Copyright 2014 American Medical Association. All rights reserv.docx

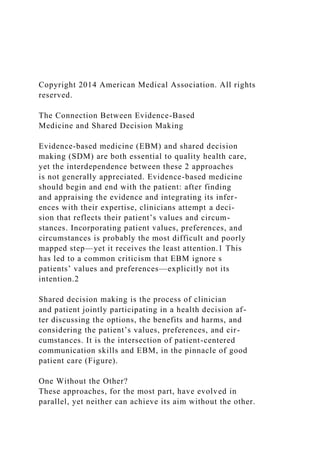

- 1. Copyright 2014 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. The Connection Between Evidence-Based Medicine and Shared Decision Making Evidence-based medicine (EBM) and shared decision making (SDM) are both essential to quality health care, yet the interdependence between these 2 approaches is not generally appreciated. Evidence-based medicine should begin and end with the patient: after finding and appraising the evidence and integrating its infer- ences with their expertise, clinicians attempt a deci- sion that reflects their patient’s values and circum- stances. Incorporating patient values, preferences, and circumstances is probably the most difficult and poorly mapped step—yet it receives the least attention.1 This has led to a common criticism that EBM ignore s patients’ values and preferences—explicitly not its intention.2 Shared decision making is the process of clinician and patient jointly participating in a health decision af- ter discussing the options, the benefits and harms, and considering the patient’s values, preferences, and cir- cumstances. It is the intersection of patient-centered communication skills and EBM, in the pinnacle of good patient care (Figure). One Without the Other? These approaches, for the most part, have evolved in parallel, yet neither can achieve its aim without the other.

- 2. Without SDM, authentic EBM cannot occur.3 It is a mechanism by which evidence can be explicitly brought into the consultation and discussed with the patient. Even if clinicians attempt to incorporate patient prefer- ences into decisions, they sometimes erroneously guess them. However, it is through evidence-informed deliberations that patients construct informed prefer- ences. For patients who have to implement the deci- sion and live with the consequences, it may be more per- tinent to realize that it is through this process that patients incorporate the evidence and expertise of the clinician, along with their values and preferences, into their decision-making. Without SDM, EBM can turn into evidence tyranny. Without SDM, evidence may poorly translate into practice and improved outcomes. Likewise, without attention to the principles of EBM, SDM becomes limited because a number of its steps are inextricably linked to the evidence. For example, discus- sions with patients about the natural history of the con- dition, the possible options, the benefits and harms of each, and a quantification of these must be informed by the best available research evidence. If SDM does not in- corporate this body of evidence, the preferences that pa- tients express may not be based on reliable estimates of the risks and benefits of the options, and the result- ing decisions not truly informed. Why Is There a Disconnect? A contributor to the existing disconnect between EBM and SDM may be that leaders, researchers, and teach- ers of EBM, and those of SDM, originated from, and his- torically tended to practice, research, publish, and col- laborate, in different clusters. Some forms of SDM have

- 3. emerged from patient communication, with much of its research presented in conferences and journals in this field. A seminal paper in 19974 conceptualized SDM as a model of treatment decision making and as a patient- clinician communication skill. However, it did so with- out any connection to EBM—perhaps not surprisingly, be- cause EBM was in its infancy.2 Conversely, with its origins in clinical epidemiology, much of the focus of EBM has been on methods and resources to facilitate locating, appraising, and synthe- sizing evidence. There has been much less focus on dis- cussing this evidence with patients and engaging with them in its use (sometimes even disparagingly referred to as “soft” skills). Most of the EBM attention has involved scandals (eg, unpublished data, results “spin,” conflicts of interest) and the high technology mile- stones (eg, systems to make EBM better and easier). Information about using evidence in decision-making with patients has been scant. D i s c o n n e c t b e t w e e n t h e 2 a p - proaches is also evident in, and main- tained by, the teaching provided to clinicians and students, again often ref lec ting the backgrounds of their teachers. Opportunities to attend EBM teaching abound with content largely focused on forming questions and finding and criti- cally appraising evidence.5 Learning how to apply and integrate the evidence is usually absent, or mentioned in passing without skill training. Realizing the Connection Between EBM and SDM A logical place to start is by incorporating SDM skill train-

- 4. ing into EBM training. This will help to address not only the aforementioned deficits in EBM training but also the lack of SDM training opportunities presently available. Additionally, it may facilitate the uptake of SDM and, more broadly, evidence translation. Recent calls for SDM to be routinely incorporated into medical education pre- sent an immediate opportunity to capitalize on closely aligning the approaches. Without shared decision making, EBM can turn into evidence tyranny. VIEWPOINT Tammy C. Hoffmann, PhD Centre for Research in Evidence-Based Practice, Faculty of Health Sciences and Medicine, Bond University, Queensland, Australia; and University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia. Victor M. Montori, MD, MSc Knowledge and Evaluation Research (KER) Unit, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. Chris Del Mar, MD, FRACGP

- 5. Centre for Research in Evidence-Based Practice, Faculty of Health Sciences and Medicine, Bond University, Queensland, Australia. Viewpoint page 1293 Corresponding Author: Victor M. Montori, MD, MSc, Knowledge and Evaluation Research Unit, Mayo Clinic, 200 First St SW, Plummer 3-35, Rochester, MN 55905 (montori.victor @mayo.edu). Opinion jama.com JAMA October 1, 2014 Volume 312, Number 13 1295 Copyright 2014 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by a Walden University User on 01/12/2020 Copyright 2014 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

- 6. Another place to start to bring EBM and SDM together is the development and implementation of clinical practice guidelines. Whereas most guidelines fail to consider patients’ preferences in formulating their recommendations,6 some advise clinicians to talk with patients about the options but provide no guidance about how to do this and communicate the evidence in a way patients will understand. Shared decision making may be strongly r e c o m m e n d e d i n g u i d e l i n e s w h e n t h e o p t i o n s a r e c l o s e l y matched in their advantages and disadvantages, when uncer- tainty in the evidence impairs determination of a clearly superior approach, or when the balance of benefits and risks depends on patient action, such as adherence to medication, monitoring, and diet in patients using warfarin. Conclusions Links between EBM and SDM have until recently been largely ab- sent or at best implied. However, encouraging signs of interaction are emerging. For example, there has been some integration of the teaching of both,7 exploration about how guidelines can be adapted to facilitate SDM,8,9 and research and resource tools that recog- nize both approaches. Examples of the latter include research agenda and priority setting occurring in partnership with patients and cli- nicians to help provide relevant evidence for decision making; and

- 7. a new evidence criterion for the International Patient Decision Aids Standards requiring citation of systematically assembled and up- to-date bodies of evidence, with their trustworthiness appraised,10 thus aligning the development of SDM tools with contemporary re- quirements for the formulation of evidence-based guidelines. Also, independent flagship conferences focused on the practice of evi- dence-based health care and on the science of shared decision mak- ing are now convening joint meetings. Medicine cannot, and should not, be practiced without up-to- date evidence. Nor can medicine be practiced without knowing and respecting the informed preferences of patients. Clinicians, researchers, teachers, and patients need to be aware of and ac tively facilitate the interdependent relationship of these approaches. Evidence-based medicine needs SDM, and SDM needs EBM. Patients need both. ARTICLE INFORMATION Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Dr Montori reported serving on the board of the International Society for Evidence-based Healthcare; serving as Chair of the Seventh International Shared Decision Making Conference in 2013; that he is a member of the Steering Committee of the International Patient Decision

- 8. Aids Standards; and that he is a member of the GRADE Working Group. The KER Unit (Dr Montori’s research group) produces and tests evidence-based shared decision making tools that are freely available at http://shareddecisions.mayoclinic.org. Dr Hoffmann reported that she is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC)/Primary Health Care Research Evaluation and Development Career Development Fellowship (1033038), with funding provided by the Australian Department of Health and Ageing. Drs Hoffmann and Del Mar reported that they are coeditors of a book on evidence-based practice, for which they receive royalties. Additional Information: Additional information abut evidence-based medicine and shared decision making is available online in Evidence-Based Medicine: An Oral History at http://ebm .jamanetwork.com. REFERENCES 1. Straus SE, Jones G. What has evidence based medicine done for us? BMJ. 2004;329(7473):987- 988. 2. Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312(7023):71-72. 3. Greenhalgh T, Howick J, Maskrey N; Evidence Based Medicine Renaissance Group. Evidence based medicine: a movement in crisis? BMJ. 2014; 348:g3725.

- 9. 4. Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(5):681-692. 5. Meats E, Heneghan C, Crilly M, Glasziou P. Evidence-based medicine teaching in UK medical schools. Med Teach. 2009;31(4):332-337. 6. Montori VM, Brito JP, Murad MH. The optimal practice of evidence-based medicine: incorporating patient preferences in practice guidelines. JAMA. 2013;310(23):2503-2504. 7. Hoffmann TC, Bennett S, Tomsett C, Del Mar C. Brief training of student clinicians in shared decision making: a single-blind randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(6):844-849. 8. Decision Aids. MAGIC website. http://www .magicproject.org/decision-aids/. Accessed July 24, 2014. 9. van der Weijden T, Pieterse AH, Koelewijn-van Loon MS, et al. How can clinical practice guidelines be adapted to facilitate shared decision making? a qualitative key-informant study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(10):855-863. 10. Montori VM, LeBlanc A, Buchholz A, Stilwell DL, Tsapas A. Basing information on comprehensive, critically appraised, and up-to-date syntheses of the scientific evidence: a quality dimension of the International Patient Decision Aid Standards. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13 (suppl 2):S5.

- 10. Figure. The Interdependence of Evidence-Based Medicine and Shared Decision Making and the Need for Both as Part of Optimal Care Evidence-based medicine Optimal patient care Patient-centered communication skills Shared decision making Opinion Viewpoint 1296 JAMA October 1, 2014 Volume 312, Number 13 jama.com Copyright 2014 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by a Walden University User on 01/12/2020 Provider perspectives on the utility of a colorectal cancer screening decision aid for facilitating shared decision making Paul C. Schroy III MD MPH,* Shamini Mylvaganam MPH� and Peter Davidson MD� *Director of Clinical Research, Section of Gastroenterology,

- 11. Boston Medical Center, Boston, MA, �Study Coordinator, Section of Gastroenterology, Boston Medical Center, Boston, MA and �Clinical Director, Section of General Internal Medicine, Boston Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA Correspondence Paul C. Schroy III, MD MPH Boston Medical Center 85 E. Concord Street Suite 7715 Boston MA 02118 USA E-mail: [email protected] Accepted for publication 8 August 2011 Keywords: decision aids, informed decision making, shared decision making Abstract Background Decision aids for colorectal cancer (CRC)

- 12. screening have been shown to enable patients to identify a preferred screening option, but the extent to which such tools facilitate shared decision making (SDM) from the perspective of the provider is less well established. Objective Our goal was to elicit provider feedback regarding the impact of a CRC screening decision aid on SDM in the primary care setting. Methods Cross-sectional survey. Participants Primary care providers participating in a clinical trial evaluating the impact of a novel CRC screening decision aid on SDM and adherence. Main outcomes Perceptions of the impact of the tool on decision- making and implementation issues. Results Twenty-nine of 42 (71%) eligible providers responded, including 27 internists and two nurse practitioners. The majority

- 13. (>60%) felt that use of the tool complimented their usual approach, increased patient knowledge, helped patients identify a preferred screening option, improved the quality of decision making, saved time and increased patients� desire to get screened. Respondents were more neutral is their assessment of whether the tool improved the overall quality of the patient visit or patient satisfaction. Fewer than 50% felt that the tool would be easy to implement into their practices or that it would be widely used by their colleagues. Conclusion Decision aids for CRC screening can improve the quality and efficiency of SDM from the provider perspective but future use is likely to depend on the extent to which barriers to implementation can be addressed. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00730.x � 2011 John Wiley & Sons Ltd 27 Health Expectations, 17, pp.27–35

- 14. Introduction Engaging patients to participate in the decision- making process when confronted with prefer- ence-sensitive choices related to cancer screening or treatment is fundamental to the concept of patient-centred care endorsed by the Institute of Medicine, US Preventive Services Task Force and the Centers for Disease Control and Pre- vention. 1–3 Ideally, this process should occur within the context of shared decision making (SDM), whereby patients and their health-care providers form a partnership to exchange information, clarify values and negotiate a mutually agreeable medical decision. 4,5 SDM,

- 15. however, has been difficult to implement into routine clinical practice in part owing to lack of time, resources, clinician expertise and suitabil- ity for certain patients or clinical situations. 6,7 The use of patient-oriented decision aids outside of the context of the provider–patient interac- tion has been proposed as a potentially effective strategy for circumventing several of these bar- riers. 3,8 Decision aids are distinct from patient education programmes in that they serve as tools to enable patients to make an informed, value-concordant choice about a particular course of action based on an understanding of potential benefits, risks, probabilities and sci- entific uncertainty. 9–11 Besides facilitating

- 16. informed decision making (IDM), decision aids also have the potential to facilitate SDM by improving the quality and efficiency of the patient–provider encounter and by empowering users to participate in the decision-making process. 11 Studies to date have demonstrated that while decision aids enhance knowledge, reduce decisional conflict, increase involvement in the decision-making process and lead to informed value-based decisions, their impact on the quality of the decision, satisfaction with the decision making process and health outcomes remains unclear. 11 Besides enabling patients to make informed choices, decision aids also have the potential to facilitate SDM by improving the quality and

- 17. efficiency of the patient–provider encounter. Relatively few studies have examined the utility of decision aids for promoting effective SDM from the perspective of the provider. Studies to date have largely focused on provider perspec- tives on the quality of the decision tools themselves or issues related to implementation into clinical practice. 11–15 The overall objective of this study was to elicit provider feedback regarding the extent to which the use of a novel colorectal cancer (CRC) screening decision aid facilitated SDM in the primary care setting within the context of a randomized clinical trial. Methods Brief overview of decision aid and randomized

- 18. clinical trial Details of the decision aid, recruitment process, study design and secondary outcome results have been previously published. 16 The overall objective of the trial was to evaluate the impact of a novel computer-based decision aid on SDM and patient adherence to CRC screening rec- ommendations. The decision aid uses video- taped narratives and state-of-the-art graphics in digital video disc (DVD) format to convey key information about CRC and the importance of screening, compare each of five recommended screening options using both attribute- and option-based approaches, and elicit patient preferences. A modified version of the tool also incorporated the web-based �Your Disease Risk (YDR)� CRC risk assessment tool (http:// www.yourdiseaserisk.wustl.edu). To assess its

- 19. impact on SDM and screening adherence, average-risk, English-speaking patients 50– 75 years of age due for CRC screening were randomized to one of the two intervention arms (decision aid plus the YDR personalized risk assessment tool with feedback or decision aid alone) or a control arm, each of which involved an interactive computer session just prior to a scheduled visit with their primary care provider at either the Boston Medical Center or the South Boston Community Health Center. After completing the computer session, patients met with their providers to discuss screening and Colorectal cancer screening decision aid, P C Schroy, S Mylvaganam and P Davidson � 2011 John Wiley & Sons Ltd Health Expectations, 17, pp.27–35 28

- 20. identify a preferred screening strategy. Although providers were blinded to their patients� ran- domization status, they received written notifi- cation in the form of a hand-delivered flyer from all study patients acknowledging that they were participating in the �CRC decision aid study� to ensure that screening was discussed. Outcomes of interest were assessed using pre ⁄ post-tests, electronic medical record and administrative databases. The study to date has found that the tool enables users to identify a preferred screening option based on the relative values they place on individual test features, increases knowledge about CRC screening, increases sat- isfaction with the decision-making process and increases screening intentions compared to non- users. The study also finds that screening intentions and test ordering are negatively influenced in situations where patient and pro-

- 21. vider preferences differ. The tool�s impact on patient adherence awaits more complete follow- up data, which should be available in early 2011. Study design We conducted a cross-sectional survey of primary care providers participating in the ran- domized clinical trial in January and February of 2009. At the time of the survey, 725 eligible patients had been randomized to one of the three study arms. The surveys were distributed just prior to monthly business meetings conducted by the Sections of General Internal Medicine and Women�s Health at Boston Medical Center and Adult Medicine at the South Boston Com- munity Health Center. Respondents were asked to sign an attestation sheet if they completed the survey to identify providers not in attendance. For those who were not in attendance, the sur-

- 22. vey was distributed electronically as an email attachment; respondents were asked to return the survey via facsimile to preserve anonymity. Two email reminders with attached surveys were sent 2 weeks apart after the initial email to optimize response. The study was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Boards at both participating institutions. Subjects The survey sample included board-certified primary care providers (general internists and nurse practitioners) at Boston Medical Center and the South Boston Community Health Center who had referred patients to the randomized clinical trial. Of the 50 providers who had referred patients to the study since its commencement in 2005, 42 were still practicing at the participating sites at the time of the survey. All had exposure to

- 23. at least one patient in an intervention arm and at least one patient in the control arm; all but two of the targeted providers had multiple patients in each arm. None of the participants had formally reviewed the content of the decision aid nor received special training in SDM. Practice settings The Boston Medical Center is a private, non-profit academic medical centre affiliated with the Boston University School of Medicine, which serves a mostly minority patient population (only 28% White, non-Hispanic). The South Boston Com- munity Health Center is a community health centre affiliated with BMC, which serves a mostly White, non-Hispanic, low-income patient population. Survey instrument The survey instrument included a cover letter, 23 closed-ended questions and two open-ended

- 24. questions. Much of the content was derived from instruments used in previously published studies by Holmes-Rovner et al. and Graham et al. 6,15 The cover letter briefly described the purpose of the study, a statement that participation was completely voluntary, the approximate amount of time required to complete the survey, and a statement that all responses are anonymous and confidential. The closed-ended questions include one item related to eligibility [confirmation of participation in the clinical trial (yes ⁄ no)], two items related to demographics (provider degree and year of graduation), 12 items related to perspectives on the impact of the tool on various patient and provider components of SDM for Colorectal cancer screening decision aid, P C Schroy, S Mylvaganam and P Davidson � 2011 John Wiley & Sons Ltd Health Expectations, 17, pp.27–35

- 25. 29 CRC screening (see Table 1), and eight items related to perspectives on implementation or content modification (see Tables 2 and 3). The framing of the questions inferred a comparison between patients exposed to the decision aid and those not exposed, i.e., standard care patients, regardless of their involvement in the study. All of the items related to SDM used a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Six of the items related to implementation or content modification also used the same 5-point Likert scale, and two used a single best answer format. The two open-ended questions inquired about suggestions for improving the decision aid and complaints. The questionnaire took �10 min to complete.

- 26. Statistical analyses Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the study population and response data for all closed-ended questions. Frequency data for the 5-point Likert scale items were collapsed into three categories: �agreed ⁄ strongly agreed�, �neu- tral� and �disagreed ⁄ strongly disagreed�. Mean response scores ± standard deviations were also calculated for the same data using Micro- soft Excel functions. Responses to open-ended questions were summarized according to themes. Results Study population In total, 29 of the 42 (71%) possible providers, including 27 physicians and two nurse practitio- ners, responded to the survey and acknowledged that they had referred patients to the randomized clinical trial. Of the 29 respondents, 4 (14%) had received their degrees between 2000 and 2009, 15

- 27. (52%) between 1990 and 1999, and 6 (28%) before 1990; two declined to answer the question. Perspectives on SDM As shown in Table 2, the majority of providers (>60%) agreed or strongly agreed that the decision aid complemented their usual approach Table 1 Provider perspectives on the utility of the decision aid for facilitating SDM From my clinical perspective, the decision aid Response category, n (%) Mean item score (SD)* Strongly agree ⁄ agree Neutral Strongly disagree ⁄ disagree 4. Complemented my usual approach to CRC screening 24 (86) 4 (14) 0 4.3 ± 0.7

- 28. 5. Improved my usual approach to CRC screening 16 (59) 8 (30) 3 (11) 3.7 ± 1.0 6. Helped me tailor my counselling about CRC screening to my patient�s needs 12 (44) 11 (41) 4 (15) 3.5 ± 1.0 7. Saved me time 18 (64) 6 (21) 4 (14) 3.8 ± 1.0 8. Improved the quality of patient visits 14 (52) 9 (33) 4 (15) 3.6 ± 1.0 9. Increased my patients� satisfaction with my care 10 (40) 13 (52) 2 (8) 3.4 ± 0.8 10. Is an appropriate use of my patient�s clinic time 27 (93) 1 (3) 1 (3) 4.1 ± 0.6 11. Increase patient knowledge about the different CRC screening options 26 (90) 3 (10) 0 4.3 ± 0.6 12. Helped patients understand the benefits ⁄ risks of the recommended screening options 24 (83) 5 (17) 0 4.1 ± 0.7 13. Helped patients in identifying preferred screening option 21 (72) 7 (24) 1 (3) 4.0 ± 0.8 14. Improved the quality of the decision making 22 (79) 6 (21) 0 4.0 ± 0.7

- 29. 15. Increased patients� desire to get screened 21 (75) 5 (18) 2 (7) 3.9 ± 0.9 CRC, colorectal cancer; SD, standard deviation; SDM, shared decision making. *1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree. Colorectal cancer screening decision aid, P C Schroy, S Mylvaganam and P Davidson � 2011 John Wiley & Sons Ltd Health Expectations, 17, pp.27–35 30 to CRC screening, was an appropriate use of their patient�s clinic time, saved them time, increased patient knowledge about the various CRC screening options and their risks and benefits, helped the patients identify a preferred screening option, improved the quality of deci- sion making, and increased their patients� desire to get screened. Providers were more neutral in their assessment of the decision aid�s utility for improving their usual approach to CRC

- 30. screening, helping them tailor their counselling style to their patients� needs, improving the quality of patient visits, and increasing patient satisfaction with their care. Relatively few pro- viders disagreed or strongly disagreed with any of these measures. Perspectives on clinical use and content modification There was less consensus when asked about implementation of the tool into routine clinical practice. As shown in Table 2, <50% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that the decision aid would be easy to use in their prac- tice outside of a research setting or that it would be used by most of their colleagues. A slim majority (58%) also believed that implementa- tion would require reorganization of their practice. Respondents mostly agreed or were neutral in their assessment of whether the deci-

- 31. sion aid should be disseminated as an Internet- or DVD-based tool. When asked to identify a preferred time for having their patients review the tool (Table 3), 72% chose prior to initiating the CRC screening discussion, 21% chose after initiating the screening discussion, and 7% chose both. Among the 21 providers who chose the pre-visit approach, 13 preferred that the tool be used in the office just prior to the pre-arranged visit, five preferred at home use and three pre- ferred both; among the six providers who chose the post-visit approach, five preferred in-office use and one preferred at home use. There was also a lack of consensus when asked about content modification. Whereas 50% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that the decision aid should include a discussion of costs, 31% disagreed or strongly disagreed

- 32. Table 2 Provider perspectives on decision aid implementation The decision aid Response category, n (%) Mean item score (SD)* Strongly agree ⁄ agree Neutral Strongly disagree ⁄ disagree 16. Would be easy to use in my practice outside of a research stetting 12 (48) 9 (36) 4 (16) 3.4 ± 1.0 17. Use would require reorganization of my practice for routine clinical use 14 (58) 6 (25) 4 (17) 3.6 ± 1.1 18. Is likely to be used by most of my colleagues 11 (41) 12 (44) 4 (15) 3.4 ± 0.9 19. Should include a discussion of costs 13 (50) 5 (19) 8 (31)

- 33. 3.5 ± 1.2 20. Should be disseminated as an Internet-based tool 17 (63) 8 (30) 2 (7) 3.7 ± 0.9 21. Should be disseminated as a DVD-based tool 15 (56) 8 (30) 4 (15) 3.6 ± 0.9 DVD, digital video disc; SD, standard deviation. *1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree. Table 3 Preferences for clinical use and content modification Item N (%) 22. When would you want your patient to view the decision aid: Before initiating CRC screening discussion (pre-visit) 21 (72) After initiating CRC discussion (post-visit) 6 (21) Both 2 (7) 23. Would you prefer the decision aid to contain information about: All of the recommended screening options 15 (52)

- 34. A more restricted list of options 12 (41) No opinion 2 (7) CRC, colorectal cancer. Colorectal cancer screening decision aid, P C Schroy, S Mylvaganam and P Davidson � 2011 John Wiley & Sons Ltd Health Expectations, 17, pp.27–35 31 (Table 2). Similarly, whereas 52% of providers preferred that the decision aid include a discus- sion of all of the recommended screening options, 41% preferred a more restricted list of options and 7% had no opinion on the issue (Table 3). Only seven providers made suggestions for improving the current decision aid. These included creating non-English versions of the tool (n = 2), clearly distinguishing colonoscopy

- 35. as the best screening option (n = 2), enabling patients to print out their preferred screening option (n = 2), and taking into consideration that patients may not have access to the Internet at home if the decision aid was to be dissemi- nated as a web-based tool (n = 1). There were no complaints. Discussion Decision aids are evidence-based tools that enable patients to make informed, value-con- cordant choices, but the extent to which such tools facilitate SDM from the perspective of the provider is less well established. In an effort to gain new insight into the issue, we conducted a survey of primary care providers participating in a clinical trial evaluating the impact of a novel, DVD-formatted decision aid on SDM and adherence to CRC screening. Our study finds

- 36. that a majority of providers perceived that the tool was a useful, time-saving adjunct to their usual approach to counselling about CRC screening and increased the overall quality of decision making. Moreover, providers also felt that review of the tool just prior to a scheduled office visit was an appropriate use of patient�s time as it enabled the patient to make an informed choice among the different screening options. Together, these findings suggest that much of the tool�s perceived utility was related to its ability to better prepare patients for the screening discussion outside of the clinical encounter and, in so doing, increased both the efficiency and quality of the interaction. Few studies have explored provider perspec- tives on the utility of decision aids for improving SDM. A trial by Green et al. evaluating the effectiveness of genetic counselling vs. counsel-

- 37. ling preceded by use of a computer-based deci- sion aid for breast cancer susceptibility found that although there were no significant differ- ences in perceived effectiveness, use of the tool saved time and shifted the focus away from basic education towards a discussion of personal risk and decision making. 17 A second study by Sim- inoff et al. found that a decision aid for breast cancer adjuvant therapy facilitated a more interactive, informed discussion and helped physicians understand patient preferences. 13 Similarly, Brackett et al. also found that pre- visit use of decision aids for prostate and CRC screening was associated with greater physician satisfaction, as it saved time during the visit and changed the conversation from one of the

- 38. informational exchanges to one of the values and preferences. 18 A fourth study by Graham et al. explored provider perceptions of three decision aids prior to their actual use. 15 Although responses were based on perceptions alone and not on clinical experience, their find- ings were similar to our own. A majority agreed or strongly agreed that the decision aids could meet patients� informational needs about risks and benefits and enable patients to make informed decisions. Similarly, although many felt that the decision aids were likely to com- plement their usual approach, responses were more neutral when asked about the overall impact of the tools on the quality of the patient encounter, patient satisfaction and issues related to implementation. The most striking difference,

- 39. however, was that relatively few of the respon- dents in the study by Graham et al. felt that use of the tool saved time, which could be a reflec- tion of either the complexity of the decisions under consideration and ⁄ or the lack of explicit instructions regarding how the tools were to be used with respect to the timing of the interven- tion and ⁄ or need for provider involvement. Our findings also corroborate a more exten- sive body of literature on barriers to the imple- mentation of decision aids into clinical practice. 14 Even though our study design cir- cumvented many of the barriers related to workflow, accessibility and costs, only 48% of Colorectal cancer screening decision aid, P C Schroy, S Mylvaganam and P Davidson � 2011 John Wiley & Sons Ltd Health Expectations, 17, pp.27–35

- 40. 32 providers felt that actual implementation of the decision aids into their practices outside of the context of a clinical trial would be easy. Based on their feedback, however, most preferred that the tool be used prior to initiating the screening discussion rather than after initiation of the discussion. Moreover, regardless of the timing, a majority preferred that the tool be used in the office rather than at home. Although it is quite possible that their preferences reflected their personal experiences with our study protocol, Brackett et al. also found that pre-visit use was preferred over post-visit use. 18 One of the most commonly cited barriers to implementation of SDM is the time requirement. Although studies to date have provided con-

- 41. flicting data regarding the impact of decision aids on consultation time for other condi- tions, 17–22 we postulated that by educating patients about the risks and benefits of the dif- ferent screening options and facilitating IDM prior to the provider–patient encounter, our decision aid would have the potential of improving the efficiency of SDM and thus save time, as noted by Green et al. and Brackett et al. 17,18 We found that although a majority of providers agreed or strongly agreed that pre-visit use of the tool saved time, 21% were neutral on the issue and 14% disagreed or strongly dis- agreed. It is conceivable that this diversity of opinion might be a reflection of the extent to

- 42. which provider and patient preferences agreed or disagreed. In instances where there was concor- dance between preferences, as was often the case that since colonoscopy was preferred by major- ity of both patients and providers, 16 one would expect that the time required for deliberation and negotiation would be substantially shorter than in situations where there was discordance. Alternatively, these differences might reflect differences in case mix with respect to patient factors, such as literacy level or desired level of participation in the decision-making process. A secondary objective of our study was to elicit provider feedback regarding content and format preferences to gain insight into potential modifications that might enhance future uptake.

- 43. Because of an ongoing debate in the CRC screening literature, 23–27 we focused on content issues related to cost information and number of screening options to include in the decision aid. Both questions elicited a divergence of opinions. Whereas nearly 50% of respondents felt that cost information should be included, the remainder was either neutral or opposed to its inclusion. Similarly, when asked about the number of screening options to include, �50% preferred the full menu of options and �40% preferred a more limited menu. This diversity of opinion highlights some of the key challenges in designing tools with broad dissemination potential. In the light of recent evidence sug- gesting that the number of screening options may influence test choice but not interest in screening and that the importance of out-of-

- 44. pocket costs declines as the number of screening options discussed increases, 26 one approach would be to develop one tool that presents the full menu of screening options without cost information and a second that includes a more limited set of options with cost information. A more appealing approach would be to develop a more comprehensive tool that includes both the full menu of options and cost information in a format that permits navigation so that patients could tailor their use to fit their own informa- tional needs and ⁄ or recommendations of their provider. Internet-based tools are ideally suited for this purpose but, as noted by several par- ticipants in our study, access remains a potential barrier for a sizeable, albeit declining, propor- tion of the target population. Providers in our

- 45. study felt that both Internet- and DVD-for- matted tools were viable options for dissemina- tion, even though the DVD-formatted tool offers less navigation potential. Our study has several notable limitations. First, the survey was conducted among primary care providers at only two institutions, and hence, the findings may not be generalizable to providers in other health care settings. It is noteworthy, however, that the study was con- ducted among a diverse patient population with respect to both race ⁄ ethnicity and educational status. 16 Second, as participating providers never formally reviewed the decision aid, we Colorectal cancer screening decision aid, P C Schroy, S Mylvaganam and P Davidson � 2011 John Wiley & Sons Ltd Health Expectations, 17, pp.27–35

- 46. 33 were unable to assess their opinions with respect to actual content or format. Third, the content of our survey instrument did not allow us to tease out the extent to which use of the decision aid impacted on individual steps of the SDM process. 4,5 Even though satisfaction with the decision-making process was universally high among patients participating in the clinical trial, 16 especially those in the intervention groups, only a relative minority of providers felt that use of the tool helped them tailor their counselling about CRC screening to their patients� needs or increased patient satisfaction

- 47. with their care. Fourth, the anonymous nature of our survey precluded any attempt to correlate response data with exposure rates. It is con- ceivable that the perceptions of providers exposed to multiple patients in the intervention arms might differ from those exposed to only a few patients. Lastly, we cannot rule out the possibility of social response bias, whereby respondents may have felt compelled to offer more positive responses than they actually believed. In conclusion, our study finds that a majority of providers perceived that pre-clinic use of our decision aid for CRC screening was a useful, time-saving adjunct to their usual approach to counselling about CRC screening and increased the overall quality of decision making. Never- theless, many of the providers felt that imple-

- 48. mentation of the decision aid into their practices outside of the context of a clinical trial would be challenging, thus highlighting the need for cost- effective strategies for addressing provider, practice and organizational level barriers to routine use. We speculate that Internet-based tools with enhanced navigation functionality have the greatest dissemination potential, as they offer a feasible, low-cost solution to many of the structural barriers to implementation, as well as a way to reconcile the diversity of opin- ion related to content. Acknowledgement None. Conflicts of interest The authors have no conflict of interests. Funding This study was supported by grant RO1

- 49. HS013912 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. References 1 Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2001. 2 Sheridan SL, Harris RP, Woolf SH. Shared decision making about screening and chemoprevention. A suggested approach from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 2004; 26: 56–66. 3 Briss P, Rimer B, Reilley B et al. Promoting informed decisions about cancer screening in communities and healthcare systems. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 2004; 26: 67–80. 4 Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision- making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Social Science and

- 50. Medicine, 1997; 44: 681–692. 5 Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Decision-making in the physician-patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Social Science and Medicine, 1999; 49: 651–661. 6 Holmes-Rovner M, Valade D, Orlowski C, Draus C, Nabozny-Valerio B, Keiser S. Implementing shared decision-making in routine practice: barriers and opportunities. Health Expectations, 2000; 3: 182–191. 7 Legare F, Ratte S, Gravel K, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision- making in clinical practice: update of a systematic review of health professionals� perceptions. Patient Education and Counseling, 2008; 73: 526–535. 8 Rimer BK, Briss PA, Zeller PK, Chan EC, Woolf SH. Informed decision making: what is its role in cancer screening? Cancer, 2004; 101: 1214–1228. 9 International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration. IPDAS Collaboration

- 51. Background Document, 2005. Available at: http:// ipdas.ohri.ca/IPDAS_Background.pdf, accessed 26 October 2010. 10 Elwyn G, O�Connor A, Stacey D et al. Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: online international Delphi consensus process. BMJ, 2006; 333: 417. Colorectal cancer screening decision aid, P C Schroy, S Mylvaganam and P Davidson � 2011 John Wiley & Sons Ltd Health Expectations, 17, pp.27–35 34 11 O�Connor AM, Bennett CL, Stacey D et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2009; 3: CD001431. 12 O�Connor AM, Llewellyn-Thomas HA, Sawka C, Pinfold SP, To T, Harrison DE. Physicians� opinions about decision aids for patients considering systemic adjuvant therapy for axillary-node negative breast

- 52. cancer. Patient Education and Counseling, 1997; 30: 143–153. 13 Siminoff LA, Gordon NH, Silverman P, Budd T, Ravdin PM. A decision aid to assist in adjuvant therapy choices for breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 2006; 15: 1001–1013. 14 O�Donnell S, Cranney A, Jacobsen MJ, Graham ID, O�Connor AM, Tugwell P. Understanding and over- coming the barriers of implementing patient decision aids in clinical practice. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 2006; 12: 174–181. 15 Graham ID, Logan J, Bennett CL et al. Physicians� intentions and use of three patient decision aids. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 2007; 7: 20. 16 Schroy PC III, Emmons K, Peters E et al. The impact of a novel computer-based decision aid on shared decision making for colorectal cancer screening: a randomized trial. Medical Decision Making, 2011; 31:

- 53. 93–107. 17 Green MJ, Peterson SK, Baker MW et al. Use of an educational computer program before genetic coun- seling for breast cancer susceptibility: effects on duration and content of counseling sessions. Genetics in Medicine, 2005; 7: 221–229. 18 Brackett C, Kearing S, Cochran N, Tosteson AN, Blair Brooks W. Strategies for distributing cancer screening decision aids in primary care. Patient Education and Counseling, 2010; 78: 166–168. 19 Whelan T, Sawka C, Levine M et al. Helping patients make informed choices: a randomized trial of a decision aid for adjuvant chemotherapy in lymph node-negative breast cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 2003; 95: 581–587. 20 Bekker HL, Hewison J, Thornton JG. Applying decision analysis to facilitate informed decision making about prenatal diagnosis for Down syn-

- 54. drome: a randomised controlled trial. Prenatal Diag- nosis, 2004; 24: 265–275. 21 Butow P, Devine R, Boyer M, Pendlebury S, Jackson M, Tattersall MH. Cancer consultation preparation package: changing patients but not physicians is not enough. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2004; 22: 4401– 4409. 22 Nannenga MR, Montori VM, Weymiller AJ et al. A treatment decision aid may increase patient trust in the diabetes specialist. The Statin Choice randomized trial. Health Expectations, 2009; 12: 38–44. 23 Leard LE, Savides TJ, Ganiats TG. Patient prefer- ences for colorectal cancer screening. Journal of Family Practice, 1997; 45: 211–218. 24 Pignone M, Bucholtz D, Harris R. Patient preferences for colon cancer screening. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 1999; 14: 432–437. 25 Lafata JE, Divine G, Moon C, Williams LK. Patient-

- 55. physician colorectal cancer screening discussions and screening use. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 2006; 31: 202–209. 26 Griffith JM, Lewis CL, Brenner AR, Pignone MP. The effect of offering different numbers of colorectal cancer screening test options in a decision aid: a pilot randomized trial. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision-Making, 2008; 8: 4. 27 Jones RM, Vernon SW, Woolf S. Is discussion of colorectal cancer screening options associated with heightened patient confusion? Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention, 2010; 19: 2821–2825. Colorectal cancer screening decision aid, P C Schroy, S Mylvaganam and P Davidson � 2011 John Wiley & Sons Ltd Health Expectations, 17, pp.27–35 35

- 56. Copyright of Health Expectations is the property of Wiley- Blackwell and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use. Copyright of Health Expectations is the property of Wiley- Blackwell and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use. Shared Decision-Making in Intensive Care Units Executive Summary of the American College of Critical Care Medicine and American Thoracic Society Policy Statement Shared decision-making is a central component of patient- centered care in the intensive care unit (ICU) (1–4); however, there remains confusion about what shared decision-making is and when shared decision-making ought to be used. Further, failure to employ appropriate decision-making techniques can lead to significant problems. For example, if clinicians leave decisions largely to the discretion of surrogates without providing adequate

- 57. support, surrogates may struggle to make patient-centered decisions and may experience psychological distress (5). Conversely, if clinicians make treatment decisions without attempting to understand the patient’s values, goals, and preferences, decisions will likely be predominantly based on the clinicians’ values, rather than the patient’s, and patients or surrogates may feel they have been unfairly excluded from decision-making (1, 2). Finding the right balance is therefore essential. To clarify these issues and provide guidance, the American College of Critical Care Medicine (ACCM) and American Thoracic Society (ATS) recently released a policy statement that provides a definition of shared decision-making in the ICU environment, clarification regarding the range of appropriate models for decision-making in the ICU, a set of skills to help clinicians create genuine partnerships in decision- making with patients/surrogates, and ethical analysis supporting the findings (6). To develop a unified policy statement, the Ethics Committee of the ACCM and the Ethics and Conflict of Interest Committee of the ATS convened a writing group composed of members of these committees. The writing group reviewed pertinent literature published in a broad array of journals, including those with a focus in medicine, surgery, critical care, pediatrics, and bioethics, and discussed findings with the full ACCM and ATS ethics committees throughout the writing process. Recommendations were generated after review of empirical research and normative analyses published in peer-reviewed journals. The policy statement was reviewed, edited, and approved by consensus of the full Ethics Committee

- 58. of the ACCM and the full Ethics and Conflict of Interest Committee of the ATS. The statement was subsequently reviewed and approved by the ATS, ACCM, and Society of Critical Care Medicine leadership, through the organizations’ standard review and approval processes. ACCM and ATS endorse the following definition: Shared decision-making is a collaborative process that allows patients, or their surrogates, and clinicians to make health care decisions together, taking into account the best scientific evidence available, as well as the patient’s values, goals, and preferences. Clinicians and patients/surrogates should use a shared decision-making process to define overall goals of care (including decisions regarding limiting or withdrawing life-prolonging interventions) and when making major treatment decisions that may be affected by personal values, goals, and preferences (7, 8). Once clinicians and the patient/surrogate agree on general goals of care, clinicians confront many routine decisions (e.g., choice of vasoactive drips and rates, laboratory testing, fluid rate). It is logistically impractical to involve patients/surrogates in each of these decisions. Partnerships in decision-making require that the overall goals of care and major preference-sensitive decisions be made using a shared decision-making approach. The clinician then has a fiduciary responsibility to use experience and evidence-

- 59. based practice when making day-to-day treatment decisions that are consistent with the patient’s values, goals, and preferences. Throughout the ICU stay, important, preference-sensitive choices often arise. When they do, clinicians should employ shared decision-making. Clinicians should generally start with a default shared decision- making approach that includes the following three main elements: information exchange, deliberation, and making a treatment decision. This model should be considered the default approach to shared decision-making, and should be modified according to the needs and preferences of the patient/surrogate. Using such a model, the patient or surrogate shares information about the patient’s values, goals, and preferences that are relevant to the decision at hand. Clinicians share information about the relevant treatment options and their risks and benefits, including the option of palliative care without life-prolonging interventions. Clinicians and the patient/surrogate then deliberate together to determine which option is most appropriate for the patient, and together they agree on a care plan. In such a model, the authority and burden of decision-making is shared relatively equally (9). Although data suggest that a preponderance of patients/surrogates prefer to share responsibility for decision-making relatively equally with clinicians, many patients/surrogates prefer to exercise greater authority in

- 60. decision-making, and many other patients/surrogates prefer to defer even highly value-laden choices to clinicians (10–13). Ethically justifiable models of decision-making include a broad range to accommodate such differences in needs and preferences. In some cases, the patient/surrogate may wish to exercise significant authority in decision-making. In such cases, the clinician should understand the patient’s values, goals, and preferences to a sufficient degree to ensure the medical decisions are congruent with these values. The clinician then determines and presents the range of medically appropriate options, and the patient/surrogate chooses from among these options. In such a model, the patient/surrogate bears the majority of the responsibility and burden of decision-making. In cases in which the patient/surrogate demands interventions the clinician believes are potentially inappropriate, clinicians should follow the recommendations presented in the recently published multiorganization policy statement on this topic (14). In other cases, the patient/surrogate may prefer that clinicians bear the primary burden in making even difficult, value-laden choices. Research suggests that nearly half of surrogates of critically ill patients prefer that physicians independently make some types of treatment decisions (10–13). Further, data suggest that approximately 5–20% of surrogates of ICU patients want clinicians to make highly value-laden choices, including decisions to limit or

- 61. 1334 American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine Volume 193 Number 12 | June 15 2016 EDITORIALS withdraw life-prolonging interventions (12, 13). In such cases, using a clinician-directed decision-making model is ethically justifiable (15–24). Employing a clinician-directed decision-making model requires great care. The clinician should ensure that the surrogate’s preference for such a model is not based on inadequate information, insufficient support from clinicians, or other remediable causes. Further, when the surrogate prefers to defer a specific decision to the clinician, the clinician should not assume that all subsequent decisions are also deferred. The surrogate should therefore understand what specific choice is at hand and should be given as much (or as little) information as the surrogate wishes. Under such a model, the surrogate cedes decision- making authority to the clinician and does not need to explicitly agree to (and thereby take responsibility for) the decision that is made. The clinician should explain not only what decision the clinician is making but also the rationale for the decision, and must then explicitly give the surrogate the opportunity to disagree. If the surrogate does not disagree, it is reasonable to implement the care decision (19–24). Readers may review references 19–24 for

- 62. detailed descriptions and ethical analyses of clinician-directed decision- making. The statement was intended for use in all ICU environments. Patients and surrogate decision-makers have similar rights both to participate in decision-making when appropriate and to rely more heavily on providers when they wish to do so, regardless of the type of ICU. Similarly, the statement is equally applicable in pediatric and neonatal settings, where decision-making partnerships between parents and the ICU team are equally important. As noted in the statement, including children in some decisions can often be appropriate as well. The statement is also intended to be applicable internationally. Although patient and surrogate decision-making preferences may differ globally, the default approach presented and the recommendation to adjust the decision-making model to fit the preferences of the patient or surrogate are universal. Both ACCM and ATS are international organizations, and the literature review included publications from many countries. The statement focuses on the ICU environment because critically ill patients are often, but not always, unable to participate in decision-making themselves, and because many decisions in the ICU are value- sensitive. The recommendations in the statement, however, could be equally applicable in all patient care settings. To optimize shared decision-making, clinicians should be trained in specific communication skills. Core categories of

- 63. skills include establishing a trusting relationship with the patient/surrogate; providing emotional support; assessing patients’/surrogates’ understanding of the situation; explaining the patient’s condition and prognosis; highlighting that there are options to choose from; explaining principles of surrogate decision-making; explaining treatment options; eliciting patient’s values, goals, and preferences; deliberating together; and making a decision. The full policy statement provides significant guidance and examples in these areas (6). Finally, ACCM and ATS recommend further research to assess the use of various approaches to decision-making in the ICU. The use of decision aids, communication skills training, implementation of patient navigator or decision support counselor programs, and other interventions should be subjected to randomized controlled trials to assess efficacy. Considerations regarding the cost and time burdens should be weighed against anticipated benefits from such interventions when determining which efforts to implement. n Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org. Acknowledgment: The views expressed in this article represent the official position of the American College of Critical Care Medicine, the Society of Critical Care Medicine, and the American Thoracic Society. These views do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Department

- 64. of the Navy, U.S. Department of Defense, U.S. National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, or U.S. Government. Alexander A. Kon, M.D. Naval Medical Center San Diego San Diego, California and University of California San Diego San Diego, California Judy E. Davidson, D.N.P., R.N. University of California Health System San Diego, California Wynne Morrison, M.D. Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Marion Danis, M.D. National Institutes of Health Bethesda, Maryland Douglas B. White, M.D., M.A.S. University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania References 1. Carlet J, Thijs LG, Antonelli M, Cassell J, Cox P, Hill N, Hinds C, Pimentel JM, Reinhart K, Thompson BT. Challenges in end-of-life care in

- 65. the ICU: statement of the 5th International Consensus Conference in Critical Care: Brussels, Belgium, April 2003. Intensive Care Med 2004;30:770–784. 2. Thompson BT, Cox PN, Antonelli M, Carlet JM, Cassell J, Hill NS, Hinds CJ, Pimentel JM, Reinhart K, Thijs LG; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society; European Society of Intensive Care Medicine; Society of Critical Care Medicine; Sociètède Rèanimation de Langue Française. Challenges in end-of-life care in the ICU: statement of the 5th International Consensus Conference in Critical Care: Brussels, Belgium, April 2003: executive summary. Crit Care Med 2004;32:1781–1784. 3. Davidson JE, Powers K, Hedayat KM, Tieszen M, Kon AA, Shepard E, Spuhler V, Todres ID, Levy M, Barr J, et al.; American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004-2005, Society of Critical Care Medicine. Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004-2005. Crit Care Med 2007;35:605– 622. 4. Lanken PN, Terry PB, Delisser HM, Fahy BF, Hansen- Flaschen J,

- 66. Heffner JE, Levy M, Mularski RA, Osborne ML, Prendergast TJ, et al.; ATS End-of-Life Care Task Force. An official American Thoracic Society clinical policy statement: palliative care for patients with respiratory diseases and critical illnesses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;177:912–927. 5. Gries CJ, Engelberg RA, Kross EK, Zatzick D, Nielsen EL, Downey L, Curtis JR. Predictors of symptoms of posttraumatic stress and depression in family members after patient death in the ICU. Chest 2010;137:280–287. Editorials 1335 EDITORIALS http://www.atsjournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1164/rccm.201602- 0269ED/suppl_file/disclosures.pdf http://www.atsjournals.org 6. Kon AA, Davidson JE, Morrison W, Danis M, White DB; American College of Critical Care Medicine; American Thoracic Society. Shared decision making in ICUs: an American College of Critical Care Medicine and American Thoracic Society policy statement. Crit Care Med 2016;44:188–201. 7. O’Connor AM, Llewellyn-Thomas HA, Flood AB. Modifying

- 67. unwarranted variations in health care: shared decision making using patient decision aids. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;Suppl Variation: VAR63-72. 8. O’Connor AM, Wennberg JE, Legare F, Llewellyn-Thomas HA, Moulton BW, Sepucha KR, Sodano AG, King JS. Toward the ‘tipping point’: decision aids and informed patient choice. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007; 26:716–725. 9. Charles C, Whelan T, Gafni A. What do we mean by partnership in making decisions about treatment? BMJ 1999;319:780–782. 10. Heyland DK, Cook DJ, Rocker GM, Dodek PM, Kutsogiannis DJ, Peters S, Tranmer JE, O’Callaghan CJ. Decision-making in the ICU: perspectives of the substitute decision-maker. Intensive Care Med 2003;29:75–82. 11. Anderson WG, Arnold RM, Angus DC, Bryce CL. Passive decision- making preference is associated with anxiety and depression in relatives of patients in the intensive care unit. J Crit Care 2009;24: 249–254. 12. Johnson SK, Bautista CA, Hong SY, Weissfeld L, White DB. An empirical study of surrogates’ preferred level of control over value-

- 68. laden life support decisions in intensive care units. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;183:915–921. 13. Madrigal VN, Carroll KW, Hexem KR, Faerber JA, Morrison WE, Feudtner C. Parental decision-making preferences in the pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2012;40:2876–2882. 14. Bosslet GT, Pope TM, Rubenfeld GD, Lo B, Truog RD, Rushton CH, Curtis JR, Ford DW, Osborne M, Misak C, et al.; American Thoracic Society ad hoc Committee on Futile and Potentially Inappropriate Treatment; American Thoracic Society; American Association for Critical Care Nurses; American College of Chest Physicians; European Society for Intensive Care Medicine; Society of Critical Care. An Official ATS/AACN/ACCP/ESICM/SCCM policy statement: responding to requests for potentially inappropriate treatments in intensive care units. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;191: 1318–1330. 15. Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of biomedical ethics, 5th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. 16. Loewy EH, Loewy RS. Textbook of healthcare ethics, 2nd ed. Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2004.

- 69. 17. Lo B. Resolving ethical dilemmas, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000. 18. Thompson DR, Kaufman D, editors. Critical care ethics: a practice guide, 3rd ed. Mount Prospect, IL: Society of Critical Care Medicine; 2014. 19. Curtis JR, Burt RA. Point: the ethics of unilateral “do not resuscitate” orders: the role of “informed assent”. Chest 2007;132:748–751. 20. Kon AA. Informed nondissent rather than informed assent. Chest 2008; 133:320–321. 21. Kon AA. The “window of opportunity:” helping parents make the most difficult decision they will ever face using an informed non- dissent model. Am J Bioeth 2009;9:55–56. 22. Kon AA. The shared decision-making continuum. JAMA 2010;304: 903–904. 23. Kon AA. Informed non-dissent: a better option than slow codes when families cannot bear to say “let her die.” Am J Bioeth 2011;11:22–23. 24. Curtis JR. The use of informed assent in withholding cardiopulmonary

- 70. resuscitation in the ICU. Virtual Mentor 2012;14:545–550. Copyright © 2016 by the American Thoracic Society 1336 American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine Volume 193 Number 12 | June 15 2016 EDITORIALS