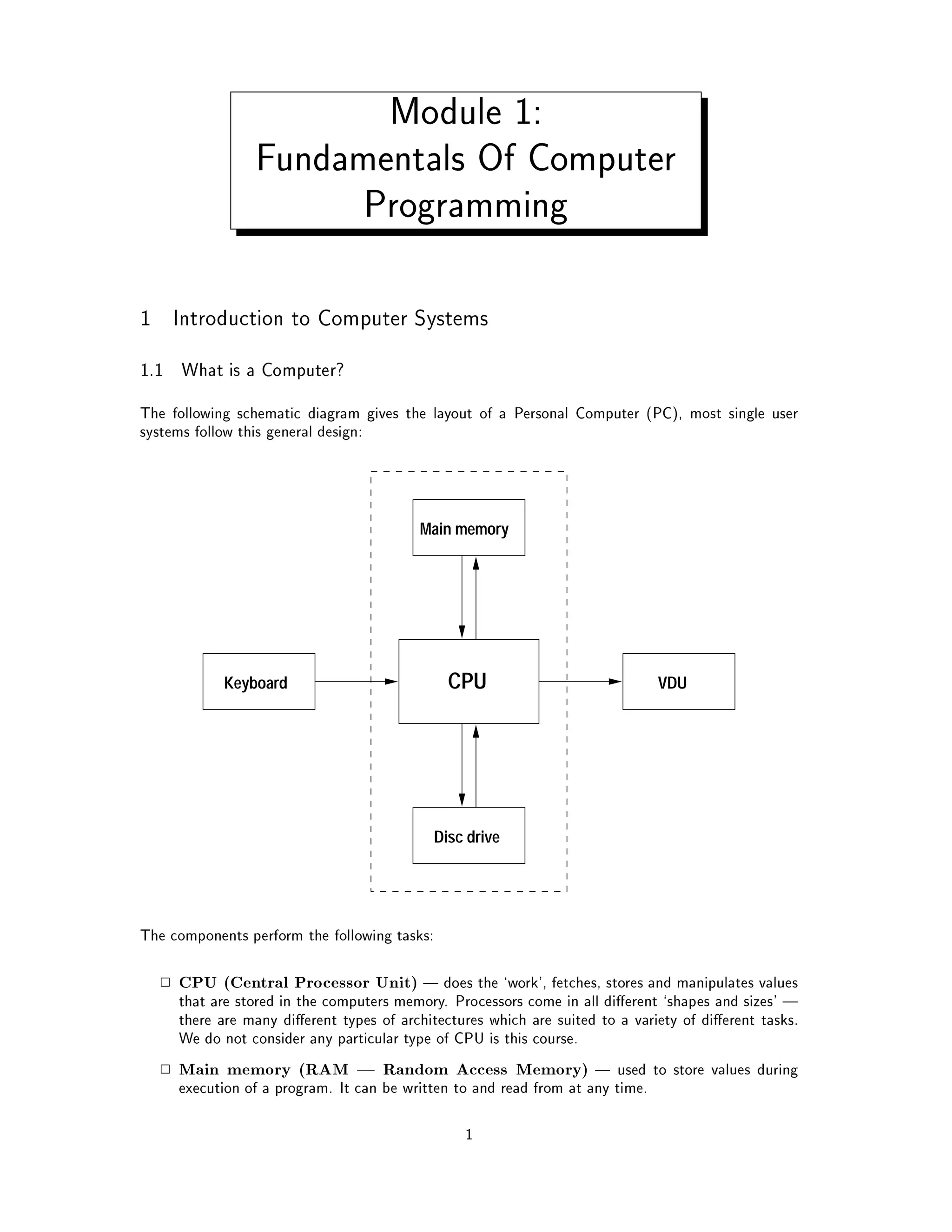

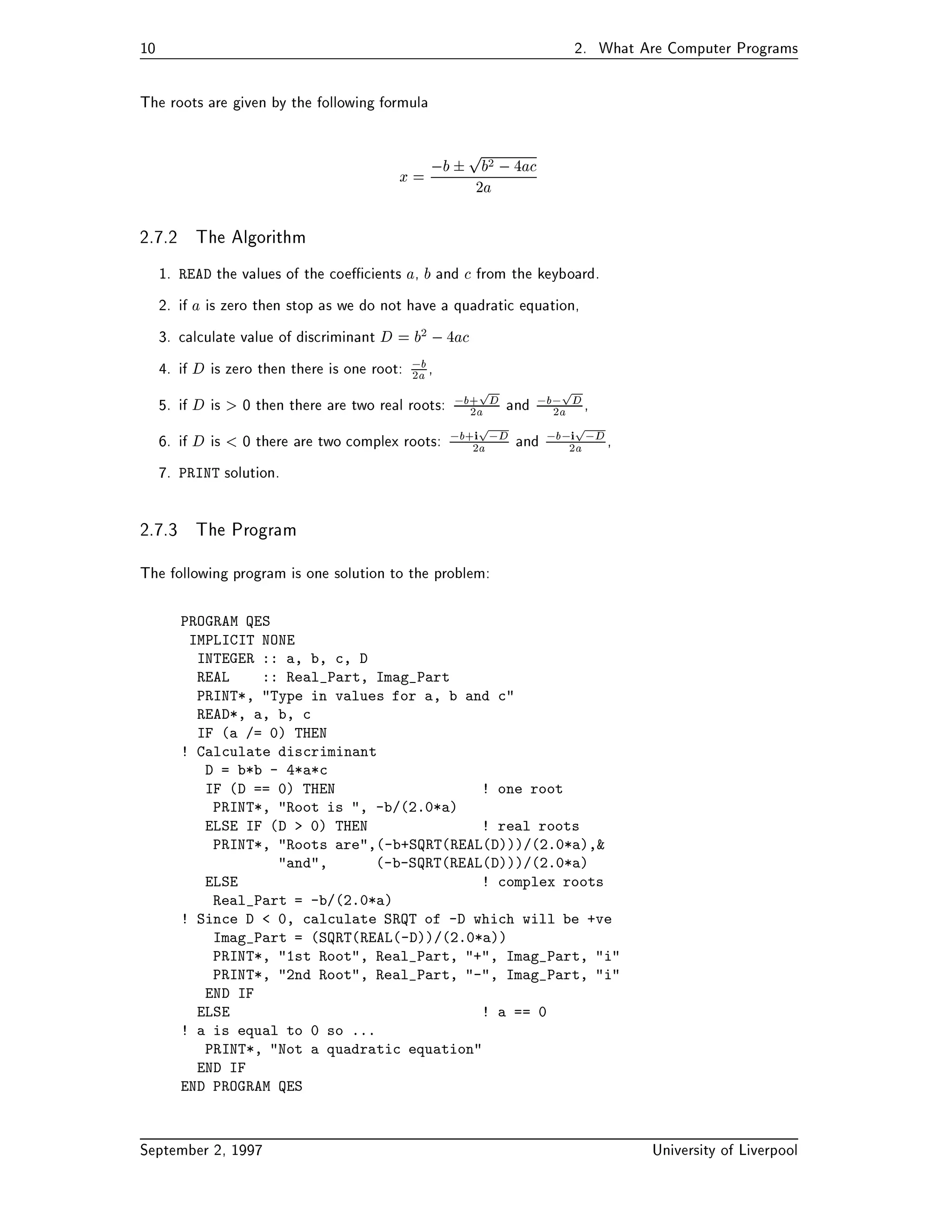

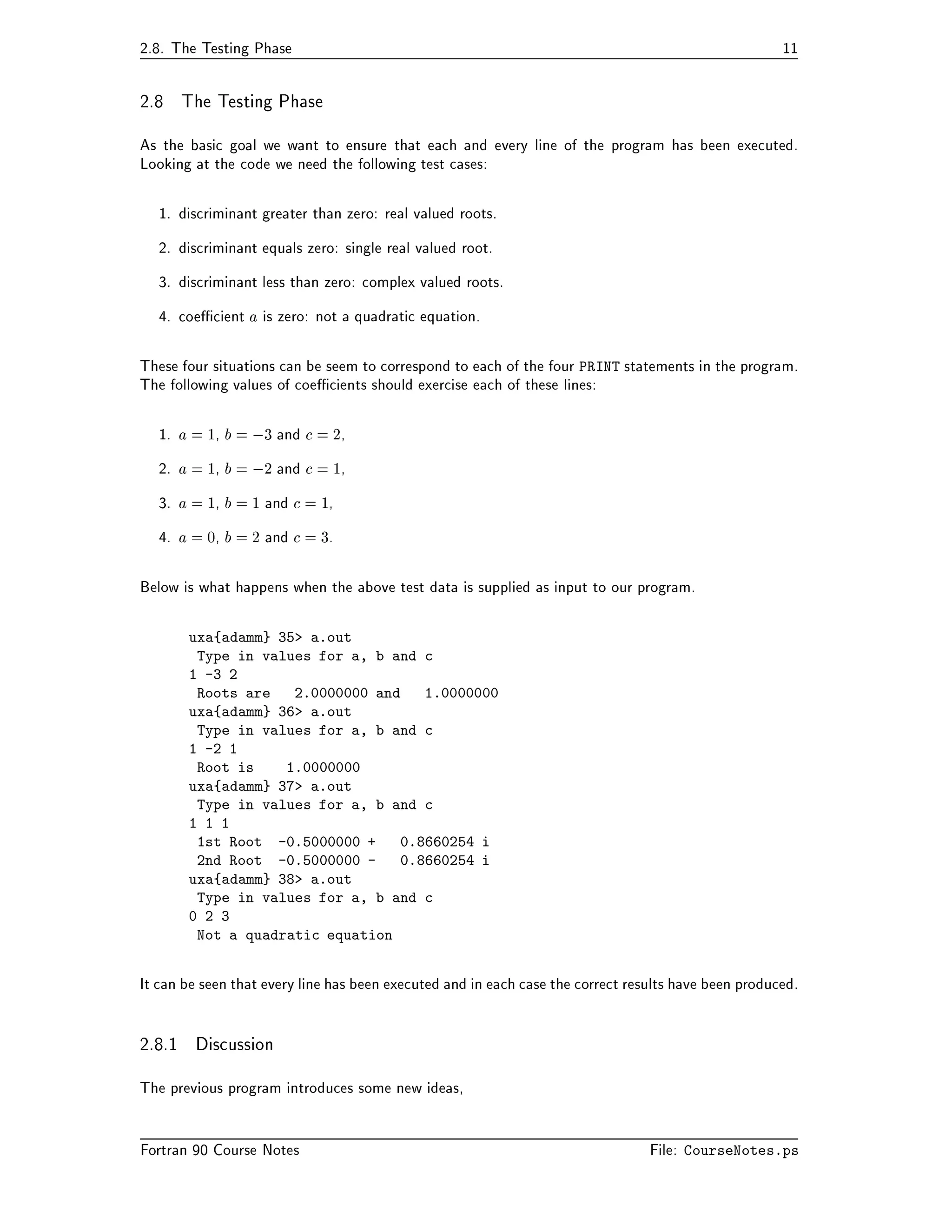

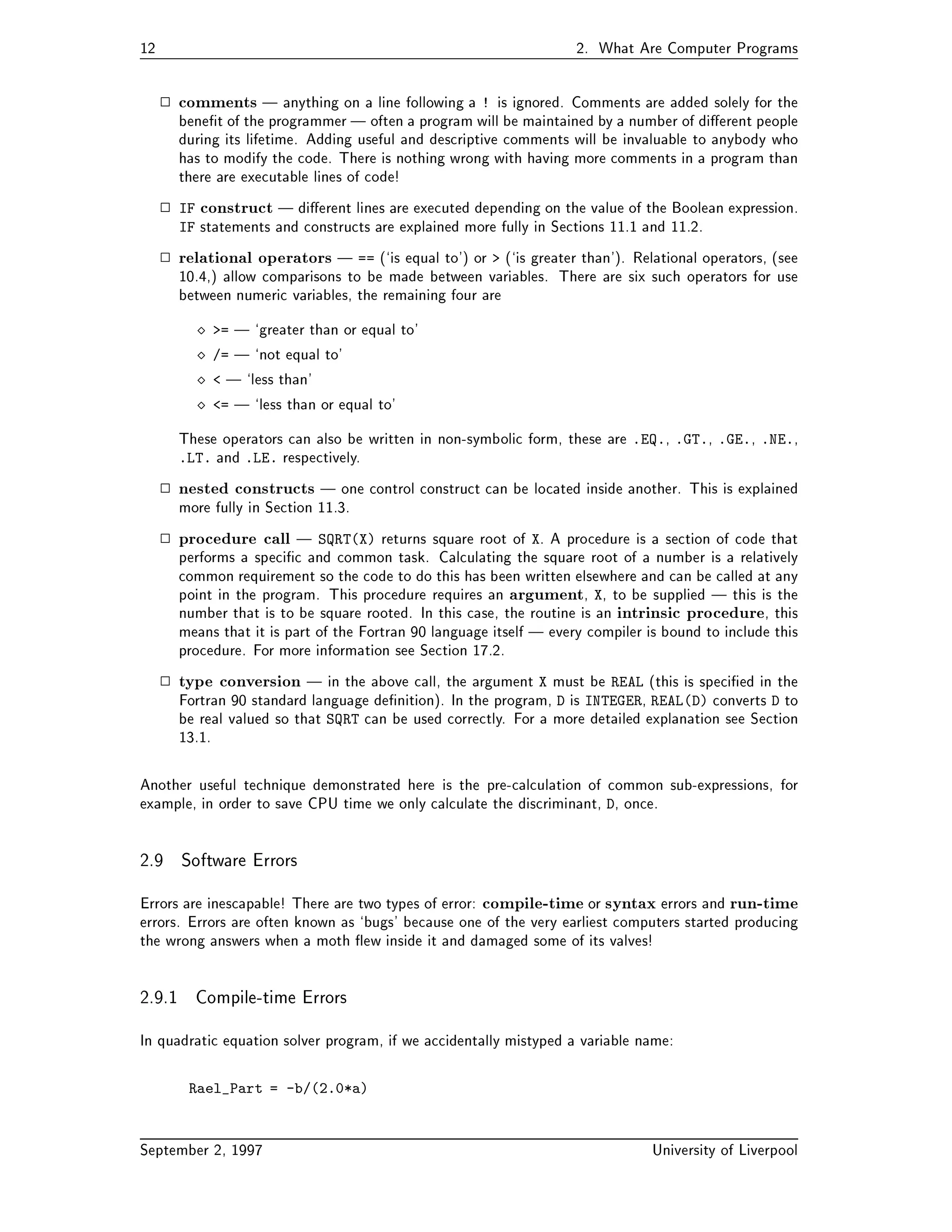

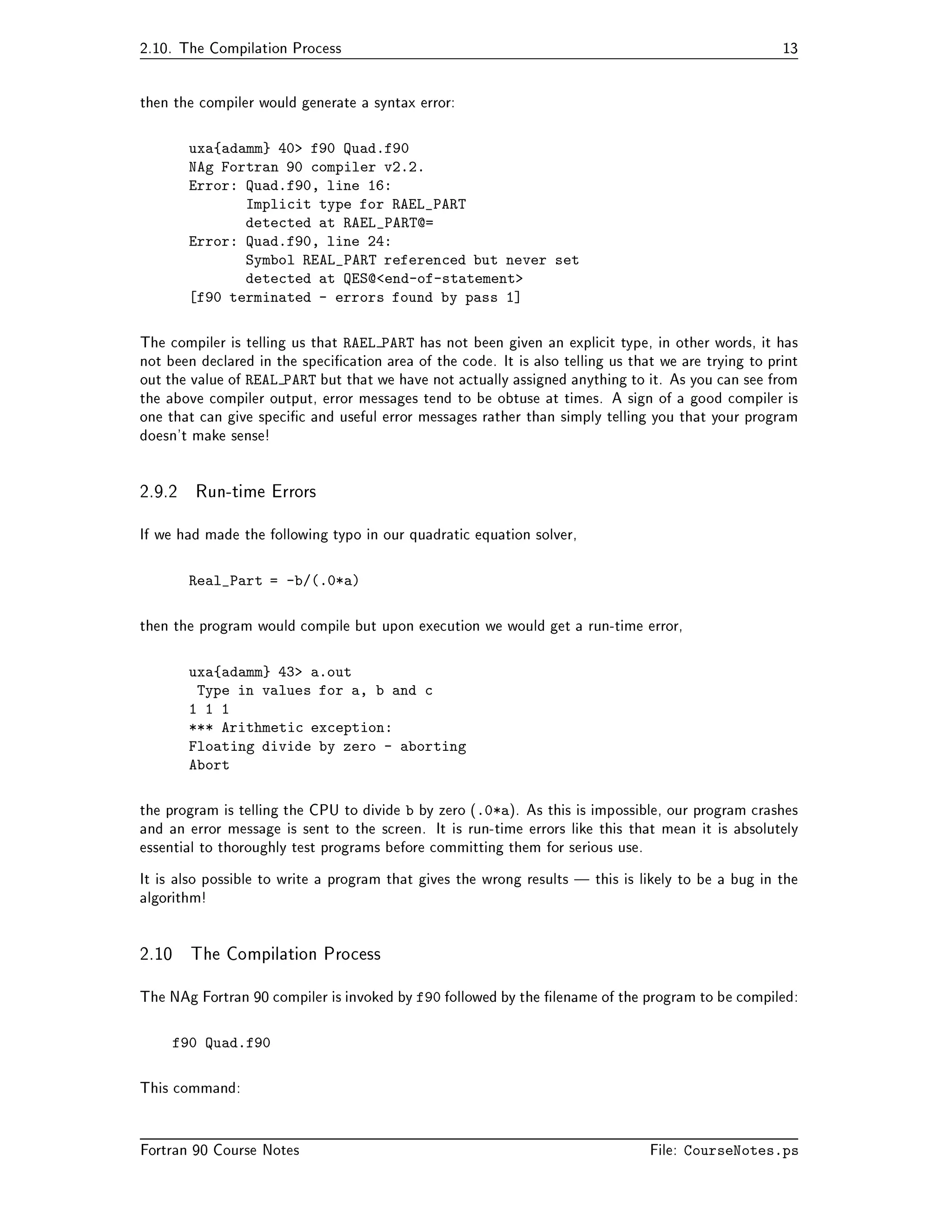

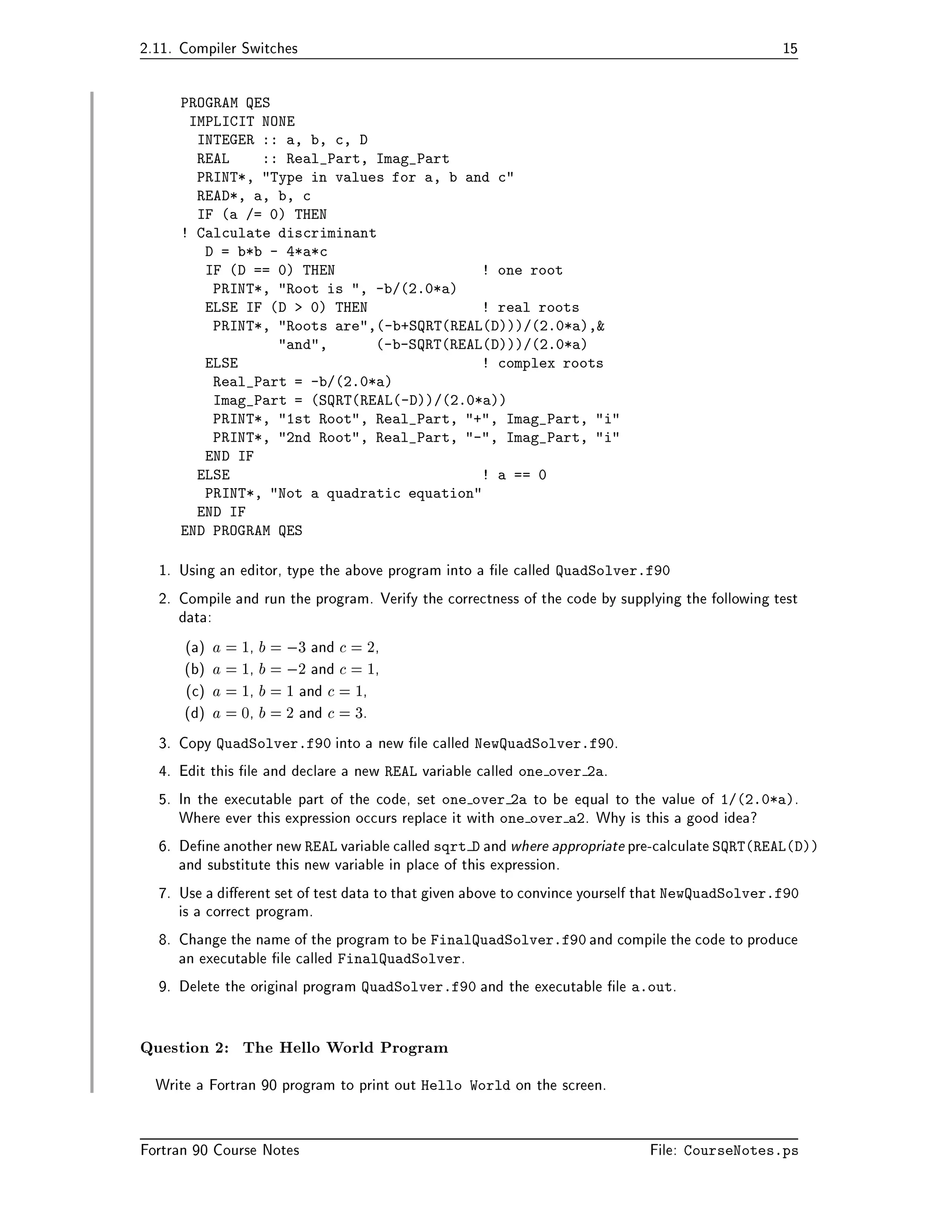

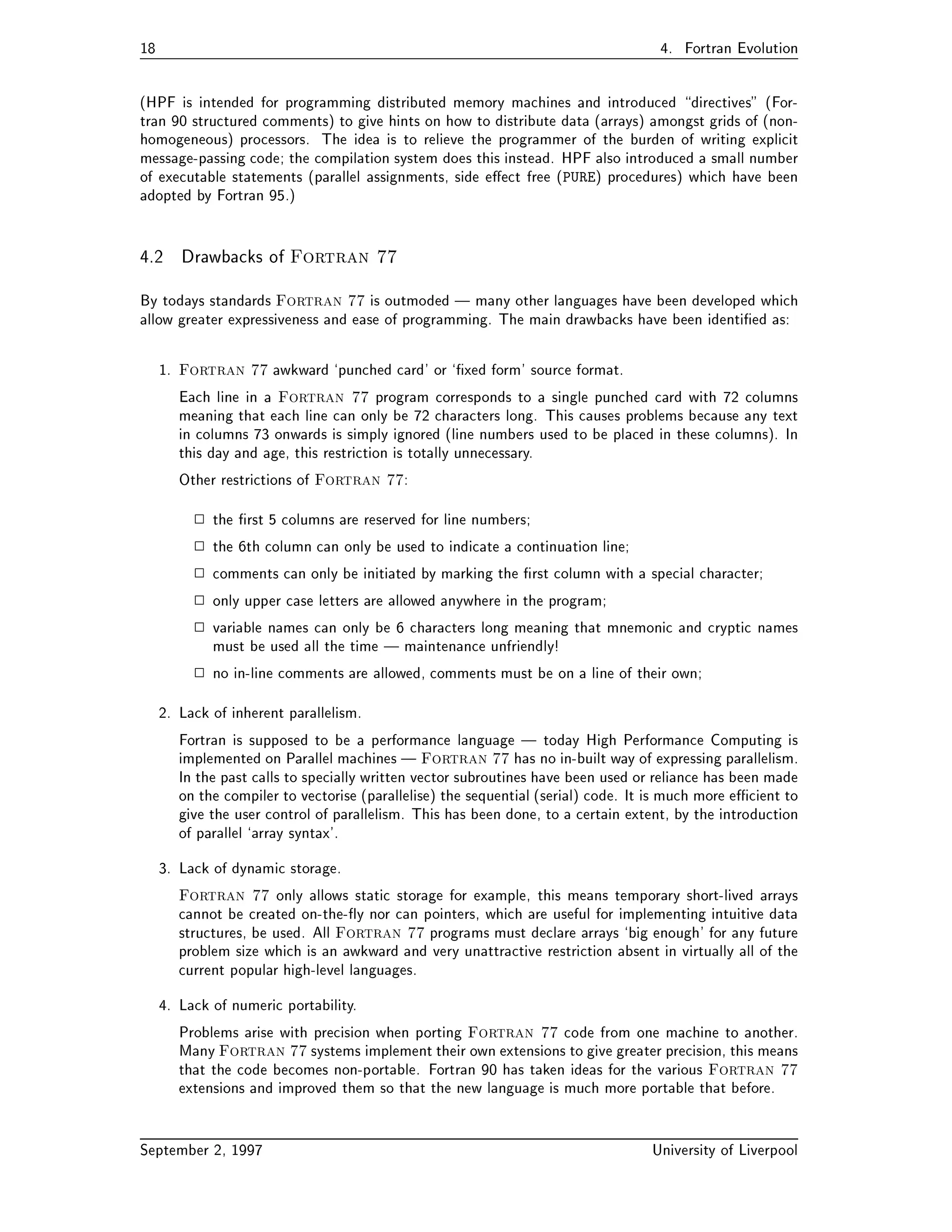

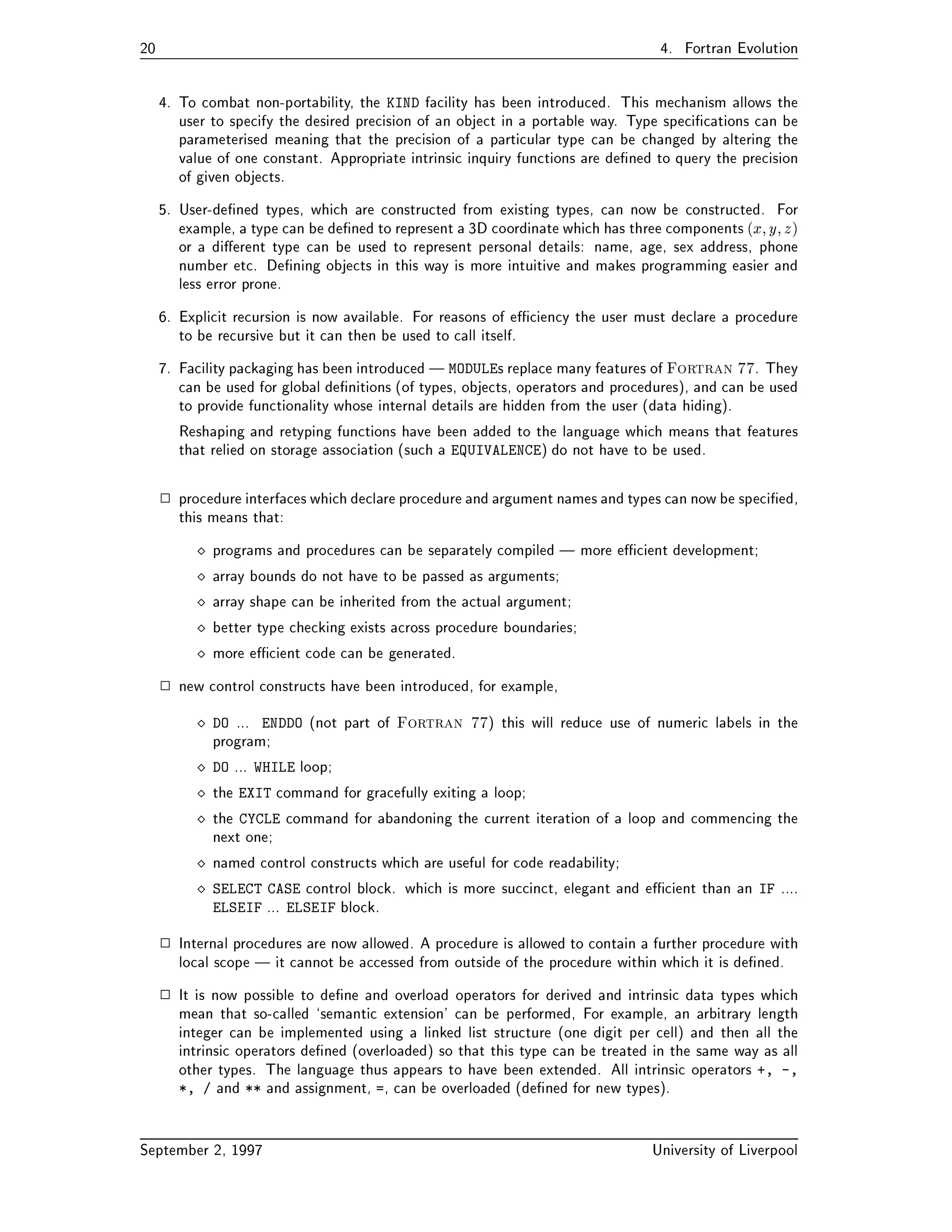

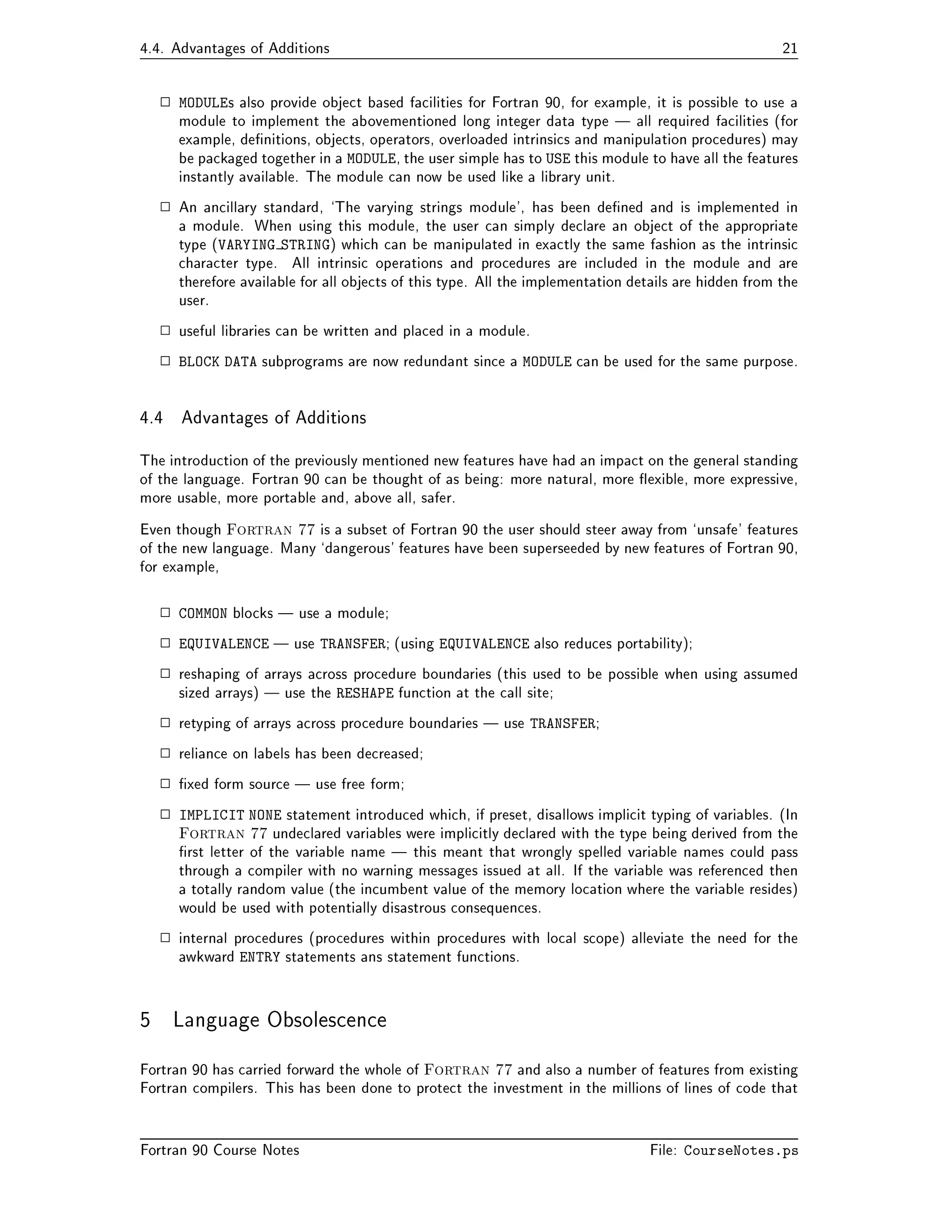

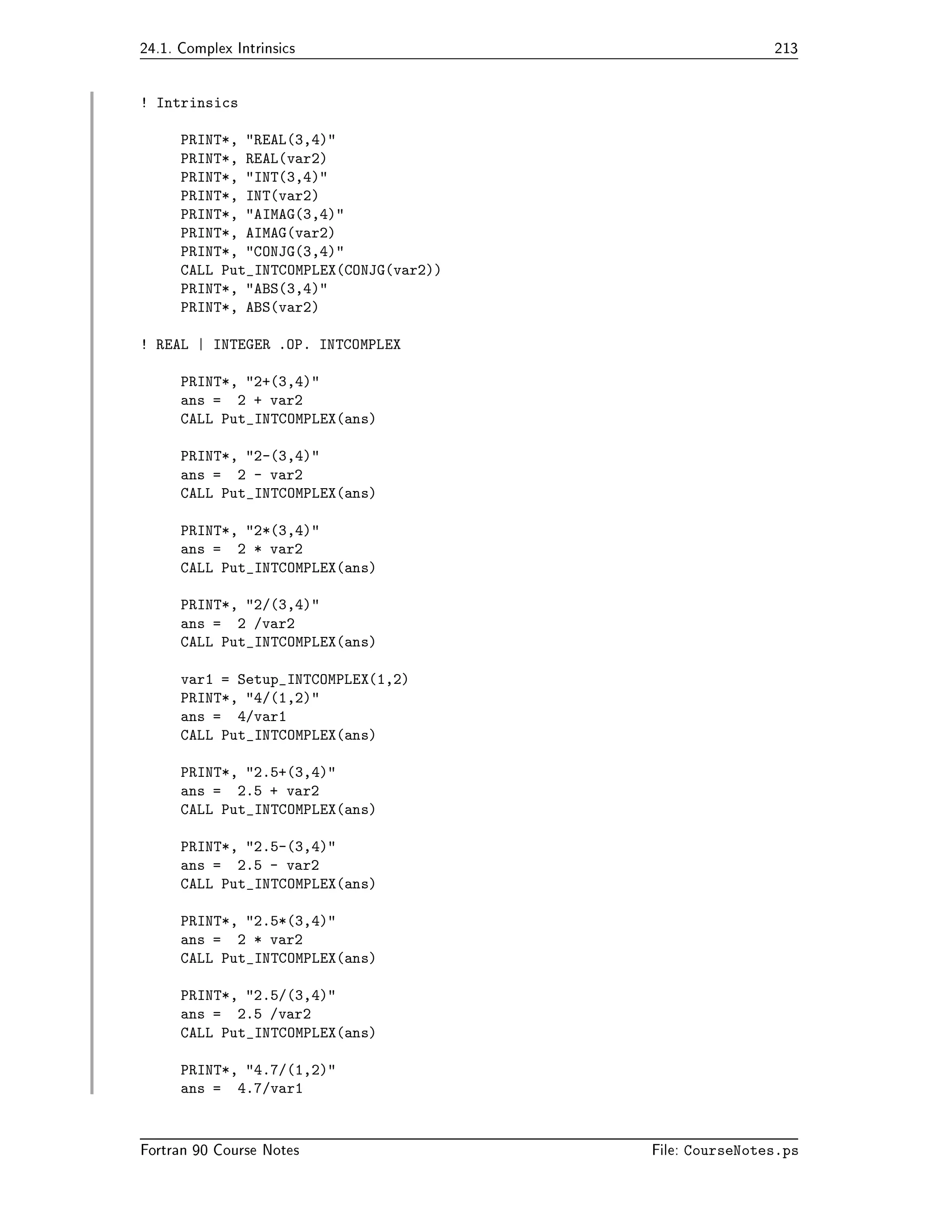

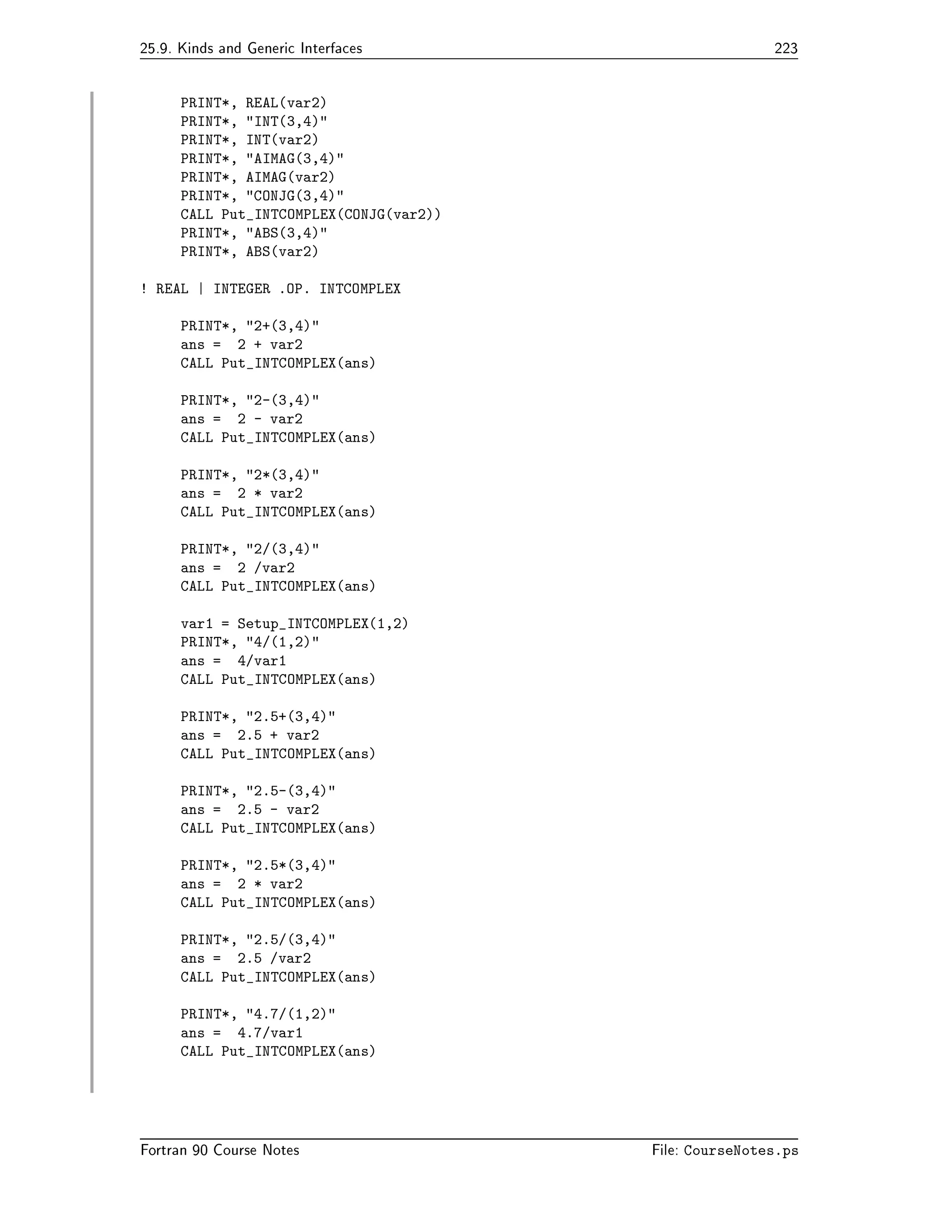

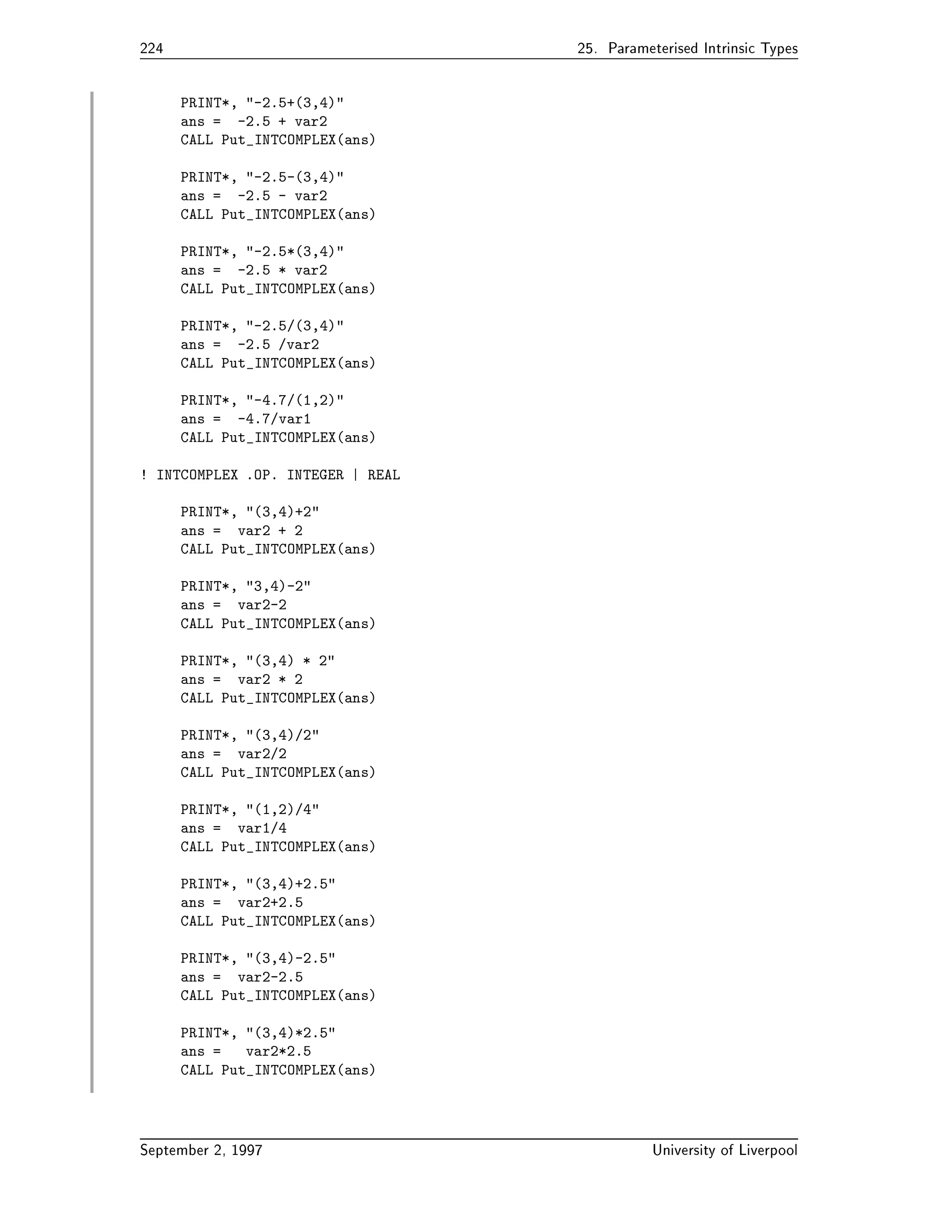

This document contains course notes for a Fortran programming course. It introduces basic computer science concepts like what a computer is, hardware and software, and how computer memory works. It then covers computer programs and programming, including an example temperature conversion program. It discusses programming languages, how to write programs, and common errors. It also provides an overview of the evolution of the Fortran programming language and its object oriented features.