ARTICULATION OF RESPONSE (CLARITY, ORGANIZATION, MECHANICS)The c.docx

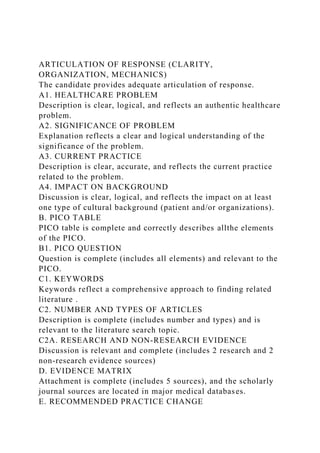

- 1. ARTICULATION OF RESPONSE (CLARITY, ORGANIZATION, MECHANICS) The candidate provides adequate articulation of response. A1. HEALTHCARE PROBLEM Description is clear, logical, and reflects an authentic healthcare problem. A2. SIGNIFICANCE OF PROBLEM Explanation reflects a clear and logical understanding of the significance of the problem. A3. CURRENT PRACTICE Description is clear, accurate, and reflects the current practice related to the problem. A4. IMPACT ON BACKGROUND Discussion is clear, logical, and reflects the impact on at least one type of cultural background (patient and/or organizations). B. PICO TABLE PICO table is complete and correctly describes allthe elements of the PICO. B1. PICO QUESTION Question is complete (includes all elements) and relevant to the PICO. C1. KEYWORDS Keywords reflect a comprehensive approach to finding related literature . C2. NUMBER AND TYPES OF ARTICLES Description is complete (includes number and types) and is relevant to the literature search topic. C2A. RESEARCH AND NON-RESEARCH EVIDENCE Discussion is relevant and complete (includes 2 research and 2 non-research evidence sources) D. EVIDENCE MATRIX Attachment is complete (includes 5 sources), and the scholarly journal sources are located in major medical databases. E. RECOMMENDED PRACTICE CHANGE

- 2. Explanation is clear, informs a practice change that addresses the PICO question, and is supported by the evidence. F1. KEY STAKEHOLDERS Explanation is congruent, logical, and addresses how to involve the 3 stakeholders in the decision F2. BARRIERS Description is relevant, includes specific barriers, and clearly applies the evidence. F3. STRATEGIES FOR BARRIERS identification is complete (includes 2 strategies) and is relevant to the barriers F4. INDICATOR TO MEASURE OUTCOME Indicator is relevant and measures the outcome. G. SOURCES The submission includes in-text citations and references and demonstrates a consistent application of APA style Help document A1. Healthcare Problem/ A2. Significance of Problem/ A3. Current Practice / A4. Impact on Background Write 1-2 paragraphs for each response. You may want to

- 3. include in text citations to support these sections. The A section should only discuss the problem without any mention of the intervention. The current practice should relate to the C in the PICO. Discussion on how the problem impacts either the workplace culture OR the patient's culture is required in A4. B. PICO Table (Chapter 4) Download the table from Taskstream or just include a 4 row by 2 column table in the paper and use the PICO toolkit as a guide (Module Video 2 and Toolkit, Appendix B). B1. PICO Question (Chapter 4) Construct the question that relates to the PICO elements in the table using the PICO Question Development toolkit as a guide (Module Video 2.4 and Toolkit, Appendix B). Here is a question template: Among (population), does (intervention) lower (problem) as compared to the current practice? C1. Keywords. This is just a list of the search terms used. C2. Number and Types of Articles. Describe the number and research types/subtypes of the articles you find in your search. They may include research articles, quality improvement, practice guidelines, pieces written to educate/inform, expert opinion, and more. This is a bare-bones description of the number and types of articles you find. For example, you might begin by stating the number of articles that came up (10,000) and the number you reviewed (20) then give a breakdown of the types you reviewed (5 RCT, 5 Reviews, 5 Quality Improvement projects, 5 Qualitative). (1 paragraph) C2a. Research and Non-Research Evidence. (Chapters 6 & 7). You can use 2 of your five research articles here to represent the 2 research studies. Be sure to state if the publication is a research or non-research evidence. Do not use an article with

- 4. the words systematic review or integrative review in the title as an example of non-research evidence. This will be 4 paragraphs describing the 2 research (Level I-III) and 2 non-research (Level IV-V) studies found during the search. Each paragraph should include the in-text citation for that article, for example: The first research study found … (Smith & Jones, 2014). Then write a few sentences about that research study and do the same for the other 3 articles. Review the research evidence appraisal toolkit and Chapter 6 for the research evidence articles. Review the non-research evidence appraisal toolkit and Chapter 7 for the non-research evidence articles. D. Evidence Matrix. Download the matrix from Taskstream. Enter the 5 research articles (Level I - III) in the table using the level and quality guide toolkit to determine the correct level. The research design/type should be quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods. Remember, level 1 are randomized controlled trials only, level 2 are quasi- experimental only, and everything else is level 3. For systematic and integrative reviews, read the level 1-3 definitions in Appendix C. The sample size for review studies are the number of articles reviewed. Please read chapter 6 & 7 and be sure not to include non research evidence such as quality improvement projects in the table (Module Video 3 Toolkit, Appendix C:Level and quality guide). E. Recommended Practice Change. This section should be a minimum of 6 sentences. The first sentence names the single intervention that all the articles in the matrix support. Then write one sentence each for the 5 studies in the matrix on how each article used the intervention to decrease the stated problem. Each of the five sentences must include an in text citation for that research study. For example, Intentional

- 5. rounding was shown to decrease falls by 20% over 3 months (Smith, Rogers, & Stein, 2014). (1-2 paragraphs) References Video for help with in text citations (2 minutes) F1. Key Stakeholders. (Chapter 3, p. 41 & Chapter 8, p. 155) A stakeholder is anyone who has something to win or lose from this change. Also, think about those whom you need to engage in the process to make it a lasting change by involving them in the decision to make the change. They can be floor nurses, nurse educators, nurse managers, nurse administrators, etc. You will need to mention at least 3 different key stakeholders. For each stakeholder, name a strategy to involve them in the decision to change the practice. (1-2 paragraphs) F2. Barriers. (Chapter 9, p. 177) This section is a discussion of the barriers to change. You may want to talk about change, delegation of tasks, training/education, funding, and attitude toward research as these are areas that cause barriers to initiation and continuing compliance with a practice change. Mention one barrier related to change and one barrier related to translation of research into practice. (1 paragraph) F3. Strategies for Barriers. (Chapter 9, p. 180) This section will discuss 2 strategies to overcome the identified barriers in section F2. (1 paragraph) F4. Indicator to Measure Outcome. (Chapter 1, p. 9 & Chapter 8, p. 154 - 155) An indicator is something that can be measured. For example, if the I in the PICO is “hourly rounding to prevent falls” the outcome measure would be the number of falls. Describe how you would measure an improvement after the practice change. (1 paragraph) G Sources. Remember to include 5 in-text citations in section E from the 5 research studies in the Evidence Matrix. Also, remember that the reference page should include all 7 studies

- 6. mentioned in the paper, assuming that the 2 research studies in C2a are also included in the 5 research studies in the Evidence Matrix. For reference page and in text citations: References rules A. Write a brief summary (suggested length of 2–3 pages) of the significance and background of a healthcare problem by doing the following: 1. Describe a healthcare problem. Note: A healthcare problem can be broad in nature or focused. 2. Explain the significance of the problem. 3. Describe the current practice related to the problem. 4. Discuss how the problem impacts the organization and/or patient’s cultural background (i.e., values, health behavior, and preferences). B. Complete the attached “PICO Table Template” by identifying all the elements of the PICO. 1. Develop the PICO question. C. Describe the search strategy (suggested length of 1–2 pages) you used to conduct the literature review by doing the following: 1. Identify the keywords used for the search. 2. Describe the number and types of articles that were available for consideration. a. Discuss two research evidence and two non-research evidence sources that were considered (levels I–V). Note: Be sure to upload a copy of the full text of the aritcles with your submission

- 7. D. Complete the attached “Evidence Matrix” to list five research evidence sources (levels I–III) from scholarly journal sources you locate in major medical databases. Note: Four different authors should be used for research evidence. Research evidence must not be more than five years old. Note: You may submit your completed matrix as a separate attachment to the task or you may include the matrix within your paper, aligned to APA standards. Note: Be sure to upload a copy of the full text of the articles with your submission. E. Explain a recommended practice change (suggested length of 1–3 pages) that addresses the PICO question within the framework of the evidence collected and used in the attached “Evidence Matrix.” F. Describe a process for implementing the recommendation from part E (suggested length of 2–3 pages) in which you do the following: 1. Explain how you would involve three key stakeholders in the decision to implement the recommendation. 2. Describe the specific barriers you may encounter in applying evidence to practice changes in the nursing practice setting. 3. Identify two strategies that could be used to overcome the barriers discussed in F2. 4. Identify one indicator to measure the outcome related to the recommendation. G. Acknowledge sources, using APA-formatted in-text citations and references, for content that is quoted, paraphrased, or summarized PICO Table

- 8. Example: P (patient/problem) Hospital acquired infection I (intervention/indicator) Handwashing C (comparison) Personal protective equipment, thorough physical assessments, proper room sanitization, private room O (outcome) Reduced infection Evidence Matrix Authors Journal Name/ WGU Library Year of Publication Research Design Sample Size Outcome Variables Measured Level (I–III) Quality (A, B, C) Results/Author’s Suggested Conclusions

- 10. Psychological Problems among aid workers oPerating in darfur Saif ali MuSa and abdalla a. R. M. HaMid United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain, United Arab Emirates Aid workers operating in war zones are susceptible to mental health problems that could develop into stress and acute traumatic stress. This study examined the relationships between burnout, job satisfaction (compassion satisfaction), secondary traumatic stress (compassion fatigue), and distress in 53 Sudanese and international aid workers in Darfur (mean age = 31.6 years). Measures used were the Professional Quality of Life Questionnaire (ProQOL; Stamm, 2005), the Relief Worker Burnout Questionnaire (Ehrenreich, 2001), and the General Health Questionnaire (Goldberg & Williams, 1991). Results showed that burnout was positively related to general distress and secondary traumatic stress, and negatively related to compassion satisfaction. Sudanese aid workers reported higher burnout and secondary traumatic stress than did international workers. Results are discussed in light of previous findings. It was concluded that certain conditions might increase aid workers’ psychological suffering and relief organizations need to create positive work climates through equipping aid workers with adequate training, cultural orientation, and psychological support services. Keywords: Darfur, burnout, distress, compassion satisfaction, secondary traumatic stress.

- 11. Sudan, the largest country in Africa, is located in northeast Africa. It is considered one of the least developed countries, and ranks 139 in the 2004 United Nations’ Development Program’s Human Development Index (UNDP, 2004). The Darfur region of western Sudan is composed of three states; north Darfur, SOCIAL BEHAVIOR AND PERSONALITY, 2008, 36 (3), 407- 416 © Society for Personality Research (Inc.) 407 Saif Ali Musa, PhD, Assistant Professor, Program of Social Work, United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain, United Arab Emirates; Abdalla A. R. M. Hamid, PhD, Associate Professor, Program of Psychology, United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain, United Arab Emirates. Appreciation is due to reviewers including: Taha Amir, PhD, and Hamzeh Dodeen, Department of Psychology, United Emirates University, P.O. Box 17851, Al Ain, United Arab Emirates, Email: [email protected] or [email protected] Please address correspondence and reprint requests to: Dr. Saif Ali Musa, Assistant Professor of the Social Work Program, United Arab Emirates University, P.O. Box 17771, Al Ain, United Arab Emirates. Phone: (971) 50 7134072; Fax: (971) 3 7671705; Email [email protected]; Dr. Abdalla Hamid, Associate Professor of the Psychology Program, United Arab Emirates University, P.O. Box 17771, Al Ain, United Arab Emirates. Phone: (971) 50

- 12. 7131 823; Fax: (971) 3 7670 453; Email: [email protected] PSYCHOLOGICAL PROBLEMS AMONG AID WORKERS408 west Darfur and south Darfur. These three states are 250,000 square kilometers in area with an estimated population of 6 million. The starting point of the armed conflict in Darfur region is typically said to be February 26, 2003 (Wikipedia, 2007). This conflict resulted in a complex humanitarian crisis which necessitated the intervention of both national and international aid agencies. Research on stress and mental health problems suffered by aid workers in their efforts to help traumatized individuals in prolonged complex emergency situations is scarce and still a new field (Adams, Boscarion, & Figley, 2006). The bulk of research has focused on the wellbeing of peacekeepers and armed personnel and traumatic events facing them (Cardozo et al., 2005). Aid workers operating in war zones encounter situations that are likely to generate more distress than would normal, everyday situations (Salama, 2007). They are susceptible to stress and acute traumatic stress (McFarlane, 2004) as a result of dealing with victims and being trapped in difficult situations. Health problems suffered by aid workers include physical

- 13. illnesses, psychological morbidity (such as distress, posttraumatic stress disorder, alcohol abuse, anxiety and depression), and even death (McFarlane, 2004). Other problems include risk- taking behavior, psychosomatic disorders (Salama, 2007), nondirected anger, intrusive thoughts, and fear of the future (Omidian, 2001). International aid workers may also be exposed to culture shock and lack of support provided by family or a partner, close friends, and their own culture (Salama). Aid workers who come to know the stories of fear, pain, and suffering of victims may experience similar feelings because they care. This makes them vulnerable to secondary traumatic stress (compassion fatigue) as the emotional residue of exposure to working with victims suffering from the consequences of a traumatic event (ACE-Network, 2007). According to Figley (1995), secondary traumatic stress is “natural consequent behaviors resulting from knowledge about a traumatizing event experienced by a significant other” (Perry, 2003). The symptoms may include avoiding things that are reminders of the event, having difficulty sleeping, or being afraid (Stamm, 2005). Researchers and practitioners have recently acknowledged that professionals who work with or help traumatized people are indirectly or secondarily at risk of developing the same symptoms as

- 14. the individuals who are exposed directly to the trauma (Perry). Perry (2003) advances several reasons that aid workers or professionals working with traumatized victims are at increased risk of developing secondary trauma: (a) empathizing with victims leads aid workers to become vulnerable to internalizing some of the victim’s trauma-related pain; (b) aid workers would have to listen to the same or similar stories over and over again without sufficient recovery time; (c) many aid workers have had some traumatic experiences in their own life and the pain of such experiences can be reactivated when they work with an individual who has suffered a similar trauma; and (d) the current PSYCHOLOGICAL PROBLEMS AMONG AID WORKERS 409 practices in the fields of relief and mental health are based on individual service delivery rather than on team-oriented practice and such practices within a fragmented system (i.e., camps for refugees or internally displaced persons where the turnover is high) are considered to set aid workers up for increased stress. There are some findings suggesting burnout is prevalent among aid workers in complex emergency situations (Cardozo et al., 2005). Burnout is a state of

- 15. physical, mental and emotional exhaustion resulting from prolonged demanding and stressful situations (Pines, Aronson, & Kafry, 1981). According to Stamm (2005, p. 12), burnout is “associated with feelings of hopelessness and difficulties in dealing with work or in doing your job effectively. These negative feelings usually have a gradual onset. They can reflect the feeling that your efforts make no difference, or they can be associated with a very high work load or a non- supportive work environment”. Burnout symptoms can be categorized into five groups, namely, emotional, interpersonal, physical, behavioral, and work-related components (Salama, 2007). The emotional component includes feelings such as depression, anxiety, irritability, and helplessness. The interpersonal category comprises self-distancing, social withdrawal, and inefficient communication. The physical element involves sleep difficulties, fatigue, exhaustion, headaches, and stomachaches. The behavioral aspect includes alcohol abuse, aggression, pessimism, and cruelty. The work-related element includes poor performance, tardiness, and absenteeism. In their study of stress and burnout amongst prehospital emergency teams, Louville, Jehel, Goujon, and Bisserbe (1997) found that women and hospital- based personnel scored significantly higher on depression and distress measured

- 16. by the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ; Goldberg & Williams, 1991), and trait and state anxiety than did men and personnel who intervene in the emergency field. Compassion satisfaction, according to Stamm (2005, p. 12), is about “the pleasure you derive from being able to do your work well. For example, you may feel like it is a pleasure to help others through your work”. Conrad and Kellar-Guenther (2006) studied compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and burnout among Colorado child protection workers using the Compassion Satisfaction/Fatigue Self Test. They found that about 50% of the protection staff experienced high or very high levels of compassion fatigue and low levels of burnout. High compassion satisfaction was associated with reduced fatigue and lower levels of burnout. Most of participants (70%) had high scores for compassion satisfaction. The authors concluded that compassion satisfaction might alleviate the effects of burnout. Cardozo et al. (2005) conducted a study with 285 expatriate aid workers and 325 Kosovar Albanian aid workers from 22 humanitarian organizations carrying out health projects in Kosovo. The study was concerned with mental

- 17. PSYCHOLOGICAL PROBLEMS AMONG AID WORKERS410 health problems related to exposure to traumatic events. Their results showed that younger expatriates reported significantly more depressive symptoms and more nonspecific psychiatric morbidity as measured by the GHQ. Kosovar and expatriate aid workers with a history of psychiatric illnesses also demonstrated higher levels of depressive symptoms and nonspecific psychiatric morbidity. The present study attempted to identify psychological health problems suffered by aid workers assisting victims in Darfur, and aimed to explore the relationship between these problems and burnout and job satisfaction rates among aid workers. Because of the hostile and difficult work environment, as witnessed by the authors inside internally displaced persons camps, it was expected that high rates of burnout and psychological disturbances would be found. method ParticiPants Participants were 53 humanitarian aid workers representing 11 relief organizations operating in camps in Darfur, around the towns of Nyala (40%) and Fasher (60%). The sample was randomly selected from aid workers who

- 18. had firsthand experience with victims inside the camps. The ages of participants ranged between 20 and 55 years (mean age = 31.6 years). Forty- six percent of them were married, 51% single, and 3% were divorced or separated. Sixty percent of the participants were Sudanese nationals while 39.6% were international aid workers. The percentages of male and female participants were 49.0% and 43.4% respectively. Materials and Procedures Participants were requested to complete three questionnaires. The goal of the research and its importance were explained to them. The first questionnaire was the 30-item Professional Quality of Life Questionnaire (ProQOL; Stamm, 2005). It measures compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue (secondary traumatic stress), and burnout. This questionnaire was subjected to factor analysis using equal variances (weights) as prior communality estimates. The factor axis method was used to extract the factors, and this was followed by a varimax (orthogonal) rotation. In our study only the first two factors displayed eigenvalues greater than 1, and the results of a scree test also suggested that only the first two factors were retained for rotation. Combined, factors 1 and 2 accounted for 32.60% of the total variance.

- 19. In interpreting the rotated factor pattern, an item was said to load on a given factor if the factor loading was 0.45 or greater for that factor, and was less than 0.45 for the other. Using these criteria, 17 items were found to load on the first factor, which was subsequently labeled secondary traumatic stress (STS) or PSYCHOLOGICAL PROBLEMS AMONG AID WORKERS 411 compassion fatigue. The average score on the STS scale was 45 (SD = 16.0, alpha reliability = 0.87). Instead of having cutoff scores to indicate relative risks or protective factors, conservative quartile method was used with high (top 25%), middle 50%, and low (bottom 25%). This method has been found to be useful for screening (Stamm, 2005). Six items loaded on the second factor, which was labeled compassion satisfaction (CS). The average score on CS was 23.8 (SD = 5.0, alpha reliability = 0.72). Higher scores on this scale indicate greater satisfaction with one’s ability to be an effective aid worker. The second questionnaire was the 13-item Relief Worker Burnout Questionnaire (Ehrenreich, 2001) which is designed to help detecting burnout among aid workers. A score of 0-15 suggests the aid worker is probably

- 20. coping adequately with the stress of work. A score of 16-25 suggests suffering from work stress and preventive action is recommended. A score of 26-35 suggests possible burnout. A score above 35 indicates probable burnout (Ehrenreich). In our study the average score was 15.0 (SD = 7.5, alpha reliability = .73). The third questionnaire was the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28 items; Goldberg & Williams, 1991). This questionnaire comprises four subscales gauging anxiety, depression, somatic symptoms, and social dysfunction. The GHQ is a well validated instrument for measuring nonpsychotic psychiatric disorders in both clinical and community settings. There are two methods of scoring the GHQ; the first is the GHQ scaling method (0,0,1,1) and the second is the Likert scaling method (0,1,2,3). The former is appropriate for recognizing psychiatric cases and the latter for survey research (Swallow, Lindow, Masson, & Hay, 2003). For differentiating psychiatric from nonpsychiatric cases the GHQ scoring system with a cutoff point of 4 or more is usually used. This system was used in the present study. When using the Likert system, GHQ total score measures general distress. In our study the mean score on this scale was 5.2 (SD = 5.2, alpha reliability = 0.85). results

- 21. Factor analysis was performed on the ProQOL to find out whether or not the factors yielded were consistent with those of Stamm (2005). Unlike Stamm’s study which produced three factors, secondary traumatic stress, burnout, and compassion satisfaction, the present study produced two factors; secondary traumatic stress (STS) and compassion satisfaction (CS). This difference may be attributed to the overlap between secondary traumatic stress and burnout. Stamm (p. 5) stated that “we do not see high scores on burnout with high satisfaction, but there is a particularly distressing combination of burnout with trauma”. About 25% of aid workers in our study scored below 35 on secondary traumatic stress, PSYCHOLOGICAL PROBLEMS AMONG AID WORKERS412 and about 25% of them scored above 60. Concerning compassion satisfaction, the quartile method revealed that 25% of aid workers scored higher than 26 and about 25% of them scored below 21. As for burnout, 63% of participants scored 15 or less, 21% scored 16-25, and 16% scored higher than 25. The GHQ results showed that 50% of the aid workers in our study scored less than 4, while 50% scored higher than 4.

- 22. Correlation analysis showed that burnout was positively related to general distress and secondary traumatic stress and negatively related to compassion satisfaction (see Table 1). Burnout was further positively related to depression, anxiety, somatic symptoms, and social dysfunction (see Table 1). Compassion satisfaction was negatively associated with general distress, anxiety, and social dysfunction (see Table 1). Age was negatively related to burnout and secondary traumatic stress (see Table 1). The older participants experienced less burnout and secondary traumatic stress than did the younger workers. TAble 1 the coefficients of correlation Between different VariaBles Variable Burnout Compassion satisfaction Secondary traumatic stress Depression Somatic symptoms .57** - - - Distress .71** -.33* - - Anxiety .61** -.28* - - Social dysfunction .52** -.28* - Age -.37** - -.46** Burnout - .35** .48** .30* Note: * p < .05; ** p < .01 The t test results indicated significant difference between the two sexes in burnout, (t = 2.901, df = 47, p < 0.01). Female participants scored higher than males. No significant sex differences were found in

- 23. secondary traumatic stress, compassion satisfaction, general distress, and GHQ subscales. There were significant differences between Sudanese and international aid workers in burnout and secondary traumatic stress (t = 2.608, df = 49, p < 0.05; t = 4.389, df = 49, p < 0.001, respectively). Sudanese aid workers suffered more burnout and secondary traumatic stress. Responses on burnout were divided into two groups: scores less than average (15) represents group A, and scores more than 15 represent group B. There were significant differences between the two groups in t test results for anxiety, social dysfunction, somatic symptoms, secondary traumatic stress, and general distress (t = 3.657, df = 50, p < 0.01; t = 2.862, df = 50, p < 0.01; t = 2.654, df = 50, p < 0.05; t = 4.422, df = 51, p < 0.001, t = 3.801, df = 50, p < 0.001, respectively). Those participants with higher than average scores for burnout reported more PSYCHOLOGICAL PROBLEMS AMONG AID WORKERS 413 symptoms of the above mentioned disturbances. Those who were classified as nonpsychotic psychiatric cases, according to the GHQ scoring system, scored higher on burnout than those who were not (t = 4.827, df = 50, p < 0.001).

- 24. No significant differences were found between the two groups in secondary traumatic stress or compassion satisfaction. discussion In the present study, 25% of aid workers scored higher than 60 (the top quartile) on secondary traumatic stress. According to Stamm (2005), if the individual’s score on the secondary traumatic stress scale is in the top quartile, s/he may want to take some time to think about what may be causing distress to him/her at work, or if there is some other reason for the elevated score. While higher scores do not mean that s/he has a problem, they are an indication that s/he may want to examine how s/he feels about his/her work and work environment. The person may wish to discuss this with his/her supervisor, a colleague, or a health care professional (Stamm). In our study the quartile method suggested by Stamm yielded the result that 25% of the participants had high levels of secondary traumatic stress. However, we believe that this percentage could be far lower than the actual incidence of secondary traumatic stress among aid workers. The GHQ results support this claim by showing that 50% of aid workers in Darfur could be classified as nonpsychotic psychiatric cases. This may be due either to the stressfulness of the working environment and the seriousness of the adjustment

- 25. problems encountered by aid workers or to the tendency of maladjusted individuals to choose to become aid workers. This percentage of potential clinical cases (50%) is far higher than the percentages found by Cardozo et al. (2005) in Kosovar Albanian (11.5%) and expatriate aid workers (16.9%). However, it should be noted that the cutoff points used with the GHQ total score were 8 and 9 for the Kosovar Albanian and expatriate aid worker, respectively. These cutoff points are higher than the usual one (4) which was used in the present study. The psychiatric morbidity rate in aid workers in the present study was comparable to Chung, Chung, and Easthope’s (2000) findings in people in a community exposed to traumatic stress related to an aircraft crash (56%), and higher than Chung, Farmer, Werrett, Easthope, and Chung’s (2001) findings that 35% of people exposed to a train disaster scored higher than 4 on the GHQ total score. Concerning compassion satisfaction, 25% of the aid workers scored higher than 26. This suggests that these workers derive a good deal of professional satisfaction from their work. Those (25%) who scored below 21 can be described as very dissatisfied and may either have problems with their job, or there may be other reasons for deriving satisfaction from activities other than their job (Stamm, 2005).

- 26. PSYCHOLOGICAL PROBLEMS AMONG AID WORKERS414 With regard to burnout, it seemed that the majority of the participants (63%) were able to cope, in one way or another, with their work stress and therefore there were low levels of burnout. The remaining 37%, who scored 16 or above on total burnout, could be described as suffering work stress and possible burnout. The latter group might need professional psychological help to assist them with their sufferings. The positive relationship between burnout and secondary traumatic stress is consistent with the findings of Conrad and Kellar-Guenter (2006) who found high levels of compassion satisfaction in individuals with low levels of burnout. This is also consistent with the work of McFarlane (2004) who found that aid workers experienced chronic hassles that could develop into stress and acute traumatic stress. Hence, secondary traumatic stress might be one of the factors through which burnout manifests itself. The positive associations between burnout and general distress and three of the subscales measured by the GHQ (anxiety, somatic symptoms, and social dysfunction) are consistent with the findings of Louville

- 27. et al. (1997) who reported that in women and a hospital-based emergency team burnout was strongly related to depression and distress measured by the GHQ. These results suggest that the burnout process might involve experiencing a variety of psychological disturbances and distress that exceed the aid worker’s ability to cope and thus lead the person to total collapse. Conrad and Kellar-Guenther (2006) found that burnout could result from exposure to prolonged and extreme job stress that consequently leads the aid worker to stop doing the job. If this is the case, controlling for psychological stress can help mitigating burnout. Providing psychological support can help eliminating the feelings of burnout and aid work staff turnover. The higher levels of burnout reported by female participants compared to male participants could be explained by women’s need to prove themselves in more than one capacity: to be wife, mother, woman and employee (see for example, Brunt, 2007). In addition, women, by nature, tend to be more involved in relationships with others, such as pleasing and serving others (Brunt). The negative association between compassion satisfaction (job satisfaction) and burnout supports previous research (i.e., Conrad & Kellar- Guenther, 2006). The negative associations of compassion satisfaction with

- 28. general distress, anxiety, and social dysfunction, support the literature relating job satisfaction to reduced levels of psychological distress. It could be that lack of job satisfaction leads to these feelings or vice versa. The negative associations of age with burnout and secondary traumatic stress suggest that age may moderate the influence of these problems on aid workers. Older aid workers may be more mature and rational in their responses to the demands and associated stress of their job. PSYCHOLOGICAL PROBLEMS AMONG AID WORKERS 415 The high rates of burnout and secondary traumatic stress in Sudanese aid workers compared to the international aid workers might be attributed to the fact that the vast majority of Sudanese aid workers are from Darfur and they themselves are displaced victims of the war. So, their symptoms may be triggered by the combined effect of primary and secondary traumatic stress. Sudanese aid workers are more likely to understand and relate to the tragic stories told by victims who were traumatized because they are familiar with the local dialects. conclusions and imPlications

- 29. This study provides vital information for humanitarian organizations, for aid workers operating in war zones and researchers interested in this field. Aid workers in Darfur encounter several serious adjustment problems. The high incidence of secondary traumatic stress, psychiatric illnesses, and burnout among aid workers can be attributed to experiencing difficult situations such as being in direct contact with highly traumatized victims and a hostile environment. Aid workers tend to be blamed by victims for shortages in services (food, water, shelter, security etc.). This condition may explain the high percentage of aid workers who took little satisfaction from their work. An alternative explanation is that there is a high incidence of people with psychological problems choosing to become aid workers. The implication of this study is that managers and directors of aid organizations should create a positive work climate for their coworkers through equipping aid workers with adequate training, cultural orientation, and psychological support services. It is recommended that an academic discipline specializing in the humanitarian field should be established. This discipline needs to focus on education, training, and research and would help make use of the great source of data that could be scientifically analyzed to reach conclusions which contribute to improving the

- 30. practice of humanitarian assistance in all relevant fields. references ACE-Network. (2007). What is compassion satisfaction? Child trauma web by child trauma academy. Retrieved March 27, 2007, from http://www.ace- network.com/cfspotlight.htm Adams, R. E., Boscarion, J. A., & Figley, C. R. (2006). Compassion fatigue and psychological distress among social workers: A validation study. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76, 103-108. Brunt, G. (2007). An informed view as a means of minimizing the cost to both the individual and the organization as a whole. Retrieved April 9, 2007, from http://www.corporatetraining. co.za/news3.htm Cardozo, B. L., Holtz, T. H., Kaiser, R., Gotway, C. A., Ghitis, F., Toomey, E., & Salama, P. (2005). The mental health of expatriates and Kosovar Albanian humanitarian aid workers. Disasters, 29, 152-170. Chung, M. C., Chung, C., & Easthope, Y. (2000). Traumatic stress and death anxiety among community residents exposed to an aircraft crash. Death Studies, 24, 689-704. PSYCHOLOGICAL PROBLEMS AMONG AID WORKERS416 Chung, M. C., Farmer, S., Werrett, J., Easthope, Y., & Chung,

- 31. C. (2001). Traumatic stress and ways of coping of community residents exposed to a train disaster. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 35, 528-534. Conrad, D., & Kellar-Guenther, Y. (2006). Compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction among Colorado child protection workers. Child Abuse & Neglect, 30, 1071-1080. Ehrenreich, J. H. (2001). Coping with disasters: A guidebook to psychosocial intervention. (Revised ed.). Toolkit web by NGOs, sports club, and governments. Retrieved March 18, 2005, from http://www.toolkitsportdevelopment.org/stml/topic Figley, C. R. (1995). Compassion fatigue as secondary traumatic stress disorder: An overview. In C. R. Figley (Ed.), Compassion fatigue (pp. 1-20). New York: Brunner Mazel. Goldberg, D., & Williams, P. (1991). A user’s guide to the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ). Hampshire: The Basingstoke Press Ltd. Louville, P., Jehel, L., Goujon, E., & Bisserbe, J. C. (1997). European Psychiatry, 12, suppl. 2, 186s. McFarlane, C. A. (2004). Risks associated with the psychological adjustment of humanitarian aid workers. The Australian Journal of Disaster, 1. Retrieved April 20, 2007, from http://www. massey.ac.nz/~trauma/ Omidian, P. (2001). Aid workers in Afghanistan: Health

- 32. consequences. The Lancet, 358, 1545. Perry, B. D. (2003). The cost of caring: Secondary traumatic stress and the impact of working with high-risk children and families. Child trauma web by child trauma academy. Retrieved March 13, 2007, from http://www.childtraumaacademy.org Pines, A., Aronson, E., & Kafry, D. (1981). Burnout: From tedium to personal growth. New York: Free Press. Salama, P. (2007). The psychological health of relief workers: Some practical suggestions. Relief web by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Retrieved March 7, 2007, from http://www.reliefweb.int/library/documents/psycho.htm Stamm, B. H. (2005). The ProQOL Manual: The Professional Quality of Life Scale: Compassion Satisfaction, Burnout & Compassion Fatigue/Secondary Traumatic Scale. Baltimore: Sidran Press. Swallow, B. L., Lindow, S. W., Masson, E. A., & Hay, D. M. (2003). The use of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28) to estimate prevalence of psychiatric disorders in early pregnancy. Psychology, Health, & Medicine, 8, 213-217. UNDP. (2004). Human Development Reports. Human development reports web by the United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved October 17, 2005, from http://hdr.undp.org/ reports/global/2004/

- 33. Wikipedia. (2007). Darfur Conflict. Retrieved February 22, 2007, from http://en.wikipedia.org/ wiki/Darfur_conflict The Effects of Vicarious Exposure to the Recent Massacre at Virginia Tech Carolyn R. Fallahi and Sally A. Lesik Central Connecticut State University The authors examined whether exposure to the April 2007 Virginia Tech school shootings would increase symptoms of acute stress in students at another university who were not personally involved, but who followed the case vicariously through news media. The authors ran a series of regression analyses using multinomial logit (MNL) models, a methodology which can be used for dealing with categorical outcome variables. The authors found that as TV viewing of the Virginia Tech case increased, the probability that a student would respond with moderate or acute stress symptoms also increased. The authors were able to describe the magnitude of the relationship between vicarious exposure to the Virginia Tech case and acute stress symptomatology. Keywords: Virginia Tech tragedy, vicarious exposure,

- 34. multinomial logit models, acute stress disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder On April 16, 2007, Cho Seung-Hui, a 23-year- old student, murdered 32 people and wounded 25 others before committing suicide at Virginia Poly- technic Institute (Virginia Tech) in Blacksburg, Virginia. It was the deadliest campus shooting in the history of the United States. The media cov- erage of this incident was extensive with daily images of the shooter and victims available on news stations throughout the country for weeks following the incident. We wondered about the effects on students at another university who were not personally involved with the Virginia Tech shootings, but who followed the case vicariously through news media. Responses to Other Tragedies The destruction of the World Trade Center is probably the most “imaged disaster in human history” (Mason, 2004, p. 1). Symptoms were not contained to New York, people living throughout the United States experienced symp- toms of stress as a direct result of 9/11 (Schuster et al., 2001; Stein et al., 2004). A study of children who experienced indirect exposure to 9/11 through the media showed increased levels of worry and posttraumatic stress at levels com- parable to those in children experiencing the disasters directly (Lengua, Long, Smith, & Meltzoff, 2005). This research confirms Pfeffer- baum, Gurwitch, et al. (2000) and Pfefferbaum, Seale, et al. (2000) who found that children

- 35. experienced symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) 2 years after the Oklahoma City bombing if they lived within 100 miles of the bombing and had a connection to someone who either died or was hurt in the bombing. Spang (1999) found few symptoms of distress among adults living 900 miles away from Okla- homa City as compared to the Oklahoma City residents 6 months after the Oklahoma City bombing. Stein et al. (2004) found that 2–3 months following the 9/11 terrorist attacks, many adults continued to show stress-related symptoms as a direct result of the attacks. Fol- lowing the explosion of the Shuttle Challenger in 1986, Terr, Block, Michel, Shi, Reinhardt, and Metayer (1999) studied the responses of children living in the east and west coast both 5–7 weeks and 14 months after the explosion. They found that children who watched the Chal- lenger explode and cared more about the teacher on the Challenger, demonstrated more symp- toms of PTSD initially. Carolyn R. Fallahi and Sally A. Lesik, Department of Psychology and Department of Mathematical Sciences, Central Connecticut State University. We thank Lisa Leishman, Melissa Cotter, and Sara R. Fallahi, who coded much of the data for this study; Sally K. Laden, who provided editorial assistance; and Dr. Bradley Waite for his comments on earlier drafts of this article. Correspondence concerning this article should be ad- dressed to Carolyn R. Fallahi, Central Connecticut State University, Department of Psychology, 208 Marcus White Hall, 1615 Stanley Street, New Britain, CT 06050-4010.

- 36. E-mail: [email protected] Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy © 2009 American Psychological Association 2009, Vol. 1, No. 3, 220 –230 1942-9681/09/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/a0015052 220 On April 20, 1999, Littleton, Colorado expe- rienced the deadliest act of school violence re- corded in history prior to the Virginia Tech case. Two students killed 12 students and one teacher while wounding 21 others before com- mitting suicide. The images of this tragedy were aired continuously (Addington, 2003). Colum- bine students throughout the country reported fear of victimization at school (Brooks, Schiraldi, & Ziedenberg, 2000). Addington (2003) found students responded to Columbine with an increase in fear at school, albeit a small increase. This brings up an important question: does exposure to a disaster vicariously increase psychiatric symptomatology in samples of peo- ple not directly exposed to the tragedy? Media Violence Research During the last half century, the negative short-term and long-term effects of media vio- lence have been well documented. Exposure to media violence has been associated with the formation of aggressive scripts in memory, hos- tile attributional biases, and aggressive beliefs (Huesmann, Moise-Titus, Podolski, & Eron,

- 37. 2003). There is also a link between a heavy diet of media violence and later aggression (Bush- man & Anderson, 2001; Paik & Comstock, 1994). Further, the effects of media violence include the augmentation of negative mood states (Caprara, Renzi, Amolini, D’Imperio & Travaglia, 1984), including aggressive emo- tions (Anderson et al., 2003). Viewing indirect aggression on TV early in life has been shown to predict actual indirect aggression in real life (Huesmann et al., 2003; Coyne & Archer, 2005). Vicarious exposure in terms of the number of hours of media viewing of 9/11 was studied by Blanchard et al. (2004). They found that vicar- ious exposure, as measured by the number of hours of media viewing of 9/11 events, pre- dicted acute stress disorder scores in two sam- ples of college students who were not geograph- ically positioned near New York City. Pfeffer- baum, Gurwitch, et al. (2000) also found that media exposure and indirect interpersonal ex- posure, as defined by having a friend who knew someone hurt or killed in the bombing, were significant predictors of symptomatology. Gil- Rivas, Holman, and Silver (2004) found that adolescents who were indirectly exposed through media coverage to the events of 9/11 experienced mild to moderate acute stress symptoms, especially when there was signifi- cant conflict with their parents. Propper, Stick- gold, Keeley, and Christman (2007) found that there was a strong relationship between media exposure for 9/11 and changes in dream features

- 38. following the attack. Specifically, they found that with every hour of TV viewing, this re- sulted in a 5% to 6% increase in September 11th dream references. Talking about the events with friends and relatives was not significantly re- lated to specific dream references. The authors concluded that the media may have a “deterious impact on the emotional well-being of U.S. citizens in the aftermath of September 11” (p. 340). Pfefferbaum, Gurwitch, et al. (2000) found that following the Oklahoma City bomb- ing, children who lost a friend reported signif- icantly more symptoms of PTSD than those who lost an acquaintance. However, when look- ing at children within the community, there was not a significant difference between those per- sonally involved in the bombing, for example, knew someone that was hurt or killed, and those children not personally involved. The authors speculate that this may be due to the fact that children were watching only bomb-related pro- gramming that aired for months after the explo- sion. They speculated that high levels of media coverage contributed to the symptoms of the children within the community. Rosen, Quyen, Cavella, Finney, and Lee (2005) found that exposure to 9/11 images did not change the average symptoms of distress in a group of chronic PTSD patients. However, they reported an increase in their perceptions of stress and the authors speculate that the 9/11 events may have caused the patients to misat- tribute fluctuations in chronic symptoms to the recent terrorist attacks.

- 39. The News Media News coverage can be a vehicle through which individuals can experience indirect vic- timization (Warr, 1994). The news media can play an important role in defining ‘what is a public tragedy’ (Balk, 2004). The news media can present a distorted image of the risks that individuals face in response to tragedies like Columbine’s school shootings (Brooks, Schiraldi, & Zeidenberg, 2000). Public trage- 221EFFECTS OF VICARIOUS EXPOSURE TO VIRGINIA TECH dies affect our views on life and shatter our basic assumptions about life (Balk, 2004). Chiricos, Padgett, and Gertz (2006), as well as Chiricos, Eschholz, and Gertz (2000) found a relationship between watching TV news cover- age of traumatic events and an increase in fear. We were interested in studying the subjective reactions of students at a large state university in the northeast following the shooting at Vir- ginia Tech. We hypothesized that there would be a significant relationship between vicarious exposure through the news media to the Vir- ginia Tech case and acute stress symptoms. Method Student Participants

- 40. We recruited 145 female and 167 male par- ticipants from undergraduate and graduate psy- chology courses. Students who were enrolled in the introductory psychology and life span de- velopment courses fulfilled course research re- quirements by participating in psychology stud- ies. Students signed up for any of a number of different studies, and all received extra credit for participating. Demographics The participants primarily consisted of fresh- man, sophomores, and juniors (96.4%), with a mean age of 19.56 years (SD � 3.72), and a median grade point average of 3.00, who iden- tified themselves as single (96.7%). This was a primarily Caucasian sample (82.1%), with 9.2% self-identifying as African American/ Black, 5.1% as Hispanic or Latino, 1.5% as Asian, and 0.9% as Other. Survey Participants were asked to estimate the num- ber of hours spent viewing news coverage of the shootings at Virginia Tech that included both TV and internet viewing of this case. They participated approximately 3 weeks after the incident occurred and provided an estimate of hours spent viewing news coverage since the event. In addition, they were asked to rate their own symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress-related symptoms, (scale of 1 [not at all] to 5 [very much so]). Symptoms were converted

- 41. to a categorical scale by rating 1 (no symptoms), 2–3 (moderate symptoms), and 4 –5 (acute symptoms). This conversion was done for two reasons. First, by combining outcome catego- ries, we were able to obtain more efficient esti- mates by combining indistinguishable catego- ries. Second, these conversions aligned with the severity of the given symptom. The survey measures included self-ratings of the following symptoms of acute stress disorder as taken from the symptom list presented in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000): (1) Intrusive Thoughts: Experiencing thoughts associated with the Virginia Tech case. (2) Sleep Disturbance: Experiencing sleep disturbance, for example, trouble falling asleep, trouble staying awake at night, sleeping longer than usual. (3) Appetite Disturbance: Experiencing ei- ther an increase or decrease in appetite. (4) Nightmares: Experiencing nightmares about the Virginia Tech case. (5) Fear: Increasing feelings of fear that something like the Virginia Tech case could either happen again somewhere else or at this university. (6) Stomach Upset: Experiencing gastroin-

- 42. testinal distress, for example, upset stomach, butterflies in your stomach, and so forth (7) Depressive Symptoms: Experiencing a sad or down mood. (8) Symptoms of Suicide: Experiencing an increase in suicidal ideation as a direct result of the Virginia Tech case. (9) Disorganization: Feeling disorganized, confused, and “in a daze.” (10) Alcohol and Drugs: An increase in al- cohol or drug use. (11) Replaying the Event: Reliving the trauma of the Virginia Tech Case Invol- untarily. 222 FALLAHI AND LESIK (12) Anger: Experiencing symptoms of an- ger as a direct result of the Virgina Tech case. (13) Guilt: Experiencing symptoms of guilt as a direct result of the Virginia Tech case. Predictor Variables The predictor FEMALE represents the respon-

- 43. dents’ self-identified gender (FEMALE � 1 for female respondents, and FEMALE � 0 for males). The predictor AGE Is the respondent’s age in years. A respondent’s self-identified race/ethnicity was coded as the dummy predictor MINORITY (MINORITY � 1 if the respondent self- identified as nonwhite; and MINORITY � 0 when the respondent self-identified as white). The predictor HOURS represents the number of hours of TV coverage of the VT shootings. Response Variables There were 14 response variables that repre- sented different symptoms. The self-reported severity for each of the symptoms was initially represented on a 5-point Likert scale and were combined as a categorical variable on a scale of no symptoms, moderate symptomatology, and acute symptomatology. The 14 symptoms stud- ied represented symptoms of acute stress disor- der and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) based on the DSM–IV–TR manual (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Table 1 gives the distribution of the three combined catego- ries based on each of the 14 symptoms. Statistical Analysis We ran a series of regression analyses us- ing the multinomial logit (MNL) model. We chose the MNL because it is the preferred

- 44. method for regression models in which the response variable has more than two catego- ries. Even though the initial Likert scale was ordinal, we chose the MNL because it does not rely on the parallel regression assumption (Long & Freese, 2003). The categories were collapsed to represent experiencing none, moderate, or acute symptoms. The initial ba- sic MNL model equation used for each symp- tom is presented in Equation 1. mlogit(Symptom) � �0 � �1FEMALE � �2AGE � �3MINORITY � �4HOURS � ε. (1) More formally, the MNL fodel can be written as a series of binary logits as in Equation 2. ln(Symptom�m)/b�X � ln P(Symptom � m�X P(Symptom � b�X � ��m�/bX � �0 �m�/b � �1 �m�/bFEMALE � �2 �m�/bAGE � �3 �m�/bMINORITY � �4

- 45. �m�/bHOURS. (2) Parameter b represents the base category, and m ranges from 1 to J, where J represents the number of categorical outcomes, and X de- scribes the vector of control variables. For this study, J � 3 because there are three distinct outcome categories representing the three cate- gories of symptomatology. Since there can be more than one solution for the estimated coefficients in a MNL analysis, one of the coefficients needs to be set to 0 in order to identify the model. This is category is referred to as the base category, and it does not Table 1 Distribution of Student Response to the Different Symptoms Symptom None Moderate Acute Missing Intrusive thoughts 204 95 12 28 Sleeping 263 40 10 26 Appetite 277 33 3 26 Distraction 241 59 13 26 Nightmares 270 38 5 26 Fear 200 88 25 26 Butterflies in stomach 268 35 10 26 Depression 261 38 14 26 Suicide 305 5 3 26 Disorganization 261 43 8 27 Alcohol/drugs 278 28 5 28 Replaying the event 262 42 7 28 Anger 245 55 11 28 Guilt 274 30 7 28

- 46. 223EFFECTS OF VICARIOUS EXPOSURE TO VIRGINIA TECH matter which category is chosen because the predicted probabilities will be the same regard- less of which parameterization (or base cate- gory) is used (Long, 1997). For our study, we set the base category to None, thus the MNL model would fit model Equations 3 and 4 for each of the 14 symptoms. ln(Symptom � ModerateNone) � �iX �Moderate)/None (3) ln(Symptom � AcuteNone) � �iX �Acute)/None (4) Where �iX ���/None is the ith coefficient for category k using the category None as the base category. The remaining coefficients are then estimated with respect to this base category. Tests for Dependent Categories We used a Wald test to determine whether the outcome categories could be combined for the 14 regression models (Long & Freese, 2003). The advantage to combining outcome categories is to combine categories which are

- 47. indistinguishable in order to obtain more effi- cient estimates (Long & Freese, 2003). The null hypothesis for such a test is that two categories can be combined (Long, 1997), and thus there is no difference in the separate odds ratios for the combined categories. For all of the 14 regres- sion models, we found that categories 2 and 3 could be collapsed into a single category ( p � .10). We are calling this combined category Moderate since this category represents a mod- erate reaction to the given symptom. We also found that categories 4 and 5 could be collapsed ( p � .30), and called this category Acute since it represents a severe reaction to the given symptom. By keeping the 5-point scale, the pairwise comparisons between different catego- ries would be numerous and difficult to under- stand, while not giving us any new information. Further, the Wald test showed that there was not a significant difference between these two cat- egories and combining them made conceptual sense. Testing the Effects of Independent Variables Since there are J � 3 outcome categories, then there are J – 1 � 2 coefficients associated with each independent variable. By using cate- gory None as the base category, there are two coefficients that would be associated with each predictor namely �i �Moderate)/None, and �i �Acute)/None.

- 48. The null hypothesis that predictor i does not affect the outcome can be written as: H0:�i (Moderate)/None � �i (Acute)/None � 0 Table 2 shows the individual parameter esti- mates and standard errors for all 14 regression analyses. Table 3 gives the results using a like- lihood ratio test that was used to determine which groups of predictors are significant for each of the 14 regression analyses (Long, 1997; Long & Freese, 2003). Similar to Mickey and Greenland’s (1989) criteria for including variables in a logistic re- gression analysis, we used p values that are less than 0.10 as the initial criteria for testing the effects of the independent variables. Using more traditional significance levels such as p � .05 may fail to identify variables that are sig- nificant for some of the categories but not for others. Perfect Predictions The MNL model cannot be used if there are perfect predictors. In other words, if there is no variability in a predictor variable within one of the outcome categories, this produces excessively large standard errors and unstable parameter estimates. Perfect predictors can occur if there are only a few observations in a given outcome category and if one or more of

- 49. the predictor variables does not vary within this outcome category. This scenario can be seen in the Acute category for the predictor variable MINORITY for the symptoms of Ap- petite, Nightmares, Alcohol and Drugs, Re- playing the Event, and Guilt, and for the pre- dictor variable FEMALE for the category of Suicide as is presented in Table 2. By remov- ing these predictor variables and running the regression analysis along with performing the appropriate likelihood ratio test, the effect of 224 FALLAHI AND LESIK these variables on the other outcome catego- ries gave results similar to those presented in Table 3. The IIA Assumption The MNL relies on the assumption known as the independence of irrelevant alternatives (IIA). Essentially, the IIA assumption stipulates that adding or deleting outcome categories will not affect the odds ratio of the remaining out- comes (Green, 2003; Maddala, 1983). We ran the Hausman test (Hausmann & McFadden, 1984) for all 14 regression analyses with the three combined categories and there was no evidence to suggest that the IIA assumption has been violated ( p � .80). Interpretation of the Results

- 50. Although the MNL can be considered as a simple extension of the logistic regression Table 2 Estimated MNL Coefficients and Standard Errors [in Brackets] for the MNL Model Comparing All Possible Combinations for Each of the Three Response Categories (N � 339) Symptom Categories FEMALE AGE MINORITY HOURS CONS Intrusive thoughts None Moderate 0.171 [0.268] �0.085 [0.059] 0.420 [0.374] 0.024 [0.025] 0.691 [1.171] None Acute �0.386 [0.670] �0.080 [0.162] �0.405 [1.054] 0.108�� [0.035] �1.630 [3.214] Moderate Acute �0.558 [0.685] 0.005 [0.167] �0.825 [1.064] 0.084� [0.035] �2.322 [3.319] Sleeping None Moderate 0.225 [0.357] �0.156 [0.104] �0.037 [0.540] 0.035 [0.029] 0.988 [2.032] None Acute 0.117 [0.766] �0.035 [0.154] 0.642 [0.919] 0.097�� [0.035] �3.500 [3.110] Moderate Acute �0.109 [0.818] 0.121 [0.182] 0.679 [1.021] 0.062 [0.039] �4.487 [3.635] Appetite None Moderate �0.255 [0.400] �0.037 [0.078] �0.041 [0.581] 0.031 [0.032] �1.400 [1.556] None Acute �0.078 [2.363] �0.178 [0.707] 21.815 [13.870] 0.143� [0.067] �23.533 [N/A] Moderate Acute 0.176 [2.383] �0.141 [0.710] 21.856 [13.939] 0.111 [0.070] �22.133 [N/A] Distraction None Moderate 0.271 [0.317] �0.090 [0.075] 0.090

- 51. [0.464] 0.007 [0.030] 0.170 [1.482] None Acute �0.046 [0.604] 0.004 [0.084] 0.532 [0.738] 0.084�� [0.031] �3.454� [1.744] Moderate Acute �0.318 [0.652] 0.094 [0.110] 0.442 [0.821] 0.077� [0.038] �3.624 [2.224] Nightmares None Moderate 0.656† [0.375] �0.242� [0.124] �0.161 [0.577] 0.042 [0.026] 2.322 [2.385] None Acute 0.651 [0.933] �0.469 [0.434] �35.479 [N/A] 0.073 [0.071] 4.691 [8.205] Moderate Acute �0.005 [0.983] �0.227 [0.447] �34.319 [N/A] 0.031 [0.074] 2.369 [8.455] Fear None Moderate 1.200�� [0.291] �0.060 [0.049] �0.655 [0.477] 0.051† [0.028] �0.377 [0.995] None Acute 1.838�� [0.582] �0.145 [0.138] �0.037 [0.717] 0.114�� [0.034] �0.988 [2.719] Moderate Acute 0.639 [0.604] �0.085 [0.140] 0.618 [0.768] 0.063† [0.032] �0.610 [2.776] Butterflies in stomach None Moderate 0.286 [0.391] �0.085 [0.095] 0.181 [0.550] 0.045 [0.031] �0.735 [1.884] None Acute �0.152 [0.739] 0.020 [0.094] 0.403 [0.915] 0.111�� [0.035] �4.413� [1.975] Moderate Acute �0.438 [0.807] 0.105 [0.131] 0.221 [1.020] 0.066† [0.039] �3.677 [2.678] Depression None Moderate 0.070 [0.366] �0.169 [0.110] �0.604 [0.652] 0.021 [0.032] 1.399 [2.143] None Acute �0.418 [0.604] 0.018 [0.075] 0.107 [0.785] 0.073� [0.031] �3.474� [1.560] Moderate Acute �0.487 [0.680] 0.187 [0.131] 0.710 [0.979] 0.052 [0.403] �4.873† [2.606]

- 52. Suicide None Moderate �0.913 [1.189] �0.411 [0.447] 2.104� [1.050] �0.022 [0.097] 3.546 [8.445] None Acute �43.266 [N/A] 0.035 [0.385] 2.300† [1.380] 0.108† [0.058] �6.139 [7.894] Moderate Acute �36.354 [N/A] 0.447 [0.584] 0.196 [1.709] 0.129 [0.109] �9.685 [11.479] Disorganization None Moderate 0.051 [0.360] �0.084 [0.089] �0.341 [0.575] 0.061� [0.025] �0.428 [1.753] None Acute �0.973 [0.886] 0.062 [0.071] 0.760 [0.899] 0.051 [0.044] �4.780�� [1.564] Moderate Acute �1.024 [0.934] 0.146 [0.112] 1.101 [1.028] �0.011 [0.045] �4.367† [2.317] Alcohol/drugs None Moderate �0.560 [0.433] �0.038 [0.084] �0.399 [0.666] 0.026 [0.030] �1.303 [1.689] None Acute 1.179 [1.166] �0.255 [0.365] �31.707 [N/A] �0.061 [0.171] 0.468 [6.998] Moderate Acute 1.739 [1.229] �0.217 [0.373] �31.308 [N/A] �0.087 [0.173] 1.770 [7.167] Replaying None Moderate 0.119 [0.363] �0.063 [0.078] �1.852� [0.900] 0.074�� [0.027] �0.798 [1.569] None Acute 0.859 [0.883] �0.203 [0.276] �32.704 [N/A] 0.070 [0.074] �0.270 [5.364] Moderate Acute 0.741 [0.930] �0.139 [0.284] �35.858 [N/A] �0.004 [0.076] 0.527 [5.525] Anger None Moderate �0.208 [0.332] 0.006 [0.047] 0.173 [0.456] 0.090�� [0.028] �1.956 [0.962] None Acute 0.281 [0.713] 0.019 [0.086] �0.137 [1.027] 0.130�� [0.040] �4.411� [1.825] Moderate Acute 0.489 [0.747] 0.013 [0.093] �0.310 [1.059] 0.040 [0.036] �2.456 [1.977] Guilt None Moderate �0.234 [0.437] �0.130 [0.123] 0.394

- 53. [0.568] 0.027 [0.029] 0.174 [2.405] None Acute 0.233 [0.856] �0.086 [0.219] �35.771 [N/A] 0.117� [0.053] �2.570 [4.378] Moderate Acute 0.467 [0.942] 0.045 [0.248] �40.166 [N/A] 0.090 [0.058] �2.745 [4.932] † p � .10. � p � .05. �� p � .01. 225EFFECTS OF VICARIOUS EXPOSURE TO VIRGINIA TECH model, the interpretations are much more diffi- cult to describe because of the large number of comparisons that are involved. Furthermore, by combining some of the outcome categories, this provides analyses that are more efficient (Long & Freese, 2003). Predicted probabilities can be used as a way to quickly and succinctly sum- marize the probability of a given outcome cat- egory given a specific set of values of the pre- dictor variables (Long & Freese, 2003). For the MNL, this corresponds to estimating the prob- ability that is described in Equation 5. P̂ �Symptom � m�X� � exp�X�̂�m�/J� � i � 1 J exp�X�̂�i�/J�

- 54. (5) Where m is the desired outcome category, J is the number of categories and X is the vector of covariates. Figure 1 presents the graphs of the predicted probabilities for all of the regression models that tested out as significant ( p � .10). For example, as TV viewing increases, so too does the probability that a participant will self-rate as experiencing fear. Specifically, after viewing 10 hours of TV coverage of Virginia Tech, partic- ipants had a 9.4% chance of experiencing acute symptoms of fear. After 25 hours of coverage, this percentage jumped to 30.7%. As expected, after viewing only 5 hours of news coverage, participants had a 66.2% chance of reporting no symptoms. But as their viewing hours increased to 25 hours of news coverage, the percentage decreased to a 34.1% chance of reporting no symptoms. Odds Ratios In order to describe the relationships among the outcome categories, odds ratios (or factor change coefficients) can be used (Long, 1997; Long & Freese, 2003). To describe the factor change in the odds of outcome m versus out- come n as the predictor variable HOURS in- creases by is described by equation (6). m/n�x,HOURS � �

- 55. m/n�x,HOURS� � e�HOURS, m/n (6) Table 4 provides the odds comparing each of the outcome categories. To interpret the odds ratio, for a standard deviation increase in the amount of hours watched of the VT shootings, the odds of experiencing an acute intrusive thought are 1.8076 times greater as compared to experiencing nothing (holding all other factors fixed). The range of the odds for experiencing an acute symptom as compared to experiencing no symptoms what-so-ever ranged from 1.4769 for Guilt to 3.1983 for symptoms of Appetite. Discussion We assessed college students’ responses to the shooting at Virginia Tech in the first few weeks after the event occurred. The value of using MNL allowed us to develop a predictive model that describes more than simple correla- tional relationships. This technique is a pre- ferred method for looking at categorical depen- dent variables, and allows us to make compar- isons between categories resulting with an odds ratio that allows us to describe the magnitude of the differences in self-reported measures of stress between the categories based on the num- ber of hours watched. In addition, this modeling strategy allows the researcher to include any

- 56. covariates that might be deemed important. In this study, we were able to show that as TV viewing of the Virginia Tech case in- Table 3 Chi-Squared Statistics and p-Values for Testing the Effects of Each of the Independent Variables for Each of the Fourteen Symptoms (df � 2) Symptom Variable FEMALE AGE MINORITY HOURS Intrusive thoughts 0.878 3.022 1.565 9.024� Sleeping 0.408 3.240 0.465 7.831� Appetite 0.410 0.339 1.860 7.974� Distraction 0.763 2.048 0.495 7.190� Nightmares 3.482 7.474� 1.826 3.052 Fear 25.285�� 3.163 2.145 13.183�� Stomach 0.608 1.171 0.264 10.809�� Depression 0.553 3.500 1.022 5.019† Suicide 5.459† 1.264 6.066� 4.709† Disorganization 1.400 1.838 1.098 6.103� Alcohol/drugs 3.043 1.031 1.304 0.815

- 57. Replaying the event 1.073 1.652 8.557� 7.203� Anger 0.627 0.056 0.178 17.396�� Guilt 0.378 1.728 4.247 4.373 Note. † p � .10. � p � .05. �� p � .01. 226 FALLAHI AND LESIK creased, so too does the probability that a par- ticipant will self-rate as experiencing acute symptoms of intrusive thoughts, sleep distur- bance, distraction, fear, stomach upset, depres- sion, disorganization, replaying of the event, and symptoms of anger. The probability of ex- periencing acute symptoms for intrusive thoughts, sleep and appetite disturbance, dis- 0 .2 .4 .6 .8 P re d ic

- 58. te d P ro b a b ili ty 0 10 20 30 40 50 Hours None Moderate Acute Fear Fear None Moderate Acute Hours 0.6621 0.2792 0.0587 5 0.5932 0.3129 0.0939 10 0.5148 0.3398 0.1453 15 0.4293 0.3545 0.2162 20 0.3411 0.3525 0.3065 25 0.2567 0.3319 0.4114 30 0.1826 0.2954 0.5221 35 0.1231 0.2491 0.6278 40 0.0791 0.2005 0.7204 45 0.0490 0.1553 0.7957 50 0

- 59. .2 .4 .6 .8 P re d ic te d P ro b a b ili ty 0 10 20 30 40 50 Hours None Moderate Acute Stomach Stomach None Moderate Acute Hours

- 60. 0.8637 0.112 0.0243 5 0.8261 0.1325 0.0414 10 0.7767 0.1540 0.0693 15 0.7122 0.1746 0.1131 20 0.6305 0.1911 0.1783 25 0.5324 0.1995 0.2681 30 0.4237 0.1963 0.3800 35 0.3154 0.1807 0.5038 40 0.2197 0.1556 0.6247 45 0.1441 0.1262 0.7297 50 0 .2 .4 .6 .8 P re d ic te d P ro b a b

- 61. ili ty 0 10 20 30 40 50 Hours None Moderate Acute Anger Anger None Moderate Acute Hours 0.7891 0.1832 0.0277 5 0.6877 0.2650 0.0473 10 0.5635 0.3605 0.0760 15 0.4298 0.4564 0.1137 20 0.3048 0.5372 0.1581 25 0.2023 0.5919 0.2058 30 0.1274 0.6185 0.2541 35 0.0771 0.6213 0.3016 40 0.0453 0.6067 0.3479 45 0.0261 0.5805 0.3933 50 Figure 1. Predicted probabilities for all significant regression models based on number of hours of viewing the VT shooting at the p � .01 level. 227EFFECTS OF VICARIOUS EXPOSURE TO VIRGINIA TECH traction, fear, stomach disturbance, and anger were less than 9% for TV viewing of 10 hours

- 62. and from 30% to 62% for 40 hours of exposure to the Virginia Tech case. For suicide, disorga- nization, and replaying, the probability of expe- riencing acute symptoms was less than 3% for 10 hours of TV exposure and from 3.55 to 10.73% for 40 hours of exposure. Further, we were able to show that for each hour watched of the Virginia Tech shootings, the odds of expe- riencing acute symptoms increased from 1.48 to 3.20 times, depending on the symptom. This study improves over past research in allowing us to predict the probability of experiencing acute symptomatology as the result of exposure to real life violence in the media by going beyond showing a relationship and actually quantifying the magnitude of that relationship. Table 4 Factor Change in the Odds of Symptoms Based on Number of Hours Watched Symptom Outcome comparison Parameter estimate (b) Factor change in the odds Intrusive thoughts Acute-None 0.10440 1.8076�� Acute-Moderate 0.07536 1.5331� Moderate-None 0.02904 1.1790 Sleeping Acute-None 0.10172 1.8017�� Acute-Moderate 0.06801 1.4824† Moderate-None 0.03370 1.2154 Appetite Acute-None 0.20086 3.1983��

- 63. Acute-Moderate 0.17387 2.7357� Moderate-None 0.02699 1.1691 Distraction Acute-None 0.09621 1.7452�� Acute-Moderate 0.07560 1.5489� Moderate-None 0.02062 1.1267 Nightmares Acute-None 0.03491 1.2261 Acute-Moderate �0.00487 0.9720 Moderate-None 0.03978 1.2615† Fear Acute-None 0.11578 1.9692�� Acute-Moderate 0.07095 1.5148� Moderate-None 0.04482 1.3000 Butterflies in stomach Acute-None 0.11541 1.9503�� Acute-Moderate 0.07297 1.5255� Moderate-None 0.04244 1.2785 Depression Acute-None 0.07515 1.5449�� Acute-Moderate 0.06220 1.4334† Moderate-None 0.01295 1.0778 Suicide Acute-None 0.10801 1.8886† Acute-Moderate 0.12714 2.1136 Moderate-None �0.01913 0.8935 Disorganization Acute-None 0.05780 1.3979 Acute-Moderate 0.00545 1.0321

- 64. Moderate-None 0.05235 1.3544� Alcohol/drugs Acute-None �0.06305 0.6936 Acute-Moderate �0.08400 0.6142 Moderate-None 0.02095 1.1293 Replaying the event Acute-None 0.02901 1.1833 Acute-Moderate �0.01686 0.9068 Moderate-None 0.04586 1.3049� Anger Acute-None 0.13470 2.1848�� Acute-Moderate 0.03335 1.2135 Moderate-None 0.10135 1.8004 Guilt Acute-None 0.06720 1.4769† Acute-Moderate 0.02519 1.1574 Moderate-None 0.04201 1.2760 † p � .10. � p � .05. �� p � .01. 228 FALLAHI AND LESIK As psychologists working in prevention, it is helpful to know how many hours of TV viewing are associated with the development of symp- tomatology. Further, it is now apparent that clinicians working with clients following a trau- matic event need to incorporate questions about vicarious exposure to the event in their assess- ments. Psychologists and Educators need to be better informed about how to help students cope with viewing high-profile media events. Finally,

- 65. this research gives more evidence that Psychol- ogists should work harder to advise newscasters on the potential negative responses to violent media. Research exploring gender differences in fear reactions to mass media has consistently shown that females respond with greater frequency and magnitude to audiovisual images in studies pro- duced from 1987 to 1996 and more recently (Peck, 1999; Valkenburg, Cantor, & Peeters, 2007). Similar results were found in the exam- ination of females responses to the Virginia Tech case as females experienced significantly more symptoms of fear via their self-ratings as compared to males. No gender differences were seen in the other 13 acute stress symptomatol- ogy. This makes more of a case for the detri- mental effects of vicarious exposure to TV. The effects seem to be due to TV watching as op- posed to differences between the male and fe- male participants in our study. Additionally, past research has shown that age and race are factors that make one vulner- able to the effects of violent media exposure (Tucker et al., 2000; Pulcino et al., 2003). In this sample, we did not have a large distribution of participants from varying age or minority status. Our sample was too biased in that par- ticipants were primarily in late adolescence or emerging adulthood and were primarily Cauca- sian. Future research will need to document the probabilities of experiencing increased preva- lence and magnitude of symptomatology based on vicarious exposure to violent media for other

- 66. samples. The generalizability of this study is limited because of the lack of standard measures and the reliance on self-report of the participants. In addition, exposure, as measured by the number of hours watching news reports about this inci- dent, was based on self-report without objective corroboration. Finally, without a pretest mea- sure of symptoms of PTSD, we are limited in drawing a causal inference that the media ex- posure was the cause of the acute stress symp- toms in our sample. Other factors such as stress surrounding upcoming examinations or other stressful events in the life of a student may in fact have influenced their self-reported mea- sures of stress. References Addington, L. A. (2003). Students’ fear after Colum- bine: Findings from a randomized experiment. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 19, 367–387. American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnos- tic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text revision). Washington, DC: Author. Anderson, C. A., Berkowitz, L., Donnerstein, E., Huesmann, L., Johnson, J. D., et al. (2003). The influence of media violence on youth. Psycholog- ical Science in the Public Interest, 4, 81–110. Balk, D. E. (2004). Sharing our shock and grief. Death Studies, 28, 971–985.

- 67. Blanchard, E. B., Kuhn, E., Rowell, D. L., Hickling, E. J., Wittrock, D., et al. (2004). Studies of the vicarious traumatization of college students by the September 11th attacks: Effects of proximity, ex- posure, and connectedness. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42, 191–205. Brooks, K., Schiraldi, V., & Ziedenberg, J. (2000). School house hype: Two years later. Washington, DC: The Children’s Law Center and the Justice Policy Institute. Bushman, B., & Anderson, C. (2001). Media vio- lence and the American public. Scientific facts versus media misinformation. American Psychol- ogist, 56, 477– 489. Caprara, G. B., Renzi, P., Amolini, P., D’Imperio, G., & Travaglia, G. (1984). The eliciting cue value of ag- gressive slides reconsidered in a personological per- spective: The weapons effect and irritability. Euro- pean Journal of Social Psychology, 14, 313–322. Chiricos, T., Eschholz, S., & Gertz, M. (1997). Crime, news, and rear of crime: Toward an Iden- tification of audience effects. Social Problems, 44, 342–357. Chiricos, T., Padgett, K., & Gertz, M. (2006). Fear, TV news, and the reality of crime. Criminol- ogy, 38, 755–786. Coyne, S. M., & Archer, J. (2005). The relationship between indirect and physical aggression on tele- vision and in real life. Social Development, 14,

- 68. 324 –338. Gil-Rivas, V., Holman. E. A., & Silver, R. C. (2004). Adolescent vulnerability following the September 11th terrorist attacks: A study of parents and their children. Applied Developmental Science, 8, 130 – 142. 229EFFECTS OF VICARIOUS EXPOSURE TO VIRGINIA TECH Green, W. (2003). Econometric analysis (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Hausmann, J., & McFadden, D. (1984). Specification tests for the multinomial logit model. Economet- rica, 52, 1219 –1240. Huesmann, L. R., Moise-Titus, J., Podolski, C., & Eron, L. D. (2003). Longitudinal relations between chil- dren’s exposure to TV violence and their aggressive and violent behavior in young adulthood: 1977– 1992. Developmental Psychology, 39, 201–221. Langua, L. J., Long, A. C., Smith, K. I., & Meltzoff, A. N. (2005). Pre-attack symptomatology and tem- perament as predictors of children’s responses to the September 11 terrorist attacks. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46, 631– 645. Long, J. (1997). Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- 69. Long, J., & Freese, J. (2003). Regression models for categorical dependent variables using strata. Col- lege Station, TX: Strata Corporation. Maddala, G. (1983). Limited dependent and qualita- tive variables in econometrics. New York: Cam- bridge University Press. Mason, W. (2004). The holes in his head. Retrieved September 11, 2007, from http://www.tnr.com/ doc.mhtml?i� 20040927&s� mason092704 Mickey, J., & Greenland, S. (1989). A study of the impact of confounder-selection Criteria on effect estimation. American Journal of Epidemiology, 129, 125–137. Paik, H., & Comstock, G. (1994). The effects of television violence on antisocial behavior: A meta- analysis. Communication Research, 21, 516 –546. Peck, E. Y. (1999). Gender differences in film- induced fear as a function of type of emotion Measure and stimulus content: A meta-analysis and laboratory study. Unpublished doctoral disser- tation, University of Wisconsin, Madison. Pfefferbaum, B., Gurwitch, R. H., McDonald, N. B., Leftwich, M. J. T., Sconzo, G. M., et al. (2000). Posttraumatic stress among young children after the death of a friend or acquaintance in a terrorist bombing. Psychiatric Services, 51, 386 –388. Pfefferbaum, B., Seale, T. W., McDonald, N. B., Brandt, E. N., Rainwater, S. M., et al. (2000). Posttraumatic stress two years after the Oklahoma