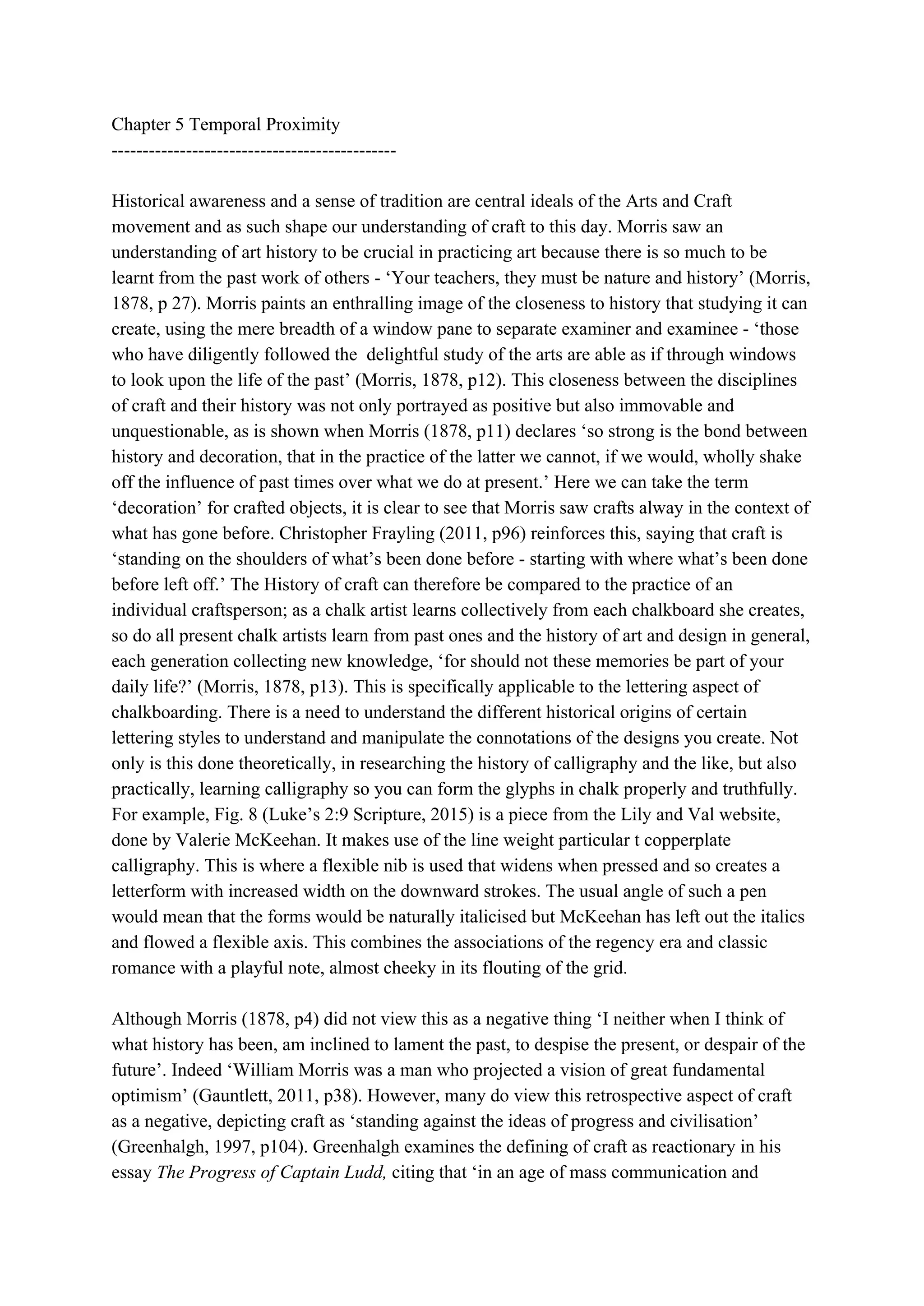

The document discusses the importance of history and tradition in craft. It argues that William Morris saw an understanding of art history as crucial for craftspeople, as there is much to be learned from past works. Morris believed the bond between history and craft was strong and inseparable. The document then discusses how some have viewed this retrospective aspect of craft negatively, as reactionary or against progress. However, it suggests this view has been perpetuated by misreadings between audiences and craft objects. With more people producing crafts through DIY culture and sharing skills online, it believes temporal closeness with history can be maintained.