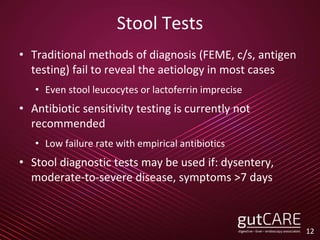

The document outlines updated guidelines on various gastrointestinal topics, including the management of Helicobacter pylori infections, acute diarrhea in adults, colorectal cancer screening, gallstone disease, and asymptomatic pancreatic cysts. Key recommendations are provided for testing, diagnosis, and treatment strategies, with an emphasis on evidence-based practices for primary care physicians. Overall, it highlights the importance of individualized patient care and adherence to the latest clinical standards.