Centre for Child Law Heads of Argument Child Identiity Case

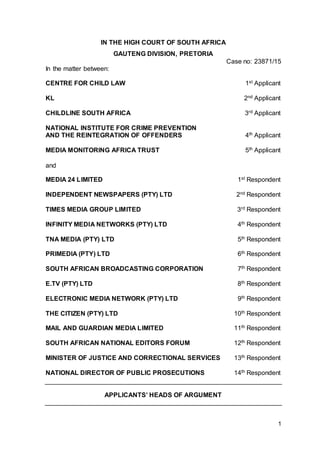

- 1. 1 IN THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA GAUTENG DIVISION, PRETORIA Case no: 23871/15 In the matter between: CENTRE FOR CHILD LAW 1st Applicant KL 2nd Applicant CHILDLINE SOUTH AFRICA 3rd Applicant NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR CRIME PREVENTION AND THE REINTEGRATION OF OFFENDERS 4th Applicant MEDIA MONITORING AFRICA TRUST 5th Applicant and MEDIA 24 LIMITED 1st Respondent INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPERS (PTY) LTD 2nd Respondent TIMES MEDIA GROUP LIMITED 3rd Respondent INFINITY MEDIA NETWORKS (PTY) LTD 4th Respondent TNA MEDIA (PTY) LTD 5th Respondent PRIMEDIA (PTY) LTD 6th Respondent SOUTH AFRICAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION 7th Respondent E.TV (PTY) LTD 8th Respondent ELECTRONIC MEDIA NETWORK (PTY) LTD 9th Respondent THE CITIZEN (PTY) LTD 10th Respondent MAIL AND GUARDIAN MEDIA LIMITED 11th Respondent SOUTH AFRICAN NATIONAL EDITORS FORUM 12th Respondent MINISTER OF JUSTICE AND CORRECTIONAL SERVICES 13th Respondent NATIONAL DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC PROSECUTIONS 14th Respondent APPLICANTS’ HEADS OF ARGUMENT

- 2. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS OVERVIEW..........................................................................................................................3 The applicants and their approach...................................................................................4 The attitude of the respondents ........................................................................................7 Preliminary observations....................................................................................................8 Structure of these submissions...................................................................................... 10 PART 1: LEGAL AND FACTUAL BACKGROUND.................................................. 11 Legislative framework...................................................................................................... 11 The evidence of the individuals affected ...................................................................... 13 Expert evidence on the harms of identification ........................................................... 27 PART 2: THE RIGHTS AT STAKE .............................................................................. 39 The best interests of the child ........................................................................................ 39 Privacy and dignity........................................................................................................... 44 Equality.............................................................................................................................. 47 Fair trial rights ................................................................................................................... 48 Freedom of expression and open justice ..................................................................... 48 PART 3: PROTECTION FOR CHILD VICTIMS OF CRIME..................................... 57 The need to protect child victims’ anonymity............................................................... 57 Properly interpreted, section 154(3) protects child victims........................................ 75 Alternatively, section 154(3) is unconstitutional .......................................................... 83 PART 4: PROTECTION FOR CHILD VICTIMS, WITNESSES, ACCUSED AND OFFENDERS AFTER 18................................................................................................ 99 The need for ongoing protection in adulthood............................................................. 99 Properly interpreted, section 154(3) confers ongoing protection ...........................114 Alternatively, section 154(3) is unconstitutional ........................................................118 CONCLUSION ...............................................................................................................124

- 3. 3 OVERVIEW 1 Children who are victims, witnesses, or perpetrators of crime are in an acutely vulnerable position. If their identities are revealed in the media or in other public forums, they face severe and life-long harms. 2 For this reason, section 154(3) of the Criminal Procedure Act 51 of 1977 (“the CPA”) protects the anonymity of children in the criminal justice system. It provides that: “No person shall publish in any manner whatever any information which reveals or may reveal the identity of an accused under the age of eighteen years or of a witness at criminal proceedings who is under the age of eighteen years: Provided that the presiding judge or judicial officer may authorize the publication of so much of such information as he may deem fit if the publication thereof would in his opinion be just and equitable and in the interest of any particular person.” 3 Section 154(3) of the CPA makes anonymity the default position for children. These protections may only be lifted with the permission of a court, provided that it is just and equitable to do so. 4 It concerns the scope and duration of the anonymity protections afforded by section 154(3) of the CPA. It raises two primary issues. 4.1 First, does section 154(3) truly exclude child victims from its protection as members of the media contend, while providing automatic protection to children who are accused of crimes or are witnesses? If so, is this consistent with the Constitution?

- 4. 4 4.2 Second, do children who are protected under section 154(3) of the CPA lose all protection as soon as they turn 18, again as members of the media contend? If so, is this consistent with the Constitution? The applicants and their approach 5 These heads of argument deal only with Part B of this application. In Part A, the applicants obtained an interim interdict to protect the anonymity of the second applicant, KL, pending the finalisation of Part B.1 5.1 KL is known to the media and public as “Zephany Nurse”, although she uses a different name. 5.2 In February 2015, KL discovered that she had been abducted as a baby from Groote Schuur hospital. At this time, KL was 17 years old and in her matric year. 5.3 In the ensuing media frenzy, there were constant threats that KL’s identity would be revealed. This risk increased as her 18th birthday approached, as many members of the media appeared to believe that they would be free to identify her after she turned 18.2 5.4 The interdict obtained in Part A protects KL’s anonymity pending the finalisation of this application. 1 Order of Bertelsmann J on 21 April 2015; Supplementary founding affidavit (“SFA”), Annexure AMS 24, pp 259 – 261. 2 FA, pp 33 – 43, paras 52 – 76.

- 5. 5 6 KL’s case highlights the important need for clarity on the scope and duration of the protection afforded by section 154(3) of the CPA. 6.1 As a victim of crime who had at that stage not yet testified at trial, there was uncertainty whether section 154(3) protected KL’s anonymity at all. 6.2 Furthermore, some members of the media took the position that any protection afforded to KL under section 154(3) of the CPA would automatically terminate on her 18th birthday.3 7 KL is, however, not alone. As the evidence makes clear, other child victims also face the risk of being identified in the media as a result of the current lack of clarity over the application of section 154(3) of the CPA to child victims. Furthermore, all children who are subject to the protection of section 154(3) face the risk of having their identities revealed as soon as they turn 18. 8 For these reasons, the relief sought in Part B is essential to ensure ongoing protection for KL and other child victims, witnesses, accused and offenders. 9 This is why the application is brought not merely by KL herself, but also by four highly respected NGOs specialising in this area – the Centre for Child Law, ChildLine, NICRO and Media Monitoring Africa. 10 In respect of the first issue identified in paragraph 4 above, the applicants contend that child victims of crime are not and cannot be excluded from the 3 FA, p 41, para 74. See in particular Annexure AMS 17, p 151.

- 6. 6 protections of section 154(3) of the CPA merely because they do not testify at trial. They therefore seek: 10.1 An order declaring that, on a proper interpretation, the protections afforded by section 154(3) of the CPA apply to victims of crime who are younger than 18 years of age.4 10.2 In the alternative, an order declaring section 154(3) of the CPA unconstitutional and invalid to the extent that it fails to confer its protection on victims under 18, as well an order to remedy the defect.5 11 In respect of the second issue identified in paragraph 4 above, the applicants contend that children who are subject to section 154(3) do not and cannot lose all protection when they turn 18. They therefore seek: 11.1 An order declaring that, on a proper interpretation of the provision, child victims, witnesses, accused and offenders do not forfeit the protections of section 154(3) when they reach the age of 18.6 11.2 In the alternative, an order declaring section 154(3) of the CPA unconstitutional and invalid to the extent that children subject to it forfeit the protections of section 154(3) when they reach the age of 18, as well an order to remedy the defect.7 4 Notice of Motion, Part B, prayer 1; Record, p 4. 5 Ibid, prayer 2; Record, p 4 – 5. 6 Ibid, prayer 3; Record, p 5. 7 Ibid, prayer 4; Record, p 5.

- 7. 7 The attitude of the respondents 12 The Minister for Justice and Correctional Services (“the Minister”) is responsible for the administration of the CPA. The Minister does not oppose any part of this application. 12.1 The Minister agrees with the applicants that, on a proper interpretation, section 154(3) protects the anonymity of child victims of crime and that children who are subject to its protection do not forfeit this protection when they turn 18.8 12.2 Even in respect of the alternative constitutional challenges, the Minister does not oppose these and instead abides them.9 13 Accordingly, the only parties opposing the relief sought in this application are the first to third respondents (“the media respondents”), owners of some of the largest and most powerful media organisations in South Africa.10 13.1 The media respondents take the position that section 154(3) of the CPA does not protect the anonymity of children who are victims of crime, such as KL. 13.2 They further contend that children who are protected by section 154(3) of the CPA automatically lose all protection as soon as they turn 18. 8 Minister’s Answering Affidavit (“Minister’s AA”), pp 781 – 788, paras 3, 5. 9 Ibid, paras 4, 6. 10 See FA, p 16 – 18, paras 11 – 13 for a list of publications owned by the media respondents.

- 8. 8 Preliminary observations 14 There are two preliminary observations that are of importance. 15 First, the approach urged by the applicants is not an attempt to prevent all media reporting of crimes involving child victims or child offenders. 15.1 Even once the applicants’ arguments are upheld, section 154(3) does not prevent the media from reporting on the trial or from attending court. Subject to other statutory restrictions11 not at issue in this application, the media remain at liberty to report on all matters arising from the trial, save those details that reveal or may reveal the identity of children involved in these proceedings. 15.2 The prohibition is also not absolute or permanent. It expressly empowers courts, upon application, to permit the publication of identifying information provided this is “just and equitable and in the interests of any particular person”. 15.3 This is necessary to ensure that it is the courts – rather than the media houses themselves – retain the final decision on whether to allow the publication of identifying information in given cases. This ensures that the best interests of the child will not be compromised. 15.4 It is also necessary to ensure that if any party has to approach the courts regarding whether publication of identifying information is to be allowed 11 Particularly section 63(5) of the Child Justice Act 75 of 2008.

- 9. 9 in a specific case, it is the media that must do so. The suggestion by the media respondents that this burden to approach the courts should fall instead on the vulnerable children themselves is simply not sustainable, as we demonstrate in what follows. 16 Second, it is significant that some of the publications owned by the media respondents have shown little regard for children’s rights in their reporting. 16.1 As is evident in the examples presented in this application, these publications have consistently revealed the identities of child victims and have also revealed the identities of offenders after they turn 18.12 16.2 By their own admission, these publications have done so in the belief that stories that reveal the identities of children are more lucrative than those that do not.13 16.3 In short, the media respondents have made a business out of disregarding the best interests and privacy rights of some of the most vulnerable children. Their oppositionto this application is, in large part, an attempt to preserve those commercial interests. 16.4 As we demonstrate in these heads of argument, the media respondents’ position is untenable. Their position fails to strike an appropriate balance between the rights of vulnerable children and 12 See, for example,coverage of KL: AMS 42 – 46, pp 929 - 937; coverage of MVB: Annexures LB 1 -2, 7, 10- 11, pp 884 – 898, 912 – 915, 922 – 924; coverage of PN: Annexures WRB 5 – 6, pp 431 – 447; coverage of DS: Annexure DS 1, pp 274 – 275;AMS 29 – 30, pp 314 – 323; coverage of MO: AMS 31, pp 324 – 325. See also, the media coverage on child victims of gang violence, Annexure SS 7 – 8, pp 586 – 606. 13 Media Respondents’ Answering Affidavit (“AA”), pp 507 – 508, paras 88 – 90.

- 10. 10 countervailing interests because it largely disregards the interests of children. Structure of these submissions 17 In what follows, we deal with the issues that arise in this application in four parts. 17.1 In Part 1, we address the legal and factual background to this application, including the extensive expert evidence on the harms of identification in the media and other public forums. 17.2 In Part 2, we set out the constitutional rights at stake and the relevant legal principles. 17.3 In Part 3, we explain why section 154(3) of the CPA must be interpreted to protect children who are victims of crime or, alternatively, must be declared unconstitutional. 17.4 In Part 4, we explain why section 154(3) of the CPA must be interpreted to protect child victims, witnesses, accused and offenders after they turn 18 or, alternatively, must be declared unconstitutional.

- 11. 11 PART 1: LEGAL AND FACTUAL BACKGROUND 18 In this part, we address three issues: 18.1 We begin by outlining section 154(3) of the CPA in the context of the broader legislative framework. 18.2 We then deal with the evidence regarding the experiences of KL and other children who have been identified in the media or face the threat of being identified. 18.3 Third, we summarise the expert evidence on the harms of identification in the media and other public forums. Legislative Framework 19 Section 154(3) of the CPA establishes the default position that the publication of information that reveals or may reveal the identities of the children concerned is prohibited. 20 As we have indicated, the prohibition is also not absolute or permanent. It expressly empowers courts, upon application, to permit the publication of identifying information provided this is “just and equitable and in the interests of any particular person”. 21 Two categories of children are expressly protected by section 154(3): 21.1 “[A]n accused under the age of 18 years”; and

- 12. 12 21.2 “[A] witness at criminal proceedings who is under the age of eighteen years” “An accused under the age of 18 years” 22 With regard to “an accused under the age of 18 years”, section 154(3) has to be considered together with the broader framework of the Child Justice Act 75 of 2008 (“CJA”). 23 Under the CJA, all children accused of committing crimes must be tried in child justice courts in accordance with the procedures set out in that Act, and any court before which an accused child appears is a child justice court. Section 63(6) of the CJA makes section 154(3) of the CPA applicable to these proceedings — “Section 154(3) of the Criminal Procedure Act applies with the changes required by the context regarding the publication of information.” 24 Accordingly, where we refer to section 154(3) of the CPA, this must be understood as including a reference, where applicable, to section 63(6) of the CJA. “A child witness at criminal proceedings” 25 Section 154(3) of the CPA also protects the identity of a “witness at criminal proceedings” who is under the age of 18. This is irrespective of the type of offence alleged to have been committed. The provision applies even if the child concerned is not a complainant and where the child merely witnessed the crime concerned.

- 13. 13 26 The provision does not expressly indicate that it covers child victims who are not called as witnesses. Nevertheless, as we argue below, all child victims are potential witnesses who may be called to testify. As a result, this provision must be interpreted expansively to provide protection to child victims. 27 We note that sections 153 and 154 of the CPA also contain other provisions dealing with possible anonymity for those involved in criminal trials. However, as we explain below, these provisions do not provide adequate protection to the child victims, witnesses and offenders at issue in these proceedings. The evidence of the individuals affected 28 As indicated above, this case arises from the difficulties experienced by KL in attempting to protect her anonymity before and after her 18th birthday.14 29 However, the relief sought in this application has far broader application. It concerns the rights of all children who are victims, witnesses or perpetrators of crime to be protected from being identified under section 154(3) of the CPA.15 30 The applicants have put up evidence from children and young adults who were victims, witnesses or perpetrators of crime during their childhood. They all suffered the harm of being identified in the media or, like KL, are at great risk of being identified. In what follows, we briefly summarise their experiences. 14 Founding affidavit (“FA”), p 25, paras 26 and p 33, para 52. 15 Ibid, p25, para 27.

- 14. 14 The case of KL 31 KL was “discovered” in February 2015 after her biological sister was enrolled at the same high school. The distinct similarity between KL and her sister caused KL’s biological father to conduct his own investigations. 32 DNA tests were conducted which confirmed that KL was “Zephany Nurse" the baby who had been stolen at birth from Groote Schuur Hospital. This discovery led to the arrest of the person KL had known as her mother all her life.16 33 Following KL’s “discovery”, there was intense media interest in her case. Journalists set up camp outside KL’s house and school in an attempt to take pictures of her and report on her story. 34 KL was taken to a place of safety, in large part because of this intense media scrutiny.17 35 At the time of her discovery, KL was 17 years of age.18 Media reports contained suggestions that the media was prohibited from publishing any information regarding KL’s identity but that the prohibition would fall away when she turned 18 at the end of April 2015.19 16 Ibid, p33, para 53-54. 17 Ibid, p 34, para 54-57. 18 Ibid, p 26, para 33. 19 Ibid, p 27, paras 34.1-35.

- 15. 15 36 As a result, KL was living in fear of being identified in the media as this would destroy her chances of a normal life.20 37 The Centre for Child Law addressed correspondence to the various media houses requesting an undertaking that they would not reveal KL’s identity. None of the media houses provided the undertaking as requested. Lawyers acting for YOU Magazine and Huisgenoot expressly stated that the statutory protection would lapse on KL turning 18 and the media would be permitted to reveal KL’s identity.21 38 Despite obtaining an interim court order in these proceedings to protect her anonymity,22 KL has still faced constant threats of being identified: 38.1 In July 2015, KL’slegal representative discovered by chance that a book on KL was due to be published, with picture of KL on its front cover. A small black strip was placed across KL’s face, but she would have been easily identifiable by anyone that had met her. The publishers were eventually persuaded to change the cover only after the threat of legal action.23 38.2 In March 2016, the Daily Voice, owned by the second respondent, published a series of articles including photographs of KL in which her face was partially obscured by pixellation. KL’s legal representatives 20 KL’s affidavit, Annexure AMS 1, pp 63-64, paras 20 – 24. 21 FA, p 34 -37, para 57-63. 22 SFA, p 259, Annexure AMS 24. 23 Reply, pp 805 – 807, para 34.5; Annexure AMS 40 – 41, pp 925 – 927.

- 16. 16 brought a complaint to the Press Ombudsman, who held that the articles breached the court order and the Press Code. While KL succeeded, the ruling brought her no direct relief apart from an apology.24 38.3 In June 2016, YOU Magazine (published by the first respondent) carried a story in which it included pictures of KL’s biological sister, despite the fact that it had been reported that KL and her sister look very similar, a fact that was repeated in the YOU article.25 38.4 In August 2016, the New Age newspaper (published by the sixth respondent) carried a story on its website reporting that KL was pregnant. The article indicated that this had been confirmed by KL’s aunt and referred to the aunt by name.26 A number of other publications picked up and reported on the New Age story27 and at least two also included the name of KL’s aunt in their articles.28 39 This shows that KL remains at great risk of being identified by the media. 39.1 KL has explained the intense fear that if she is identified then she will not be able to make a normal life for herself.29 39.2 The potential harms to KL have also been analysed in great detail in the expert report of Dr Giada Del Fabbro and this assessment is confirmed 24 Reply, pp 812 – 813, para 43.2.; Annexure AMS 46, pp 934 – 937. 25 Reply, p 812, para 43.1. 26 Supplementary affidavit, pp 972-3, para 8; Annexure SA3, pp 982-984. 27 Annexure SA8, pp 993-4 28 Annexure SA9, p 995 and Annexure SA12, p 1001-2. 29 KL’s affidavit, pp 62 – 64, paras 18 – 24.

- 17. 17 by Ms Lena Goosen, the social worker who has worked most closely with KL.30 39.3 In this light, it is clear that KL is in urgent need of the relief sought in Part B in order to give her permanent protection. The case of MVB 40 KL has been relatively fortunate, in that her identity has not yet been fully disclosed in the media. This is in contrast with MVB, another child victim of crime who continues to be identified in the media without her consent, despite a court order expressly prohibiting this. 41 MVB is a survivor of a horrific attack. Her family was murdered by an axe- wielding assailant in their home, leaving with severe injuries. 42 The media respondents seek to use MVB’s as an example that identification in the media is beneficial for the victims and their families at large.31 The media respondents incorrectly assume that their invasion of MVB’s privacy has assisted her healing process.32 42.1 MVB’s court-appointed curator, Advocate Louise Buikman SC, provides a direct rebuttal to these claims. 30 Dr Del Fabbro’s report, pp 382 – 383; Affidavit by Ms Goosen, pp 945 – 949. 31 Answering affidavit, p483 para 52. 32 AA, pp 483,486, 502, paras 52, 53.3, 81.

- 18. 18 42.2 In her supporting affidavit, Advocate Buikman SC explains that MVB has endured great stress and potential danger due to the media’s continued interference in her life.33 42.3 Advocate Buikman SC further endorses the relief sought in this application as a means to protect MVB and to ensure that other children do not endure the same trauma that she has experienced.34 43 Shortly after the commission of the crime, the media published details of MVB’s school, her name, photographs, and details of institutions she was receiving treatment. This was without her consent, as she was in a coma at the time.35 44 On her release from hospital, the media continued to follow her and to publish intimate details about her life. This included paparazzi style photographs of MVBs first public outings after she left hospital.36 45 Advocate Buikman SC obtained a court order requiring the media to comply with the Press Code and to obtain the curator’s consent before interviewing or photographing MVB. 33 Advocate Buikman SC’s Affidavit, p 881, para 34. 34 Ibid, pp 882, paras 35. 35 Ibid, p 870 para 7; para 9.1. 36 Ibid, Annexure LB 2, pp 896 – 898.

- 19. 19 45.1 However, members of the media continued to violate the court order and published invasive coverage about MVB’s personal life, resulting in a complaint to the Press Ombudsman.37 45.2 These media reports included salacious gossip about MVB’s alleged relationship with a young man, with no possible public interest value.38 46 Given these experiences, Advocate Buikman SC concludes that: 46.1 It would have been perfectly possible for the media to report on this story without identifying MVB; 46.2 The media reporting on MVB has not benefitted her as the media respondents claim, but has made her process of healing and reintegration into her community far more difficult; and 46.3 The ongoing media coverage has been very distressing for MVB and has caused her embarrassment.39 47 In light of these experiences, MVB and other child victims in her position require the protection of section 154(3). 37 Ibid, pp 875 – 876, paras 19 – 22. 38 Ibid, pp 877 – 878, para 25 – 28, Annexure LB 10, pp 923 – 924. 39 Ibid, pp 879 – 882, paras 32 – 37.

- 20. 20 The case of PN 48 PN and his co-accused were charged with the murder of Eugene Terre’blanche. PN was aged 15 at the time of the alleged offence and therefore his trial was conducted in camera, under the provisions of the CJA.40 49 As a result of the intense interest in the matter, the media brought an application to be allowed access to the trial. 49.1 The court granted an order which permitted limited media access to the trial and further prohibited the media from publishing information which could reveal PN’s identity.41 49.2 The media was able to access the trial via video stream from another room in the court building which had closed circuit camera. 49.3 For the whole period of the trial, some two and half years, the media did not reveal PN’s identity.42 50 Judgment was handed down on 22 May 2012 after PN had turned 18. While PN was acquitted of murder, he was found guilty of house breaking with intent to steal.43 50.1 Pursuant to the judgment, the media published PN’s name and had his photographs in their various newspapers, seemingly on the basis that 40 SFA, pp 206 – 207, paras 33, 35. 41 Media 24 v National Prosecuting Authority: In Re S v Mahlangu 2011 (2) SACR 321 (GNP). 42 SFA, p 208, para 38. 43 Ibid, p 208, para 39.

- 21. 21 the automatic protection under section 154(3) of the CPA had lapsed as he was now over 18. 50.2 The protection that PN had received throughout the trial was undone and his identity became well known across the country and in particular in Ventersdorp where he had lived prior to the arrest.44 51 PN became exposed to harm and danger in light of the racial hostility that was heightened in the area following the murder of Terre‘blanche.45 The media respondents deny that he was exposed to any danger,46 but that denial rings hollow given the racially charged atmosphere outside the court (where white and black crowds had to be forcibly separated by police)47 and the fact that an effigy of his co-accused was hung from a tree on the day of sentencing.48 52 PN has since left the Ventersdorp area and could not be traced. In all likelihood, the fact that his identity became widely known compelled him to leave.49 The case of DS 53 DS was charged and convicted with the murder of his family in 2012. He was aged 15 at the time the murder was committed. 44 SFA, pp 208 – 209, paras 41 – 42. 45 Ibid, p 209, para 42 – 43. 46 AA, pp 536 – 537, para 144. 47 SFA, p 207, para 34. 48 Ibid, p 209, para 42. 49 Ibid, p 209,para 44. The media respondents denythis,but they are in no position to give this denial,as they have no personal knowledge of these events. AA, p 536 – 537 , para 144.

- 22. 22 54 The media was allowed to access and report on the trial. While the media did not identify him during the trial, they published articles that speculated on who the murderer might be.50 55 DS was convicted of murder and was sentenced to 20 years in prison on 13 August 2014, just two days before his 18th birthday. He is currently appealing the conviction and sentence.51 56 After DS turned 18, various media houses published DS’s identity and posted pictures of DS on their websites.52 Many of the pictures were taken during the trial, while DS was under the age of 18. Books have also been published on DS’s case, including a book with DS’s picture on the cover.53 57 DS explains the trauma he underwent when suddenly his identity was made public after he turned 18 and was deemed a major. He also fears that he will not be able to return to a normal life on his release, as his identity is now widely known and the media is likely to follow him wherever he goes.54 The case of MO 58 MO was involved in a car accident in January 2011 when he was aged 17. As a result of the accident a man died and two minor children were injured. 50 SFA, p 210, para 47. 51 Ibid, p 210, para 48. 52 DS’s affidavit, p 310, para 11 (English translation). 53 Ibid, p 311, para 319. 54 Ibid, pp 312-313, para 22-29.

- 23. 23 59 MO’s matter was heard in the child justice court. After he turned 18, the public prosecutor obtained an order for the case to continue in camera and that no information revealing his identity would be published.55 60 Despite this prohibition, newspapers proceeded to publish MO’s name in their stories which resulted in him being labelled as a murderer and a drunkard in his community. He also received several threatening phone calls and text messages and general abusive messages from strangers.56 61 The continued abuse and humiliation resulted in MO deregistering from University and continuing his studies through distance learning with UNISA. He was stressed and detached and sometimes had suicidal thoughts as a result of the publicity. MO’s psychiatrist diagnosed him with post-traumatic stress disorder which was largely as a result of his identification in the media.57 62 After having unlawfully published MO’s identity, Independent Newspapers then made an application to rescind the magistrates’ order prohibiting publication of information about MO. However, the matter was never resolved.58 55 MO’s affidavit, p 452, para 7. 56 Ibid, pp 452 -453, paras 7-9. 57 Ibid, pp 453- 454, paras 10-12. 58 Ibid, pp 454-455, paras 17-19.

- 24. 24 The cases of P and X 63 The experiences of KL, MVB, PN, DS and MO stand in contrast with the examples of two young women, P and X. These women were both child offenders and were both convicted of very serious offences. Despite widespread media coverage of both cases, neither P nor X were named by the media. 63.1 This appears to have been largely fortuitous — P and X turned 18 sometime after their court proceedings had concluded, when media interest in their cases had subsided. 63.2 As a result, they were spared the ordeal of being identified in the media when they reached adulthood. 63.3 Their experiences show that anonymity can allow victims, witnesses, accused and offenders the opportunity to overcome trauma and to live normal, productive lives. 63.4 However, their examples also indicate that this anonymity remains precarious so long as the media believes that section 154(3) does not protect child victims, witnesses, accused and offenders into adulthood. 64 P was convicted of murdering her grandmother, a crime she committed when she was 12 years old. Despite her story having been widely publicised in the media, P was never identified.59 59 SFA, p 216, para 62-63.

- 25. 25 64.1 P was subjected to media scrutiny daily as she attended court and the media took pictures of her although they could not use the pictures as they were not allowed to identify her. 64.2 P received a non-custodial sentence which was converted to a suspended sentence on appeal and remained at home and attended school. 64.3 P matriculated in 2007 and studied cosmetology at an FET College. She did various job and was married in 2011. P’s husband and his family knew about the case and her conviction but accepted her as she is. P is now a mother with two children and is in a happy and stable family.60 64.4 P explains that though the media occasionally wants to speak to her, the attention died down after the case and she has been able to live a normal life centred on her children and family. 64.5 P expresses her concern that should her name be identified in the media; she would not be able to cope with her identity and past being made public as she tries not to dwell on the past but rather focus on the present and raising her family. P further explains that if she were to be identified, she would not be able to explain the situation to her children and is concerned about the impact the details that she 60 P’s affidavit, pp 331-332, para 10-15.

- 26. 26 murdered her grandmother would have would have on their lives if they found out about her past and her being described as the “killer girl”.61 64.6 Ms Van Niekerk, a social worker, who assisted P in the rehabilitative process explains in her supporting affidavit that P was a vulnerable and emotionally unstable child who with the right interventions has grown to be a well-adjusted woman and exposure to the media would be disruptive of all the progress she has made.62 65 X was convicted when she was 16 for being an accessory after the fact to the murder of her parents. Her parents were murdered by her boyfriend at the time. She became a victim and an accused.63 65.1 X was meant to testify at the trial, however the accused pleaded guilty and X was spared the ordeal of testifying.64 65.2 X was moved to a children’s home and only people who needed to know about her conviction were informed. She went to school and completed her matric and is currently studying for a Bachelor of Arts in psychology and English with UNISA.65 65.3 X is now married and has three children. She states in her affidavit that her healing process during her teenage years was slow and difficult. 61 Ibid, p 333, para 20-24. 62 Supporting affidavit by Joan Van Niekerk, p 344-345 para 20.2 -20.5. 63 X’s affidavit, p 351, para 2-3. 64 Ibid, p 351, para 3. 65 Ibid, p 352, paras 9 – 12.

- 27. 27 She explains how anonymity allowed her to transition into adulthood and assisted in her process of healing.66 65.4 Ms Van Niekerk, who also had the opportunity to work with X, states that while X’s childhood was compromised by neglect and addictions, anonymity allowed her to settle in her new environment without fear of the stigma attached to the crime she had committed. Ms Van Niekerk notes that X has sufficiently rehabilitated and has a stable family but that if her identity was to be disclosed in the media, it would negatively affect her, her children, and the community.67 66 It is important to bear in mind that if the applicants do not obtain the relief sought in Part B of this application, then P and X will remain in danger of being identified in the media. This would undermine all the work that has gone into their rehabilitation and reintegration. Expert evidence on the harms of identification 67 The experiences of KL, MVB, PN, DS, MO, P and X are not isolated examples. 67.1 Research by Media Monitoring Africa (“MMA”), the fifth applicant, suggests that in 2003 over 33 per cent of stories on crimes involving children identified the children.68 66 Ibid, pp 353 – 354, paras 13 – 14, 20-22. 67 Supporting affidavit by Joan Van Niekerk, p 345 paras 21.1 – 21.5. 68 Supporting affidavit by William Bird, p 394, para 11.2; Annexure WRB 2, pp 424 – 426.

- 28. 28 67.2 In a 2013 study, MMA identified no less than 274 examples of stories that violated the rights of children.69 68 These children’s experiences are also indicative of the serious harms and risks that other child victims, witnesses, and offenders may suffer if they are identified in the media. 69 To understand the gravity of the problem, it is important to consider the serious impact on each child, rather than merely considering the numbers of those affected. 70 Identification in the media can have a catastrophic impact on the lives of the children affected, as is explained in the papers by no less than four leading experts. These experts are: 70.1 Professor Ann Skelton, director of the Centre for Child Law, recently appointed member of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, and an expert on child justice. She has assisted many child victims, witnesses and offenders in criminal law matters over her career of more than 25 years.70 70.2 Dr Giada Del Fabbro, a psychologist with considerable clinical, assessment and therapeutic experience in the field of child and adolescent psychology.71 69 Further supporting affidavit by William Bird, p 964, para 7. 70 FA, SFA and Replying Affidavit. 71 Report by Dr Del Fabbro, Annexure AMS 37, pp 370 – 388; Annexure AMS 50, pp 950 – 954.

- 29. 29 70.3 Ms Joan van Niekerk, former director of Childline and a social worker with 27 years’ experience who has worked with thousands of child victims and many child offenders.72 70.4 Ms Arina Smit, manager of NICRO’s clinical unit, who has worked with over a thousand child offenders over the past 17 years.73 The harms caused by identification 71 The experts have identified four types of psychological harms that flow from identification of children in the media and other public forums: 71.1 Trauma and regression; 71.2 Stigma; 71.3 Shame; and 71.4 The fear of being identified. 72 As Dr Del Fabbro explains: 72.1 These vulnerabilities persist after 18, particularly where a child’s psychological development has been disrupted by the combined traumas of crime and participation in the criminal process.74 72 Supporting affidavit by Ms Van Niekerk, Annexure AMS 34, pp 335 – 348. 73 Supporting affidavit by Ms Smit, Annexure AMS 35, pp 356 – 369. 74 Dr Del Fabbro’s report, p 379, para 25.

- 30. 30 72.2 Moreover, child victims, witnesses, accused or offenders are in particular need of ongoing protection for their anonymity after they turn 18. This is because childhood traumas have particularly lasting effects, leaving wounds that may be reopened if these children are publicly identified in adulthood.75 73 In what follows, we briefly summarise the psychological evidence on these harms. Trauma and regression 74 Crime traumatises children in particularly severe, life-altering ways. Children’s identities are still developing, their defence and coping mechanisms are not yet fully formed, and they experience stigma and shame acutely. As a result, crime leaves children with deep psychological scars that can remain throughout their adult lives.76 75 It is not only victims and witnesses that are traumatised by crime. Children who commit crimes are also traumatised by their actions and the consequences. As Ms Smit explains: “What is not generallyunderstood is that the offence committedby a child offender is also a traumatic event for that child offender. Trauma identification and treatment is essential to provide the child with the necessary emotional support and to ensure the child receives the correct intervention to modify the child’s behaviour.”77 75 Ibid, pp 379 – 380, at paras 27 – 33. 76 SFA, pp 223, para 86; Dr Del Fabbro’s report, pp 373 – 374, paras 6 – 12. 77 Affidavit by Ms Smit, p 360, para 12.

- 31. 31 76 This is reflected in the experiences of X, who was both a victim of a crime and an accessory after the fact. She had to overcome the trauma of the murder of her parents and her own feelings of guilt around her involvement in the crime. 77 Adults who have experienced childhood trauma on this scale remain at great risk of “regression” if identified in the media. Dr Del Fabbro explains that regression occurs when a person is confronted with triggers that take them back to the feelings and emotions experienced at the time of the traumatic event. In Dr Del Fabbro’s opinion, identification in the media is a particularly powerful trigger. 77.1 When an adult is identified as having been a child victim, witness, accused or offender, they are again taken back to the point of trauma. 77.2 They may be confronted with photographs of themselves as children and deeply intimate personal details which trigger a flood of traumatic memories. 77.3 They also have to contend with the stigmatising effects of this coverage, as others will now know their identity and what they did or experienced in childhood. 77.4 Identification in the media also results in a multiplication of publicity, as the story may be republished, posted on the internet in perpetuity, and spread through schools, places of work, and communities.

- 32. 32 77.5 As a result, the adult may be confronted with the story again and again, wearing down their defences.78 78 As a result of this publicity, an adult is likely to regress to the state of trauma they experienced while they were a child. Dr Del Fabbro states: “This would erode all of the support structures and coping mechanisms they may have developed since the traumatic event. The person will re-experience all of the feelings of fear, isolation and mistrust that they experienced at the time of the trauma…. This regression can undo years of therapy and rehabilitation and increase hopelessness regarding future possibility of recovery”79 Shame 79 Identification in the media and other public forums can evoke intense feeling of shame in a child. Dr Del Fabbro explains children often experience shame more acutely than adults, causing children further trauma and suffering.80 80 Although feeling shame may be part of what must happen for an offender to be held accountable, our courts have recognised that shame must be “reintegrative” rather than “stigmatizing”.81 80.1 This is what is intended by a restorative justice approach. Restorative justice is one of the objectives of the Child Justice Act and is specifically mentioned in the section 2(b)(iii) of that Act 78 Dr Del Fabbro’s report, p 380, paras 34 – 39. SFA, p 224 – 225, para 90. 79 Dr Del Fabbro’s report, p 380, para 37. 80 SFA, pp 226 – 227, paras 94 – 96; Dr Del Fabbro’s report, pp 374 – 375, paras 13 – 14. 81 See: S v Saayman 2008 (1) SACR 393 (E).

- 33. 33 80.2 It is therefore particularly important when dealing with child offenders that any shame that they feel should be channelled usefully into their understanding of the effect of their behaviour on others. 80.3 For this to happen, shame can be expressed in processes that aim to achieve the reintegration of the child back into society. 80.4 However, all of this taking responsibility, feeling shame, and making amends is done in sessions facilitated by a suitably qualified person. It does not happen in public. 80.5 The public identification approach contended for by the media is quite different. It involves a stigmatising shame and will often impede the achievement of restorative justice. 81 When it comes to child victims or witnesses, it might be thought that there is no reason for them to be ashamed. 81.1 However, children often attribute bad things happening to them as being partly their own fault, and feel ashamed of their own role or their own inability to stop those things happening. 81.2 As the offences to which they are witnesses or are victims are often committed by family members who they are attached to, they also feel the deflected shame of the acts of the offender. 81.3 For example, KL knows that she has done nothing wrong, but she also cannot easily detach herself from the acts of the kidnapper, her love for the person who has raised her, and her discomfort that her biological

- 34. 34 parents suffered as a result of her disappearance while she herself was living a normal life.82 82 It is for this reason that victims and witnesses also require anonymity in order to avoid association with what they may view as shameful events. Stigma 83 Shame and stigma are not the same thing. Stigma attaches to people when their shame is publicly known and, to some extent, defines them in the eyes of others. They are forever branded with some deeply discrediting attribute, both in their own minds and in the minds of others.83 84 All of the individuals who have provided affidavits express anxiety about the stigmatisation that results from public identification: 84.1 In her affidavit X explains that she was able to heal because she could start afresh and “live a new life in which people don’t judge me”.84 84.2 P makes her own powerful statement about stigma: ‘[B]eing known forever by everyone for something bad that you did when you were a child can, in a way, be the end of your life’.85 She also says that she does not want her children to see her labelled as being the “killer girl”.86 82 Dr Del Fabbro’s report, pp 382 – 383, para 44 – 53; confirmed in the affidavit of Leana Goosen, pp 945 – 949. 83 SFA, pp 228 – 229, paras 97 – 99. 84 KL’s affidavit, p 63, para 19. 85 P’s affidavit, p 334, para 29. 86 Ibid, p 333, para 24.

- 35. 35 84.3 Similarly DS, does not want to forever be known as “the Griekwastad murderer”.87 84.4 KL explains that “[I]f the media is allowed to reveal my identity … I will always be known as the girl who was kidnapped at birth. I don’t want this fact to forever define me in the eyes of others”.88 85 The stigma that comes from being identified in the media is destructive of a child’s healing and reintegration into their communities. We return to this theme below. The fear of identification 86 A child who fears being identified in the media may experience added trauma. The child will also have to live with this insecurity and fear throughout their adult lives, never knowing when they might be publicly identified.89 87 Dr Del Fabbro observes that child victims, witnesses, accused, and offenders may be under a state of constant anxiety that their past may resurface at the whim of the media. She notes that the tendency of the media to “heighten dramatic effect” and “exaggerate disaster, chaos and unpredictability of modern life” plays into this insecurity that children feel.90 87 DS’s translated affidavit, p 310, para 9 88 KL’s affidavit, p 63, para 20. 89 SFA, pp 229 – 231, paras 100 – 107. 90 Dr Del Fabbro’s report, p 373, para 10.

- 36. 36 88 This fear can have a profound effect on children and the choices they make. They may feel intense despair, powerlessness and hopelessness at the prospect of being identified. Dr Del Fabbro indicates that this may result in an increased risk of depression and even suicide.91 89 This fear of identification also has lasting effects into adulthood. Adults must then live with the constant anxiety that their lives may be upended if the media chooses to identify them. X describes this fear in moving terms: “Although my life is whole and I am healed, there remains this small speck on the horizon – the ‘secret’ I must always live with. If the media was allowed to blow that speck into a huge thing, then it will take me way, way back. If my identity was revealed now, I would be devastated. It would affect my husband’s career, in the future it would affect my children. I worry about what type of things the media might print – they might tell it wrong. It would have a hugely negative impact on my life and stability.”92 This insecurity puts an added burden on adults like X who are trying to overcome the trauma of their childhood. 90 Trauma, shame, stigma and the fear of identification are common to child victims, witnesses, accused and offenders alike. In Parts 3 and 4, we explain how identification in the media and other public forums also has specific impacts on victims and witnesses, on the one hand, and accused and offenders, on the other. 91 Ibid, p 381, paras 40 – 43. 92 X’s affidavit, p 354, paras 20 – 21.

- 37. 37 The media respondents’ response to the expert evidence 91 The media respondents concede the vast majority of this expert evidence on the harms of identification: 91.1 They do not dispute the evidence on the different forms of psychological harm arising from identification;93 91.2 They explicitly concede the evidence on the harms of identification of offenders, specifically that disclosure may “hinder the rehabilitation and reintegration of offenders, and may engender feelings of shame and stigma.”94 91.3 They also admit that victims of sexual offences and child abuse would suffer severe harms if identified by the media.95 92 However, the applicants go on to deny that child victims of crimes, apart from sexual violence and child abuse, generally suffer harm as a result of having their identities revealed in the media or other public forums. They contend that “it is not generally true that it is harmful to be known as a victim of a crime”.96 93 The respondents put up no expert evidence of their own to support these sweeping claims and denials. Instead, these claims are made by a deponent 93 AA, pp 541, para 149.1. 94 AA, p 513, para 102. 95 AA, p 482, para 49. 96 AA, p 481, para 45.

- 38. 38 with no expertise in this area – she is a legal editor of the Sunday Times97 – who merely relies on a collection of press clippings. 94 In addition, the media respondents assert that Dr Del Fabbro’s expert evidence only applies to victims of sexual violence and child abuse, despite Dr Del Fabbro’s repeated emphasis that all victims may experience these harms.98 95 In Teddy Bear Clinic for Abused Children v Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development, the Constitutional Court dealt with a situation where one side presents expert evidence and the other does not properly counter it with expert evidence of its own. It explained as follows: “I pause to emphasise two points. First, where one party has put forward cogent expert documentary evidence indicating that the impugned provisions do not pass constitutional muster, the party seeking to uphold the validity of those provisions must advance evidence of a similar nature if he or she is to have any hope of success. …. Second, in matters concerning children, it is particularly important that courts be furnished with information of the best quality that can reasonably be obtained.”99 96 Sweeping statements by an unqualified deponent and press clippings are not “evidence of a similar nature” in response to the applicants’ expert evidence. 97 Therefore, the harms identified by the applicants’ experts must be accepted as well-founded. 97 AA, p 462, para 2. The deponent is a legal editor of the Sunday Times. 98 Supporting affidavit of Dr Del Fabbro, pp 951 – 953, paras 6 – 9; Reply, p 815, para 48.2. 99 Teddy Bear Clinic for Abused Children v Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development 2014 (2) SA 168 (CC) at para 96.

- 39. 39 PART 2: THE RIGHTS AT STAKE 98 We now turn to address the constitutional rights at stake in this case. Two sets of rights are in issue: 98.1 On the one side of the scales are the constitutional rights of children, including the section 28(2) right that a child’s best interests are of paramount importance, the section 9 right to equality, the section 10 right to dignity, the section 14 right to privacy, and the section 35(3) right to a fair trial. 98.2 On the other side of the scales are the section 16 right to freedom of expression, including media freedom, and the overarching principle of open justice. 99 These rights and interests must be seen in the context of the state’s section 7(2) constitutional duty to respect, protect, promote and fulfil all rights under the Bill of Rights. Section 154(3) of the CPA is an attempt by the state to fulfil its constitutional duties to protect the rights and best interests of children. It must be understood in light of this protective purpose. The best interests of the child 100 The starting point in this matter is the section 28(2) guarantee, which provides: “A child’s best interests are of paramount importance in every matter concerning the child.” 101 Section 28(2) is both a principle and a self-standing right:

- 40. 40 “[T]he ‘best-interests’ or ‘paramountcy’ principle creates a right that is independent and extends beyond the recognition of other children’s rights in the Constitution.”100 102 Paramountcy requires that children’s interests are to be afforded the “highest value”,101 meaning that their interests are “more important than anything else” albeit that “everything else is [not] unimportant.”102 103 This recognises that children’s interests are in need of special protection as a result of their vulnerability and their capacity for development. 103.1 In Centre for Child Law v Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development and Others, the Constitutional Court explained this in the following terms: “The Constitution draws this sharp distinction between children and adults not out of sentimental considerations, but for practical reasons relating to children’s greater physical and psychological vulnerability. Children’s bodies are generally frailer, and their ability to make choices generally more constricted, than those of adults. They are less able to protect themselves, more needful of protection, and less resourceful in self-maintenance than adults.”103 103.2 In Teddy Bear Clinic, the Constitutional Court added that: “Children are precious members of our society and any law that affects them must have due regard to their vulnerability and their need for guidance. We have a duty to ensure that they receive the support and assistance that is necessary for their positive growth and development. Indeed, this Court has recognised that children 100 J v NDPP 2014 (2) SACR 1 (CC) at para 35 (“J v NDPP”). See also Minister of Welfare and Population Development v Fitzpatrick and Others 2000 (3) SA 422 (CC) (Fitzpatrick) at para 17; 101 S v M (Centre for Child Law as Amicus Curiae) 2008 (3) SA 232 (CC) at para 42. 102 Centre for Child Lawv Minister of Justice and Constitutional Developmentand Others 2009 (6) SA 632 (CC) at para 29 (“Centre for Child Law”). 103 Ibid at paras 26-9 (emphasis added)

- 41. 41 merit special protection through legislation that guards and enforces their rights and liberties.” 104 104 While the law can never guarantee that children are insulated from all traumas, section 28(2) requires that the law must do as much as possible to create conditions that protect children, allowing them to lead flourishing lives. As the Constitutional Court held in S v M:105 "No constitutional injunction can in and of itself isolate children from the shocks and perils of harsh … environments. What the law can do is create conditions to protect children from abuse and maximise opportunities for them to lead productive and happy lives."106 105 Section 28(2) also requires that any decision which may have detrimental consequences for a child’s interests should allow for individualised assessment. The blanket deprivation of a child’s rights, without individualised assessment, is a violation of this right: “Child law is an area that abhors maximalist legal propositions that preclude or diminish the possibilities of looking at and evaluating the specific circumstances of the case. . . . This means that each child must be looked at as an individual, not as an abstraction.”107 The principle of ongoing protection 106 Section 28(2) embodies a further principle that is of central significance for this case. We will refer to this as the “principle of ongoing protection”. 104 Teddy Bear Clinic for Abused Children and Another v Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development 2014 (2) SA 168 (CC) at para 1 (emphasis added) 105 S v M (Centre for Child Law as Amicus Curiae) 2008 (3) SA 232 (CC). 106 Ibid at para 20. 107 AD and Another v DW and Others (Centre for Child Law as Amicus Curiae; Department for Social Development as Intervening Party) 2008 (3) SA 183 (CC) at para 55.

- 42. 42 106.1 This principle provides that the protection afforded by the section 28(2) right does not necessarily terminate when a child turns 18. 106.2 The life-long consequences of a child’s actions or experiences are also the proper concern of section 28(2), even if those consequences are only felt in adulthood. 107 The Constitutional Court has consistently affirmed this principle of ongoing protection in the context of sentencing child offenders. 108 In J v NDPP,108 the Constitutional Court struck down a provision of the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act which required the compulsory inclusion of children who committed sexual offences on the Sexual Offences Register, without affording courts a discretion. 109 The Court held that while the consequences of registration on the Sexual Offences Register would largely be experienced in adulthood, those consequences were the proper concern of section 28(2): "[T]his Court has held that consequences for the criminal conduct of a child that extend into adulthood (such as minimum sentences) do implicate children’s rights. So, in the case of J, the fact that he was a child when the offence was committed means that his rights as a child are implicated, albeit that the consequences of registration will, for the most part, only be felt as an adult."109 (Emphasis added) 108 J v National Director of Public Prosecutions 2014 (2) SACR 1 (CC). 109 Ibid at para 43.

- 43. 43 110 J affirmed and made explicit the principle of ongoing protection that was implicit in the Court’s 2009 judgment in Centre for Child Law. 111 In Centre for Child Law110 the Constitutional Court held that the application of minimum sentencing laws to offenders who were 16 and 17 years old at the time of the offence was unconstitutional, even if those offenders were over the age of 18 at the time of sentencing. The Court did so recognising that child offenders are physically and psychologically more vulnerable than adults, that they have diminished moral responsibility for their conduct, and greater capacity for reform: “These are the premises on which the Constitution requires the courts and Parliament to differentiate child offenders from adults. We distinguish them because we recognise that children’s crimes may stem from immature judgment, from as yet unformed character, from youthful vulnerability to error, to impulse, and to influence. We recognise that exacting full moral accountability for a misdeedmight be too harsh because they are not yet adults. Hence we afford children some leeway of hope and possibility.”111 112 The effect of J v NDPP and Centre for Child Law is that, for the purposes of section 28(2) of the Constitution, what matters is not when the consequences are felt, but whether those consequences flow from actions or events occurring during childhood. 113 This principle of ongoing protection is of wider application than merely sentencing of child offenders. This is because the reasons for this principle have equal application to all children, including victims and witnesses of crime: 110 Centre for Child Lawv Minister of Justice and Constitutional Developmentand Others 2009 (6) SA 632 (CC). See also Mpofu v Minister for Justice and Constitutional Developmentand Others 2013 (2) SACR 407 (CC). 111 Ibid at para 28.

- 44. 44 113.1 As the Constitutional Court has recognised, the consequences of childhood experiences and conduct that are felt in adulthood tend to be more severe, because of the greater physical and psychological vulnerability of the child.112 113.2 Moreover, the Court has acknowledged that a child has lesser moral responsibility for what they do or what happens to them in childhood. They are also more “malleable”, as they have a greater capacity for development and healing. For this reason, it is impermissible to unduly punish an offender for actions in their childhood. But there must then equally be a need to protect child victims and witnesses from the consequences of crimes committed against them or in their presence, for which they are blameless. These victims and witnesses must be given the same prospect of “hope and possibility”that is afforded to child offenders.113 114 When it is acknowledged that section 28(2) continues to protect child victims, witnesses, accused and offenders into adulthood, there is no proper basis to deny these children protection under section 154(3) of the CPAwhen they turn 18. We will return to discuss this principle of ongoing protection in Part 4. Privacy and dignity 115 The section 14 right to privacy and the section 10 right to human dignity are also implicated when a child is stripped of their anonymity. 112 Ibid at paras 26 – 27. 113 Ibid at para 27.

- 45. 45 116 The Constitutional Court has recognised a continuum of privacy interests, with intimate personal information at the core of this right. “A very high level of protection is given to the individual’s intimate personal sphere of life and the maintenance of its basic preconditions and there is a final untouchable sphere of human freedom that is beyond interference from any public authority. So much so that, in regard to this most intimate core of privacy, no justifiable limitation thereof can take place.”114 117 Where a child has been a victim, witness or perpetrator of a crime, that child’s identity will be a deeply private fact, the disclosure of which would cause mental distress and injury to any reasonable person in their position.115 118 As the expert evidence and the experiences of the children and young persons above shows, child victims, witnesses and offenders have a strong privacy interest in retaining their anonymity during their childhood and into their adulthood. 119 This requires the state to protect children from intrusions into their privacy from state officials and private persons alike: “An implicit part of this aspect of privacy is the right to choose what personal information of ours is released into the public space. The more intimate that information, the more important it is in fostering privacy, dignity and autonomy that an individual makes the primary decision whether to release the information. That decision should not be made by others. This aspect of the right to privacy must be respected by all of us, not only the state.”116 (Emphasis added) 114 Bernstein and Others v Bester NO and Others 1996 (2) SA 751 (CC) at para 77. 115 National Media Ltd and Another v Jooste 1996 (3) SA 262 (A) at 270I-J. Adopted in NM v Smith 2007 (5) SA 250 (CC) at paras 34 (Madala J) and 137 (O’Regan dissent),albeitwithoutdeciding whether itremains appropriate to the constitutional context. 116 NM v Smith ibid at para 132 (emphasis added).

- 46. 46 120 A child’s right to privacy is closely intertwined with their right to the protection of human dignity. As the Constitutional Court has explained in a case concerning children, “An individual’s human dignity comprises not only how he or she values himself or herself, but also includes how others value him or her.117 121 The Court has consistently held that public shaming, stigma and humiliation of children are antithetical to the right to human dignity. In J v NDPP,118 the Court went further in holding that the mandatory listing of a child on the sexual offences register would have lifelong stigmatising effects that were in violation of their rights to dignity and to have their best interests protected: “Child offenders who have served their sentences will remaintarred with the sanction of exclusion from areas of life and livelihood that may be formative of their personal dignity, family life, and abilities to pursue a living.”119 122 Similarly, in Toronto Star Newspaper Ltd v Ontario,120 the Ontario Supreme Court of Justice succinctly explained the importance of anonymity protections for children as a means of protecting their dignity and privacy: “The concern to avoid labeling and stigmatization is essential to an understanding of why the protection of privacy is such an important value in the Act. However it is not the only explanation. The value of the privacy of young persons under the Act has deeper roots than exclusively pragmatic considerations would suggest. … Privacy is recognized in Canadian constitutional jurisprudence as implicating liberty and security interests. In Dyment, the court stated that privacy is worthy of constitutional protection because it is “grounded in man’s physical and moral autonomy,” is “essential for the well-being of the individual,” and is 117 Teddy Bear Clinic for Abused Children and Another v Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development 2014 (2) SA 168 (CC) at para 56. 118 J v National Director of Public Prosecutions 2014 (2) SACR 1 (CC). 119 Ibid at para 44. 120 Toronto Star Newspaper Ltd v Ontario 2012 ONCJ 27 (CanLII).

- 47. 47 “at the heart of liberty in a modern state” (para. 17). These considerations apply equally if not more strongly in the case of young persons. Furthermore, the constitutional protection of privacy embraces the privacy of young persons, not only as an aspect of their rights under section 7 and 8 of the Charter, but by virtue of the presumption of their diminished moral culpability, which has been found to be a principle of fundamental justice under the Charter.”121 This analysis has great resonance with the South African jurisprudence on privacy and dignity. Equality 123 As we explain in Part 3, the potential exclusion of child victims also implicates the section 9 right to equality. Of particular importance is the section 9(1) guarantee that “[e]veryone is equal before the law and has the right to equal protection and benefit of the law.” 123.1 This requires that differentiation between persons in law or its application must be rationally connected to a legitimate government purpose.122 123.2 The purpose of this protection is to ensure that “similarly situated persons” should not “suffer any greater disability in the substance and application of the law than others.”123 121 Toronto Star Newspaper ibid at paras 40 – 41, 44 (emphasis added).Cited with approval by the Supreme Court of Canada in AB v Bragg [2012] 2 SCR 567 at para 18. 122 Sarrahwitz v Maritz NO and Another 2015 (4) SA 491 (CC) at para 54. 123 Madala J in Van der Walt v Metcash 2002 (4) SA 317 (CC) at para 68 (writing in dissent, but the principle cannot be disputed).

- 48. 48 124 The Constitutional Court’s recent judgment in Sarrahwitz v Maritz NO and Another124 confirms that where a law seeks to protect a vulnerable class of persons, it is impermissible and in violation of section 9(1) to exclude others who are equally vulnerable, unless this is rationally connected to a legitimate purpose. Fair trial rights 125 The question of whether anonymity protections for child offenders are lost when they turn 18 has a direct impact on their section 35(3) fair trial rights. 126 In S v Zuma, and the long line of cases that have followed, the Constitutional Court has affirmed that the section 35(3) rights to a fair trial encompass both procedural and substantive fairness.125 As we explain in Part 4, automatically stripping a child offender of anonymity on turning 18 threatens to deprive a child of these procedural and substantive fair trial rights. Freedom of expression and open justice 127 Anonymity protections for children in the criminal justice system do have an impact on freedom of expression and open justice. However, this impact is a very limited one. Moreover, section 154(3) of the CPA allows courts to achieve a balance between children’s rights, on the one hand, and the rights to freedom of expression and open justice on the other. 124 Sarrahwitz v Maritz NO and Another 2015 (4) SA 491 (CC) at para 49. 125 S v Zuma and Others 1995 (2) SA 642 (CC) at para 16.

- 49. 49 128 The relationship between anonymity protections, media freedom, and open justice have already been analysed in detail by the South African Constitutional Court and by foreign courts. This analysis is highly significant for this case. Anonymity protections in South African law 129 The Constitutional Court has consistently recognised that anonymity protections are not a significant incursion into freedom of expression or open justice. 130 In NM v Smith, the Constitutional Court addressed a breach of privacy claim brought following the naming of three HIV-positive women in a book. The Court held that the respondents “could have used pseudonyms instead of the real names of the applicants. The use of pseudonymswould not have rendered the book less authentic”.126 131 Moreover, the Constitutional Court has itself used anonymity protections as the means to hold the balance between freedom of expression, open justice, and the rights of vulnerable groups. 131.1 In Johncom Media Investments Limited v M,127 the Constitutional Court imposed a ban on the publication of information that reveals or may reveal the identity of children and parties involved in divorce 126 NM v Smith 2007 (5) SA 250 (CC) at paras 45-46 (emphasis added) 127 Johncom Media Investments Limited v M 2009 (4) SA 7 (CC).

- 50. 50 proceedings, holding that this would protect children’s rights while preserving media freedom. 131.2 Johncom concerned a challenge to section 12 of the Divorce Act, which prohibited the publication of any information arising from divorce proceedings, but allowed for publication of the names of parties to the proceedings, including affected children. 131.3 The Constitutional Court held that this blanket prohibition on any information arising from these proceedings was an unjustified limitation of the right to media freedom, a component of freedom of expression. In particular, it held that anonymity protections were a less restrictive means available to protect the rights of children and the privacy of divorcees: “Another way to protect children and parties would, in my view, be to prohibit publication of the identity of the parties and of the children. If that were to be done, the publication of the evidence would not harm the privacy and dignity interests of the parties or the children, provided that the publication of any evidence that would tend to reveal the identity of any of the parties or any of the children is also prohibited.”128 131.4 The Court therefore struck down section 12, but substituted it with an order in the following terms, closely resembling section 154(3) of the CPA: “Subject to authorisation granted by a court in exceptional circumstances, the publication of the identity of, and any information that may reveal the identity of, any party or child in any divorce proceeding before any court is prohibited.”129 128 Ibid at para 30. 129 Ibid at para 45.

- 51. 51 131.5 The Court held that this anonymity protection struck the best possible balance between freedom of expression, on the one hand, and the rights to privacy and best interests of the child on the other. “[T]his court could in terms of s 172(1) prohibit all publication of the identity of and any information that may reveal the identity of any party or child in any divorce case before any court. This is the position adopted in the Child Care Act. It is also important to emphasise that this court has adopted the approach of not disclosing the identities of children and vulnerable parties in all appropriate cases. In my view, this is an appropriate order. Such an order will not place an undue burden on the courts nor will it impose a particular burden on parties seeking publication or those parties seeking remedies on the basis that they may be prejudiced by publication.”130 131.6 Furthermore, the Court stressed that by allowing courts to have the final say on whether to lift these anonymity protections, this was in keeping with the court’s role as upper guardian of the child.131 132 As the Constitutional Court alluded to in Johncom, the use of anonymization has become a standard practice in Constitutional Court judgments where children are involved.132 This allows the courts to protect the rights of children while still allowing the media and other parties to report fully on the facts and circumstances of the case, insofar as they do not identify the child. 133 Furthermore, anonymization is also a requirement of Children’s Court proceedings. Section 74 of the Children's Act 38 of 2005 establishes 130 Ibid at para 42. 131 Ibid at para 43. 132 See, for example, J v National Director of Public Prosecutions and Another 2014 (2) SACR 1 (CC) at fn 3; AD and Another v DW and Others (Centre for Child Law as Amicus Curiae; Department of Social Development as Intervening Party) 2008 (3) SA 183 (CC); S v M (Centre for Child Law as Amicus Curiae) 2008 (3) SA 232 (CC).

- 52. 52 automatic and indefinite anonymity protections which may only be lifted with the permission of the court: “No person may, without the permissionof a court, in any manner publish any information relating to the proceedings of a children’s court which reveals or may reveal the name or identity of a child who is a party or a witness in the proceedings.” 134 These examples demonstrate that anonymity protections are already a common feature of our law and are the preferred means to balance the protection of vulnerable individuals with media freedom and open justice. Anonymity protections in foreign law 135 In other jurisdictions, courts, and legislators have also acknowledged that anonymity protections for children generally have no material impact on media freedom and open justice.133 136 The Supreme Court of Canada’s views on anonymity protections are particularly instructive. The Canadian jurisprudence on freedom of expression and open justice is closely aligned with the South African approach, and has often been used as a source of guidance by South African courts.134 Furthermore, the Supreme Court of Canada has provided some of the most extensive analysis of the need for anonymity protections for children of any common law jurisdiction. 133 See the examples provided at paras 188 – 10 and paras Error! Reference source not found. – Error! ference source not found. below. 134 See, for example, Print Media South Africa and Another v Minister of Home Affairs and Another 2012 (6) SA 443 (CC) at para 45; City of Cape Town v South African National Roads Authority Limited and Others 2015 (3) SA 386 (SCA) at paras 12, 14, 25.

- 53. 53 137 In Canadian Newspapers Co v Canada (Attorney General)135 the Canadian Supreme Court upheld a ban on the publication of the identities of victims of sexual offences, holding that anonymity protections impose minimal restraints on media freedom and open justice: "While freedom of the press is nonetheless an important value in our democratic society which should not be hampered lightly, it must be recognized that the limits imposed by [prohibiting identity disclosure] on the media’s rights are minimal. . . . Nothing prevents the media from being present at the hearing and reporting the facts of the case and the conduct of the trial. Only information likely to reveal the complainant’s identity is concealed from the public.”136 (Emphasis added) 138 In FN (RE)137 the Canadian Supreme Court acknowledged that anonymity protections for children are among the permissible exceptions to the open justice principle: “It is an important constitutional rule that the courts be open to the public and that their proceedings be accessible to all those who may have an interest. To this principle there are a number of important exceptions where the public interest in confidentiality outweighs the public interest in openness."138 “The press is entitled to be present … and can publish everything except the identity of a young person involved. Admittedly, there may be other information which the press cannot publishbecause it may tend to reveal the identity of a young person, but the essence of the provision is that the press is entitled to publish all details except one. … [T]he identification of the young person a “sliver of information”.139 139 In AB v Bragg,140 the Canadian Supreme Court applied these principles to a civil case involving a child who was the victim of online bullying. The Court 135 Canadian Newspapers Co v Canada (Attorney General) [1988] 2 SCR 122. 136 Ibid at 133. 137 [2000] 1 SCR 880. 138 Ibid at para 10. 139 Ibid at para 12. 140 [2012] 2 SCR 567.

- 54. 54 again emphasised that the identity of the child is generally a mere “sliver of information” that meant that anonymity protections are a “minimal” incursion on freedom of expression and open justice.141 140 By contrast, the respondents rely on certain dicta in the UK Supreme Court’s 2010 decision in In re Guardian News Media Ltd.142 There the UK Supreme Court suggested that using names in media reports often has value.143 There are series of difficulties for their reliance on these remarks. 140.1 They are inconsistent with the approach of our Constitutional Court in cases such as NM v Smith and Johncom, both mentioned above. 140.2 The judgment makes questionable logical leaps, suggesting that anonymised media reports result in lower readership, falling revenues, and diminished public debate. In the context of reporting on children involved in criminal proceedings, there is simply no evidence to support such sweeping claims. We address this in detail below.144 140.3 Most notably, these remarks were made in the context of anonymity for adults suspected of financing terrorism. That is an entirely different issue to anonymity for vulnerable children. The approach of the UK courts makes this quite clear. In the subsequent case of JXMX v Dartford and Gravesham NHS Trust,145 which addressed the need for 141 Ibid at para 28. 142 In re Guardian News Media Ltd [2010] UKSC 1. 143 See the quotations in AA, pp 504 – 505, para 84. 144 See paragraphs 0 - 226 below. 145 JXMX v Dartford and Gravesham NHS Trust [2015] EWCA Civ 96.