The document describes the 8th edition of 'Business Communication: In Person, In Print, Online,' emphasizing the evolution of communication in the digital workplace. It highlights the importance of effective written and oral communication, the integration of social media into business practices, and the shift from one-way to interactive communication. The text offers real-world examples and online resources to enhance learning and skill-building for students preparing for modern business challenges.

![Understand how to communicate

ethically and avoid legal consequences

of communication.

front of a jury about the content of this email I am about to

send?’ If the answer is

anything other than an unqualifi ed ‘yes,’ it is not an email that

should be sent.”40

You might ask yourself the same question for all

communications related to your

company.

ETHICS AND COMMUNICATION

Beyond the legal requirements, companies will expect you to

communicate ethi-

cally. Consider this situation: Brian Maupin, a Best Buy

employee, posted videos

about the company on YouTube.41 His fi rst cartoon video,

which received over

3.3 million views within two weeks, mocked a customer of

“Phone Mart,” desperate

for the latest version of the iPhone (Figure 12).

Before Maupin was invited back after being suspended, he

created another

video poking fun at the company’s policies. This interaction,

between the store

employee and the woman who “run[s] the ethics department” at

the corporate

offi ce, illustrates gray areas in communication ethics—and the

importance of

social media policies.

Was Maupin’s behavior ethical? Most corporate executives

would consider the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3316800fmpi-xxxiiise-221224064856-15b24cb8/75/33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_SE-indd-xxx33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_S-docx-11-2048.jpg)

![mmeeeett aanndd tthhaannkk yyoouu

aaggaaiinn iinn ppeerrssoonn.. IInn tthhee

mmeeaannttiimmee,, pplleeaassee lleett mmee kknnooww

iiff yyoouu hhaavvee aannyy ssuuggggeessttiioonnss ffoorr

uuss,, aass wwee aarree ccoonnttiinnuuoouussllyy

ttrryyiinngg ttoo iimmpprroovvee..

BBeesstt wwiisshheess,,

JJiillll ZZeeffffeerrss

[email protected]@ssppaass..ccoomm

XXYYZZ SSppaass && SSaalloonnss

Thanks for at least

using my name.

They really care

what I think.

Wow! You really read my review!

Reply Delete Block User

“What TO Do” – A simple and personal thank you

Figure 13

Yelp’s Advice to Managers for Responding to a Positive

Customer Post

The Plymouth manager’s response (at the bottom of Figure 12)

could be more

substantive, but her response is brief and funny. For informal](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3316800fmpi-xxxiiise-221224064856-15b24cb8/75/33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_SE-indd-xxx33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_S-docx-20-2048.jpg)

![Art Director: Stacy Shirley

Rights Acquisitions Specialist: Sam Marshall

Senior Rights Acquisitions Specialist: Deanna

Ettinger

Photo Researcher: Terri Miller/E-Visual

Communications, Inc.

Printed in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 15 14 13 12 11

For product information and technology assistance, contact us at

Cengage Learning Customer & Sales Support, 1-800-354-9706

For permission to use material from this text or product,

submit all requests online at www.cengage.com/permissions

Further permissions questions can be emailed to

[email protected]

33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_SE.indd xvi33168_00_fm_pi-

xxxiii_SE.indd xvi 14/12/11 5:47 PM14/12/11 5:47 PM

www.cengage.com/permissions

www.cengage.com

www.cengagebrain.com

xvii

Brief Contents

PART 1

FOUNDATIONS OF BUSINESS COMMUNICATION](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3316800fmpi-xxxiiise-221224064856-15b24cb8/75/33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_SE-indd-xxx33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_S-docx-54-2048.jpg)

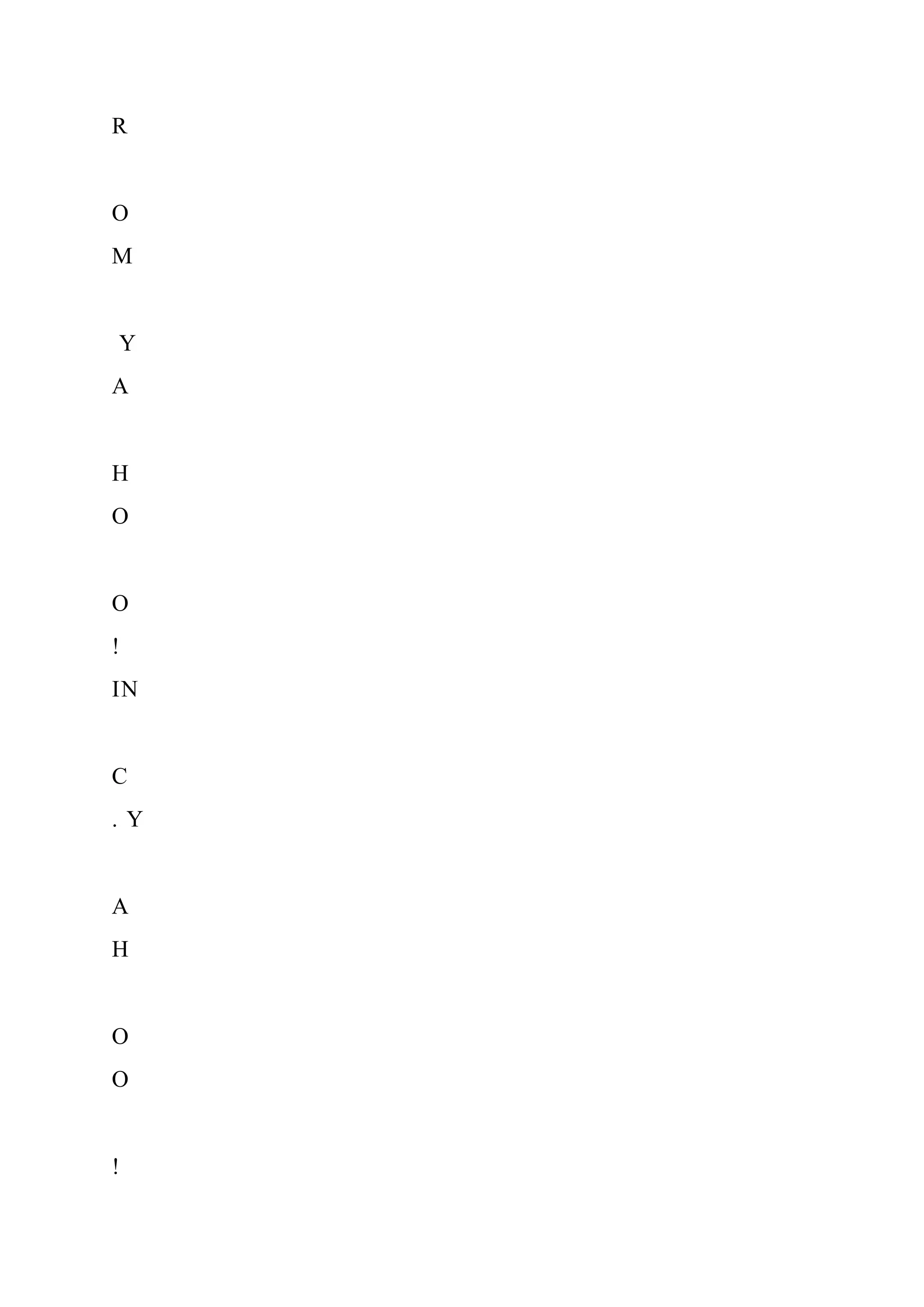

![SVP, Southeast

Plains Division

Cos LaPorta

SVP, Western

Paci�c Division

Chris Carr

SVP, Northwest

Mountain Division

Cliff Burrows

President, Starbucks

Coffee U.S.

John Culver

President, Starbucks

Coffee International

Annie Young-Scrivner

Chief Marketing Of�cer

Troy Alstead

EVP, Chief Financial

Of�cer and Chief

Administrative Of�cer

[and others]

Howard Schultz

CEO & President

Figure 3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3316800fmpi-xxxiiise-221224064856-15b24cb8/75/33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_SE-indd-xxx33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_S-docx-111-2048.jpg)

![anything other than an unqualifi ed ‘yes,’ it is not an email that

should be sent.”40

You might ask yourself the same question for all

communications related to your

company.

ETHICS AND COMMUNICATION

Beyond the legal requirements, companies will expect you to

communicate ethi-

cally. Consider this situation: Brian Maupin, a Best Buy

employee, posted videos

about the company on YouTube.41 His fi rst cartoon video,

which received over

3.3 million views within two weeks, mocked a customer of

“Phone Mart,” desperate

for the latest version of the iPhone (Figure 12).

Before Maupin was invited back after being suspended, he

created another

video poking fun at the company’s policies. This interaction,

between the store

employee and the woman who “run[s] the ethics department” at

the corporate

offi ce, illustrates gray areas in communication ethics—and the

importance of

social media policies.

Was Maupin’s behavior ethical? Most corporate executives

would consider the

videos disparaging to the company. Although Maupin didn’t

expect the videos to

be such a huge success, he still publicly disagreed with sales

policies, questioned

loyalty to a top Best Buy supplier (Apple), and insulted

customers. Things worked](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3316800fmpi-xxxiiise-221224064856-15b24cb8/75/33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_SE-indd-xxx33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_S-docx-170-2048.jpg)

![Messaging,” Pew Internet &

American Life Project, September

2004, www.pewinternet.org/

Reports/2004/How-Americans-Use-

Instant-Messaging.aspx, accessed

July 29, 2009.

23. Gartner, “Hype Cycle for Emerging

Technologies, 2008 [ID Number:

G00159496],” www.gartner

.com/technology/research/

methodologies/hypeCycles.jsp,

accessed May 20, 2009.

24. “Ten Ways to Use Texting for Busi-

ness,” Inc.com, www.inc.com/ss/

ten-ways-use-texting-business,

accessed July 12, 2010.

25. “Social Media in Business: Fortune

100 Statistics,” iStrategy 2010 with

data from Burson-Marsteller, June 7,

2010, http://misterthibodeau

.posterous.com/istrategy-2010-blog-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3316800fmpi-xxxiiise-221224064856-15b24cb8/75/33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_SE-indd-xxx33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_S-docx-218-2048.jpg)

![How the feedback will work: “When you [do this], I feel [this

way], because [of

such and such].” (Pause for discussion.) “What I would like you

to consider is

[doing X], because I think it will accomplish [Y]. What do you

think?”

Example: “When you submit work late, I get angry because it

delays the rest of

the project. We needed your research today in order to start the

report outline.”

(Pause for discussion.) “I’d like you to consider fi nding some

way to fi nish work

on time, so we can be more productive and meet our tight

deadlines. What do

you think?”

©

C

E

N

G

A](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3316800fmpi-xxxiiise-221224064856-15b24cb8/75/33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_SE-indd-xxx33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_S-docx-255-2048.jpg)

![Griffi n Draft company overview section (mission,

vision, etc.).

April 24

Beata Draft management profi les. April 24

Madeline Research local ice cream shops and other

businesses for competitive analysis section.

April 30

[To be continued . . .]

Figure 5

Example of a

Simple Project Plan

Figure 4 Steps for Team Writing

©

C](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3316800fmpi-xxxiiise-221224064856-15b24cb8/75/33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_SE-indd-xxx33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_S-docx-263-2048.jpg)

![up is. Will you

give me the item number?

Caller: [Sigh] Okay, it’s 330506558696.

Me: Thank you. I’ll be with you in just a minute.

[pause]

Me: Okay, is this Mr. Espinosa?

Caller: Yes.

Me: Mr. Espinosa, I see that your payment went through PayPal

just yesterday.

[pause]

Caller: Well, I was out of town for a while, but I still need them

by tomorrow!

Me: I understand that you’re on a tight deadline now. Have you

contacted the

seller to see whether she can send the boots by express mail?

That might](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3316800fmpi-xxxiiise-221224064856-15b24cb8/75/33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_SE-indd-xxx33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_S-docx-557-2048.jpg)

![Revise for content, style, and correctness.

Proofread your message.

“This [company]

sign is both

disappointing and

anti-social.”

— CAREY ALEXANDER,

THE CONSUMERIST, ABOUT POORLY

WRITTEN RESTAURANT SIGN

ience Analysis (4 ce? (4) What Is

104

33168_04_ch04_p104-139.indd 10433168_04_ch04_p104-

139.indd 104 09/12/11 10:12 AM09/12/11 10:12 AM

105](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3316800fmpi-xxxiiise-221224064856-15b24cb8/75/33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_SE-indd-xxx33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_S-docx-611-2048.jpg)

![Team, who created a beautiful representation of Aggresshop’s

most unique clothing

and accessories.

You will receive 100 copies of the catalog in your store by

February 20. If you would

like more than 100 copies, please contact Maryanne

([email protected]) by

Friday, February 15.

Catalogs will be shipped to customers on February 22—one

week earlier this year in

response to your requests.

Best of luck for a successful spring season.

Is printed on paper with

a company logo.

Includes standard

memo heading with

the writer’s initials.

Refers to attached printed

materials (a good reason to](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3316800fmpi-xxxiiise-221224064856-15b24cb8/75/33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_SE-indd-xxx33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_S-docx-695-2048.jpg)

![improve the well-being of people of all ages through innovative

and effective programs

that enable everyone to learn, work, and thrive.

Winter Family Day helped everyone beat the winter blues while

introducing new friends

to all that Parents Place has to offer. For more information on

Parents Place, please

call 914-948-5187 or email [email protected]

Sincerely,

Laura Newman

Director of Development

Includes the organization’s

logo at the top, typically

placed at left or centered.

Uses block letter format,

with the date and receiver’s

address aligned left.

Uses the standard](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3316800fmpi-xxxiiise-221224064856-15b24cb8/75/33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_SE-indd-xxx33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_S-docx-699-2048.jpg)

![Although closely related, unity and coherence are not the same.

A paragraph has

unity when all its parts work together to develop a single idea

consistently and

logically. A paragraph has coherence when each sentence links

smoothly to the

sentences before and after it.

Unity

A unifi ed paragraph gives information that is directly related to

the topic, pres-

ents this information in a logical order, and omits irrelevant

details. The fol-

lowing excerpt is a middle paragraph in a memo arguing

against the proposal

that Collins, a baby-food manufacturer, should expand into

producing food for

adults:

NOT [1] We cannot focus our attention on both ends of the age

spectrum.

[2] In a recent survey, two-thirds of the under-35 age group

named

Collins as the fi rst company that came to mind for the category

“baby-food products.” [3] For more than 50 years, we have](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3316800fmpi-xxxiiise-221224064856-15b24cb8/75/33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_SE-indd-xxx33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_S-docx-853-2048.jpg)

![spent

millions of dollars annually to identify our company as the

baby-food

company, and market research shows that we have been success-

ful. [4] Last year, we introduced Peas ‘n’ Pears, our most

successful

baby-food introduction ever. [5] To now seek to position

ourselves as

a producer of food for adults would simply be incongruous. [6]

Our

well-defi ned image in the marketplace would make producing

food

for adults risky.

Before reading further, rearrange these sentences to make the

sequence of

ideas more logical. As written, the paragraph lacks unity. You

may decide that the

overall topic of the paragraph is Collins’ well-defi ned image as

a baby-food pro-

ducer. So Sentence 6 would be the best topic sentence. You

might also decide that

Sentence 4 brings in extra information that weakens paragraph

unity and should

be left out. The most unifi ed paragraph, then, would be](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3316800fmpi-xxxiiise-221224064856-15b24cb8/75/33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_SE-indd-xxx33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_S-docx-854-2048.jpg)

![3. Daniel M. Oppenheimer,

“Consequences of Erudite

Vernacular Utilized Irrespective

of Necessity: Problems with Using

Long Words Needlessly,” Applied

Cognitive Psychology, vol. 20,

pp. 139–156 (2006). Quoted in

Richard Morin, “Nerds Gone Wild,”

The 2006 Ig Nobel Awards, Pew

Center Research Publications,

October 6, 2006, http://pewresearch

.org/pubs/72/nerds-gone-wild,

accessed October 23, 2010.

4. Dave Zinczenko and Matt Goulding,

“The 5 Worst Kids’ Meals in

America,” July 23, 2010, http://today

.msnbc.msn.com/id/38367754/ns/

today-today_health/t/worst-

kids-meals-america/, accessed

July 30, 2010.

5. “What Silly Sounding Business

Jargon Do You Have to Hear al [sic]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3316800fmpi-xxxiiise-221224064856-15b24cb8/75/33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_SE-indd-xxx33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_S-docx-963-2048.jpg)

![[the

industry].” For example, Apple has been referred to as the

“Nordstrom

of Technology” for its attention to customers.2

Nordstrom’s approach is low tech and personal. The Nordstrom

Way,

a book about Nordstrom’s service culture, describes sales

associ-

ates’ relationships with customers. In one example, a customer

at

the Michigan Avenue store in Chicago told a salesperson, “I

love the

coat, but it’s way too expensive. But if it ever goes on sale, will

you please let me know.” The salesperson made a note, called

the cus-

tomer when the price dropped, and shipped the coat to her. This](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3316800fmpi-xxxiiise-221224064856-15b24cb8/75/33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_SE-indd-xxx33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_S-docx-970-2048.jpg)

![followed by explanations

and details.

First determine whether

a written message is

needed.

Compose a neutral

message.

33168_06_ch06_p180-207.indd 18233168_06_ch06_p180-

207.indd 182 09/12/11 12:18 PM09/12/11 12:18 PM

CHAPTER 6 Neutral and Positive Messages 183

Contact

Shannon Lammert Jill Saunders

314-423-8000 ext. 5379 314-423-8000 ext. 5293

314-556-8841 (cell) 314-422-4523 (cell)

[email protected][email protected]

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3316800fmpi-xxxiiise-221224064856-15b24cb8/75/33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_SE-indd-xxx33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_S-docx-977-2048.jpg)

![arrangements.

Thanks again for your inquiry, and I hope to speak with you

soon. You can call

me at (215) 555-6760 or email me at [email protected]

Sincerely,

Ron Ramone

Enclosure

Immediately addresses the

customer’s inquiry about a

function on a specific date.

S

OU

THSIDE

BREWER

Y

Includes the standard

letter salutation.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3316800fmpi-xxxiiise-221224064856-15b24cb8/75/33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_SE-indd-xxx33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_S-docx-1014-2048.jpg)

![bbiirrtthhddaayy ssppeecciiaall..

PPlleeaassee ffeeeell ffrreeee ttoo aasskk ffoorr mmee iiff

aanndd wwhheenn yyoouu aarree nneexxtt ccoommiinngg

iinn——iitt wwoouulldd bbee mmyy pplleeaassuurree ttoo

mmeeeett aanndd tthhaannkk yyoouu

aaggaaiinn iinn ppeerrssoonn.. IInn tthhee

mmeeaannttiimmee,, pplleeaassee lleett mmee kknnooww

iiff yyoouu hhaavvee aannyy ssuuggggeessttiioonnss ffoorr

uuss,, aass wwee aarree ccoonnttiinnuuoouussllyy

ttrryyiinngg ttoo iimmpprroovvee..

BBeesstt wwiisshheess,,

JJiillll ZZeeffffeerrss

[email protected]@ssppaass..ccoomm

XXYYZZ SSppaass && SSaalloonnss

Thanks for at least

using my name.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3316800fmpi-xxxiiise-221224064856-15b24cb8/75/33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_SE-indd-xxx33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_S-docx-1055-2048.jpg)

![1850 East Camelback Road,

Phoenix, AZ 85017) wants to know especially about your ability

to work well with others.

Compose (but do not send) an email message to Dr. Thavinet

([email protected]

.edu), asking for a letter of recommendation. You would like

him to respond within two

weeks.

Compose a neutral

message.

SSuummmmmmaarrry

EExxeercciiseesss

33168_06_ch06_p180-207.indd 20033168_06_ch06_p180-

207.indd 200 09/12/11 12:19 PM09/12/11 12:19 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3316800fmpi-xxxiiise-221224064856-15b24cb8/75/33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_SE-indd-xxx33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_S-docx-1072-2048.jpg)

![HCD RESEARCH, INC. OWNS THE COPYRIGHT TO THESE

IMAGES AS PRESENTED, BUT THE GRAPH DEVELOPED

BY MEDIA-

CURVES.COM, AN HCD RESEARCH OWNED WEBSITE, IS

SET AGAINST PICTURES OWNED BY [TOYOTA IN THE

CASE OF IMAGE 1,

CBS NEWS IN THE CASE OF IMAGE 2, AND THE MATTEL,

INC. IN THE CASE OF IMAGE 3] AND EMPLOYED BY HCD

AS FAIR USE TO

PERFORM ITS ANALYSIS AND CREATE A NEW WORK.

deo shows Jim

.

33168_07_ch07_p208-247.indd 20933168_07_ch07_p208-

247.indd 209 09/12/11 11:08 AM09/12/11 11:08 AM

PART 3 Written Messages210

PLANNING PERSUASIVE MESSAGES

We use persuasion to motivate someone to do something or](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3316800fmpi-xxxiiise-221224064856-15b24cb8/75/33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_SE-indd-xxx33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_S-docx-1109-2048.jpg)

![have an idea for an innovative gift, please contact Martina

Emmerson at

404.894.0274 or at [email protected]

I appreciate your support and honor your continued involvement

with

the ECE family of faculty, students, staff, and alumni.

Best regards,

Gary S. May,

Professor and Steve W. Chaddick School Chair

Last revised on April 23, 2010

+ About ECE

+ Academics

+ Academic

Enrichment

+ Research

+ Faculty & Staff](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3316800fmpi-xxxiiise-221224064856-15b24cb8/75/33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_SE-indd-xxx33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_S-docx-1271-2048.jpg)

![saying goodbye to colleagues and friends is never easy. they all

are

dedicated members of our yahoo! family, who worked beside us

and

shared our passion.

One study identified three main reasons employees found the

use of

lowercase inappropriate:

• Demonstrated a poor choice for Yang’s position as CEO and

for the negative message

• Indicated a lack of respect for employees

• Left a negative impression of Yang personally2

Employees’ comments, as in the following example, reflected

hurt

and anger: “[S]eriously, is a shift key too much to ask when

thou-

sands are losing their jobs?”3

To prepare managers for individual meetings with employees,

Yahoo!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3316800fmpi-xxxiiise-221224064856-15b24cb8/75/33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_SE-indd-xxx33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_S-docx-1303-2048.jpg)

![all messages

from employees be written using the direct plan.

• The reader expects a “no” response. Applicants for a popular

reality TV show

know that a letter (instead of a phone call) means bad news. An

indirect

plan in these cases only delays the inevitable rejection and may

anger the

receiver.

• The writer wants to emphasize the negative news. A forceful

“no” may

be in order if you’re rejecting a proposal a second time or

responding to

an unreasonable request (“Although Mr. Jackson [the CEO]

admires your

ambition, it isn’t appropriate for you, as an intern, to join his

dinner with the

Board of Directors on Wednesday”). Sometimes the news is too

important for

the reader to miss.

When a marketing company’s list of email addresses was stolen,

several of its](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3316800fmpi-xxxiiise-221224064856-15b24cb8/75/33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_SE-indd-xxx33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_S-docx-1320-2048.jpg)

![33168_09_ch09_p284-323.indd 32233168_09_ch09_p284-

323.indd 322 09/12/11 11:36 AM09/12/11 11:36 AM

CHAPTER 9 Planning the Report and Managing Data 323

1. “McDonald’s, The Marketing Pro-

cess,” The Times 100, 2006, www

.thetimes100.co.uk/downloads/

mcdonalds/mcdonalds_11_full.pdf,

accessed September 2, 2010.

2. Jillian Madison, “McDonalds [sic]

Menu Items from Around the

World,” Food Network Humor, July 9,

2009, http://foodnetworkhumor

.com/2009/07/mcdonalds-menu-

items-from-around-the-world-40-

pics/, accessed August 31, 2010.

3. “McDonald’s, The Marketing

Process.”

4. “McDonald’s, The Marketing](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3316800fmpi-xxxiiise-221224064856-15b24cb8/75/33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_SE-indd-xxx33168_00_fm_pi-xxxiii_S-docx-1665-2048.jpg)