The political economy of north south trade liberalisation an intra-regional perspective from CEMAC+ and eu

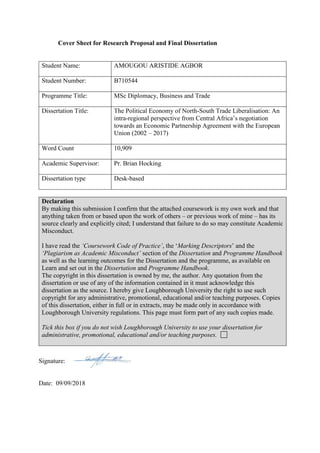

- 1. Cover Sheet for Research Proposal and Final Dissertation Student Name: AMOUGOU ARISTIDE AGBOR Student Number: B710544 Programme Title: MSc Diplomacy, Business and Trade Dissertation Title: The Political Economy of North-South Trade Liberalisation: An intra-regional perspective from Central Africa’s negotiation towards an Economic Partnership Agreement with the European Union (2002 – 2017) Word Count 10,909 Academic Supervisor: Pr. Brian Hocking Dissertation type Desk-based Declaration By making this submission I confirm that the attached coursework is my own work and that anything taken from or based upon the work of others – or previous work of mine – has its source clearly and explicitly cited; I understand that failure to do so may constitute Academic Misconduct. I have read the ‘Coursework Code of Practice’, the ‘Marking Descriptors’ and the ‘Plagiarism as Academic Misconduct’ section of the Dissertation and Programme Handbook as well as the learning outcomes for the Dissertation and the programme, as available on Learn and set out in the Dissertation and Programme Handbook. The copyright in this dissertation is owned by me, the author. Any quotation from the dissertation or use of any of the information contained in it must acknowledge this dissertation as the source. I hereby give Loughborough University the right to use such copyright for any administrative, promotional, educational and/or teaching purposes. Copies of this dissertation, either in full or in extracts, may be made only in accordance with Loughborough University regulations. This page must form part of any such copies made. Tick this box if you do not wish Loughborough University to use your dissertation for administrative, promotional, educational and/or teaching purposes. Signature: Date: 09/09/2018

- 2. The Political Economy of North-South Trade Liberalisation: An intra-regional perspective from Central Africa’s negotiation towards an Economic Partnership Agreement with the European Union (2002 – 2017) By Amougou Aristide Agbor Master Dissertation Submitted in partial fulfilment for the award of Master of Science in Diplomacy, Business and Trade Loughborough University

- 3. 1 Abstract For almost two decades, the Central African negotiating bloc, comprising of eight countries, has been negotiating an Economic Partnership Agreement for the establishment of a Free Trade Area with the European Union. Despite the reiteration of the imperative to arrive at an interregional deal, these Central African states have not been able to adopt a common trade policy in these negotiations as manifested by Cameroon’s unilateral decision to sign an interim agreement with the EU. This dissertation elucidates this deficiency (or absence) of collusion which compromises the uniformity of the region’s trade politics. Following qualitative research, this study confirms that that weak intra-regionalism and the pursuit of national interest within the broader dependency linkages of the region’s countries to the EU and the global economy supersede any political quest for regionalism amongst these countries. Although expressed in political economy agenda as an end, (intra)- regionalism in praxis appears to be more of a means to economic development and one which is superseded by national interest. Key words: Economic partnership Agreement, trade regimes, Central Africa, European Union, trade liberalisation, economic development, Cotonou Agreement, aid, regional integration, intra-regionalism, reciprocity, preferential trade agreements

- 4. 2 Acknowledgements First, I wish to express my gratitude to the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office for granting me the Chevening scholarship. Without their generous financial support, this project might not have seen the day. Most importantly, I wish to profoundly thank my supervisor, Pr. Brian Hocking for accepting to supervise my dissertation and for his invaluable academic and moral support throughout the process. My heartfelt gratitude also goes to the Director of the Institute of Diplomacy and International Governance at Loughborough University London, Pr. Helen Drake, for facilitating the choice of getting Pr. Hocking on board this research. I equally thank my personal tutor, Dr. Nicola Chelotti for vital academic mentorship during my entire studies. This project has been improved conceptually by some insightful recommendations. In that regard, I most especially thank Maryna Shevetsova for the organisation of the summer school on linking theory and empirical research at the Berlin Graduate School of Social Sciences where this research’s framework was presented and critiqued. The consultation with Pr. Felix Berenskoetter (School of Oriental and African Studies, SOAS, University of London) as well as the comments by my discussant, Lucie Lu (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) have been helpful indeed. In addition, I thank my course mates; Emilia Chukwunedum Enwezor and Valdemar Martins-Da-Silva for proofreading this dissertation. Finally, I wish to thank my family for their support. They are the reason why I keep giving my best in each endeavour. In this light, I also thank my team “The Minervans”. The UK has been home for me because they made it enjoyable. This dissertation is dedicated to all diplomats, especially my colleagues at the Ministry of External Relations of Cameroon. It is my hope that our efforts towards building bridges of cooperation will surpass the inclinations to walls of conflict and continue to improve living conditions for all people.

- 5. 3 Contents Chapter 1: Introduction ........................................................................................... 7 Chapter 2: Literature review ................................................................................. 10 Chapter 3: Research Methodology ....................................................................... 14 Chapter 4: Findings ................................................................................................. 16 A. Historical Evolution of EU (North) – Central Africa (South) political Economy of Trade….................................................................................................................. 16 B. Institutions of Regional Integration and the Negotiating Configuration in Central Africa……………………………………………………………………………………..20 C. Central Africa’s institutional framework for negotiating the EPA ....................... 22 D. Contentious issues on the EPA: Opposing perspectives on trade liberalisation.......................................................................................................... 23 E. The EU’s EBA and GSP as Pressure differentiating factors in the Central African negotiating architecture ............................................................................ 25 Chapter 5: Discussion.............................................................................................. 28 A. Why did Cameroon sign the iEPA with the EU?.......................................... 28 National interest.................................................................................................... 28 B. Trade Deflection – Reinforced rules of origin and hardened borders in the CEMAC................................................................................................................. 29 Differentiated trade regimes – divergent interests ................................................ 31 C. Diluting intraregional alliance: From Geography to Status of Development 31 D. External Dependency and Deficiency of Collusion Within Central Africa in its EPA negotiations with the EU.......................................................................................... 32 E. The Challenges of multiple institutional regionalisms and multilateralism on EPA negotiations .................................................................................................. 33 F. The Essence of Timing in Trade Negotiations............................................. 34 Chapter 6: Conclusion and Recommendations .................................................... 35 A. Conclusion .................................................................................................. 35 B. Policy Recommendations............................................................................ 36 C. Limits of the study and avenues for future research.................................... 37 Bibliography ............................................................................................................. 38 Appendices........................................................................................................... 42

- 6. 4 List of Figures and Tables Figures: Figure 1: The Triple Hierarchy of Regional Collusion………………………………………15 Figure 2: REC overlap and the EPA Negotiating Configuration in Central Africa …………21 Figure 3: EPA Negotiating Architecture……………………………………………………..23 Figure 4: Proportion of CEMAC trade within itself, with Africa, and the Rest of the World.33 Tables: Table 1: Alternative EU Trade Regimes available to CEMAC+ countries in the pre- and post-WTO waiver deadline………………………………………………………...27 Table 2: Summary of Cameroon market access schedule……………………………………31 Table 3: Simulations on imports and income variation in the CEMAC resulting from an interregional FTA with the EU…………………………………………………..…32

- 7. 5 List of Terms and Abbreviations ACP: African Caribbean and Pacific States AU: African Union CAP: Common Agricultural Policy CEMAC: Economic and Monetary Community of Central African States COMESA: Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa COMINA: Committee on the Negotiations on the Economic Partnership Agreement CSO: Civil Society Organisation CU: Customs Union DFQF: Duty Free Quota Free EBA: Everything But Arms ECCAS: Economic Community of Central African States ECSC: European Coal and Steel Community EEC: European Economic Community EPA: Economic Partnership Agreement EU: European Union FTA: Free Trade Area iEPA: Interim Economic Partnership Agreement LDCs: Least Developed Countries MFN: Most Favoured Nation clause NSA: Non-State Actors OAU: organisation of African Unity PTA: Preferential Trade Agreement ROO: Rules of Origin ROW: Rest of the World RPTF: Regional Preparatory Task Force STABEX: Stabilisation Fund for Export Income

- 8. 6 SYNDUSTRICAM: Syndicate of Cameroonian Industries SYSMIN: Financing Facility for Mining Products UAM: African and Malagasy Union UEAC: Economic Union of Central Africa USD: United States Dollars WTO: World Trade Organisation

- 9. 7 Chapter 1: Introduction Whether North-South trade liberalisation is an effective development strategy for developing countries is a question which continues to divide political economists as well as developed and developing countries’ governments (Panagariya, 2002, p. 1416). Since 2002, the European Union (EU) and seven different regions of the African Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) group of states have embarked on negotiations for the establishment of Free Trade Areas (FTA) via Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA). These talks which were set to be concluded in 2007, have so far met their objective only in one of the six regions, the Caribbean (European Commission, 2018). In Central Africa, which is the focus of this research, one out of the eight negotiating countries, Cameroon, signed the agreement (European Commission, 2018). The other seven declined it. This dissertation aims to elucidate why within the Central African region, where there exists a customs union to which Cameroon belongs, there have been different outcomes to the EPA negotiations and external trade regimes with the EU. In effect, it should be underlined that one of the main goals of the EPA negotiations is to recalibrate the EU-ACP trade regime to the rules of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in relation to which they have been in non-conformity (Meyn, 2008). Historically, the 1975 Lomé Convention Agreement signed between the European Community and the African Caribbean Pacific Group of countries (ACP) were marked by the principle of non-reciprocity, offering the latter unilateral duty-free quota-free (DFQF) access to the former’s market. The argument was that this arrangement will guarantee improved EU market access to the developing ACP countries and thus contribute to boosting their exports and development. However, this trade regime was discriminatory since it was limited only to ACP countries which were former European colonies and not extended to other developing countries. As depicted with the WTO’s ruling on the Banana III case (Hodu, 2009, p. 236), it was thus deemed contradictory to GATT/WTO principle of non-discrimination (Murray, 1977, p. 9)and requested to be amended. The Central African negotiating bloc comprises of Cameroon, Gabon, Congo, Chad, Central Africa Republic, Equatorial Guinea, Democratic Republic of Congo and Sao Tome and Principe. The first six are all member states of the Economic and Monetary Community of Central African States (CEMAC) customs union. The other two are not part of this customs union. For this reason, the Central Africa negotiation bloc has become commonly known under the appellation CEMAC+ (South Centre, 2007).

- 10. 8 With almost 2 decades of negotiations gone, the states do not seem to agree on a unified position in relation to the EU’s proposed EPA. Cameroon unilaterally signed an interim EPA (iEPA) with the EU in 2007 despite its commitment to a common external tariff (CET) with 3rd parties as ascribed by its CEMAC membership. Such divergences are a manifestation of a deficiency of collusion within the CEMAC+ party which this dissertation aims to analyse. Research Interest and Justification of the study Academic interest Although the question of the role of the policies towards trade in developing countries themselves has been extensively investigated (Page, 1994, p. 1), regionalism is still a very fertile area for research, with new results and interpretations emerging every day that deserve scholarly attention (Schiff & Winters, 2003, p. 11). By focusing on the dynamics of trade political economy among CEMAC+ countries, this study aims to explain how developing countries frame their interests and adopt policies thereof. This study is indeed specific in that it analyses the dynamics of south-south cooperation against a backdrop of north-south political economy of trade. Scholarship on trade and development have focused more on developed countries’ policies and the dynamics of their relations with developing countries without paying as much attention to how these aspects are affected by and affect cooperation among developing countries. Authoritative sources on regionalisms such as (Shaw, et al., 2011) do not pay attention to the central African region which is perhaps the main victim of this academic gap which this research aims to bridge. Policy Implications Considering that the objective of the negotiation is to establish an inter-regional FTA between the EU and the entire Central African negotiating configuration, collusion in the Central African bloc is indispensable. Also, if regional integration, inscribed as a goal in national and regional development policies in the Central African region is to be achieved, an analysis of the diversions that result from trade policy is crucial. To this effect, understanding the dynamics of intra-regional trade cooperation within the framework of EU-CEMAC+ negotiations is essential to adopting the appropriate strategies that ensure that interests are safeguarded, and development policies are better implemented. On this note, the relevance of this study is further stressed by the fact that 40% of CEMAC+ countries’ trade is conducted with their European counterparts. This is therefore an important relationship for them. On the EU side, although this relation amounts to a mere 3%

- 11. 9 of its total trade, the stakes are also important in terms of growth prospects and the rising presence of other major trading nations like China in Africa (Men & Barton, 2011, p. 269). Principal research question: Why has the Central African negotiation bloc been unable to adopt a collusive approach in its negotiations towards an EPA with the EU? A collusive trade policy is understood as one that is “used specifically with a view to promoting regional integration” (Collier & Gunning, 1995, p. 387) Secondary questions: What factors best explain the positions (acceptance or refusal) adopted by the different states in the Central African negotiation bloc in relation to the EPA negotiations with the European Union? Why did Cameroon unilaterally sign and ratify an interim EPA with the EU while other countries in its negotiation bloc declined it and what are the implications for the negotiations and regional integration? Dissertation Structure Following this introduction, Chapter 2 is dedicated to an analysis of the prevalent literature on the questions which this research addresses. In chapter 3, a presentation is made on the methodology by which this study was carried out. Chapter 5 discusses the findings that are laid out in chapter 4. Finally, conclusions and recommendations are made in chapter 6.

- 12. 10 Chapter 2: Literature review While an abundance of literature has been produced on the EPA, more attention has been paid to other blocs such as East Africa, West Africa, Southern Africa, the Caribbean and the Pacific. Enriching analysis on the subject such as (Heron, 2013) have no section dedicated to Central Africa, a gap which this research bridges. Collusion Among African countries in trade negotiation with Europe According to (Collier & Gunning, 1995) developing countries in Africa do not need to collude together in order to negotiate a PTA with Europe. They posit that any inter-regional approach in negotiating FTAs between Africa and Europe is bound to be ineffective if collusion is indispensably pursued among the African countries because this increases coordination and compensation costs. According to them, it is in states’ best interest to keep their decisions on trade policies at the national level, and eventually, by adopting liberalisation at national level, regional integration amongst neighbouring African states will ensue as a by-product. Their argument is closely supported by (Fratzscher, 1996) who asserts that more dissimilar countries have higher potential benefits from integration. However, pragmatically, such an assertion appears limited given that states are already constituted in regional blocs with legal bases for trade policy coordination and therefore cannot act in total inconsideration of this. On collusion and its impact on trade negotiations As stated by (Andriamananjara, 2011, p. 115), if CU members negotiate effectively as a bloc, they can pool their negotiating power and enhance it against the rest of the world, thus affecting the outcome of negotiations. Given the mercantilist nature of trade negotiations, increased negotiating power is likely to lead to a more protectionist outcome (in exchange for better market access). It could also be argued that non-members will act in a more conciliatory way when negotiating with a (single, large) customs union than with separate members, and the result will be smaller requests for concessions. This argument is coherent with that of (Manger & Shadlen, 2015, p. 485) who posit that trade negotiation outcome is affected by political dependency and asymmetry of economic aggregate size of the parties. Plainly, the bigger economic entity has greater leverage in negotiations and can walk out without losing much while the reverse is not true, unless several small economic units collude to amplify their negotiating leverage. Clearly, the question of how many countries are involved and how much power they possess collectively is an important issue in trade negotiations for these reasons (Odell, 2007, p. 18).

- 13. 11 On the Appropriateness of EPAs for African countries (Draper, 2007) argues that the EPAs can only be appropriate for African countries on the condition that supply-side challenges are overcome, and market access constraints are addressed. These, he states, will need substantial “aid for trade” that addresses infrastructural investment and market buttering supportive regulatory framework. (Borrmann & Busse, 2007) emphasize that institutional reform, in terms of eradicating excessive regulation is an indispensable precondition for most ACP countries to benefit from the EPAs and undergo economic development in general. According to the authors, in the CEMAC+, only Gabon passes the institutional test. The other countries have excessive regulation and must reform. Without this, implementing the EPAs would rather be counterproductive for them. According to (Hoekman, 2011), North-South PTAs must shift focus from market access to behind the border regulatory reforms that are supported through development assistance instruments and aimed at boosting the private sector. Given that developing countries still perform poorly in trade exports despite the DFQF access conferred to them via some trade regimes, this is evidence that the real problem is certainly on issues such as bolstering trade capacity, improving the domestic investment climate and maintaining a competitive exchange rate. (Karingi Stephen, 2005) arrives at bleaker conclusions from statistical simulations that demonstrate that EPAs mostly lead to net trade diversion from the rest of the world (ROW) and from other African countries to the EU’s benefit alone. (Perez, 2006) shares this opinion and posits that the Generalised System of Preferences plus regime (GSP+) which offers unilateral DFQF to the EU market is best suited for the development prospects of ACP countries. According to (Storey, 2006), the EPAs are more of a commercial tool than a development instrument as the EU paints it. The move towards FTAs is a means by which the EU intends to ensure that its businesses better access ACP markets. As (Siles-Brügge, 2014) argues, the opposition to the EPA can be explained by the excessive neo-liberal global Europe discourse of the EU Commission which has led to resistances from developing countries and other non-trade actors who advocate regulatory liberalisation. The impact of different trade-development regimes on EPA outcomes According to (Faber & Orbie, 2009), given the internal pressure from states such as the Scandinavians, the EU’s external relations with the developing world has evolved from

- 14. 12 historical articulation advocated by regionalist states such as France to a principles-driven approach advocated by globalists. It is this evolution that led the EU to adopt the Everything But Arms (EBA) initiative which offers DFQF access to all Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and not only ACP countries. This approach has differentiated LDCs from non-LDCs and could weaken intra-ACP alliances. (Hawthorne, 2013) argues that this differentiation of developing countries, which attributes more special treatment for LDCs as compared to the other developing countries, is a salient aspect of global North-South trade politics which relived the LDCs from any pressure to conclude EPA negotiations as opposed to non-LDCs. EPAs and Regional Integration According to (Bartels, 2007), the composition of states within the ACP negotiating configurations could undermine regional integration within the existing RECs because on the one hand, they associate non-members of a given REC to negotiations while on the other hand splitting other RECs. The complexities of conforming to a CET in regional groupings According to (Andriamananjara, 2011) setting and conforming to a CET is a daunting task which requires strong institutions and concessions amongst the different parties to the negotiations. Because of the difficulties in agreeing to CET, trade negotiations within CUs or negotiating configurations can take several years. The author gives scenarios of situations where negotiations on CET took several years. For instance, the EU, arguably the world’s most successful integration project so far took 11 years (1957 to 1968) to completely negotiate its CET. The South American Common Market (Mercosur) took 4 years to negotiate its non-agricultural CET. Also, even when agreements are reached, there are usually exceptions that are designed to accommodate the specific interests of the parties involved. As stated by (Andriamananjara, 2011) “in the current wave of regionalism, in which flexibility and speed are valued, membership in a CU, if played by the rules, could constitute a straitjacket for some countries.” Such flexibilities usually concern tariff schedules and sector specific considerations. Examples include Mercosur wherein not all sectors are covered by the CET and includes special regimes for sensitive sectors such as automobiles and sugar. Another example provided by the author is the EAC CU wherein countries like Kenya and Tanzania can unilaterally reduce tariffs on imports of grains for reasons linked to food security. It therefore appears from the literature that fully functional CUs are a rare phenomenon in the global trading regime. (Baldwin & Freund, 2011) agree with

- 15. 13 (Andriamananjara, 2011, p. 129) on the crucial responsibility of supranational decision- making institutions to “keep all external tariff in line in the face of changed in antidumping duties; special unilateral preferences to third nations such as the Generalised System of Preferences,; and tariff changes in multilateral trade talks.” According to these authors, only two types of such institutions exist in the world today, the EU, and nations involved in superhegemon relations i.e., France and Monaco; Switzerland and Liechtenstein; and the South African Customs Union). In a nutshell, although the flexibilities accommodated in trade negotiation blocs facilitate a compromise for the conclusion of a deal, they not only “reduce the transparency and effectiveness of the CU, but they also can complicate trade negotiations and increase transaction costs. Furthermore, they reintroduce the potential for trade deflection—the very phenomenon that the CU is designed to prevent” (Andriamananjara, 2011, p. 115). (Cf. p 29 of this dissertation for a definition of trade deflection) The challenges of multiple overlapping membership in RECs on Trade Collusion (Andriamananjara, 2011) highlights that when states belong to several RECs, difficulties may arise because the different groups to which they belong might have dissimilar or even conflicting operational or liberalization modalities, which could render member countries’ commitments incompatible. As a result, CUs could be less effective as they confuse traders (and even customs officers) as to which commitments or tariff schedules apply to a particular shipment. Transaction costs could be heightened as traders seek to find their way around a number of trade regimes with different tariff schedules, Rules of Origin (ROO), and procedures. Nevertheless, the author notes that despite these counterproductive consequences, states have not been dissuaded from a predilection to multiple REC membership. Indeed, he provides examples of cases in which a CU member alone negotiates an FTA with a third party such as the FTAs between the EU and South Africa (a member of Southern Africa Customs Union) and between the United States and Bahrain (a member of the Gulf Commission Council); Lesotho, Namibia, and Swaziland belong to COMESA while also belonging to SACU, and Tanzania is a member of both the SADC and the EAC etc. What this situation proves is that the deficiency of collusion is not unique to Central Africa. However, on its part, this dissertation aims to offer less breadth and more depth by delivering a complementary micro analysis of the dynamics of North-South political economy via the EU-CEMAC+ case.

- 16. 14 Chapter 3: Research Methodology According to (Klotz & Prakash, 2008, p. 12), the method a study uses cannot be dissociated from its research questions. Based on this consideration, this research shall be conducted primarily by qualitative methods. More precisely, the content analysis methodology shall be employed (Pashakhanlou, 2017). The choice of this methodological approach is justified on the basis that it gives room to constructive interpretation of discourse in the conduct of trade negotiations and practices between the EU and CEMAC+ countries. Indeed, trade relations are not just about monetary values which could warrant quantitative approach. Trade carries with it distribution of resources, linkages and dependencies with power implications which can be well understood qualitatively. Data collection This dissertation relies principally on secondary data which is made public by the EU Commission and the respective Central African Governments involved in these negotiations via the CEMAC Secretariat. The final communiques of the negotiation meetings are generally available on the websites of these entities and on those of some of the ministries of foreign affairs, economy and trade and the Permanent representations of the said countries to the EU. On this note, another vital source of data is the Ministerial Committee on the negotiations of the EPA, known by its French acronym, COMINA, which is the ad-hoc grouping of the Ministers of Trade and Economy of the CEMAC+ negotiation countries that gather at least twice a year to review the progress made on these negotiations. Important data is also gotten from official documents of specialised organisations such as the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), the International Trade Centre (ITC), the WTO, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Although interviews were not conducted by the researcher, some very important interviews granted by key actors of the negotiations and made public in magazines and gazettes have been explored. All these data supplement the main scientific literature; books and articles, employed in this research. Theoretical Framework This study adopts the framework of (Collier & Gunning, 1995, p. 388) in assessing the effectiveness of collusion and regional integration in trade policy formulation in the Central Africa negotiating configuration. The authors state that for regional integration to be the appropriate objective for trade policy, the following conditions must all be met: • Collusive trade policy must be superior to unilateral trade policy • Reciprocal discrimination must be superior to reciprocal non-discrimination

- 17. 15 • Regional reciprocal discrimination must be superior to south-north reciprocal discrimination The data collected for this research is analysed along the lines of this framework by seeking discourses that are more aligned to any of the six trends identified in these three conditions. For instance, emphasis is laid on arguments given by a high-level negotiator in an interview granted (from a secondary source) to explain why his country solely adopted a unique policy while the rest of the negotiating configuration chose an alternative path. In such a situation, the dynamics of unilateral trade policy as against collusive trade policy is investigated discursively and via a process tracing approach. Figure 1: The Triple Hierarchy of Regional Collusion Source: Designed by researcher from the framework of (Collier & Gunning, 1995). Collusive trade policy Unilateral trade policy Reciprocal discrimination reciprocal non- discrimination Regional reciprocal discrimination south-north reciprocal discrimination

- 18. 16 Chapter 4: Findings A. Historical Evolution of EU (North) – Central Africa (South) political Economy of Trade EU-CEMAC+ negotiations are grounded in colonial policies and post-colonial regimes which evolved along the lines of structural relations in the international system. (Brown, 2002, p. 19) in his reading of (Barraclough, 1967) coins: “The political economy of North-South relations, as an inter-state phenomenon, are a creation of the post-war era, the roots of which lie in the process of decolonization. This was an historic process for the modern international system. At no other time has so great a number of sovereign states been created in so short a space of time: between 1945 and 1960 more than 40 new states came into being, representing a geographical spread of the state system of enormous importance (Barraclough 1967)” The colonial trade regime: Exogeneous control of the territories This colonial trade regime was essentially extractive and the French and British shaped the economies of the colonies to their respective needs (Jones, 2013, p. 60). Colonial trade as Adam Smith had contended was always detrimental to the colonies, all other nations and even to the “mother nation” in the end, like all other mean and malignant expedients of the mercantile system (Raffer, 1987, p. 13) (Smith, 1976, pp. 610-). After two devastating wars, France, via the Schumann declaration, took the initiative to establish strong European institutions aimed at sustaining peace among European countries and Africa was an essential aspect of it as revealed by this extract (Schuman, 1950): “With increased resources Europe will be able to pursue the achievement of one of its essential tasks, namely, the development of the African continent. In this way, there will be realised simply and speedily that fusion of interest which is indispensable to the establishment of a common economic system; it may be the leaven from which may grow a wider and deeper community between countries long opposed to one another by sanguinary divisions.” With this goal in mind, the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) was instituted and seven years after Schuman’s declaration, the European Economic Community (EEC) was born via the Treaty of Rome of March 1957. At this point, decolonisation was not envisaged, and member states of the EEC clearly intended to treat their colonies as if they were participants in the evolving Customs Union. As stated in Article 133.1 of (The Treaty of Rome, 1957): “Customs duties on imports into the Member States of goods originating in the countries and territories shall be completely abolished in conformity with the progressive abolition of customs duties between Member States in accordance with the provisions of this Treaty.”

- 19. 17 The colonies were a key part of Europe’s international economic policy because they provided some of the raw materials which Europe needed for its industries. From the colonies’ perspective, being under the control of foreign administration meant that they did not have institutional autonomy and the bureaucratic architecture to develop and implement trade policies with Europe and the rest of the world. Independence of the colonies and the perpetuation of dependency reflected in the Yaoundé I and Yaoundé II Conventions Following the accession to independence of several African states in the early 1960s as well as the expiry of the Trade provisions in Part IV of the Rome Treaty, 18 African Francophone countries1 embarked on negotiations with the EEC for a new trade regime. Contrarily to the UK which accorded unilateral trade preferences to its colonies, France successfully advocated for EEC member states to adopt reciprocity in trade liberalisation with the territories. Indeed, the trade system after the First World War was based on the principle of reciprocity (Mennes & Kol, 2005, p. 11). This EU policy towards Africa was highly criticised by leaders of African independent movements at the time such as Ghana’s President, Kwame Nkrumah, who considered the EEC as a system of collective colonisation (Jones, 2013, p. 62). There was some perception of this regime being divisive, neo-liberal and exploitative of Africa (Campling, 2015, p. 63). Under France’s influence, the EEC agreed to the establishment of a European Development Fund (EDF) whose goal was to fund development projects in the colonies. These francophone African states in these negotiations had little room for manoeuvre as most of their trade was done with Europe (France) and they depended significantly on European firms for the production of their main export products. For them, the cost of giving up preferential access into the European market and losing aid and other forms of assistance was too high. At the time of negotiating the Yaoundé II convention with the EEC, these newly independent African states still lacked the institutional capacity to secure more concessions from the EEC. An effective strategy which they undertook was to form a united front via the creation of the Union Africaine et Malgache (UAM)2 . Despite the heterogeneity of its members, they were able to maintain a common position in the negotiations articulated 1 These included all the countries of the Central African negotiating configuration except for Equatorial Guinea and Sao Tome and Principe which are of course not Francophone but rather Hispanophone and Lusophone respectively. 2 This could be translated in English as the African and Malagasy Union

- 20. 18 around 3 main demands: negotiating on a basis of parity and equality of representation, maintaining advantages equivalent at least to the Rome Treaty and extracting an EEC- financed commodity price stabilisation scheme (Jones, 2013). Since these countries had weak bargaining power, they appealed to the honour and integrity of the EEC to see through their development needs. Contrary to their requests, aid allocations that were agreed upon were significantly lower, the EEC rejected their request for the joint management of aid and the creation of the commodity price stabilisation fund. As power asymmetries weighed against them, these francophone African states agreed to this deal. The immediate trade environment in the former British colonies It is important to understand how the trade regimes linking Britain’s former colonies and the EEC were structured as this had an impact on the wider ACP group later. Indeed, former British colonies were seeking a new form of trade relations with the EEC. Most notable of these was Nigeria, Africa’s second largest economy. Nigeria’s negotiations with the EEC started in 1963 and culminated in the Lagos Treaty in 1966. The Nigerian government was strongly opposed to any idea of reciprocity in trade regimes with developed EEC countries. Also, as a matter of pragmatism, Nigeria was also strongly opposed to any form of preference that could be granted to francophone African countries which as it perceived, made its own productions uncompetitive on the EEC market (Jones, 2013, p. 67). In its negotiations, Nigeria rejected every aspect of aid in the deal and focused on market access to the EEC on the same terms as the Yaoundé Agreement, while offering a margin of 2-5% to the EEC on some product lines that were carefully chosen in such a manner that they were not of interest to its other major partners: the UK and the USA. Despite long protests by the French Government, the deal was signed (Jones, 2013, p. 68). In comparison to the francophone countries, Nigeria had a significant leverage in these negotiations and was able to negotiate for reciprocity because it did not depend as much on trade with the EEC (its main trading partners were the US and the UK), did not associate any form of aid with trade and so could easily walk away from the negotiations without losing out too much. Beyond this however was also the skill and awareness of Nigeria’s negotiators in building on these structural factors in securing themselves a better deal. Moreover, most EEC member states (Germany, The Netherlands etc.) were interested in finding a trade agreement with former British colonies in order to dampen their criticism of trade arrangements with francophone Africa.

- 21. 19 In a similar fashion, the East African nations led by Tanganyika, i.e. Tanzania, embarked on trade talks with the EEC by emphasizing the principle of non-reciprocity which was gaining significant traction in international arena such as GATT and UNCTAD. In the end there was some form of symbolic reciprocity but not as profound as in the Yaoundé Agreement. The Lomé Agreement and non-reciprocity in favour of ACP Countries Broader trade negotiations took place between the EEC and the 46 countries of the ACP which comprised of signatories to the Yaoundé II Agreement, Commonwealth States in Africa and the Pacific and some other countries that had not been in any previous trade agreement with the EEC. These negotiations were prompted by Britain’s accession to the EEC in 01st January 1973 (CVCE, 2015). As the important question at that time was articulated on what will become of the Britain’s preferences to its former colonies, the EEC invited them for talks on grounds that they would adhere to the Yaoundé convention terms. This was not the case as these anglophone countries firmly rejected any form of reciprocity (Jones, 2013). Nigeria’s proactive diplomacy bolstered ACP countries to speak with one voice and gain substantially in the new trade regime that was agreed upon. Indeed, the Lomé Agreement guaranteed unilateral DFQF access for ACP countries into the EEC’s market with no obligation on their part to reciprocate. The agreement also created an operational compensation scheme (STABEX) for agricultural products. When world prices fell, the ACP states received interest-free repayable compensation from the EEC. Also, unlike in the previous agreements, ACP countries were not obliged to provide preferences to European companies or guarantee the free flow of capital. The second Lomé Agreement which was signed on 31 October 1979 instituted the system of stabilisation of earnings from mining products, SYSMIN, which allowed the EEC to provide urgent financial assistance to ACP states experiencing serious upheaval in the mining industry if it represented a major proportion of their total export volume, and the EDF was doubled (CVCE, 2015). These characteristics of the Lomé framework based on partnership, dialogue, contractuality and predictability –gained EU–ACP relations the label of a ‘unique model of North–South cooperation (Scappucci, 1998, p. 109). They were crucial to developing countries considering that the volatility of most commodity prices on world markets, as well as deteriorating terms of trade relative to manufactures, had been a major problem for development planning and finance (Yeats, 1979, p. 5).

- 22. 20 The Cotonou Agreement: Agenda setting for WTO conformity in EU-ACP trade regime By the mid-1990s it became obvious that the EU wanted to put an end to the unilateral preferences offered to ACP countries. Indeed, this trade regime had been contested severally by GATT/WTO members for its non-conformity with the organisation’s principle of non- discrimination. The EU advocated for the establishment of FTAs with ACP countries. In its approach to the negotiations, the EU put an end to 2 fundamental aspects by splitting off the ACP Group: non-reciprocity and non-differentiation. The former had been a critical element of the ethical discourse of the development advocacy of developing countries in global trade governance while the latter had been a key factor in conferring negotiation advantage to the ACP countries. The Cotonou Agreement which was finally signed in 2000 provided for a maximum of 8 years for the negotiation of regional EPAs with ACP countries that were now divided into 7 groups (European Commission, 2018): ➢ Central Africa ➢ Eastern and Southern Africa ➢ East African Community ➢ Southern African Development Community ➢ West Africa ➢ Caribbean ➢ Pacific B. Institutions of Regional Integration and the Negotiating Configuration in Central Africa Regional integration in Central Africa has been structured around two main institutions. The first major one is the CEMAC while the second, which has been relatively less active on the integrationist agenda is the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS). In addition to the 6 CEMAC states, ECCAS is composed of the other 2 CEMAC+ states; DRC and Sao Tome and Principe as well as Angola and Burundi. CEMAC An understanding of regional integration in Central Africa warrants a broader perspective from the entire continent. Indeed, as African states began to gain independence in the 1960s, they met in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and founded the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) on 25 May 1963 where the Heads of state decided to implement regional integration via political, judicial and economic cooperation as a means to achieve collective

- 23. 21 development. (Sommo Pende, 2010). To achieve this goal, these leaders divided the continent into 5 regional economic units (Northern, Southern, Eastern, Western and Central Africa) within which institutional mechanisms had to be developed to this effect. In this regard, Cameroon, CAR, Chad, Gabon and Congo signed the treaty creating the Customs Union of Central African States (UDEAC) on 08 December 1964. Equatorial Guinea was the 6th member to join on 01January 1985. However, after 30 years of cooperation within the UDEAC, intra-regional trade and movement of people was not effective, and it was obvious that there was a need for a new boost in regionalism within central Africa (Sommo Pende, 2010). The governments of UDEAC decided to revamp the institution by creating the CEMAC which was born out of the treaty of Ndjamena on 16 March 1994. This goal within the framework of this sub-regional institution was to harmonise regional policies and institute a judicial and economic environment that would boost investment and establish a common market in Central Africa. ECCAS On its part, the ECCAS was born out of the initiative of then Gabonese President, Omar Bongo. The declared objective of the organisation at its creation in 1983 was to consolidate regional integration in central Africa and ultimately ease the creation of the African common market and the African Economic Community. In terms of trade, the following targets were set in the founding texts of the organisation: free movement of people, easing customs procedures, instituting compensatory mechanisms, adopting a CET with CEMAC, eliminating tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade and adopting agricultural and industrial policies (ECCAS, 2014). Figure 2: REC overlap and the EPA Negotiating Configuration in Central Africa Source: Translated by researcher based on map from (South Center, 2007, p. 2)

- 24. 22 C. Central Africa’s institutional framework for negotiating the EPA The Central African negotiating configuration carries out joint negotiations on its position within the framework of the Committee for the Negotiation on the EPA, which is composed of member states’ ministers of Trade and Experts. The Council of Ministers of the CEMAC mandated the Executive Secretariat of the CEMAC to take joint efforts with the General Secretariat of the ECCAS in view of negotiating and concluding EPAs with the EU. In this regard, the Council created a Regional Committee for Negotiations with the goal of meeting the following 5 objectives: • Create a FTA between the EU and CEMAC countries + Sao Tome and Principe3 which conforms to the rules of the WTO • Prioritise development (in Central Africa) • Deeping regional integration in Central Africa • Boost trade cooperation • Improve competitivity (building capacity) According to the road map of the negotiations, the organigram is structured thus (Biyoghe Mba & Hubner, 2004): The Council of the Ministers of the (Economic Union of Central Africa) UEAC4, composed of three ministers from each member state. It issues the directives by which the negotiations shall be undertaken. The Trade Ministerial Committee, composed of the trade ministers of the central African countries. Its role is to supervise the ACP negotiations at a political level. It controls the work of the negotiating structures and particularly approves the conclusions of the Regional Negotiating Committee. It is presided by the minister of trade of the country occupying the presidency of the negotiations and meets before and after each negotiation round. Its decisions ae validated by the Council of Ministers of the UEAC for CEMAC and the Council of Ministers for the ECCAS. The Regional Committee for Negotiations which oversees the negotiations at a technical level is presided by the Executive Secretary of the CEMAC, assisted by the Deputy Secretary General of the ECCAS. Its competence is codified in the regulations of CEMAC n°02/02/UEAC-085-CM-08 of 03 August 2002. 3 DRC joined the negotiations later, so was not part of the initial bloc) 4 UEAC is an organ of the CEMAC in charge of economic cooperation

- 25. 23 The Technical Working Groups prepare the works of the RCN and are presided by the Director of Trade of the CEMAC, assisted by the Director for Trade of the ECCAS. In addition, the joint Regional Preparatory Task Force (RPTF) was created to facilitate links and coherence between the trade negotiations and related financial assistance (ECDPM, 2006, p. 3) Figure 3: EPA Negotiating Architecture (South Centre, 2007, p. 4) D. Contentious issues on the EPA: Opposing perspectives on trade liberalisation Loss of tariff revenue From the point of view of the African states, the major challenge with the EPA is the decrease of government revenue resulting from the elimination of tariffs on EU products (South Centre, 2007, p. 11). On the flip side, the EU believes that states’ dependence on tariffs as a major source of revenue is not sustainable and has agreed ‘in principle’ to support programmes that enhance the competitiveness of the business sector, help governments transition out of dependence of tariffs revenue, and implement fiscal reforms (South Centre, 2007, p. 10). The Infant Industry Argument Developing countries’ governments contend that liberalisation of their economic environments to European products will expose their industries to unrivalled competition from more efficient European manufacturers and certainly lead to their demise given their relative less capacity. EU Common Agricultural Policy CAP (non-) Reform The scepticism towards the EPA is heightened by resistances within the EU to put an end to its agricultural subsidies as requested by most developing states within the framework of the Doha negotiations for a reform of the multilateral trading system (Conceição-Heldt, 2011, p. 162). Indeed, these subsidies have been condemned for causing unfair competition,

- 26. 24 encouraging dumping and outcompeting local producers with cheap imports (South Centre, 2007, p. 16). Farmers in developing countries who sign the EPA and whose governments do not provide them with similar means, will face direct disloyal competition against EU farmers who are subsidised. In these countries, agriculture is an important sector and a major employer. Chad, one of the CEMAC+ states, has been the most vocal in calling for an end to EU subsidies which, as it argues, negatively affects its own domestic cotton sector and amplifies poverty rates within its population (South Centre, 2007, pp. 16-17). For 2001-2002 alone, the EU granted 1 billion USD worth of subsidies to cotton producers alone (Baffes, 2005, p. 264). This issue is a very sensitive one which causes friction between developed and developing economies (Das, 1990, p. 125). Mercantilism reflected in Aid for Development Commitments requested from the EU The issue of aid for development support appears to have been the most contentious issue throughout the negotiations. Writing in 2007, the South Centre noted that “negotiations of phase 2 had, in fact, been blocked since July 2006, owing to strong divergences among African and European negotiators concerning the format, definition and contents of the EPA accompanying measures aimed at levelling up the productive capacity of Central Africa” (South Centre, 2007). Central Africa asked for the inclusion of the matter in the formal EPA negotiating process. While the EU recognised their importance, it maintained that the negotiations should focus on trade aspects only and insisted that the developmental dimension should be covered by external instruments such as the WTO Aid for trade and the programming of the European Development Fund (EDF). Indeed, the establishment of the RPTF along the lines of the EPA negotiations were meant to facilitate dialogue on these questions on capacity building (Cf. p 23 above). The EU decided to push the agenda process into the final stage of negotiation while promising to address this conflicting issue at a later stage. 5 This approach was inefficient as portrayed by its rejection by the majority of the CEMAC+ countries. In the EU-Cameroon iEPA, no concrete engagement on this matter was taken. Rather, just a document recognising the needs of the region in terms of overcoming supply side constraints via capacity building was annexed to the main agreement (EU - Cameroon, 2009, pp. 39-44). 5 « Communiqué Final du Comité Ministériel Commercial Conjoint élargi » (6 February 2007). Available at http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2007/february/tradoc_133268.pdf.

- 27. 25 This has continued to be contentious issue in these negotiations as they protract 18 years after their commencement. In their most recent extraordinary summit, the Heads of state of the CEMAC, in their final declaration stressed that the “adoption of a compensatory mechanism which allocates for fiscal loss resulting from the liberalisation of Central African markets must be considered a priority in these negotiations (…) These negotiations must deliver a regional Agreement which is complete, just and equitable on a commercial and financial basis and capable of guaranteeing the development of the region. (CEMAC, 2016)” E. The EU’s EBA and GSP as Pressure differentiating factors in the Central African negotiating architecture A crucial question is “in a case of a “no deal” on the EPA negotiations, were these countries all under the same threat of trading with the EU under the Most Favoured Nation clause (MFN) which would have stripped them of SDT and DFQF access on the EU market? It appears that the EU’s multiple development-trade regimes articulated on the EBA and GSP had a differentiating effect on these states choices. The EU’s existing EBA regime provided the opportunity for five of the eight negotiating CEMAC+ countries to maintain DFQF access on the EU market without any obligation to reciprocate. Indeed, this regime which was coined under the premise of the WTO’s enabling clause, offered all LDCs (not only those from the ACP as with the contested Lomé agreement) the possibility to be exempted from the MFN clause and receive SDT which other developing countries are not eligible to. These LDCs include Chad, CAR, Equatorial Guinea, DRC and Sao Tome and Principe. In plain terms, European external trade policy bifurcated the states of the Central African negotiating configuration into 5 LDCs which could continue to benefit from Lomé equivalent market access provisions under the EBA and 3 non-LDCs without these privileges (Cf. table 1, p.27 below). However, the history of the EBA precedes the EPA negotiations and was established out of a global pressure in the WTO for extension of SDT to all LDCs and not only former colonies of European countries. The EU was obliged to grant Lomé style preferences to non- ACP LDCs and this was an unprecedented move in its relations with the developing South (Faber & Orbie, 2009, pp. 778-779). This was manifested by the adoption in 1997 of the EBA initiative which allowed all goods from LDCs except arms to access the EU market DFQF with no obligation to reciprocate. This move drew a clearer line between LDCs and non- LDCs and blurred the position of the ACP, and its negotiating configurations, as a distinct ‘holistic’ category in Europe’s trade ambit (Faber & Orbie, 2009, p. 778).

- 28. 26 At the time, this seemed inconsequential. But even without directly addressing the status of the ACP group, it set a precedent for the differentiation between ACP LDCs and ACP non-LDCs (Faber & Orbie, 2009, p. 779). It was clear at this stage that reciprocal trade relations would be pursued. But what appeared problematic was the difficulties that arise when non-reciprocal treatment is given to LDCs participating a FTA, a difficulty which the Commission had foreseen. If ACP LDCs agreed to EPA, they will face less favourable treatment than their LDC counterparts outside of the ACP. In this light the Cotonou agreement was coined with some conditionality of interest stating that only countries that found themselves as being in a position to do so could negotiate the EPAs. The ACP LDCs had a very strong incentive to side with non-ACP LDCs and discard the EU-ACP trade framework, a move which non-LDC ACP countries could not afford (Faber & Orbie, 2009). Writing in 2002 as regional EPAs started to be negotiated (McQueen, 2002, p. 109) noted that: “The EU special preferences for the LDCs create a potential obstacle for the negotiation of EPAs since practically all of the ACP sub-groups which could negotiate EPAs include LDCs. The LDCs have now been given the same duty and quota free access to the EU market as they could obtain under an EPA, while if they participate in an EPA they will have to offer the EU free access to their domestic markets.” Of the three countries in the negotiating configuration that were not eligible for the EBA, the Republic of Congo was eligible to the GSP which although not as generous as the EBA scheme equally offers DFQF on most products exported from beneficiary countries into the EU (Cernat, et al., 2004, p. 220) (Liapis, 2007). There was therefore little incentive for Congo to sacrifice its customs revenue within the framework of the EPA whereas it could continue to benefit from substantial access on the EU market via the GSP scheme. In a nutshell it can be argued that the 5 countries that were eligible for the EBA scheme as well as the sole country, Congo that was eligible for the GSP scheme had not and currently still do not face the same pressure that the other two countries; Cameroon and Gabon faced in the advent of a “no deal”.

- 29. 27 Country Cameroon Gabon Congo Chad C.A.R Eq. Guinea DR Congo Sao Tome &Principe Status Developing Middle income developing Developing LDC LDC LDC LDC LDC Alternative Regime to maintaining DFQF access in EU market post waiver on Lomé provisions None None GSP EBA EBA EBA EBA EBA Trading Regime post- WTO waiver EPA MFN GSP EBA EBA EBA EBA EBA Table 1: Alternative EU Trade Regimes available to CEMAC+ countries in the pre- and post-WTO waiver deadline

- 30. 28 Chapter 5: Discussion A. Why did Cameroon sign the iEPA with the EU? National interest According to Cameroon’s minister of economy, the main motivation for signing the EPA was the country’s quest to avoid any distortions on its exports as of the 31st of December 2007 [expiry date of the WTO waiver in Lomé discriminatory preferences] (Motaze, 2016). He further adds that by signing the agreement Cameroon “benefited as of the 01st of January 2008, from DFQF access on the EU market for its exports such as banana, aluminium, cocoa products, wood as well as other fresh and processed agricultural products” (Motaze, 2016). Cameroon’s decision to sign this agreement as well as the other countries’ refusal to do so is therefore an expression of primacy of national interest over regional solidarity considerations in the conduct of trade diplomacy. (Pigman, 2016, p. 15) contends that trade diplomacy frames trade negotiations as the essential and original form of human negotiation, in that it resolves political disputes over who-gets what questions. For as the Cameroonian government perceived it, at least six of the other seven negotiating countries of the configuration had alternative legal and WTO recognised regimes through which their products could continue to benefit from DFQF access on the EU market. Had Cameroon not signed the agreement, its exports would have been outclassed competitively by other DFQF access countries including the very ones with whom it was a member within the Central African negotiating configuration. As coined by the Cameroonian minister of economy, “by concluding this bilateral agreement with the EU, Cameroon sought to preserve its trade interests” (Motaze, 2016). However, the Cameroonian government adopted a liberalisation schedule which pushes the burden of fiscal impact to a later date (2023) and made liberalisation exemptions amounting to about 20% of trade in sensitive sectors such as agriculture. Nevertheless, the argument of ‘national interest’ is one that must be approached with caution in political economy analysis because as (Hocking & McGuire, 1999, p. 3) contend: “the very nature of trade policy, with its focus on balancing the economic interests of a range of domestic constituencies, undermines the notion of the state as a unitary actor, pursuing a clear and identifiable ‘national interest’. Indeed, in many senses, trade politics, concerned as it is with the distribution of resources within and between political communities, is amongst the clearest manifestations of the processes determining who gets what, why and how. And as the trade agenda becomes more complex, explaining how trade policy is formulated and articulated

- 31. 29 demands that the role and interactions of a range of governmental and non- governmental actors be taken into account.” Based on this, and following profound research conducted by (Jones, 2013, pp. 272- 273), it was found that the lobbying action from non-state actors (NSA) such as the Group of Businessmen in Cameroon (GICAM), the Syndicate of Cameroonian Industries (SYNDUSTRICAM) and other civil society organisations (CSO) that opposed the iEPA, was not sufficient to stop the Cameroonian government from signing the agreement. This is symptomatic of the high degree of governmental centralisation in this region where non-state actors are not as influential as in other regions (Jones, 2013, p. 273). However, the other countries of the CEMAC+ whose interest laid in refuting the EPA incorporated some of the arguments of these NSAs (Jones, 2013, p. 273). Consequently, national interest as alluded to in this research refers to the official government position and in no case assumes uniformity of preferences within the different CEMAC+ states. B. Trade Deflection – Reinforced rules of origin and hardened borders in the CEMAC Article 4 of the CEMAC treaty established a common external tariff (CET) applied to all third country imports and the gradual removal of tariffs on intra-regional trade. Furthermore, there are efforts to harmonize the common external tariffs between CEMAC and the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) and introduce the free circulation of goods (South Centre, 2013, p. 12). Also, according to Article 21 of the EU-Cameroon EPA, new tariffs cannot be introduced by both Parties and the current level of tariffs must be maintained and cannot be increased. Therefore, Cameroon cannot impose higher tariffs on goods from the EU market again, and even if were decided through renegotiations for the CET among CEMAC and/or ECCAS Member States. The policy space currently available for Central African States to (re-)agree on the Common External Tariff is limited by this consideration (South Centre, 2013). Cameroon’s sole implementation of the EPA implies that the CET of the CEMAC vis-à-vis the EU is compromised and the issue with this situation is that it could lead to trade diflection - a situation in which goods from outside the FTA are shipped to a low-tariff country and then transhipped tariff-free to the high-tariff country (Andriamananjara, 2011, p. 113). Such roundabout shipping patterns, which have the sole purpose of exploiting the existing tariff differential, are inherently inefficient and can create friction among members.

- 32. 30 To counter trade deflection in FTAs or ineffective CUs, states resort to a ROO system which can take various forms, but generally requires that goods (or value added) qualifying for tariff-free trade be produced within the PTA and that imports from outside pay the tariff of the destination country, even if they pass through another member country (Andriamananjara, 2011, p. 113). The ineffectiveness of the CET in the CEMAC could lead to hardened borders between the Central African countries as the non-EPA countries reinforce their assessment of the origin of goods crossing intraregional borders. Also, ROO in EPA negotiating countries such as those of the CEMAC impose costs greater than 3% of the value of export because of information constraints and institutional difficulties (Francois, 2006, p. 61). Theoretically, had a CET been fully in force, such internal controls would not be necessary. (Andriamananjara, 2011, p. 113) states that “In practice, rules of origin are particularly complex, and their implementation costs can be high. They necessitate significant internal border controls to ensure compliance and to collect the relevant customs duties.” Therefore, the EU’s special provisions for LCDs increases ROO tendencies and decrease possibility for regional integration within African regional blocs, including the CEMAC+ (McQueen, 2002). While the COMINA has taken decisions recently to increase surveillance and capacity building for ROO (COMINA, 2017, p. 4), this measure could be a bottleneck for free trade if CEMAC states (and CEMAC+) adopt conflicting trade policies. However, it must be noted that the possibility of trade deflection [and jumping investment] may incite non-signatories of the CEMAC to lower their tariffs to prevent imports from going through Cameroon. Eventually, this may lead to a converge of interests on an inter-regional EPA with the EU and thus a collusion of trade policy. For this to be achieved, more policy coordination and flexibility towards the specific interests of CEMAC+ countries are required.

- 33. 31 Table 2: Summary of Cameroon market access schedule Source: (Bilal & Stevens, 2009, p. 115) Differentiated trade regimes – divergent interests C. Diluting intraregional alliance: From Geography to Status of Development The most important allies in the norm entrepreneurship endeavour to maintain unilateral SDT for the ACP LDC countries in the Central African negotiating bloc is the group comprising of the other non-ACP LDCs. This weakens group cohesion within the Central Africa negotiating bloc, coupled with Cameroon’s decision to sign the EPA. This weakens cooperation despite declarations made by the governments of CEMAC that measures will be taken to prevent Cameroon from paying a penalty for violation of the community’s regulation and signing this deal all alone. As explained by (Andriamananjara, 2011), trade deals are not simply all about trade. Indeed, “there are many possible rationales for choosing a CU over an FTA, including political and economic ones. Some regional groupings consider the establishment of a CU a prerequisite for the future establishment of a political union, or at least some deeper form of economic integration, such as a common market. The Abuja Treaty of 1991 envisaged gradual implementation in the following stages: creation of regional blocs, by 1999; strengthening of intrabloc integration and interbloc harmonization, by 2007; establishment of an FTA and then a CU in each regional bloc, by 2017; establishment of a continentwide customs union, by 2019; realization of a continentwide African Common Market (ACM), by 2023; and (f) creation of a continentwide economic and monetary union (and thus also a currency union) and a parliament, by 2028.

- 34. 32 Therefore, the current divisions amongst Central African countries along the different trade-development regimes of the EU and the distortions to the CET thereof, goes beyond the sole issue of trade to question the region’s wider economic and political objectives. D. External Dependency and Deficiency of Collusion Within Central Africa in its EPA negotiations with the EU Trade diversion among Central African countries The primary effect of PTA is that they discriminate against non-members. In the case of the EU-Cameroon EPA which establishes a FTA between both entities, trade could be diverted from other African countries in favour of the EU (Karingi, et al., 2004) . Also, even in the eventuality of an intra-regional trade between the Central African negotiating bloc and the EU, considerable trade will be diverted from some of those countries in favour of the EU. Simulations conducted by UNECA using partial and general equilibrium forecast substantial revenue loss among CEMAC countries in the eventuality of an interregional EPA (Cf. Table below). Country Imports variation from the EU Income deficit in billions of US dollars Variation of lost income Cameroon 28.58% -149,256,117 -69.60 Congo 29.11% -75,104,052 -55.20 Gabon 29.96% -74,302,297 -51.90 Equatorial Guinea 29.36% -33,914,150 -60.30 Central African Republic 27.64% -5,844,950 -55.60 Chad 24.01% -26,677,028 -58.60 Table 3: Simulations on imports and income variation in the CEMAC resulting from an interregional FTA with the EU Source: UNECA simulations in partial and general equilibrium (Karingi, et al., 2004, p. 51) Whether the other CEMAC+ countries choose to join the existing EU-Cameroon FTA as the EU had once suggested or a new free trade agreement is negotiated, the impact in terms

- 35. 33 of reduction of intra-regional trade among central African countries could offset regional integration in this region. This is an important factor considering that intraregional trade among CEMAC countries is only 2% of their total trade, making it one of the least integrated regions in the world (Prusa, 2011, p. 184). Figure 4: Proportion of CEMAC trade within itself (orange), with Africa (purple) and the Rest of the World (pink) Source: UNCTAD Statistics consolidated in (Karingi, et al., 2004, p. 21) E. The Challenges of multiple institutional regionalisms and multilateralism on EPA negotiations While the CEMAC states have had a more advanced level of cooperation resulting from their common monetary policy6 , finding a common ground with DRC and Sao Tome, and Principe, the other two non-CEMAC members, has proven challenging. First, for Sao Tome and Principe, since it is not a member of the CEMAC, this implied that it was not constrained by the obligations to a CET of the CU. Therefore, in order to effectively coordinate interests in the EPA negotiations, an agreement on trade and customs needed to be concluded between CEMAC and this country. The negotiations towards this are still being undertaken. As for DRC, it started negotiations within the Eastern and Southern Africa regional negotiating configuration from 2002 – 2005 and only joined the Central African negotiating configuration thereafter. This situation which is explained by its membership to several sub regional institutions as explained above raises questions on its commitment to a CET in 6 They all share the FCFA currency,

- 36. 34 Central Africa. In addition, this adherence was relatively late (2 years to the expiry of the WTO’s Cotonou waiver). Its inclusion in Central Africa’s regional configuration has considerably complicated the configuration of the region (…) as it is also a member of SADC and COMESA which negotiate separate EPAs (South Centre, 2007, p. 2). The question therefore arises to what extent the DRC can be committed to the dismantling of tariffs within the CEMAC+ configuration considering its membership in the COMESA and given that the Eastern African negotiating configuration is not inclined to signing the EPA now? The complexities of multiple membership of African countries in several regional blocs as well as the existence of multiple organisations within given zones has been recognised to the extent that in Central Africa, negotiations have been ongoing between CEMAC and ECCAS for a merging of both institutions (Josling, 2011, p. 155). F. The Essence of Timing in Trade Negotiations For Cameroon, timing was essential because having no other available alternative in the case of no deal before 01 January 2008, meant that it would have traded with the EU, its most important partner, under the MFN regime which would have stripped its exports of their competitiveness in the European market. Like in most multilateral settings, these negotiations were extremely slow. Time was not on the side of those countries that decided that trade liberalisation was the appropriate policy to be adopted. As coined by Cameroon’s minister of economy, “negotiations between the EC and the Central African party have been slow, we are looking forward to making progress on them” (Motaze, 2016). In his conceptualisation of the slow pace of multilateral negotiations, (Andriamananjara, 2011, p. 115) states that “the current wave of regionalism is characterised by smaller cross-regional deals, flexibility, selectivity and most important speed. The notion of speed is particularly important. As trade deals drag on, states could find themselves in a losing position when the other states in their negotiating alliance or their interlocutors drag on.” In this type of scenario, states could detach themselves from the alliance and adopt a solitary approach in the defence of their interests as was the case with Cameroon on this issue. It is the obstacles to speed in negotiation that incite Collier and Gunning to criticise any collusive approach to trade negotiation within regional frameworks. According to them, in their three strata approach to trade policy formulation and adoption for developing countries, keeping the locus of authority within the national framework tends to be timelier and thus efficient than engaging in time wasting collusive discriminatory mechanisms.

- 37. 35 Chapter 6: Conclusion and Recommendations A. Conclusion This research set out to elucidate the deficiency of collusion among CEMAC+ countries in their approach towards an inter-regional EPA with the EU party. The inability of these states to agree together on the terms of a FTA with the EU after nearly two decades of negotiations as well as Cameroon’s unilateral approval of an iEPA triggered the interest on this research. By means of qualitative methodology, specifically employing process tracing, this research has provided some important insights regarding intra-regionalism within Central Africa. First, although reciprocal discrimination supersedes reciprocal non-discrimination in the region, it is mainly manifested along the lines of developmental differentiation set out by global economic institutions adopted by the EU rather than on geographical basis within the CEMAC (or CEMAC+). Because these states have higher stakes in their trade relations with the EU and a historic dependency (Babarinde & Wright, 2013, p. 93) than they do amongst themselves, this has left them structurally stratified along the lines of the EU’s differentiating developmental-trade regimes established in conformity to the WTO’s principle of non- discrimination. In plain terms, ACP-LDCs have a greater interest in allying themselves with other LDCs than with non-LDC ACP countries in their quest for continued DFQF access in EU markets. The single GSP- and five EBA- eligible countries of the CEMAC+ negotiating bloc had no interest in establishing reciprocity via an EPA (FTA) with the EU, since like other LDC countries globally, they are guaranteed unilateral market access for which they do not have to reciprocate via domestic liberalisation. The other two ineligible countries chose very opposite paths. While Cameroon unilaterally signed the EPA, Gabon rejected it and has since the expiry of the WTO waiver to SDT in 2008, traded with the EU on MFN basis. The justification of both parties articulates with national interest framed on different models. As stressed by Cameroon’s Minister of Economy, the Cameroonian government’s priority was to maintain the competitiveness of its commodities on the EU market. Gabon on its part, like the other CEMAC+ countries requested for substantial and concrete commitments on development and financial support in view of compensating for the loss of revenue that would result from the elimination of tariffs on EU products. Also, unilateral trade policy dominates collusive trade policy in this region. Although not unique to CEMAC, compromising the CET of the CU as has been perceived in this negotiation is evidence of the heightened intergovernmentalism of the bloc in contrast to the

- 38. 36 expected neo-functionalist cooperation mechanism that should ensure that compromise is achieved within the CEMAC+ negotiations and ultimately resulting in an inter-regional agreement eventually reached with the EU, and expected as such by the latter. The inability of the CEMAC secretariat to curtail any deviations in terms of variability of trade regimes between these countries, and their third-party counterpart, the EU, attests of the fact that the region’s states are much more in control of trade policy which they unilaterally frame based on national interest. Thirdly, regional reciprocal discrimination appears to dominate North-South reciprocal discrimination. For the CEMAC+ states, discriminatory trade with the EU in the form of a FTA must be matched by the EU’s concrete engagement to deliver on the development needs of the region in terms of infrastructure and lifting of supply side constraints. The EU’s hesitation to revise some of its policies such as the CAP, coupled with the projected impacts in terms of trade diversion and deindustrialisation, have heightened such mercantilist bargains. One salient aspect that appears in these negotiations is the asymmetry of institutional capacity and preparedness of the CEMAC secretariat’s inexperience compared to the EU Commission’s experience. While the former has proven deficient in trade collusion policy, the latter has remained cohesive in its approach. In such a situation, regional integration within the Central African bloc could be difficult to achieve particularly in the prevailing context where the gains of liberalisation for developing countries appears to shrink while the cost rises (Gallagher, 2013, p. 143). (Nayyaar, 2007, p. 82) notes that “for a game is not simply about rules. It is also about players. And, if one of the teams or one of the players does not have adequate training and preparation it would simply be crushed by the other. In other words, the rules must be such that newcomers or latecomers to the game, say, the developing countries, are provided with the time and the space to learn so that they are competitive players rather than pushover opponents”. B. Policy Recommendations If an interregional EPA will have to be signed between the EU and CEMAC+ in view of institutionalising a FTA between the two regions, collusion amongst the Central African states will be indispensable. However, the achievement of trade policy cohesion within these countries can only be achieved in due consideration of certain parameters. First, the trade negotiations must incorporate sufficient flexibility that would allow CEMAC+ countries to exclude differentiated sensitive sectors that could be highly impacted