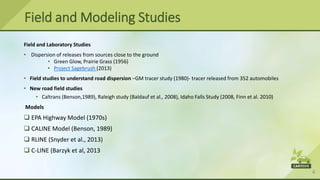

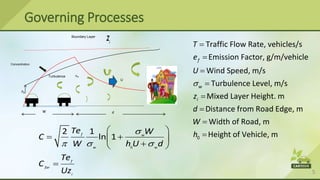

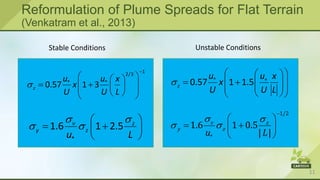

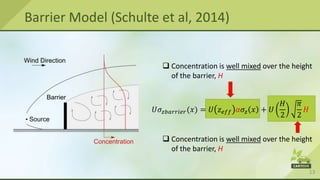

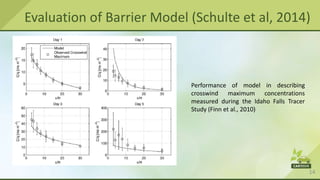

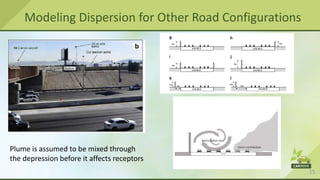

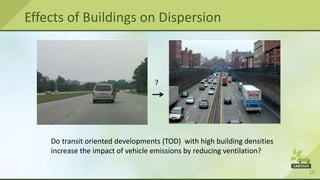

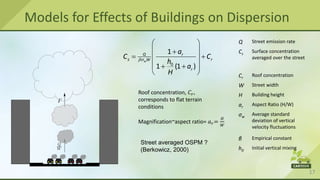

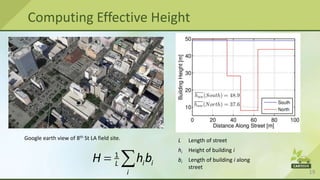

1. The document discusses methods for modeling the dispersion of air pollutants from roadways using field studies, wind tunnel experiments, and computational models. It describes several models used to simulate dispersion under various conditions like stable/unstable atmospheric conditions, presence of barriers, and effects of buildings.

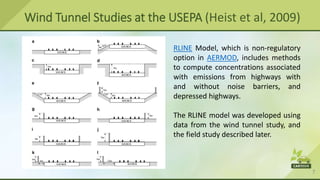

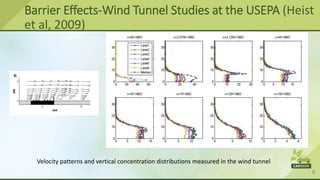

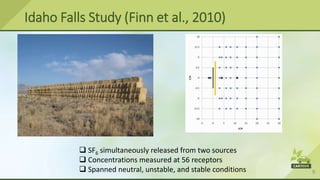

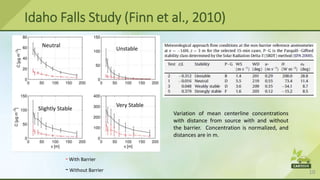

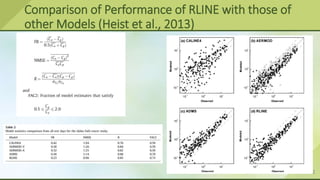

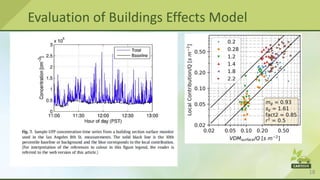

2. Recent field studies and wind tunnel experiments have provided data to develop and evaluate models like RLINE that estimate near-road pollutant concentrations. These models are now incorporated into frameworks to analyze impacts on air quality and public health.

3. Remaining challenges include improving models for situations like depressed roads, accounting for effects of vegetation barriers, pollutant chemistry, and micrometeorology in urban areas. Models also tend to over