This document provides an overview of relational database concepts including:

- Relations are represented as tables with rows (tuples) and columns (attributes)

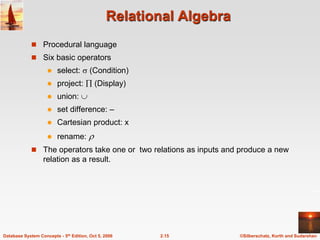

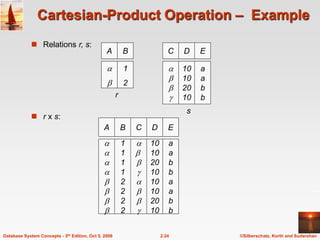

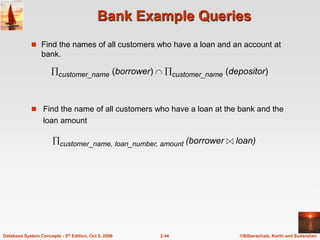

- Relations have a schema and can be queried using relational algebra which includes operations like select, project, join, and more

- Databases consist of multiple relations that store different parts of the information about an enterprise to avoid data repetition and null values

![©Silberschatz, Korth and Sudarshan

2.150

Database System Concepts - 5th Edition, Oct 5, 2006

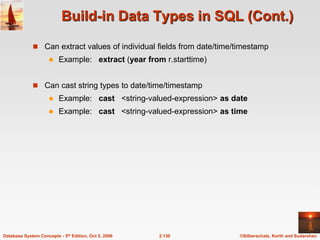

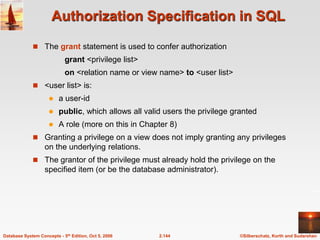

Dynamic SQL

Allows programs to construct and submit SQL queries at run time.

Example of the use of dynamic SQL from within a C program.

char * sqlprog = “update account

set balance = balance * 1.05

where account_number = ?”

EXEC SQL prepare dynprog from :sqlprog;

char account [10] = “A-101”;

EXEC SQL execute dynprog using :account;

The dynamic SQL program contains a ?, which is a place holder for a

value that is provided when the SQL program is executed.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/03relationaldatabases-230904052021-1d4e5319/85/03-Relational-Databases-ppt-150-320.jpg)