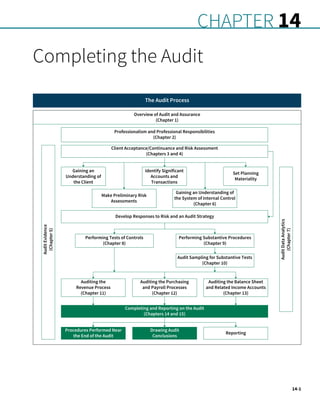

The document discusses procedures for completing an audit, including evaluating loss contingencies, subsequent events, and the going concern assumption. It describes how the audit team for Cloud 9 is preparing for a meeting with the partner by discussing final evidence evaluation, potential loss contingencies, subsequent event procedures, going concern assessment, and communication with the client's audit committee. The team needs to ensure the partner is fully briefed on any contentious issues before meetings with management and the audit committee.

![14-4 Chapter 14 Completing the Audit

determine if management’s assessment is reasonable, appropriate liabilities have been

recorded,

and the disclosures are complete. Auditors should carefully consider the completeness assertion

for loss contingencies. Management may not be sufficiently objective and could fail to identify

loss contingencies or may classify identified contingencies as remote to avoid accruing or disclos-

ing them. Failing to identify one or more material loss contingencies is a material misstatement.

During the execution of all phases of the audit, the audit team should be watchful for

evidence of any potential loss contingencies. Many of the risk assessment procedures used to

gain an understanding of the entity, the industry, and its environment may identify the possi-

bility of loss contingencies. Substantive procedures used when testing account balances and

classes of transactions may also bring to light potential loss contingencies. Illustration 14.1

provides examples of audit procedures used during risk assessment and/or risk response that

can reveal the potential risk for loss contingencies.

Toward the end of the audit, auditors perform an inquiry procedure specifically designed to

gather information about loss contingencies arising from litigation, claims, and assessments. Audi-

tors will communicate directly with the client’s external legal counsel by sending a letter of inquiry,

often referred to as a legal letter. If the client has in-house legal counsel responsible for litigation,

claims, and assessments, a legal letter will also be sent to the in-house legal counsel. Attorneys and

their clients have a privileged relationship. That means attorneys cannot talk about their client’s

cases to anyone without permission from the client. Therefore, before auditors can communicate

with the client’s legal counsel, client management must give permission to the attorneys to discuss

theircaseswiththeauditors.Theclientgrantspermissiontotheattorneysbysigningthelegalletter.

Legal letters are sent to all attorneys the client paid for legal services. AU-C 501 Audit

Evidence—Specific Considerations for Selected Items and AS 2505 Inquiry of a Client’s Lawyer

Concerning Litigation, Claims, and Assessments provide guidance for the content of the legal

letter. The objective of the legal letter is to gather audit evidence regarding the existence of

uncertainties arising from litigation, claims, and assessments; the time period in which the

cause for the legal action occurred; the probability of an unfavorable outcome for the client;

and an estimate of the potential loss. A legal letter used for the Cloud 9 audit is presented in

Illustration 14.2, followed by explanations of the bracketed numbers. The format and wording

of the letter is dictated by auditing standards, so all auditors will follow the same basic format.

legal letter an audit inquiry

sent to a client’s external and

in-house legal counsel to obtain

information about litigation,

assessments, and claims

[1] Cloud 9 Inc.

[2] March 1, 2023

[3] Smith, Day, Jones

18696 11th Street, Suite 5000

Seattle, WA 95686

To Legal Counsel:

[4] In connection with an audit of our financial statements as of January 31, 2023, and for the year

then ended, please furnish our auditors, WS Partners, P.O. Box 525, Seattle, WA 95688, with the

information requested below concerning contingencies involving matters with respect to which

you have devoted substantial attention on behalf of the company in the form of legal consultation

or representation.

ILLUSTRATION 14.2

Example of legal letter used

for Cloud 9 audit

ILLUSTRATION 14.1

Risk assessment and risk

response procedures that may

identify loss contingencies

Risk assessment and risk response procedures that can reveal the potential risk for loss

contingencies:

1. Confirming with financial institutions, including guarantees of debt of others.

2. Inspecting the minutes of board of directors’ meetings.

3. Inspecting contracts, leases, and correspondence from governmental agencies.

4. Inspecting tax returns and correspondence with the IRS.

5. Inquiring of management regarding the completeness of recorded liabilities.

6. Inquiring of client’s legal counsel.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/14audit-221213073655-036cba86/85/14-Audit-pdf-4-320.jpg)

![Audit Procedures for Loss Contingencies 14-5

Sections of the letter in Illustration 14.2 are numbered to correspond with the following

explanations:

1.

Client letterhead—The legal letter is prepared on the client’s letterhead because the client

must grant permission for the attorneys to respond. Auditors oversee the preparation and

content of the letter and have control over the mailing and receipt of the letter.

2.

Date of the letter—The letter is sent about mid-way through the completion of year-end

fieldwork.

3.

Name and address of attorneys—A legal letter should be sent to all attorneys the client

hired during the year for legal services. Auditors can obtain a listing by inspecting the

transactions and invoices related to the client’s legal services expense account.

4.

Request for information—This paragraph identifies the financial statements under audit

and states a request to supply information directly to the auditors.

5.

Response regarding pending or threatened litigation—This paragraph requests that the

attorneys provide a list and description of pending or threatened litigation, claims, and

assessments. Notice auditors are seeking the attorney’s evaluation of the likelihood of an

unfavorable outcome and an estimate, if possible, of the potential loss.

6.

Response regarding unasserted claims or assessments—This paragraph requests that the

attorneys confirm their responsibility to inform management of situations that may in-

volve possible unasserted claims or assessments that may require disclosure. Notice the

reference to the applicable financial reporting framework, which for Cloud 9 is GAAP.

7.

Time frame for preparing the response—This paragraph specifies the time parameters for

the attorney’s response. The response should include matters that existed at January 31,

2023, and any matters after year-end up to the date of the attorney’s response letter. Ide-

ally, the date of the attorney’s response should coincide with the end of fieldwork, in this

case March 15, 2023, or very close to that date. Also, this paragraph requests the attorneys

state any reasons for limitations on their response.

8. Signature—The letter is signed by the client’s chief executive officer.

Source: AU-C 501.A69 and AS 2505A.

[5] Regarding pending or threatened litigation, claims, and assessments, please include in your

response: (1) the nature of each matter, (2) the progress of each matter to date, (3) how the Com-

pany is responding or intends to respond (for example, to contest the case vigorously or seek an

out-of-court settlement), and (4) an evaluation of the likelihood of an unfavorable outcome and an

estimate, if one can be made, of the amount or range of potential loss. Accordingly, please furnish

to our auditors such explanation, if any, that you consider necessary to supplement the foregoing

information, including an explanation of those matters for which your views may differ from those

of management.

[6] We understand that whenever, in the course of performing legal services for us with respect

to a matter recognized to involve an unasserted possible claim or assessment that may call for

financial statement disclosure, you have formed a professional conclusion that we should disclose

or consider disclosure concerning such possible claim or assessment, as a matter of professional

responsibility to us, you will so advise us and will consult with us concerning the question of such

disclosure and the applicable requirements of FASB ASC 450. Please specifically confirm to our

auditors that our understanding is correct.

[7] Your response should include matters that existed as of January 31, 2023, and during the period

from that date to the effective date of your response. Please specifically identify the nature of and

reasons for any limitations on your response. Our auditors expect to have the audit completed

about March 15, 2023. They would appreciate receiving your reply by that date with a specified

effective date no earlier than March 7, 2023.

Sincerely,

[8]James W. Harley

Chief Executive Officer

Cloud 9 Inc.

ILLUSTRATION 14.2

(continued)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/14audit-221213073655-036cba86/85/14-Audit-pdf-5-320.jpg)

![14-22 Chapter 14 Completing the Audit

a written statement by management provided to the auditor to confirm certain matters or

to support other audit evidence (AU-C 580.07). Generally, a written representation com-

plements other audit procedures that were performed and generally does not provide suf-

ficient appropriate audit evidence on its own. For example, auditors ask management for

a written representation that no material subsequent events have occurred that require

adjustment to or disclosure in the financial statements. That evidence does not relieve au-

ditors of their duty to perform audit procedures designed to identify subsequent events. The

written representation supplements the inquiries made of management regarding subse-

quent events and the evidence gathered from audit procedures related to subsequent events

identification.

As we have discussed throughout the text, auditors make many inquiries of manage-

ment during risk assessment, testing of internal controls, and performance of substantive

procedures. The responses to the inquiries are documented in the auditor’s working papers.

As supplemental evidence to the inquiries, auditors are required to obtain a management

representation letter as a final piece of audit evidence. A management representation letter

is a letter from management to the auditor acknowledging management’s responsibility for

the preparation of the financial statements and details of any verbal representations made by

management during the course of the audit. However, the management representation letter

is not a substitute for obtaining sufficient, appropriate evidence regarding the financial state-

ments through other audit procedures.

As you can imagine, the letter could be quite daunting to write because of the volume

of inquiries made of management during the audit. To help with this task, AU-C 580.A35

and AS 2805.16 provide illustrative management representation letters that auditors can

use as a guideline for what should be included in the letter. Illustration 14.12 contains a

management representation letter for the Cloud 9 audit. Since Cloud 9 is a public company,

the letter has been prepared using the example provided in PCAOB AS 2805.16.

management representation

letter a letter from manage-

ment to the auditor acknowledg-

ing management’s responsibility

for the preparation of the finan-

cial statements and details of any

verbal representations made by

management during the course of

the audit

[1] Cloud 9 Inc.

[2] March 15, 2023

[3] WS Partners

P.O. Box 525

Seattle, WA 95688

Dear WS Partners:

[4] We are providing this letter in connection with your audit of the consolidated financial state-

ments of Cloud 9 Inc. as of January 31, 2023, and for the year then ended for the purpose of ex-

pressing an opinion as to whether the consolidated financial statements present fairly, in all mate-

rial respects, the financial position, results of operations, and cash flows of Cloud 9 in conformity

with accounting principles generally accepted in the United States of America. We confirm that

we are responsible for the fair presentation in the consolidated financial statements of financial

position, results of operations, and cash flows in conformity with generally accepted accounting

principles.

[5] Certain representations in this letter are described as being limited to matters that are material.

Items are considered material, regardless of size, if they involve an omission or misstatement of

accounting information that, in the light of surrounding circumstances, makes it probable that the

judgment of a reasonable person relying on the information would be changed or influenced by

the omission or misstatement.

[6] We confirm, to the best of our knowledge and belief, as of March 15, 2023, the following repre-

sentations made to you during your audit:

1. The financial statements referred to above are fairly presented in conformity with accounting

principles generally accepted in the United States of America.

ILLUSTRATION 14.12

Management representation

letter for Cloud 9 audit](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/14audit-221213073655-036cba86/85/14-Audit-pdf-22-320.jpg)

![Management Representation and Communication with Those Charged with Governance 14-23

2.

We have made available to you all—

a.

Financial records and related data, including the names of all related parties and all rela-

tionships and transactions with related parties.

b.

Minutes of the meetings of stockholders, directors, and committees of directors, or

summaries of actions of recent meetings for which minutes have not yet been prepared.

3. There have been no communications from regulatory agencies concerning noncompliance

with or deficiencies in financial reporting practices.

4. There are no material transactions that have not been properly recorded in the accounting

records underlying the financial statements.

5. We believe that the effects of the uncorrected financial statement misstatements summarized

in the accompanying schedule are immaterial, both individually and in the aggregate, to the

financial statements taken as a whole.

6.

We acknowledge our responsibility for the design and implementation of programs and con-

trols to prevent and detect fraud.

7.

We have no knowledge of any fraud or suspected fraud affecting the entity involving—

a. Management,

b. Employees who have significant roles in internal control, or

c. Others where the fraud could have a material effect on the financial statements.

8.

We have no knowledge of any allegations of fraud or suspected fraud affecting the entity re-

ceived in communications from employees, former employees, analysts, regulators, short

sellers, or others.

9. The company has no plans or intentions that may materially affect the carrying value or clas-

sification of assets and liabilities.

10. The following have been properly recorded or disclosed in the financial statements:

a. Related party transactions, including sales, purchases, loans, transfers, leasing arrange-

ments, and guarantees, and amounts receivable from or payable to related parties.

b. Guarantees, whether written or oral, under which the company is contingently liable.

c.

Significant estimates and material concentrations known to management that are re-

quired to be disclosed in accordance with the FASB ASC Topic 275, Risks and Uncertainties.

[Significant estimates are estimates at the balance sheet date that could change materi-

ally within the next year. Concentrations refer to volumes of business, revenues, available

sources of supply, or markets or geographic areas for which events could occur that would

significantly disrupt normal finances within the next year.]

11. There are no—

a.

Violations or possible violations of laws or regulations whose effects should be

considered for disclosure in the financial statements or as a basis for recording a loss

contingency.

b.

Unasserted claims or assessments that our lawyer has advised us are probable of

assertion and must be disclosed in accordance with Financial Accounting Standards Board

(FASB) ASC Topic 450, Contingencies.

c.

Other liabilities or gain or loss contingencies that are required to be accrued or disclosed

by FASB ASC Topic 450.

d.

Side agreements or other arrangements (either written or oral) that have not been

disclosed to you.

12. The company has satisfactory title to all owned assets, and there are no liens or encumbranc-

es on such assets nor has any asset been pledged as collateral.

13. The company has complied with all aspects of contractual agreements that would have a ma-

terial effect on the financial statements in the event of noncompliance.

[7] To the best of our knowledge and belief, no events have occurred subsequent to the

balance-sheet date and through the date of this letter that would require adjustment to or

disclosure in the aforementioned financial statements.

James W. Harley

[8] Chief Executive Officer

David Collier

[8] Chief Financial Officer](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/14audit-221213073655-036cba86/85/14-Audit-pdf-23-320.jpg)