Administrative Law & Judicial Review

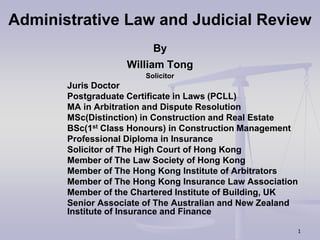

- 1. 1 Administrative Law and Judicial Review By William Tong Solicitor Juris Doctor Postgraduate Certificate in Laws (PCLL) MA in Arbitration and Dispute Resolution MSc(Distinction) in Construction and Real Estate BSc(1st Class Honours) in Construction Management Professional Diploma in Insurance Solicitor of The High Court of Hong Kong Member of The Law Society of Hong Kong Member of The Hong Kong Institute of Arbitrators Member of The Hong Kong Insurance Law Association Member of the Chartered Institute of Building, UK Senior Associate of The Australian and New Zealand Institute of Insurance and Finance

- 2. 2 Contents 1. Hong Kong Legal System 2. Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region 3. Administrative Law 4. Non-Judicial Controls on Government 5. Judicial Review 6. Legal Basis of Judicial Review

- 3. 3 7. The Limits of Judicial Review 8. Remedies 9. Grounds of Judicial Review 10. Human Rights and Judicial Review 11. Application for Judicial Review 12. Issuing a Claim for Judicial Review: Checklist

- 4. 4 What is a legal system? It is a system within a defined geographical area where law is created and enforced. It consists of:- (i) a collection of laws; (ii) process of creating, interpreting, applying and enforcing laws; (iii) institution involved in such process (e.g. the legislature, courts and police force); (iv) personnel involved in the process (e.g. the legislators, judges and lawyers).

- 5. 5 There are two main types of legal systems in the world: civil law and common law legal systems. Civil law legal system emphasizes the importance of statute law (i.e. law made by the legislature). Normally, it has a written constitution. It inclines to adopt an inquisitorial legal method (in which the judges will play a more active role) in the process of a trial. Most European countries such as France, Germany, Italy, etc. belong to this legal system. Common law system emphasizes the importance of case law (i.e. law made by judges). Normally, it does not have a written constitution. It inclines to adopt an adversarial legal method (in which the judges will play a less active role) in the process of a trial. This system is used in most commonwealth countries such as England, Australia, Canada, etc. Hong Kong also belongs to this system.

- 6. 6 What is law? “The written and unwritten body of rules largely derived from custom and formal enactment which are recognized as binding among those persons who constitute a community or state, so that they will be imposed upon and enforced among those persons by appropriate sanctions.” (as per L.B. Curzon) Law governs most aspects of life in a community. Different aspects of law aim to maintain a balance between different competing interests e.g. employment law - employers v employees; tenancy law - landlords v tenants; insurance law – insurers v insureds; constitutional law & administrative law: state v people.

- 7. 7 Rule of law: everyone in the society has to obey the law. No one is supposed to be above the law. In Hong Kong, the concept of separation of powers is adopted. The judiciary, which is independent of the executive branch, is responsible for adjudicating civil and criminal disputes but will not take an active role in the administration of justice. The Department of Justice, being part of the executive branch, has the power to prosecute any person but no power to impose any sentence. The Legislative Council, being a law- making body, has no power to enforce the law. The main purposes of law are to maintain order, achieve justice and promote the common good in the society.

- 8. 8 Criminal Law It concerns the offences against and are punishable by the state (in the context of Hong Kong, i.e. the government of the HKSAR). Title of the proceedings to be used: HKSAR v Defendant (The accused). The HKSAR is to be represented by the Prosecution Division of the Department of Justice. The burden of proof normally rests with the prosecution unless it is shifted by an ordinance.

- 9. 9 The standard of proof required is that of a proof beyond reasonable doubt. Therefore, in a criminal case, any benefit of doubt should be given to the defendant. The main object is to punish convicted offenders by means of a fine, imprisonment or some other forms of punishment such as community service order, probation order, etc. Examples: murder, theft, deception.

- 10. 10 Civil Law It regulates the rights and obligations of persons towards each other e.g. protects private rights; resolves disputes between private citizens. Title of the proceedings to be used: Plaintiff v Defendant. Both the plaintiff and defendant have to prove their case. The standard of proof required is that of a proof on a balance of probabilities. Therefore, if the plaintiff’s case is proved to be more reliable and believable, the court may give judgment in his favour.

- 11. 11 The main object is to win a judgment in the form of money called damages by ordering one party to pay compensation to another or in the form of injunction, specific performance, etc. Examples: law of contract, law of tort, law of agency, insurance law, employment law, etc.

- 12. 12 Public Law - It concerns with the conduct of government and the relations between government and private persons. Examples: constitutional law, criminal law, administrative law. Private law – It concerns with the legal relationship between private individuals, comprises the rules governing relations between private persons or groups of persons. Examples: law of contract, law of tort, company law, law of trust, law of property, law of succession, etc.

- 13. 13 The Development of Hong Kong’s Legal System From 1st July 1997, Hong Kong became a Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China. The HKSAR was established in accordance with the provisions of Article 31 of the Constitution of the People's Republic of China. A high degree of autonomy is promised. The concept of "one country, two systems" is adopted.

- 14. 14 The Sources of Law in Hong Kong PRC Sources (a) Basic Law The National People's Congress of the People’s Republic of China enacted the Basic Law of the HKSAR in 1990. The Basic Law is the constitutional document of the HKSAR and the blueprint for Hong Kong’s future development. It prescribes the systems to be practised in the HKSAR in order to ensure the implementation of the basic policies of the People's Republic of China regarding Hong Kong.

- 15. 15 Article 5 The socialist system and policies shall not be practised in the HKSAR, and the previous capitalist system and way of life shall remain unchanged for 50 years. Article 8 The laws previously in force in Hong Kong, that is, the common law, rules of equity, ordinances, subordinate legislation and customary law shall be maintained. Exceptions: (a) any previous laws that contravene the Basic Law; and (b) any previous laws that are amended by the legislature of the HKSAR.

- 16. 16 Article 18 The laws in force in the HKSAR shall be: (a) The Basic Law of the HKSAR (b) The laws previously in force in Hong Kong as provided for in Article 8 of this Law, and (c) The laws enacted by the legislature of the HKSAR. Article 19 The HKSAR shall be vested with independent judicial power, including that of final adjudication.

- 17. 17 (b) National Laws of PRC applicable to HK Article 18 Basic Law National laws shall not be applied in the HKSAR except for those listed in Annex III: (i) Resolution on the Capital, Calendar, National Anthem and National Flag;國都、紀年、國歌、國旗的決議 (ii) Resolution on the National Day;國慶日的決議 (iii) Order on the National Emblem;國徽的命令 (iv) Declaration on the Territorial Sea;關於領海的聲明 (v) Nationality Law;國籍法 (vi) Regulations Concerning Diplomatic Privileges and Immunities.外交特權與豁免條例

- 18. 18 UK Sources – The Common Law and Rules of Equity Common law has its origin in UK. Historically, at the time of Norman Conquest in 1066, different localities in England had different local customary rules. The King at that time asked the judges to develop unified rules of law which applied throughout the kingdom. These rules were later developed into a system of common law and administered by the common law courts. However, the procedures of common law were unsatisfactory in that the plaintiff might not obtain redress for grievances because of some minor procedural. Moreover, in some aspects, common law was too rigid and inflexible.

- 19. 19 Later the King asked the Chancellor to deal with the grievances and the rules on which the Chancellor decided the case were based on justice and fairness. The principles of equity were later developed and administered by the Court of Chancery. Reports of judgments handed down by judges have, since at least the 15th century, established in detail the legal principles regulating the relationship between state and citizen, and between citizen and citizen. These 2 different sets of rules were administered in 2 different courts in UK until the 19th century.

- 20. 20 There are a number of differences between common law and equity: (i) They have different origins. Common law was developed by the common law courts while equity was developed by the Court of Chancery. (ii) Common law remedies (e.g. damages) are granted as of right whereas equitable remedies (e.g. specific performance) are discretionary. (iii) Common law is a complete system of law while equity is only supplementary.

- 21. 21 (iv) The time-limits for common law rights are laid down in the Limitation Ordinance while equitable rights must be applied for promptly. (v) When there is a conflict between common law and equity, equity will prevail. Judicial precedent There are now some hundreds of thousands of reported cases in common law jurisdictions which comprise the common law. Because it is not written by the legislature but by judges, it is also referred to as "unwritten" law. Judges seek these principles out when trying a case and apply the precedents to the facts to come up with a judgment.

- 22. 22 Hong Kong Sources Local Legislation: the Legislative Council in the HKSAR is the most important law making body in Hong Kong. The laws passed by it are called Ordinances. Ordinances govern most aspects of life in Hong Kong. Subsidiary Legislation: the Hong Kong Legislature may delegate law-making powers to other bodies, e.g. the MTR is empowered to make the MTR By-Laws under the Mass Transit Railway Ordinance. The laws made by those bodies are called rules, regulations, by-laws, etc. and their main functions are to supplement ordinances. Decisions of the Hong Kong Courts: decisions made by superior courts are binding on inferior courts in Hong Kong.

- 23. 23 Traditional Sources: Customary Chinese Law Chinese law and custom is to be found in the Codes of the Qing Dynasty as supplemented by customary rules. Chinese customary law has been applied in relations to land in the New Territories e.g. under New Territories Ordinance (Cap 97), family law and succession, etc.

- 24. 24 THE HONG KONG LEGAL MACHINE The Judiciary It is responsible for the administration of justice in Hong Kong. The Chief Justice of the Court of Final Appeal is the head of the Judiciary.

- 25. 25 The Courts of Law in Hong Kong The Court of Final Appeal It is the highest appellate court in Hong Kong. It only has appellate jurisdiction but no original jurisdiction. It normally hears appeals on civil and criminal matters from the Court of Appeal. However, in some circumstances, the Court of Final Appeal may hear appeals from the Court of First Instance directly. It has unlimited civil and criminal jurisdiction but no jurisdiction over acts of state such as defence and foreign affairs.

- 26. 26 In civil matters: (a) monetary claims involved must be not less than HK$1 million or (b) matters of public importance. In criminal matters: normally more serious offences heard in the Court of First Instance will be appealed to the Court of Final Appeal. It comprises five judges – - the Chief Justice, - three permanent judges, and - one non-permanent Hong Kong judge or one judge from another common law jurisdiction.

- 27. 27 The High Court It consists of the Court of Appeal and the Court of First Instance. The Court of Appeal of the High Court It hears appeals on civil and/or criminal matters from the Court of First Instance, District Court and Lands Tribunal. It has unlimited civil and criminal jurisdiction. It normally comprises three judges.

- 28. 28 The Court of First Instance of the High Court It has unlimited jurisdiction in both civil and criminal matters. It has both original and appellate jurisdiction. It exercises civil jurisdiction (normally by one judge without jury) in disputes relating to breach of contract, tort, bankruptcy, company winding-up, intellectual property, probate and mental health matters, etc.

- 29. 29 Most serious criminal offences, such as murder, manslaughter, rape, armed robbery, trafficking in large quantities of dangerous drugs and complex commercial frauds are tried by a judge of the Court of First Instance together with jury. It hears appeals from the Magistrates’ Courts and other tribunals (except the Lands Tribunal).

- 30. 30 District Court Civil jurisdiction It hears monetary claims up to $1,000,000 or, Where the claims are for recovery of land, the annual rent or ratable value does not exceed $240,000. Criminal jurisdiction It tries more serious cases, with the exception of murder, manslaughter and rape. It may sentence offenders to imprisonment for a maximum of 7 years.

- 31. 31 The District Court has been assigned special jurisdiction to hear cases relating to employees’ compensation under the Employees Compensation Ordinance and cases for discrimination under various anti-discrimination ordinances The Family Court, which is part of the District Court, deals with family-related matters such as divorce, maintenance, custody, etc. Appeals will go to the Court of Appeal.

- 32. 32 The Magistrates’ Courts Permanent Magistrates exercise criminal jurisdiction over a wide range of summary offences including petty theft, common assault, road traffic offences, possession of drugs. The maximum sentencing power of a Permanent Magistrate is 2 years’ imprisonment (or 3 years’ imprisonment if two or more consecutive sentences are imposed) and a fine of $100,000.

- 33. 33 Where an accused is charged with an indictable offence, he will be brought in the first place before a Permanent Magistrate for committal proceedings(初級 偵訊). The function of the Magistrate is not that of finding the accused guilty or not guilty but to determine whether a prima facie case has been made, and if this is the case, the accused will be transferred to the District Court or the Court of First Instance for a formal trial. A Magistrate has power to issue a warrant for the apprehension of any person or to grant or refuse bail.

- 34. 34 Some minor offences such as hawking, traffic contraventions and littering are heard by Special Magistrates who do not have the power to impose imprisonment. Their jurisdiction is limited to a maximum fine of $50,000. The Juvenile Court has jurisdiction to hear charges against children (aged under 14) and young persons (aged between 14 and 16) for any offences other than homicide. Appeals to the Magistrate Court’s decisions go to the Court of First Instance of the High Court.

- 35. 35 The Appeal System The Court of Final Appeal hears appeals on civil and criminal matters from the Court of Appeal and Court of First Instance. The Court of Appeal hears appeals on civil and/or criminal matters from the Court of First Instance, District Court and Lands Tribunal. The Court of First Instance hears appeals on civil and/or criminal matters from the Magistrate's Court, Labour Tribunal and Small Claims Tribunal.

- 36. 36 The Jury System The most serious criminal offences are tried by a judge of the Court of First Instance, sitting with a jury consisting of seven or, where a judge so orders, nine. It is the jury which decides whether the accused is guilty or not guilty and a majority vote is required. The system of jury may be used in some civil cases such as libel. Also if a coroner decides to hold an inquest with a jury, a jury of three will be appointed.

- 37. 37 THE DOCTRINE OF JUDICIAL PRECEDENT 1. Introduction The custom of following already decided cases is called the doctrine of judicial precedent or stare decisis (Latin phrase meaning to stand by previous decisions). In certain circumstances the judge has no option but to apply the law as previously pronounced whether he agrees with it or not.

- 38. 38 2. Case law 2.1 Ratio decidendi: “the reason for decision”. It consists of 3 parts: - material facts of the case; - statement of law applied to the legal problems disclosed by the facts upon which the decision is based; and - final decision. 2.2 Obiter dictum: “thing said by the way” Statement of law made by the way, not based on the facts as found. Only the ratio decidendi of a case is strictly binding, obiter dictum is only persuasive.

- 39. 39 3. The ranking of courts and the doctrine of judicial precedent The decisions made by higher courts are normally binding on lower courts. The decisions made in tribunals have no binding effect. However, all decisions made by the court are persuasive even though they are not binding.

- 40. 40 The Process of Legislation Initially, there will be consultation with interested parties. A bill will be prepared by the Law Drafting Division of the Department of Justice and submitted to the Executive Council for discussion. Normally, approval from the Chief Executive in Council is needed to introduce a bill into the Legislative Council. However, any member of the Legislative Council is also entitled to introduce a private bill. The bill will be published in the Government Gazette for further consultation.

- 41. 41 The bill will be given a short title (setting out the name of the bill), a long title (setting out the purposes of the bill in general terms) and an explanatory memorandum (stating the contents and objects of the bill in non- technical language). The bill shall be presented in the Chinese and English languages. First Reading is a mere formality. The clerk reads the short title of the bill after which the Council shall be deemed to have ordered the bill to be set down for a second reading. Second Reading: a debate is held during which legislators can voice their opinions. Then, there will be a vote to decide if the bill should be passed.

- 42. 42 If the bill is defeated, no further proceedings will be taken. If the bill is passed, it may go through a committee stage during which more details will be worked out. The bill will then be proceeded to Third and Final Reading. A copy of every bill passed by the Legislative Council shall be submitted to the Chief Executive for his signature and the bill will formally become an ordinance.

- 43. 43 An ordinance shall be published in the Gazette again and it generally commences at the beginning of the day on which it is published or commences on a day to be announced. Law enacted by the legislature of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region must be reported to the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress for record. The reporting for record shall not affect the entry into force of such law. (Article 17 of the Basic Law)

- 44. 44 The Delegated Legislation Legco is not able to deal directly or specifically with all of the details of its statutes. A great deal of legislation is made under delegated powers called subsidiary or delegated or subordinate legislation. The ‘parent’ ordinance gives powers to some institutes to make the delegated legislation. For example, the Companies Ordinance provides that the Chief Justice may, with the approval of Legco, make rules for the winding up of companies.

- 45. 45 THE INTERPRETATION OF LEGISLATION 1. Problems associated with interpreting statutes Language is in some respects an imperfect means of communication and sometimes the intention of legislature is not completely clear in the legislation which it passes. The function of judges in relation to legislation is to apply and interpret it in the case before them.

- 46. 46 Statutory aids to interpretation The Interpretation and General Clauses Ordinance Section 7: ‘the male includes the female gender, and vice versa’ ‘writing includes printing, photography and other methods’ ‘person includes corporations’ ‘singular includes the plural, and vice versa’ Section 19: An Ordinance shall be deemed to be remedial and shall receive such fair, large and liberal construction and interpretation as will best ensure the object of the Ordinance is attained according to its true intent, meaning and spirit.

- 47. 47 Common Law Approaches (a) The literal rule Where words of an Ordinance are themselves plain and unambiguous, no matter how unjust they might be, they must be interpreted according to their literal and grammatical meaning. The duty of the judges is to explain the words in their natural and ordinary sense, even if the result appears to be contrary to the intention of the legislature.

- 48. 48 Common Law Approaches (b) The golden rule Where the statute permits of two or more interpretations, the court must adopt that interpretation to avoid any “manifest absurdity” and the language may be varied or modified only so much as is to remove the absurd result. (c) The mischief rule The courts try to find out the true reasons of the legislation. The courts will ask the following questions: (i) what was the common law before the statute; (ii) what was the mischief for which common law did not provide; (iii) what remedy has Parliament resolved so as to cure it; and (iv) what is the true reason of that remedy?

- 49. 49 Common Law Approaches (d) The ejusdem generis rule Where general words follow particular words, the general words must be taken as referring to things of the same kind as the particular words, e.g. "dogs, cats and other animals" – the phrase “other animals” should not be interpreted to include lions and tigers which are not domestic animals. Similarly, a reference to “house, office, room or other place” was held not to include an outdoor racecourse, for “other place” created a genus of indoor places only.

- 50. 50 The Department of Justice The Department of Justice plays a significant role in our legal system. The Department gives legal advice to other bureaux and departments of the Government, represents the Government in legal proceedings, drafts government bills, makes prosecution decisions, and promotes the rule of law. It is an important policy objective of the Department to enhance Hong Kong's status as a regional centre for legal services and dispute resolution.

- 51. 51 Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

- 52. 52 Government in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region The Executive – The provisions of the Basic Law ensure a strong Chief Executive who would take on a role much like that previously held by the Governor of Hong Kong. Under the Basic Law, the Chief Executive is to hold office for a term of not more than five years and is appointed by the Central People’s Government. The Basic Law also provides that the Chief Executive is to be assisted by an Executive Council. It exists to assist the Chief Executive in making policy decisions and should indeed be consulted by the Chief Executive before she makes any major policy decisions. The Chief Executive should also consult the Council before he introduces Bills into the Legislative Council.

- 53. 53 The Legislature – The main work of the Legislative Council under the Basic Law is to make and amend legislation, to examine and approve budgets presented by the government, to approve taxation and public expenditure, to raise questions concerning the work of the government, to engage in debate on matters of public interest. The Basic Law provides for ‘check and balance’ mechanisms between the executive and the legislature. For example, it is provided that if the Chief Executive refuses to assent to a Bill passed by LegCo, he may refer it back for reconsideration. If LegCo then passess the original Bill again by a two-thirds majority, the Chief Executive must either sign the Bill into law or dissolve LegCo. If LegCo is dissolved and the subsequently elected LegCo again passes the Bill by a two-thirds majority, the Chief Executive must either sign it or resign.

- 54. 54 The Judiciary – The Basic Law resulted in significant changes to the judicial branch of power. Article 81 established a Court of Final Appeal within Hong Kong, replacing the privy Council in London as the final court of appeal for Hong Kong; and Art 82 gave the Court of Final Appeal the power of final adjudication. Furthermore, the Basic Law, in Art 85, explicitly maintains the principle of an independent judiciary. In terms of appointment and tenure of judges, Art 88 of the Basic Law has provided that the Chief Executive has the power to appoint judges but he may do so only on the recommendation of an independent commission composed of local judges, persons from the legal profession and eminent persons from other sectors.

- 55. 55 However, these provisions have to be balanced against Art 158 which confers the power of final interpretation of the Basic Law in matters concerning relations between the Hong Kong SAR and PRC to the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress (NPCSC). This latter provision, especially when it is given a broad interpretation, may be said to have potential to result in a considerable diminution of the Hong Kong courts’ power of final adjudication and at the same time invite the substitution of the political perspective of the NPCSC for the judicial perspective of the Hong Kong judiciary.

- 57. 57 Administrative law is the law that provides the legal power and the legal duties of individual public bodies and public authorities, e.g. local authority powers and duties, of government departments. Administrative law is the legal framework within which public administration is carried out. It derives from the need to create and develop a system of public administration under law. Since administration involves the exercise of power by the executive arm of government, administrative law is of constitutional and political, as well as juridical, importance.

- 58. 58 There is no universally accepted definition of administrative law, but rationally it may be held to cover the organization, powers, duties, and functions of public authorities of all kinds engaged in administration; their relations with one another and with citizens and nongovernmental bodies; legal methods of controlling public administration; and the rights and liabilities of officials. One of the principal objects of administrative law is to ensure efficient, economical, and just administration. Red light theories – Red light theories are those which see the aim of administrative law as being to curb state activity so as to protect the individual. Red light theories believe (1) that law is superior over politics; (2) that the administrative state needs to be kept in check; and (3) the best way to do this is through rule based adjudication in the courts.

- 59. 59 Green light theories – Green light theories see administrative law as existing to help the state meet certain policy objectives. They emphasize the role allotted to political institutions, i.e. taking a ‘functionalist approach’ to the allocation of functions. They want to encourage efficiency in the governing process. It basically comes down not to resisting interventionism, but to make the policy efficient and provide justice for individuals. Green light theories say (1) that law is merely a type of political discourse and is not superior to administration; (2) that public administration is not a necessary evil but a positive good; (3) that administrative law is not to stop bad practices but to promote and facilitate good administrative practices and that rule based adjudication is not necessarily the best way to do this, and (4) that liberty is to be promoted.

- 60. 60 In reality, there are many shades in between red and green light theories, and most people occupy a middle ground. The focus of the discussion on red and green light theories may give the impression that legal systems can be described in such definite terms. However, there is also a view put forward by some academics that systems will usually display characteristics of both red and green light theories. These kind of theories are categorized as amber light theories. Amber light theorists say that (1) law is superior to politics – same as red; (2) that the state can successfully be limited by law, but that it ought to be given a controlled area of discretion; (3) that the best method of control is through broad judicial principles such as legality; and (4) that liberty amounts to the protection of specific human rights.

- 61. 61 Moving beyond the purposes of control and facilitation, there are other purposes behind administrative law that help shape its scope and development: (1) administrative law serves to command the performance of public functions. This will often be the case where an Ordinance places a legal duty on a decision-maker to meet certain obligations. (2) administrative law serves the purpose of holding the executive accountable for the decisions they make. (3) administrative law provides a mechanism for participation in the processes of government. (4) and perhaps the most important for an aggrieved resident, administrative law serves to provide remedies for wrongs committed by public authorities.

- 63. 63 Principal Officials Accountability System (POAS) It is a system whereby all principal officials, including the Chief Secretary for Administration, Financial Secretary, Secretary for Justice and head of government bureaux would no longer be politically neutral career civil servants. Instead, they would all be political appointees chosen by the chief executive. Principal officials under the accountability system will accept total responsibility and in an extreme case, they may have to step down for serious failures relating to their respective portfolios. They may also have to step down for grave personal misconduct or if they cease to be eligible under the Basic Law.

- 64. 64 Access to Information Access to information is fundamental for promoting accountability and transparency on the part of the executive. This is regulated through the code on Access to Information introduced in March 1995. The Code on Access to Information provides a formal framework for access to information held by government departments. It defines the scope of information that will be provided, sets out how the information will be made available either routinely or in response to request, lays down procedures governing its release, as well as procedures for review or complaint.

- 65. 65 Public consultations and engagement If conducted properly and with proper access to an appropriate cross-section of the public and relevant stakeholders, the public consultation process can: (1) Improve the overall decision-making process through input from a wider range of sources than are available within the government. (2) Improve the participative legitimacy of decisions made on key policy areas. (3) Improve the chances of a more rounded and researched decision a the end of the process.

- 66. 66 Statutory Advisory Bodies In certain areas of government there exist statutory and advisory bodies which provide advisory support to the government. These bodies may have been created by statute or by the executive body they are assisting: By statute – For example, the Antiquities Advisory board 古物諮詢委員會 is established pursuant to section 17 of the Antiquities and Monuments Ordinance古物及古蹟條 例(Cap. 53) provides the Antiquities Authority with advice on the historical grading of a building or site. By executive bodies they advise –Telecommunications Regulatory Affairs Advisory Committee 電訊規管事務諮詢 委員會 of the telecommunications Authority and the Transport Advisory Committee 交通諮詢委員會 of the Transport and Housing Bureau.

- 67. 67 Tribunals委員會 Tribunals are intended to make up for certain limitations that affect the operation of judicial review. Judicial review can be expensive and time-consuming to obtain. Judges can only review the legality or lawfulness of a decision and not the merits of the decision, and at the conclusion of a judicial review the judge must remit the decision back to the original decision-maker to reconsider. Tribunals are intended to provide a less costly and less time-consuming alternative to judicial remedies through a simpler procedure. In addition, tribunals are intended to provide a specialized form of redress as tribunals tend to be staffed by specialists in various areas of government and not just lawyers.

- 68. 68 Tribunals Two main categories of tribunals: general and specialist. The main general tribunal is the Administrative Appeals Board 行政上訴委員會 which hears appeals against government decisions made under a variety of legislation. Key specialist tribunals include the Immigration Tribunal, the Social Security Appeals Board社會保障上訴 委員會and the Appeal Board Panel (Town Planning)上訴 委員團﹝城市規劃﹞.

- 69. 69 Office Of The Ombudsman 申訴專員公署 Section 7(1)(a)(ii) of The Ombudsman Ordinance empowers The Ombudsman to initiate investigations of his own volition even no complaint has been received if he considers that any person may have sustained injustice in consequence of maladministration of an organisation under his purview. Such investigations are called direct investigations. Under the Ordinance, The Ombudsman has a wide range of investigative powers: conducting inquiries, obtaining information and documents, summoning witnesses and inspecting premises of organisations under complaint.

- 70. 70 Office Of The Ombudsman The Ombudsman has powers to: (1) investigate complaints from aggrieved persons about maladministration by the Government departments/agencies and public bodies. (2) investigate complaints against Government departments/agencies for non-compliance with the Code on Access to Information. (3) initiate direct investigation, of his volition, into issues of potentially wide public interest and concern.

- 71. 71 Office Of The Ombudsman Direct Investigation is a proactive approach to problems of public interest and concern. It aims at: (1) following through matters with systemic or widespread deficiencies which investigation of a specific complaint may not resolve. (2) nipping problems in the bud. (3) resolving repeated complaints by addressing the fundamental problems which may not be the subject of any complaint but which may be the underlying reasons for deficiencies.

- 72. 72 Office Of The Ombudsman A direct investigation may be prompted by topical issues of community concern, implementation of new or revised Government policies or repeated complaints on particular matters. The main considerations for launching a direct investigation include: (1) whether the matter involved is of public interest and concern. (2) whether a complaint will otherwise not be actionable, e.g. it is made anonymously or not by an aggrieved person, where the matter is nevertheless of significant concern to The Ombudsman because of the magnitude or seriousness of the maladministration that may be involved.

- 73. 73 Office Of The Ombudsman (3) whether the time is opportune, weighing against the consequences of not doing so and the public expectations of this Office. (4) whether there is duplication of the efforts of other organisations.

- 74. 74 Office Of The Ombudsman While The Ombudsman’s investigation shall not affect any action taken by the organisation under complaint or the organisation's power to take further action with respect to any decision which is subject to the investigation, the Ombudsman may report his findings and make recommendations for redress or improvement to the organisation. Heads of organisations have a duty to report at regular intervals their progress of implementation of The Ombudsman's recommendations.

- 76. 76 Judicial Review is a review of administrative decisions or determinations made by someone who has the power and authority to make a certain set of decisions of determinations. Judicial review is a procedure by which the Court of First Instance of the High Court exercises its supervisory jurisdiction over the activities of administrative bodies and inferior courts. The administrative bodies concerned are usually government departments and those public bodies which were set up according to certain ordinances. The party who applies for a judicial review is called "the Applicant" and the party who made the decision under dispute is called "the Respondent".

- 77. 77 The first important note is that judicial review does not aim at reviewing the merits of an administrative decision. Instead, the court will review the relevant decision- making process . In other words, the court will not examine whether the decision under challenge is right or wrong, but it will check whether there was any error made during the decision-making process. The second note is that the decision under review must affect the public interest . If the subject decision only undermines your own interest, or it is only a personal dispute between you and the decision-maker, the court will reject your application. An example of a personal dispute would be an argument between you and the decision-maker in relation to a contract term.

- 78. 78 The third note is that a judicial review is normally brought to the court on at least one of the following grounds: The decision was made by a person who does not have the relevant statutory authority. The decision was made under an improper or incorrect procedure. (For example, the decision-maker did not observe the procedural rules as written in a particular ordinance.) The decision was unreasonably made. (For example, the decision-maker failed to take into account a relevant matter when making the decision).

- 80. 80 The legal basis has a major bearing on the scope of judicial review. If the legal basis for the court’s role necessarily implies a limited role for judicial review, then the courts would be unable to subject decision-makers to a searching standard of scrutiny. If, by contrast, the legal basis imply a broad role for the courts, then the courts would be free to develop judicial review principles in a way that could lead to considerable legal restriction on a decision-maker’s discretion. Linked to the scope of judicial review, the legal basis should also indicate the method by which the court approaches the task of review. Identifying the legal basis for judicial review is important in order to provide a justification for the court’s role.

- 81. 81 The ultra vires doctrine The legislative intention approach, known as the ultra vires doctrine, represents the proposition that a decision- maker, on whom legislation has conferred legal powers, must not exceed these powers. In determining whether the decision-maker exceed their powers, the courts will ascertain from an examination of the legislative intent the applicable principles that define the scope of these legal powers. Common amongst these principles: a decision-maker cannot act in bad faith, act with an improper statutory purpose, ignore relevant considerations, take into account irrelevant considerations, or behave irrationally.

- 82. 82 Problems with the ultra vires doctrine First, the ultra vires doctrine is premised on there being ascertainable legislative standards to guide the court in establishing whether a decision-maker acted beyond their powers. The difficulty, however, is that many ordinances are drafted in vague and imprecise terms. Often, statutory provisions are of such open texture that they do not place any limits on the court’s role. Second, the ultra vires doctrine is unable to account for the development of judicial review over time. If the courts are applying the intention of the legislature in each case, then what accounts, for example, for the sudden development of substantive legitimate expectations or proportionality review?

- 83. 83 Problems with the ultra vires doctrine Third, the ultra vires doctrine does have some semblance of truth with respect to how the courts supervise the acts and decisions of statutory bodies exercising statutory powers. However, there are significant areas of administrative activity which do not derive from a statutory source. In this regard, the courts have also applied principles of judicial review to (a) non-statutory bodies and (b) bodies exercising non-statutory powers. Fourth, if the courts are really applying legislative intention, then how can they justify their disregard of those statutory clauses that seek to ‘oust’ judicial review.

- 84. 84 The common law theory of judicial review It is against the backdrop of the criticism of the ultra vires doctrine that various commentators have developed an alternative, competing foundations for judicial review: one based on the common law methodology of judicial decision-making and common law values. The common law principles are justified by reference to the rule of law. Implicit in the rule of law are substantive ideals such as justice, fairness and respect for rights.

- 85. 85 Further development to the common law theory of judicial review (1) The rights-based approach – the judicial intervention is no longer premised on the idea that the courts are simply applying the legislative will. Their role is to articulate principles, which should guide the exercise of administrative action. A common element of a rights- based approach is that the courts should whenever possible interpret the exercise of administrative discretion to be in conformity with fundamental rights.

- 86. 86 Further development to the common law theory of judicial review (2) Abuse of power When it is accepted that the public authority had the power, however there is something about the doing it in an individual circumstance that constitutes an abuse of the power. There has three grounds of review: (a) the exercise of power for an improper purpose (b) taking account of the irrelevant considerations or failing to take into account of relevant ones and (c) it must be true that no reasonable person, who was acting in a reasonable manner at the moment in question, could have possibly performed the action.

- 87. 87 Further development to the common law theory of judicial review (3) Fairness (a) Procedural fairness – The fundamental requirements of procedural fairness are that a hearing or other appropriate procedure will be afforded before any decision is made. (b) Substantive fairness – this concerns the principle of legitimate expectation. If a representation has been expressly made that a benefit of a substantive nature will be granted or if any person is already in receipt of any benefit, it will be continued and will not be substantially varied to the disadvantage of the recipient.

- 89. 89 Constitutional Limits on Judicial Review Act of State Under Article 19 of the Basic Law: “The courts of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region shall have no jurisdiction over acts of state such as defence and foreign affairs.” The rationale for excluding acts of state from judicial review is that they are matters of policy and not of law, with the executive in a better position than the courts to determine where the balance lies.

- 90. 90 Constitutional Limits on Judicial Review Prerogative of mercy Article 48(12) of the Basic Law empowers the Chief Executive ‘To pardon persons convicted of criminal offences or commute their penalties.’ This prerogative power can have the effect of relieving a prisoner from the punishment, either freely or conditionally, which may follow criminal conviction. This prerogative is used as a means of correcting miscarriages of justice when the appellate courts could not, such as where exculpatory evidence was inadmissible, or for summary convictions, which at that time circumstances where the criminal trial and appeal system produces a result that the public interest cannot sustain.

- 91. 91 Constitutional Limits on Judicial Review Policy formulation Article 62 of the Basic Law confers constitutional authority on the executive ‘To formulate and implement policies’, which includes the power to ‘To conduct administrative affairs’. In formulating policy, especially that which has broad social and economic implications, the executive will have to take into account a wide range of factors and interests to arrive at the chosen policy.

- 92. 92 Statutory Limits on Judicial Review Time limit clauses Time limit clauses serve the purpose of limiting the period of time to seek a remedy for a public law breach. If the applicant failed to seek judicial redress within the required time then their application will be statute- barred. An application for judicial review must be made promptly and in any event within three months after the grounds to make a claim first arose. Yet, time limit clauses that appear in legislation will often shorten this period, taking into account the needs for expeditious and final decisions in a particular area of public decision-making. For example, there is a seven- day statutory time limit to lodge a petition to challenge the validity the Chief Executive’s election.

- 93. 93 Statutory Limits on Judicial Review Ouster clauses – An ouster clause is a statutory provision that seeks to remove the court’s power to review and grant remedies. Examples: Housing Ordinance (Cap. 283), Section 19(3): No court shall have jurisdiction to hear any application for relief by or on behalf of a person whose lease has been terminated under subsection (1) in connection with such termination. Protection of Wages on Insolvency Ordinance (Cap. 380), Section 20: No decision of the Commissioner or the Board made in exercise of any discretion under this part shall be challenged in any court.

- 94. 94 Remedies

- 95. 95 Certiorari (Quashing Order) A quashing order nullifies a decision which has been made by a public body. The effect is to make the decision completely invalid. Such an order is usually made where an authority has acted outside the scope of its powers (‘ultra vires’). The most common order made in successful judicial review proceedings is a quashing order. If the court makes a quashing order it can send the case back to the original decision maker directing it to remake the decision in light of the court’s findings. Or, very rarely, if there is no purpose in sending the case back, it may make the decision itself.

- 96. 96 Prohibition (Prohibiting Order) A prohibiting order is similar to a quashing order in that it prevents a tribunal or authority from acting beyond the scope of its powers. The key difference is that a prohibiting order acts prospectively by telling an authority not to do something in contemplation. Examples of where prohibiting orders may be appropriate include stopping the implementation of a decision in breach of natural justice, or to prevent a local authority licensing indecent films, or to prevent the deportation of someone whose immigration status has been wrongly decided.

- 97. 97 Mandamus (Mandatory Order) A mandatory order compels public authorities to fulfil their duties. Whereas quashing and prohibition orders deal with wrongful acts, a mandatory order addresses wrongful failure to act. A mandatory order is similar to a mandatory injunction as they are orders from the court requiring an act to be performed. Failure to comply is punishable as a contempt of court. A mandatory order may be made in conjunction with a quashing order, for example, where a local authority’s decision is quashed because the decision was made outside its powers, the court may simultaneously order the court to remake the decision within the scope of its powers.

- 98. 98 Declaration A declaration is a judgment by the Administrative Court which clarifies the respective rights and obligations of the parties to the proceedings, without actually making any order. Unlike the remedies of quashing, prohibiting and mandatory order the court is not telling the parties to do anything in a declaratory judgment. For example, if the court declared that a proposed rule by a local authority was unlawful, a declaration would resolve the legal position of the parties in the proceedings. Subsequently, if the authority were to proceed ignoring the declaration, the applicant who obtained the declaration would not have to comply with the unlawful rule and the quashing, prohibiting and mandatory orders would be available.

- 99. 99 Injunction An injunction is an order made by the court to stop a public body from acting in an unlawful way. Less commonly, an injunction can be mandatory, that is, it compels a public body to do something. Where there is an imminent risk of damage or loss, and other remedies would not be sufficient, the court may grant an interim injunction to protect the position of the parties before going to a full hearing. If an interim in injunction is granted pending final hearing, it is possible that the side which benefits from the injunction will be asked to give an undertaking that if the other side is successful at the final hearing, the party which had the benefit of the interim protection can compensate the other party for its losses.

- 100. 100 Damages Damages are available as a remedy in judicial review in limited circumstances. Compensation is not available merely because a public authority has acted unlawfully. For damages to be available there must be a recognised ‘private’ law cause of action such as negligence or breach of statutory duty .

- 101. 101 Discretion The discretionary nature of the remedies outlined above means that even if a court finds a public body has acted wrongly, it does not have to grant any remedy. Examples of where discretion will be exercised against an applicant may include where the applicant’s own conduct has been unmeritorious or unreasonable, for example where the applicant has unreasonably delayed in applying for judicial review, where the applicant has not acted in good faith, where a remedy would impede the an authority’s ability to deliver fair administration, or where the judge considers that an alternative remedy could have been pursued.

- 104. 104 What is procedural fairness? Procedural fairness is concerned with the procedures used by a decision-maker, rather than the actual outcome reached. It requires a fair and proper procedure be used when making a decision. The rules of procedural fairness do not need to be followed in all government decision-making. They mainly apply to decisions that negatively affect an existing interest of a person or corporation. For instance, procedural fairness would apply to a decision to cancel a licence or benefit; to discipline an employee; to impose a penalty; or to publish a report that damages a person’s reputation. Procedural fairness also applies where a person has a legitimate expectation. It protects legitimate expectations as well as legal rights. It is less likely to apply to routine administration and policy-making.

- 105. 105 The duty to accord procedural fairness consists of three key rules: (1) the fair hearing rule – which requires a decision- maker to accord a person who may be adversely affected by a decision an opportunity to present his or her case; (2) the rule against bias – which requires a decision- maker not to have an interest in the matter to be decided and not to appear to bring a prejudiced mind to the matter; and (3) the "no evidence" rule – which requires a decision to be based upon logically probative evidence.

- 106. 106 When should the rules of procedural fairness be observed? There is a presumption in law that the rules of procedural fairness must be observed in exercising statutory power that could affect the rights, interests or legitimate expectations of individuals. However, it is good practice to observe these rules whether or not the power being exercised is statutory. If action being taken by a public official or by or on behalf of a public sector agency will not directly affect a person’s rights or interests, there is no obligation to inform the other person of the substance of any allegations or other matters in issue. However, if an investigation will lead to findings and recommendations about the matter, the investigator should provide natural justice to the person against whom allegations have been made. Similarly, the person who ultimately makes a decision on the basis of the investigation report must also provide natural justice, by allowing the person adversely commented upon to make submissions regarding the proposed decision and sanction.

- 107. 107 What are the rules of procedural fairness? Any person who decides any matter without hearing both sides, though that person may have rightly decided, has not done justice. Any person whose rights, interests or legitimate expectations will be affected by a decision or finding is entitled to an adequate opportunity of being heard. In order to properly present their case, the person is entitled to know the grounds on which that decision or finding is to be taken. Depending on the circumstances which apply, natural justice may require a decision-maker to: • inform any person: – whose interests are or are likely to be adversely affected by a decision, about the decision that is to be made and any case they need to make, answer or address – who is the subject of an investigation (at an appropriate time) of the substance of any allegations against them or the grounds for any proposed adverse comment in respect of them.

- 108. 108 • provide such persons with a reasonable opportunity to put their case, or to explain to the decision-maker, whether in writing, at a hearing or otherwise, why contemplated action should not be taken or a particular decision should or should not be made. • consider those submissions. • make reasonable inquiries or investigations and ensure that a decision is based upon findings of fact that are in turn based upon sound reasoning and relevant evidence. • act fairly and without bias in making decisions, including ensuring that no person decides a case in which they have direct interest. • conduct an investigation or address an issue without undue delay.

- 109. 109 Benefits for persons whose rights or interests may be affected Procedural fairness allows persons whose rights or interests may be affected by decisions the opportunity: (a) to put forward arguments in their favour. (b) to explain why proposed action should not be taken. (c) to deny allegations. (d) to call evidence to rebut allegations or claims. (e) to explain allegations or present an innocent explanation. (f) to provide mitigating circumstances.

- 110. 110 Benefits for investigators and decision-makers While procedural fairness is, at law, a safeguard applying to the individual whose rights or interests are being affected, an investigator or decision-maker should not regard such obligations as a burden or impediment to an investigation or decision-making process. Procedural fairness can be an integral element of a professional decision-making or investigative process – one that benefits the investigator or decision-maker as well as the person whose rights or interests may be affected.

- 111. 111 Fair Hearing Rule The hearing rule requires a decision-maker to inform a person of the case against them and provide them with an opportunity to be heard. The extent of the obligation on the decision-maker depends on the relevant statutory framework and on what is fair in all the circumstances. Components of a ‘fair hearing’: 1. Right to notice; 2. Right to present case and evidence or right for a ‘hearing’; 3. Right to know the evidence against him; 4. Right to challenge the opposing case; 5. Legal Representation; and 6. The duty to provide adequate reasons.

- 112. 112 Right to notice The parties likely to be affected by a decision are given sufficient advanced notice of any proposed action taken by the authority. The basic principle underlying the notice requirement is that persons affected by decisions should not be taken by surprise. Notice is required so that affected persons can at least attend the hearing, and if they wish to argue their case. This entails knowing the case against them or their interests, including the disclosure of all materials that are relevant to the charges made against them. The notice should be sufficiently clear so that the affected parties can prepare their case, which may include disclosure of all documents pertinent to the authority’s case.

- 113. 113 Right to present case and evidence or right for a ‘hearing’ The adjudicatory authority must provide the party a reasonable opportunity to present his case. This can be done either orally or in written. The requirement of natural justice is not met if the party is not given the opportunity to represent in view of the proposed action. In this respect, the most obvious way for individuals to participate in the decision making process is through an oral hearing. An oral hearing provides an affected individual with an important mechanism to put their case effectively and is often a prerequisite for other procedural safeguards, including the right to cross-examination.

- 114. 114 Right to know the evidence against him Every person appears before an administrative authority exercising adjudicatory powers has right to know the evidence to be used against him. The principle of natural justice is so fundamental that it is not to be construed as a mere formality. Where the material relied upon are not enclosed in an order issued for explanation on the incident, misconduct etc, there is no sufficient opportunity.

- 115. 115 Right to challenge the opposing case The fair hearing rule also requires that an affected party be able to challenge the opposition case, including the right to cross-examination witnesses. Denying an accused a fair opportunity of cross- examining as to credit of a witness was a form of ‘procedural impropriety’ sufficiently serious to justify the court coming to the conclusion that there had been a substantial denial of natural justice.

- 116. 116 Legal representation Whether legal representation is permitted depends on the circumstances of each case. The issues to be taken into account include: 1. Seriousness of the sanctions; 2. Difficult points of law exist; 3. The respondents are laymen who will not be able properly to present their own cases; 4. There is no equality of arms; 5. There is a material dispute of facts so that cross- examination is required.

- 117. 117 The duty to provide adequate reasons Reasons help demonstrate that the authority has acted properly and taken into account all relevant considerations. Reasons promote accountability and enhance consistency in decision-making. Where the authority does not give reasons for its decisions, it would prevent the affected party from detecting any faults in the reasoning process that may in turn support a claim for administrative or judicial review. Further, providing reasons is also of benefit to the authority itself in that it serves to concentrate its attention on the relevant issues. If there is a duty to give reasons, it is necessary that they are adequate, intelligible and address the substantial points that have arisen in making the decision.

- 118. 118 Rule Against Bias Bias means an operative prejudice, whether conscious or unconscious, as result of some preconceived opinion or predisposition, in relation to a party or an issue. Dictionary meaning of the term bias suggests anything which tends a person to decide a case other than on the basis of evidence. This principle of natural justice consists of the rule against bias or interest and is based on the following maxims: (1) No man shall be a judge in his own cause. (2) Justice should not only be done, but manifestly and undoubtedly be seen to be done. (3) Judges, like Caesar's wife, should be above suspicion.

- 119. 119 No man shall be a judge in his own cause A discretionary authority cannot decide a case in which he himself is involved, or if he has any personal favour to be done. He has to be impartial and fair in his decision-making. His decision should not be affected by any preconceived views about that matter. Justice should not only be done, but should manifestly and undoubtedly be seen to be done. This is not about the proceedings being visible from a public gallery. It means there must be nothing in the appearance of what happens in a trial that might create an impression that something improper happened.

- 120. 120 Judges, like Caesar's wife, should be above suspicion This maxim comes from a story that Julius Caesar divorced his wife because of rumors of opprobrious behavior. At trial, Caesar said he knew nothing about his wife’s rumored adultery, but asserted that he divorced her because his wife “ought not even be under suspicion”. In a sense, what Caesar was asserting was that he would not allow his wife’s suspected behaviors to sully his status, reputation, and prestige. At the time, Caesar was a powerful and ambitious political player, and he did not want his career thwarted by rumors of his mate’s unreputed behavior.

- 121. 121 There are three types of bias: 1. Pecuniary bias – the administrative authority exercising quasi-judicial function should not have any pecuniary interest in the subject matter of the litigation. Even the lease pecuniary interest in the cause will disqualify the authority from acting as a judge. 2. Personal bias – personal bias may arise by means of friendship, relationship, enmity, personal grudge or professional rivalry. A person who is a relative, friend or enemy of disputing parties is disqualified from acting as a judge. 3. Bias as to subject matter – if the authority that has the power to decide a dispute has some general interest in the subject of the dispute, he is disqualified from acting as a judge. The quasi-judicial authority should not have any interest in the subject matter of the dispute.

- 122. 122 ‘Actual Bias’ and ‘Apparent Bias’ ‘Actual Bias’ A claim of actual bias requires proof that the decision- maker approached the issues with a closed mind or had prejudged the matter and, for reasons of either partiality in favour of a party or some form of prejudice affecting the decision, could not be swayed by the evidence in the case at hand. Actual bias is assessed by reference to conclusions that may be reasonably drawn from evidence about the actual views and behaviour of the decision-maker. A claim of actual bias requires clear and direct evidence that the decision-maker was in fact biased. Actual bias will not be made out by suspicions, possibilities or other such equivocal evidence.

- 123. 123 ‘Actual Bias’ and ‘Apparent Bias’ ‘Apparent Bias’ A claim of apparent bias requires a finding that a fair minded and reasonably well informed observer might conclude that the decision-maker did not approach the issue with an open mind. Apparent bias is assessed objectively, by reference to conclusions that may be reasonably drawn about what an observer might conclude about the possible views and behaviour of the decision-maker. A claim of apparent bias requires considerably less evidence. A court need only be satisfied that a fair minded and informed observer might conclude there was a real possibility that the decision-maker was not impartial.

- 124. 124 Exceptions to the rule against bias 1. Statutory override – statutory provisions may override the rule against bias. However, the courts will not readily find such a statutory override unless this is clear. 2. Necessity – this common law rule principle demands in reality and in all practicality the impossibility to require someone else other than the complained person to hear the matter. Mere administrative inconvenience does not suffice. In other words, the rule against bias will not apply where the impugned decision maker is the only one who can make the decision. 3. Waiver – for waiver to be established there must be (a) knowledge of the bias and (b) the person affected must be aware that they are entitled to make an objection. The objection must be raised as soon as the party is aware of the nature and extent of the bias. They cannot stand by and wait until a final judgment is given.

- 125. 125 Leung Fuk Wah Oil v. Commissioner of Police CACV 2744/2001 Leung was a sergeant of the Hong Kong Police. He was in serious financial difficulties. He was charged with two disciplinary offences, pursuant to section 3(2)(e) of the Police (Discipline) Regulations for failing to be prudent in his financial affairs by incurring unmanageable size of debts whereby his efficiency as a police officer was impaired. A disciplinary hearing took place in early 1999. A Superintendent was appointed as the appropriate Tribunal. Leung was found guilty of the offence on 28 March 1999. The Tribunal then referred the punishment to a Senior Police Officer who imposed a penalty of reduction to the rank of police constable and dismissal from the force.

- 126. 126 The Force Disciplinary Officer confirmed the finding of guilt and penalty. Leung then appealed to the Commissioner of Police. The Deputy Commissioner of Police exercising the delegated authority of the Commissioner dismissed the appeal. Leung applied for judicial review to quash the decisions of the Tribunal, the Senior Police Officer and the Deputy Commissioner of Police on the ground that certain documents considered by the Deputy Commissioner were not disclosed to him. Decision of the Court of Appeal: “Fairness requires the material to be disclosed so that the appellant may have a chance to respond to it.…the judge was right when he considered that the material needed to be disclosed as a matter of fairness…The real question in this appeal is whether the nondisclosure vitiates the decision of the Commissioner and requires it to be quashed.

- 127. 127 …Having considered all the circumstances of this case, it is abundantly clear that the disclosure of the new documents to Mr. Leung would not have made the slightest difference to his petition to the Commissioner… Judicial review is a discretionary remedy. If the breach of the principle of fairness does not produce a substantial prejudice to the applicant, the court is bound to take this into account in deciding whether relief should be given. This is consistent with the concept that the court should not substitute its own decision for that of the decision- maker.”

- 128. 128 Lau Tak-pui v. Immigration Tribunal [1992] 1 HKLR 374 The Immigration Tribunal established under the Immigration Ordinance in exercising its power under section 53D of the Ordinance determined that Lau had not been born in Hong Kong, that the removal order made by the Deputy Director of Immigration was therefore valid and that his appeal against such orders should be dismissed. There is no express provision requiring the Tribunal to give reason. The Tribunal did make a statement explaining the ground for its decision as follows: “After careful consideration of the evidence given by all parties concerned and by the witnesses presented, the Tribunal has come to the conclusion that the Appellants, have not discharged the burden of proof that they were born in Hong Kong and therefore do not enjoy the right of abode in Hong Kong under section 2A of the Immigration Ordinance. The appeal is dismissed.”

- 129. 129 The issues to be considered: • Should the principles of natural justice be applicable in this case? • Was there a duty to give reason? • Was that reason an adequate one? Decision of the Court of Appeal: “Hong Kong Immigration Tribunal was and is a fully judicial and non-domestic body when hearing such appeals … it exercises powers affecting the liberty and residential and citizenship rights of appellants pursuant to statutory provisions of some complexity. These are special circumstances which…require as a matter of fairness the provision of outline reasons showing to what issues the Tribunal has directed its mind and the evidence upon which it has based its conclusions.

- 130. 130 Turning then to the adequacy of the reasons given in the respective appeals they show that the only issue …fell for their determination, namely the appellant’s places of birth, had been addressed and, by necessary implication, that all the evidence germane to that issue had been considered. The conclusion that the applicants had not been born in Hong Kong was the basis of fact upon which the Tribunal determined that they did not enjoy a right of abode in the Colony. The requirements, being a statement of the grounds for the findings, and of natural justice, being at least as stringent as any which may derive from the terms of s 53D, were met. It is not suggested that either determination was aberrant on its face.

- 131. 131 Mohamed Yaqub Khan v. Attorney General [1986] HKLR 922 Khan, a Superintendent of the Hong Kong Auxiliary Police Force, was dismissed by the Commissioner of Police on the ground of his misconduct. Khan was not informed of the actual allegations against him. • Should the principles of natural justice be applicable in this case. The Court: “…in cases where an officer can only be dismissed for cause…the requirements of natural justice will depend upon the reason which in fact underlies his dismissal. At the very least, we would think he is entitled to know the reason for his dismissal. …we have come to the conclusion …to dismiss Mr. Khan were matters of misconduct…we therefore conclude that in the circumstances Mr. Khan ought to have been informed of the contents of that memorandum and given the opportunity to make representations in answer.”

- 132. 132 Wong Pun Cheuk v. Medical Council [1964] HKLR 477 The Director of Medical and Health Services referred a case against Wong, a medical practitioner, for prescribing drugs not required for the purpose of medical treatment to the Medical Council. The Medical Council of Hong Kong decided to withdraw the authorization to prescribe drugs from Wong after an inquiry. The Director of Medical and Health Services chaired the Medical Council in this inquiry. The issue to be considered by the Court: is there any Bias?

- 133. 133 Decision of the Court: “…it is clear that the Director....is in the position of a complainant or accuser, having presumably previously gone into the evidence available in order to form the relevant opinion, and being of the relevant opinion refers the case for decision to the Medical Council. At the hearing of the inquiry the decision on the case as to whether or not to make the relevant recommendation is made by the Medical Council, and therefore the members of the Council are the judges of the case, and have to adjudge whether or not the recommendation should be made. It is also clear that the Director is not only a member of the Medical Council but he is also its chairman…. This seems to me to be contrary to the legal principle that a person should not be a judge in his own cause, ... and it therefore appears to me to be unjust.”

- 134. 134 Lam Sze Ming and Another v. Commissioner of Police CACV 912/2000 Lam, Au and Lai, were police officers. They were arrested together with Cheung and Kong in an police action against illegal gambling. Lam was charged with gambling in a gambling establishment. No evidence was offered against Au and Lai for they were willing to give evidence as persecution witnesses against Cheung and Kong who were charged with more serious gambling related offences. Lam was acquitted and Cheung and Kong were convicted. Lam was then charged in the police disciplinary proceedings that he had committed conduct calculated to bring the Public Service into disrepute. The conduct complained of was that he frequented the premises for the purpose of unlawful gambling.

- 135. 135 For the purpose of the disciplinary proceedings, Lam was provided with the charge sheet; a list of witnesses, a list of exhibits, statements made by Au and Lai to the police during interrogation and a bundle of photographs. However, the following documents were not provided: (i) statements made by Au and Lai under caution at the time of their arrest; (ii) the transcript of court proceedings; (iii) an immunity document and all negotiation relating to negotiations between the prosecution and Au and Lai were not released to Lam. Lam was found guilty and was dismissed. Lam applied for judicial review against the decision. The issue to be considered by the Court: must these documents be disclosed?

- 136. 136 Decision of the Court of Appeal: “The test to be applied in determining whether disclosure should be made…material… (1) to be relevant or possibly relevant to an issue in a case; (2) to raise or possibly raise a new issue, whose existence is not apparent from the evidence the prosecution proposes to use; (3) to hold out a real (as opposed to fanciful) prospect of providing a lead on evidence which goes to (1) or (2). The primary duty is to disclose the material which has been gathered by the prosecution in the course of its investigation. It does not follow that only such material need be disclosed. There may be other material.”

- 137. 137 …applying the primary duty principle to the documents not disclosed in this case, I am satisfied, firstly, in relation to (ii) to (iii), that…failure to disclose does not amount to a breach of natural justice resulting in an unfair trial.… The District Court transcript was made available in the sense that the applicants were fully aware of its existence and were advised as to how they could acquire a copy. The immunity documents concerned only the District Court proceedings. The terms of the witnesses’ immunity in giving evidence against four other defendants in different proceedings could not, in my judgment, be of such relevance to the disciplinary proceedings to the extent that a failure to disclose them would or might result in justice not being done.

- 138. 138 …in relation to (i) above, I am…satisfied that nondisclosure does not amount to a breach of natural justice for the purpose of these proceedings… the applicants’ complaint amounts to a failure by the Prosecutor to seek out and collect material which did not form part of her case. This was not her duty. It cannot be said, in this case, that her failure to do something which she was under no duty to do, amounts to unfair conduct or a breach of natural justice.

- 139. 139 Lam Siu Po v. Commissioner of Police FACV No. 9 of 2008 A police constable, Lam, engaged in stock market dealings. He lost heavily, found himself deeply in debt, petitioned for his own bankruptcy and was adjudicated bankrupt in September 2000. Consequently he was charged in December that year with a disciplinary offence. There were two disciplinary hearings. The first hearing ended in Lam being convicted on 2 March 2001. But that conviction was set aside by the Force Discipline Officer for procedural irregularity. The police officer who had represented the appellant at the first hearing was not available at the second hearing, which commenced on 14 December 2001.

- 140. 140 That police officer was replaced by Lam’s another representative. But Lam lost confidence in that replacement. And after being told that he could not engage a legal practitioner to defend him, the appellant appeared in person at the second hearing. Regulation 9(11) and (12) of the Police (Discipline) Regulations provided that: “(11) A defaulter may be represented by –(a) an inspector or other junior police officer of his choice; or (b) any other police officer of his choice who is qualified as a barrister or solicitor, who may conduct the defence on his behalf. (12) Subject to paragraph (11), no barrister or solicitor may appear on behalf of the defaulter.“ On 27 March 2002 Lam was again convicted. The penalty imposed on him was compulsory retirement with deferred benefits. Whether the absolute bar to legal representation is constitutional?

- 141. 141 Article 10 of Bill of Rights Ordinance provides that: “All persons shall be equal before the courts and tribunals. In the determination of any criminal charge against him, or of his rights and obligations in a suit at law, everyone shall be entitled to a fair and public hearing by a competent, independent and impartial tribunal established by law.” The Court of Final Appeal: Article 10 protections come into play…when a person is subject to “a determination of his rights and obligations in a suit at law”. When it is engaged, it enables the individual faced with a determination by a governmental or public authority which may affect his civil rights and obligations to say: “I am entitled to the protections of Article 10, including the right to a fair and public hearing by a competent, independent and impartial tribunal established by law”.

- 142. 142 In my view, Article 10 is clearly engaged in relation to the disciplinary proceedings in present case. The Administrative Instructions…make it clear that punishment for the disciplinary…which the appellant was charged is “normally terminatory”. Such was in fact the nature of the punishment meted out in this case. Where Article 10 is engaged, the person concerned becomes entitled to “a fair and public hearing by a competent, independent and impartial tribunal established by law”. Regulations 9(11) and 9(12) are therefore systemically incompatible with Article 10. Pursuant to section 6(1) of the Bill of Rights Ordinance, the Court is empowered to make such order in respect of this violation of the Bill of Rights as it considers appropriate and just in the circumstances.

- 143. 143 The Court concludes that: (a) Article 10 is engaged in respect of the appellant’s disciplinary proceedings. (b) The requirement of a fair hearing means that the disciplinary tribunal ought to have considered permitting the appellant to be legally represented. (c) Regulations 9(11) and 9(12) are inconsistent with Article 10 and must be declared unconstitutional, null and void. (d) Since the tribunal failed to consider and, if appropriate, to permit legal representation for the appellant, he was deprived of a fair hearing in accordance with Article 10 so that the disciplinary proceedings were unlawful and the resulting convictions and sentences must be quashed.