CHART LAW OF TORT for REVISION 2020 complete.docx

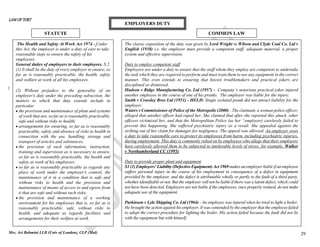

- 1. LAWOF TORT Mrs. Ari Bahmini LLB (Univ of London), CLP (Mal) 29 The classic exposition of the duty was given by Lord Wright in Wilson and Clyde Coal Co. Ltd v English (1938) i.e. the employer must provide a competent staff, adequate material, a proper system and effective supervision. Duty to employ competent staff Employers are under a duty to ensure that the staff whom they employ are competent to undertake the task which they are required to perform and must train them to use any equipment in the correct manner. This even extends to ensuring that known troublemakers and practical jokers are disciplined or dismissed. Hudson v Ridge Manufacturing Co. Ltd (1957) - Company’s notorious practical joker injured another employee in the course of one of his pranks. The employer was liable for the injury. Smith v Crossley Bros Ltd (1951) - HELD: Single isolated prank did not attract liability for the employer. Waters v Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis (2000) - The claimant, a woman police officer, alleged that another officer had raped her. She claimed that after she reported this attack, other officers victimized her, and that the Metropolitan Police (as her “employer) carelessly failed to prevent this happening. She suffered psychiatric injury as a result. She appealed against the striking out of her claim for damages for negligence. The appeal was allowed. An employer owes a duty to take reasonable care to protect its employees from harm, including psychiatric injuries, during employment. This duty is commonly relied on by employees who allege that their employers have carelessly allowed them to be subjected to intolerable levels of stress: for example, Walker v Northumberland CC (1995). Duty to provide proper plant and equipment S1 (1) Employers' Liability (Defective Equipment) Act 1969 makes an employer liable if an employee suffers personal injury in the course of his employment in consequence of a defect in equipment provided by the employer, and the defect is attributable wholly or partly to the fault of a third party, whether identifiable or not. But the employer will not be liable if there was a latent defect, which could not have been detected. Employers are not liable if the employees, once properly trained, do not make adequate use of the equipment. Parkinson v Lyle Shipping Co. Ltd (1964) - An employee was injured when he tried to light a boiler. He brought the action against his employer. It was contended by the employer that the employee failed to adopt the correct procedure for lighting the boiler. His action failed because the fault did not lie with the equipment but with himself. The Health and Safety At Work Act 1974 - Under this Act, the employer is under a duty of care to take reasonable steps to ensure the safety of his employees. General duties of employers to their employees. S 2. (1) It shall be the duty of every employer to ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, the health, safety and welfare at work of all his employees. (2) Without prejudice to the generality of an employer's duty under the preceding subsection, the matters to which that duty extends include in particular the provision and maintenance of plant and systems of work that are, so far as is reasonably practicable, safe and without risks to health; arrangements for ensuring, so far as is reasonably practicable, safety and absence of risks to health in connection with the use, handling, storage and transport of articles and substances; the provision of such information, instruction, training and supervision as is necessary to ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, the health and safety at work of his employees; so far as is reasonably practicable as regards any place of work under the employer's control, the maintenance of it in a condition that is safe and without risks to health and the provision and maintenance of means of access to and egress from it that are safe and without such risks; the provision and maintenance of a working environment for his employees that is, so far as is reasonably practicable, safe, without risks to health, and adequate as regards facilities and arrangements for their welfare at work. STATUTE COMMON LAW EMPLOYERS DUTY

- 2. LAWOF TORT Mrs. Ari Bahmini LLB (Univ of London), CLP (Mal) 30 What is VL?Vicarious liability is a system whereby an employer shall be liable for the tort committed by his employee in the course of employment. Why VL? There are several reasons for the existence of vicarious liability: - 1. The employer is in a better position economically; 2. It is the duty of the employer to ensure that the employee is competent and does his work properly; and 3. The profits of the employee’s work go to the employer. When can a plaintiff go for VL? Vicarious liability arises from a contract of service (employee) and not a contract for services (independent contractors). Therefore, as a general rule, the employer is only liable for the torts of an employee and not that of an independent contractor. How to determine if one is an employee? Control & Intergration test (lost their importance) Economic Reality/Multiple Test - Ready Mixed Concrete (South East) Ltd v Minister of Pensions (1968) HELD: The current test that can be used by the court is the economic test. Under this test, the court will consider the following factors: - a. who takes the profit? B. Who provides the tools of the trade? Mutuality of obligation test - must provide work - O’Kelly v Trusthouse Forte plc [1983] ICR 728 Barclays Bank plc v Various Claimants [2018] EWCA Civ 1670 - In this case, the Court of Appeal had to consider whether there existed a relationship between a wrongdoer and the defendant sufficient to create vicarious liability. Over 100 women brought an action against Barclays Bank, claiming that they had been sexually assaulted in the course of pre-employment medical checks. These were performed on the bank’s behalf by a former GP, who was employed by the bank as an independent contractor over a period from 1969 to 1984. The question for the courts was whether there existed a relationship between the bank and the doctor to found vicarious liability. The first instance judge applied the two-stage test from Cox and Mohamud and concluded that the relationship was sufficiently ‘akin to employment’. This was affirmed by the Court of Appeal, rejecting the bank’s argument that the status of independent was a complete defence to vicarious liability. This conclusion was reached by applying the five criteria laid down by Lord Philips in Various Claimants (2012). Of particular importance for Irwin LJ was criterion 3: ‘that the tortfeasor’s activity (selection of employees) was for the benefit of the Bank and was in fact ‘an integral part of the business activity of the Bank’. It cannot be ignored, further, that here the only available realistic source of compensation was the bank. This clear rejection of the ‘independent contractor’ defence is another indication of the expansion of the law on vicarious liability, as demonstrate by Cox, Armes and other recent case law. Who is responsible for lending employee, the lender or borrower? Q: What is the position where an employer A lends his employee B to another employer C and B commits a tort within the course of his employment? Who will be vicariously liable, A or C? Mersey Docks & Harbour Board v Coggins & Griffith (Liverpool) Ltd (1947) - The Harbour Board was vicariously liable as it had greater control over the driver. In Viasystems v Thermal Transfer [2005] EWCA Civ 1151 4 All ER 1181, the Court of Appeal decided (a) that in principle in cases of borrowed servants there was no reason why both employers should not be vicariously liable and (b) that was the fairest solution to the particular problem. In Biffa Waste Services Ltd v Maschinenfabrik Ernst Hese GmbH [2008] EWCA Civ 1257 the court considered Viasystems and other cases and held that it would be very exceptional for a contractor to be vicariously liable for the negligence of a subcontractor. It also held that the notion that a party could be vicariously liable for the negligence of an independent contractor in respect of ultra-hazardous activities was applicable only in extreme situations. Course of Employment - The employer will only be liable for those torts, which have been committed within the course of employment. If the tort is committed outside the course of work, the employee will be personally liable. Time And Space Stanton v National Coal Board (1957) - HELD: The court came to a conclusion that an employee is still within the course of work when cycling across his employer’s premises to collect his pay. Harvey v R.G. O’Dell Ltd (1958) - HELD: A man was still within his course of work if he was sent to work at different place. Hilton v Thomas Burton (Rhodes) Ltd (1961) - HELD: An employee who is on his lunch break and travels a reasonable distance to obtain his lunch is still within the course of work. However, if the employee travels an unreasonable distance from his place of work for his lunch, he is no longer in the course of work. Nottingham v Aldridge (1971) - The accident - several hours before work started. HELD: The accident did not occur in the course of work. Compton v McClure (1975) - HELD: The employer was vicariously liable as it is he who benefits if the employee clocks in on time. VICARIOUS LIABILITY CARIOUS LIABILITY

- 3. LAWOF TORT Mrs. Ari Bahmini LLB (Univ of London), CLP (Mal) 31 Work Mode Century Insurance v Northern Ireland RTB (1942) - HELD: The D was vicariously liable for the negligence of the driver as unloading the petrol was what he was hired to do. Where the employee carries out his work in a negligent manner, the employer shall be liable. Keppel Bus v Sa’ad bin Ahmad (Privy Council – Singapore) (1974) - HELD: The D was not in the course of work as insulting or assaulting a passenger is not part of a bus conductor’s work. GE v Kingston Corp. (1988) - HELD: The employer was not vicariously liable as going on strike was a clear breach of the contract of employment. Hence the tort was not committed in the course of employment. Rose v Plenty (1976) - HELD: The employer was vicariously liable as the act was done in the course of work i.e. the milkman carried out his work in a negligent manner. The prohibition had not affected the course of the employee’s employment. Lloyd v Grace, Smith and Co (1912) - The D’s clerk fraudulently transferred the P’s property to his name and ran off with the money. P sued D. HELD: D was vicariously liable, as they had placed him in the position that allowed him to commit the fraud. Furthermore as the clerk was paid to do conveyancing, he was within the course of employment. Lister v Hesley Hall Ltd (2001) – HOL -The Ds owned and managed a school, which had a boarding annex. Mr. Grain was employed by the Ds as warden of the annex. The claimants attended the school and boarded in the annex. They were sexually abused by Mr. Grain. The HOL had to decide whether the Ds could be vicariously liable for the sexual abuse committed by Mr. Grain. HELD: The Ds were vicariously liable for the sexual abuse committed by Mr. Grain because ‘the warden’s torts were so closely connected with his employment that it would be fair and just to hold the employers vicariously liable’. LORD STEYN said that Sir John Salmond had propounded a broad test emphasizing the connection between the authorised acts and the "improper modes" of doing them. It was a practical test distinguishing cases where it was or was not just to impose vicarious liability. The usefulness of the formulation was crucially dependent on focusing on the right act of the employee. If Scarman LJ's broad approach to the nature of employment in Rose v Plenty [1976] was adopted it was not necessary to ask whether the warden's acts of abuse were modes of doing authorised acts. The question of vicarious liability could be considered on the basis that the defendants had undertaken to care for the boys through the services of the warden and that there had been a very close connection between those acts and the employment so that it would be fair and just to hold the defendants vicariously liable. Fennelly v Connex South Eastern (2001) CA - A railway ticket inspector X gripped a passenger P in a headlock after P refused to show his ticket. P sued the railway company, D, for vicarious liability. HELD: In preliminary proceedings the CA said the D could be vicariously liable. Buxton LJ said the argument had arisen out of X's performance of his duties, even though he was no longer acting as his employers would have wished. Weir v Chief Constable of Merseyside (2003) CA - Following an argument about personal matters, an off-duty police officer X assaulted the teenage claimant, P, and manhandled him down the stairs and into the back of a police van. HELD: In preliminary proceedings, the CA held that X had been acting "in the course of his employment" at the relevant time: although he had been off-duty, he had identified himself to P as a police officer and had acted as one (albeit very badly), and that was sufficient.

- 4. LAWOF TORT Mrs. Ari Bahmini LLB (Univ of London), CLP (Mal) 32 Mattis v Pollock (2004) - CA A club doorman X stabbed and seriously injured a man, P, during a scuffle in the street, following a serious argument involving P and others in the club some 20 minutes earlier. P now claimed that the club owner D was vicariously liable as X's employer. HELD: Having reviewed at length the five speeches in Lister v Hesley Hall, the trial judge said they showed that vicarious liability can arise if there is such a close connection between the duties which the employee was employed to perform, and the tort committed by him, as to make it fair and just to hold the employer liable, but felt this was not so in the instant case. The Court of Appeal disagreed, and said it was clear that X was expected to use physical force in his work, and the stabbing was directly linked to the earlier incident; it followed that D was vicariously liable. Maga v Trustees of the Birmingham Archdiocese [2010] EWCA - CA took a different view. They said that the law on this issue had been authoritatively laid down by the House of Lords in Lister v Hesley Hall Ltd [2002] 1 AC 215. The correct test laid down by Lord Steyn was whether the abusers torts were so closely connected with his employment that it would be fair and just to hold the employers vicariously liable. Father Clonans sexual abuse of the Claimant was so closely connected with his employment as a priest at the church that it would be fair and just to hold the defendant vicariously liable. Majrowski v Guy’s and St Thomas’s NHS Trust [2006] UKHL 34 - HOL affirmed the decision of the COA that an employer could be vicariously liable where an employee, in the course of his employment, committed a breach of a statutory obligation sounding in damages. Here the claimant alleged that he had been unlawfully harassed by his departmental manager. Gravil v Carroll [2008] a rugby club was held vicariously liable for injury caused by a tortious assault by a player on a member of the opposing team immediately after the final whistle had been blown. The Catholic Child Welfare Society & Ors v Various claimants [2012] - The Court of Appeal had found some defendants (school management trust) not vicariously liable. The other defendants appealed. Supreme Court held: The appeals succeeded. It was fair and just and reasonable for the defendants to share liability [Per Lord Phillips]. In JGE v Portsmouth Roman Catholic Diocesan Trust [2012] EWCA Civ 938, it was held that the relationship between a Roman Catholic priest and his bishop, although not one of contract, was sufficiently akin to a contract of employment to make it fair, just and reasonable to impose vicarious liability. In the Catholic Child Welfare Society case the Supreme Court laid down the idea of control as a central element, and held that an order of brothers could be vicariously liable for abuse by a member of the order who was employed as the head teacher of a school even though the brother was not paid by the order and indeed had to surrender to the order any earnings from his employment. Cox (Respondent) v Ministry of Justice (Appellant) [2016] UKSC 10 On appeal from [2014] EWCA Civ 132 Lord Neuberger (President), Lady Hale, Lord Dyson, Lord Reed, Lord Toulson The Court of Appeal reversed the decision, finding that the prison service was vicariously liable for Mr Inder’s negligence. The question on the MOJ’s appeal to the Supreme Court concerns the sort of relationship which has to exist between an individual and a defendant before the defendant can be made vicariously liable in tort for the conduct of that individual. This case was heard alongside Mohamud v WM Morrison Supermarkets plc [2016] UKSC 11 which addresses the question of how the conduct of the individual has to be related to that relationship, in order for vicarious liability to be imposed on the defendant. JUDGMENT: The Supreme Court unanimously dismisses the Ministry of Justice’s appeal.

- 5. LAWOF TORT Mrs. Ari Bahmini LLB (Univ of London), CLP (Mal) 33 Armes v Nottinghamshire CC [2017] UKSC 60 The question in Armes was whether a local authority was vicariously liable for the physical and sexual abuse perpetrated by the foster parents into whose care they placed the claimant when she was seven years old. The case proceeded on the basis that there was no negligence on the part of the social workers involved with placing the claimant with the foster parents or in the supervision and monitoring of the placements. Nevertheless, the claimant argued that the local authority should be vicariously liable for the wrongful acts of the foster parents. She claimed, alternatively, that the local authority owed her a non-delegable duty to protect her from harm. At first instance, the trial judge rejected vicarious liability and also said that it would not be fair, just and reasonable to impose a non-delegable duty on the local authority. In the context of vicarious liability (relevant for this Chapter), the trial judge considered that it was a crucial and essential feature of foster care that the local authority has no relevant control over the foster parents as to the manner in which, on a day-to-day basis, the foster parents provided family life to the child. The Court of Appeal affirmed the judge’s decision and the matter was then referred to the Supreme Court to consider: (1) whether the relationship between a local authority and foster parents fulfil the criteria for vicarious liability; (2) whether a non-delegable duty is owed by a local authority to a child placed in the care of foster parents. The claim based on a non-delegable duty owed by the local authority was rejected but (by a majority of 4–1) the appeal that the local authority was vicariously liable for the abuse committed by the foster parents was allowed. Lord Reed (with whom Lady Hale, Lord Kerr and Lord Clarke agreed) applied the principles set out in Cox v Ministry of Justice: The general principles governing the imposition of vicarious liability were recently reviewed by this court in Cox v Ministry of Justice. As was said there, the scope of vicarious liability depends upon the answers to two questions. First, what sort of relationship has to exist between an individual and a defendant before the defendant can be made vicariously liable in tort for the conduct of that individual? Secondly, in what manner does the conduct of that individual have to be related to that relationship in order for vicarious liability to be imposed? The present appeal, like the case of Cox, is concerned only with the first of those questions. In her article ‘Vicarious liability in the UK Supreme Court’ (2016) in UK Supreme Court Yearbook (Vol. 7, pp.152–166) Professor Paula Giliker comments: ‘One is left to wonder where, after three Supreme Court decisions in four years, this leaves the legal development of the doctrine of vicarious liability’. In Armes the Supreme Court was being asked to develop the law beyond the point which it had already reached (and disagree with the conclusions reached in the courts below).The majority ruling in favour of vicarious liability (Lord Hughes dissented) endorses Giliker’s prediction that: ‘Cox and Mohamud are far from the end of this story’. Various Claimants v Morrison Supermarkets plc [2018] EWCA Civ 2339 - In pursuit of a personal grievance, a senior internal IT auditor at Morrison downloaded the personal details of some 100,000 other employees and shared them, including to three national newspapers. He was sentenced to eight years’ imprisonment for fraud and statutory offences. Some 5,000 of the victims brought an action against their employer as vicariously liable for breach of the Data Protection Act 1998, breach of confidence and misuse of private information. The Court of Appeal upheld the trial judge’s finding of vicarious liability. The first issue for the Court was whether these particular torts were within the ambit of vicarious liability. This was answered in the affirmative. Secondly, had the employee been acting in the course of employment? Again the answer was yes, despite the fact that the tortfeasor’s actions had been directed specifically against his employer and fellow employees. The two tests from Mohamud were applied: deriving from the function the worker was employed to perform, there was a ‘seamless and continuous sequence of events’, even though the ultimate act of sharing the information took place at the weekend when he was at home. Be aware that an appeal to the Supreme Court is likely.

- 6. LAWOF TORT Mrs. Ari Bahmini LLB (Univ of London), CLP (Mal) 34 Bellman v Northampton Recruitment Ltd [2018] EWCA Civ 2214 - In a case perhaps less contentious than above, the generous judicial trend in vicarious liability persisted in the case of an after-party following the annual Christmas get-together. Here, after consuming considerable amounts of liquid ‘seasonal cheer’, the managing director got into an argument over a workplace issue and ended up punching his employee who suffered serious brain damage and brought an action based on vicarious liability. Overturning a first-instance decision in favour of the defendants, Lady Justice Arden examined the overall context. Although the attack took place at a different venue than the official office party, there was a ‘sufficient connection’ between the wrongdoer’s position as the most senior employee in the company and the nature of the dispute to render the assault as being within the course of employment. On vicarious liability for violence by one employee to another: Weddall v Barchester Healthcare Ltd [2012] - In the first case, Mr Weddall was the deputy manager of a care home run by Barchester Healthcare Ltd (Barchester). Mr Marsh also worked at the care home as a senior health assistant. Mr Weddall and Mr Marsh were not on good terms. One evening, a night-shift employee called in sick. As part of his duty to find a replacement, Mr Weddall called Mr Marsh to see whether or not he wanted to work the extra shift. Mr Marsh refused the voluntary extra shift. However, Mr Marsh, who was drunk when he received the telephone call, did not react well to the call. Shortly after, he rode his bicycle to the care home and violently attacked Mr Weddall without provocation. Wallbank v Wallbank Fox Design Ltd [2012] - The Court of Appeal applied the broad and flexible test for vicarious liability established in Lister and others v Hesley Hall Ltd [2001] IRLR 472 HL. In the case of wrongdoing by employees, this test of whether or not an employee’s wrongful act was committed in the course of his or her employment, turns on the closeness of the connection between the wrongful act and the employment. The Court of Appeal said that each case must be determined by reference to its own facts. The Court of Appeal observed that each of these cases relates to an employee’s violent response to a lawful instruction. The Court of Appeal dismissed the appeal in Weddall and allowed the appeal in Wallbank. Employers and Independent Contractors - As a general rule, there is no vicarious liability on the part of the "employer" for the torts of his independent contractor. However, there are exceptions to this general rule where a person can be liable: If there is a failure to ensure the independent contractor is reasonably competent and carried out reasonable supervision; or Where the independent contractor is hired to do an act, which involves a high risk of creating a tort. Principal and Agent - It is possible for a principal to be vicariously liable for the tort of his agent where the agent commits a tort in the course of his employment. Ormrod v Crossville Motor Services (1953) - The owner of a car asked a friend to drive the car to Monte Carlo from Birkenhead. The owner planned to compete in a car rally in Monte Carlo and the two were to go on holiday together afterwards. The friend caused damage to the P’s bus in an accident caused by his negligence. HELD: The owner was liable for his friend’s negligence, even though the friend was going on the journey partly for his own purposes. Morgans v Launchbury (1973) - A husband sometimes used his wife’s car. The wife was concerned about the husband’s drinking habits and said he had to get a friend to drive him home if he had too much to drink. The husband did this and the friend negligently caused an accident. An action was brought against the wife, claiming she was vicariously liable. HELD: The husband was using the car for his own purposes and not hers. The driver was therefore not an agent of the wife.

- 7. LAWOF TORT Mrs. Ari Bahmini LLB (Univ of London), CLP (Mal) 35 NERVOUS SHOCK ELEMENTS UNDER NERVOUS SHOCK PRE – CONDITION OF RECOVERY IN NERVOUS SHOCK: “RECOGNISABLE PSYCHIATRIC INJURY” Brice v Brown (1901) - hysterical personality disorder Hinz v Berry (1970) - morbid depression Page v Smith (1996) - myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) or chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) Vernon v Bosley (1997) - pathological grief disorder (PGD) White v Chief Constable of South Yorkshire Police (1999) - post – traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) NON-RECOGNISABLE FORM OF INJURY Reilly v Merseyside HA (1995) 6 Med LR 246 CA - Elderly visitors PP suffering from angina and claustrophobia respectively were stuck for over an hour in a hospital lift that jammed because of negligent maintenance. Allowing DD's appeal, the Court of Appeal said PP's worry about one another, and even panic, were normal human emotions in the face of a most unpleasant experience. They were not recognisable psychiatric injuries, so the claim must fail. Fraser v State Hospitals (2000) - FACTS: A former psychiatric nurse sought damages for the effects of various incidents in the course of his work in a secure hospital. HELD: Rejecting his claim, the judge said there is no duty to protect an employee from unpleasant emotions such as grief, anger and resentment or normal human conditions such as anxiety or stress (not recognisable psychiatric illness). THE 3 ELEMENTS UNDER NERVOUS SHOCK DUTY OF CARE 1. Who Is The P? P = Primary victim The leading case on primary victims is Page v Smith (1995) HOL. The importance of the distinction between primary victim and secondary victim (refer to the next category of P) was also stated in the case of Page v Smith (1995). Page v Smith (1995) - FACTS: P, who was involved in a car crash caused by the D’s negligence, suffered no physical injury. However, the accident revived a condition of myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) or chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), from which he had suffered before for about 20 years, but which was in remission at the time of the accident. He was unlikely to work again. He sued the D for damages for permanent CFS. HELD: On appeal to the HOL, P was entitled to recover because: 1. In nervous shock cases, a distinction is to be drawn between the primary & secondary victim. For primary victim, it is only necessary to show that the D should have foreseen some form of personal injury, physical or psychiatric i.e. also general negligence test. It is not necessary to show that the nervous shock itself must be reasonably foreseeable in order to recover for shock, even though no physical damage occurred. 2. Since the D should have foreseen some form of personal injury to the P and owed him a duty of care, it did not matter that the P was predisposed to psychiatric illness or that it was unusually severe. The D must take his victim as he finds him. Therefore, today after the case of Page v Smith (1995), the test of duty of care for primary victims in nervous shock is the general negligence test i.e. the 3-stage test in Caparo v Dickman (1990) – proximity, foreseeability & fair, just and reasonable. The decision in Page v Smith (1995) – HOL was applied in the case of Young v Charles Church (Southern) Ltd (1997) – CA. FACTS: P, a construction worker, suffered psychiatric illness after witnessing the death of his colleague from a distance of some 6 to 10 feet. His colleague was killed instantly when a scaffold pole, which the P had just handed to his colleague, brushed against a live overhead electric power line. Another colleague standing nearby also suffered burns. P’s psychiatric illness was caused by the impact upon him of the dreadful injuries and death of his colleague (unlike the car driven in Page v Smith). HELD: The distinction between Page v Smith was not significant. The P was at risk of physical injury from an accident, which could be foreseen, and his illness was caused by the accident, which did not occur as a result of the D’s negligence. Therefore, the P was primary victim under the Page v Smith test.

- 8. LAWOF TORT Mrs. Ari Bahmini LLB (Univ of London), CLP (Mal) 36 However the case of Page v Smith (1995) has been criticised but reaffirmed by the House of Lords: Simmons v British Steel plc [2004] UKHL 20: 2004 SLT 595. Facts: D, the steel company that employed C. C fell and hit his head at work. He suffered depression and a pre-existing skin disease flared up, not because of the original injury “but from his anger at the happening of the accident” (lack of apology or support following the accident, and failing to prevent the accident when warned of the danger). Held: C was entitled to compensation for the consequences of the accident and not just for the physical injuries. C’s anger was neither de minims nor an intervening act. C was “a primary victim” according to the classification in Page v Smith (1996). A wrongdoer takes his victim as he finds him Smith v Leech Brain & Co Ltd [1962] CA. Home Office v Butchart [2006] EWCA Civ 239 - Facts: A prisoner B suffered psychiatric injury following the suicide (which he claimed had been foreseeable) of his cell-mate, and sued the prison authorities. Upholding the judge's refusal to strike out the claim before trial, Latham LJ said the Hillsborough control mechanisms below (including "close ties of love and affection") are not meant to apply in all cases of psychiatric injury. B was a prisoner in custody, and the prison authorities owed him a duty to take reasonable steps to minimise the risk of foreseeable psychiatric harm to him. Held: A person who was (or believed herself to be) at risk of physical injury is also regarded as a primary victim and can claim for her psychiatric injury even if she does not actually suffer physical harm. French v Chief Constable of Sussex Police [2006] EWCA Civ 312 - The Court of Appeal held that claims by police officers for psychiatric injuries allegedly suffered as a result of a fatal shooting, which they had not witnessed, and which had led to criminal and disciplinary proceedings against them that had led to stress and the injuries complained of, were struck out on the basis that they were bound to fail on grounds of causation and remoteness. MacLennan v Hartford Europe Ltd [2012] EWHC 346 HC - The High Court has held that an employer was not liable for a HR professional’s chronic fatigue syndrome because the employee’s illness was not caused by her work. 2. Who Is The P? P = Secondary victim Owens v Liverpool Corporation [1938] 4 All ER 727 - CA - A coffin was overturned when the hearse was struck by a negligently driven tram. Relatives who had seen the incident or its immediate results claimed damages for psychiatric injuries suffered as a result, but the judge dismissed their case because there had been no injury or apprehension of injury to any human being. Allowing their appeal, the Court of Appeal said the right to recover damages extends to every case where injury by reason of mental shock results from the negligent act of the defendant. [This decision was doubted by the House of Lords in Bourhill v Young, but not directly overruled]. Bourhill v Young [1942] 2 All ER 396 - HL - A careless motor-cyclist collided with a car and was killed. P, getting off a tram 20 yards away, heard the collision and later saw the blood on the road; she suffered psychiatric injury and her baby was stillborn. On the facts of the case this damage was not foreseeable, and the motor-cyclist had no duty of care to such a bystander. However, the House conceded that there was a "shock area" (greater than the area of foreseeable physical damage) in which it might be foreseeable that psychiatric injury would be suffered by a reasonably strong-nerved person witnessing the event. Hinz v Berry [1970] 1 All ER 1074 - CA - A mother suffered psychiatric shock on seeing her husband and children seriously injured in a road accident, just across the road from where she was. Affirming the trial judge's award of damages for this inter alia, Lord Denning MR said obiter that a line must be drawn between sorrow and grief (for which damages are not recoverable) and psychiatric illness (for which they are).

- 9. LAWOF TORT Mrs. Ari Bahmini LLB (Univ of London), CLP (Mal) 37 In the case of McLoughlin v O’Brian (1981) HOL, the courts were prepared to extend liability to a situation in which P only saw her family after they had been removed from the scene of the event to a hospital casualty department. Here the mother saw members of her family in hospital shortly after a fatal road accident; one daughter was dead and her husband and two other children were seriously injured. She suffered psychiatric illness and succeeded in a claim against the negligent driver: her relationship with the primary victims was as close as it could be. Therefore, for a secondary victim to recover in nervous shock, he/she must satisfy the test of duty of care which was established by Lord Wilberforce & Lord Edmund-Davies in McLoughlin v O’Brian (1983) as applied in Alcock v Chief Constable of South Yorkshire (1991) – HOL. Alcock v Chief Constable of South Yorkshire (1991) – HOL (Leading Judge: Lord Keith) - FACTS: This case arose out of the Hillsborough Stadium tragedy in 1989 in which 95 persons were crashed to death during a football match (FA Cup semi-final between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest at Hillsborough Stadium in Sheffield). The match was a sell-out and television cameras were at the ground to record the football for transmission later that evening. The Ps were relatives and friends of the primary victims who claimed they suffered nervous shock as a result of watching the telecast or been at the stadium. The Ds (the Chief Constable of the police force responsible for policing the ground) admitted that it was their negligence, which caused the incident. HELD: The HOL rejected their claim and made it clear that in nervous shock cases, it was Lord Wilberforce & Lord Edmund Davies’ test in McLoughlin v O’Brian (1983), which must be applied. The court went on to explain the 3 elements, which a secondary victim in nervous shock needed to satisfy: (a) Close relationship between the P and the person suffering injury (immediate victim) o The P must establish a close tie of love and affection to the immediate victim. o The HOL came to a conclusion that it is not only those with a parent-child or husband-wife or possibly fiancée relationship who can claim. o Those with more remote relationship i.e. distant relatives and friends, may also claim provided it can be shown that their relationship is so close and intimate that their love and affection for the victim is comparable to that of the normal spouse, parent or child. o Lord Oliver stated that creating a list of categories will amount to great injustice. (b) The P had to be proximate to the accident in terms of time and space or its immediate aftermath P must be close to the accident in both time and space. There is no need for the P to be present at the scene of the accident but it also include “immediate aftermath.” In McLoughlin v O’Brian (1983), P only arrived at the hospital an hour or so after the accident in which her husband and 3 children were involved. There was sufficient proximity i.e. immediate aftermath. Lord Wilberforce said that it would be impractical and unjust to insist direct and immediate sight or hearing and to exclude a P who comes very soon upon the scene. In Alcock, an attempt by the Ps to extend the concept beyond the aftermath failed. Several P’s, who had not been present at the ground when tragedy occurred, went there subsequently in order to identify the bodies of relatives. The earliest such P’s arrived at the scene between 8 and 9 hours after the accident, as opposed to an hour or so after the accident that Mrs. McLoughlin had arrived at the hospital. Lord Ackner thought that, the identification process might correctly be described as “part of the aftermath”, but it was not “part of the immediate aftermath.” Furthermore, there was no proximity for several Ps who had watched the disaster unfold on the live broadcast. This was because broadcasting guidelines were followed and no actual sufferings were shown.

- 10. LAWOF TORT Mrs. Ari Bahmini LLB (Univ of London), CLP (Mal) 38 (c) P must suffer nervous shock as a result of seeing or hearing the accident or it is immediate aftermath through his/her own unaided senses The psychiatric illness must be shown to result from the trauma of the event of its immediate aftermath. Psychiatric illness resulting from being informed of a loved one’s death by 3rd parties (including newspapers or broadcast reports), however grisly the circumstances, is not recoverable. For e.g. if a young child is crushed by falling bricks at school, and within an hour, her mother comes to her deathbed at the hospital, the mother may recover from the trauma of coming upon the immediate aftermath of the accident. But if the child’s father has a heart attack when told of the girl’s fate, his loss remains irrecoverable. If his illness were sudden by identifying his daughter at the mortuary next day, it is still irrecoverable. Their Lordships refused to extend psychiatric harm indefinitely. In Alcock, several Ps who had watched the disaster unfold on live broadcast not amounted to seeing/hearing in this sense because due to the broadcasting guidelines were followed and no actual sufferings of identifiable individuals were showed. However in Alcock, the HOL did not altogether rule out the possibility of liability where the psychiatric injury was induced by contemporaneous television transmission of the incident. Two HOL judges gave an example whereby live telecast of the accident may be able to amount to “proximity”. For e.g. live television broadcast of a special event in which children were traveling in a hot air balloon, watched by parents, in which it suddenly burst into flames. The impact of such simultaneous television pictures might be as great, if not greater, as actual sight of the accident. In practice, element (b) & (c) are closely related. Normally P who fails on the 2nd element will not be able to satisfy the 3rd element. Taylorson v Shieldness Produce [1994] PIQR 329 CA - PP were the parents of a 14-year-old boy crushed in a road accident. They were informed of the accident shortly after it happened, and caught a glimpse of their son as he was being transferred between hospitals, but were not allowed to see him during treatment. The father saw his son in hospital that evening; the mother saw him next day, and they were with him for the next two days until his life support machine was switched off. The Court of Appeal said PP fell outside the "immediate aftermath" test; they had suffered from grief at their son's death rather than shock at the traumatic events causing his injuries. Sion v Hampstead Health Authority (1994) 5 Med LR 170 CA - A 23-year-old man was badly injured in a road accident, and his father P was at his hospital bedside until he died two weeks later, allegedly because of negligent treatment by the hospital. P claimed damages for his own psychiatric injuries, but the judge struck out his claim and his appeal failed: there was no "sudden awareness" of a horrific event foreseeably giving rise to P's shock. Tredget v Bexley HA (1994) 5 Med LR 178, Judge White - CC were the parents of a child who was born asphyxiated and died 48 hours later as a result of the hospital's negligence. They each suffered a pathological grief reaction, and the judge allowed their claim for damages against the hospital even though the death had been gradual rather than sudden. Vernon v Bosley (No1) (1997) – CA - FACTS: The P’s 2 young children were passengers in a car driven by their nanny, the D, when it veered off the road and crashed into a river. The P did not witness the original accident, but was called to the scene immediately afterwards and watched unsuccessful attempts to salvage the car and rescue his children. These efforts failed and the children drowned. The P became mentally ill and his business and his marriage both failed. The D accepted that his illness resulted from the tragic deaths of his children but contended that his illness was caused not by the shock of what he experienced at the riverside, but by pathological grief at the loss of his family resulting in an illness called pathological grief disorder (PGD not PTSD). HELD: Although damages for ordinary grief and bereavement remain irrecoverable, a secondary victim was entitled to recover damages for psychiatric illness where he could establish that he met the general pre-conditions for such a claim, that is a close relationship with the primary victim and proximity to the accident, and that the negligence of the D caused or contributed to his mental illness. The P could recover compensation regardless of whether in part his illness consisted of an abnormal grief reaction as much as post traumatic stress disorder. Note: This decision does not mean that every person who loses a loved one and becomes ill through grief can sue the D who is responsible for the death of the primary victim. Should a child die in a car crash in Cornwall and the news of her death, the misery of her loss, result in her grandmother in Newcastle becoming ill, no claim will lie. The grandmother cannot establish the requisite conditions limiting any claim by secondary victims. AB v Tameside and Glossop Health Authority [1997] - Facts: Claimant was sent a letter that they were exposed to the HIV virus, they argued they should have told them face to face. Held: No duty is owed.

- 11. LAWOF TORT Mrs. Ari Bahmini LLB (Univ of London), CLP (Mal) 39 Palmer v Tees [2000] - Facts: Mother, of a 4 year old who was murdered and found a few days later by the mother until then she suffered psychiatric illness. Held: That no duty of care was owed, she didn’t see the body, no aftermath, her illness was created by her worries etc. Greatorex v Greatorex [2000] 1 WLR 1976 - First Defendant had been drinking with a friend, who is the Defendant in the proceedings. The First Defendant was driving a car belonging to the Defendant, who had given him permission to drive the car and was a passenger in it. Whilst overtaking on a blind brow the First Defendant negligently drove over on the wrong side of the road and was hit by an oncoming vehicle. The Defendant was uninjured. The First Defendants head was injured and he was unconscious for about an hour. Initially he was trapped inside the car. The police, ambulance and fire services attended the scene of the accident. Among the fire officers who attended the scene was the First Defendants father, the Claimant. At the time of the accident he was employed as a Leading Fire Officer. He was nowhere near the scene of the accident when it happened. He went there in the course of his employment. Having been informed that his son has been injured, he attended to him. The Claimant was later diagnosed as suffering long-term post traumatic stress disorder as a result of the accident. The First Defendant was subsequently convicted of driving a motor vehicle without due care and attention, driving without insurance, and failing to provide a specimen. Held: (1) A primary victim does not owe a duty of care to a third party in circumstances where his self-inflicted injuries caused the third party psychiatric injury. (2) On the agreed facts the First Defendant did not owe the Claimant a duty of care not to harm himself. (3) On the agreed facts the First Defendant did not owe the Claimant a duty of care not to cause him Psychiatric Injury as a result of exposing him to the sight of the First Defendant’s self- inflicted injuries. Boylan v Keegan (2001) unreported - An 8-year-old girl was badly injured in a road accident; her mother was at the scene and used a mobile phone to contact the father, who thus heard the screams and the ambulance sirens as they occurred. The girl died in her father's arms two days later, the driver was imprisoned for dangerous driving, and the father claimed inter alia for his own psychiatric injury. Judge Tim King said his claim must fail: he was not present in the immediate aftermath, and he had not seen or heard the accident with his own unaided senses. However, in November 2001 the Criminal Injuries Compensation Authority announced that it would pay compensation up to £20 000 to close relatives of those killed in the terrorist attack on the World Trade Centre, who suffered psychiatric injury through watching the events of 11 September on live television. Evidence of a specific psychiatric illness would still be required, as would "close ties of love and affection", and those who merely saw news footage later would not be eligible, but presence through the medium of live television would be sufficient. Ex gratia payments of this sort cannot establish a binding precedent, of course, but may point the way to a development of the current rules. This is consistent with a recommendation of the Law Commission, who proposed in February 1998 (Law Commission Report No.249) an extension to the existing law. They recommended keeping the requirement for "close ties of love and affection", but extending the list of relationships in which such ties are presumed to include siblings and long-term cohabitants. They also proposed abolishing the requirement of proximity of time and space, and the "own unaided senses" rule, where those close ties can be shown, and removing any requirement for a single shocking event to allow (for example) claims by those who suffer psychiatric injury from watching a negligently injured loved one die slowly. It remains to be seen whether this report will ever be incorporated in legislation. North Glanmorgan NHST v Walters [2003] PIQR P34, CA - FACTS: A 10-month-old baby was taken to hospital suffering from jaundice, and the hospital negligently under-estimated the seriousness of his condition. Very early next morning the baby's mother (who was sleeping in the same room at the hospital) woke to find the baby having a fit. Doctors assured her the child would recover, and he was sent to London by ambulance, but on arrival he was found to have suffered irreversible brain damage. The following day, the baby's parents agreed that life support should be withdrawn, and the baby died in its mother's arms. The mother suffered a "pathological grief reaction", and the judge awarded damages on the basis of a 36-hour-long "shocking event". D appealed. HELD: Dismissing the hospital's appeal, Ward LJ said the judge had rightly taken into account the doctors' statements to the mother during this period: they were part of the circumstances and were not merely "being informed of the accident". Atkinson v Seghal (2003) - The Court of Appeal said the "immediate aftermath" should run to the end of C's visit to the mortuary since all the time C was showing signs of an abnormally strong grief reaction.

- 12. LAWOF TORT Mrs. Ari Bahmini LLB (Univ of London), CLP (Mal) 40 3. Who Is The P? P = Rescuer McFarlane v E.E. Caledonia Ltd. (1994) – CA made it clear that a mere bystander can never claim in nervous shock no matter how horrific the accident. However, there is an exception where bystander can claim in nervous shock. The exception is if the bystander is a rescuer. Chadwick v British Railways Board [1967] 1 WLR 912 - This case arose from a horrific train crash in Lewisham in which 90 people were killed and many more were seriously injured. Mr Chadwick lived 200 yards from the scene of the crash and attended the scene to provide some assistance. He worked many hours through the night crawling beneath the wreckage bringing aid and comfort to the trapped victims. As a result of what he had witnesses he suffered acute anxiety neurosis and received treatment as an inpatient for 6 months. Held: His estate was entitled to recover. The defendant owed Mr Chadwick a duty of care since it was reasonably foreseeable that somebody might try to rescue the passengers and suffer injury in the process. Waller J quoted Cardozo J in Wagner v International Railway Company 232 NY Rep 176, 180 (1921): “Danger invites rescue. The cry of distress is the summons to relief. The law does not ignore these reactions of the mind in tracing conduct to its consequences. It recognises them as normal. It places their effect within the range of the natural and probable. The wrong that imperils life is a wrong to the imperilled victim; it is a wrong also to his rescuer. Note: A person who has been trained to provide emergency services cannot fall under the definition of rescuers – White & Others v Chief Constable of South Yorkshire (1998) – HOL. 4. Who Is The P? P = Who witnessed his/her property being damaged by the D’s negligent act Attia v British Gas (1987) - FACTS: The P came home and found her house on fire. The fire was caused by the D’s negligence. The P claimed she suffered nervous shock. HELD: The P succeeded on the application of reasonable foresight alone i.e. P can claim provided a reasonable man would suffer nervous shock under the circumstances. 5. Who Is The P? P = An involuntary participant This is a situation whereby the negligent act of the D has put the P in the position of being, or of thinking that he is about to be or has been, the involuntary cause of another’s death or injury and the illness complained of stems from the shock to the P of the consciousness of this fact. The test for duty of care is similar to primarily victim i.e. the 3-stage test in Caparo v Dickman. Hunter v British Coal Corporation & Another (1998) – CA - FACTS: P was employed by the 2nd D as the driver of a diesel-powered vehicle at the 1st D’s coal mine. Concerning that the vehicle would get stuck in the mud, the P attempted to close up the hydrant valve with the help of fellow employee, C, but was unable to do so. He went off in search of a hose pipe to channel the escaping water onto the conveyor. When he was 30 meters away, the hydrant burst and he rushed to find a stop valve to shut the water off. He managed to do it after 10 minutes. Whilst doing so, he heard a message that a man had been injured and on his way back to the scene of the accident, he met a workmate who told him that it looked like C was dead. P immediately thought that he was responsible and suffered nervous shock and depression as a consequence. He, thereafter, brought proceedings against the Ds for damage for psychiatric injury. HELD: P, who believed that he had been the involuntary cause of another’s death or injury in an accident caused by the D’s negligence could recover damages as a primary victim for psychiatric injury suffered as a result if he had been directly involved as an actor in the accident. However, the P who was not present at the scene of an accident could not recover damages as a primary victim for such an injury because he felt responsible for the accident when the news of it was broken to him later. Applying to current facts, P was not involved as an actor in the accident in which C died, as he was 30 meters away when the hydrant burst and he only suffered his psychiatric injury on being told of C’s death 15 minutes later and because he felt responsible for it.

- 13. LAWOF TORT Mrs. Ari Bahmini LLB (Univ of London), CLP (Mal) 41 Assumption of responsibility: close relationship There remain a number of isolated cases with (as yet) no clear principles. Should a defendant be liable for causing psychiatric injury by carelessly passing on wrong information, or by passing on correct information in a carelessly insensitive way? There may emerge a principle that a defendant should be liable if there is an assumption of responsibility to protect the claimant against psychiatric injury or if there is an ongoing relationship between the parties that entails such a responsibility. W v Essex County Council [2001] 2 AC 592; A v Essex County Council [2003] EWCA Civ 1840: [2004] 1 WLR 1881; AB v Tameside and Glossop Health Authority [1997] 8 MedLR 91; Leach v Chief Constable of Gloucestershire Constabulary [1999] 1 All ER 215 and McLaughlin v Jones [2002] 2 WLR 1279. In the W v Essex County Council [2001] 2 AC 592 case Lord Slynn suggested that the primary and secondary victim categories could not accommodate all cases. The House of Lords refused to strike out a claim (in other words the claim was held to be arguable) by parents to whom a local council, in breach of an undertaking, sent as a foster child a known sexual abuser. The child then abused the other children in the family causing psychiatric injury to the parents. They had some of the characteristics of secondary victims, except that they did not see the abuse taking place. On the other hand, unlike most secondary victim cases, there had been an ongoing relationship between the council and the parents as to their suitability as foster parents. See also D v East Berkshire Community NHS Trust [2005] UKHL 23: [2005] 2 WLR 993. BREACH OF DUTY If the question already stated that there is a clear breach of duty on the part of the D, for e.g.; “D has admitted their negligence”, then there is no need to discuss the element of breach in detail. It is sufficient by stating, “Since the D had admitted negligence, the D has breached his duty of care.” CAUSATION OR DAMAGE Under this element P must satisfy both the causation in fact and causation in law. Johnston v NEI; Grieves v Everard [2007] UKHL 39 - In several conjoined appeals, the House of Lords (affirming the Court of Appeal) rejected claims against their employers by workers who had developed pleural plaques as a result of their exposure to asbestos dust. These plaques show the presence of asbestos in the lungs, and that asbestos may lead to serious lung diseases: the diagnosis of pleural plaques thus causes understandable anxiety. But neither pleural plaques (which are themselves harmless), nor the risk of contracting some future disease, nor anxiety falling short of psychological illness, constitutes damage of a kind recognised by the law of negligence. One claimant G had suffered depressive illness arising from his anxiety, but the right to protection against psychiatric illness is limited and does not extend to an illness suffered only by an unusually vulnerable person because of apprehension that he may suffer a tortious injury. The risk of future disease is not actionable and neither is a psychiatric illness caused by contemplation of that risk.

- 14. LAWOF TORT Mrs. Ari Bahmini LLB (Univ of London), CLP (Mal) 42 RULE IN WILKINSON V DOWNTON 1. A willful act (or statement) of the D, calculated to cause physical harm to the P and in fact causing physical harm to him, is a tort. 2. The main element of the rule in Wilkinson v Downton is where some physical harm is intentionally inflicted by indirect means. This was established by Wright J in Wilkinson v Downton (1897). Wilkinson v Downton (1897) - As a practical joker, D told P, a married woman, that her husband had met with an accident and had broken both his legs. P believed D’s statement and suffered nervous shock. HELD: The D was liable in tort i.e. trespass to person; as he did an act which was calculated to cause harm and has actually caused harm to the P. 3. The principle in Wilkinson v Downton was approved and applied by CA on somewhat similar facts in Janvier v Sweeney (1919) – CA. FACTS: D was a private detective. In order get papers from the P, D falsely represented that he was a police officer and that P was in danger of arrest for association with German spy if she refused to co-operate with him. P suffered psychiatric trauma. HELD: D was liable under the rule in Wilkinson v Downton. 4. This tort of the rule in Wilkinson v Downton is to fill the gaps in the trespass torts. Because of the rule that intentional acts, which indirectly cause harm, are not trespasses, there are many situations where but for the judgment in Wilkinson v Downton, there might be no action. For examples; putting poison in another’s tea, digging a pit into which it is intended that another shall fall or scare a person into nervous shock by dressing up as a ghost. These are not trespasses as the harm was indirectly caused by D’s act. These could not fall under negligence because D had done the act intentionally. Therefore, these should properly be regarded as intentional physical harms within the principle of Wilkinson v Downton. 5. The nature of the mental element required for this form of liability i.e. whether D must also have the intention to cause harm or even realized that it might occur; is not very clear. However, the test seems to be, ”Whether the D has deliberately engaged in conduct whereby the harm is sufficiently likely to result that the D cannot be heard to say that he did not mean to do so.” 6. It should be noted that the principle in Wilkinson v Downton is not only confined to harm arising from statement. It is also extend to harm arising from act for example; intentional infection of another person with disease. Furthermore, the harm caused to P is not only confined to nervous shock but it also covers physical injury and damage to property. (NOTE: This principle does not cover economic loss, as the claim will fall under another area of tort i.e. intentional infliction of economic harm). 7. Another difference between trespass to person and the rule in Wilkinson v Downton, other than the act of indirectness, is the element of harm or damage. In other words, in order for the rule in Wilkinson v Downton to apply, the intentional act of D must cause P to suffer actual harm or damage. wilkinson V downton CARIOUS LIABILITY

- 15. LAWOF TORT Mrs. Ari Bahmini LLB (Univ of London), CLP (Mal) 43 OPO (a child by BHM his litigation friend) v MLA [2014] EWCA Civ 1277 Court of Appeal (Arden, Jackson & McFarlane LJJ) MLA was a performing artist. OPO was a child and the son of MLA and BHM, his litigation friend. STL was a commercial publisher. The father had written a semi-autobiographical book for publication in the UK and other jurisdictions. The book gave an account of the serious childhood sexual abuse suffered by the father over many years. He was traumatised by this, as well as suffering physically, and it has led him to have episodes of severe mental illness and incidents of self-harming. The book was dedicated to his son. The son was born in the UK, but since his parents’ divorce now lives in another country with his mother. He suffers from significant disabilities: he has a diagnosis of a combination of ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder), Asperger’s syndrome, Dysgraphia and Dyspraxia. Evidence of two child psychologists suggested that the child would be at risk of serious psychological harm if he were exposed to the accounts given by the father in the book. The most recent report concluded that the book would be likely to exert a catastrophic effect on the child’s self-esteem and to cause him enduring psychological harm. That evidence was disputed by the father. The child applied for an injunction to Bean J. He contended that publication of the book should be restrained on three bases: (1) that publication would represent misuse of private information; (2) that it would be a breach of the duty of care owed by the father to his son; and (3) that publication would amount to the deliberate infliction of emotional harm under the tort recognised in Wilkinson v Downton [1897] QB 57. The father and the publisher opposed the application, contending that none of the causes of action had any prospect of success; alternatively that the Claimant’s prospects of success were not sufficiently favourable to justify the grant of an injunction in accordance with s.12 Human Rights Act 1998 and that, in any event, the law that applied to any cause of action that the claimant could establish would be that of the country in which he lived not the UK. In a reserved judgment handed down in private, Bean J refused the injunction, holding that all three causes of action had no prospects of success. He therefore dismissed the application for an injunction and dismissed the entire claim. In light of his findings, he did not determine the issue of choice of law. Permission to appeal was refused by the Judge, but granted by the Court of Appeal. The Claimant appealed. Issue (1) Did the Claimant have a viable cause of action? (2) If so, should English law be applied or that of the country where the child lived? (3) Should any injunction be granted, having regard to s.12 Human Rights Act 1998?

- 16. LAWOF TORT Mrs. Ari Bahmini LLB (Univ of London), CLP (Mal) 44 Held: Allowing the appeal and granting an injunction to restrain publication, with a public domain provision: (1) No claim could be brought for misuse of private information. The tort was only engaged by publication of information that related to the claimant. The book, although it featured the child prominently, did not threaten to misuse any of his private information. The information that was said to be likely to cause harm to the child all related to his father. Nor could a claim in negligence be maintained. Although there was a sufficient relationship of proximity between the son and father and the damage was foreseeable, the Court of Appeal held that it would not be fair, just or reasonable to impose a duty of care on a parent towards his child. However, the elements of the tort of Wilkinson v Downton were sufficiently made out. Liability for the tort is incurred if a defendant wilfully does an act calculated to cause psychiatric harm. Intention could be imputed to a defendant who disclaimed the intention to cause the relevant harm if that harm was likely to be caused and he carried on to do the relevant act. Although the father considered publication a responsible act he could not be heard to say that he did not intend the book to reach the child: the book was dedicated to him and parts of it were directed to him. The father had specifically recognised the vulnerability of the child to risk of harm caused by his learning of matters concerning his father’s past. (2) English law would be applied. At the interim stage, the test was whether the child could show that the proposed publication of the book would be unlawful under the applicable law. The question of choice of law had to be determined in accordance with the Rome II Regulation, particularly Articles 4(1) and (3). Article 4(1) provided that the normal rule would be that the proper law would be the country in which the damage would occur. In terms of the Wilkinson v Downton tort that would be the country where the child lived. However, under Article 4(3) that usual rule could be displaced where it was “clear from all the circumstances of the case that the tort is manifestly more closely connected with a country other than that indicated by Article 4(1)”. (3) An injunction would be granted. Under s.12 Human Rights Act 1998, the child had demonstrated sufficiently favourable prospects on the facts of establishing at trial that his claim under Wilkinson v Downton would be successful so as to justify the grant of an injunction pending trial. Cream Holdings v Banerjee [2005] 1 AC 253 applied. This was a case in which the Court is justified in applying a lower standard than more likely than not given the risk of serious harm to the child if the injunction were not granted. HUMAN RIGHTS Wainwright v United Kingdom (2007) 44 EHRR 40 FACTS: The Applicants, a mother and her handicapped son Alan, attended HMP Leeds to visit another son Patrick who was being held on remand. The Governor had given an order that all Patrick's visitors were to be strip-searched as he was suspected of using drugs. The Applicants were separated and told that if they did not agree to the search they would be denied their visit. They reluctantly agreed. They were not asked to sign consent forms until after the searches were complete. Various breaches of procedure took place including the touching of Alan's genitals. Mrs Wainwright was severely distressed as a result of the strip search and Alan, who suffers from cerebral palsy and had a mental age of 12 at the time, suffered PTSD. HELD: The European Court of Human Rights held that the treatment of Mrs Wainwright and her son, who were intentionally caused nervous shock. 1. The treatment to which the Applicants had been subjected was negligent and fell short of the level of severity necessary to constitute a breach of Article 3. 2. However, Article 8 also protects physical and moral integrity. As the searches had not been proportionate to the aim of preventing crime and disorder in the manner in which they had been carried out, there was a violation of Article 8. 3. The absence of an effective domestic remedy, in particular the absence of a general tort of invasion of privacy, resulted in a breach of Article 13. 4. The applicants were awarded 3,000 Euros each in damages for the distress caused to them.

- 17. LAWOF TORT Mrs. Ari Bahmini LLB (Univ of London), CLP (Mal) 45 Since liability was thought to be unsatisfactory, complex and confusing to protect visitors on premises, the Law Reform Committee was set up in 1952 and that caused Parliament to enact the OCCUPIERS’ LIABILITY ACT 1957. At that time occupiers owed only a very limited duty to people who were not lawful visitors (usually but slightly inaccurately called trespassers). A common law duty did develop in the years following 1957, but it was in turn replaced by a statutory duty in the Occupiers’ Liability Act 1984. Although occupier’s liability is governed by Occupiers’ Liability Act 1957 & Occupiers’ Liability Act 1984 in this modern law, nevertheless certain previous common law rules still apply. Scope of Occupiers’ Liability Act 1957 Does the Act apply only to injuries resulting from the state of the premises or does it also apply to injuries resulting from activities on the premises? Injury suffered on the premises which is not caused by the condition of the premises, but, for instance, by a negligently driven car, is said to result from the ‘activity’ duty. Slater v Clay Cross Co [1956] 2 QB 264 - Lord Denning said if a landowner is driving his car down his private drive and meets someone lawfully walking upon it, then he is under a duty to take reasonable care so as not to injure the walker; and his duty is the same no matter whether it is his gardener coming up with plants, a tradesman delivering goods, a friend coming to tea, or a flag seller seeking a charitable gift. Duty The duty of occupiers to their lawful visitors is clearly set out in S2 (1) which states: - An occupier of premises owes the same duty, the common duty of care to all his visitors except insofar as he is free to and does extend, restrict, modify or exclude his duty to any visitor or visitors by agreement or otherwise. Premises S1 (3) OLA 1957 – The word “premises” has been given a wide interpretation and would include any fixed or movable structure including any vessel, vehicle or aircraft. London Graving Dock v Horton (1951) - ships in dry dock Haseldine v Daw & Son Ltd (1941) - lifts Wheeler v Copas (1981) - ladder would not fall within the definition of movable structure. Occupier S1 (2) OLA 1957 - stipulates that the rules of the common law shall apply. Wheat v E Lacon & Co Ltd (1966) - the basic test to determine an occupier is one of control over the premises and not exclusive occupation i.e. occupier is any person who has a sufficient degree of control over premises. HELD: Lord Denning stated that the occupier is the person who has the control over the premises. The occupier must have the power of permitting or prohibiting the entry of another person. On the facts of the case, both the Ds and Mr. P had control. There can be more than one occupier at the same time. NOTE: The power of occupier can be delegated too. It is not necessary that the occupier needs to have legal interest or owned the house. As long as he has control over the premises is sufficient. Harris v Birkenhead Corporation (1976) - The local authority had issued a notice of compulsory purchase order and notice of entry but had not taken possession i.e. the local authority had the legal control of the premises. HELD: Local authority was the occupier even though they had not actually taken possession of the premises. OLA 1957

- 18. LAWOF TORT Mrs. Ari Bahmini LLB (Univ of London), CLP (Mal) 46 Visitor OLA 1957 replaces the old common law distinctions between “invitees” and “licensees” and replaces it with a general category of “visitors”. However, the Act is silent on the meaning of “visitor” and the common law applies. Robson v Hallet (1967) - Permission granted can be revoked at anytime. Once permission is terminated, the person must leave the building within reasonable period or otherwise, he will be treated as a trespasser. Lowery v Walker (1911) - HELD: The P was a visitor who had been given implied permission based on the fact that the D had not done anything in 35 years when he took a short cut through D’s farm but was liable when he set a horse loose on his farm that injured the P. Note: The decision in Lowery v Walker has been criticized on the grounds that the judges decided out of sympathy. However, the principle, which emerged, remains good law. Knowledge of presence does not imply permission - Edwards v Railway Executive (1952) - For a number of years, children had been climbing through a fence beside a railway track. The D had repaired the fence whenever they found it broken down. The P was a 9 years old boy who was injured by a train when he entered the premises. HELD: The P was a trespasser and not an implied visitor. This was because the D had taken reasonable steps to prevent the act of trespasser. Entering premises to communicate with occupier does amount to implied licence - A person entering with the purpose of communicating with the occupier will have implied permission, for example, asking directions, the postman etc. Entering premises to exercise a right conferred by law amounts to licence - S2 (6) OLA 1957 - police with search warrants and officials empowered by statute to enter premises. Exercising a public right of way does not constitute a licence - Greenhalgh v British Railway Board (1969) - The P was injured when he stepped into a pothole on a railway bridge. HELD: The P was exercising a right of way and was not a “visitor”. McGeown v Northern Ireland Housing Executive (1995) - An impossible burden would be placed on landowners if they had not only to submit to letting people walk over their land, but also to keep the rights of way in a good condition. Furthermore, a person exercising a right of way does so not by permission. Conditions on a visitor (a) Restriction as to space The Calgrath (1972) - Scrutton LJ, “When you invite a person to use the staircase, you do not invite him to use the banister”. Geary v JD Wetherspoon Plc [2011] EWHC 1506 (QB) - injured whilst sliding down a banister. No liability. Gould v McAuliffe (1941) - P went to the bathroom which was out in the compound and was injured by a dog, which was set loose there. HELD: He was a visitor as there was an implied permission to use the bathroom. (b) Purpose R v Smith & Jones - The D and his friend entered his father’s house with the intention of stealing a TV set. HELD: Although a son will not be a trespasser in his father’s house, but on the facts of this case he became a trespasser as the purpose for which he came into the house was to steal i.e. criminal act. (c) Time Stone v Taffe (1974) - Where the occupier has imposed a limitation of time, the visitor will not become a trespasser immediately after the time period expired. The visitor must be given a reasonable time period to leave the premises. The party was to finish at 11.00 pm. The P was on his way home when he fell down a stairs and died at about 11.15 pm. HELD: The D was liable. OLA 1957

- 19. LAWOF TORT Mrs. Ari Bahmini LLB (Univ of London), CLP (Mal) 47 OLA 1957 What Is “The Common Duty Of Care?” S2 (2) OLA 1957 states that the common duty of care is a duty to take such care as in all the circumstances of the case is reasonable to see that the visitor will be reasonably safe in using the premises for the purposes for which he is invited or permitted to be there. Note: It should be noted that it is the visitor who must be made safe and not necessarily the premises. This could mean the dangerous parts of the premises can be fenced off and need not themselves be repaired so long as the visitors are safeguarded while on the premises. Cunningham v Reading FC (1991) - D permitted the concrete structure of its ground to fall into disrepair so that rioting fans could break lumps off and use them as missiles. P, a police, was injured by the loosened concrete. HELD: D was liable under S2 OLA 1957. Ferguson v Welsh (1987) - The P, who worked for the D, was injured due to the bad work method, which was used by the D. D is liable. Smith v Watermouth Cove (2000) - P climbed over a fence into a wooded area and fell down a 20-metre gully, sustaining serious injuries. HELD: His claim against the park owners failed: there had been no previous accidents of this nature and they had no reason to suspect the fence was inadequate. They had taken sufficient care in all the circumstances to discourage visitors from entering the dangerous area as trespassers. Laverton v Kiapasha [2002] EWCA Civ 1656, CA - A customer P (who had been drinking) slipped on the floor of D's takeaway shop one wet evening. The doormat was not in its proper place at the time, and the floor was wet with water brought in on the clothes and shoes of other customers. HELD: P's claim failed: Hale LJ said that at peak times it would not be reasonable to expect D to ensure the mat was in place and the floor mopped at all times. Mance LJ, dissenting, thought the mat should have been fixed to the floor, though even he would have allowed a 50 per cent deduction for P's contributory negligence. Children S. 2(3)(a) - provides that the occupier must be prepared for children to be less careful than adult. The duty of care owed to children is higher compared to an adult. Thus the duty is a subjective rather than objective, judged from the point of view of the visitor. Moloney v Lambeth LBC (1966) - HELD: The occupier was liable when a four-year-old boy fell through a gap in railings protecting a stairwell, when an adult could not have fallen through the gap. Pearson v Coleman Bros (1948) - P, a 7-year-old girl, left the circus tent to find toilet. She walked past lion cage in separate zoo enclosure and mauled. HELD: D was liable, as the prohibited area had not been adequately marked off. Allurements An occupier must take precautions against children being attracted by allurements. Hamilton LJ in Latham v R Johnson and Nephew Ltd (1913) defined “allurements” as something involving the idea of concealment and surprise, of an appearance of safety under circumstances cloaking a reality of danger. Glasgow Corporation v Taylor (1922) - 7-year-old boy - playing in a public park - attractive poisonous berries - the bush was not fenced off – he ate the berries and died as a result. HELD: The occupiers were liable because the berries constituted a ‘trap’ or ‘allurement’ to the child. Jolley v Sutton LBC (2000) HOL - 14-year-old boy – a boat had been left in an open field near council flat for 2 years - The P and his friends had used a jack to prop up the boat when it fell and injured the boy. HELD: The Ds were liable as it was reasonably foreseeable that a boat will be attractive to children. Ds knew of the boat and that it was a danger but had been negligent in not removing it. The ‘allurement principle’ only applies to children who are lawful visitors. Liddle v Yorkshire (North Riding) County Council (1944) - 7-year-old child – trespassed D’s land with his friends, who had been warned off by the D in previous occasions. There was a heap of sand close to a wall and he was injured trying to show how bees flew. HELD: The D was not liable. Although the heap of sand was an allurement, it could not therefore make him a lawful visitor. Furthermore, a 7-year-old child is capable of knowing that he would be injured.