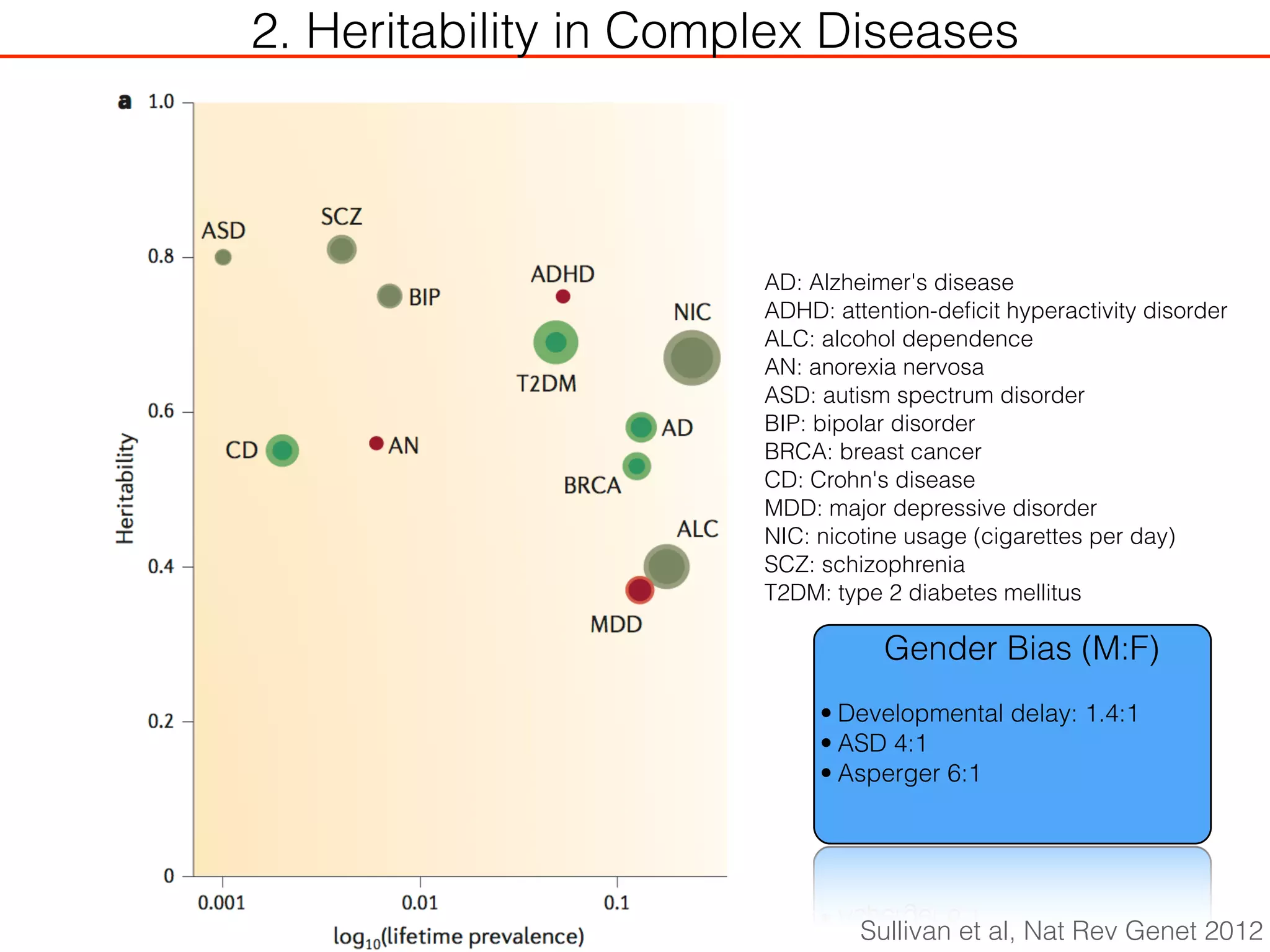

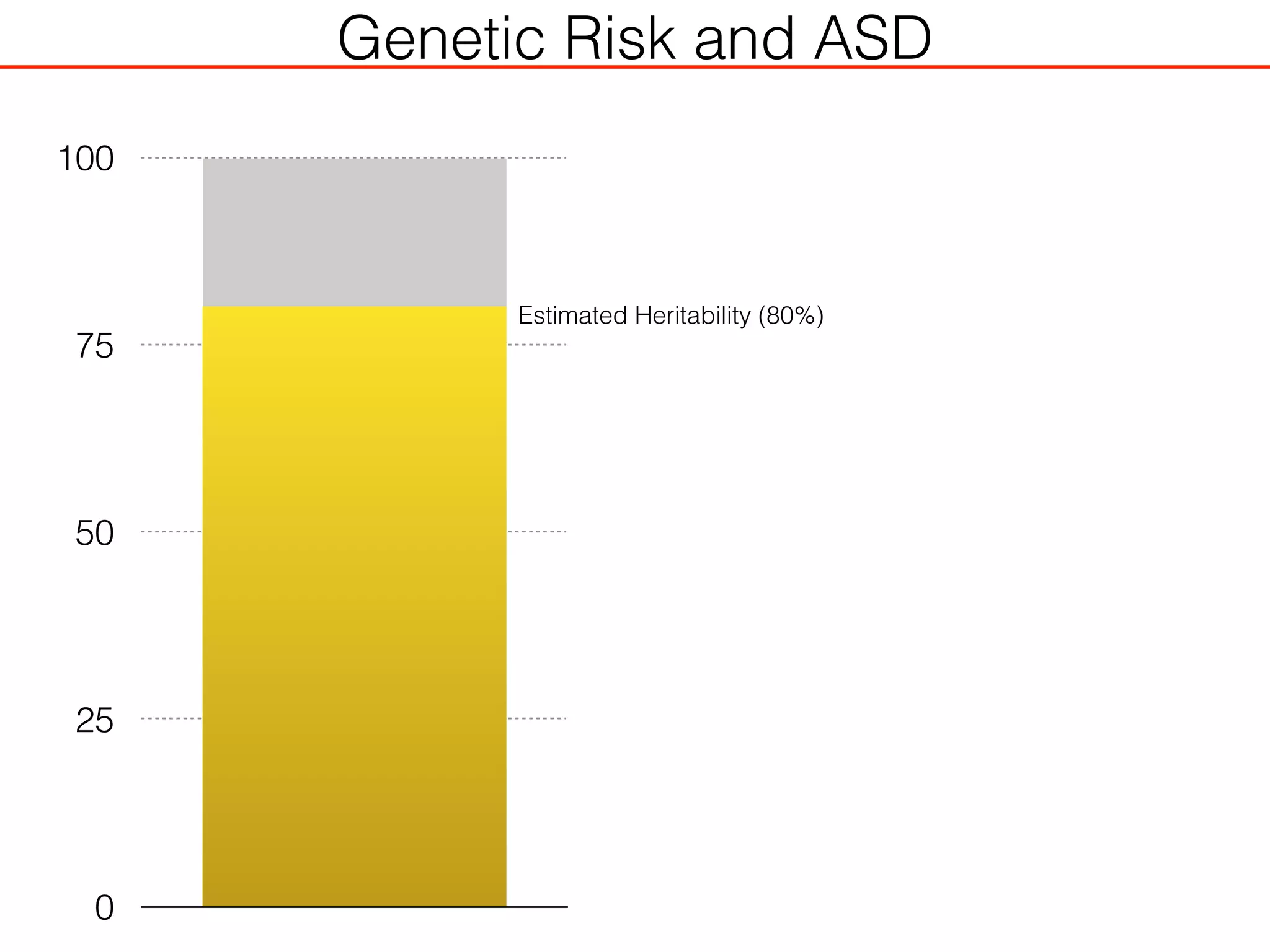

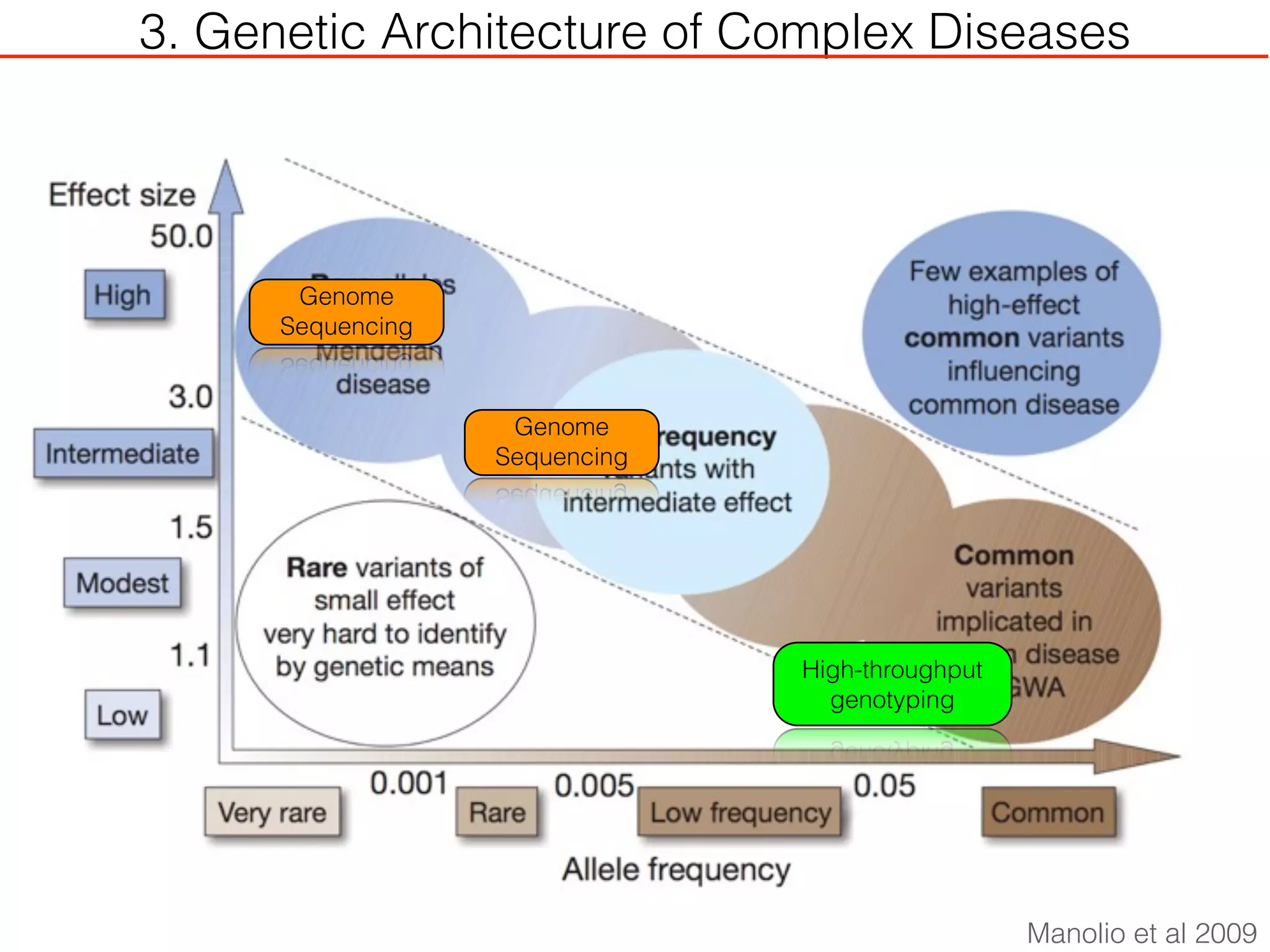

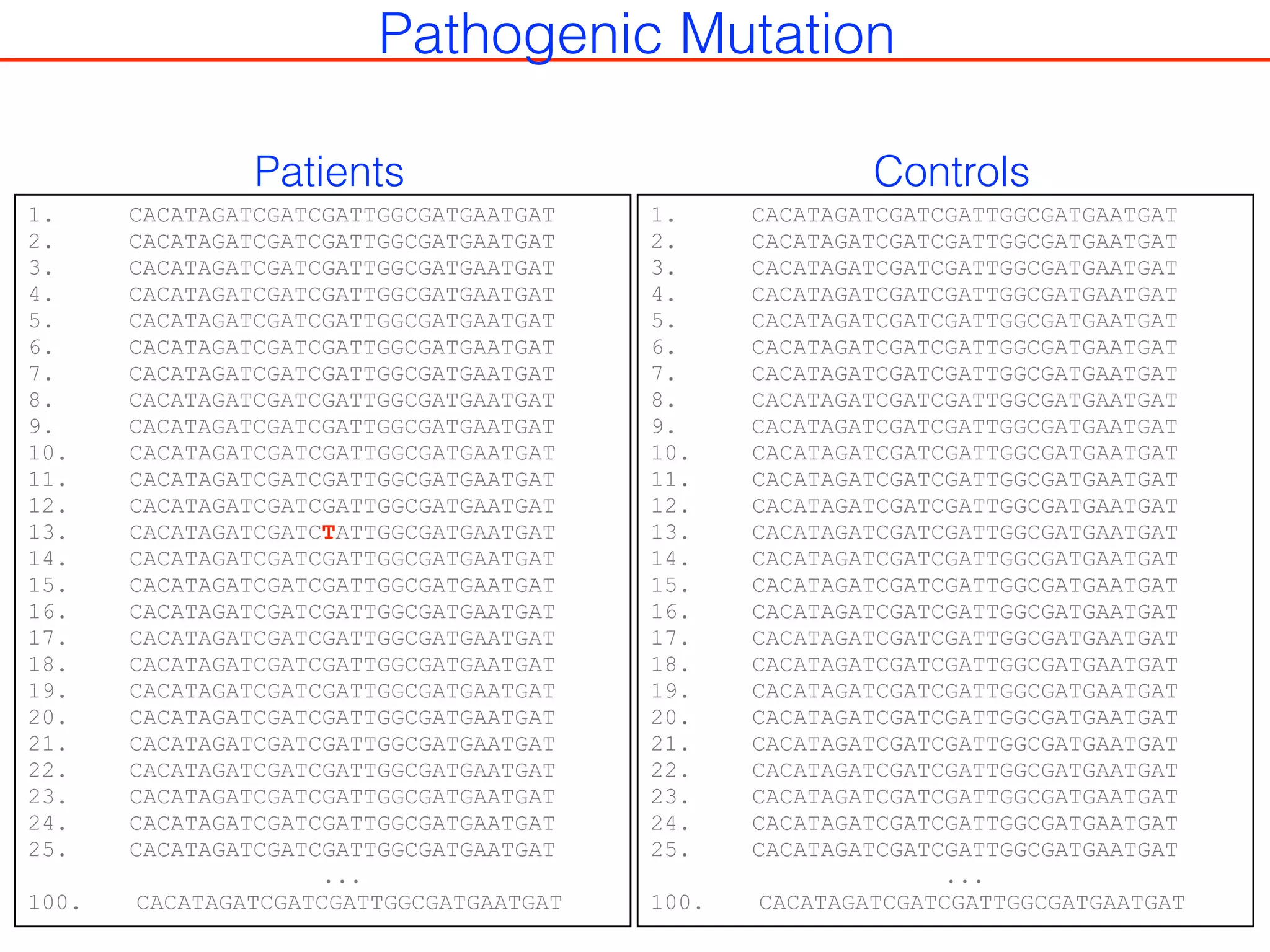

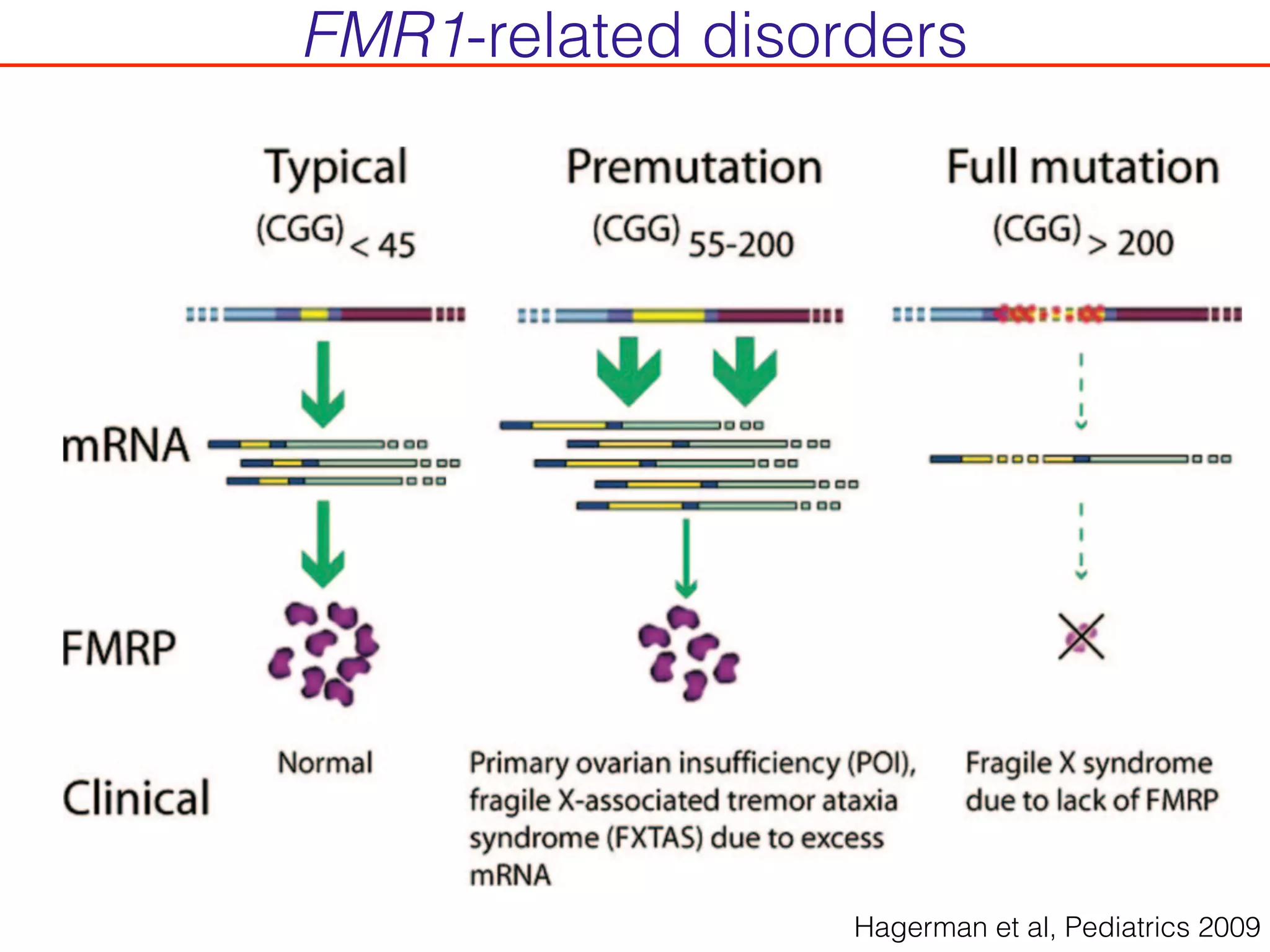

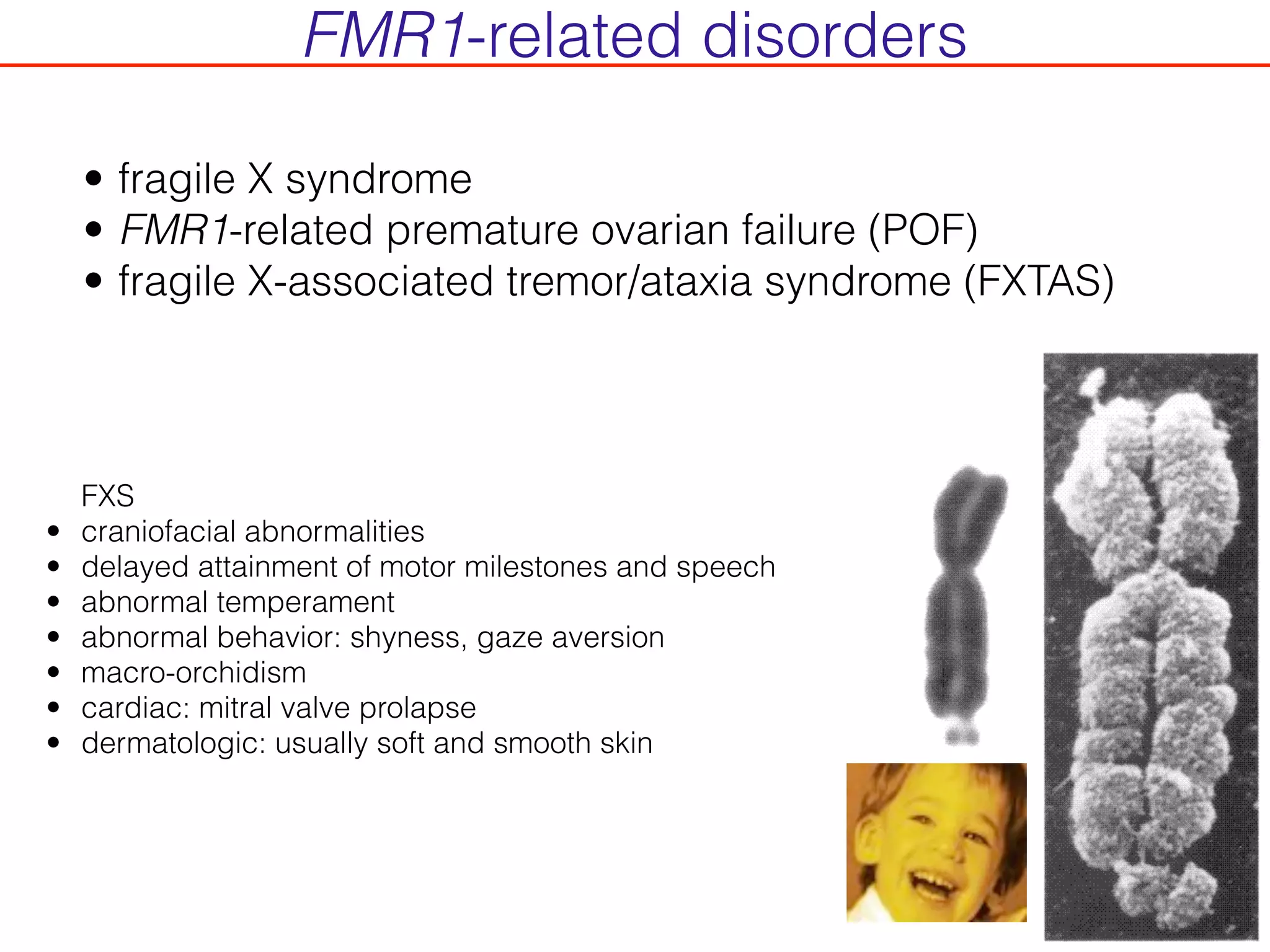

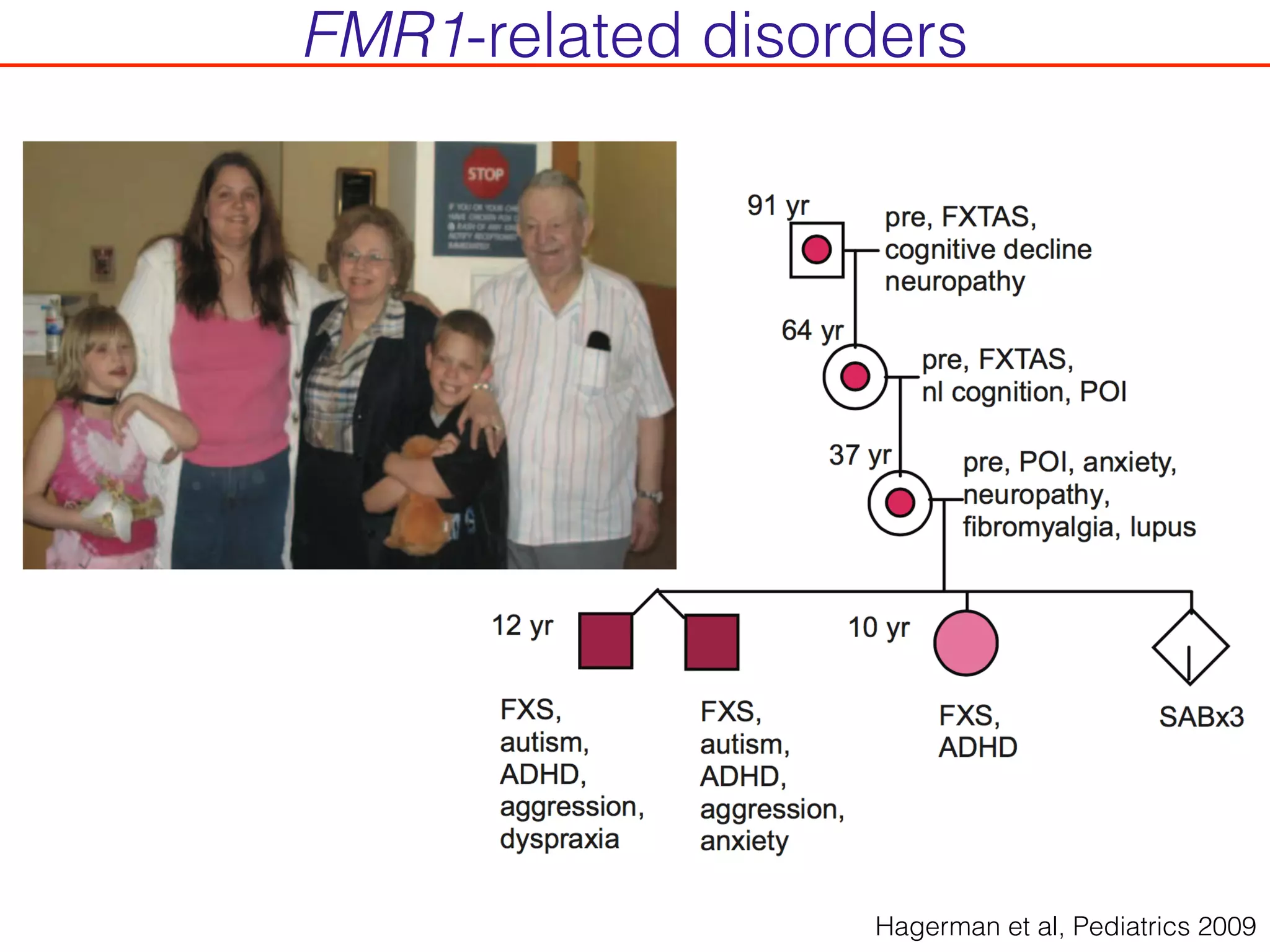

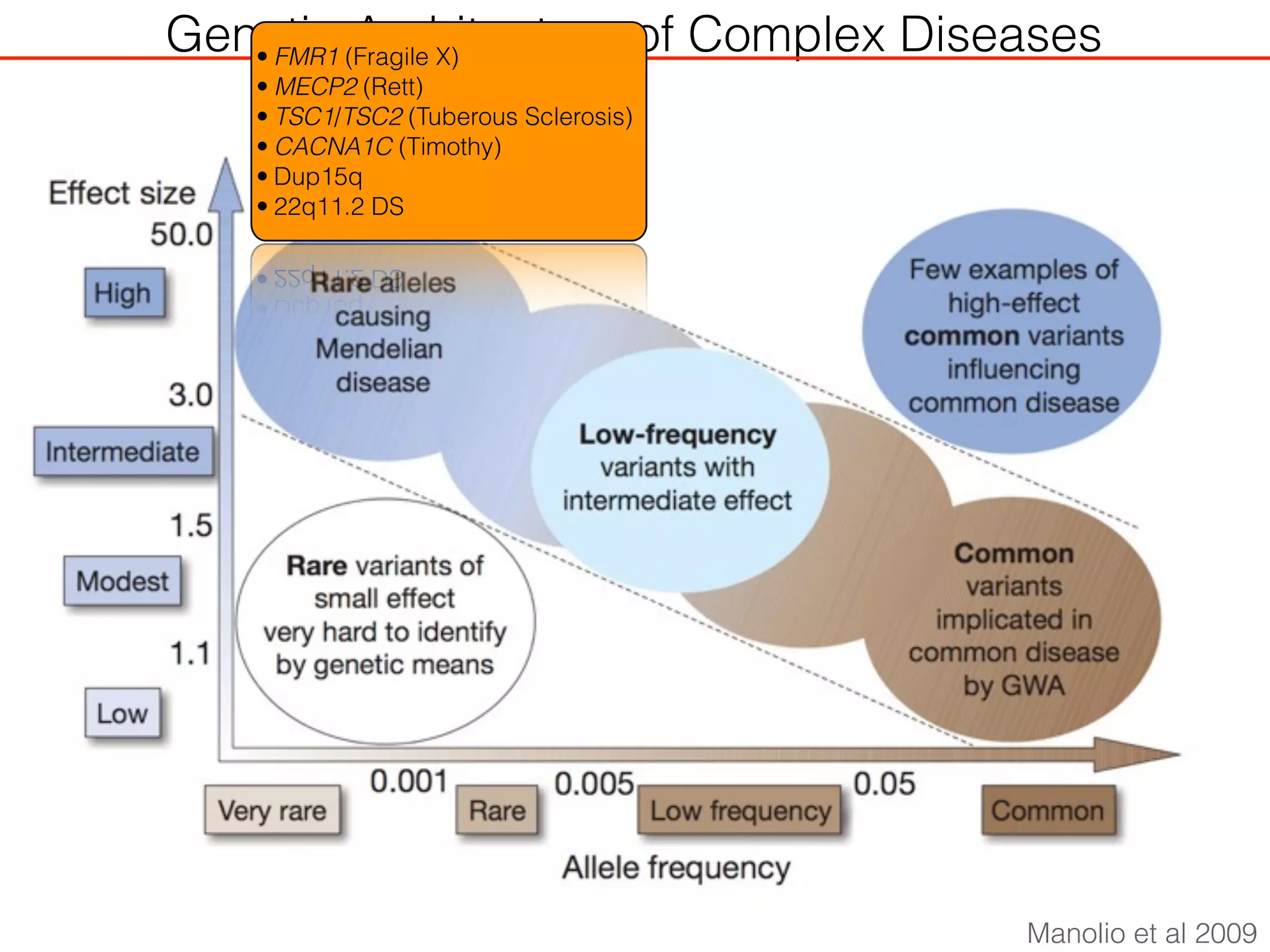

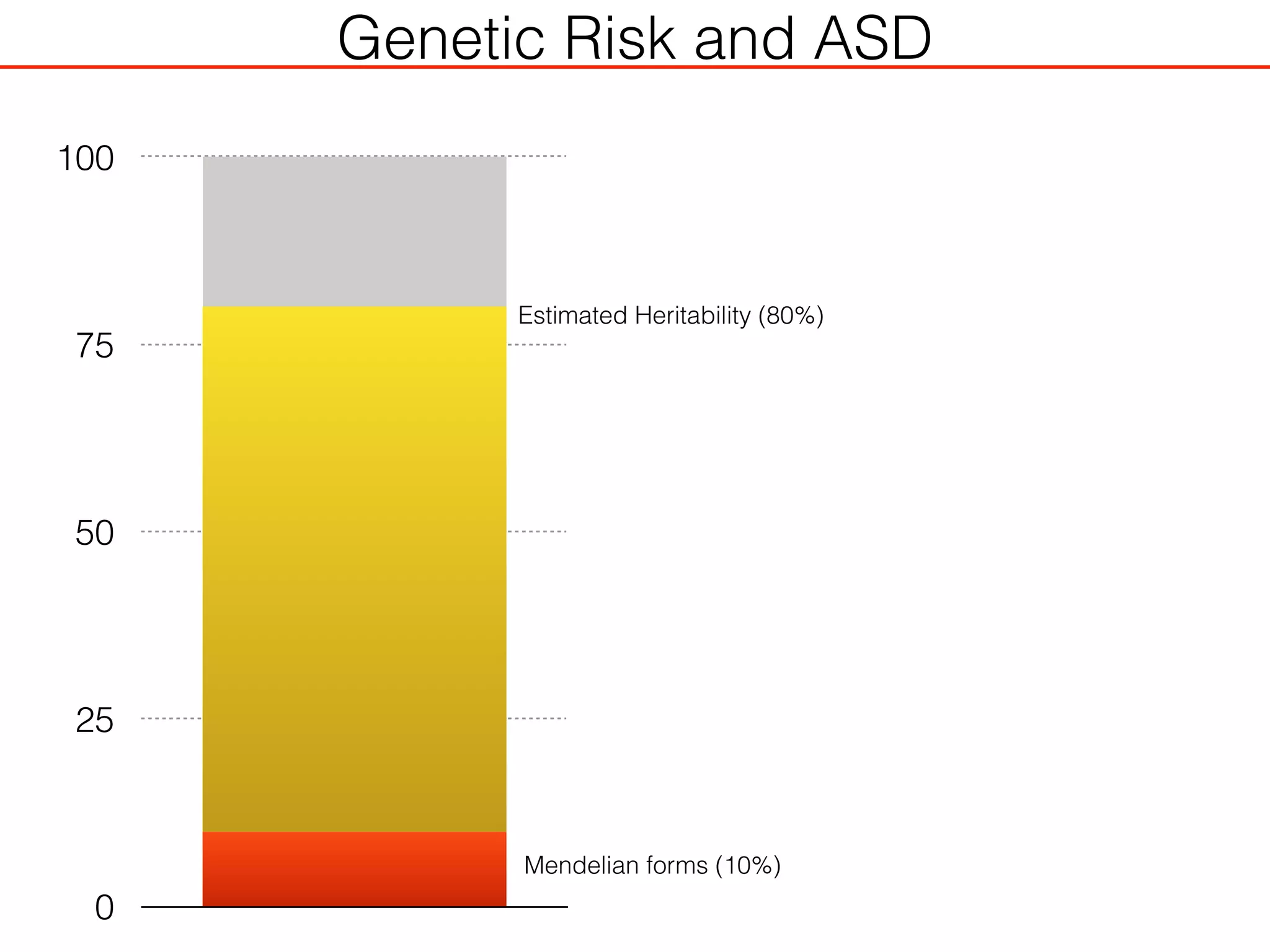

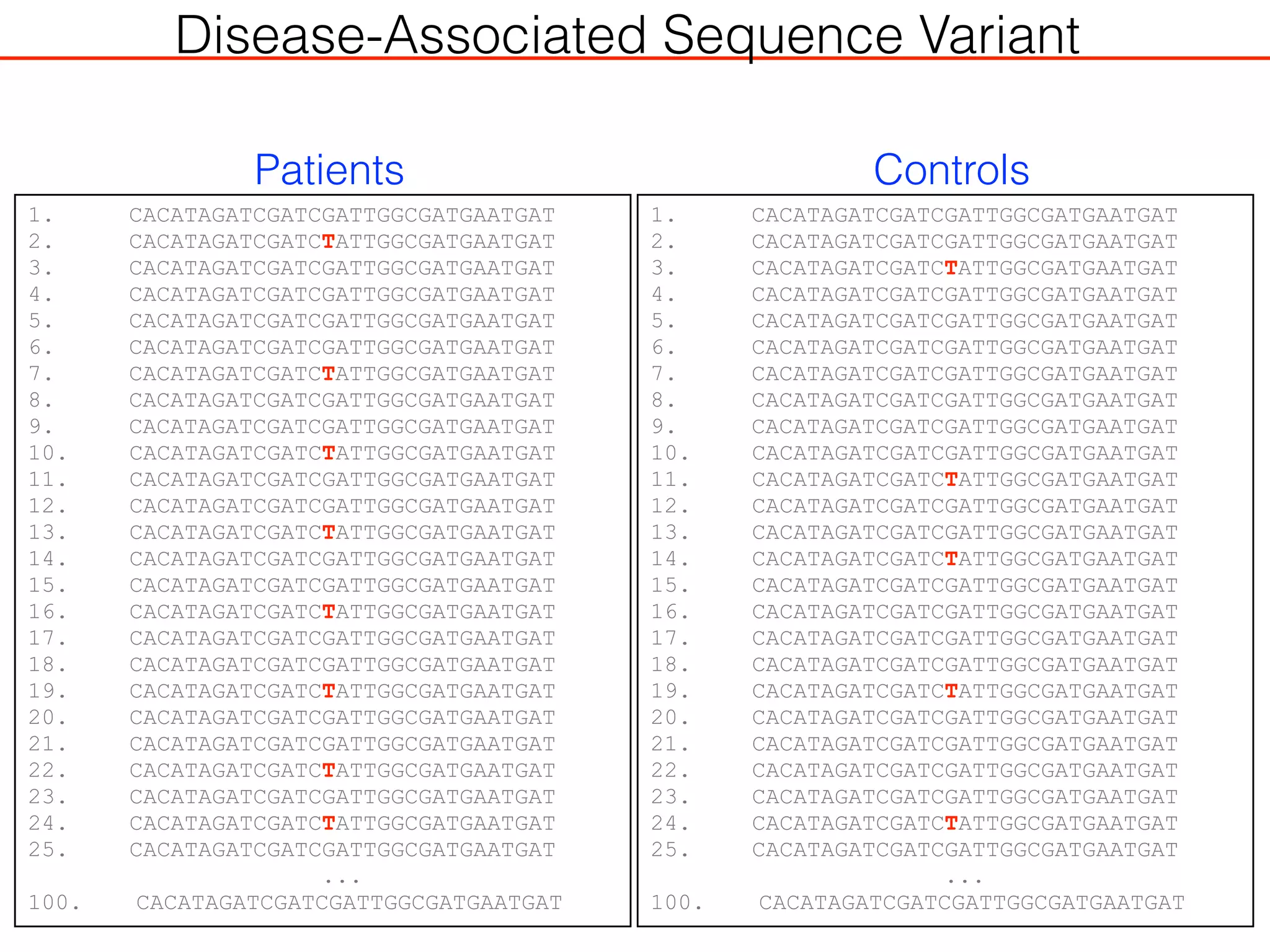

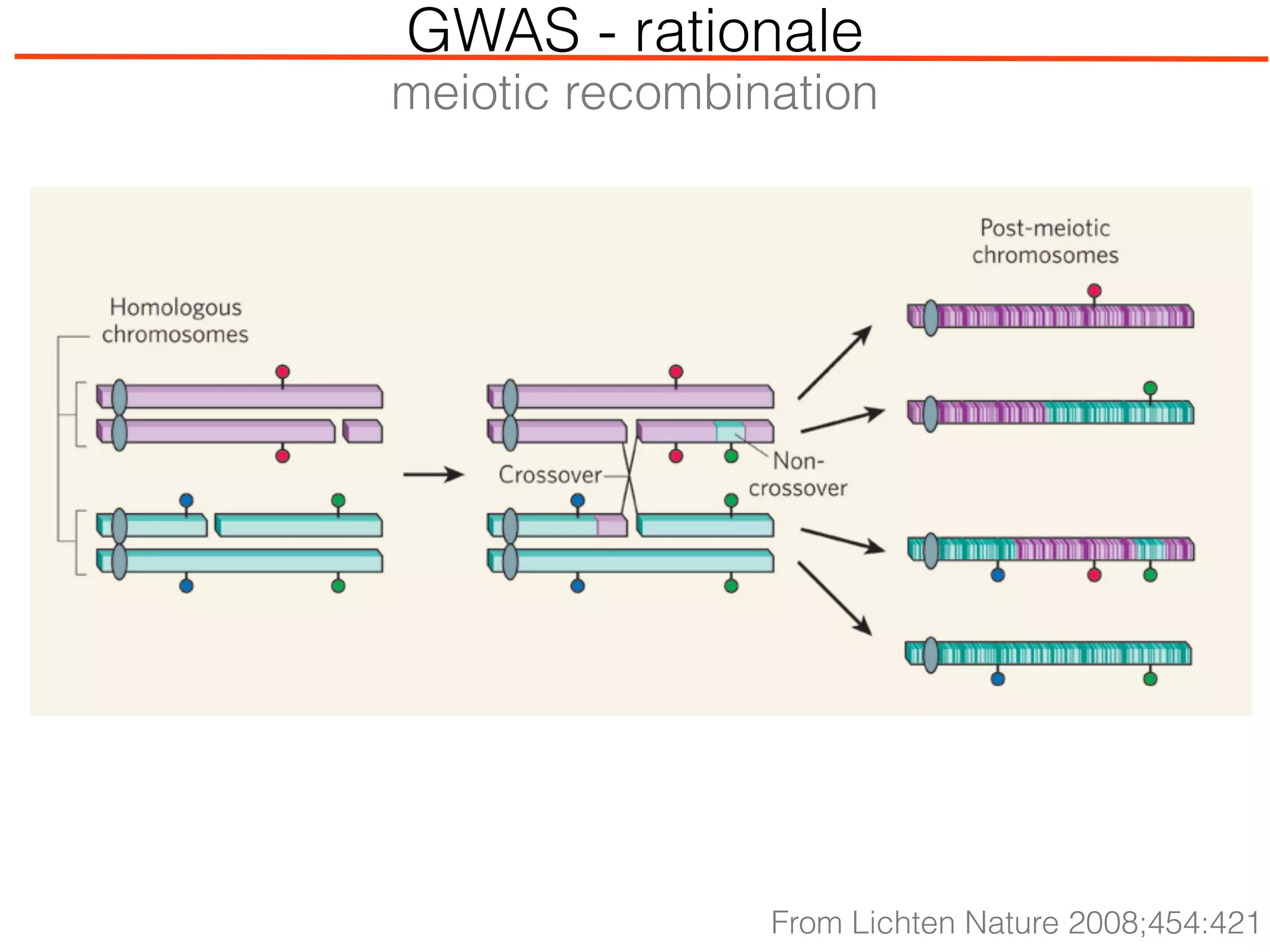

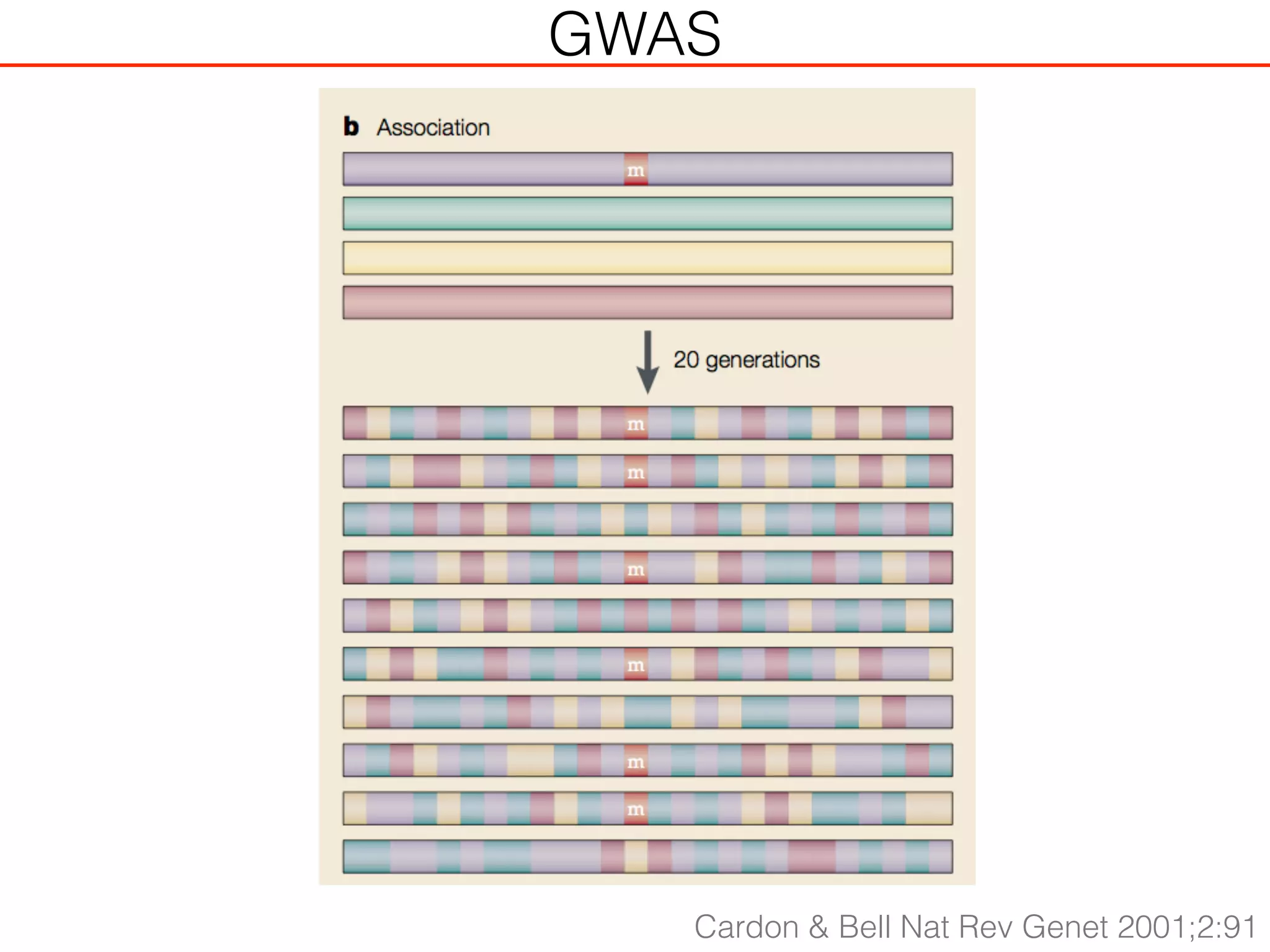

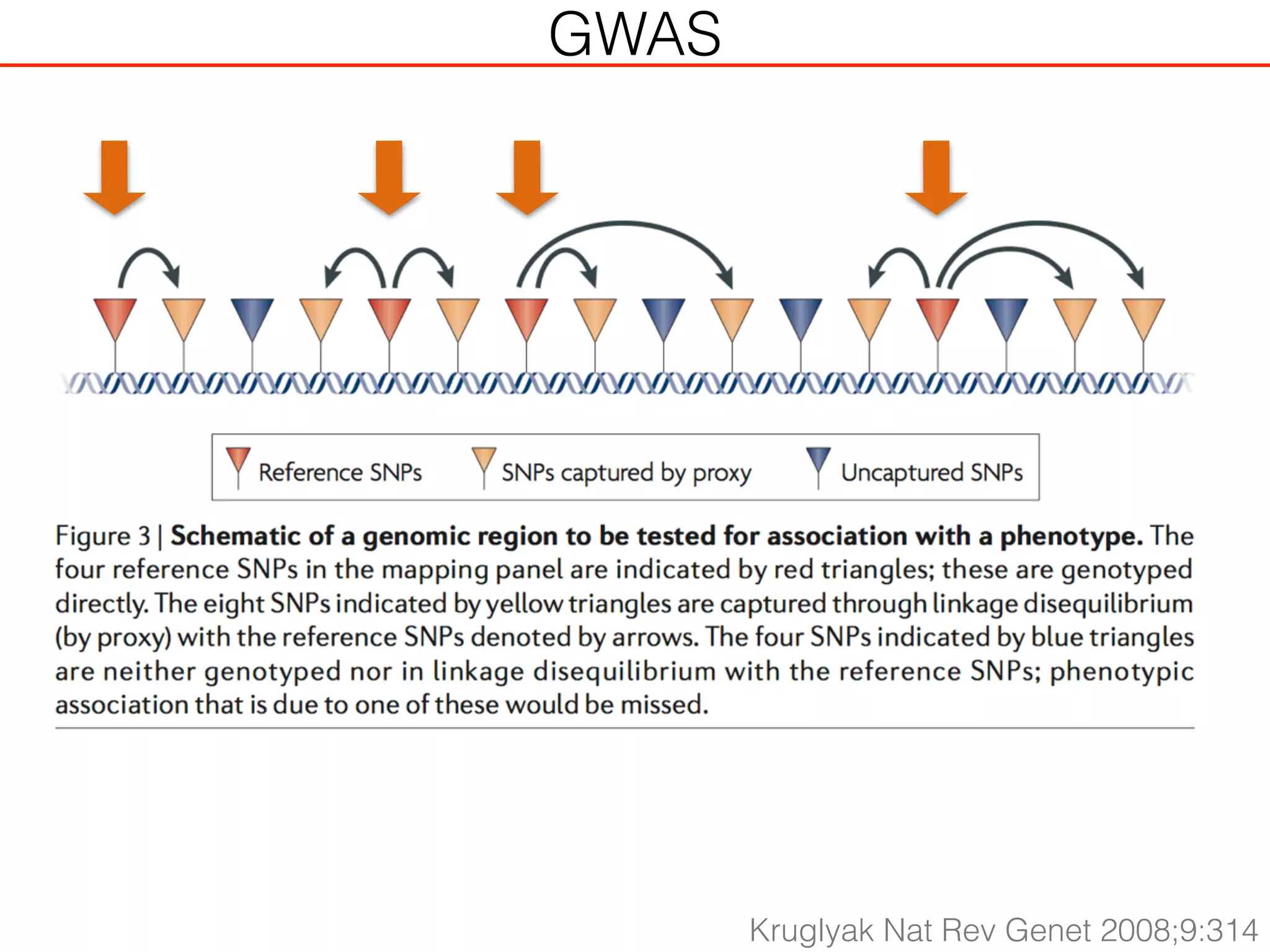

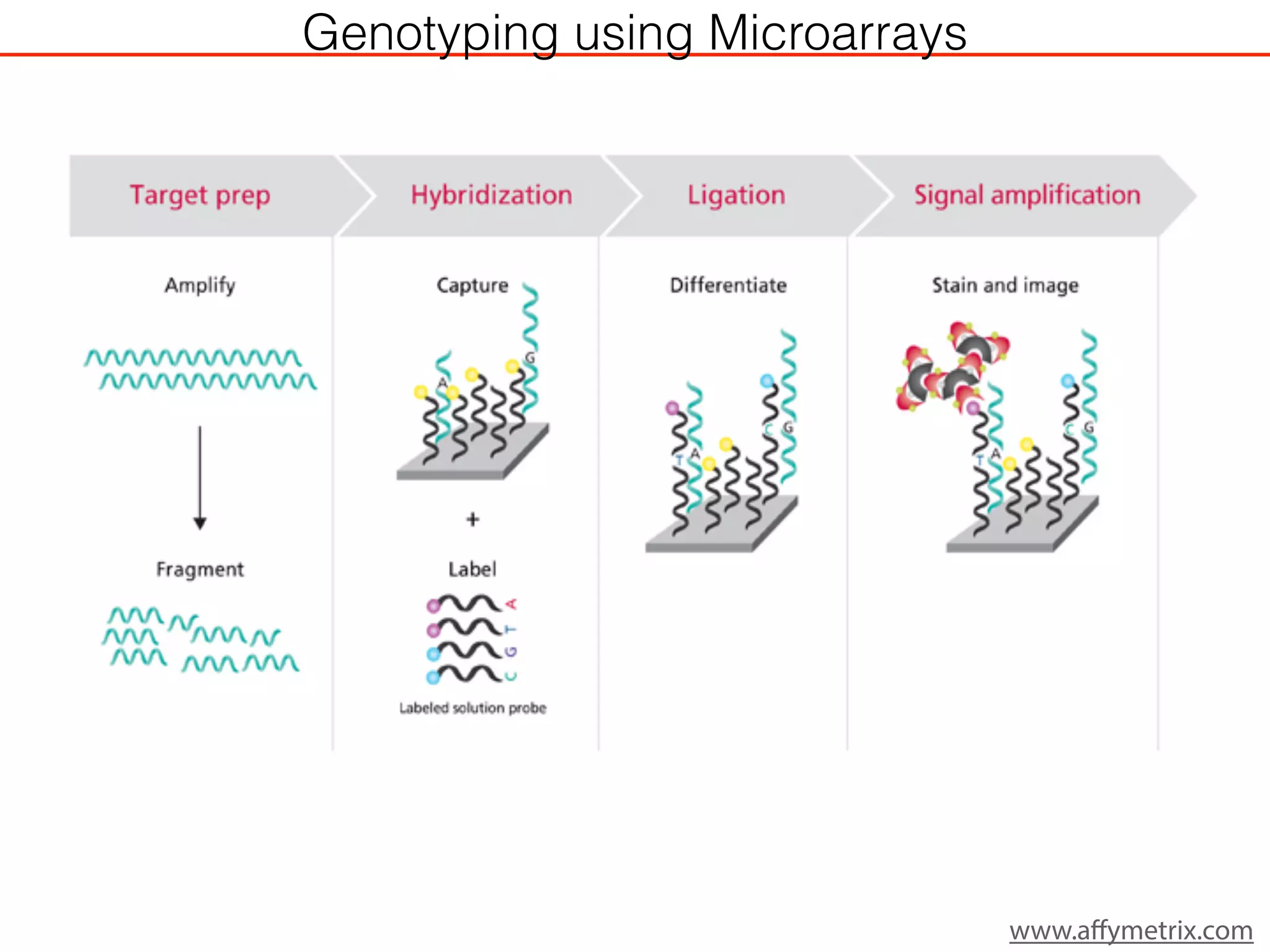

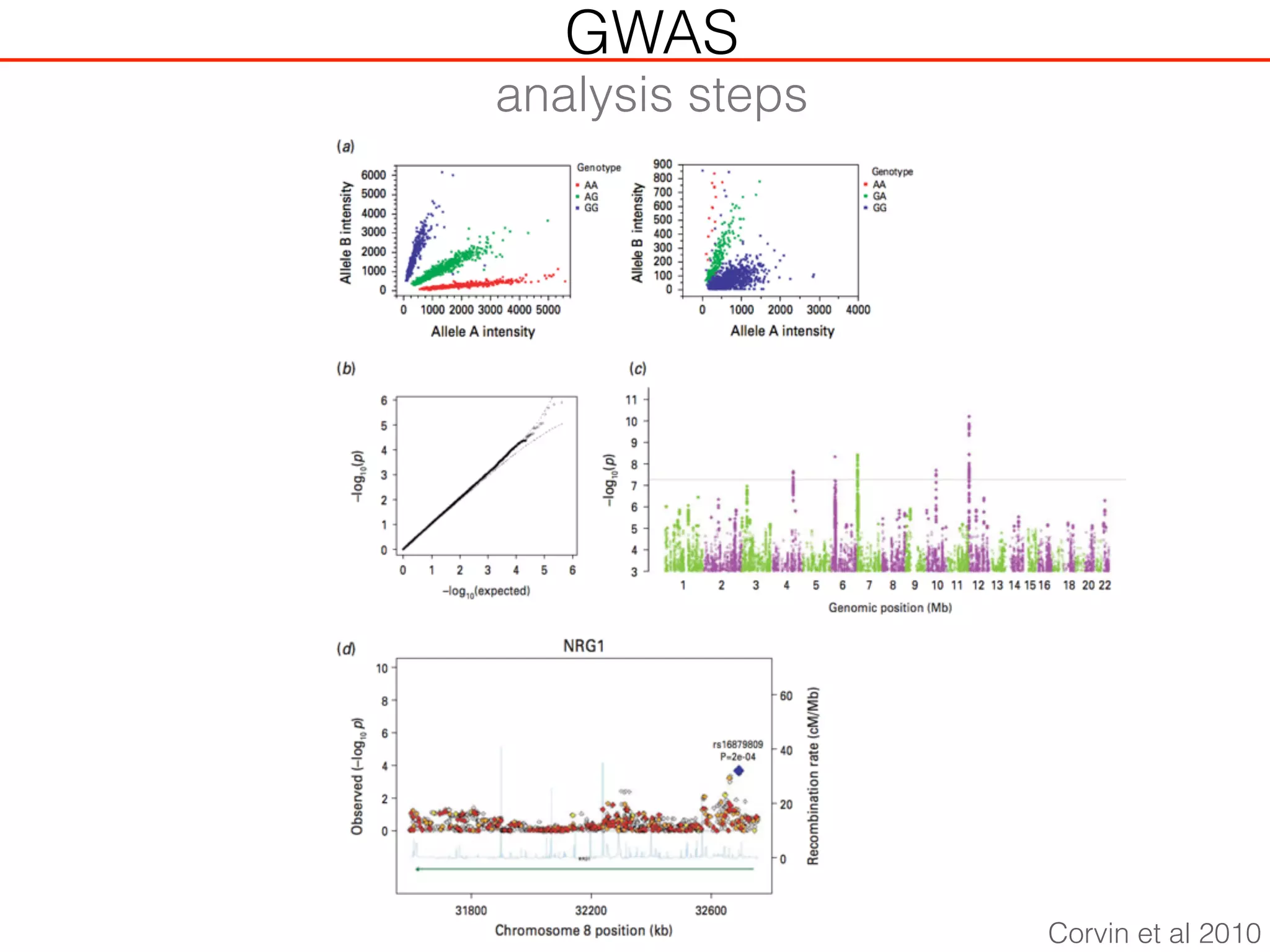

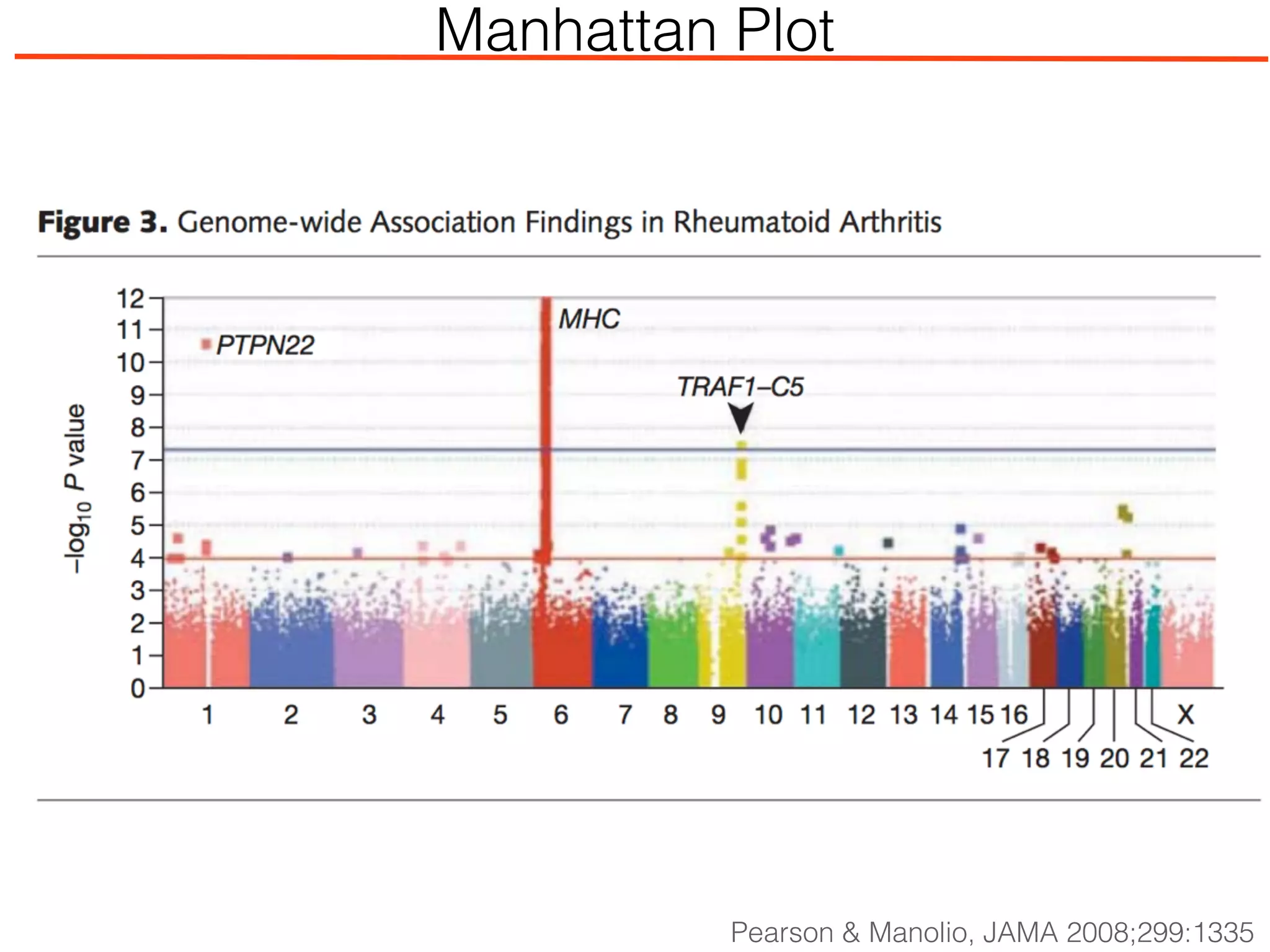

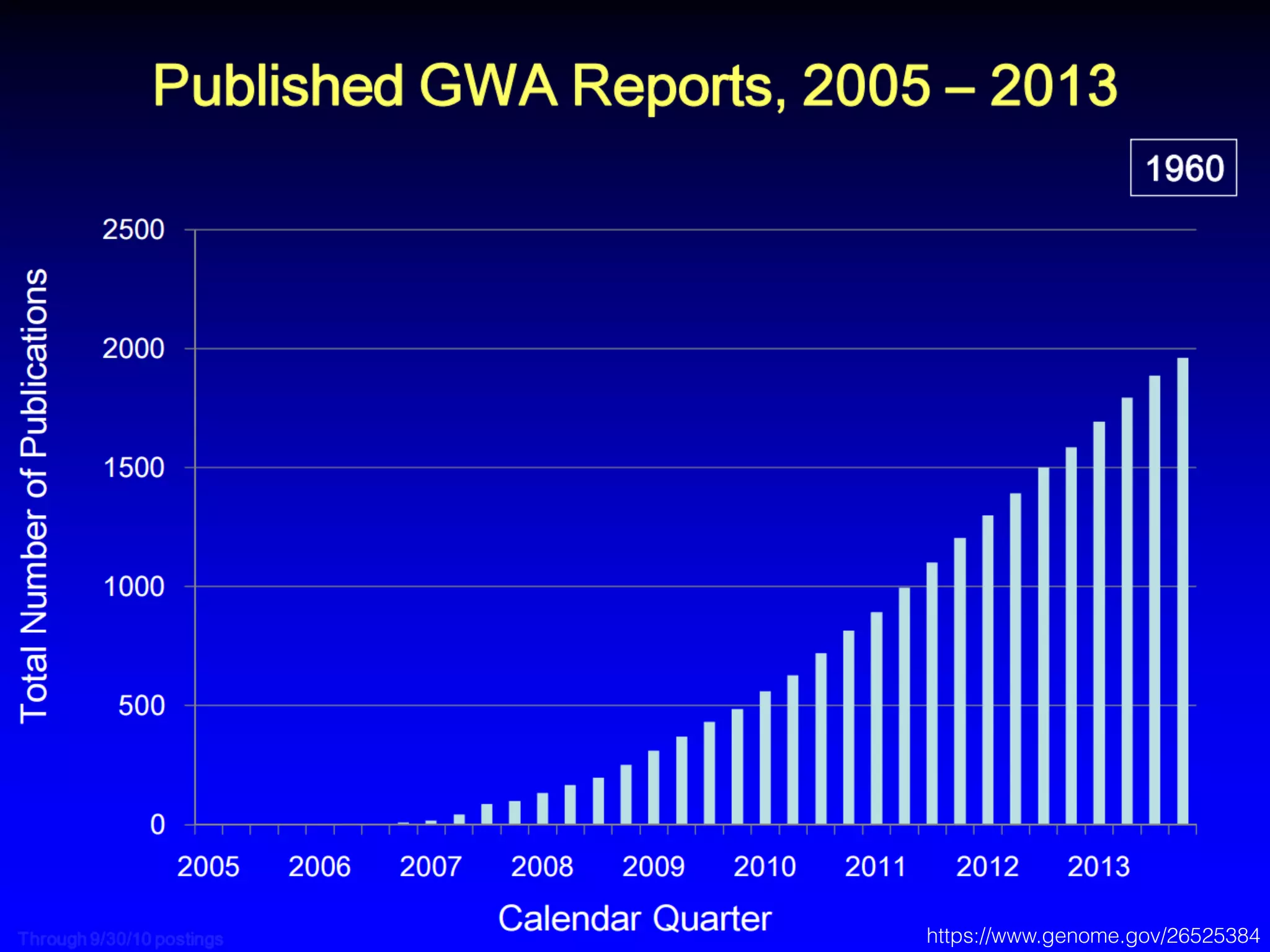

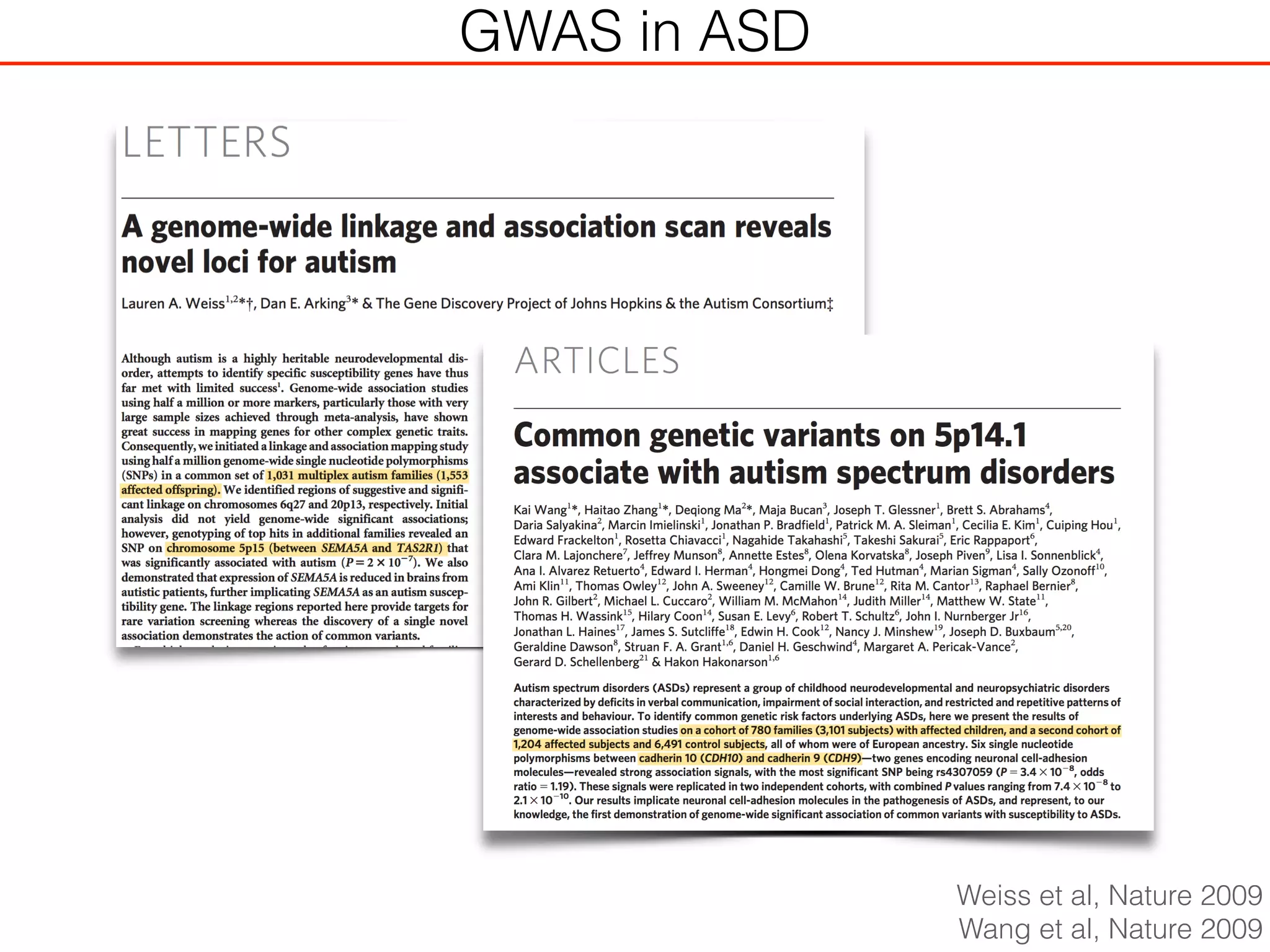

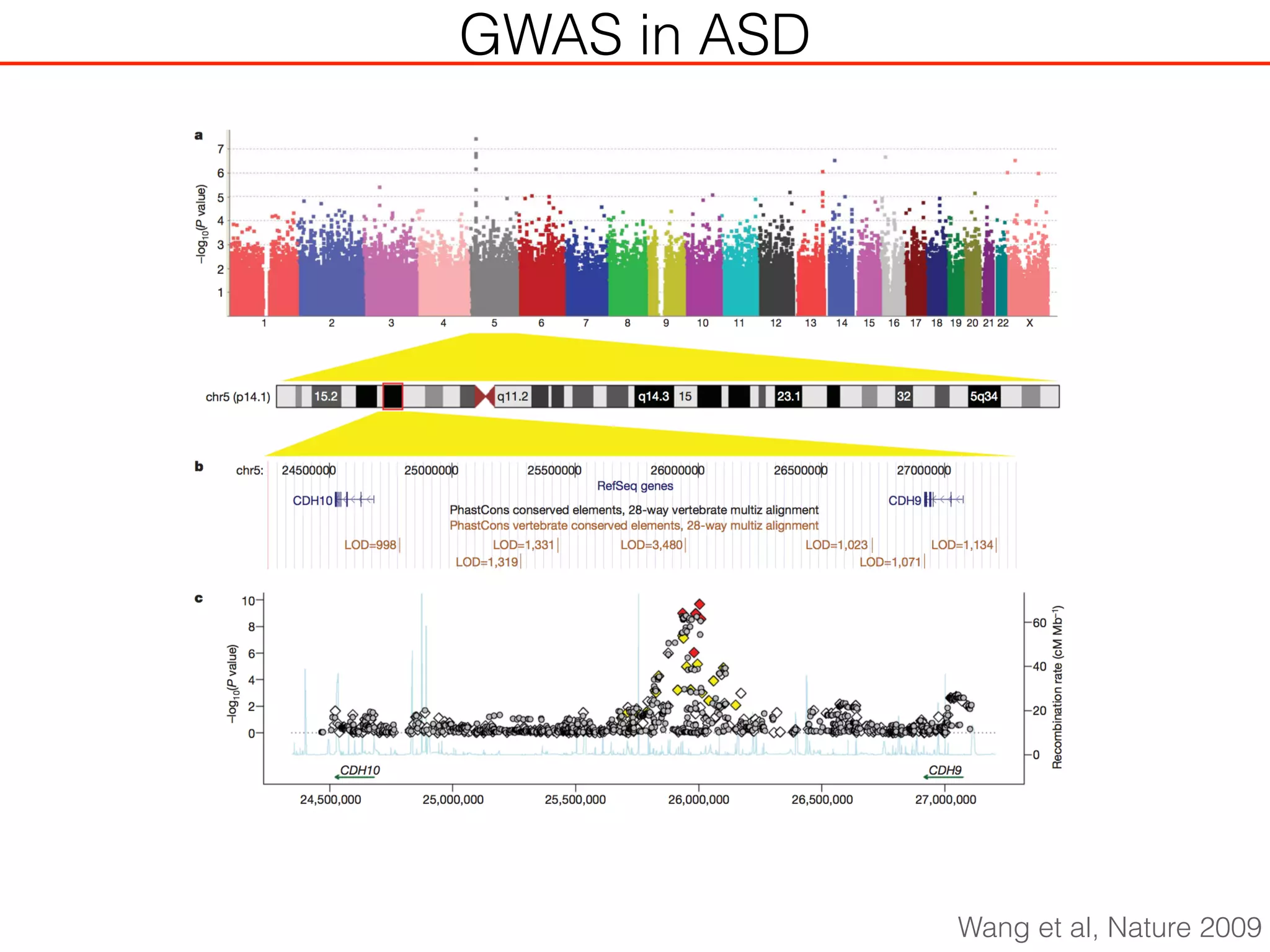

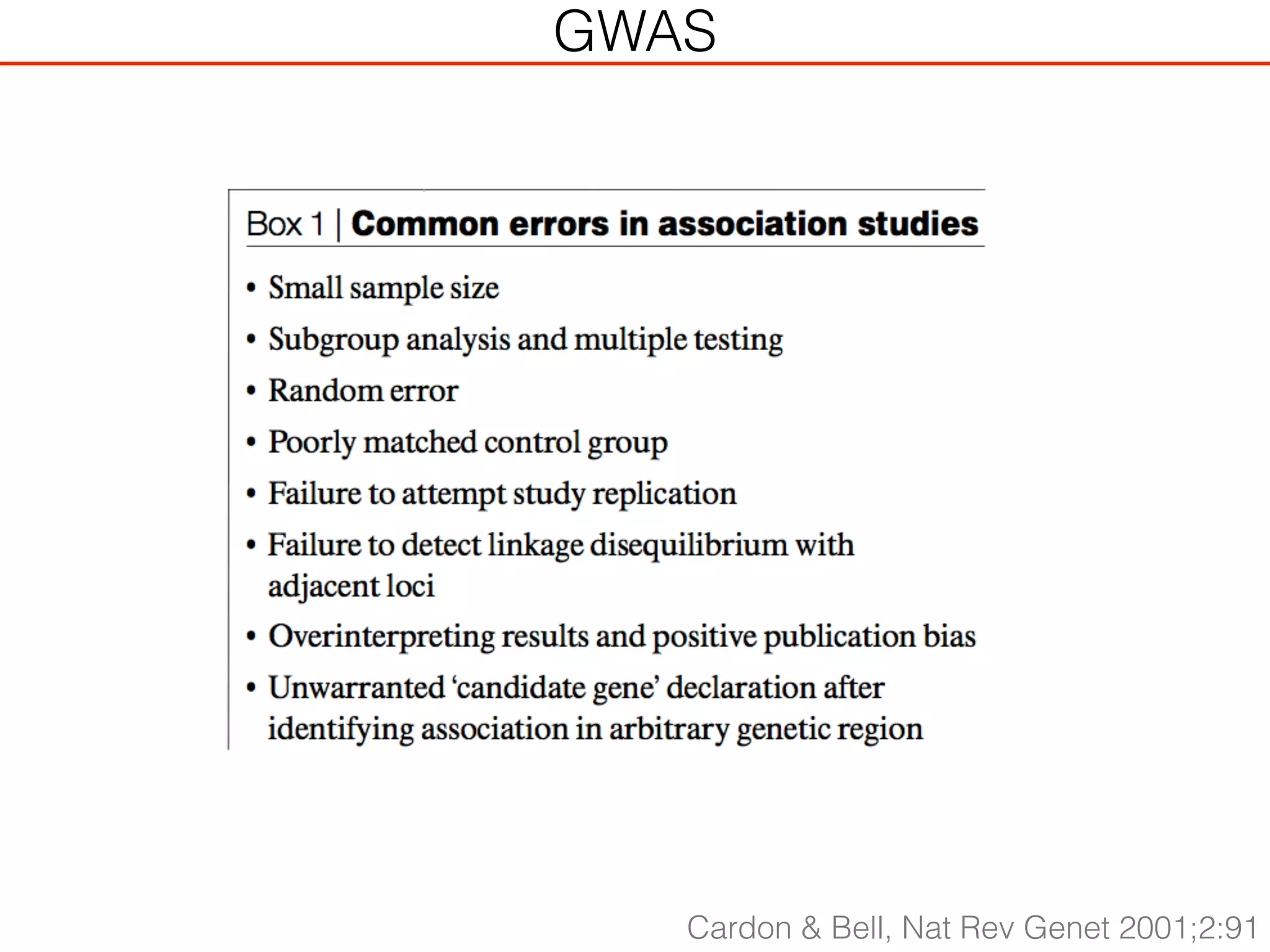

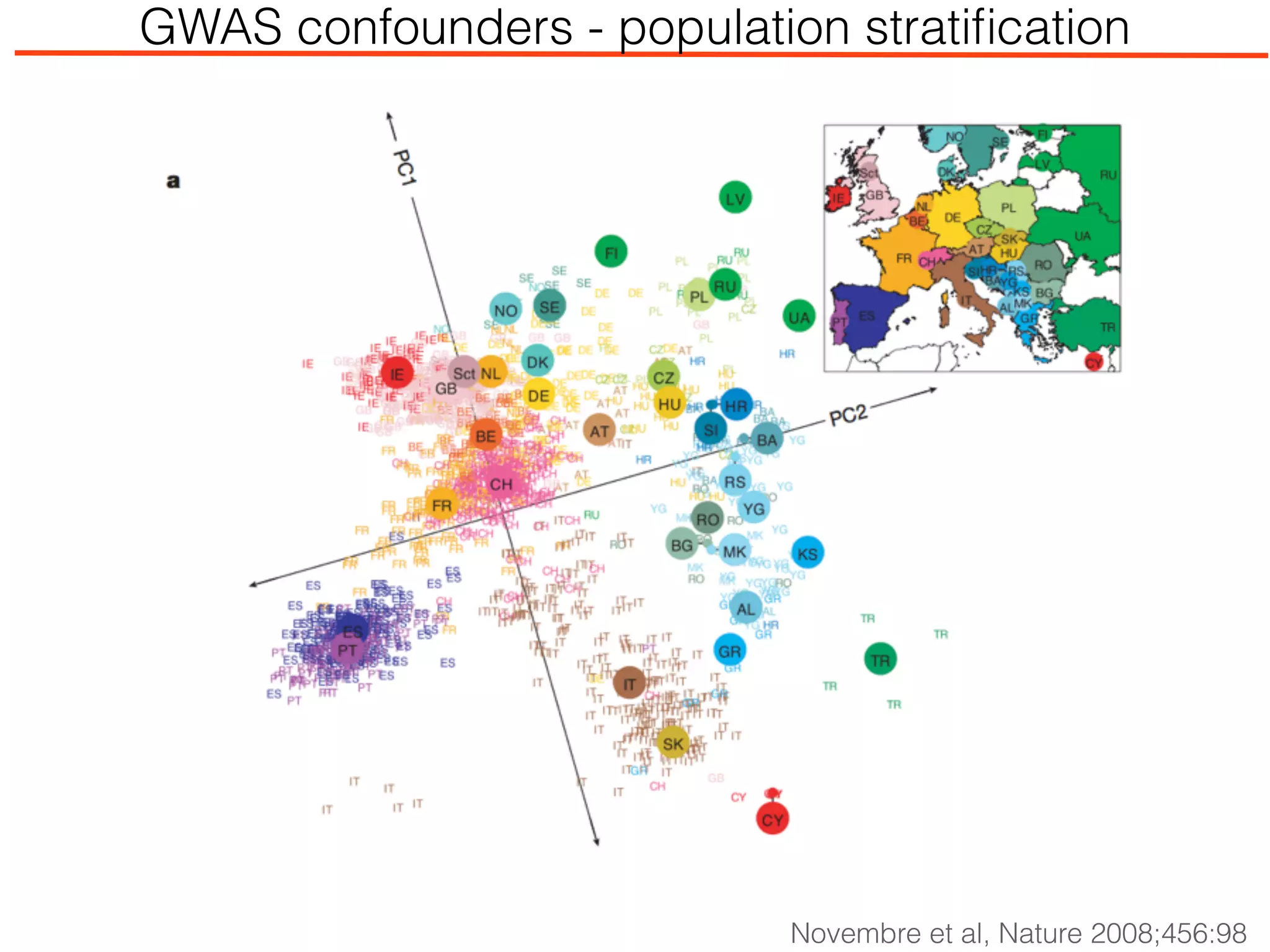

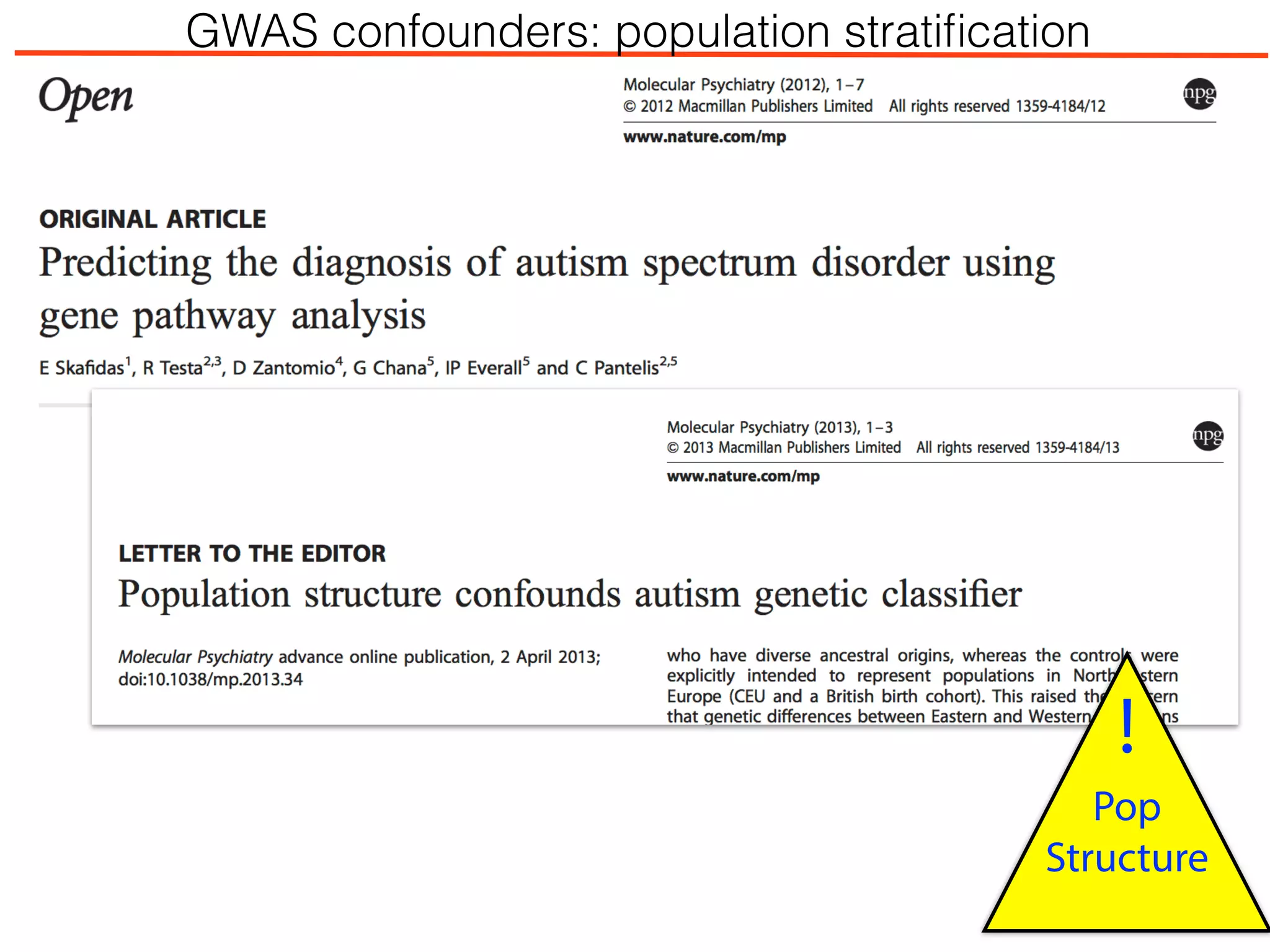

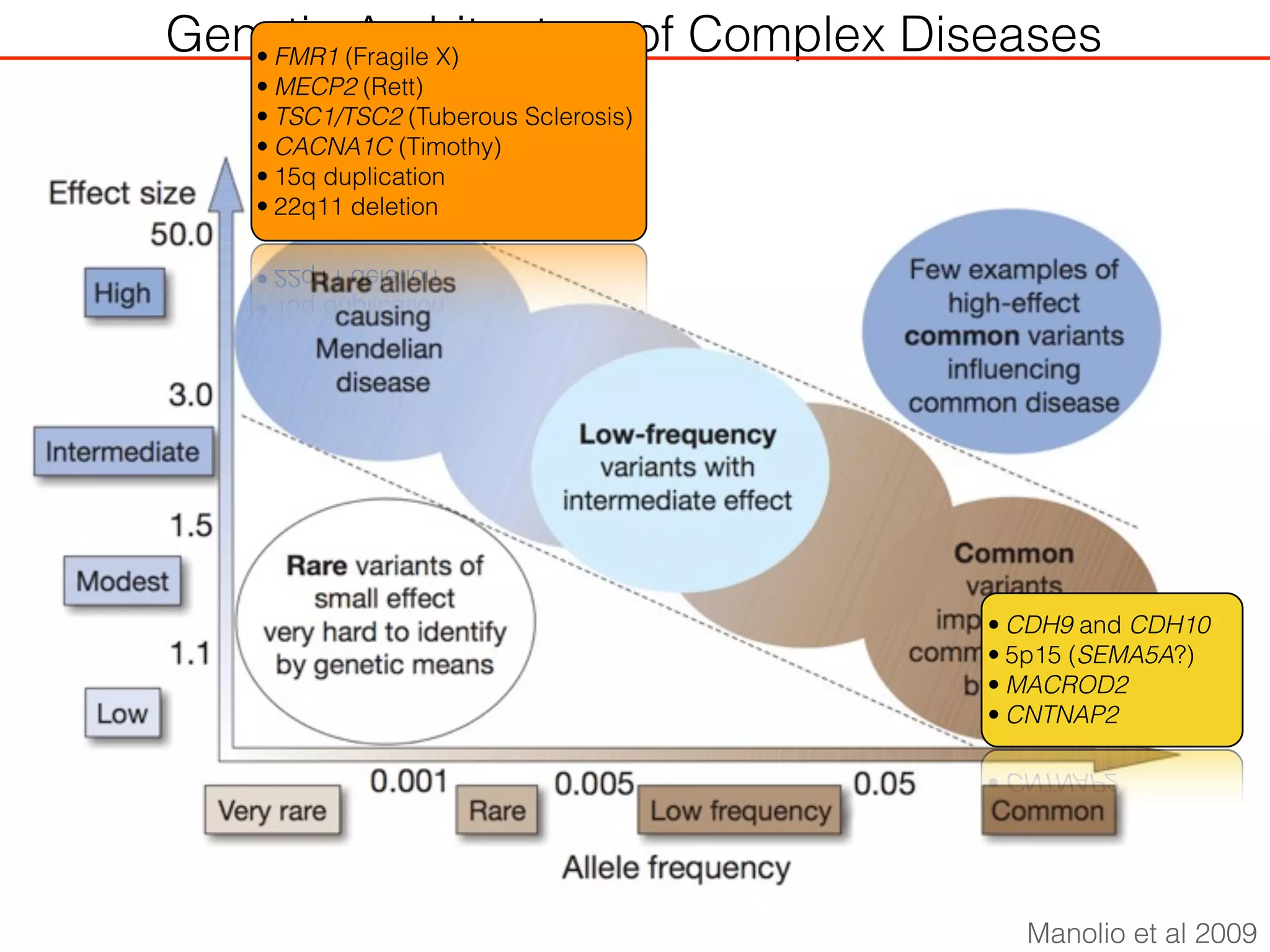

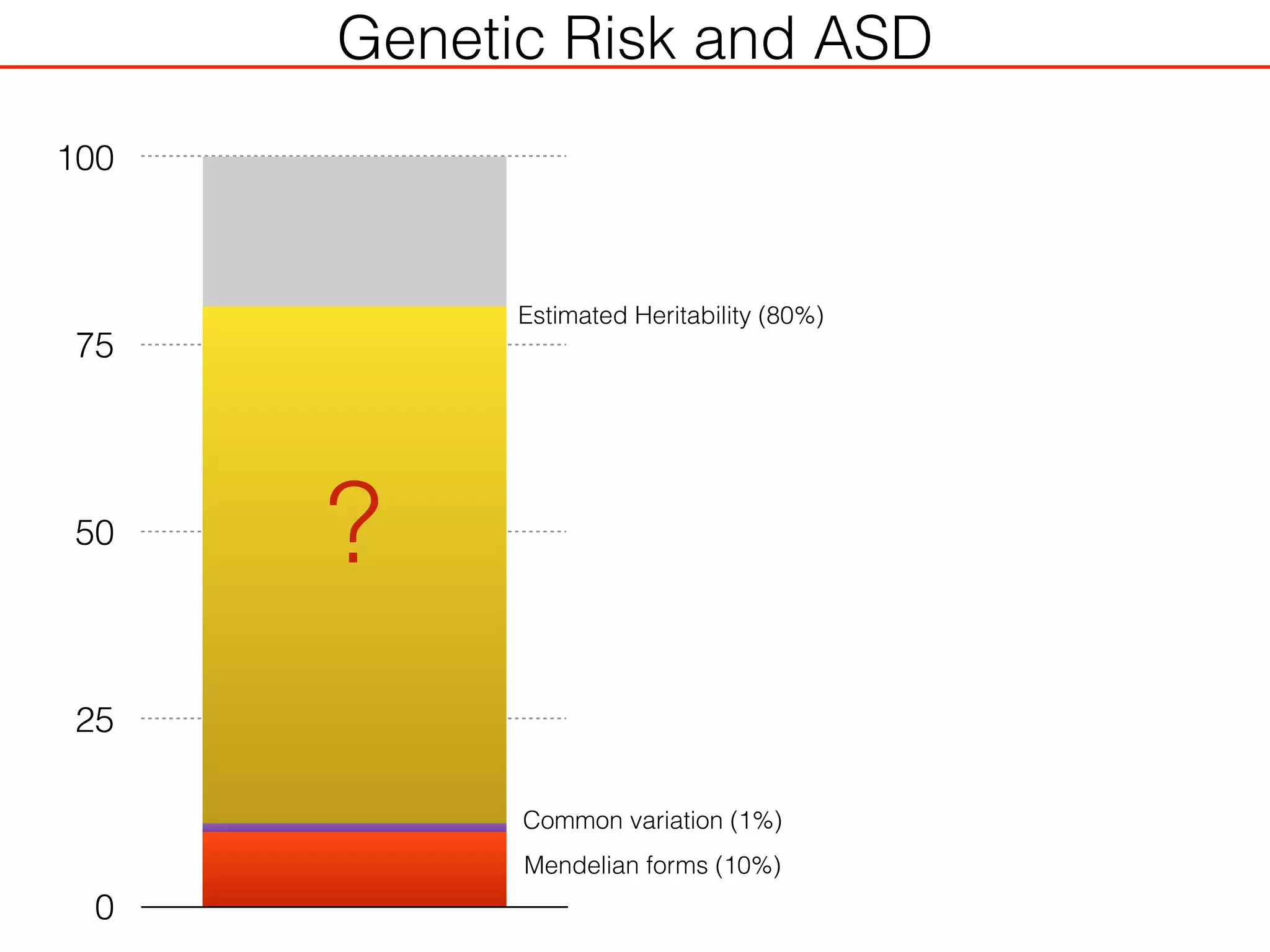

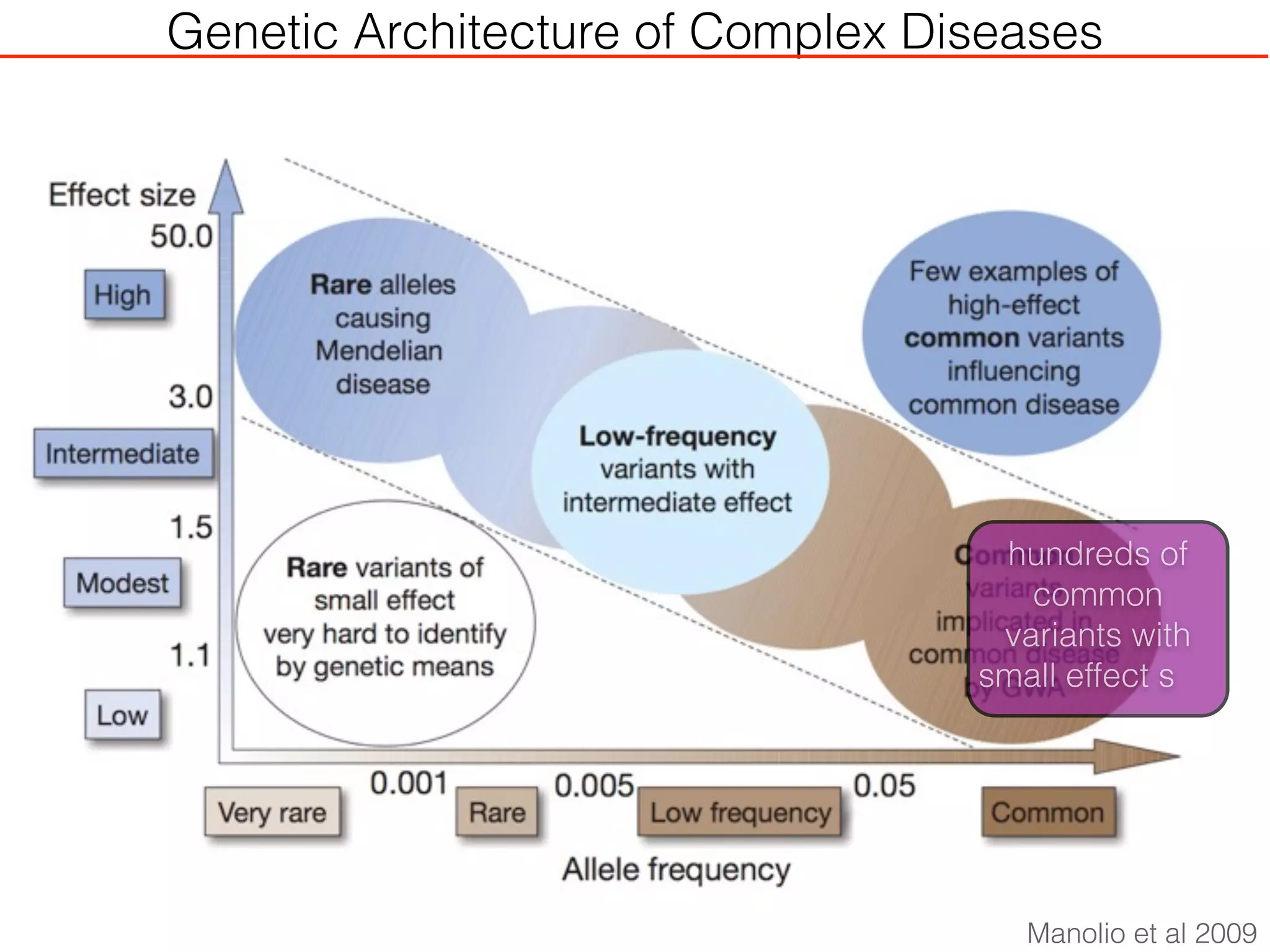

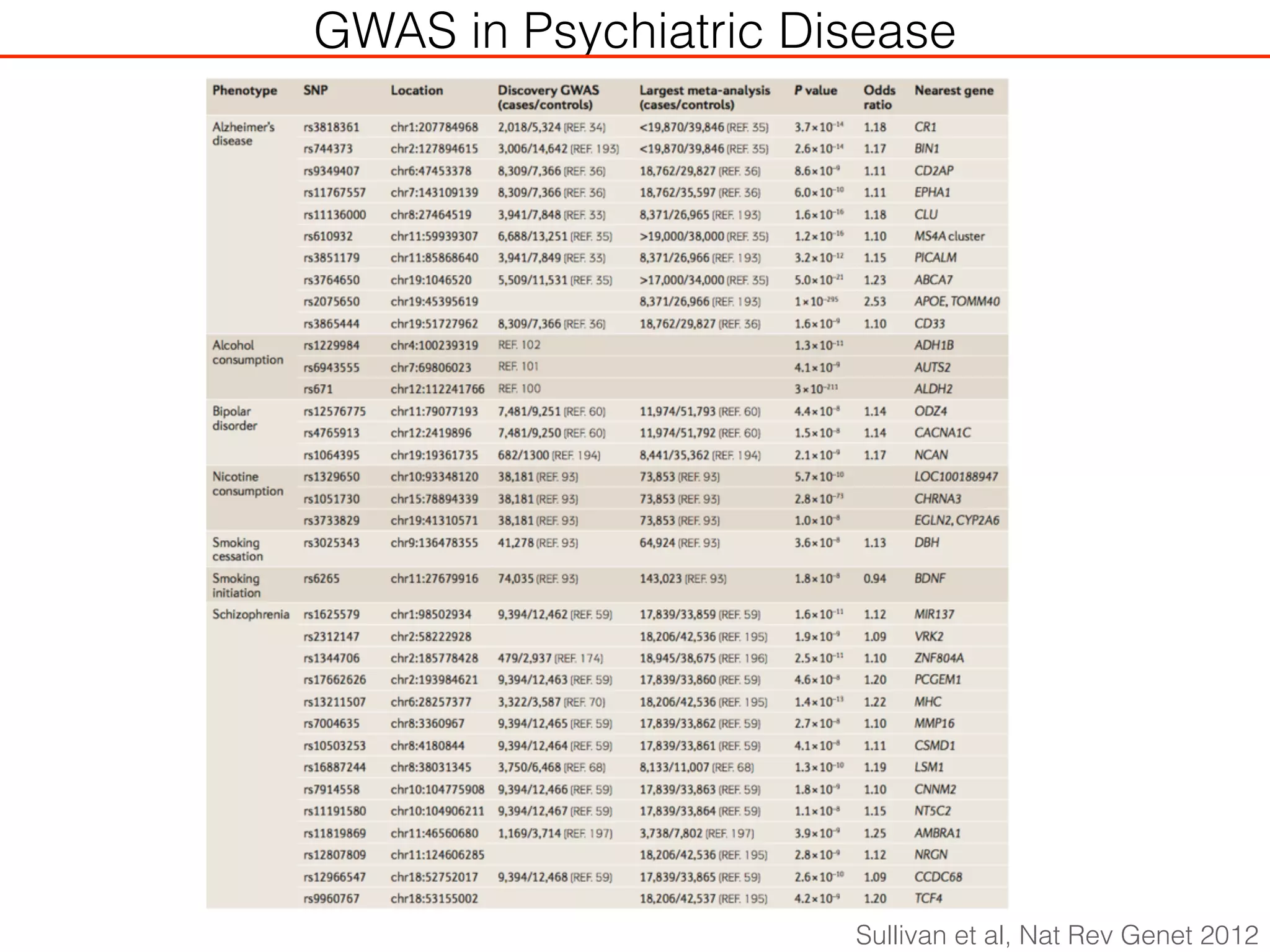

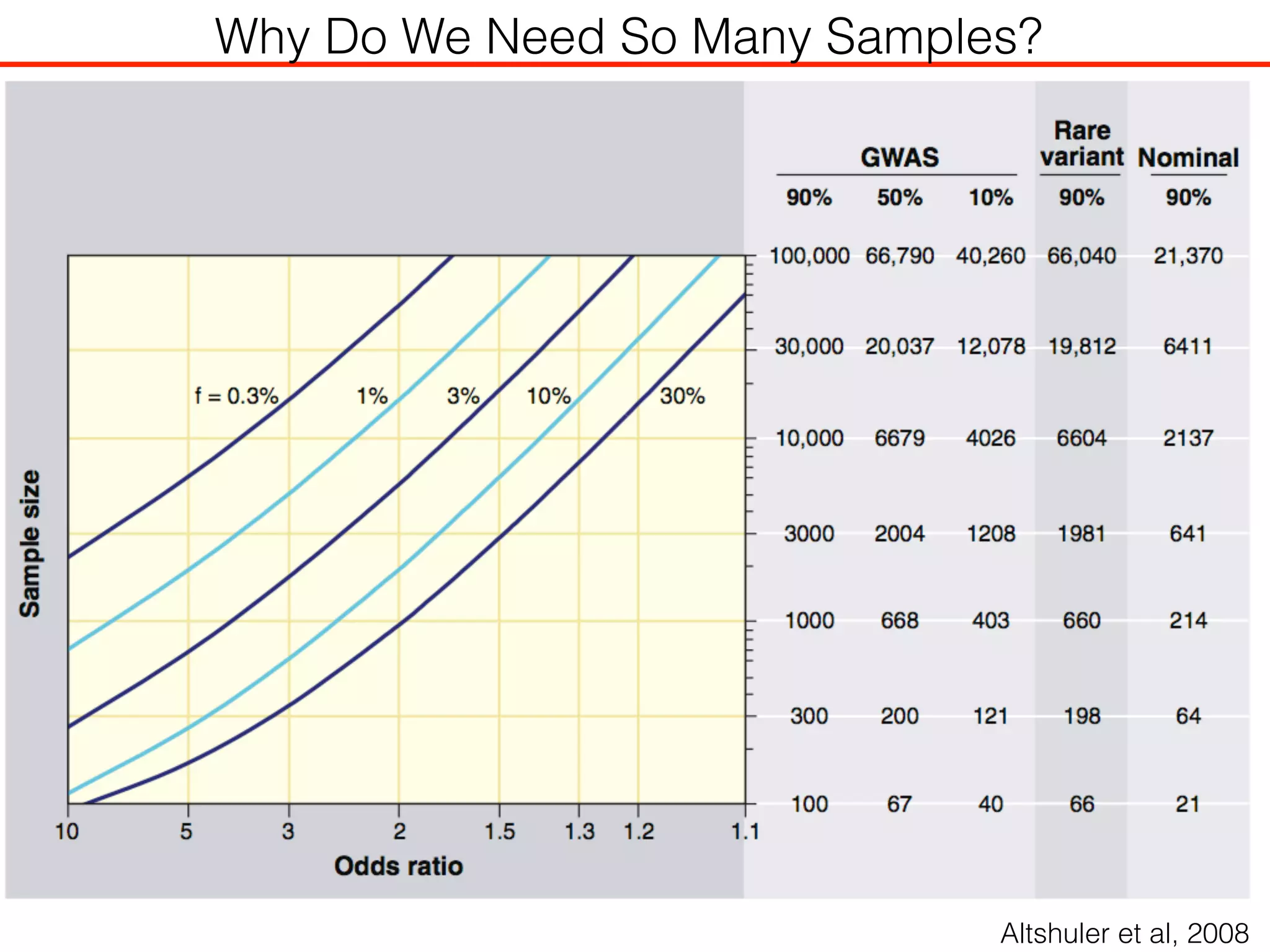

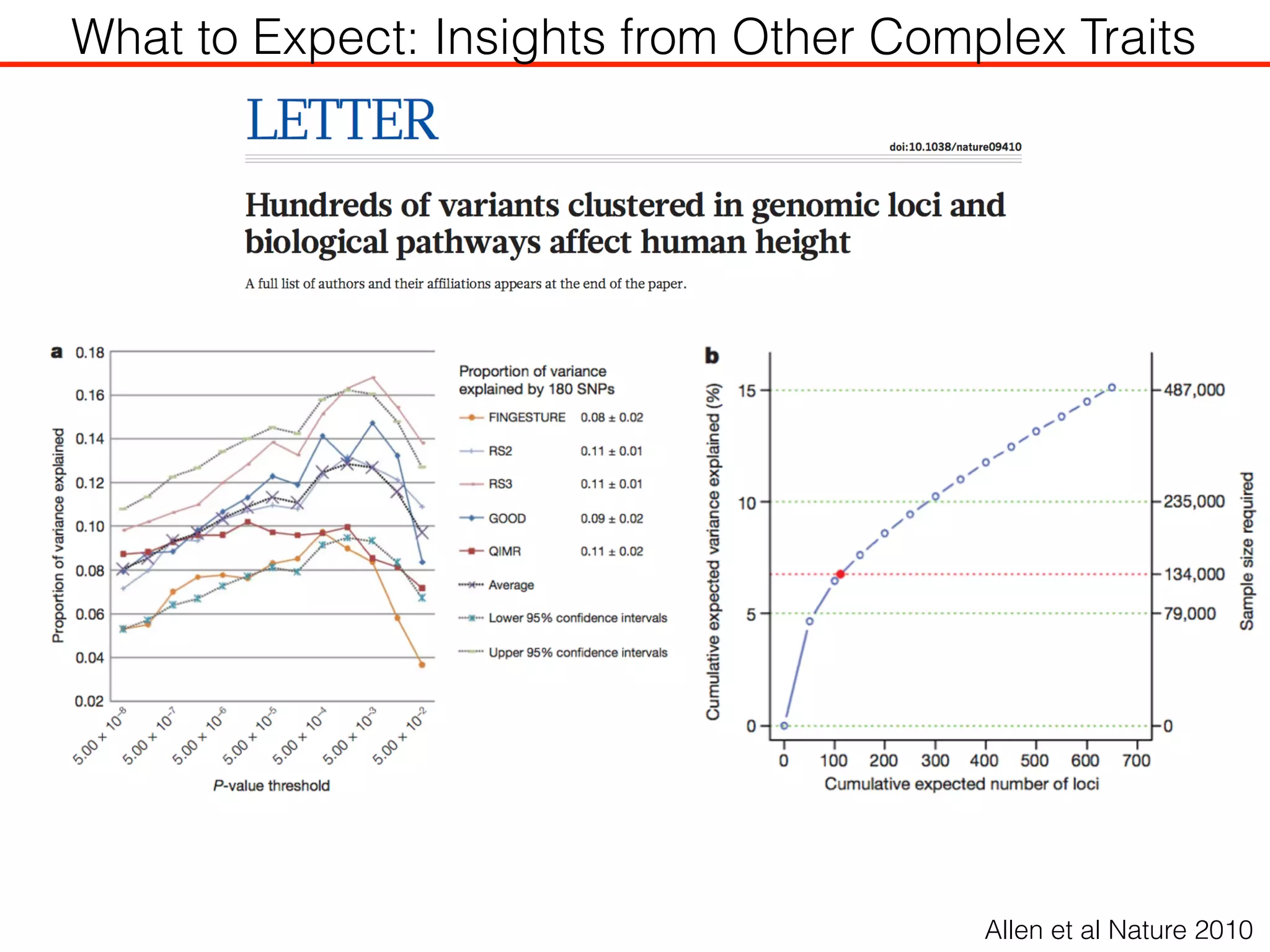

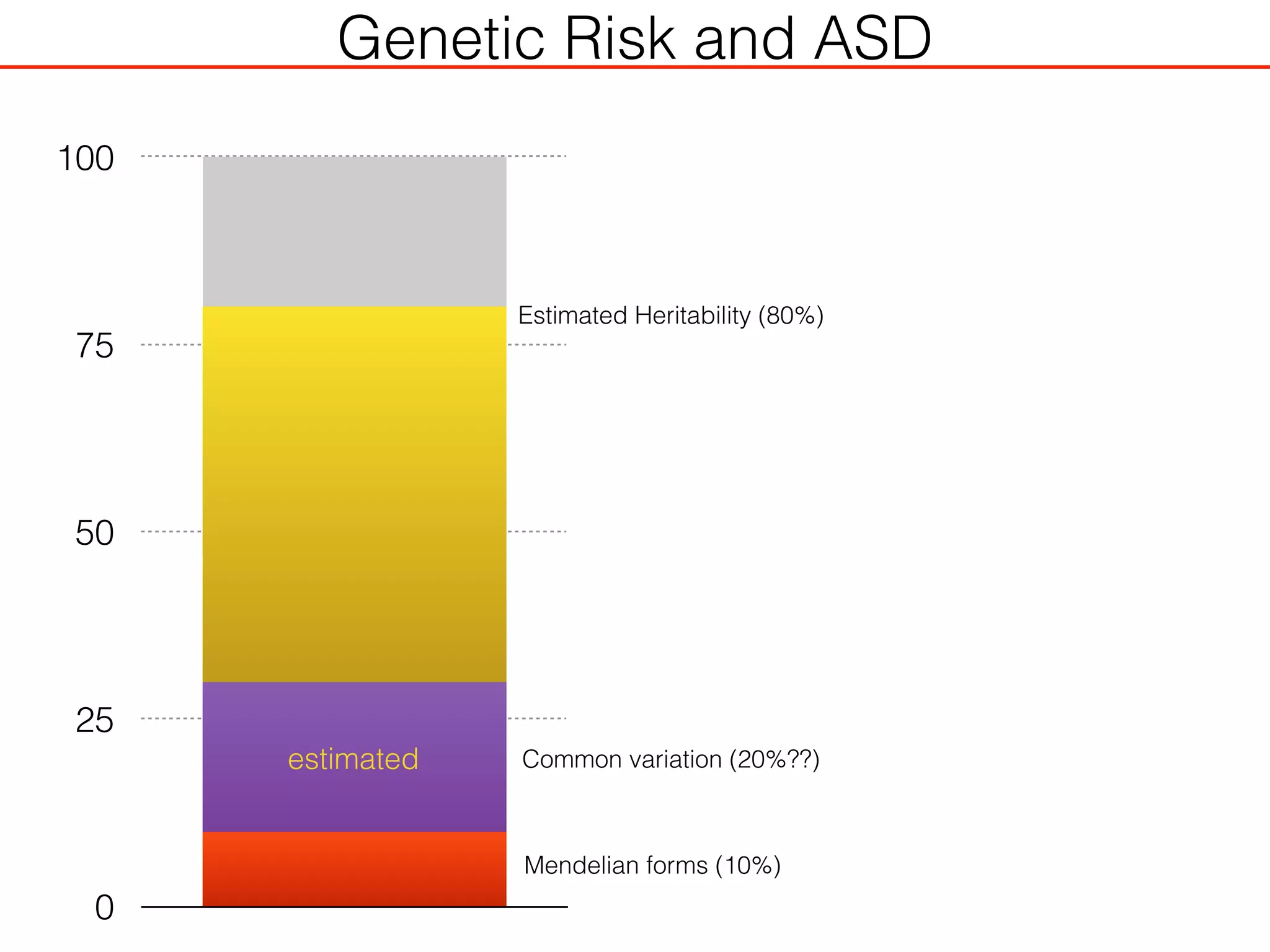

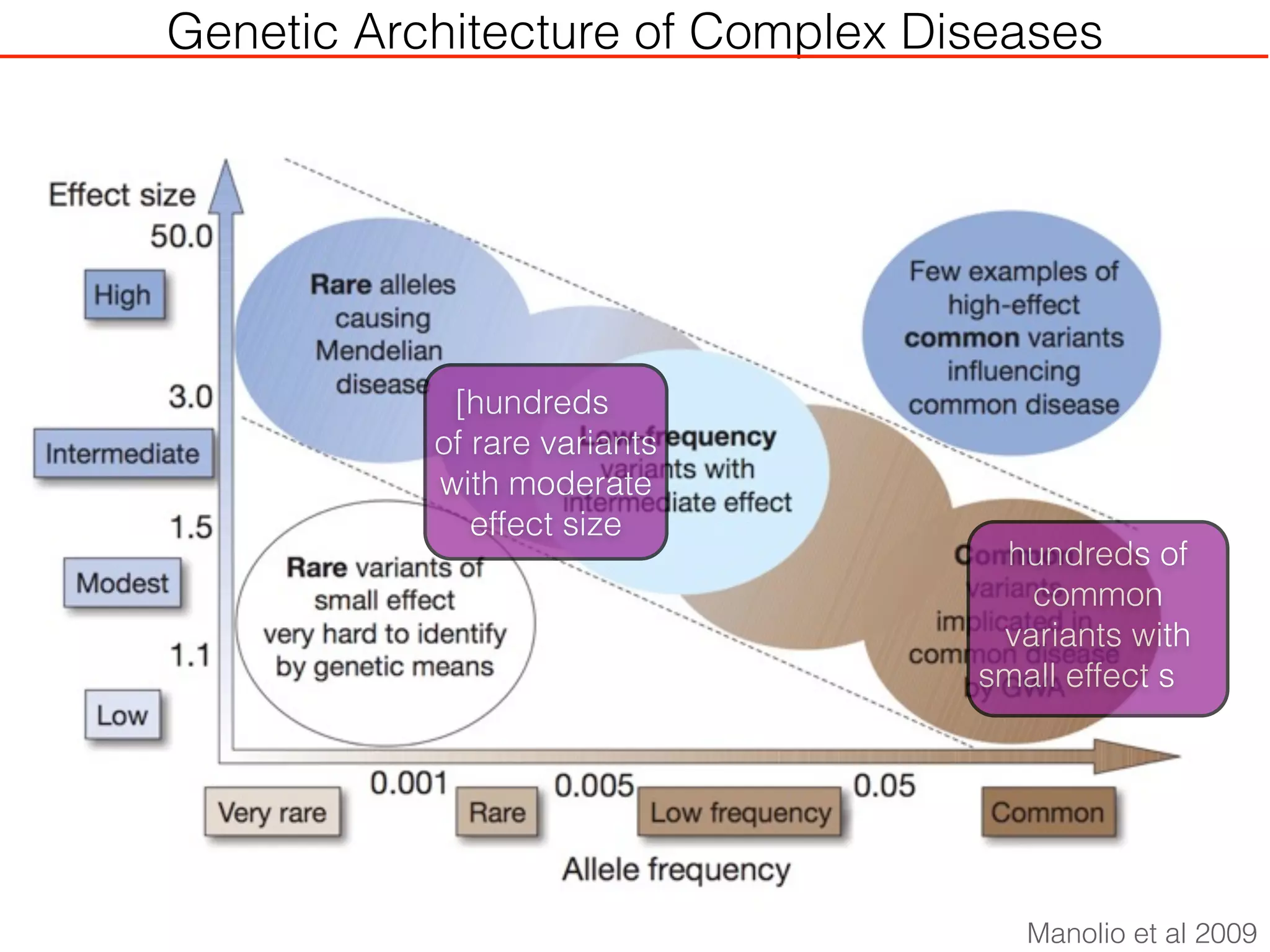

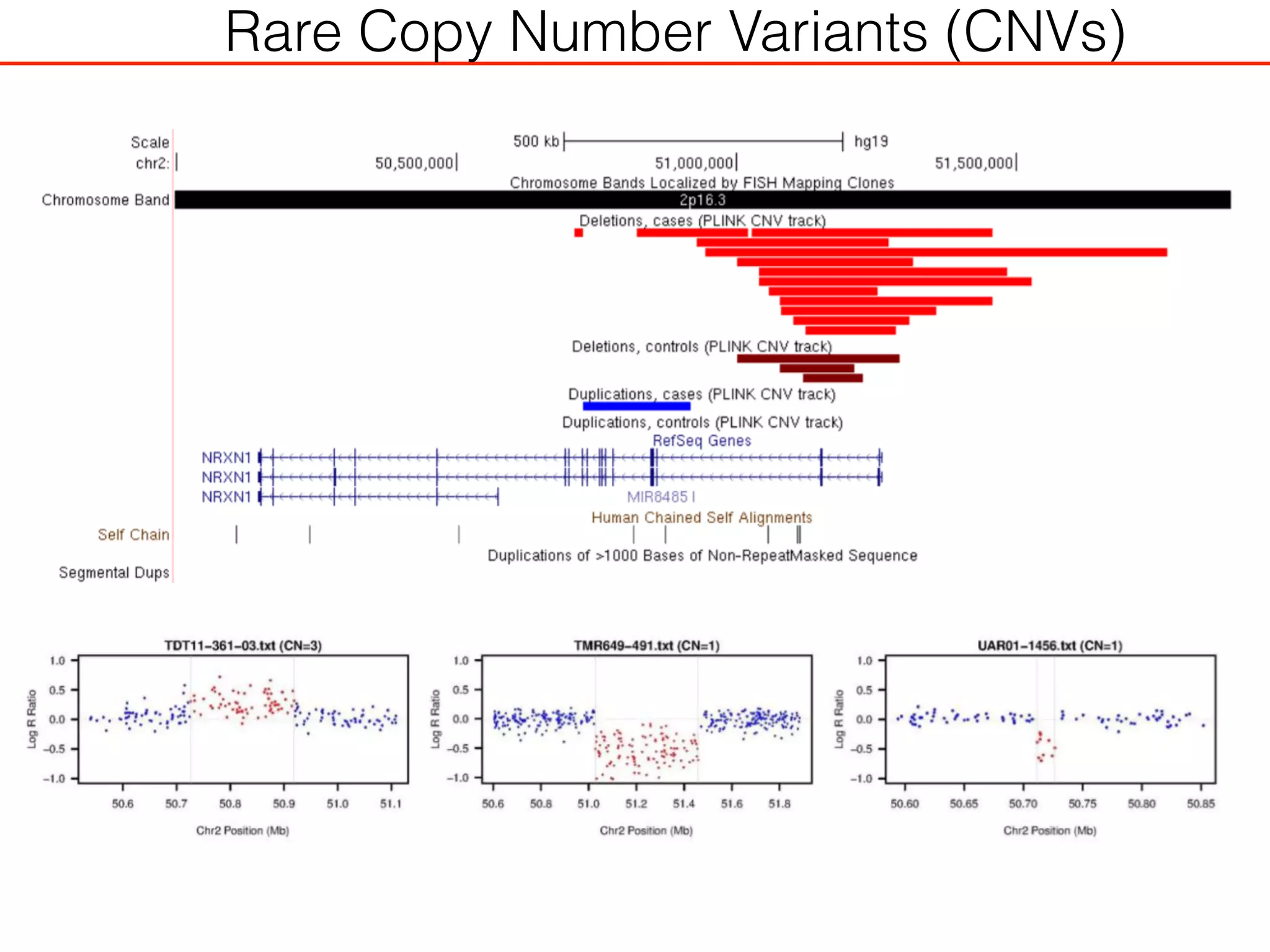

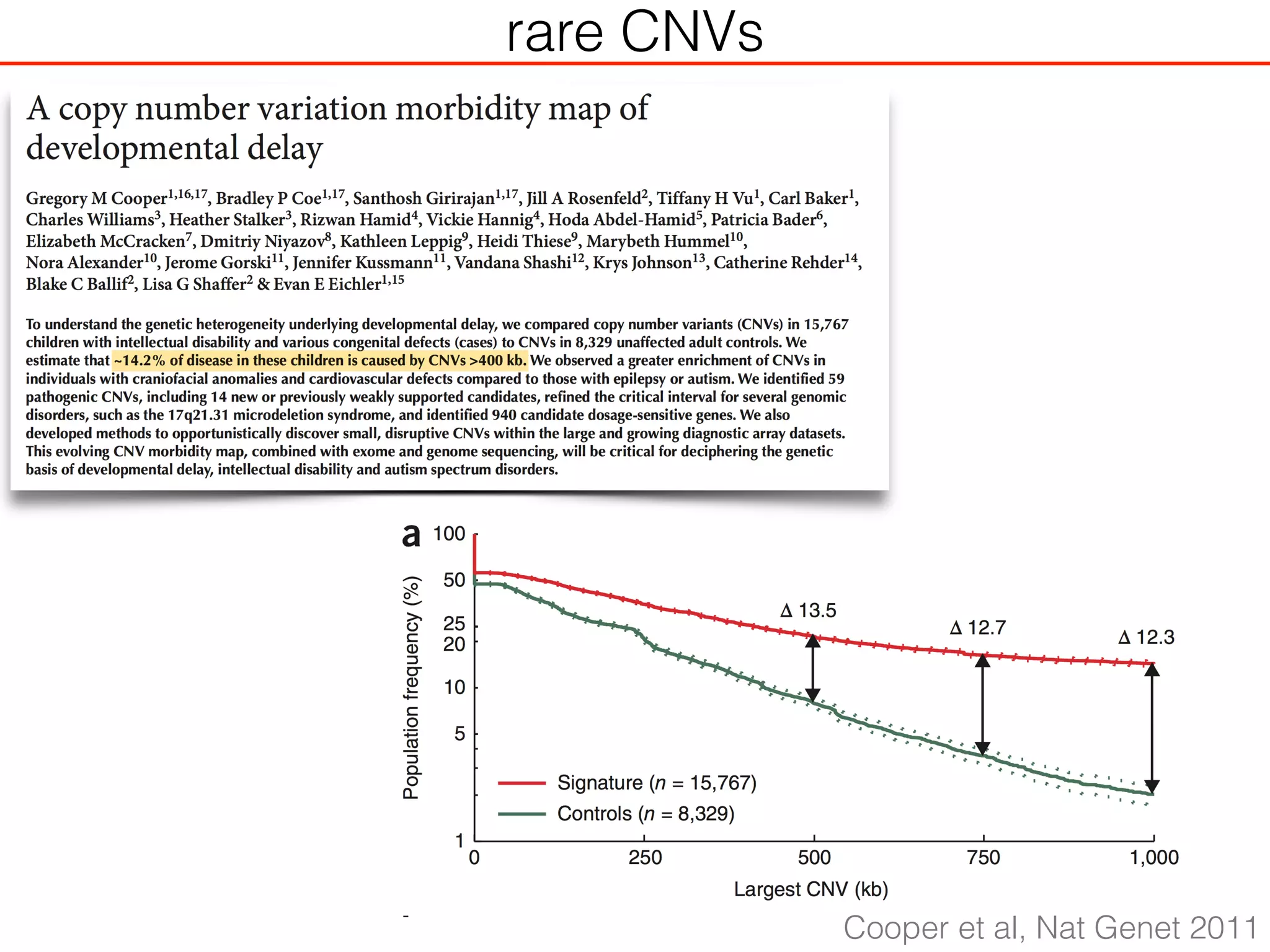

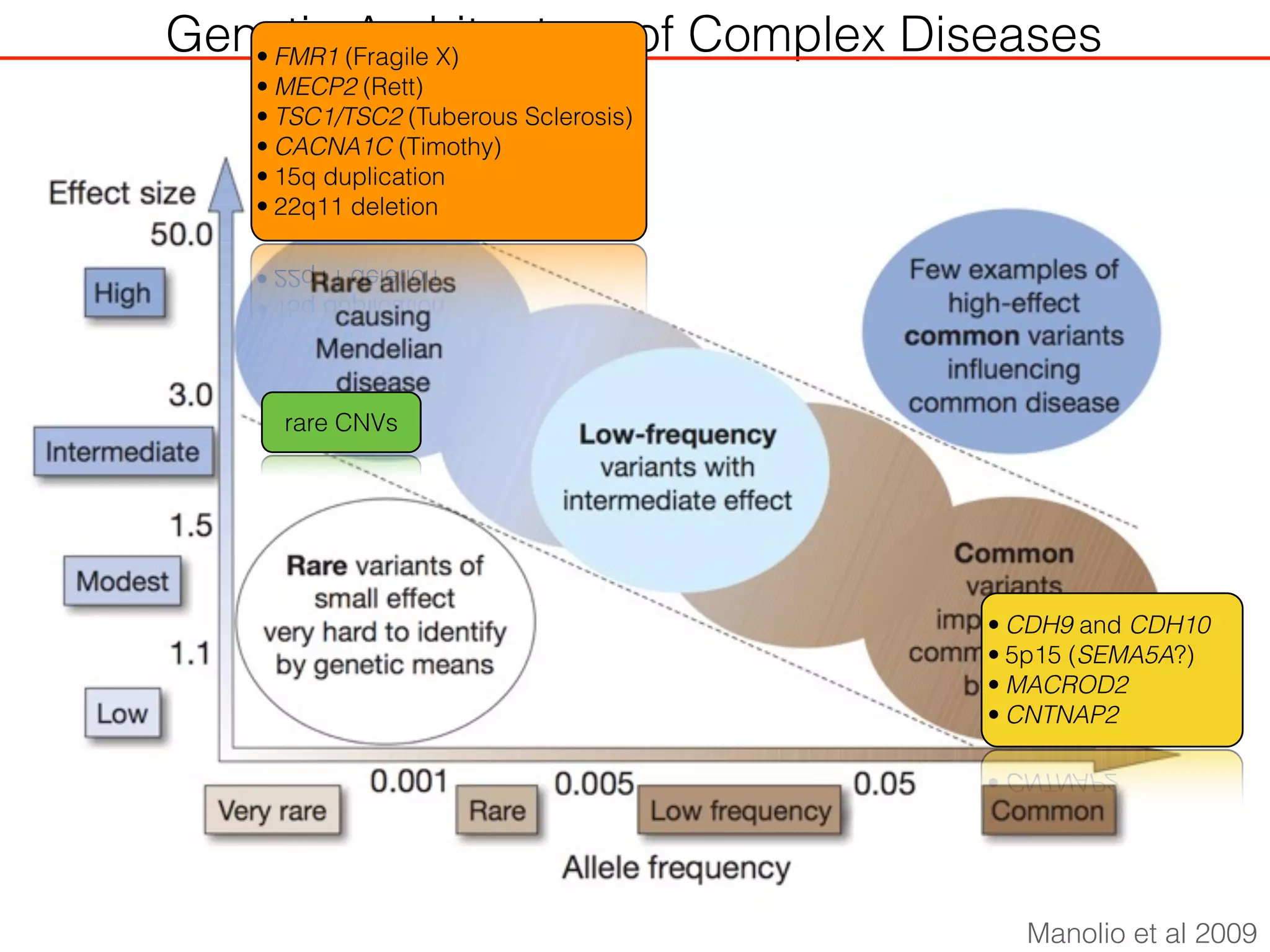

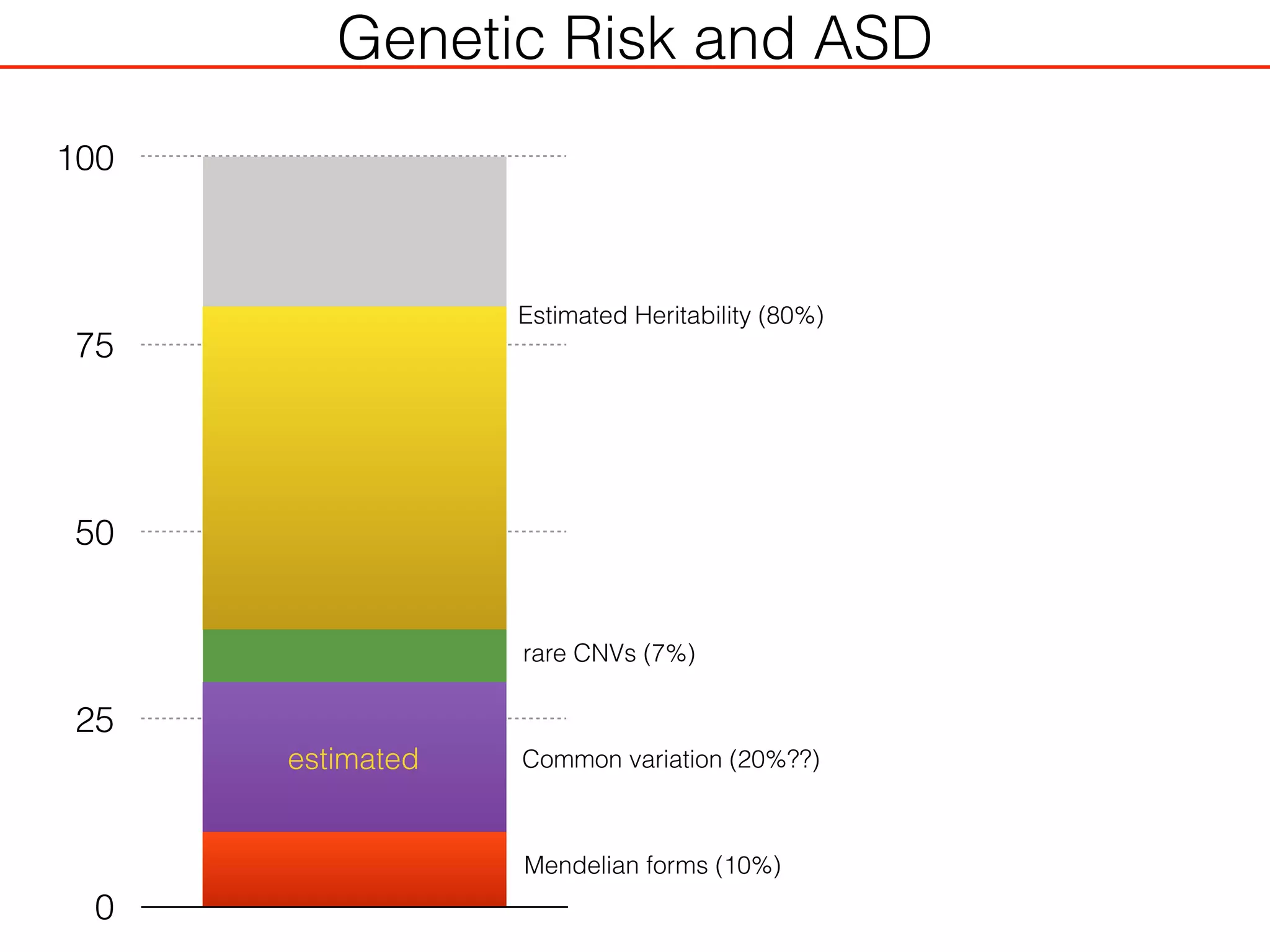

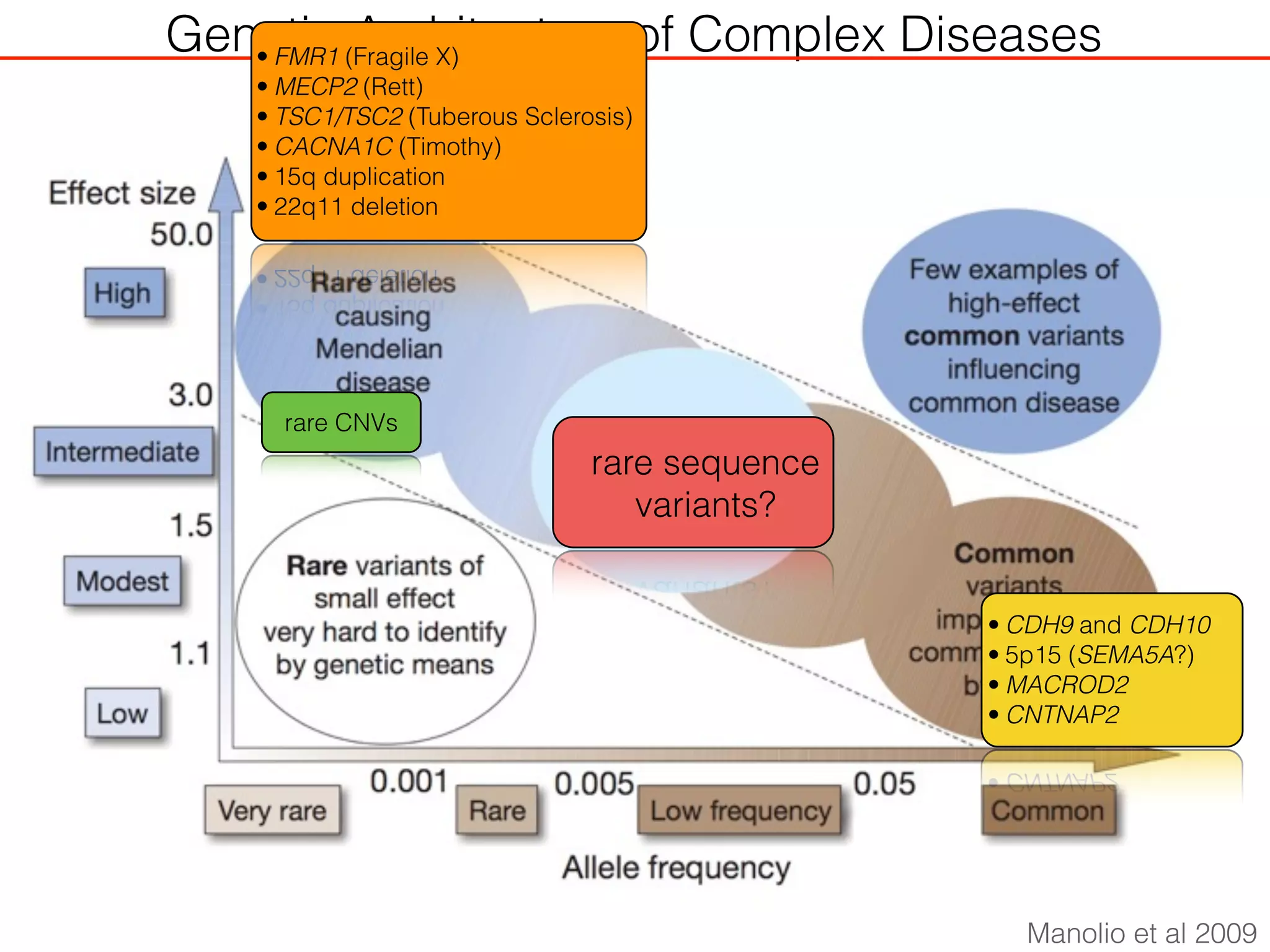

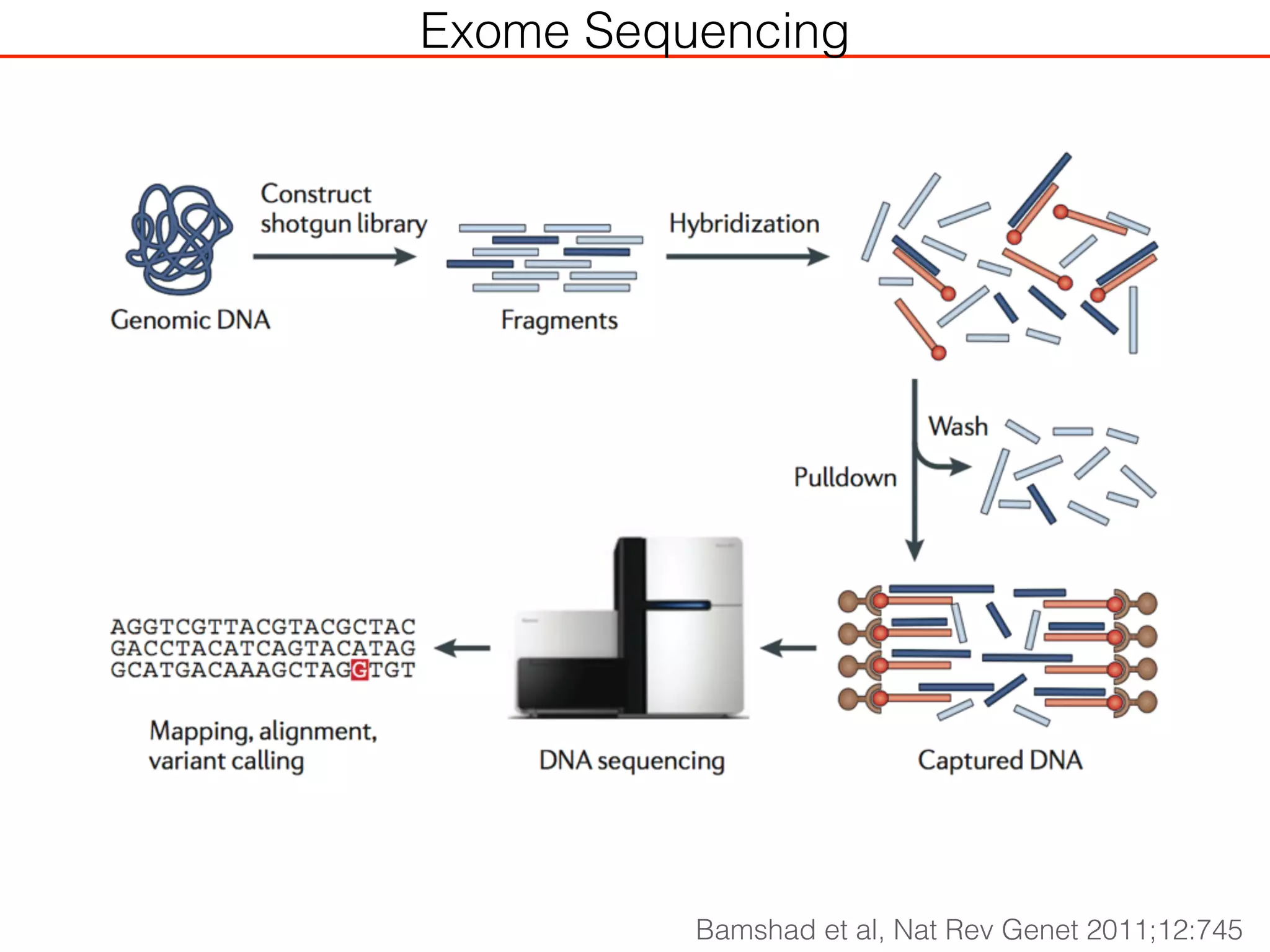

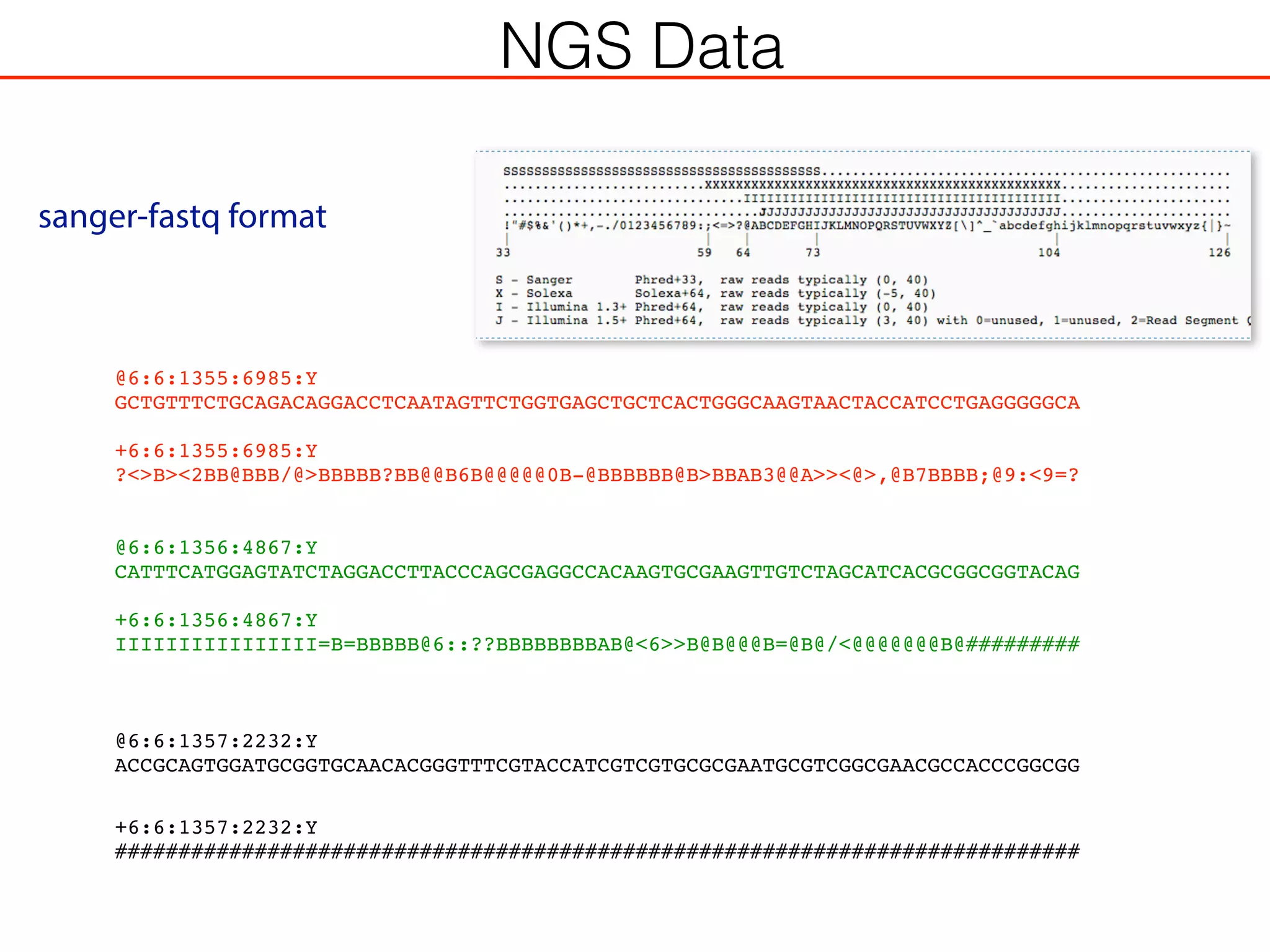

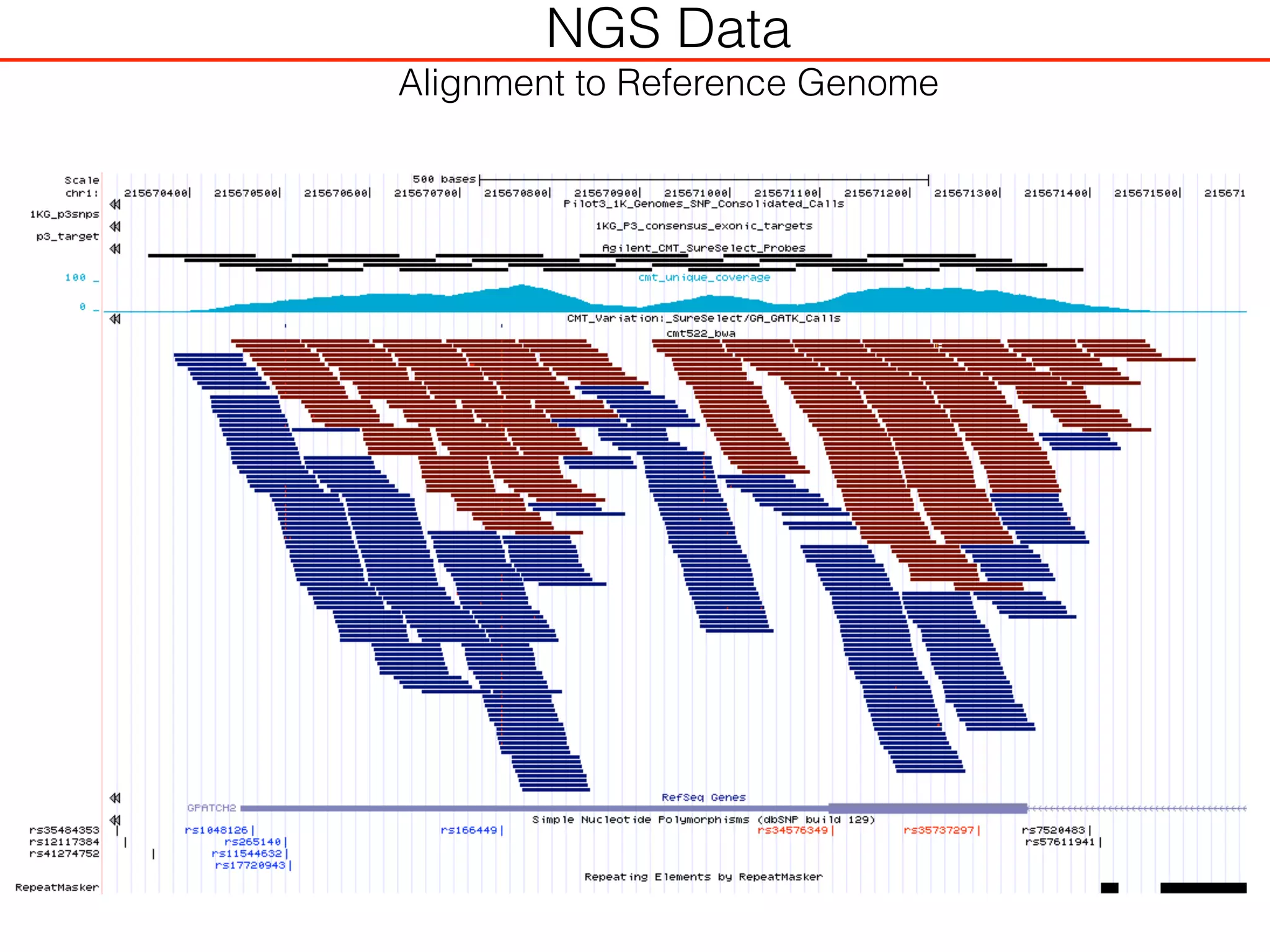

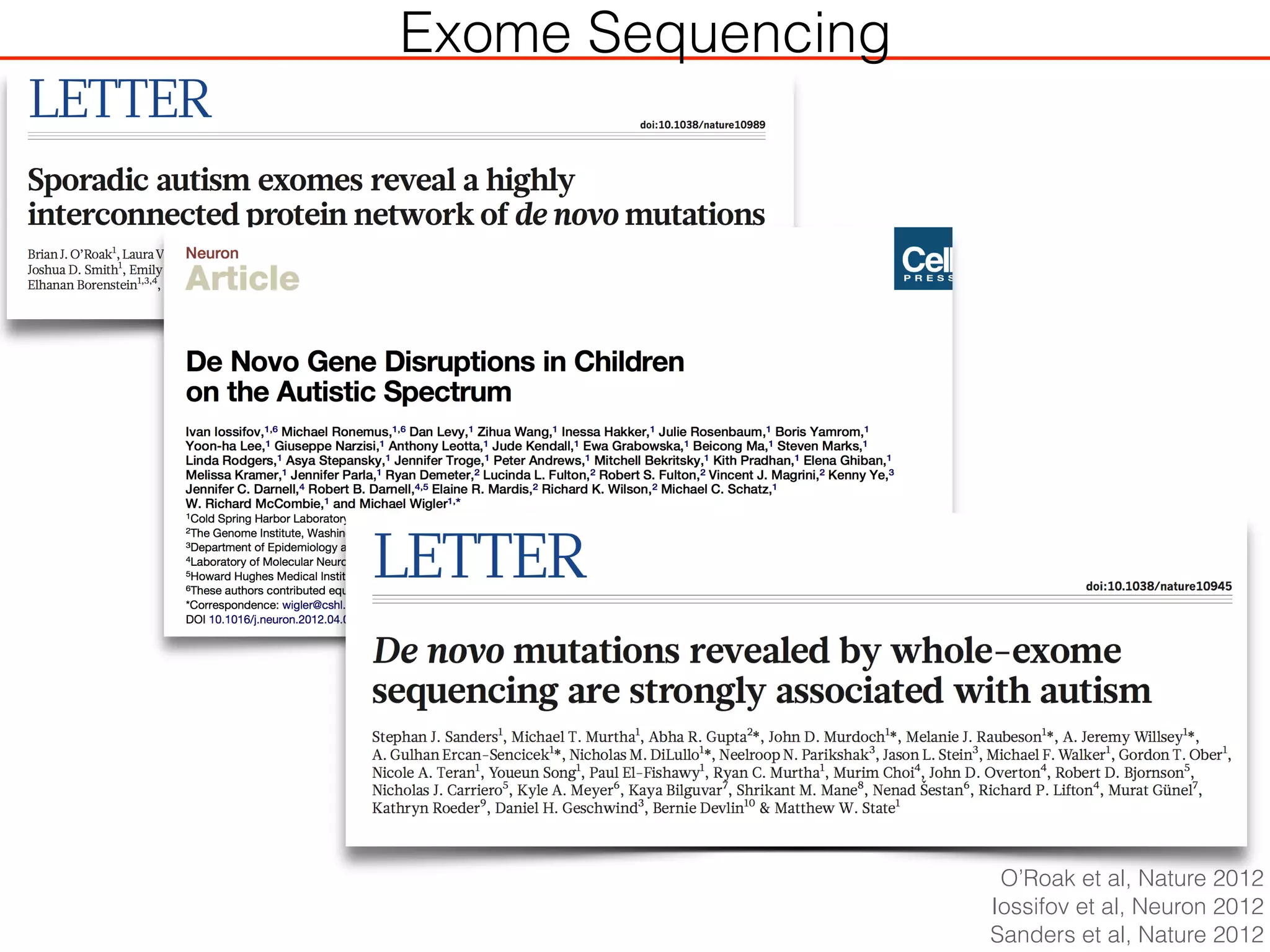

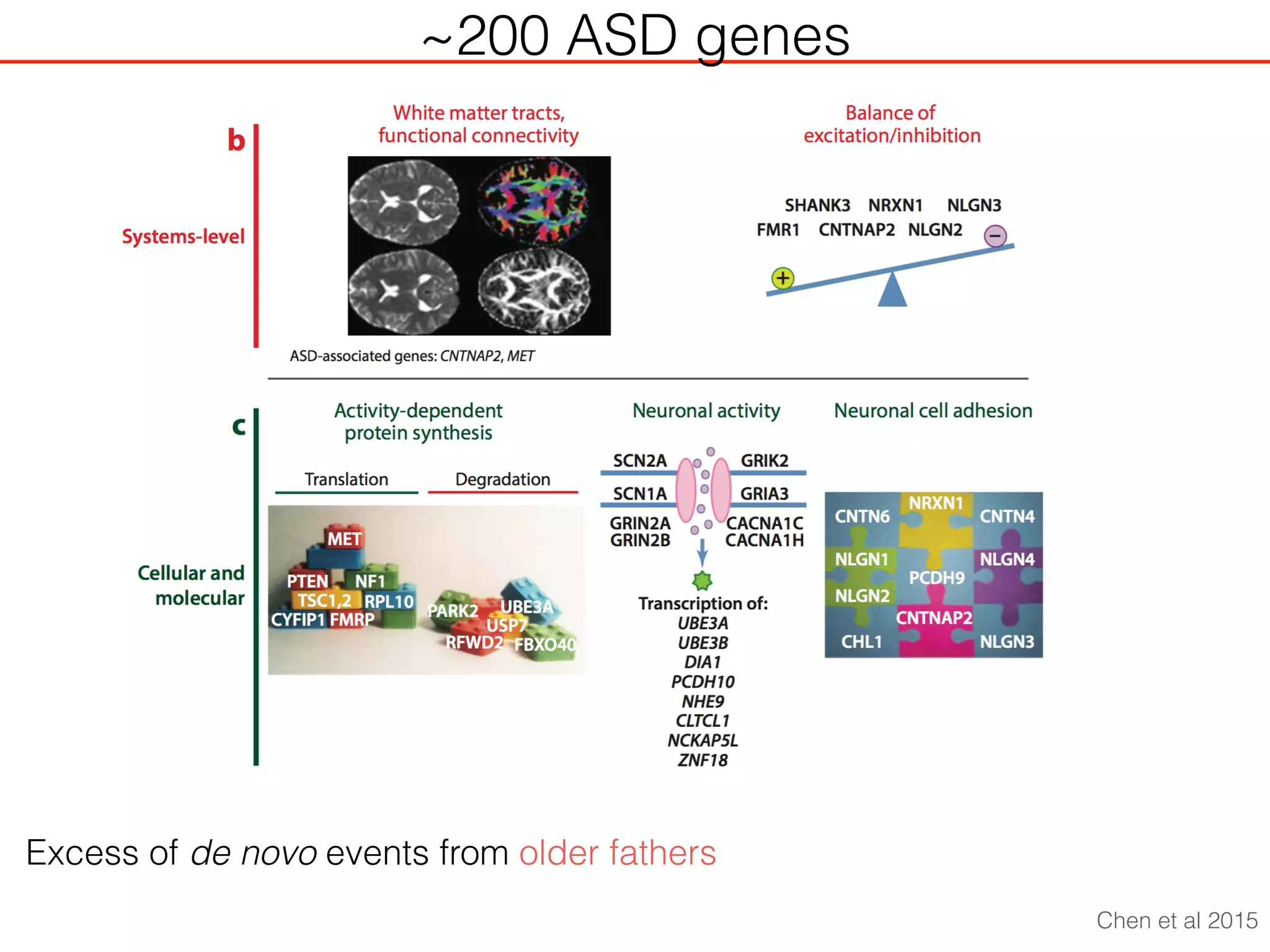

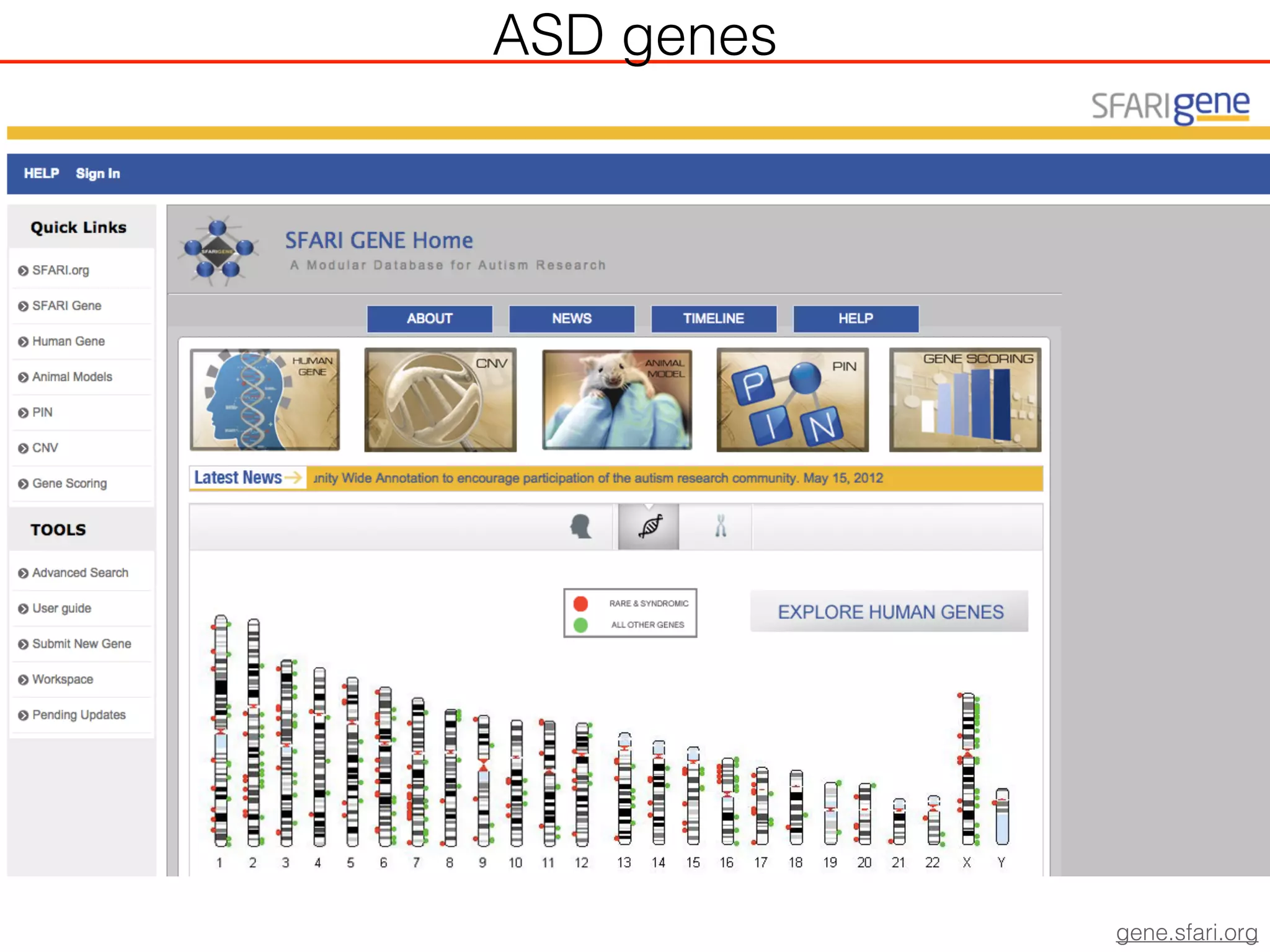

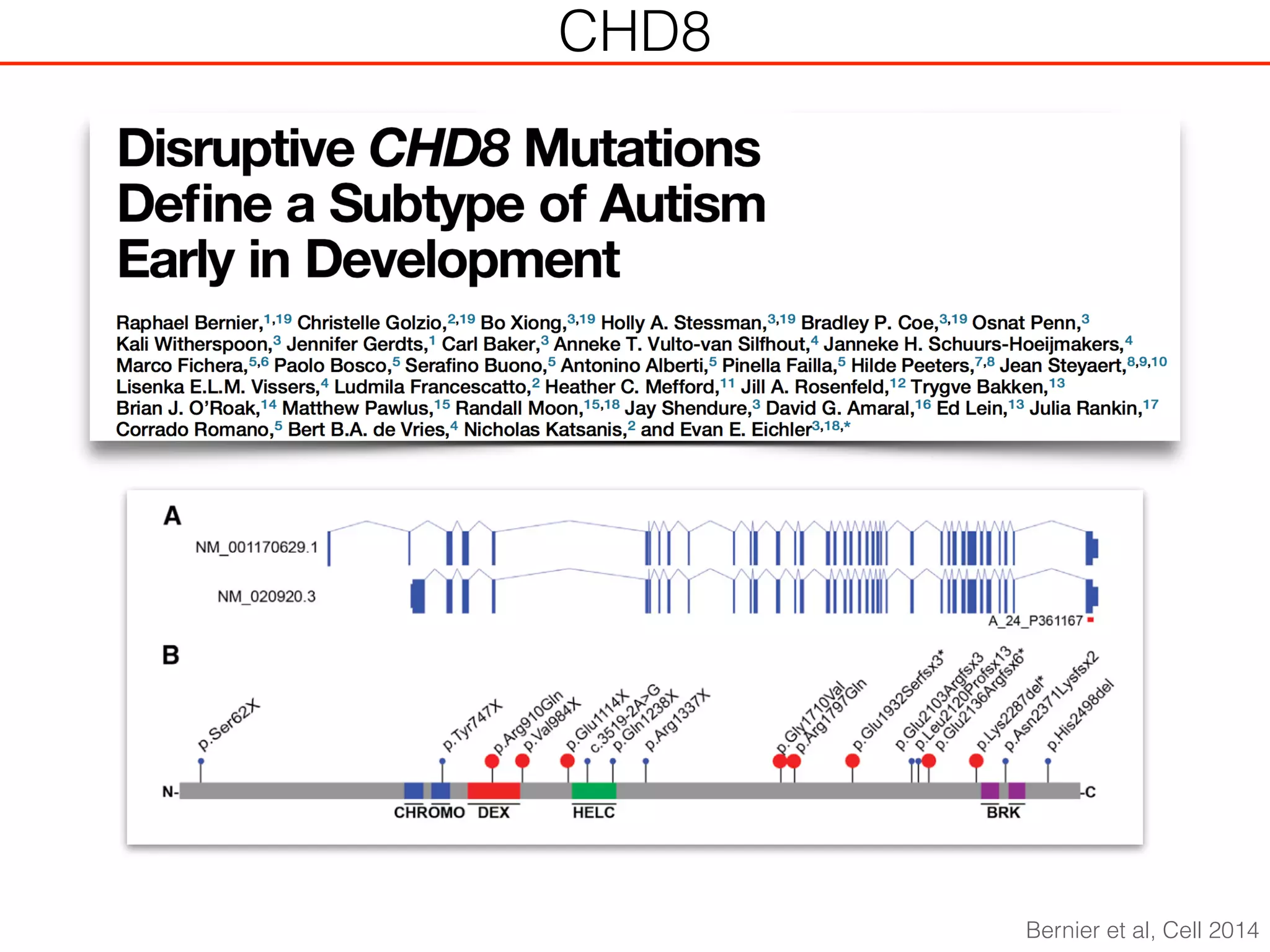

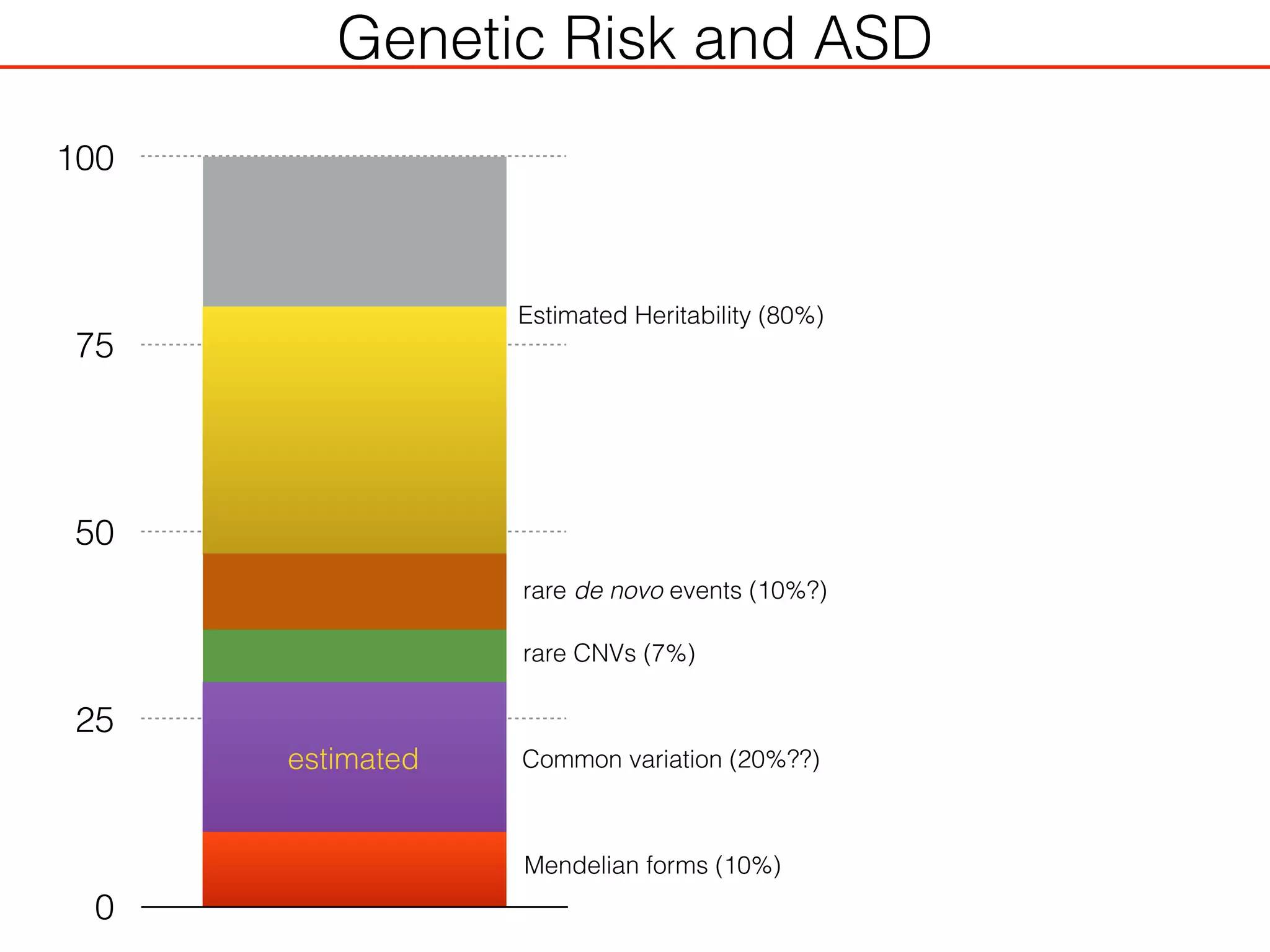

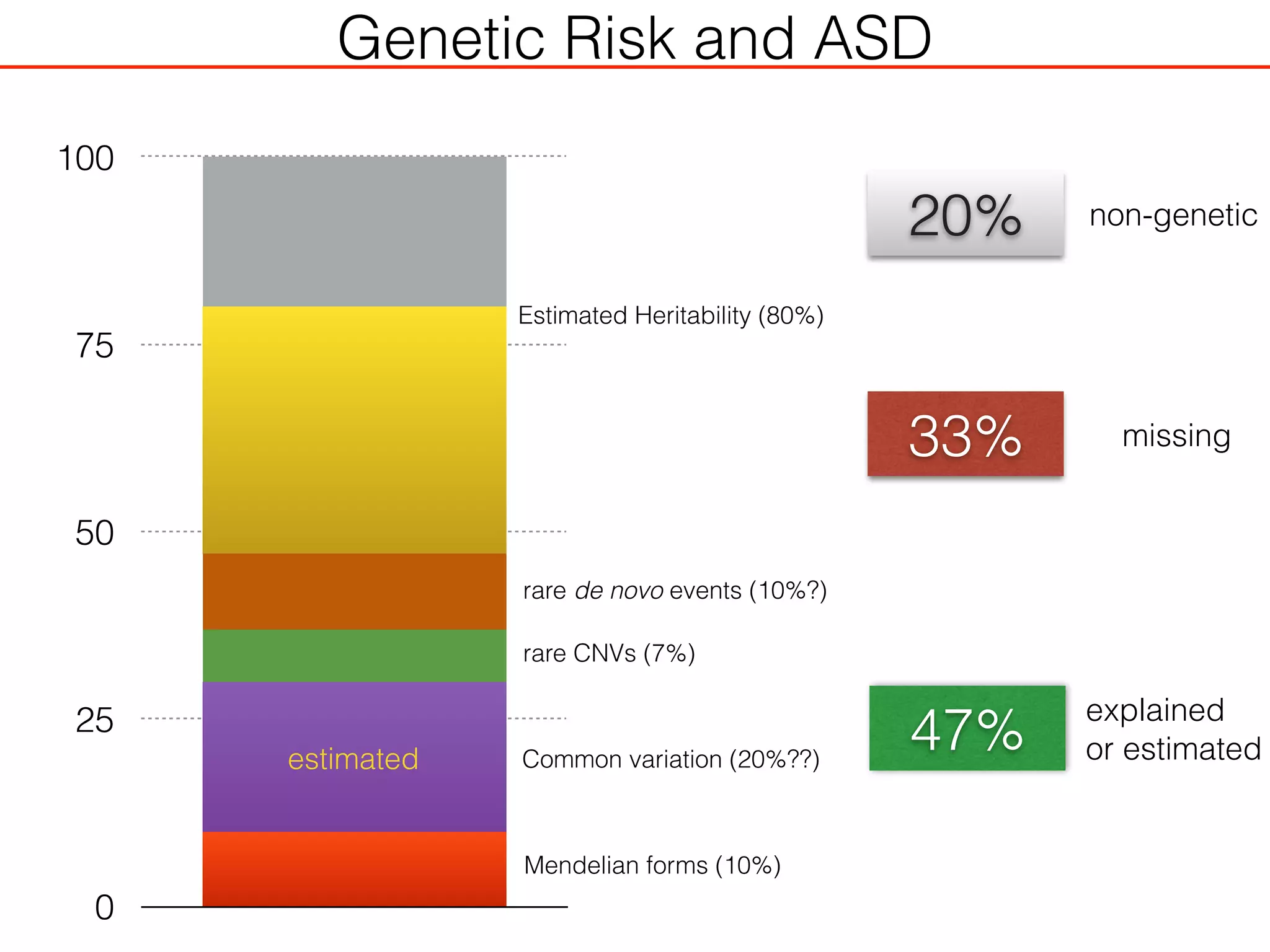

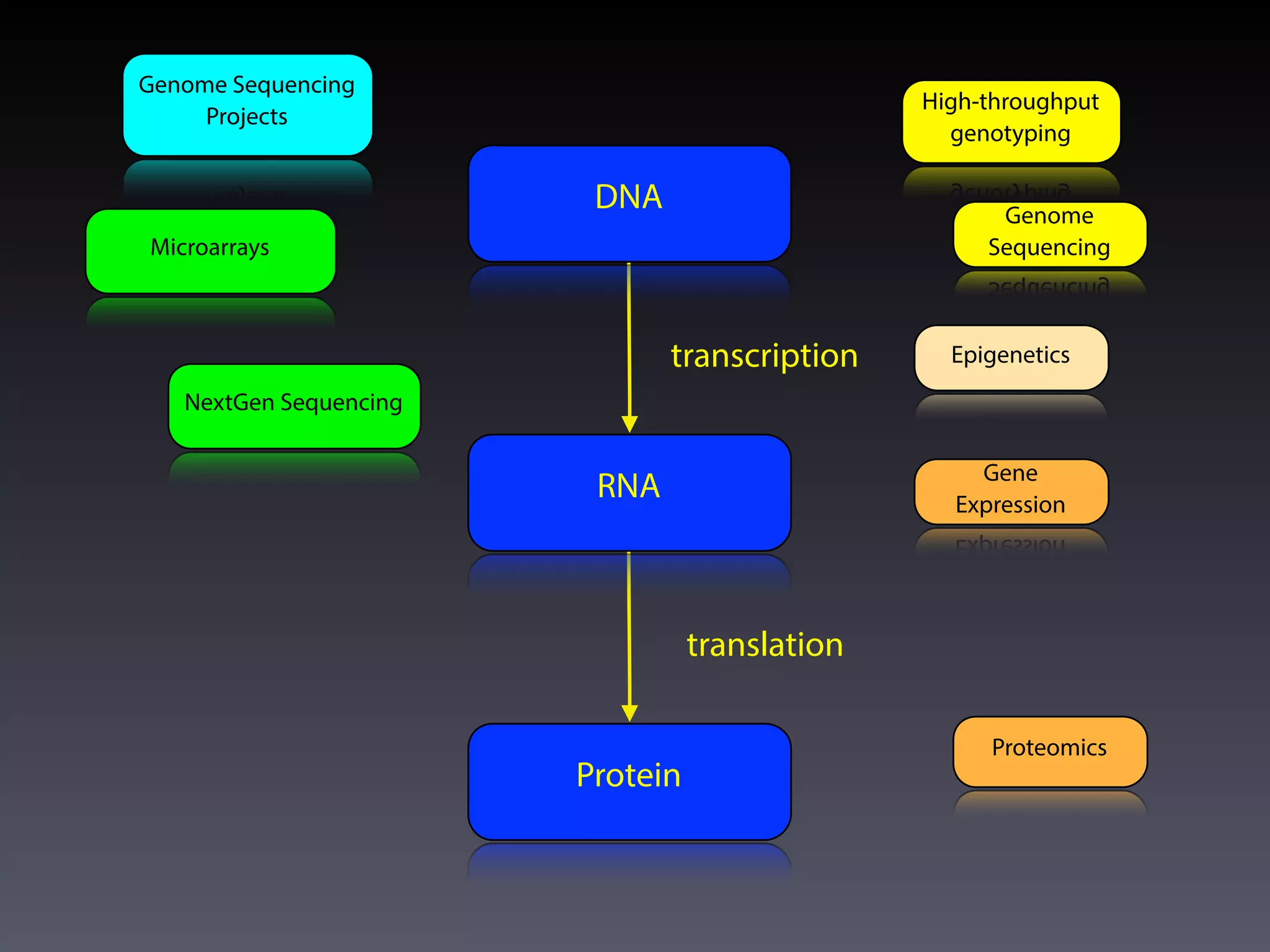

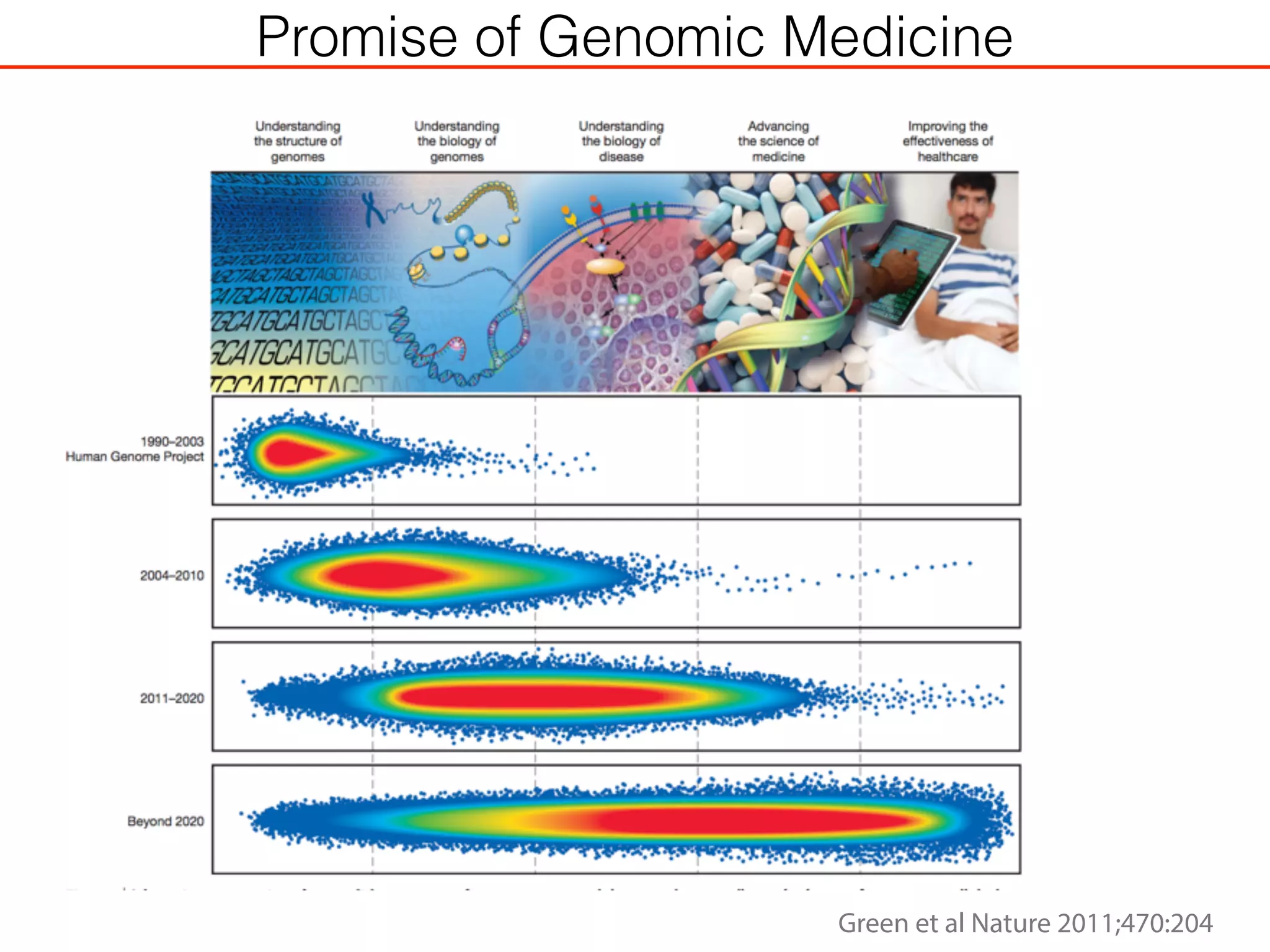

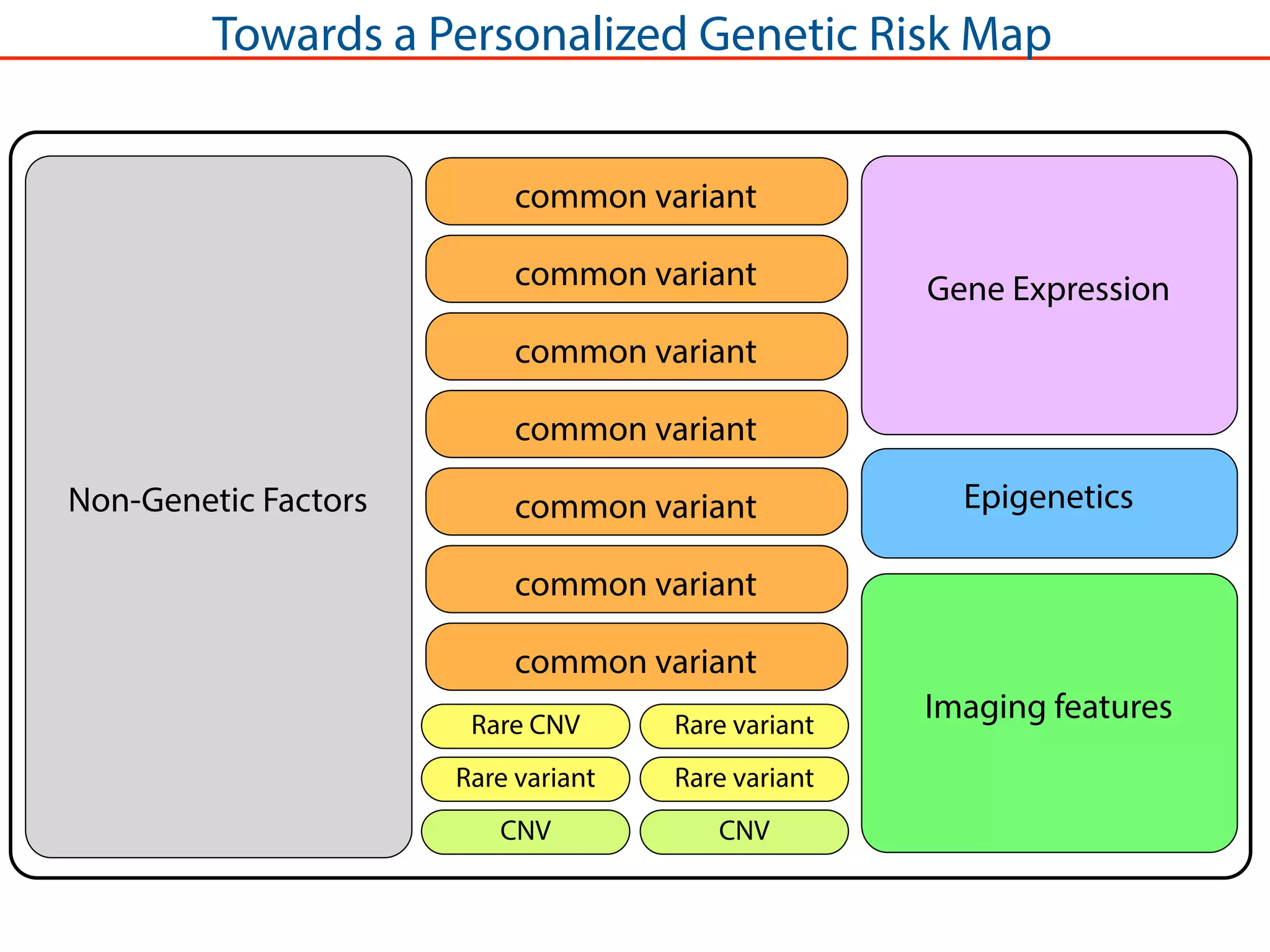

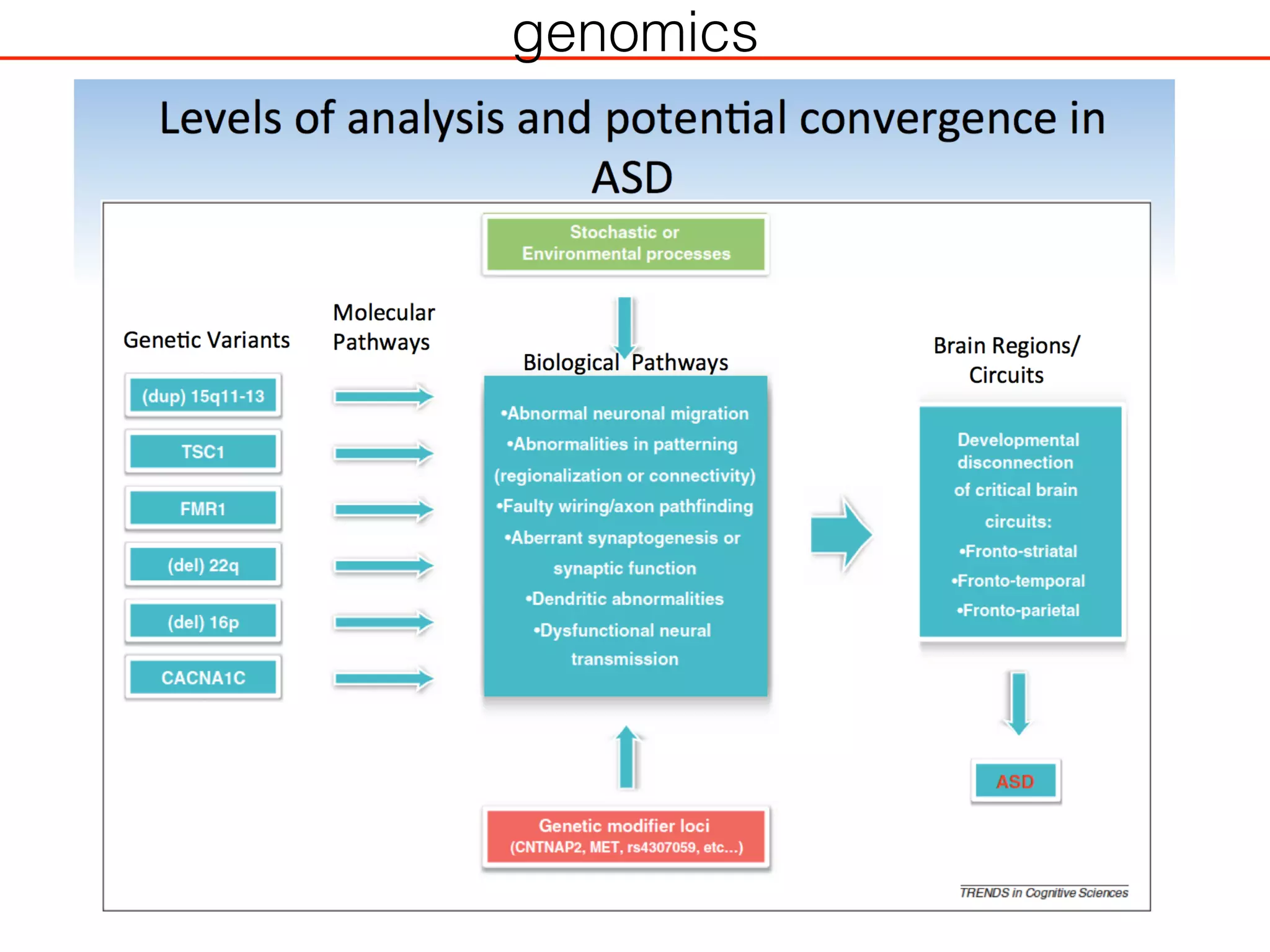

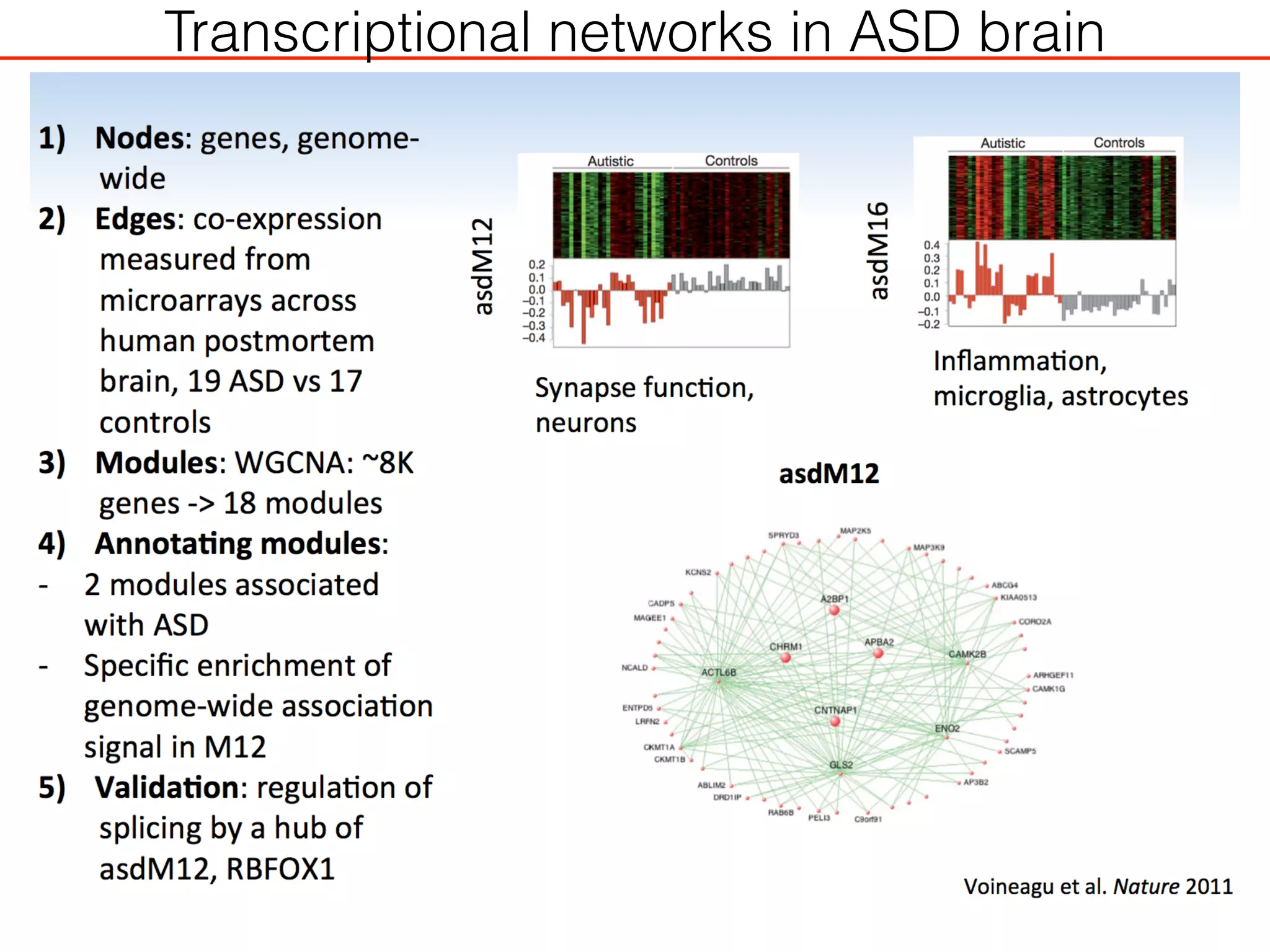

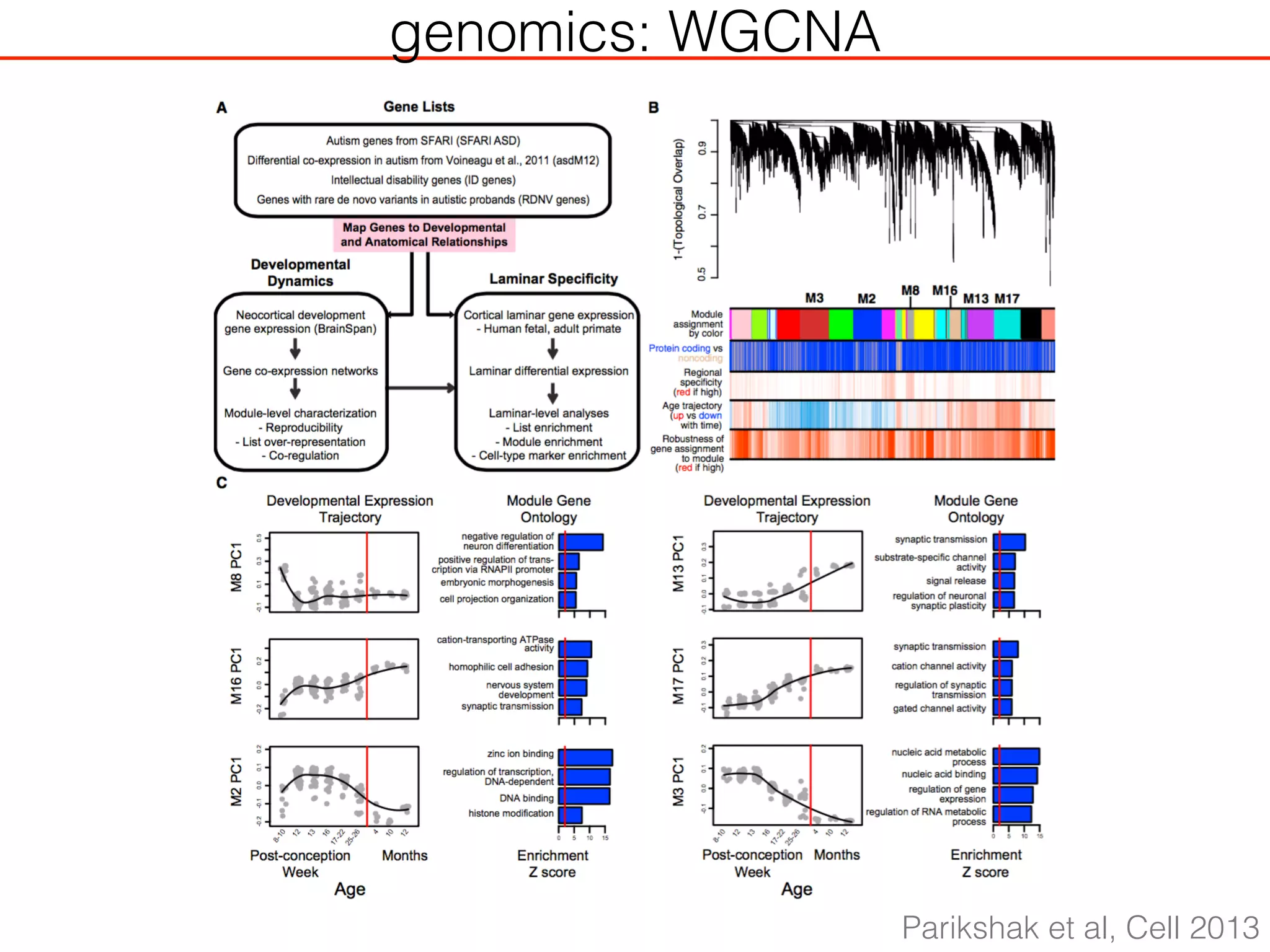

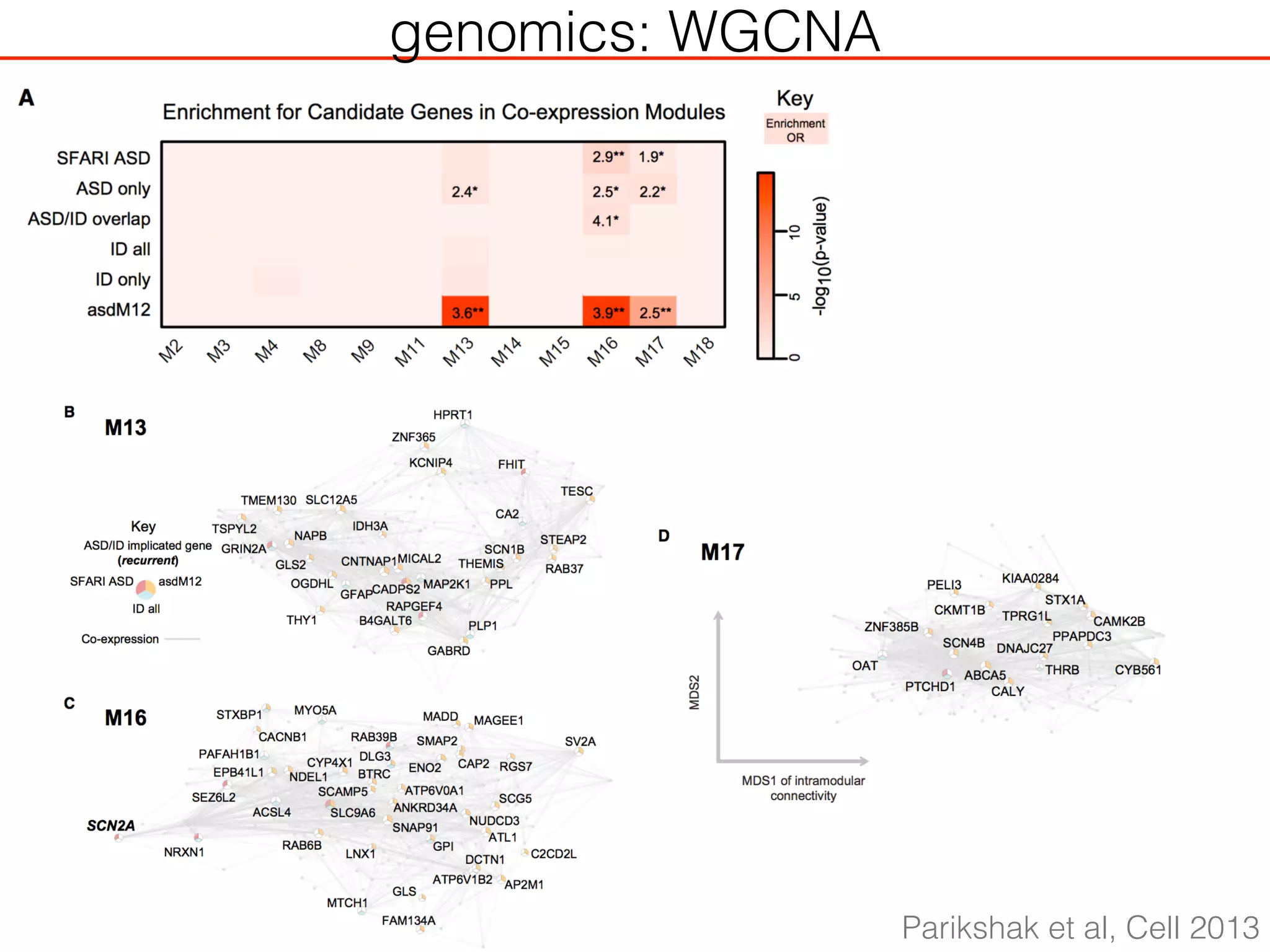

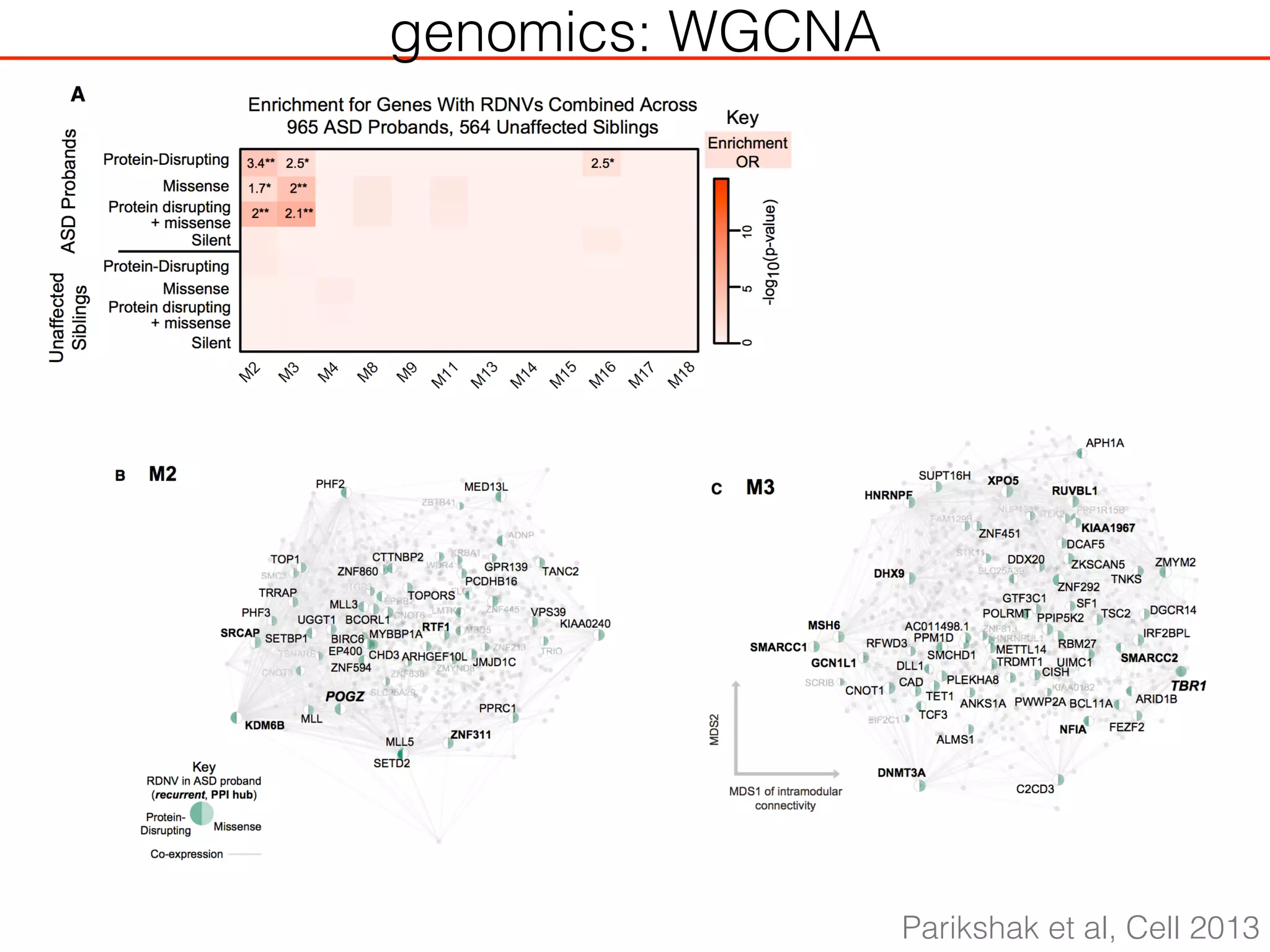

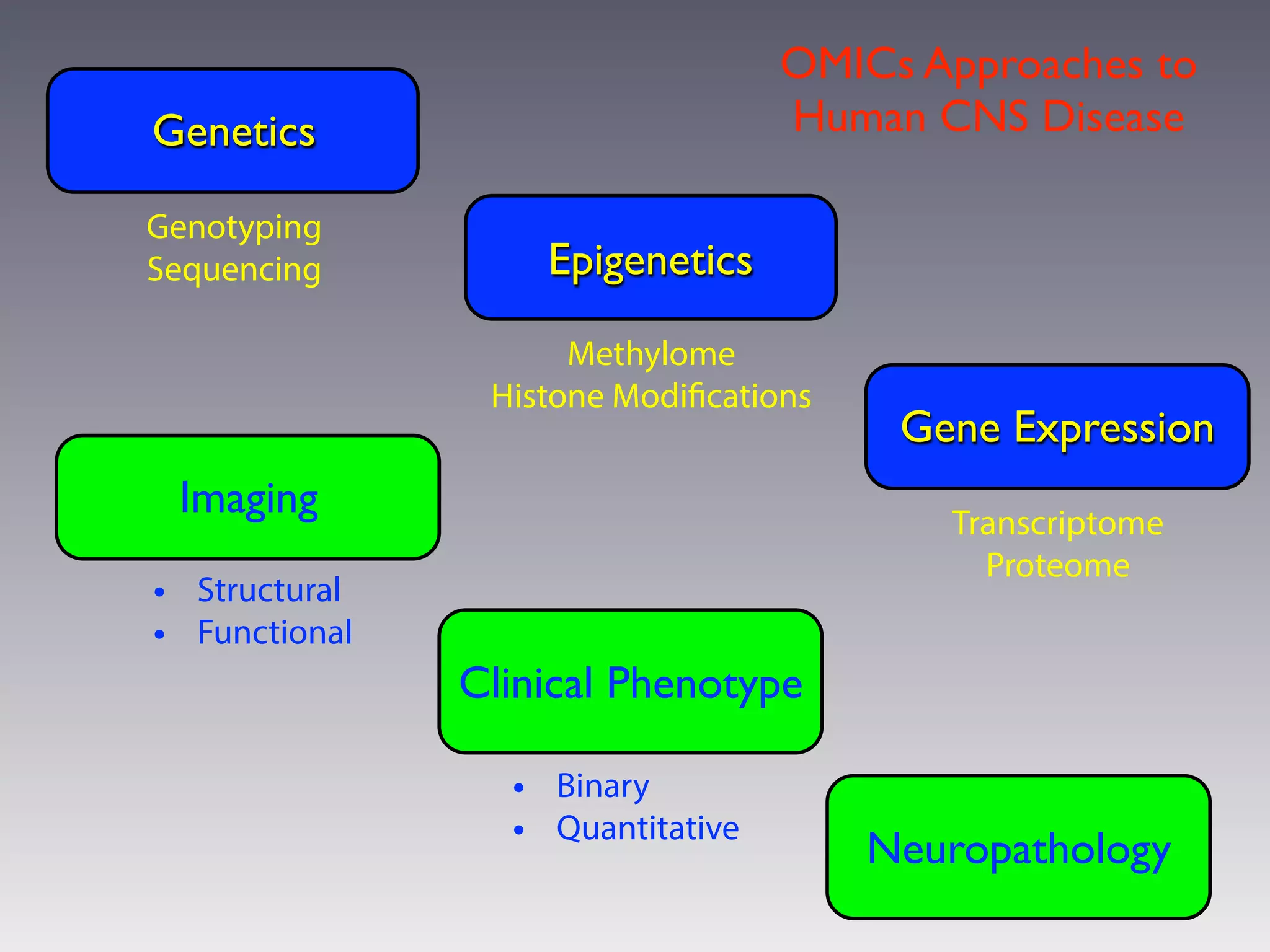

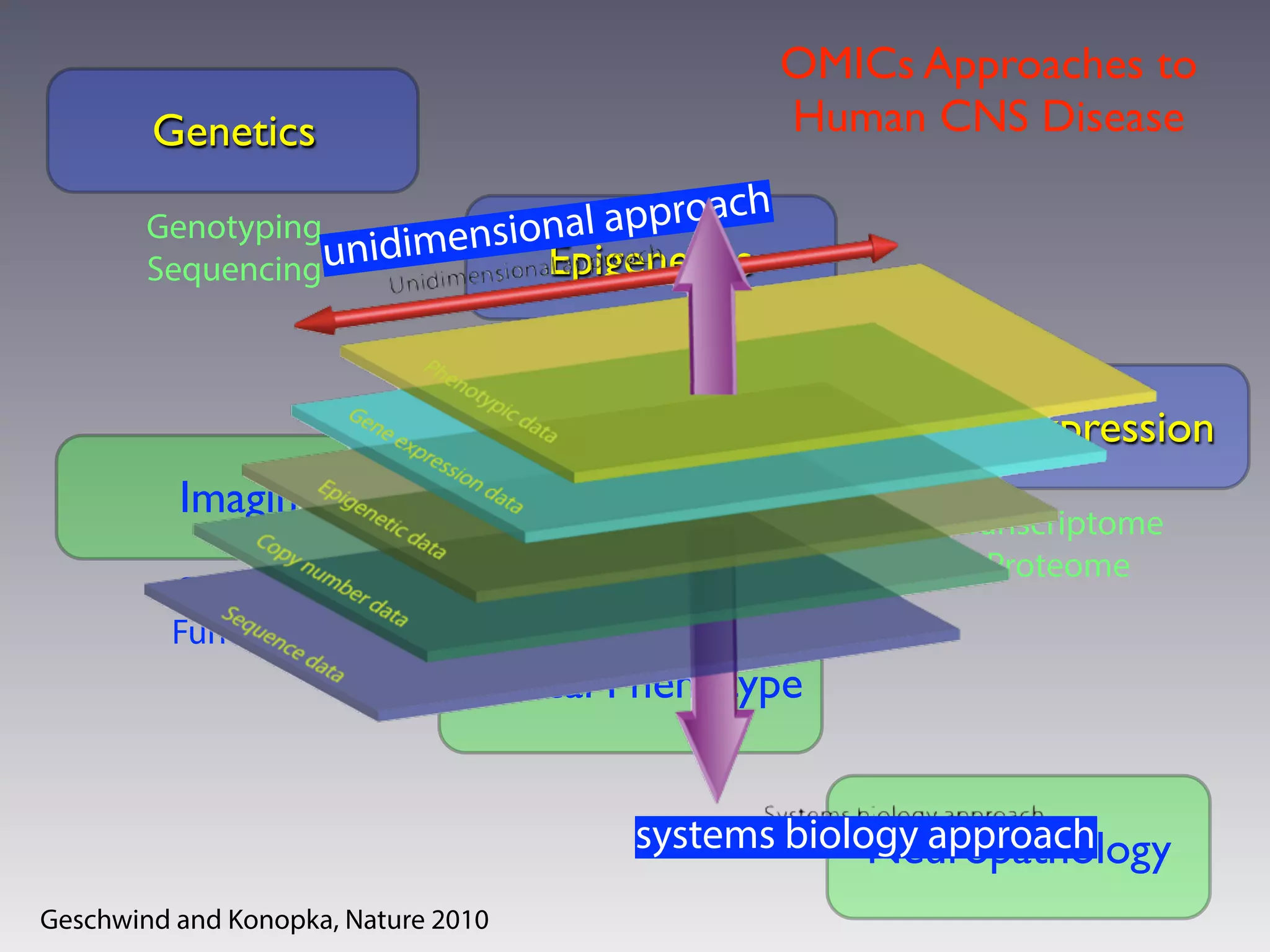

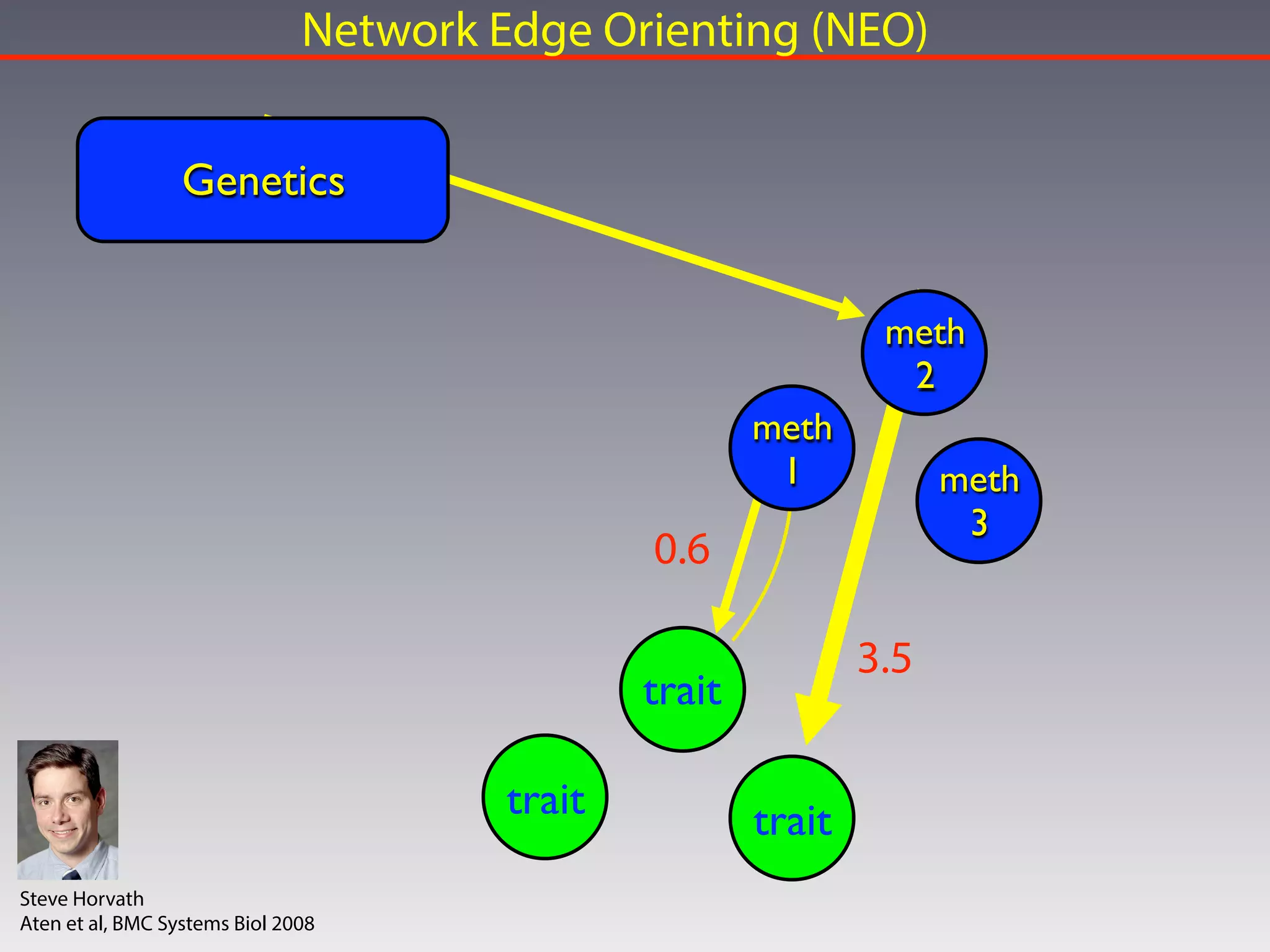

This document outlines an overview of genetic approaches for identifying genes involved in brain development and developmental disorders. It discusses key concepts such as phenotypes and heritability. It covers identifying Mendelian genes, common risk variants identified through genome-wide association studies, and rare variants including rare copy number variants implicated in these disorders. The goal is to elucidate the genetic architecture involving hundreds of common and rare variants contributing to conditions like autism spectrum disorder.