This document is a doctoral thesis submitted by Dein Vindigni to the University of Newcastle for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in October 2004. The thesis examines the musculoskeletal health of Indigenous Australians living in rural communities. It acknowledges the supervision team and expresses gratitude to the Indigenous community, cultural elders, and others who supported the research. The thesis contains 7 chapters that review the burden of musculoskeletal conditions, associated risk factors, opportunities and barriers to management, and a pilot training program for Aboriginal Health Workers to address musculoskeletal health in the community.

![- Prologue - 20

What are the guiding principles of Health Promotion?

The guiding principles of this thesis were drawn from health promotion theory,

which advocates that programs are more likely to be successful when the

modifiable determinants of the health problem are well understood, and the

needs and motivations of the target community are acknowledged and

addressed (Sanson-Fisher & Campbell, 1994; Nutbeam & Harris, 2002). Health

promotion has been defined as:

‘The process of enabling people to increase control over, and

to improve, their health. To reach a state of complete physical,

mental and social well being an individual must be able to

identify and realise aspirations, to satisfy needs and to change

or cope with the environment’

(World Health Organisation [WHO], 1986).

Defining the problem by identifying the magnitude of the health condition(s)

often involves drawing on epidemiological and demographic information as well

as an understanding of the Communities’ needs and priorities. According to

health promotion theory, the nature and quality of available evidence act as a

guide for the choice and design of health promotion activity. Where sufficient

evidence is not available, or the evidence is of poor quality, the researcher is

required to gain data to offset the identified deficiency in evidence (Tugwell et

al., 1985; Hawe, Degeling & Hall, 1990; Green & Kreuter, 1991; Wiggers &

Sanson-Fisher, 1998).

It is now well recognised that the ability of individuals to achieve positive health

outcomes can be significantly increased by enhancing the competence of the

community in which they live to address the broader health issues (Nutbeam &

Harris, 2002). Applying health promotion frameworks when planning an

intervention with community members can assist in comprehensive planning

through identifying options, predicting issues of potential importance, selecting

appropriate options, and explaining difficulties that frequently arise in practice

(Nutbeam & Harris, 2002). Figure 6 outlines the steps towards promoting the

musculoskeletal health of Indigenous people living in rural Communities using a](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thesis-130609031900-phpapp02/85/Thesis-39-320.jpg)

![- Synopsis - 27

(AHWs) who participated in the MTP. This project was a collaborative initiative

between the Durri Aboriginal Medical Service (AMS), Booroongen Djugun

Aboriginal Health College and the School of Medical Practice and Population

Health, Faculty of Health, The University of Newcastle. The collaborative nature

of this initiative was in response to current thinking in Indigenous health, that the

drive and direction for changes to Aboriginal health must come from within

Aboriginal Communities (Houston & Legge, 1992).

The guidelines prepared by the National Health and Medical Research Council

(NH&MRC, 1999) on ethical matters in Aboriginal research were consulted

throughout the development of the survey, clinical assessment, data collection

and intervention phases of the project. In accordance with these guidelines,

AHWs were recruited from the participating Community (NH&MRC, 1999), and

were trained and employed under the auspices of the AMS. Ethics approval to

undertake all aspects of the studies reported in this thesis was obtained from

three sources: Community representatives (via the Durri AMS Board of

Management); the Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) of The

University of Newcastle; and on an individual basis from participating

Community members.

Chapter one of this thesis provides a definition of the musculoskeletal

conditions under investigation. The focus is on musculoskeletal conditions of

mechanical causes (such as osteoarthritis [OA]) and non-specific origin, as

these have been described as the most significant causes of pain and disability

(Volinn, 1997). This chapter broadly explores the implications of

musculoskeletal conditions in terms of the physical, emotional and economic

burdens they impose. Indigenous people are the focus of this thesis because of

their poor health status in Australia. Although they experience poor health in

general, this includes health burdens associated with musculoskeletal

conditions. Indigenous people living in rural Communities are the particular

focus due to the evident health disadvantage in these Communities (McLennan

& Madden, 1999) and because a substantial proportion of Indigenous

Australians live in rural regions (ABS 1998a).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thesis-130609031900-phpapp02/85/Thesis-46-320.jpg)

![- Chapter five - 190

5.3.8 Analyses

Analyses of demographic data (including Age, Gender, Occupation, Marital

status) and physical characteristics (Weight, Height, Body Mass Index [BMI])

were used to describe the sample, and explore if the sample obtained was

consistent with previous census findings (Huntington, 2000).

Frequencies were tabulated for Report of musculoskeletal conditions, Body site,

Duration of symptoms, Number of conditions, reported Pain, reported Limitation,

Risk factors and Management of conditions. Data pertaining to reported levels

of Pain, Limitation attributable to the reported Pain, Duration of symptoms,

Number of conditions, Risk factors and Management were grouped into

categories to facilitate comparative analyses.

Chi square analyses (Greenberg et al., 1993) were used to test associations

between musculoskeletal conditions (including Pain, Limitation, Duration of

symptoms, Number of conditions) and factors such as demographic and

physical characteristics, Occupational risk factors, Obesity, Physical inactivity

and Trauma.

While Marital status included ‘Never married’, ‘Married’, ‘De Facto’, ‘Separated’,

‘Divorced’ and ‘Widowed’, these categories were grouped as necessary into

‘Married/De facto’ and ‘No Partner’, to allow for more meaningful comparisons

given the small numbers in each sub-category.

Reported high Pain levels were further examined specifically within the sub-

categories of the most prevalent conditions in the Community including LBP,

neck and shoulder pain. High pain levels were classified as scores greater than

7/10 on a 10-point Likert scale and Low levels were classified as scores less

than 5/10 on the Likert scale.

Reported Limitation was examined within the sub-categories of the most

prevalent conditions. High limitation levels were classified as scores greater

than 6/10 and Low levels as scores less than 5/10 on a Likert 10-point scale.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thesis-130609031900-phpapp02/85/Thesis-209-320.jpg)

![- References - 2

Prologue

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2002). Deaths 2001. Catalogue No. 3302.0.

Canberra, ABS.

Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council Standing Committee for Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander Health. (2002). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

health workforce national strategic framework. [Canberra], Australian Health

Ministers' Advisory Council: ii, 21.

Buchanan N (2001). Interview with Dein Vindigni on ‘the history of the Dunghutti

Nation since European settlement and beyond’. Interview in Kempsey, NSW,

July 2001.

Cook DJ, Greengold NL, Ellrodt AG, Weingarten SR (1997). The relation

between systematic reviews and practice guidelines. Ann Intern Med 127(3):

210-6.

Couzos S, Murray R, Kimberley Aboriginal Medical Services Council (WA)

(1999). Aboriginal primary health care: an evidence-based approach.

Melbourne, Vic., Oxford University Press.

Durie MH (2003). The health of indigenous peoples. BMJ 326(7388): 510-1.

Gordon P (1998). Interview with Dein Vindigni on ‘The history of Brewarrina’,

NSW, July, 1998.

Green L, Kreuter M (1991). Health Promotion Planning: An Educational and

Environmental Approach. Mountain View CA, Mayfield Publishing Company.

Hawe P, Degeling D, Hall J (1990). Evaluating health promotion: a health

worker's guide. Sydney, MacLennan & Petty.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thesis-130609031900-phpapp02/85/Thesis-331-320.jpg)

![- References - 6

Synopsis

Australian Bureau of Statistics (1998a). 1996 census population and housing:

community profiles for Australia. Cat. No. 2020.0. Canberra, ABS.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (1998b). Experimental estimates of the

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population, 30 June 1991 - 30 June 1996.

[Canberra], Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Donovan RJ, Spark R (1997). Towards guidelines for survey research in remote

Aboriginal Communities. Aust N Z J Public Health 21(1): 89-95.

Durie MH (2003). The health of indigenous peoples. BMJ 326(7388): 510-1.

Dwyer AP (1987). Backache and its prevention. Clin Orthop (222): 35-43.

Gordon P (1998). Interview with Dein Vindigni on ‘The history of Brewarrina’,

NSW, July, 1998.

Green L, Kreuter M. Health Promotion Planning. An Educational and

Environmental Approach. Second Edition. Mayfield Publishing Company,

Mountain View, Toronto, London, 1991.

Houston S, Legge D (1992). Aboriginal health research and the National

Aboriginal Health Strategy. Aust J Public Health 16(2): 114-5.

Li'Dthia Warrawee'a K (2000). An aboriginal perspective on holistic health.

Diversity, Natural & Complementary Health 2(2): 2-9.

McLennan W, Madden R (1999). The Health and Welfare of Australia’s

Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander Peoples. Canberra, Australian Bureau of

Statistics & the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, ABS Catalogue no.

4704.00 AIHW Catalogue no. IHW 3.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thesis-130609031900-phpapp02/85/Thesis-335-320.jpg)

![- References - 8

Chapter one

Aaronson NK, Muller M, Cohen PD, et al. (1998). Translation, validation, and

forming of the Dutch language version of the SF-36 Health Survey in community

and chronic disease populations. J Clin Epidemiol 51(11): 1055-68.

Adams MA, Mannion AF, Dolan P (1999). Personal risk factors for first-time low

back pain. Spine 24(23): 2497-505.

Anderson RT (1984). An orthopaedic ethnography in rural Nepal. Medical

Anthropology 8(1): 46-59.

Andersson G (1997). The epidemiology of spinal disorders. In: Frymoyer JW

(ed). The adult spine: principles and practice. Philadelphia, PA, Lippincott-

Raven: 93-141.

Australian Acute Musculoskeletal Pain Guidelines Group (AAMPG) (2003).

Evidence-based management of acute musculoskeletal pain [Online. Available

at http://www.nhmrc.gov.au ]. Australian Academic Press: Brisbane.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (1995). National Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander survey 1994: detailed findings. Canberra, Australian Bureau of

Statistics, Cat. No. 4190.0.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (1998). 1996 census population and housing:

community profiles for Australia. Cat. No. 2020.0. Canberra, ABS.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (1999). National Health Survey: Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander Results, 1995, Cat. No. 4806.0, ABS, Canberra.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2002). Deaths 2001. Catalogue No 3302.0.

Canberra, ABS.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thesis-130609031900-phpapp02/85/Thesis-337-320.jpg)

![- References - 9

Australian Health Infonet (2003). Summary of Indigenous health: hospitalisation.

Available at: www.healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au (Accessed 27 August, 2003).

Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council Standing Committee for Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander Health. (2002). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

health workforce national strategic framework. [Canberra], Australian Health

Ministers' Advisory Council:

ii, 21.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (1997). Australia’s Welfare. Cat. No.

AUS 8. Canberra, Australian Government Publishing Service.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2000). Australia's Health 2000: the

seventh biennial health report of the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Canberra: AIHW.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2002a). Australia’s Health 2002: the

eighth biennial health report of the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Canberra, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2002b). Health system costs of

injury, poisoning and musculoskeletal disorders in Australia 1993-94. Available

at: www.aihw.gov.au (Accessed July 29 2003). Canberra, Australian

Government Publishing Service.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Britt H, Miller G, Charles J, et al.

(2000). General practice activity in Australia 1999-00. General Practice Series

No. 5. AIHW Cat. No. GEP 5. Canberra: AIHGW GPSCU.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Mathers C & Penm R (1999). Health

system costs of injury, poisoning and musculoskeletal disorders in Australia

1993-94. Health and Welfare Expenditure Series No 6. AIHW Cat. No. HWE 12

Canberra: AIHW.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thesis-130609031900-phpapp02/85/Thesis-338-320.jpg)

![- References - 10

Barnsley L, Lord S, Bogduk N (1993). The pathophysiology of whiplash. Spine:

state of the art reviews 7: 329-53.

Becker N, Bondegaard Thomsen A, Olsen AK, et al. (1997). Pain epidemiology

and health related quality of life in chronic non-malignant pain patients referred

to a Danish multidisciplinary pain center. Pain 73(3): 393-400.

Berkow R (1992). Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy, Chapter 11

Neurological Disorders. Sixteenth Edition, Merck & Co., New Jersey, USA,

1380-1526.

Biering-Sorensen F (1982). Low back trouble in a general population of 30-, 40-,

50-, and 60-year-old men and women. Study design, representativeness and

basic results. Danish Medical Bulletin 29(6): 289-99.

Black K, Eckerman S (1997). Disability support services provided under the

Commonwealth/State Disability Agreement: first national data 1995. Canberra

AIHW.

Boreham P, Whitehouse G, Harley B (1993). The labour force status of

Aboriginal people: a regional comparison. Labour and Industry 5(1): 16-32.

Boudreau LA, Reitav J (2001). Psychosocial and physical factors in work

transition leading to musculoskeletal pain. Journal of the Neuro

musculoskeletal System 9(4): 129-34.

Bowling A (1997). The Conceptualization of Functioning, Health and Quality of

Life. Pg 1-3. In: Bowling A. Measuring health. A review of quality of life

measurement scales. 2nd Ed. Buckingham, Philadelphia, Open University

Press.

Britt H (1994). Patient reasons for encounter in general practice in Australia.

[Thesis] University of Sydney.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thesis-130609031900-phpapp02/85/Thesis-339-320.jpg)

![- References - 15

Lawrence RC, Everett DF, Benevolenskaya LI, et al. (1996).

Spondyloarthropathies in circumpolar populations: I. Design and methods of

United States and Russian studies. Arctic Medical Research. 55(4): 187-94.

Leboeuf-Yde C & Lauritsen JM (1995). The prevlance of low back pain in the

literature. A structured review of 26 Nordic studies from 1954 to 1993. Spine.

20(19): 2112-8

Lee TG (1998). Indigenous Health. A Needs Assessment Study of the Outer

Eastern Metropolitan Region of Melbourne. Detailed Report. Victoria, Yarra

Ranges Health Service.

Lehoczky, et al. (2002). Hospital statistics. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

Australians. 1999-2000. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Levy E, Ferme A, Perocheau D, Bono I (1993). [Socioeconomic costs of

osteoarthritis in France]. Revue du Rhumatisme. Edition Francaise 60(6 Pt 2):

63S-7S.

Loney PL, Stratford PW (1999). The prevalence of low back pain in adults: a

methodological review of the literature. Physical Therapy 79(4): 384-96.

March LM, Bachmeier CJ (1997). Economics of osteoarthritis: a global

perspective. Baillieres Clinical Rheumatology 11(4): 817-34.

Mathers C, Vos T, Stevenson C (1999). The burden of disease and injury in

Australia. Canberra, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, AIHW Catalogue

No. PHE 17.

Matsui H, Maeda A, Tsuji H, Naruse Y (1997). Risk indicators of low back pain

among workers in Japan. Association of familial and physical factors with low

back pain. Spine 22(11): 1242-7; Discussion 8.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thesis-130609031900-phpapp02/85/Thesis-344-320.jpg)

![- References - 24

Chapter three

Royal Society, New South Wales, 1889, xxiii, p.491. Cited in: Basedow H. The

Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, p.230, August 1st, 1932.

Australian Wild Herb Bulletin, September 2000, Volume 2, Issue 3, p.1-7.

Aagaard-Hansen J, Saval P, Steino P, Storr-Paulsen A (1991). [Back health of

students]. Nord Med 106(3): 80-1.

Aagaard-Hansen J, Storr-Paulsen AA (1995). A comparative study of three

different kinds of school furniture. Ergonomics 38(5): 1025-35.

Adams MA, Mannion AF, Dolan P (1999). Personal risk factors for first-time low

back pain. Spine 24(23): 2497-505.

Alcouffe J, Manillier P, Brehier M, Fabin C, Faupin F (1999). Analysis by sex of

low back pain among workers from small companies in the Paris area: severity

and occupational consequences. Occup Environ Med 56(10): 696-701.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (1995). National Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander survey 1994: detailed findings. Canberra, Australian Bureau of

Statistics.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Health system costs of injury,

poisoning and musculoskeletal disorders in Australia 1993-94. Published,

1995. Available at: www.aihw.gov.au (Accessed July 29, 2003).

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2002a). Australia's Health 2002: the

eighth biennial health report of the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Canberra, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thesis-130609031900-phpapp02/85/Thesis-353-320.jpg)

![- References - 37

Papageorgiou AC, Macfarlane GJ, Thomas E, et al. (1997). Psychosocial

factors in the workplace-do they predict new episodes of low back pain?

Evidence from the South Manchester Back Pain Study. Spine 22(10): 1137-42.

Pope MH, Wilder DG, Magnusson ML (1999). A review of studies on seated

whole body vibration and low back pain. Proc Inst Mech Eng [H] 213(6): 435-46.

Preyde M (2000). Effectiveness of massage therapy for subacute low-back

pain: a randomised controlled trial. CMAJ 162(13): 1815-20.

Riihimaki H, Viikari-Juntura E, Moneta G, et al. (1994). Incidence of sciatic pain

among men in machine operating, dynamic physical work, and sedentary work.

A three-year follow-up. Spine 19(2): 138-42.

Roquelaure Y, Mechali S, Dano C, et al. (1997). Occupational and personal risk

factors for carpal tunnel syndrome in industrial workers. Scand J Work Environ

Health 23(5): 364-9.

Ryden LA, Molgaard CA, Bobbitt S, Conway J (1989). Occupational low-back

injury in a hospital employee population: an epidemiologic analysis of multiple

risk factors of a high-risk occupational group. Spine 14(3): 315-20.

Saggers S, Gray D (1991). Aboriginal Health and Society: the traditional and

contemporary Aboriginal struggle for Better Health. Sydney, Allen and Unwin.

Salminen JJ (1984). The adolescent back. A field survey of 370 Finnish

schoolchildren. Acta Paediatr Scand Suppl 315: 1-122.

Salminen J, Pentti J, Terho P (1992). Low back pain and disability in 14-year-

old schoolchildren. Abstracts of the Third International Congress: Back pain-

current concepts and recent advances, Scandinavia.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thesis-130609031900-phpapp02/85/Thesis-366-320.jpg)

![- References - 38

Salminen JJ, Maki P, Oksanen A, Pentti J (1992). Spinal mobility and trunk

muscle strength in 15-year-old schoolchildren with and without low-back pain.

Spine 17(4): 405-11.

Schonstein E, Kenny DT, Keating J, Koes BW (2003). Work conditioning, work

hardening and functional restoration for workers with back and neck pain

(Cochrane Review). The Cochrane Library, Issue 3. Oxford: Updated Software.

Scutter S, Turker KS, Hall R (1997). Headaches and neck pain in farmers.

Australian Journal of Rural Health. 5(1): 2-5.

Snook SH (1988). Approaches to the control of back pain in industry: job

design, job placement and education/training. Occup Med 3(1): 45-59.

Storr-Paulsen AA (1995). A comparative study of three different kinds of school

furniture. Ergonomics 38(5): 1025-35.

Taplin Rev (1875). Report Sub-Protector Aborigines, South Australia,

December, p.6.

Thomson N, Paterson B. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health

bibliography. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health

Clearinghouse, Dept. of Health Studies, Edith Cowan University, Joondalup,

WA. Availabe at: http://www.healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au (Accessed November

12, 2003].

Towheed TE, Anastassiades TP, Shea B, et al. (2003). Glucosamine therapy

for treating osteoarthritis (Cochrane Review). The Cochrane Library, Issue 3.

Oxford: Updated Software.

Troussier B, Davoine P, de Gaudemaris R, Fauconnier J, Phelip X (1994). Back

pain in school children. A study among 1178 pupils. Scand J Rehabil Med

26(3): 143-6.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thesis-130609031900-phpapp02/85/Thesis-367-320.jpg)

![- References - 40

Westhof E, Ernst E (1992). [The history of massage] Dtsch Med Wochenschr;

117(4):150-153.

Wiggers J, Sanson-Fisher R (1998). Evidence-based health promotion. In:

Scott, D and Weston, R. Evaluating Health Promotion. London, Stanley Thornes

Ltd.

Wigley R, Manahan L, Muirden KD, et al. (1991). Rheumatic disease in a

Philippine village. II: a WHO-ILAR-APLAR COPCORD study, phases II and III.

Rheumatology International. 11(4-5): 157-61.

Wigley RD, Zhang NZ, Zeng QY, et al. (1994). Rheumatic diseases in China:

ILAR-China study comparing the prevalence of rheumatic symptoms in northern

and southern rural populations. Journal of Rheumatology. 21(8): 1484-90.

Wiley DC, James G, Jonas J, Crosman ED (1991). Comprehensive school

health programs in Texas public schools. J Sch Health 61(10): 421-5.

Williams K (1999). [Back pain]. Ugeskr Laeger 161(3): 273-4.

World Health Organisation (1996). Regional guidelines. Development of health

promoting schools - a framework for action. Geneva, World Health

Organisation.

World Health Organisation (2003). Scientific Group on the Burden of

Musculoskeletal Conditions at the Start of the New Millennium. 2003: Geneva,

Switzerland.

Yeung EW, Yeung SS (2003). Interventions for preventing lower limb soft-tissue

injuries in runners (Cochrane Review). The Cochrane Library, Issue 3. Oxford:

Updated Software.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thesis-130609031900-phpapp02/85/Thesis-369-320.jpg)

![- References - 41

Chapter four

Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council, Australian Health Ministers'

Advisory Council. Standing Committee for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

Health. (2002). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workforce National

Strategic Framework. [Canberra], Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council:

ii, 21.

Guidelines for Chiropractic Quality Assurance and Practice Parameters (Mercy

Guidelines). Editors: Haldeman S, Chapman-Smith D, Petersen DM.

Consensus Conference Commissioned by the Congress of Chiropractic State

Associations. Mercy Conference Center, Burlingame, California, USA (1992).

Bolton JE (1999). Accuracy of recall of usual pain intensity in back pain

patients. Pain 83(3): 533-9.

Bolton JE, Breen AC (1999). The Bournemouth Questionnaire: a short-form

comprehensive outcome measure. I. Psychometric properties in back pain

patients. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 22(8): 503-10.

Canadian Chiropractic Association (1993). Clinical Guidelines for Chiropractic

Practice in Canada. Editors: Henderson D, Chapman-Smith D, Silvano M,

Vernon H. Proceedings of a Consensus Conference Commissioned by the

Canadian Chiropractic Association. Glenerin Inn, Mississauga, Ontario,

Canada.

Cardiel MH (1993). Rheumatic diseases in Mexico: Validation of the

ILAR/COPCORD core questionnaire against physical exam. XVIII ILAR

Congress of Rheumatology, Barcelona, Spain, Published in: Rev Esp.

Rheumatol, Vol 20, Supp 1.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thesis-130609031900-phpapp02/85/Thesis-370-320.jpg)

![- References - 46

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (1998b). Experimental estimates of the

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population, 30 June 1991 - 30 June 1996.

[Canberra], Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council., Australian Health Ministers'

Advisory Council, Standing Committee for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

Health. (2002). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workforce National

Strategic Framework. [Canberra], Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (1992). Australia’s Health 1992. The

Third Biennial Report of the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Canberra, Australian Government Publishing Service.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2002a). Australia's Health 2002 : the

eighth biennial health report of the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Canberra, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2002b). Health system costs of

injury, poisoning and musculoskeletal disorders in Australia 1993-94. Available

at: www.aihw.gov.au (Accessed July 29, 2003). Canberra, Australian

Government Publishing Service.

Becker N, Bondegaard Thomsen A, Olsen AK, et al. (1997). Pain epidemiology

and health related quality of life in chronic non-malignant pain patients referred

to a Danish multidisciplinary pain center. Pain 73(3): 393-400.

Bolton JE (1999). Accuracy of recall of usual pain intensity in back pain

patients. Pain 83(3): 533-9.

Bolton JE, Breen AC (1999). The Bournemouth Questionnaire: a short-form

comprehensive outcome measure. I. Psychometric properties in back pain

patients. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 22(8): 503-10.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thesis-130609031900-phpapp02/85/Thesis-375-320.jpg)

![- References - 55

Chapter six

Aboriginal Healthinfonet. Available at: www.healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au

(Accessed: July 30, 2003).

Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council, Australian Health Ministers'

Advisory Council. Standing Committee for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

Health. (2002). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workforce National

Strategic Framework. [Canberra], Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council:

ii, 21.

Australian National Training Authority (ANTA) Available at:

http://www.anta.gov.au/dapStrategies.asp (Accessed: February 10, 2002).

National Training Information Service (NTIS), Community Services and Health

Industry Council, Australian National Training Authority, 2002.

Available at: http://www.ntis.gov.au (Accessed: August 19, 2004).

Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. Canberra: Australian

Government Publishing Service. (1992).

Training Revisions. National Review of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

Health Worker Training. A report submitted to the Office for Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander Health. (2002). Curtin Indigenous Research Centre with

Centre for Education Research and Evaluation Consortium and Jojara &

Associates.

Browell T (2003). Founder and Principal, Murray School of Health Education,

Established 1979. Echuca, Mildura, Victoria.

Buchanan N (2002). Listening and learning from each other. Interview with

Indigenous elder Uncle Neville Buchanan and Dein Vindigni, Booroongen

Djugun College, Kempsey, NSW. July 2002.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thesis-130609031900-phpapp02/85/Thesis-384-320.jpg)

![- References - 59

Chapter seven

Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council, Australian Health Ministers'

Advisory Council. Standing Committee for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

Health. (2002). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workforce National

Strategic Framework. [Canberra], Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2002). Australia's Health 2002 : the

eighth biennial health report of the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Canberra, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Bolton JE, Breen AC (1999). The Bournemouth Questionnaire: a short-form

comprehensive outcome measure. I. Psychometric properties in back pain

patients. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 22(8): 503-10.

Bolton JE (1999). Accuracy of recall of usual pain intensity in back pain

patients. Pain 83(3): 533-9.

Bourke C, Bourke E, Edwards B, (Eds) (2003). Aboriginal Australia. An

Introductory reader in Aboriginal Studies. Queensland. University of

Queensland Press.

Darmawan J, Valkenburg HA, Muirden KD, Wigley RD (1992). Epidemiology of

rheumatic diseases in rural and urban populations in Indonesia: a World Health

Organisation International League Against Rheumatism COPCORD study,

stage I, phase 2. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 51(4): 525-8.

Davis G, Wanna J, Warhurst J, Weller P (1988). Public policy in Australia. Allen

and Unwin, Sydney.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thesis-130609031900-phpapp02/85/Thesis-388-320.jpg)

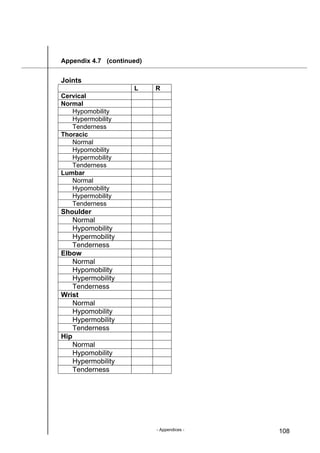

![- Appendices - 105

Appendix 4.7 Participant Assessment Form (revised)

Participant Assessment Form (revised)

Kempsey Pilot Program

Survey date: ____/____/____ Investigator/s: ______________________

Name/code number: _______________

Date of Birth: ____/____/____

Gender: _______

Height: _______ [cm]

Weight: _______ [Kg

Occupation:

Yes No

Aged pensioner

Disability pensioner

Management

CDEP students

TAFE & High School

Health worker

Home duties

Labourers

Clerical

Professional

Other

Marital status:

Yes No

Married

De-facto

Separated

Divorced

Widowed

Never married

Number of children: _______](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thesis-130609031900-phpapp02/85/Thesis-434-320.jpg)

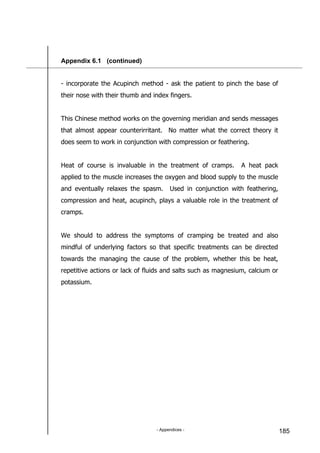

![- Appendices - 106

Appendix 4.7 (continued)

Vital signs

Blood pressure: _______ [mmHg]

Pulse rate: ___________ [bpm]

Respiration rate: _______ [rpm]

Temperature: _________ [°C]

Musculoskeletal Assessment

Inspection

Posture

Yes No

Forward head carriage

Normal thoracic kyphosis

Increased thoracic kyphosis

Decreased thoracic kyphosis

Normal lumbar lordosis

Increased lumbar lordosis

Decreased lumbar lordosis

Scoliosis

Yes No

Cervical

Thoracic

Lumbar

Joint abnormalities

Yes No

Swelling

Reddening

Thickening

Location (of joint abnormalities)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thesis-130609031900-phpapp02/85/Thesis-435-320.jpg)

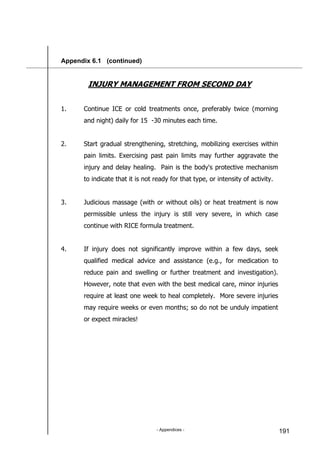

![- Appendices - 217

Appendix 6.1 (continued)

Hopbush, sticky hopbush (common name)

(botanical name: Sapindaceae)

Hopbush is one if the more well-documented indigenous medical herbs.

Details of numerous traditional uses have been accumulated from four

continents including Australia.

Family: Sapindaceae

Description: Erect evergreen shrubs 5m high, may be

monoecious or dioecious. Leaves linear-lanceolate,

narrowly tapered at apex base, entire margins,

glabrous, petiolate, 6-13cm long, 5-10mm wide.

Flowers appear in Spring on pedicels 3-9mm long

arranged in terminal panicles. Sepals 3-4 petals

absent. Capsules, winged with a glabours surface,

cover the plant during summer [Harden, 1991].

Distribution: Dodonea viscose is widespread in Eastern

Australia, and also found in parts of Asia, Africa

and Central America. The subspecies angustifolia

occurs in the Americas, the Asia-Pacific region and

from tropical to southern Africa [Ghisalberti 1998]

as well as eastern Australia where it grows chiefly

on slopes and tablelands in dry sclerophyll forest

or woodland.

Part used: Leaves, aerial parts, roots

Traditional Uses: Hopbush was used by Aborigines in the form of a

root decoction for cuts and open wounds. Leaves

were chewed as a painkiller and used for

toothache. Boiled root juice was applied for

headache [Isaacs, 1987]. In India a tincture](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thesis-130609031900-phpapp02/85/Thesis-546-320.jpg)

![- Appendices - 218

Appendix 6.1 (continued)

was taken internally for gout, rheumatism and

fevers. A poultice of leaves was applied to

painful swellings and rheumatic joints. In Mexico

various preparations were used to treat

inflammation, swellings and pain.

Actions: Spasmolytic anti-inflammatory, andoyne.

Pharmacy research: The spasmolytic effects displayed by D.viscose

were equal to that Datura lanosa, and standard

anticholinergic, a calcium channel blocking

mechanism. Anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant

activity.

Reasearch: Dr. Sean Cox from the Centre for Biomolecular

University of Western Sydney is currently

investigating the antiinflammatory and

antioxidant activity using samples of my 1.4

dried tincture of Dodonaea ssp. Angustifolia leaf.

This data is unpublished.

Indications: Gout rheumatism, inflammatory disorder,

toothache and applied to painful stings [Isaacs,

1987]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thesis-130609031900-phpapp02/85/Thesis-547-320.jpg)