This volume of the Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission's report focuses on major violations of bodily integrity rights committed during the Commission's mandate period. It examines unlawful killings, enforced disappearances, detention, torture, and sexual violence. While most of these violations traditionally require state action, the Commission took an expansive view to include non-state actors, given that many victims are concerned with addressing the harms suffered rather than the official status of perpetrators. The volume provides a historical overview of security agencies in Kenya and analyzes specific violations including massacres during the Shifta War and conflicts in Mt. Elgon and Tana River, as well as political assassinations and abuse in detention under successive Kenyan governments from colonial

![33

CHAPTER

TWO

History of Security Agencies:

Focus on Colonial Roots of the

Police and Military Forces

The soldiers killed our men and raped our girls but there was no one to

complain to. When you complained […] they told us that the soldiers

are the law themselves and if they kill you, you have no one to talk to.1

While he was doing that, crying on top of the roof, the neighbours heard

a bullet shot. That gun shot hit my son in the left leg, disabling him and

he fell from the roof. But he was still pleading with the police saying:

“Please, do not kill me.” Instead, the police went ahead and shot him

right in the pelvis. By that time, the police vehicle had also arrived and

they carried the young man to the hospital while he was still speaking. I

am told he was still asking them; “why have you killed me?’’ When they

reached the hospital, he was pronounced dead.2

Introduction

1. As institutions, the police and the military forces are at the centre of Kenya’s

history of gross violations of human rights. Across the country, the Commission

heard horror accounts of atrocities committed against innocent citizens by the

police and the military. The history of security operations conducted by these

1 TJRC/Hansard/Women’s Hearing/Mandera/26 April 2011/p.4.

2 TJRC/Hansard/Public Hearing/Busia/1 July 2011/p. 29.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/volume2a-130522040202-phpapp01/85/Volume-2-a-47-320.jpg)

![35

Volume IIA Chapter TWO

REPORT OF THE TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION

4. The Commission benefitted from a number of attempts over the past decade to

shed light on the inner workings of the police. Because of the emptiness of the

field, these attempts have had to start with very basic definitions. The most basic

of these definitions explains who the police are in an African context:

National police forces are the formal conduit through which regime power or authority

is normally channelled. The rationale of the police remains maintaining the order that

the regime sustaining them defines as appropriate.4

5. Additional definitions have sketched out the primary functions of African policing

as‘the maintenance of law and order, paramilitary operations, regulatory activities

and regime representation.’5

Finally, some scholars believe that African experiences

also require an preliminary understanding of a‘police system’. This is a much more

nebulous concept that attempts to explain the overall meshing together of key

individuals and personalities with more formal policing structures and functions:

The police sector…forms a system [defined] as an organization made up of groups and

individuals existing for a specific purpose, employing systems of relatively structured

activity with a structured boundary and driven by actors pursuing their own goals

according to their own incentives and calculations. The complexity of the police sector

results from the interactions between the various parts of the system.6

6. While these three definitions offer much needed simplicity and clarity, the

Commission remains acutely aware that the overall story of policing in Africa

is deeply rooted in some of the most complex and contested issues in the

continent’s history. For instance, the question of law and order in colonial period

presents a number of fundamental difficulties. It is clear that the arrival of the

British signalled the entrance of an entirely new legal system based on the

situation pertaining in England at the time. Initially, no provisions were made

whatsoever for pre-existing African notions of law, order, crime and punishment.

New authorities, new judicial personnel and new personnel in charged

populating this new English-based system of law and order. These included

judges, magistrates, administrative officers, clerks, messengers and, of course,

policemen. More often than not, all these people were drawn from Britain and

other parts of Commonwealth. In essence, the British introduced an entirely alien

legal system manned almost exclusively by either the British themselves or their

emissaries.

4 Alice Hill, Policing Africa: Internal Security and the Limits of Liberalization, 6.

5 Alice Hill, Policing Africa: Internal Security and the Limits of Liberalization, 8.

6 Alice Hill, Policing Africa and Internal Security and the Limits of Liberalization, 11.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/volume2a-130522040202-phpapp01/85/Volume-2-a-49-320.jpg)

![46

Volume IIA Chapter TWO

REPORT OF THE TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION

line in the middle of 1900. When construction ended, the Uganda Railway police

continued to provide protection along these lines.

35. By 1902, the railway police force consisted of some four hundred men commanded

by a dedicated superintendant (G. Farquhar) and an assistant (C. Ryall). Two further

European inspectors were also appointed as well as a number of Indian Deputy

Inspectors. The Railway Police worked independently of the British East Africa

Police. But it is not at all clear from the sources whether they developed their own

operational codes and procedures.

36. The creation of administrative posts along the line led to the second branch of

policing. The Collectors and Assistant Collectors sent to places like Voi, Makindu,

Sultan Hamud and further up the railway required the services of police more

concerned with broader law and order issues that—for the most part—had very

little to do with the railway itself. These new administrative centres represented

the sharp end of the colonial project; the point at which the British introduced

(imposed) new ideas of right and wrong on a bewildered population. The police

were amongst the first purveyors of the reality that traditional African norms no

longer applied. More literally, the police acted as the eyes and ears for the often

oblivious Collectors and Assistant Collectors. They conducted patrols and carried

out surveillance again for any threats to the nascent new order. Officers were often

recruited locally by the respective Collectors. No central body oversaw this process.

37. The result was nothing short of chaotic. Each district essentially had its own

autonomous force. Precious little united them. From one district to the next,

uniforms changed as did formations, pay and chains of command. The only

commondominatorwasanunhappyone:thelackofprofessionalismandresources.

A Captain Ewart travelling inland from Mombasa to Kiambu in 1904 described all

the units he encountered along the way as ‘an extraordinarily ragged lot, almost

untrained and [with] little in the way uniforms.’There was also no consistency to the

equipment used by the various forces. In general, however, the guns and weapons

supplied to the police were of very poor quality having already either been used or

rejected by the King’s African Rifles. Indeed, early there was even one extraordinary

instance when guns dumped in the sea because they had outlived their usefulness

were recovered, cleaned and re-issued to the various police units.

38. The situation persisted until 1904 when a Captain McCaskill, Ewart’s successor,

presented the Foreign Office with a series of proposals and estimates for the long

overdue amalgamation of the various forces into one centrally organized structure.

The proposals were studied and eventually approved by both the Foreign Office](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/volume2a-130522040202-phpapp01/85/Volume-2-a-60-320.jpg)

![60

Volume IIA Chapter TWO

REPORT OF THE TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION

calibre of [European] officers necessary to properly run such departments. The

following year Captain Edwards—the new Inspector General of Police—offered a

completely different opinion. He was of the view that criminal investigation and

criminal records units were hallmarks of a modern police force. He recommended

that notwithstanding the lack of personnel, the force had to consider creating

them. Edwards was particularly anxious about criminal records describing them

as weapon for detection and against re-offending. However, no movement

was made on the issue. For the next decade, the closest that the force came to

criminal records was a small Finger Print unit run by a single officer.

75. The question of a Criminal Investigation Department returned in 1925 when the

Police Commissioner bemoaned the lack of funds and personnel necessary to

handle serious cases. Even so, the decision was made to push ahead with the formal

creation of a specialized unit. It is unclear how this decision came about. One thing

is certain, Nairobi and other settled areas at this stage played host to an expanded

array of crimes—forgery, rape, murders, housebreakings, violent robberies—that

resulted in the usual hue and cry that something needed to be done. The more

sensational cases were reported in the press in lurid detail further creating the

impression that crime was spiralling out of control. More likely than not, the new CID

was a product of the need (and the need to be seen) to respond to the activities of

an increasingly sophisticated criminal class. Few other details about the early history

of the department are available other than attempts were made to recruit the most

qualified African, Asian and European officers.The following year—1926—was spent

giving organisational shape to the department. The Criminal Record Department

was also formalized.

76. While it got off to a slow start, by the mid-1930s the CID began to be regarded

as something of a success story. The department was credited with developing

a network of informants that finally allowed the police to arrive at some sort of

understanding of the crime and criminals that so plagued the colony. By the

very nature of their work, these agents and informers worked in the shadows

and in anonymity. Very little is known about their identities and their motives

for engaging in such work. Some may well have been criminals themselves or at

the very least, associates. Whatever their identities and their motives informants

helped the police to amass criminal intelligence, make arrests and initiate

prosecution. Statistically, the Police Department began to register impressive

increases in three key areas: the number of cases being reported, conviction rates

and the number of parolees under police supervision. At their simplest, increases

between 70 percent and 80 percent provide evidence of increased efficiency and

productivity in a buffed-up police force. These figures do, however, have to be](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/volume2a-130522040202-phpapp01/85/Volume-2-a-74-320.jpg)

![77

Volume IIA Chapter TWO

REPORT OF THE TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION

led by a Colonel Colvile. What followed were two years of fierce fighting and the

eventual subjugation of Bunyoro resistance five years later.

119. One other aspect of the Ugandan Rifles’ early campaigns deserves mentioning:

weaponry. The regiment provides the clearest examples bestowed by superior

weaponry. As Lugard left Mombasa, he took with him a single Maxim gun.

Described in the literature as‘worn-out’, the Maxim gun nevertheless underscored

that the key difference between the colonial and traditional militaries was the

ability to access modern firearms.17

And in the early 1890s, there was no weapon

more advanced than the Maxim. The gun itself was a re-worked version of the

heavier and more cumbersome Gatling gun and was capable of firing 600 rounds

per minute. A Maxim prototype had been used during the Emin Pasha expedition.

Somehow—it is not clear how—Lugard came to possess the final version of the

gun or why it was in such poor condition. At any rate, the gun had a brief but

starring role in Lugard’s campaign. During the battle of Mengo in January 1892,

the gun was fired for the first time leaving observers and the enemy with no

doubts about the weapon’s power. Weapons such as the Maxim gun were what

gave colonial formations the edge over their enemies. Without such weapons, it is

debatable whether they would have been able to take on African armies that were

often much better organized and disciplined.

Uganda Rifles and the Nandi Expeditions

120. Kenya’s military history is deeply intertwined with Uganda’s not least because until

1902, all land west of Lake Naivasha was actually part of the Uganda Protectorate.

Developments in [modern-day] Uganda had a direct impact on events in [modern-

day] Kenya. And so it was that was that as the unrest was quelled in Uganda,

attention turned to Kenya which presented similar challenges to British authority.

The Commission has already noted the difficulties that the Company along the

coast in Tana and Jubaland. These troubles followed the British as they moved

further inland with the railway and its attendant administration. As the railway

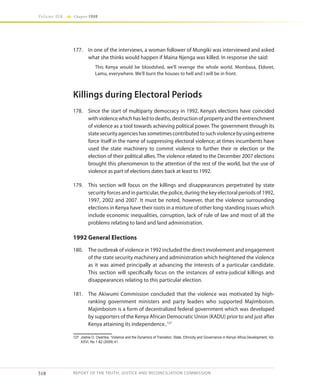

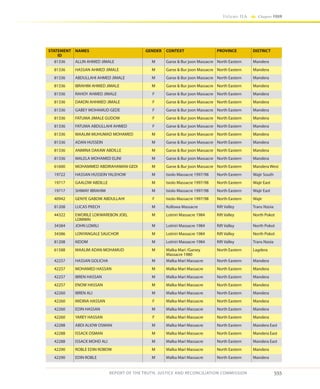

reached the western edge of the Rift Valley, it ran into very serious trouble with

local inhabitants completely opposed to the British passage and presence in their

lands. Nandi campaigns against the British are a much studied topic in Kenya’s

early colonial history on account of their determined nature.18

For the Commission,

they provide yet further evidence of a military past defined by spectacular and

unequal violence unleashed in the name of colonial pacification.

121. The Uganda Rifles were central to British efforts to take on the Nandi. The regiment

was, by some distance, the best trained and equipped in the region. It was also much

17 Lieutenant-Colonel Moyse-Bartlett, The King’s African Rifles: A Study in the Military History of East and Central Africa, 1890 – 194, 49.

18 For detailed narrative on Nandi resistance see, A. T. Matson, Nandi Resistance to British Rule 1890 – 1906, Nairobi: East African

Publishing House, 1972.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/volume2a-130522040202-phpapp01/85/Volume-2-a-91-320.jpg)

![87

Volume IIA Chapter TWO

REPORT OF THE TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION

Orkoiyot’s intervention was even more direct.37

His divination was used to determine

the timing of raids. He was also was consulted on questions of the conduct and

organisation of raids.

148. It was the Orkoiyot’s militaristic role that led successive British administrators to

conclude that Koitalel was in fact the leader and the person behind the decade

long Nandi resistance. Once again while British readings of the situation were not

entirely incorrect, they are not nuanced enough. Koitalel was almost certainly

centrally involved in the planning of what was a focused, long-running and

determined campaign. Even so, it is important to appreciate that Orkoiyots were

not commanders in the classic [Western] sense and did not have executive powers.

Indeed their decisions—even ritual ones—could be challenged. Furthermore,

Nandi society was also highly militarized with entire age sets dedicated to the

commission of war. They were somewhat self-running with the power to hold

discussions and make decisions within themselves. They did not necessarily

require the hands-on involvement of the Orkoiyot. The British presence in Nandi

country presented a unique and unprecedented problem that demanded a unique

and unprecedented response from Koitalel. In becoming the face and the focal

point of the resistance, he re-defined the Orkoiyot’s mission for the exigencies of

colonialism.

Ket Parak Hill, 19 October 1905

149. Meinertzhagen’s disdain for Koitalel was profound, almost personal. His diary it

makes clear that the only solution to the Nandi problem lay in either capturing or

killing Koitalel:

Koitalel is a wicked old man and at the root of all our trouble. He is a dictator, and as such

must show successes in order to retain power. He is therefore in favour of fighting the

British. Many of his hot-heads support him. My main reason for trying to kill or capture the

laibon is that, if I remove him, this expedition will not be necessary and the Nandi will be

spared all the horrors of military operations. But both the civil and military authorities are

intent on a punitive expedition.The military are keen to gain a new glory and a medal and

the civil people want the Nandi country for the new proposal of the White Highlands—

just brigandage.38

150. That Meinertzhagen intended to eliminate or kill Koitalel was also evident. In a series

of events that are still very murky, Meinertzhagen managed to arrange a meeting

with Koitalel for the 19th

of October 1905 in location known locally as Ket Parak Hill.

The ostensible purpose of the meeting was to discuss a truce of sorts. Two things

37 Details can be found in T. Matson, “Nandi Traditions on Raiding”, Hadith 2 (1970), pp. 61 – 78.

38 Richard Meinertzhagen, The Kenya Diary 1902 – 1906, 223](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/volume2a-130522040202-phpapp01/85/Volume-2-a-101-320.jpg)

![96

Volume IIA Chapter TWO

REPORT OF THE TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION

documents—the ‘Hanslope Park files’—speaks at the very least to a reluctance to

allow proper scrutiny of the Army’s role in the quashing of Mau Mau.59

170. The Commission’s study of Kenya’s colonial history has turned up a number of trends,

patterns and practices that have endured post-colonially. The military’s assessment

of its role in screening and interrogating Mau Mau suspects provides a particularly

striking continuity. The Kenya Army retained the procedure whereby the function of

the army in security operations [involving civilians] was establishing and maintaining

a cordon. The procedure emerged most spectacularly in February 1984 during a

security operation at the Wagalla Airstrip in Wajir. The same insistence on military

distance from the main action also prevailed in official descriptions of Wagalla

unmasking the army as one of the most fixed and unchanging institutions in Kenya.

Lanet 1964: Mutiny in the Ranks

171. As the Emergency wound down and it became evident that Mau Mau would

be defeated, the military embarked on the familiar routine of demobilizing

and discharging the hundreds of extra troops raised during the Emergency.

Independence from Britain was fast approaching. De-colonizing the KAR and

handing it over to local [African] administrators and commanders rose to the very

top of the military agenda. It became a difficult issue to address because the army

overseers—like the police ones—had done nothing to engender the development

of a class of African professionals. Basic primary education for recruits was a feature

of the KAR from the 1950s but none of the African enrollees ever progressed into

post secondary education. While promoting Africans was a priority, there were

in effect no Africans to promote to leadership positions. And so it was that in

December 1963--Independence—more than fifty percent of the all senior and non-

commissioned officers were still non-Africans.60

172. Another obstacle was the lack of ethnic diversity. The British had diligently divided

indigenousAfricancommunitiesintothemartialandnon-martial. Theso-calledmartial

races were regarded as inherently suited to military service. The result was an army

largely populated by a handful of ethnic groups. A 1959 report on the KAR revealed

that 77% of all recruits were drawn from the Kamba, Kalenjin, Samburu and other

communities that had for so long been characterized as martial.61

For an institution

meant to symbolize Kenya’s newfound nationhood and nationalism, the KAR stood

out as a sore reminder of division and colonial stereotypes. Despite all these problems

(and others besides), the KAR was Kenya’s premier military formation; there was no

alternative. Upon Independence on the 12th

of December 1963, the KAR became the

59 For more on the Hanslope Park files, see DavidAnderson, “Mau Mau in the High Court and the “lost” British EmpireArchives: Colonial

Conspiracy or Bureaucratic Bungle?” Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 39 5 (2011), pp. 699 – 716.

60 Timothy Parsons, “The Lanet Incident, 2 – 25 January 1964: Military Unrest and National Amnesia in Kenya” The International

Journal of African Studies 40 1 (2007), p. 61.

61 From Timothy Parsons, “The Lanet Incident, 2 – 25 January 1964: Military Unrest and National Amnesia in Kenya” The International

Journal of African Studies 40 1 (2007), p. 60.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/volume2a-130522040202-phpapp01/85/Volume-2-a-110-320.jpg)

![106

Volume IIA Chapter THREE

REPORT OF THE TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION

18. By the late 1950s, the Somali Youth League was most certainly in decline. Its place

at the helm of Somali nationalism in Kenya had been taken over by the Northern

Province People’s Progressive Party. The NPPPP, as it was popularly known, forms

the final link in the chain of events leading up to the Shifta War. As with most other

currents in the history of Northern Kenya, the impulses that inspired the formation

of the NPPPP originated in Somalia proper. In 1960, officials in British Somaliland

sprung something of a surprise. They suddenly declared British Somaliland, the

predecessor of modern-day Somaliland, independent. A few days later, British

Somaliland was united with the Trust Territory of Somalia (formerly Italian

Somaliland) to form the Somali Republic. Administrators in Kenya, Djibouti and

Ethiopia were caught off guard because they had received no notice about a move

that would effectively revive the Bevin Plan.

19. An article in the Somali independence constitution articulated the imperative

of achieving “the union of Somali territories by legal and peaceful means”.4

The

new state of Somalia adopted a flag in the centre of which was a five-pointed star

symbolizing the union of five areas: Italian Somaliland, British Somaliland, French

Somaliland (Djibouti), Ethiopia’s Ogaden Province and Kenya’s Northern Frontier

District.

20. In a speech to the United Nations, Ali Sharmake, the president of Somalia, went

even further and declared that “[our] neighbours are Somali kinsmen whose

citizenship has been falsified by indiscriminate boundary arrangements, so how

we can regard our own brothers as foreigners?”5

These pronouncements from

the newly-independent state of Somalia revived long dormant aspirations in

Northern Kenya. Within months, the NPPPP was up and running. Headquartered

in Wajir, the party was led by Wako Happi and Maalim Stanboul. Happi and

Stanboul made it clear that their primary objective was secession from Kenya.

Their message was wildly popular and the party quickly attracted Somali and

non-Somali members from throughout the region. Somali populations in Nairobi

were drawn into the cause by an NPPPP affiliate organisation known as the

National Political Movement.

21. How a small, isolated and rural party came to present such a fundamental challenge

to Kenya’s territorial integrity has as much to do with its fortuitous timing as

anything else. The NPPPP came to prominence precisely when outgoing British

4 Ahmed Issack Hassan, North Eastern Province and the Constitutional Review Process: Lessons from History http://www.braissac.

com/northeastern_constitution_review_proocess.html Accessed 9th January 2012.

5 Ahmed Issack Hassan, North Eastern Province and the Constitutional Review Process: Lessons from History http://www.braissac.

com/northeastern_constitution_review_proocess.html Accessed 9th January 2012](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/volume2a-130522040202-phpapp01/85/Volume-2-a-120-320.jpg)

![120

Volume IIA Chapter THREE

REPORT OF THE TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION

63. General accounts indicate that dysentery, pneumonia and malaria frequently

swept through the camps. Epidemics of highly contagious, tuberculosis presented

particular problems and quarantine areas (“tuberculosis manhattans”) were

created in the compounds. Starvation was a serious problem. The only food on

offer in the camps was ugali; the stiff maize-based porridge that many Northerners

found unpalatable and unfamiliar. As Hassan Liban plaintively explained it, “they

gave us ugali and we could not eat it.”31

64. For security reasons, livestock were only allowed to use thin belts of pasture

surroundingthecamps.Asaresult,milkandmeatyieldsplummeted,deprivingthose

in the camps of much needed nutritional variety. Nearly all villages had makeshift

graveyards where the bodies of the dead were unceremoniously deposited.

65. As the camps were gradually shut down towards the end of 1967, people were

released to return to their homes. For Garbatulla elders, this long-awaited moment

of freedom marked the beginning of an even more difficult period during which

the full impact of Daaba began to be felt.32

After so many months confined in the

villages, these former inmates could not really say where“home”was. Unlike Central

Kenya, where detainees were systematically released back to their villages and

communities, the nomadic peoples of Isiolo (and elsewhere in the north) found

themselves stranded. They had been displaced. A slow but inexorable drift towards

the towns began to take place. Uncertainty about where to go and what to do forced

many people into urban centres such as Isiolo. The elders’ depiction of town life is

bleak. People started to live unstructured lives characterised by urban poverty,

substance abuse and trauma:

[They] could only find employment as watchmen or night guards or prostitutes. Many

started chewing miraa (khat) as a way of obliterating memories…for some, life was

never the same again…many people complained of pain, headache, depressed mood

and of death and dying.33

66. Disbandment of the camps did not, therefore, mean a return to the predictability

of pre-village life; an irreversible chain reaction had been set off that nobody could

control.

67. TheideaofDaabaasatotalandunwelcomerupturebetweenthepastandthepresent

was brought up again in subsequent discussions about what the elders describe as

forced conversion to Christianity. The complete failure of the government to provide

any services to the people it released from the camps provided an opportunity for

31 TJRC/ Hansard/ Public Hearing/ 26 April 2011/ Mandera/ p.9

32 Dying an Invisible Death and Living an Invisible Life: A Memorandum by Garbatulla Elders, February 2011. TJRC/ISL/1.

33 Dying an Invisible Death and Living an Invisible Life: A Memorandum by Garbatulla Elders, February 2011. TJRC/ISL/1.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/volume2a-130522040202-phpapp01/85/Volume-2-a-134-320.jpg)

![184

Volume IIA Chapter FOUR

REPORT OF THE TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION

119. With thousands of elephants and rhinos killed, conservationists began to

speak openly about the complete disappearance of these animals from Kenya’s

ecosystems.51

Anxieties surrounded the continued viability of Kenya’s vital tourist

industry. The export of violent poaching to other parts of the country triggered

an outcry. With one outrageous attack after another on animals, tourists and

game rangers, public anger at government inaction reached a fever pitch. Mr.

Kholkholle, the member of parliament for Marsabit South, spoke for many Kenyans

when he questioned the ineffective response from the Ministry of Wildlife and the

government as a whole:

I am very surprised for the Assistant Minister to say that these poachers have automatic

weapons and, therefore, probably his ministry is unable to deal with these people. If the

government has dealt with Shifta, who were many in numbers and also very powerful,

why not these few poachers?52

120. In early 1975, then Vice President Daniel arap Moi declared that “no effort will be

spared to stamp [poaching] out”.53

Three years later, President Kenyatta banned all

forms of hunting.

121. The second branch of Shifta violence to elicit a reaction from the government

was violence aimed directly at government employees, property, installations

and the like. Like poaching, such attacks were depicted as intolerable. During

the war, strikes against the government were, of course, deliberate. The post-

war situation was much more opportunistic. Government convoys, for instance,

were a favourite target. If the raiders were lucky, the cars might be carrying civil

servants’ salaries. So it was in 1989 in Hulugho, a tiny Garissa town, when three

policemen were killed while transporting the payroll. While not unusual, such

incidents had the capacity to both shock and anger the administration. And

as Hulugho again shows, fairly determined attempts were made to track down

bandits involved in such incidents.

External threat

122. Anotherelementofthesecurityequationinpost-ShiftaNorthernKenyawasexternal.

Long, porous borders and shared ethnic identities have long meant that the region’s

connections to Somalia and southern Ethiopia go far beyond the superficial. Indeed,

deeply held beliefs about Somali identity and the Somali nation were at the core of

the war. The end of the war put an end to Somalia’s territorial ambitions in Kenya. It

51 See for instance, David Western ‘Patterns of Depletion in a Kenya Rhino Population and the Conservation Implications’ (1982) 24

Biological Conservation 147

52 Kenya National Assembly Official Record (Hansard) 14th

June 1972, 75

53 Quoted in John Tinker, ‘Who’s killing Kenya’s jumbos?’(1975) 22 New Scientist 452](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/volume2a-130522040202-phpapp01/85/Volume-2-a-198-320.jpg)

![200

Volume IIA Chapter FOUR

REPORT OF THE TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION

and movements of the raiders. By noon on 10 November 1980, it became evident

that a number of women and children had been caught up in the dragnet. A

number of civil servants, including Rabasi, found themselves at the field as well.

Government employees, women and children were released soon after Kaaria and

his team arrived to tour the grounds. The rest were to remain there as questioning

continued. Special Branch officers and the police were seen to be at the forefront of

the actual questioning and handling of civilians. There was also a military presence

of some kind. Rabasi recalls seeing a number of military men dotted through the

field. They were heavily-armed but had no direct interactions with the gathered

men. Their“mean-looking faces”were a source of great concern not least to Rabasi

himself. He also spotted four military personnel carriers strategically parked at the

corners of the field.

170. After his tour of the field on 10November 1980 Kaaria issued yet another statement

that was reported in the newspapers of 11 November 1980.100

There was no sign

of any softening of the government position. If anything, Kaaria intensified the

crackdown, with the disbandment of the provincial, district and location committees

that were so central to administration. He reiterated that the government would not

tolerate any form of what he referred to as “terrorism and banditry”. The screening

continued with scores of men all individually subjected to a barrage of questions

about the said terrorism and banditry. Even as conditions deteriorated due to the

lack of water and food, the men would remain detained at the field until the exercise

wound down over the next couple of days.

Main state actors

171. As discussed earlier, security operations require permissions and authorisations.

These permissions are key determinants of how, when, and by whom an operation

is to be carried out. What Bulla Karatasi quite clearly demonstrated was that these

permissions and authorisations were generated at the District and Provincial

Security Committee level in Garissa itself. Kaaria’s testimony was unequivocal on this

particular issue: the decision to conduct the rounding up, holding and screening

operation came out of a joint District and Provincial Security Committee meeting

held less than an hour after the shooting in the bar. No go-ahead or green light was

needed or sought from Nairobi or from anywhere else. All approvals required to

launch the operation were local. In this sense, Bulla Karatasi provided a text book

example of an operation executed in accordance with the guidelines set out in

the province’s Internal Security Scheme or, as Kaaria sometimes referred to it, the

[Security] Charter. As described above, the charter identifies both the Provincial

100 Thousands Rounded Up’ The Standard 11th

November 2011 1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/volume2a-130522040202-phpapp01/85/Volume-2-a-214-320.jpg)

![221

Volume IIA Chapter FOUR

REPORT OF THE TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION

Wagalla Massacre

During that short period that we stood there, what I saw and what has remained very

distinctly in mind today is a pile of bodies to my right and two naked people carrying yet

another body to put on the pile.139

233. By far, the‘Wagalla Massacre’of February 1984 is the most spoken about massacre

in Kenya and represents a tragic story of how a government can turn against and

massacre its own citizens. According to one victim of the excesses of the security

operation, ‘[t]he government that should protect us ate us like a hyena eats a

goat’.140

The Commission conducted its hearings in Wajir on three separate days

in April 2011. Commissioners also had an opportunity to visit Wagalla Airstrip, the

site of the Wagalla Massacre. At the site, survivors demonstrated how they were

treated during their detention at the airstrip in February 1984.

Background

234. The Wagalla Massacre must be understood in the broader context of clan relations

in Wajir, and North Eastern Province in general, and the politicisation of these

relations.

Clan relations in Wajir

235. Wajir District is dominated by three main clans - the Ajuran, the Degodia and the

Ogaden. The Garre and Murulle are also present in Wajir, but in smaller numbers.

Clan issues among the Somali are complex and have been the focus of much

historical and anthropological attention as scholars have sought to understand

how a people united by ethnicity and religion have fallen out so spectacularly over

clan identity.141

Somali clans are best described as the largest possible grouping of

families, sub-clans and lineages who claim a common ancestry.

236. There are six distinct Somali clans: the Darood, Isaaq, Hawiye, Dir, Digil and

Rahanwayn. While the Ajuran and the Degodia are generally understood and

referred to as separate clans, they are in fact sub-clans of the larger Hawiye clan.The

Ogaden are a sub-group of the Darood. Sub-clans are further divided by a caste-

like system that determines such issues as marriage and access to land and political

power. In a further complication, clan identities are neither fixed nor immutable.

Dominant clans have a long tradition of absorbing weaker and more subservient

ones. Entire clans can and have been known to define and redefine themselves

139 TJRC/Hansard/Public Hearing/18 May 2011/p. 4.

140 TJRC/Hansard/Women’s Hearing/Wajir/19 May 2011/p. 3.

141 For a detailed discussion on the formation and evolution of clan identity amongst the Somali, see Lee Cassanelli, The Shaping of

Somali Society (1982).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/volume2a-130522040202-phpapp01/85/Volume-2-a-235-320.jpg)

![256

Volume IIA Chapter FOUR

REPORT OF THE TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION

the time of this meeting, Degodia had surrendered eight rifles and Ajurans 25

rifles.204

329. It was at this point that the District Security Committee decided to act:

After discussion it was resolved that

(a) An immediate joint operation of the Kenya Police, Army and Administration

Police be mounted to be commanded by the OC ‘A’ (COY 7KR) to spread all

over the district to look and arrest the brutal killers of the incidents as per this

(b) Since the killers identification would be difficult as they (killers) could

mingle up with their relatives, sympathizers and harbourers, it was resolved

that all the Degodia tribesmen be rounded up and interrogated with a view

of identifying the killers [for] prosecution.

(c) Since this exercise is a big one, the security personnel in the district will not

be able to cover it adequately, the OC‘A’COY 7KR and OCPD were asked to

request for manpower from their respective superiors.205

330. The District Security Committee also addressed the issue of the so-called inciters of

violence:

The DSC has the view of extending the detention of the four inciters of violence

earlier detained namely:

(a) Abdi Sirat Khalif

(b) Mohamed Ali Noor

(c) Omar Ali Birik

(d) Ahmed Elmi Daudi

And the following new inciters of violence namely:

(a) Garey Omar Dore

(b) Hussein Ali Shoda

(c) Abdi Subdow Noor206

204 See Min 16/84/iii, Minutes of the Special DSC Wajir Meeting held on 9/2/84 in the District Commissioner’s Office Starting at 3.00P

P.M., 9th

February 1984, p. 2

205 See Min 16/84/iii, Minutes of the Special DSC Wajir Meeting held on 9/2/84 in the District Commissioner’s Office Starting at

3.00P.M., 9th

February 1984, p. 2 – 3

206 Mr Abdi Subdow Noor appeared before the Commission on the 19th

of April 2011 in Wajir.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/volume2a-130522040202-phpapp01/85/Volume-2-a-270-320.jpg)

![261

Volume IIA Chapter FOUR

REPORT OF THE TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION

After I learnt of the operation, we continued talking with him [Mr Kibere]. However,

he was just reporting that there was no progress and that they had not recovered any

firearm[s]. He did not say the details of the operation or the outcome of the interrogation.

That was on the 10th

.217

347. A clarification needs to be made. When Ndirangu said that he and Kibere were

“talking”what he actually meant was that they were exchanging coded radio calls:

I stated that communication in the North Eastern Province at the time was very poor

because we depended very much on radio calls. Most of the information, especially

on secret matters, was coded. It was just not transferred like that. It was coded to give

security to the message because there were interceptions from neighbouring countries.

Also some people had some gadgets for intercepting communication between the

security forces on the ground.218

348. During all of this, the Kenya Intelligence Committee was still present in Garissa until

the middle of the morning of 10 February 1984. A three-way Kenya Intelligence

Committee, Provincial Security Committee and Garissa District Security Committee

meeting had been scheduled. All of the participants who testified maintained that

not a word was spoken about the unfolding situation in Wajir. The delegation was

then flown back to Nairobi, with the Provincial Police Officer escorting them back

as the situation in Wajir was escalating.

349. Meanwhile, back in Wajir itself, residents were caught up in a bewildering

whirlwind. Other than security officers patrolling the streets, nobody seemed to

know what was happening and why. After the shock of being awakened and

ferried away from his home in Griftu, Hilowle found himself at the police station

surrounded by scores of equally mystified and, by then, increasingly frightened

men. Hilowle was somewhat fortunate in that as a government employee, he had

non-Somali friends and colleagues, including the officer in charge of the police

station:

The OCS (Officer Commanding Station) who was there told me to sit down. He told me

to sit down and that there was no problem. He told me that it was a government order

that had come from Wajir and above. I sat down because we knew one another. I had

to join my colleagues and sit there. The OCS gave us a brief speech because he also

knew most of the traders who were there, some of the workers who were there, and

most of the local residents who were living there who had all been removed from their

houses at night. He said: “My colleagues, I cannot help you today. There is something

somewhere. You will all go to Wajir and there is something that will be clarified to you.

Screening will be done and you will be screened there.”219

217 TJRC/ Hansard/ Public Hearing/ 2 June 2011/ Nairobi/ p.76

218 TJRC/ Hansard/ Public Hearing/ 3 June 2011/ Nairobi/ p.4

219 TJRC/ Hansard/ Public Hearing/ 18 April 2011/ Wajir/ p.37](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/volume2a-130522040202-phpapp01/85/Volume-2-a-275-320.jpg)

![286

Volume IIA Chapter FOUR

REPORT OF THE TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION

place called Makaror and said:“Today, there are no men for you.We are your men.”

No woman was spared. They did not care whether some were pregnant. They did not care

when some women told them they were about to give birth.They did not care that some women

were old. Every soldier came.They were so many soldiers.They were uncountable.There were no

prostitutes those days, so these men were sexually starved. By then, I was nine months pregnant.

They raped me again and again until my unborn child came out.Twenty women who were raped

died. I saw them with my own eyes.

Some women resisted them. They struggled with them and because of that struggle, they

were beaten to death. During the night, the place became a camp for only women to be raped.

The dead bodies were taken away.We do not know where they took them.

The men’s bodies were taken to Moyale. One day, as I was travelling to Godhane, which is

across the border, I saw two trucks full of skeletons. A man pointed out that to me and said:“Those

are the bones of the Degodia men.”They were also taken to a place called Bandu, which is close

to Marsabit. There is another place called Sahara close to Mandera. There is also another place

called Wajirbora. Our bones were thrown in these places. What remained were the huts. Nobody

questioned whom they belonged to.They just took petrol and set them on fire.We were not intel-

ligent. Those days, women were very poor, but today the state of women has changed. I can see

that we are able to write. By then, the Degodia women were in a desperate state. Even the Kikuyu

women sympathised with us. Other Kenyan ladies came and cried with us. They donated to us

clothes when this calamity befell us.

[…] We could not help ourselves. We were absolutely helpless. All I could see was my father

who was cut into pieces. My father and brother were on top of each other. Both were dead. They

died in a very bad way.We were just watching. No tear could drop out of my eyes that day.Today,

I can cry because there is a change in the situation of women. We did not get any help that day.

We did not get someone to help us.

We lost wealth and relatives, but still we are alive today. We did not feed on the dead bodies

or the carcasses.The government“ate”us that day.

About three months after that incident, we were eating the bark of trees by scratching the

top parts and eating the inner parts, because we could not come to town since we were afraid.

We could not even access health care because they would ask:“Where are you taking this injured

Shifta?”If we told them that our people were massacred in Wagalla, they told us:“You go away.”I

personally remember I went seven times to the police station.They locked me up in prison seven

times. After my child came out prematurely, I screamed. I was shocked. I was mentally disturbed. I

was screaming hysterically every time, so they took me to prison and said that I needed help.They

took me to prison and sent me back after seven days.They had a name for us:“wolves or hyenas.”

Theysaidwedidnothaveanypeople.Theysaidwewerejustroamingaroundingroupsaimlessly.

So they called us“the crazy pack of hyenas.”

As to the calamity that befell us, only God can answer us.We were born in Kenya. I have never

seen any other flag other than the Kenyan flag. I am 67 years old. I used to drink a bottle of milk

which I used to buy for 50 cents in those days. Today if you need a bottle of milk, you buy it for

KSh100. I have lived for that long. What happened to us, I have never heard of it anywhere else.

When we heard about theTJRC we were frightened because we thought that you would identify

those of us with injuries and information and then we would be put in prison. But when we heard

that ladies are part of theTJRC, we felt better because we knew the compassion of women.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/volume2a-130522040202-phpapp01/85/Volume-2-a-300-320.jpg)

![310

Volume IIA Chapter FOUR

REPORT OF THE TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION

2. To scrutinise the instructions given to the Wajir DSC by the North

Eastern Province PSC regarding the incidents which took place in Griftu

Division between 3rd

and 9th

February 1984.

3. To scrutinise all the details of the operational orders which took effect

from 10th

February 1984 and look into how the same were carried out

and by who[m]..

4. To identify the officers responsible for the welfare of the prisoners

while under interrogations and in particular who was responsible for

the supply of food, water and shelter.

5. To look into the methods applied during interrogation.

6. To establish the cause of death of the 29 people and the manner in

which the bodies were handled and disposed of.

7. To gather and analyse any other relevant information related to the

incident.334

493. Etemesi and his team were also asked to:

Make concrete conclusions on all matters pertaining to the incident and recommend any

actiontobetakenonthoseresponsibleforanymisconductoromission.TheCommitteewas

also to propose, if necessary, any changes in the present operational procedures.335

494. The Commission found out that from the outset the Etemesi-led inquiry was different

from its predecessors. Its terms of reference more than suggested that previous

investigations were seen as lacking and limited and that a much more rigorous

approach was needed. Etemesi and his team had a much better understanding of

the outstanding and contentious issues and were thus able to structure their inquiry

accordingly.

495. The outcome was a report that was not only much more detailed than its

predecessors, but also much more probing. After a quick (and conventional)

assessment of the underlying ethnic and political situation in Wajir District,

Etemesi zeroed in on the critical issue of the actual operation. Etemesi uncovered

the trail of signals that emanated from Wajir and Garissa on the 9th

and the 10th

of

February. He even attached copies of the actual signals to his report. As directed by

the terms of reference, the team then directed their attention to the situation on

the field itself. He uncovered facts that no witnesses in the present - Tiema, Kaaria

and others - spoke about candidly:

334 Report of a committee appointed to investigate circumstances leading to the recent unrest in Wajir District and the way government

officials handled the issue, 15th

March 1984, 1-2.

335 Report of a committee appointed to investigate circumstances leading to the recent unrest in Wajir District and the way government

officials handled the issue, 15th

March 1984, 2.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/volume2a-130522040202-phpapp01/85/Volume-2-a-324-320.jpg)

![317

Volume IIA Chapter FOUR

REPORT OF THE TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION

512. Ruto stood firm and unyielding from the position that the government had held

for the past 16 years. The Wagalla operation had already been investigated to the

satisfaction of the government by the Etemesi team:

Mr Temporary Deputy Speaker Sir, in good faith, in February 1984, indeed a committee

was appointed to investigate the circumstances that led to that incident. It was that

committee that, that particular incident was in fact for. Mr Temporary Deputy Speaker

Sir, I was saying that indeed a committee was appointed then. In fact, it was that

committee’s [recommendation] that the then North Eastern Provincial Commissioner

(PC) be dismissed from government service.

I think it was not possible for the government to take any more drastic action than what

was taken then because the provincial administration personnel in that area then were

facing threats on their lives from the perpetrators of insecurity incidents. I believe the

best was done out of that situation.354

513. The exchange between the Assistant Minister and other MPs ended on a premature

and entirely unsatisfactory note for those interested in re-opening Wagalla. The

Speaker shut down the debate and moved on to the next question. The Etemesi

report’s status as the primordial source of government information and investigation

on Wagalla remained intact.

Military board of inquiry

514. As the Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission (TJRC) was being established in

2009 to investigate, among other things, the Wagalla Massacre, a board of inquiry

was established within the military to undertake an audit of those issues involving

themilitarythatfellwithintheCommission’smandate.Despiteanumberofattempts,

the Commission was never able to secure a full copy of the report of that board of

inquiry. It is possible that the TJRC was to receive the report, or at least a summary

of its contents. When the Commissioners paid a courtesy visit to the Kenya Defence

Forces(KDF)apresentationhadbeenpreparedforus.Ambassador(Bethuel)Kiplagat

(the TJRC Chairman), then left the room with the officer in charge to have a private

conversation, after which the presentation was cancelled.

515. Although the Commission never received a full copy of the report prepared by

the military in preparation for the Commission’s work, it did secure a copy of that

section of the report devoted to the Wagalla Massacre.355

It is a remarkably candid

document, at times acknowledging clear violations of the rights of the residents

354 Kenya National Assembly Official Record (Hansard) 18th

October 2000, 2190

355 The section of the report provided to the Commission is titled “Wagalla Incident – 1984,” and consists of pages 42-46, and

paragraphs 100 to 120, of the larger report.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/volume2a-130522040202-phpapp01/85/Volume-2-a-331-320.jpg)

![318

Volume IIA Chapter FOUR

REPORT OF THE TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION

of Wajir, suggesting strategy for dealing with the Commission’s inevitable inquiry

into the matter, and concluding with lessons learnt.

516. The military board’s narrative was similar to that of the earlier inquiries: a brief

history of the conflict between the Degodia and Ajuran; the efforts to disarm both

clans; and the ensuing operation that resulted in a number of dead. There were

three significant, and for the Commission important, differences between this

narrative and all of the previous ones made available to the Commission. First, the

report for the first time introduced national security as an element of concern that

gave rise to the operation. Second, and related to the first point, the report for the

first time introduced two additional institutions as players in the Wagalla saga: the

National Security Council (NSC) and the Kenya Intelligence Committee (KIC). Third,

the report was candid and up front about how the operation was conducted in

a way that violated the constitutional and human rights of the Kenyan citizens

caught up in it.

517. In the background to the analysis of the Wagalla Massacre, the report quickly

noted the national security concerns raised by the conflict between the Degodia

and Ajuran, recording that “[t]he rivalry between the two clans was threatening

national security because of the foreign Degodia militia that had infiltrated Wajir

West from Somalia following the events in that country….”356

The report then

sets out in detail how the highest levels of the national security apparatus of the

government was brought to bear on this problem:

[T]he National Security Council (NSC) held a meeting in Nairobi in Jan 84 where it was

decided that all male Degodia be disarmed by force. The NSC further resolved that the

NEP Security Committee (NEP SC) study and forward recommendations as to how this

was to be realized. On 25 Jan 84, the PSC met in Garissa under the chairmanship of Mr

Benson Kaaria PC NEP to consider the requirements of the NSC. The Acting Wajir DC

Mr M M Tiema was charged with the responsibility of carrying out the operations. The

Kenya Intelligence Committee (KIC) accompanied by the PSC NEP visited Wajir on 8 Feb

84 where they were briefed on [the] security situation in the district during their NEP

tour.

On 9 Feb 84, A Special Wajir DSC was convened at Wajir DC’s office under the

chairmanship of the Acting DC. The meeting resolved to carry out an operation with the

objectives of disarming the Degodia and force them to provide names of bandits who

were committing crimes in the district. Once the operation was authorities, it began in

earnest on 10 Feb 84 at 0400 hrs and it involved the Police, the Administration Police

and the Armed Forces. The operation covered Elben, Dambas, Butehelu, Eldas, Griftu,

and Bulla Jogoo villages.357

356 Army Board of Inquiry, “Wagalla Incident – 1984”, para 101.

357 Army Board of Inquiry, pp. 42-3, para. 103.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/volume2a-130522040202-phpapp01/85/Volume-2-a-332-320.jpg)

![320

Volume IIA Chapter FOUR

REPORT OF THE TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION

521. While the earlier reports indicated some missteps by members of the provincial

and district administration, this more recent report for the first time evaluates the

effects of the operation on the rights of the victims.The Etemesi report, for example,

criticized the unprofessionalism of those involved in the operation, the lack of clear

operational guidelines, and other problems related to the implementation of the

operation as it related to its success. At no point did the Etemesi report, or any

of the previous reports, indicate that the rights of those affected may have been

violated, much less that any efforts should be made to compensate or otherwise

provide reparations to such victims.

522. Finally, the Army Board inquiry notes that“[t]here is need to harmonize the evidence

to be given to the TJRC with other security agencies as the disparity affects the

credibility of the evidence.”360

It was not clear to the Commission what was meant

by “harmonizing” the evidence. There may of course be value in different agencies

and witnesses comparing their notes and assisting in their recollection and

reconstruction of events that occurred almost three decades ago. There is, of course,

a fine line between such efforts aimed at unearthing a more accurate truth about

the past, and efforts to create a common story of the past that may brush over or

suppress certain inconsistencies or other facts in a way to conceal the truth of what

happened. As the Commission notes below, there was other evidence suggesting

that some of those involved in the Wagalla operation attempted to harmonize their

evidence in a way that distorted or even hid the truth.

The Wagalla dead

523. Sitting at the heart of the Wagalla story is the still painful issue of the loss of life. For

survivors and victims alike, no other aspect of the operation generated as much

sorrow and anger. And as the Commission tracked down documents, pored over

reports and heard testimonies, it became increasingly clear that the one question

that most people wanted addressed was, quite simply: how many died in Wagalla?

While the question is simple and straightforward, the answer is not. As with Bulla

Karatasi and Malka Mari, the Commission’s inquiries uncovered wildly different

understandings of the Wagalla dead.

Fifty seven (57)

524. The official death toll for the Wagalla operation has been given as 57. While it is

clear that the death toll was greater – even the recent military inquiry puts the toll

at least 300 and perhaps as high as 1,000 – the government has never officially

revised the figure of 57. The Commission went to great lengths to understand the

360 Army Board of Inquiry, p. 46, para. 119.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/volume2a-130522040202-phpapp01/85/Volume-2-a-334-320.jpg)

![327

Volume IIA Chapter FOUR

REPORT OF THE TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION

Mr William Samoei [Ruto]: …I confirm that 13 people were shot dead at that particular

incident but in total, 57 and not 5 000, as the Hon Member is alleging, died as a result

of that exercise.375

544. Moments later, Ruto was back on his feet with yet another submission on the

Wagalla numbers:

I still maintain that 57 people died as a result of that incident. Indeed 13 people were

shot dead and the rest died from excessive sunshine.376

545. At 8.20pm that evening, the BBC News website published a story under the

heading“Kenya admits mistakes over‘Massacre’”.377

The item, a brief one, reported

the Wagalla debate that had taken place only a few hours before:

The Kenyan government has for the first time admitted making mistakes 16 years ago

when hundreds of ethnic Somalis were killed in the north-east of the country. A Kenyan

minister in the Office of the President, William Ruto, told Parliament that 380 people had

died in what's been called the Wagalla massacre, which took place during a drive by the

security forces against shifta bandits. Previously, the government had said that only 57

people had died. The parliamentarian who raised the issue, Ellias Barre Shill, said the

minister was trying to avoid crucial questions as he charged that more than 1 000 ethnic

Somalis were victims of the killings.

546. The Commission found that this BBC report was the prime source of the incorrect

claim that the government officially changed the death toll from 57 to 381.

Hansard records from the 18th

of October quite clearly show that Mr Ruto made no

such revision. He stuck to and indeed repeated Etemesi’s long-standing estimate

of 57 dead. Furthermore, the BBC website was the first and only news outlet to

report Ruto’s contributions to the debate in this manner. No local newspapers

repeated this claim when they went to press the following day. The Daily Nation

portrayed the debate as heated and disbelieving of the minister’s submissions

but made no mention whatsoever of 381 dead:

Mr Ruto told the House that 381 suspects were held to be screened for gun-holding,

but he angered members when he said 13 of them were shot dead and a further 44 died

in the ensuing commotion.378

547. What the BBC did report accurately was Ruto’s admission in Parliament that the

operation had not been handled correctly:

The chronology of events that led to this unfortunate incident speaks for itself.The arrest

and rounding up of those people and their presence at Wagalla Airstrip was as a result

375 Kenya National Assembly Official Record (Hansard) 18th

October 2000, 2189

376 Kenya National Assembly Official Record (Hansard) 18th

October 2000, 2190

377 Kenya Admits Mistakes Over ‘Massacre’, 18th

October 2000 available at http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/978922.stm

Accessed 25th June 2011.

378 ‘Wagalla issue causes uproar in the House’ Daily Nation 19th

October 2000, 17.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/volume2a-130522040202-phpapp01/85/Volume-2-a-341-320.jpg)

![329

Volume IIA Chapter FOUR

REPORT OF THE TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION

193 bodies spread out over a number of locations, including Sarmanta in Griftu

and in Tarbaj. The specificity of his count came, he says, from grouping the dead

bodies into batches of 25 to facilitate the taking of the photographs that Khalif

attempted to table before Parliament in March 1984:

Then we looked for the dead bodies. Abdirizak told me to put the dead bodies in

50s. So, after we arranged 50 bodies, Abdirizak said that if I take 50 bodies in one

photograph, they would not fit in [the frame of] one camera. So, he said that we

arrange and put them in 25s in one snap shot. I tried to arrange the dead bodies

putting them in rows and Abdirizak was taking the snap shots of the bodies. We got

193 bodies. I tried to arrange the bodies in 25s…we arranged 193 bodies and then we

started taking snapshots.383

551. The pictures that Abdille said he helped to take were later discredited as staged by

disbelieving parliamentarians. The fundamentals of Abdille’s story have, however,

remained constant: he personally knows of 193 dead.

552. Most recently, the Wagalla Foundation Trust has emerged with an estimate of

475 dead.384

The trust divides this estimate into two sections. The first section

consists of a list of 335 people who were said to have died between the 10th

and the 14th

of February. These 335 were primary victims of the operation itself.

The second section consists of 140 people who died from injuries and medical

ailments attributed to Wagalla. The foundation’s estimates spring from a deep

and intimate knowledge of both Wajir and Wagalla, as well as a direct experience

of the operation as both victims and survivors.

553. The conundrum for the Commission was the continuing insistence that the

total number of people rounded up during the operation was just 381. The first

note of a specific number of detainees, 381, appeared in the minutes of the PSC

meeting of 15th

February.385

The number of detainees remained unvaried through

the various reports and investigations including the Etemesi-led inquiry.

554. Three hundred and eighty one detainees cannot be reconciled with estimates of

several hundred dead; either the death toll was lower or the number of detainees

was higher. The Commission received testimony to easily support both possibilities.

Fifty seven is of course the long-standing and much discussed official death count.

The notion of just 381 men rounded up was consistently challenged by witnesses

and survivors who gave estimates of 3 000 to 4 000 people crammed into the field.

In Wajir itself, the Commission heard from Abdulrahman Elmi Daudi, a former army

corporal, who remembered hundreds of men arriving at the airstrip by foot and in

383 TJRC/ Hansard/ Public Hearing/ 18 April 2011/ Wajir/ p.61-62

384 Families and Survivors Wagalla Massacre Lists of Victims, 29th

March 2012, TJRC-NAIROBI

385 Min. 20/84., Minutes of the Special North Eastern Provincial Security Committee Meeting held in the Provincial Commissioners

Office on Wednesday 15th

1984 beginning at 9.30.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/volume2a-130522040202-phpapp01/85/Volume-2-a-343-320.jpg)

![335

Volume IIA Chapter FOUR

REPORT OF THE TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION

The photographs

571. Several accounts of the Wagalla dead make reference to photographs of some

of the dead bodies. Abdille’s testimony was that he was directly involved

in the taking of a series of pictures in and around Wagalla and beyond. The

circumstances, as Abdille explained, were dramatic as he and his partner, a man

known as Abdirizak, sought to document the scene to avoid being detected by

the authorities:

Abdirizak and I were told to leave town and take the vehicle and a camera, so that we

go and get photographs of the bodies which were thrown in the countryside. We were

to come with photographs that were to be used as evidence or to be shown to the

international community. Three of us were told to bring as many photos as possible.

We looked for a camera but we did not get a camera to buy. We went to the American

volunteer teachers who were in Sabunley and also those from Norway helped us.

Norway is the only country in the world that reacted to what happened in Wagalla. We

went to the American volunteer teachers and got different cameras and there was one

that could take 48 photos. The issue was that if the police saw you with the camera,

they would have killed us. We got three cameras from them. We asked women who

brought milk to town to help us to hide the cameras in the container. Then I put water

on the car. We decided to cheat the police that this was water that we were taking

to the people living in the outskirts. Then we met with the ladies who we had given

the cameras. Then we looked for the dead bodies. Abdirizak told me to put the dead

bodies in 50s. The bodies were there for 9 days and so parts of the bodies had been

eaten by vultures and hyenas. I tried to put the head onto the other parts of the body.

After we arranged 50 bodies, Abdirizak said that if I take 50 bodies in one photograph,

they would not fit in one [frame of the] camera. So, he said that we arrange and put

them in 25s in one snap shot. I tried to arrange the dead bodies putting them in rows

and Abdirizak was taking the snap shots of the bodies. We got 193 bodies. I tried to

arrange the bodies in 25s.399

572. The Commission believed that the idea to take the pictures came from Sister

Annalena, the Norwegian volunteer, and others involved in the search, rescue and

retrieval of the bodies. But it was not possible to ascertain when the pictures were

taken and if they were all taken in the same location. It was also not established

about how many pictures were taken. The story of the pictures’ distribution is

equally dramatic. Still fearing discovery, Abdille and Abdirizak waited for several

days before taking action. They first hid the pictures and negatives in a torch that

had the batteries removed. They then had to find a way to leave Wajir without

raising suspicion:

399 TJRC/ Hansard/ Public Hearing/ 18 April 2011/ Wajir/ p.61-62](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/volume2a-130522040202-phpapp01/85/Volume-2-a-349-320.jpg)

![336

Volume IIA Chapter FOUR

REPORT OF THE TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION

For six days, our car could not come to town. We sent somebody on a donkey cart to

bring us petrol because if we came to town, we would have been arrested. We had to

hide the cameras and the photos. We were told to take the photos to Ahmed Khalif who

was in Nairobi. We gave out the photos to Ahmed Khalif and he then took the photos to

Parliament. He took the photos and said that they were documents of Parliament.We tried

to process the photo. Abdirizak and I took a torch and removed the batteries and put the

negatives into the torch and then we went somewhere; there was a car that ferried goats,

so we hid the torch inside that lorry and that is how we took the photos to Nairobi.400

573. Abdille also described efforts to get the pictures to consulates and diplomatic

missions:

We were hiding in Nairobi. He [Ahmed Khalif] gave the photos to a man and they were

processed. Then the embassies in Ethiopia were given the photos. That is how the world

knew about Wagalla.401

574. Other sources suggested a different scenario whereby the pictures and written

documents were somehow smuggled out of Wajir by Sister Annalena herself to

people like Barbara Lefkow, the American diplomat’s wife. Eventually, the pictures

got to AMREF’s Flying Doctors Service well known for its work in remote and

inaccessible parts of Kenya. At AMREF the pictures came to the attention of Nancy

Caroline, a specialist in emergency medicine and the agency’s chief medical officer.

In a sequence described above, Caroline then began to organise for medicine and

other supplies to be sent to Wajir, and arranged an unofficial visit to Wajir.

575. This report describes the ambiguous reception that the photographs were given

in Parliament when Ahmed Khalif attempted to table them in March 1984. Some

members dismissed the images as staged. The pictures themselves then seemed to

disappear entirely. Unable to table them before Parliament, Khalif appeared to have

simply held onto them as part of his own personal records and documentation. As

far as the Commission could tell, it appears they were never shared with newspapers

or any other media outlets or if they were, the newspapers declined to publish them.

576. The Commission, however, saw and acquired two images of body dumps inWajir in

1984. The pictures came to light as a result of recent interest and research into the

life and work of Sister Annalena Tonelli and Dr Nancy Caroline.402

Dr Caroline died

in 2002. Her personal papers and records are housed at the Schlesinger Library at

Radcliffe College, which is part of Harvard University in the United States. And it is

from her collection that the following pictures were drawn.

400 TJRC/ Hansard/ Public Hearing/ 18 April 2011/ Wajir/ p.62

401 TJRC/ Hansard/ Public Hearing/ 18 April 2011/ Wajir/ p.62

402 Karen Smith, Massacre in Wajir, 1984: Western Relief Organizations Clash with Government Authorities in Post-Colonial

Kenya. Geographies of Volunteerism and Philanthropy II, Association of American Geographers, 25th

February 1984,

New York City](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/volume2a-130522040202-phpapp01/85/Volume-2-a-350-320.jpg)

![339

Volume IIA Chapter FOUR

REPORT OF THE TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION

and confusion made the officers unable to verify what took place at the airstrip and how

many people died…406

583. Etemesi’s raking of the District Security Committee ended in his description of the

Wajir group as “cowardly” and irresponsible for their abrupt departure from the

field in the wake of the shooting:

The committee also observed that, after the shooting incident, the DSC did panic and

the Acting DC, Deputy DSBO and OCPD immediately left the area without due concern

of what was happening. This cowardly move and lack of any sense of responsibility left

the situation to get out of hand, since only the junior officers were left in the area; that

is the Army soldiers and Police Sergeant.407

584. Upon its completion in the middle of March 1984, the Etemesi report was absorbed

into the Office of the President. Then Permanent Secretary in the Office of the

President James Mathenge clearly remembered receiving the document and

studying it for its recommendations.

585. The centrality of the District Security Committee to the action meant that it could

not escape Etemesi’s gaze. As such, Tiema and his men featured prominently in the

recommendations:

To avoid any adverse effect the incident may have on the locals and the civil servants, the

committee recommends that small-scale transfers be effected. The officers, especially

Officer Commanding Army Unit atWajir – Major Mudogo, Acting DC MrTiema and OCPD

Mr Wabwire should be given severe reprimand departmentally.408

586. Simply put, the DSC members had to leave on account of their failures during the

operation itself as well the destabilising impact that their continued presence

might have in Wajir. These recommendations had been presented to, and found

agreement with, President Moi himself. In a telegram dated 29 March 1984, the

British High Commissioner noted:

Moi said that those involved [in the Wagalla Massacre] had greatly exceeded their

authority and the operation had got out of control. MPs had greatly exaggerated

the scale of the trouble and the numbers of deaths but this did not excuse what had

happened. He particularly criticized the Provincial Commissioner Benson Kaaria….

and said that a number of people involved would be removed and replaced. 409

406 Report of a committee appointed to investigate circumstances leading to the recent unrest in Wajir District and the way government

officials handled the issue, 15th

March 1984, 16.

407 Report of a committee appointed to investigate circumstances leading to the recent unrest in Wajir District and the way government

officials handled the issue, 15th

March 1984, 18.

408 Report of a committee appointed to investigate circumstances leading to the recent unrest in Wajir District and the way government

officials handled the issue, 15th

March 1984, 19.

409 Tel No. 431 of 29 March 1984 to Priority FCO from Allinson.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/volume2a-130522040202-phpapp01/85/Volume-2-a-353-320.jpg)

![349

Volume IIA Chapter FOUR

REPORT OF THE TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION

614. Mwiraria, for example, echoed the other members of the KIC that the purpose

of their trip to North Eastern Province was limited to development. Under

questioning, however, he admitted that he had come to that conclusion only after

having reviewed one set of minutes from May 1984 that provided a summary of

the KIC tour that took place three months earlier, and based upon “the little I

could remember.”432

As Mwiraria made it clear to the Commission, the little he

could remember had been aided by the meetings he had attended in his lawyer’s

office with the other members of the KIC prior to the Commission’s hearings.

615. Curiously, the summary of the KIC tour dated 24 May 1984 and that was relied

upon by Mwiraria and others to argue that the tour was limited to development

issues itself refers often to issues of security. For example, the report notes that the

meeting with the DSC in Mandera“dwelt on the security situation in the district and

the border area with Somalia and Ethiopia.”433

More importantly, and surprisingly

given the testimony of Mwiraria and others, these same minutes described the

briefing made by the Acting DC (Tiema) to the KIC in Wajir as focusing on “the

security situation in the district.”434

616. The Commission was particularly surprised that Ambassador Kiplagat in his

testimony repeatedly insisted that the KIC tour was limited to development

issues and did not have security issues in the region as one of its objectives. It

was not lost to the Commission, however, that earlier on when issues relating

to his suitability as Chairperson of the Commission were raised, Ambassador