This document provides an overview of an issue of Architectural Record from May 1976 that focuses on improving living conditions for the urban poor in developing countries. It summarizes the background and goals of an international design competition held to address the urgent issue of rapid urbanization and the growth of slums and squatter settlements. The issue features the winning designs from the competition and discussions on new strategies to upgrade settlements that combine community participation with minimal government intervention. It aims to draw global attention to solutions for housing the billions of people expected to live in cities in developing nations by the year 2000.

![AR(HiTECTURAL RECORD MAY 1976

. BUILDING TYP(S STUDY ® 488

., '·'• '

- ~--~ ~ 1

just overctwo yéar~ ago, in. theJpril 'l974 issue, ARCHITECTU~AL RECORD announced

th~ formation ofthe non-profit lnternational Aré:hitectu1·al Foundation for the p.ur-

. pose of '~organizing an 'interriatiqnal ' design COmpetition for the urban envi/Ofl~

entóf deVeloping countries."That prqject, conceived by the staffs of RECORD and

L'Architecture d'Aujourd'hui, is intended to focus the attention of architects and

planners around the' world ·on the accelerátiiíg urban crisis in developing countries,

to encourage thedevelopn1entof thoughtful prototypical designs for housing

and community development, and to make the results of this effort known ·

throughout the world . In the hope thatthe resu lts of the design' competition do

"help make a world where hope makes sense," we present this issue to architécts,

planners, iriterr.tational aid and lending agencies, and government officials around

the world-on behalf of more :than a billion people who live in urban slums. ·

1 HUMAN

SETTlEMENTS

.--··

... an issue c:oncentrating on one of the urgent problerns of our time, with the winning designs in

The lnternational Design CmnpetitiO"~ for the Urban .Environrnent of Developing Countries .

¡

lnthe developing countries around the world, millions of families haye moved from the countryside

to the cities in hope of jobs, education, and a better standard of li ving-and instead have

found only a different k,i;~d of deprivation. N.owhere are the global problems of excessive population

. growth, unemployment, environmental decay, al.ienation, and urban squalür,;· more clearly

focused than in the urbansiums that have resu!ted. This . unpreceJent~d transition from rural to

urban societies has vast national and global repercussions-social, economic,, and pójitical.

As sen ior editor (and competition .juror) Mildred Schmertz points out in her article beginning

overleaf, there is new hope and new direction in efforts to help the urban poor. Her article-and

the phcito essay on page 100 by noted social scientist Aprodicid Laquian---{]escribes and evaluates

the principal strategies by which the devejoping countries are seeking to improve squatter settlements-

and focuses on the great promise of new strategies which combine sensitive and mínimum

governmental intervention with squatter community self-help. •

These new strategies were the basis for the cpmpetition program~eveloped with the assistance

and enthusiastic súpport of the f?hilippine govérnment, which agreed to build the winning

designas a prototype in a plann~d redevelopment in Manila for 140,000 squatters. The competition

si te and it,s people~the framework for the competition-is described on page 106.

The competition, clearly the most sign ificant design competition of its kind ever held, also

proved to be one of the largest. An astonishing 2,531 registrations- from 68 countries-were

~eceived ; and 476 submissions were judged by a distinguished international jury (see page. 112).

The winning designs-and a number of unpremiated entries-are shown beginnin'g on page '114.

Finally, beginning on page· 156, is· a sumhlation that indudes an anthology of comments by

world l<;aders in the struggle·to improve the cond itions of the world's urban poor, the report of

'the jury, and an analysis by the editors of the significant achieverrients of the competition and

s'~eculation on its possible impac;:t on the futuré ~~ urban development around the world.

' ~-· · As we wrote in our first ed itorial on the competition two years ago: "We are not so naive

asto believe that arc'hitecture is the solution to all the problems ofthe world; that good planning

and design is a s'ubstitute for joqs that don't exist, or -food that does not exist or is too dear. But

housin'g and a sense of community are basic human needs-and that is the part of the problern

tllat we [the RECORD staff and architects everywhr:re] know most about and can best do something

ab~ut. So let us try .. : . ' ~ · . . · . .· . .., .

This issue is the result of two years of trying by literal! y thousands of people. '-V1. W

ARCH iTECTL!RA.L RECORD ,VIay 7976 95

1,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/architecturalrecords-140908105306-phpapp02/85/Architectural-records-1-320.jpg)

![,_

Many squatters and sl.um dw~Uers

leave picturesqu~ villages

_arid neat hom~s to-move to the citY.

Some are pushedóut by rural poverty

-,-but most .are attracted

by what the city offers .

. . . jobs, education.for their children,

new opportunities, and e_ntertainment and

excitement. What the migrant needs

is a toehold into urban life-and this happens ,.

when heiinds shelter, a job, anda

socia/.lífe in a commúnity of fellow migrants

. who bringwith thein thewarmth and pride

of a rural village.

A strong reason for urban migration is

rural poverty A cluster of huts in a

minihmdio in Mexico where a family usual/y

tills less than a hectare (2.5 -acres) of /and

shows the_ poverty .of rural people. Each year,

. ·tho_us¡¡nds of campesinos move to cities,

· éoritributing to_ the primacy of Mexico City.

A migrant's toehold may be a squatter shanty,

· such as these makeshift dwe/lings bui!t

by invading "parachutists" inMexico City.·

lt may be a hillside of adobe shantiés,

shown ¡¡t far left, in Bogotá, Colombia.

An interesting phenomenon in lbadan,

Nigeria, are the many "Brazilian" houses

built by returnedslaves and migrants. These

large fiouses are internally subdivided

-into renta/ units, T/]is particular house .

has more_than,tw.o dozen farr¡i/ies whp share

commori baÍhrqom and-kitchen faci/iiie~- '-'

Dr. Laquian is assoóate direCtor, Social Sciences and ··

r:tuman Rest~lUrces, _ of ' th~ lntern3-tional Developrnent R~

search Centre of Ottawa. B~rn in a village and raised in a

Manila slum, he gr~duated from the University of the PhiliQpíñes

in Manila in public administration/ and receivetf his

doctorate in political science from the Massach~setts inS:titute

of Technology. He is the author of many imponint p~b~

tications on housing for the poor and, rural ITlígr~t!on, and

has conducted two majar field studies in deveiÓ.piAg coun' .

tries on patterns of migration and housíng for fherural and

urban poor.

ARCHITECTURAL RECORD May 197_6 - 101](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/architecturalrecords-140908105306-phpapp02/85/Architectural-records-7-320.jpg)

![~--:_)j,;;J.r-;""l

p-r0~<J¡;):r-1

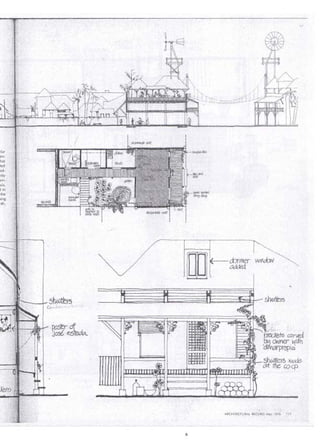

The first-prize-winning design by lan Atllfield . . ( LA -~~-0·'·-''c

of Ne".f ;-?~aland proposes_f_9r é~rh "barangar, a new 0kf~(tof workJJI .

>=,;)- {;,._ _ /' ..~. -..· · .• ._E..-.-._a~~ dA... 7 Q_.~---~,_,--Y.../-'-~~1...-~ . . ' Uv--r~e,.....-.~-;· --·'---?-:.~..;? _7~ ~~- (l.,_ .

- a penphery of hnear bulld1ngs LC~u.__. d~sugneo for a comb1nahon

.. _'--.A:_ ._ ..._-.'X......,...-"-. 8

otc6tt~fe, light, añd non-pOíf~tiilg~eJ

industries vy!th community ga~d~ns on top

r ~--··.&:.----- . ..:.> .... l--1 /- r:-~ , i /?'' , , ......, , . · 1 ·-:---¡-- ,... 1 ~ ...f" QD

-~-·- L•. -L:/__.[L-L' ;.··. '- vV./---J_/..~ (?'~•..._.,.(..A._..{_¿..¡_.;,_~I.....-!.-: ..... ~ ~~ 4='--"'L.!t.J-'..~

The jury awarded first prize to lan

Athfield, a young Ne'f~ Zro0 lanrL

. !!'r'GcérOJO ·

arch1tect, for. a tourageous pro-posa!

tlli:lt makes .the workplace of

the community the majar control~

lingelement of the design. This 'introduction

of job-generating space

is a truly new concept a~d represents

a genuine advance in · the

physical planning for human settlements.

This work space should

significantly help the lnhabitants

of the Dagat-Dagatan b.arangays

to transform themselves intó a

self-sufficient community.

Accord ing to Athfield, this

working perjphery (see site plan

and sections right and overleaf)

would be the first part of each

community to be built. lt would

· be a significant addition to the

customary installation of sites and

services - the goyernment-supplied

infrastructure bf roads, sew.ers,

piped water and electricity.

· ~he pepple movi:1~ g?}?a,gatDagatan

vvould help eréd"' this

working periphery in increments

as ~eeded. A particular ' area

within each working periphery

would be reserved for a building

cooperative ruh by the loca l residents.

This cooperative would ini-

. tially control.thesupply-,. manufacture

ancl use of building materials

for the barangay. Households possessing

existing building materials,

in the form./ of their prese,1]t

shanties, coulcl trade these in at

the cooperative, which would arrange

tlie recyding of such materials.

The cooperative, by li'miting

the range and variety of the buildiilg

rnaterials to be mqcle avail- .

able, could help achleve a consistency

and upity in the design and

a¡:ipearance of the housing units.

As the cofnmunity develops,

the roie of the building cÓoperative

cóuld bmaden to include the

provision of cither building e l e~

ments, and td supply a market

beyond the initial comrnunity,

114 ARCHITECTURAL RECORD May 1976

thus increasing the number of jobs where individuals coulcl be

available. 'Sp'ace within the work-!. trained in alternative energy· and

ing periphery would also be recycling techniques. liidividual

leased to private.light indústries,: industries ancl households would

thus bringing even more jobs· to be ' encouraged by a small pay"

the barai?gays: ment to send all their wastes to the

Athfield proposed that the' energy cénter. As awarenéss aiid

families of any person obtaining 'understanding of the waste and

employment In the working pe~ energy systems clevelops; familie5 ·

riphery would have priofity in ob- would be encouraged a lid assistecl

taining a house si te in the baran-, td cliwelop their own conservation

gay. He has calculated that beJ andenergy plants.

tween 300 ¡md 400 people could , Each energy centerwould be.

be employed for every 10,000 ' looked after by a caretaker. Windsquare

meters (1 07,600 square : milis for the energy centers' would

feet) of working space surrouncl~ ~l2>cated ori the roof oftÍle woi·king

each .bara;1gay. Given apprdx" ing perimeters adjo!n.ingJ:ommuimately

188,300 square feet o.f . nity'"'gardens also located there.

working perimeter, between 550 ,, The gardens and energy centers

and 700 persons of'thé SQO fami ~ would be a .strikingly visible exlíes

living in each par¡uigay would 'pression o(tle --éoope1·ative

have j,obs within walking distance • achieitements'of the community.

of their homes. AthfieÍd points out. The working perimeter will ·

that the place of work and the serve as a ?trong physical ..!?,g.uGcf:.

home should be closely assoc -~Y for e,ach barangay. As Athfield

ciated to récluce the time and cost r(Jóln!~ .. <OLi't within the. Philippines

of commuting to.work, but justas 'tiléiAiaiÍhas been a strong element

irnportantly, to encourage cooper• of design definition as well as se~

ation within the .community itself:· curity..from the begirining of the

The working peripherywould · · Spanish influence. The perimeter

2!so contain 5eV¡>ral community structures ' around each barangay

energy centers (pages 120-1 21) .will help shape lively streets bec

from which thé conservation of tween · thenl. These streets will

energy could be .d'irectécl and . have the qlliJ,Iity of the pedestrian

l~n Athfield (front and

éenler) founded Athfield

. Architects in 1968:

(leflto :igh() MoyraTodd,

Wal Edwards, Graerne Bouche,

.Ddri Báird and lan -Dick-son.

Absent is Ti m Nees.

B'ónÍ in Christchurch,

New Ze~land in 1940, '

Athfield ·earned his ',

Diploma of Ardiitecture

frorn .Auckland School of

/rch•tecture in 1963.

A profile of Athfield and

his work i? on pages 42-43.

-- - - --~~----------

passageways of pre-automobile" :

age cities ancl towns-'-'alive with

workshops, : small sto1'es, markets

ancl food star1eJs.

Athfielcl's house cfes ignsdetti- ·

onstrate, .in the opinion o! the jury,

" his sensitiyity to the cu lture ancl

life style of.the comrnunity and its '

'asp iratlons." Occupying individual

siies, iwhich would average 55

squar~ n¡etersJ?~1'. scjuare. f~~t) ,, :

each, the d1véltiñgs can be 1bVilt'.l0 ·.

by the fesidents ihemselves ·:at

1 '· ' . '

their present state of competence

as craftsri1e1i; witlií11 the- tr¡¡¡ditioni

rural Shiidii;g"vernacular of

the Ph ilippines (pages 116-12'1)., ·

Athfield urges that the si te$ be .·

leased to 'thé newinhabitants with ·

eventual rights of ownership. His .

deeply a ii~Jsi'e and .· expressive

drawings show how the bara_rígay. ·

houses cou lcl look alter the farni~'i

l~? . l;ave beet1secure in thern foi ·:

aVhile. As length .of lenure; effort' ·

and investment increase, gardens·.·.

and trees are planteo. 'The houses .

expand to in elude small verandás; "

kitchen and laundry e.quipment is

improved; better 'furnishings are <

purchased; potted plants apiJear

and pictures clecorate the wa}ls.

Doon< window frames and shut-· ·

ters/ made at the.builcling materi:

als :coopera ti ve and. purchaséd in

stages by the niigrant as he graclu- · ·

;.:!!y beE:omes .able to afford ·

t)lem-.-:.coritribute to the. so!idity ·

ánd permanence"of his house. As

' his, family grows and his ~ eco- ..

nomic positi()n iriiproves,, the . in-'-

habitant's house grows to éxpress

his owri and his f~1r1ily'~ expand.

ing'needs and rising aspirations.

In his submission, Athfielcf

proposes that his winning desigri · .

team work with each f<~mliY to

gíve advice on boundary situa:.

tions, erection procedures an.d

building techniques. He sees this

di'rect work with the community

as the principal ancl most challenging

task 61 the desi~n tea¡n.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/architecturalrecords-140908105306-phpapp02/85/Architectural-records-20-320.jpg)

![----------- ·~·- '.

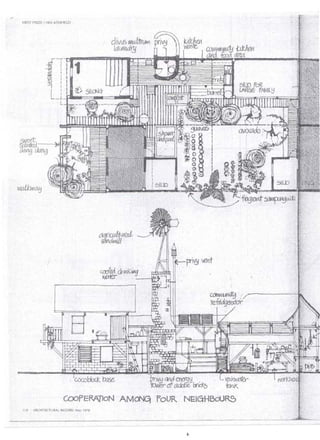

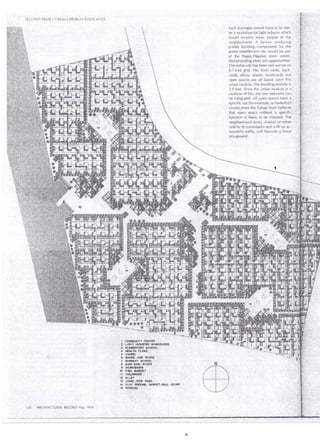

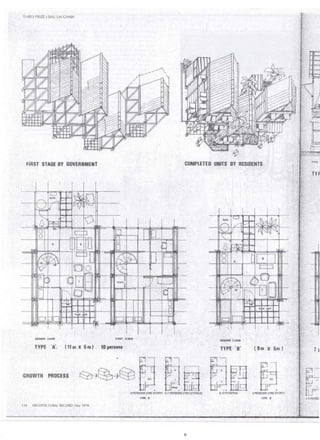

SECONO PRIZE 1 TiKAG I OESIGN ASSOCIATES

__ .... -]

k

1 1 1 1 ¡ 1! 1 1 1 1 1 - 1 1 ' '1 11 1 1 1 1 1 J 1 1 11111 1 lll 11

~ -~ L h ...

-.'.--1 1· . J

... <tf )'-!

p §[}g u_,g ....

.r-mm • . . , rn:rnr- nm~ ' ~

1 -r .. · ,_..;

' f..J

1 ~- -1

-:-.. "' fD < .. ......J:l 1 ~~}jl t'"... i ¡- ' ~- l'- t(l ~-i!Ji ~"-iJ ~- 1 '-~ .J ~ .....

-~ ~ .;; • ..

~ •

_,;¡, ~ [,.(,:~ ..¡, ~ ~- 1:-. y ·i:;rl- ,r ~~

)o

~

r.. r~ l ¡ ¡ 1 1 11 l 1 i 1 J ¡ 1 !1

~~Ji r~ ca;J . 1'1 1'-lh 1'

- . . ; '..:.. ., . :1• ~ ~ ÍP lff¡¡ t::>¡::;::: .----.

... .n:mr. -- . Q :mil ·t: r~ imn. . ! ¡;=¡

•

F ~ ~- v ~ ,. ' .. - . tUlllU __ IJ.¡Jij'

~· ~ FH .. J · .. 1 r ~; L F

r nr rrlll'lllll nrr1 111 ' ' 1 1111 . 1 1 11111 11111 11-

OWER . UPPER

LOOR FLOOR ,..IIIÍiillli](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/architecturalrecords-140908105306-phpapp02/85/Architectural-records-34-320.jpg)

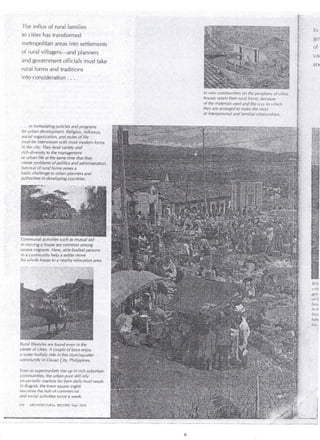

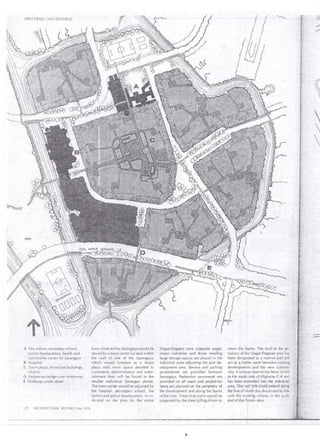

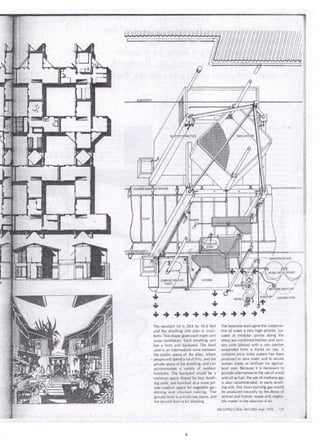

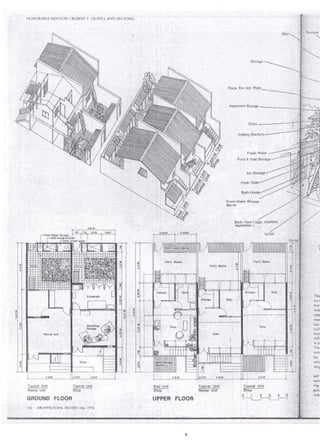

![This_ honorable mention scheme by

San Francisco architects Holl, Tanner and Cropper

organizes the competition .site with

a simple series of arcades--"a line that

defines public and private spaces"

This design shares with the winning

scherne by lan Athfield - the

impulse to add sorne special ele"

rnent of infrastructure to the usual

site planning and se rvices_ Here

that special elernent is a long arcade

(below) that wends its way

through the site and is capable of

delailed development by the inhabitants

of the barangay (as is

projected from left to right in the

drawing below)_ Here, in contrast

tó the first-prize design, the basic organizational

structure js through

the center: of the si te -rather than

1. INITIAL CONSTRUCTION-around

its edges-"-a spine that, according

to the architects, defines

public and private:spaces Importan

tó this scherne as well is the

notion of "fan;ily_- tenure"-th-e

- possession of individu¡J.I parcéls_of

land by relocatéd inhabitanis, so

that the energy and comii1itment

required to develop, them b,eyond

the bare essentials provided in the

design can be stirnulated by the

-certainty of permanent posses:

sion, The arcade-or paseo--pro-vides

the unifying socio-commei'tial

fulcrum for this investrnent

LOT. UNES, UTILITY MAINS (STUBS FOR ALL UNITS) -COMMUNITY

BUILDINGS: WASH HOUSES, EDUCATION

CENTERS, COMMUNITY WATER SOURCES

í . ]' ', 1

2. EARL Y RELOCATION _0F EXISTING COMMUNITIES l

TEM PORARY PRIVA TE LA TRINES IN GARDENS

1 ' 1

3- ELECTRICITY CONNECTEO 1 1

1

4_ WASTEDIGESTERS INSTÁLLED-

5_ WATER & WASTEWATER LIN,ES éONNECTED

1 1:

·1

- 1

1

1

Steven M. Holl, james L. Tanner_ahd j0hn Cropper fortned

themselves irito a team to develop their submission-in a rented

room in San Francisco. Hall ·va~ educated at th~ University

of Washington and is currently in reseai-ch at the Architectural

Association in London;.Tanner was educated at·the University of

Houston and has worked for firms there and in San Francisc~;

Cropper was educated in England and practices in San Francisco_

1

:--s- -_---

1 -

1 .

_1 ' -, lA:·

,:; '

1 '

1 -:

1

1 1 - - '

-- -- - J.. - -¡- - - - L - . -

b'(::'d PU8LICSPACE

t== FIRE-RATED WALLc:

«?í'~j WASTE DIGESTER

1

_¡ ___ _ o _¡ T L_ __ !JT~

1 1

' 1 1 ------- ~- -- -- ~-- ¡- ~-¡

1

136 :ARCHITECTURAL RECORD May 1976](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/architecturalrecords-140908105306-phpapp02/85/Architectural-records-42-320.jpg)

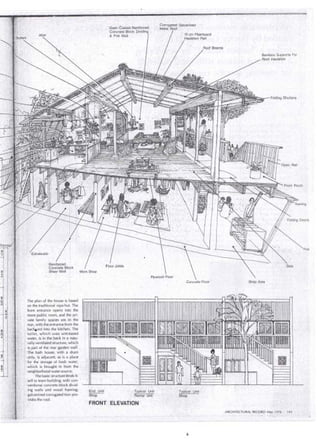

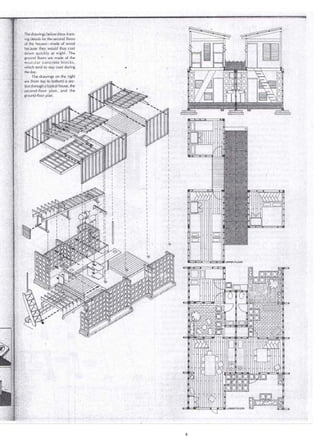

![.. Exarnpl.e::tliesestrong

·precast.concreteJrames

· ,. •. . 1

·• to.support tenantsÍ own

con~truction, pro~osed

qy a tea m headed lb y

• 1

, 'architect Gerald Jbnas

TIE ROO

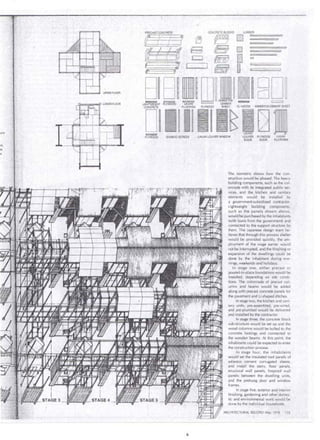

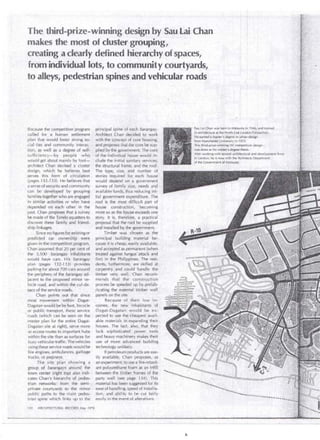

Submitted by a New Yor)< City . to ·.be ·maneuvered to prepared

team, that inc!uded an éngineer, · footings by teams of tenahts; there

· this proposal-notsurprisingly-' · they would be as·sembled to form

contained a. high.)evel of innova- rigid frames of Úp to tvvo-and-tive

teChnical · input Addressing a-half-stories (drawing ·below)

.the problem of the structural · connected to the .footings by tie

SOUndneSS Qf tenants' OWf) C()n- . rods. (;rooved surfacés in the

struction in an a,rea subjec(to ty- trames would allow an interlock-phocins;

Gerald Jcinas, Hénry S te- inginfill of :,.;óoden floors and of

phehs~n, J~ff "anderberg and Sil- ~a!ls oí any· ava ilablé . m¡¡terial;

vian ·Marcus proposeci that each from concrete bloc~ to corrugated

.homesteéldei pe Sljpplied with ·a metal to -woven barnboo. · One

basic :Set óf 16 concrete l.J -shaped . wall and one plan k floor of con-c<:

irnpqnents, plus .beams, 'planks cret~ -.yoyld provide braci11g.

arid a concrete pracing panel. In the proposai,'the architects

These .elements; financeq .by the · · emphasiÚid · fle~ibility. The progovernm~

nt and d1st cin the sita, ¡:irietary strüctures ca[] be skewed

_ wciuld be srn.alland ligh¡enough to adapt'to irregula,r lo¡lines. The

CONNECTING

?elt Help .lhfi 11

only precision task is the leveling

and spacing of footings. Upgrading

of the encloswre materi als can

be accomplished in increments

according tO the abilities.of the inhabitants,

and qoes not require

basic rebuilding. The architects

also emphasized the long-term

económies of . investment in perrnanent

re-usable parts, the shortterrn

economies · of the labor-intensiva

fabrication with erectior)

of the parts by . residents, and the

possibility of an on-going eco~

omic benefít to the residents in

having an ' oh-site industry fabrica

te the concrete elements for

otlier sites.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/architecturalrecords-140908105306-phpapp02/85/Architectural-records-55-320.jpg)

![• 1

• 1

. pose. We must identify/ policies

·and actiohs to bring thi~1abóut.

~¡',

· as such. They should neither be

looked down upon in regard to

thelr standards, technical suffi-

.• .- .

.... "" .

ha.ye the courage to squarely fa ce

. this re~lity and to act accordingly?

Enrique Peñalosa, dency,. or lack of infrastructure; ).W. MacNeÜI,

Secretary-Gerr2ral nor as regards their differences Commissioner General

· HABiTAT/United Nations ' with the organized city. Converse-~~ of HABIT AT for Canada;

,i ::..<confen~~ce . ly, the ingenuity Ófthe inhabitants . At the HABITAT ccínference, one

. ~· -: on Human .Settlements: need not be magnified nor their of thé mbstlmpprtant elements iri :;: i. .· unplam~ed urbanization is the spontaneity exaggerated. The pro, the search for. s'olutions to low"inF't

,-·¡ypical form of urban growth in fessiona:l ·bodies must recognize come urbaw settlements will be

:--,-.-,.r:

problems of whole communities,

induding low-income families .

Similar cbmpetitions to this one

for Manila should be held in the

other developing regions.

The competition suggests that

many universities and specialized

faculties wciuld do well · to consider

major modif>Ícations of their

programs to take account or the

pJ the Third World. lt:will probably and work with squatter settle- the sWdy ofmethúds for the pre"

human settlerilents" thrtJst. q,, :increase; as ~ill the pr?portion of merús ás they are. · -- ·· plannihgqfsquatter·settlements to

'self-built shelter: This does not · lt i's in the impróvement of the · meet minirmiril needs. In nations Hel.ena Z. Benitez, president,

· iliake professiónal planners . Ll ·n~ deslgn·and production ot the ele- With low average in comes and 111 Governing Cot.incil, ·

necessary. 'Quite the COI')trary: ments ·alid corriponents of shelter minimal purchasing power, it is Unitéd Nations Envirorm1ent

.since they are able to uhderstand ' that the professional bodies can . possible to help people to create Programme;and president,

}hé phenomenoh, in depth, plan- contribute positively. Tbis produc- .decent livablé cornmunities wlth Philippine Women's

ners are alreagy badly needed in tibn must be geared to the eco- basic shelter, a sale water supply, University, Manila:

. the roles of .i.nterpreter and Gita- noinic capacity óf ·the -population sanitary waste disposal, trans- The exhibit of the leading en tries

· .lyst. Planners · can -explaih the .· botli"at the household and the na- portation,. and health arid educa- of the IAF competition will be an

·squatter problerti and its real di- ticinai· leve!. ltis useless to intro- ... tion services. Such pre-planning outstanding contributiori'· to the

. rnensions to .the a~,Jthoríties, witn a duce a technical .solution outside would represen! a m¡¡jor step for- Vancouver HABITAT scene. Un-viewto

cónvincjng them .of the in- the limits of family income or the ward for millions of people. fortunately, the resources of all .

vestment involved in these settle- traditions and aspirations of tfie i am therefore glad to wel- United Nations agencies· are now

ments; of the lack .óf immédiaté cciuntry ~nd its people. come the IAF competition initia- · stretched thin, ánd there is little tci

· housingal'térnati~edor the squat- . . . . tive iri the conscious design of spare for the more extensive efioi·t

te.rs, and therefore of the J.G. van Putten,- ~hairman, squatter settlements. for broad human settlements im-

. catastrophic cbnseque·nces of . Non-Gove~nmental provement which such a competi-demolition.

·· · · Organization's committee for · C..EricCarlson, deputy director, tion inspires.

PlannirÍg prófessionals cari , HA~ITAT; · Divisio'n of Financia! To augr'nent thé UN Habitat and

persuad¿· .thé· authorities to pro- T.he IAF lntern¡¡tiónal Design and Technical Services, Human Settlements Fouhdation's

vide thóse services and facilities Competitlon .has generated note- United Nations HA BIT AT and efforts,ne'w instruments should be

which are technically;,financially,. worthy ideas about tfie use of ma, ·Human Settlements Foundation: created, perhaps involving much

and ·adrpinistratively impossible .terials, the ~ppÍication of self~help The results, meanirig ahd ·impact, greater private sector partici'

for .the ·squátters to fúrn ish them- · elements, the coriservation of nat- of the IAF . International Design pation. After all, human sett/e"

. ]'. se lveswithciut help. ural resources and .the safeguard- Competition speak for themselves. ments irnprovement could be the .

O~; Y> Plarine;s ·can also help the · ing of yaiLi¡¡ble commuhity é:har- For the whóle HABITAT exercise, world's ·greatest growth industry.

i) · squatters in théir fight for security · acteristics: they provide a les son in partici- The need is urgent, beta use

'L' ;of tenure in order to legalize the The coriipetition demon- pation~by having en listed the in- people can and must acquire· a

5 ' settlemerits and relieve the squat- strates that májortechnical prob- . terest, supp6rt and sponsorship of stakeintheir habitat. . ' . . ·

;¡t,: • ters of the ahxiety of illegality. : léms can be sol ved. One can only the private seCtor for broad public . There should be more inter,

,,·.· ·. Finally, the professionals can be glad that the 17,000 families purposes, as well as by mobilizing hationa,l design competitions for ·

i~, persuade the authorities that, even that will be resettled on the Dagat~ the ehthusiasm, experience and environri1entally- balanced com-

·f<:: for· squatter settlements, long-term Daga tan si te will be able to profit dedication· of thousands of con- mul')i.ties in . both the rural and :+·,, plans are possible and thiH the from this effort. However; technÍ- c~r~ed' professionals through~ut urban are as of developing coun,_

;1-:f'; go.vernments concerned should cal solutiohs are one· thing; the the world. Looking ahead, we can· tries. From these efforts will

('~··organize relevant legal, adminis- possibility to apply therri on a see that future international design · .emerge demonstration projects'''

~):> irative, · financia! and technical large scale; another. competitionswill ha ve real usefulc . ' reády for incorporation into ,lof']g- .. , té· rnechanisms instead of constantly A real solutiori of the squatter ness not only for th.e desigh of ¡ térm economic, social a;,d· en~ ·'.

;~:/: being taken by surprise. problem cannot be brought abbut major natiélnal .and international : yirÓnm~ntal programs ba·~~d Úpcin

[>;.:: '. ':. Squatter settlements are in- without taking into · consideration ' structures, ,..;_,hich 'has bei:!'n their. ;: · broádly conceived nationªl $trá'té-pl::

C~~p~rabl y part oí human settle- its economic and social context. role. in the past, b~tfor helpin.gtp: gies fo'r human settlernelits loca-.'"

)':_me11ts and they must be accepted Will the HABITAT 'conference provide solutions tb tllf; basic , tion and development. . } : ·

·: ARC::HITECTURAL RECORD !vlay '1976 ·

• j .~](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/architecturalrecords-140908105306-phpapp02/85/Architectural-records-64-320.jpg)