese companies in development lead time and productivity had virtually disappeared.

However . . . there was another reason for the loss of the Japanese competitive edge – ‘fat prod-

uct designs’ . . . an excess in product variety, speed of model change, and unnecessary options . . .

‘overuse’ of the same capability that created competitive advantages in the 1980s has been the

source of the new problem in the 1990s. The formerly ‘lean’ Japanese producers such as Toyota had

overshot their targets of customer satisfaction and overspecified their products, catering to a long

‘laundry list’ of features and carrying their quest for quality to an extreme that could not be cost-

justified when the yen appreciated in 1993 . . . Moreover, the practice of using heavyweight man-

agers to guide important projects led to excessive complexity of parts because these powerful indi-

viduals disliked sharing common parts with other car models.

Source: Leonard-Barton, D. (1995) Wellsprings of Knowledge, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA, p. 33.

c04.qxd 2/9/09 4:26 PM Page 202](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-240728074444-2fd6e3c0/85/4-Chapter-4-Developing-an-Innovation-Strategy-pdf-39-320.jpg)