This document provides guidelines for establishing UNESCO Green Academies across Africa and globally. It begins with background on population growth, natural resource and waste management issues in Africa. It then discusses the history and rationale behind UNESCO Green Academies. The functioning of Biosphere Reserves is also explained. The core of the guidelines focus on the five pillars of UNESCO Green Academies: rainwater utilization, wastewater recycling, production of clean energy, production of biomass, and establishing youth clubs. Case studies of existing green schools and academies are also presented. The document concludes with recommendations for recognizing UNESCO Green Academies.

![THEFIVEPILLARSOFUNESCOGREENACADEMIES

15

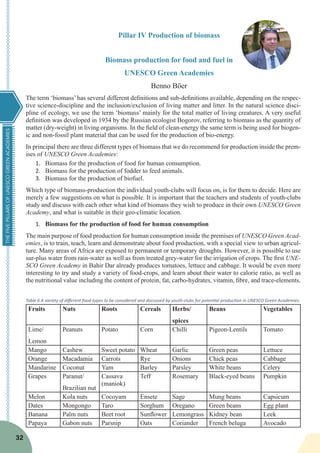

The RBM Logical ScoreCard

UNESCO Green Academy: Beza Bezuhan School, Lake Tana BSR

#

Results-Chains Performance Indicators /

Sources of Verification

Impacts (=Vision) By the end of the biennium, at least…

5

Students, teachers and community members (=

participants) in the Lake Tana BR enjoy the benefits

of practical environmental education (praceedu)1

;

thus building resilience and combating climate

change vulnerability.

VPI-1: 25% of the participants confirm that

they are enjoying the benefits of praceedu

and UNESCO is acknowledged.

Outcomes (= Mission) On an annual basis, at least….

4

Students, teachers and community members in the

Lake Tana BR use UNESCO facilitated praceedu;

including water from rainwater harvesting, recycled

grey water and renewable energy.

MPI-1: 50% water for gardens from RWH;

MPI-2: 50% fuel in school kitchen is bio-

gas;

MPI-3: 50% re-cycled water in bathrooms;

MPI-4: 02 Construction / maintenance jobs.

Outputs (= Deliverables) Produced by...

3

Out-1: [Hardware]: Infrastructure for rain water

harvesting (RWH), biogas production, and water re-

cycling in place, and their correct use promoted.

PI1-1:100,000-litres water by March 2016;

PI1-2: Biogas digester by March 2016;

PI1-3: Greywater recycling by July2016.

Out-2: [Software]: Guidelines for/in praceedu are

produced (or their production facilitated) and their

correct use actively promoted. PI2-1: Relevant guidelines in place by De-

cember 2016.

Out-3: [Human ware]: Students, teachers and

community members (= participants) in the Lake

Tana BSR trained in/for praceedu and supported

to apply their improved knowledge and skills.

PI3-1: At least 200 students, staff and com-

munity members trained by July 2016.

Out-4: [Management]: UNESCO Green Academy

project in the Lake Tana BSR is efficiently and ef-

fectively managed.

PI4-1: Project is managed within approved

budgets and plans.

Activities

2

Act-1: [Hardware]: Facilitate or design and build appropriate facilities for/in praceedu.

Act-2: [Software]: Develop new/updated guidelines for/in praceedu.

Act-3: [Human-ware]: Provide appropriate education and training programmes in praceedu.

Act-4: [Management]: Undertake planning, fund raising; implementation, M&E, and report-

ing.

Inputs / Resources

1

· Facilities and materials;

· Funding from Regular Programme and Extra-budgetary sources; and procedures and

methods;

· Knowledge and skills of UNESCO staff and partners.

Table 3 UNESCO Green Academies Logical ScoreCard](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e34633f-fccd-4f89-8106-811f0e2d64c1-161219153014/85/UNESCO-20Green-20Academies-20e-book-20compressed-20version-28-320.jpg)

![75

References

· African Development Bank [Internet], http://www.afdb.org/en/ [cited 20 October 2016]

· Amanuel, The Dramatic History of Addis Ababa Part 12: Background to Ethiopian Capitals, Capital Ethi-

opia, [Internet], 27 May 2013 http://capitalethiopia.com/2013/05/27/the-dramatic-history-of-addis-aba-

ba-part-12-background-to-ethiopian-capitals/#.V80h3LBf0b4 [cited 20th October 2016]

· Burt M., New ideas for rainwater harvesting at home, Tearfund international learning zone tilz.tearfund [Inter-

net] http://tilz.tearfund.org/en/resources/publications/footsteps/footsteps_81-90/footsteps_82/new_ideas_for_

rainwater_harvesting_at_home/ [cited 31 October 2016]

· Climate Data, [Internet], Climate: Jijiga http://en.climate-data.org/location/3651/ [cited 31 October 2016]

· Community Tool Box [Internet], Section 9. Establishing Youth Organizations, http://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-con-

tents/implement/provide-information-enhance-skills/youth-organizations/main [cited 15 September October

2016]

· Connect, UNESCO International Science, Technology & Environmental Education Newsletter, Vol XX-

VII No 1-2: 1-4. Environmental education: possibilities and constraints. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/imag-

es/0014/001462/146295e.pdf [cited 15 September October 2016]

· Cowan C. The Greenest School on Earth: How do you choose?, US Green Building Council [Internet], 25th

April 2015 http://www.usgbc.org/articles/greenest-school-earth-how-do-you-choose [cited 31st October 2016]

· Davis S., How much water is enough? Determining realistic water use in developing countries, Improve In-

ternational [Internet], 27th

April 2014, https://improveinternational.wordpress.com/2014/04/27/how-much-wa-

ter-is-enough-determining-realistic-water-use-in-developing-countries/ [cited 31 October 2016]

· Dennehy E., D. D’Ambrosio & C.Tam, 2015, Tracking Clean Energy Progress, International Energy Agency,

IEA, 98 pp.

· Department of Energy and Climate Change UK, 2014, Power to the pupils Solar PV for schools – The benefits.

UK Government. 6 pp.

· Eco-school programs [Internet], Become an eco-school http://www.nwf.org/Eco-Schools-USA/Become-an-

Eco-School.aspx [cited 21 October 2016]

· European Union ECO-SCHOOLSprogram [Internet], http://www.welcomeurope.com/european-funds/eco-

schools-417+317.html#tab=onglet_details [cited 21st October 2016]

· FAO Youth and United Nations GlobalAlliance (YUNGA) [Internet], http://www.fao.org/yunga/home/en/ [cited

15 September 2016]

· FAO [Internet] Biodiversity Challenge Badge, http://www.fao.org/3/a-i1885e.pdf [cited 15 September 2016]

· Water Challenge Badge, http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3225e.pdf

· Forests Challenge Badge, http://www.fao.org/docrep/018/i3479e/i3479e.pdf

· Ending Hunger Challenge Badge, http://www.fao.org/docrep/018/i3466e/i3466e.pdf

· Food security and climate challenge badge, http://www.fao.org/3/a-i1091e.pdf

· Soils Challenge Badge, http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3855e.pdf

· Youth Guide to Biodiversity, (http://www.fao.org/docrep/017/i3157e/i3157e00.htm)

· Youth Guide to Forests, http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3856e.pdf

· Climate Change, www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/fao_ilo/pdf/Other_docs/FAO/Climate_Change.pdf

· Community Seed Banks, www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/fao_ilo/pdf/Other_docs/FAO/Community_Seed_

Banks.pdf

· Aquaculture, www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/fao_ilo/pdf/Other_docs/FAO/Aquaculture.pdf](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e34633f-fccd-4f89-8106-811f0e2d64c1-161219153014/85/UNESCO-20Green-20Academies-20e-book-20compressed-20version-88-320.jpg)

![76

· Junior Farmer Field and Life School Inventory, http://www.fao.org/3/a-ak595e.pdf

· Junior Farmer Field and Life experiences, challenges and innovation ftp://ftp.fao.org/docrep/fao/011/i0379e/

i0379e.pdf

· Farewell architects [Internet], Health wellness nutrition centre the willow school, http://www.farewell-archi-

tects.com/health-wellness-nutrition-center-the-willow-school-1/ [cited 31 October 2016]

· Ferroukhi R., A. Khalid, M. Renner & Á. López-Peña, 2016, Renewable Energy and Jobs Annual Review

2016. IRENA. 20 pp.

· Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2010, Global forest resources assessment 2010. 378

pp.

· Galluzzo T. & D. Osterberg, 2006, Wind power and Iowa schools. The Iowa Policy Project. 40 pp.

· Gsänger S. & J. D. Pitteloud, 2012, The World Wind Energy Association

· Green Schools Ireland [Internet], http://greenschoolsireland.org/ [cited 21 October 2016]

· Hina Fathima.A, Priya. K, Sudakar Babu.T, Devabalaji.K.R, Rekha.M, Rajalakshmi.K & Shilaja.C, 2014, Prob-

lems in Conventional Energy Sources and Subsequent shift to Green Energy. School of Electrical Engineering,

VIT University, Vellore, India. 7 pp.

· Hook T., K. Kardos, A. Lao, S. Vasudevan, E. Wall, 2016, PEERs for Peace guide. UNESCO IICBA, 122 pp.

http://www.iicba.unesco.org/sites/default/files/sites/default/files/Peers4Peace_Final_21Sept2016.pdf [cited 12-

10-2016]

· International Labour Office ILO, 2014, Global Employment Trends 2014: Risk of a jobless recovery. 120 pp.

· Jordan Green Building Council Website [Internet], www.jordangbc.org/ [cited 20 October 2016]

· Karkara R. & R. Porhukuchi [Internet], Youth Perspective: Youth Action Guide on the SDGs, Sustainability

Thomsonreuters, 5 February 2016,

http://sustainability.thomsonreuters.com/2016/02/05/youth-perspective-youth-action-guide-on-the-sdgs/ [cited

15 September 2016]

· Kaye J. L., D. Jensen, J. Clover, S. Lonergan, M. Levy, B. Bowling, B. Bromwich, S. Halle, N. Barefoot, D.

Hamro-Drotz, B. Mourad, R. Sexton, 2012, Renewable resources and conflict. UNEP. 119 pp.

· Lowe S., Browne M., Boudjelas S., De Poorted M., 2000, 100 of the World’s Worst Invasive Alien Species A se-

lection from the Global Invasive Species Database. Pubblished y The Invasice Species Specialist Group (ISSG)

a specialist group of the Species Survival Commission (SSC) of the World Conservation Union (IUCN), 12 pp.

· McCrone A., U. Moslener, F. d’Estais, E. Usher, C. Grüning, 2016, Global Trends in Renewable Energy In-

vestment 2016. UNEP’s Division of Technology, Industry and Economic (DTIE) in cooperation with Frankfurt

School-UNEP Collaborating Centre for Climate & Sustainable Energy Finance. 84 pp.

· National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration [Internet] http://www.noaa.gov/ [cited 20 October]

· Next Gen Climate, 2015, The economic case for clean Energy. 17 pp.

· Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD, and United Nations, Department of Eco-

nomic and Social Affairs, UN-DESA, 2013, World Migration in Figures. 6 pp.

· Pachamama Alliance [Internet], Environmental Awareness, https://www.pachamama.org/environmental-aware-

ness, [cited 14 October 2016]

· Pachamama Alliance [Internet], Awakening the Dreamer (2-Hour free Online Course), http://engage.pachama-

ma.org/awakening-the-dreamer-5/?_ga=1.143586934.255418166.1422278843 [cited 15 September 2016]

· Pavlicek P., V. Mouchkin, Chernobyl: The True Scale of the Accident, 20 April 2006, online video clip Inter-

national Atomic Energy Agency IAEA website, https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/multimedia/videos/cher-

nobyl-true-scale-accident [cited 14 October 2016]

· Ryan P.A. The Use of Tree Legumes for Fuelwood Production, Food and Agriculture Organization of the Unit-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e34633f-fccd-4f89-8106-811f0e2d64c1-161219153014/85/UNESCO-20Green-20Academies-20e-book-20compressed-20version-89-320.jpg)

![77

ed Nations, [Internet], http://www.fao.org/ag/agp/agpc/doc/publicat/gutt-shel/x5556e0p.htm [cited 20 October

2016]

· Schwarze, H., M. Breulmann, M. Sutcliffe, B. Böer, D. Al-Eisawi, N. Al-Hashimi, K. Batanouny, J, Böcker, P.

Bridgewater, G.Brown, A. Bubtana, G. Faulstich, R. Loughland, N. Es’Haqi, P. Neuschäfer, M. Richtzenhain,

K. Scholz-Barth, S. Chaudhary & F. Techel, 2010, Better Buildings. Enhanced water-, energy- and waste-man-

agement in Arab urban ecosystems – globally applicable. UNESCO, Friends of the Environment Centre, UNEP

& UNIC. 44p.

· Sauvè L. 2002, Environmental Education: Possibilities and Constraints

· Scientific American [Internet], How to Start an Environmental Club at Your School http://www.scientificameri-

can.com/article/how-to-start-an-environment-club/ [cited 15 September 2016]

· Small farm permaculture and sustainable living, [Internet], http://www.small-farm-permaculture-and-sustain-

able-living.com/what_do_chickens_eat.html [cited 14 October 2016]

· The Club of Rome Limits to Growth http://www.clubofrome.org/eng/home/ [cited 15 September 2016]

· The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited, 2016, Power Up: Delivering renewable energy in Africa

· The Guardian Ban Ki-moon: why partnerships are key to fulfilling millennium goals https://www.theguardian.

com/media-network/media-network-blog/2013/nov/15/ban-ki-moon-millennium-development [cited 27 October

2016]

· UK Government [Internet], Fuel Substitution – Poverty Impacts on Biomass Fuel Suppliers. Country Status

Report Ethiopia, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08d17e5274a31e0001638/R8019Annex-

1Ethiopia.pdf [cited 20 October 2016]

· UNEP/UNESCO, 2016 (Soon to be released) YouthXchange Training Kit on Responsible Consumption for Af-

rica

· UNESCO [Internet], Teaching and Learning for a Sustainable Future http://www.unesco.org/education/tlsf/

[cited 15 September 2016]

· UNESCO [Internet], 2009 Clubs for UNESCO: a practical guide, http://unesdoc.unesco.org/imag-

es/0018/001821/182131e.pdf [cited 15 September 2016]

· UNESCO, 1996, Practical guide for the development of instructional materials for EPD in Africa South of the

Sahara

· UNESCO [Internet], Environmental education activities for primary schools: suggestions for making and using

low cost equipment, http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0009/000963/096345eo.pdf [cited 15 September 2016]

· UNESCO [Internet], Guide on simulation and gaming for environmental education, http://unesdoc.unesco.org/

images/0005/000569/056905eo.pdf [cited 15 September 2016]

· UNESCO [Internet], Biological diversity for secondary education: environmental education module, http://un-

esdoc.unesco.org/images/0011/001113/111306eo.pdf, [cited 15 September 2016]

· UNESCO [Internet], The Teacher’s handbook: using the local environment, http://unesdoc.unesco.org/imag-

es/0012/001230/123071eb.pdf, [cited 15 September 2016]

· UNESCO [Internet], YouthXchange Biodiversity & Lifestyles guidebook, http://unesdoc.unesco.org/imag-

es/0023/002338/233877e.pdf [cited 15 September 2016]

· UNESCO [Internet], YouthXchange: Green Skills and Lifestyles Guidebook, http://unesdoc.unesco.org/imag-

es/0024/002456/245646e.pdf [cited 15 September 2016]

· United Nations, [Internet], Sustainable Development Goals, http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sus-

tainable-development-goals/ [cited 13 October 2016]

· United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2014).

· WikiHowTo [Internet], How to Create an Environmental Club, http://www.wikihow.com/Create-an-Environ-

mental-Club [cited 15 September 2016]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e34633f-fccd-4f89-8106-811f0e2d64c1-161219153014/85/UNESCO-20Green-20Academies-20e-book-20compressed-20version-90-320.jpg)

![78

· Wikipedia [Internet], Renewable energy, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Renewable_energy [cited 9 October

2016]

· Wikipedia [Internet], Solar energy, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solar_energy [cited 14 October 2016]

· Wikipedia [Internet], List of waste type (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_waste_types) [cited 14th

October

2016]

· Wilson D. C., L. Rodic, P. Modak, R. Soos, A. C. Rogero, C. Velis, M. Iyer & O. Simonett, 2015, Global waste

management outlook. UNEP. 346 pp.

· Windustry [Internet], 2011, How much do wind turbines cost, http://www.windustry.org/how_much_do_wind_

turbines_cost [cited 14 October 2016]

· World Bank [Internet], Urban development (http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/TOPICS/EX-

TURBANDEVELOPMENT/0,,contentMDK:23172887~pagePK:210058~piPK:210062~theSitePK:337178,00.

html) [cited 14th

October 2016]

· World Urbanization Prospects: The 2014 Revision, Highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/352). 32 pp.

· World Wild Fund for Nature WWF - Pakistan Green School Certification [Internet], http://www.wwfpak.org/

greenschool/ [cited 21 October 2016]

· World Wild Fund for Nature WWF - Pakistan Green School Certification [Internet], Green School Programme

http://www.wwfpak.org/greenschool/pdf/BSSGreenSchoolReport2012-13-nr.pdf [cited 21 October 2016]

· Wright, C., Mannathoko, C., and Pasic, M. 2006. The child friendly school manual, 1–244. New York:

UNICEF. 244 pp. http://www.unicef.org/publications/files/Child_Friendly_Schools_Manual_EN_040809.pdf

[cited 14 October 2016]

· Wright, E. Alaphia, (2015), The Rule-of-3 in Results Based Performance Management, Reach Publishers,

Durban, 325 pp.

· You D., L. Hug & D. Anthony, 2014: Generation 2030 Africa – child demographics in Africa; United Nations

Children’s Fund UNICEF, Division of Data, Research, and Policy. 68 pp.

(Footnotes)

1 Praceedu = practical environmental education covering rainwater harvesting (RWH), waste water management and

the use of renewable energy, including biogas; Plus appropriate lessons and mentoring in the culture of peace.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e34633f-fccd-4f89-8106-811f0e2d64c1-161219153014/85/UNESCO-20Green-20Academies-20e-book-20compressed-20version-91-320.jpg)