The document outlines steps for conducting effective case analysis, emphasizing a systematic approach that includes examining the overall case, identifying problems, performing qualitative and quantitative analyses, and developing actionable recommendations. It highlights the importance of utilizing various data sources, maintaining an open-minded perspective on evolving interpretations, and understanding the complexity of real-world business situations. Additionally, it discusses the need for thorough action plans addressing short-, medium-, and long-term objectives, with an emphasis on structuring tasks and recognizing the nuances of case dynamics.

![When I joined in 2004, SCF was a mere sum of different units

placed in different countries,

with different business models, operations, IT platforms and

marketing approaches. We

wanted to make it worth more than the sum of the parts. First

we integrated the different

brands. The SCF brand was not known outside of the

[Santander] Group as each affiliated

company maintained its name. We changed their names into

SCF. Secondly, we centralized the

decisions concerning funding, and thirdly we centralized the

customer data centers.

By June 2008, SCF operated in 20 countries. Within Santander,

SCF accounted for 5% of the

Group’s total workforce and generated almost 8% of the bank’s

total profits. The largest market

remained Germany. (See Exhibit 3 for SCF’s financials.)

The European Market for Consumer Finance

There are still big differences between European countries in

terms of consumer credit market size,

consumer credit to GDP ratios (penetration) and consumer

product mix. These differences are due to different

levels of market maturity, economic developments, local

regulations and cultural factors.

— Salarich

Consumer finance included any kind of lending to finance

consumer’s purchases outside of

mortgage for real estate. It was certainly not an invention of the

20th century. Stores in the 19th century

had offered sales credit to their regular customers; and pawn](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stepsforeffectivecaseanalysisadaptedfromharvard-230122015619-2c3ebb42/75/Steps-for-Effective-Case-Analysis-Adapted-from-Harvard-docx-20-2048.jpg)

![markets were emerging around the

globe. Should Santander move to operate in these new markets?

A manager at SCF had noted both

the promise and the challenge these new markets might pose for

SCF:

Some people look at GDP per capita to understand where

consumer finance will go. I look

at cars per inhabitant. In Brazil you have 4 times the population

than in Spain but the same

number of cars. Growth will come from emerging countries such

as Brazil, India, and China.

[See Exhibit 14 for some figures]. Yet they are very different

from the countries where we are

now. Before investing here we need to make sure that our core

business is strong enough.

The second challenge was in consolidation. Which functions

should be centralized in order to gain

efficiencies, and which should be left decentralized? A manager

noted:

711-015 Santander Consumer Finance

12

Inciarte managed to find all these new opportunities and make

the bank’s board accept

them. We identified four areas that need to be improved: stock

finance, client’s conversion,

payments’ collection, and insurance. The discussion is how do

we do that? Do we set up a

central department that tells local managers what to do or

should we hire them locally? Some](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stepsforeffectivecaseanalysisadaptedfromharvard-230122015619-2c3ebb42/75/Steps-for-Effective-Case-Analysis-Adapted-from-Harvard-docx-42-2048.jpg)

![/Palatino-Roman

]

/NeverEmbed [ true

]

/AntiAliasColorImages false

/CropColorImages true

/ColorImageMinResolution 150

/ColorImageMinResolutionPolicy /OK

/DownsampleColorImages false

/ColorImageDownsampleType /Average

/ColorImageResolution 600

/ColorImageDepth -1

/ColorImageMinDownsampleDepth 1

/ColorImageDownsampleThreshold 1.50000

/EncodeColorImages false

/ColorImageFilter /DCTEncode

/AutoFilterColorImages false

/ColorImageAutoFilterStrategy /JPEG

/ColorACSImageDict <<

/QFactor 0.15

/HSamples [1 1 1 1] /VSamples [1 1 1 1]

>>

/ColorImageDict <<

/QFactor 0.76

/HSamples [2 1 1 2] /VSamples [2 1 1 2]

>>

/JPEG2000ColorACSImageDict <<

/TileWidth 256

/TileHeight 256

/Quality 15

>>

/JPEG2000ColorImageDict <<

/TileWidth 256

/TileHeight 256

/Quality 15

>>](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stepsforeffectivecaseanalysisadaptedfromharvard-230122015619-2c3ebb42/75/Steps-for-Effective-Case-Analysis-Adapted-from-Harvard-docx-64-2048.jpg)

![/AntiAliasGrayImages false

/CropGrayImages true

/GrayImageMinResolution 150

/GrayImageMinResolutionPolicy /OK

/DownsampleGrayImages false

/GrayImageDownsampleType /Average

/GrayImageResolution 600

/GrayImageDepth -1

/GrayImageMinDownsampleDepth 2

/GrayImageDownsampleThreshold 1.00000

/EncodeGrayImages false

/GrayImageFilter /DCTEncode

/AutoFilterGrayImages false

/GrayImageAutoFilterStrategy /JPEG

/GrayACSImageDict <<

/QFactor 0.15

/HSamples [1 1 1 1] /VSamples [1 1 1 1]

>>

/GrayImageDict <<

/QFactor 0.76

/HSamples [2 1 1 2] /VSamples [2 1 1 2]

>>

/JPEG2000GrayACSImageDict <<

/TileWidth 256

/TileHeight 256

/Quality 15

>>

/JPEG2000GrayImageDict <<

/TileWidth 256

/TileHeight 256

/Quality 15

>>

/AntiAliasMonoImages false

/CropMonoImages true

/MonoImageMinResolution 1200

/MonoImageMinResolutionPolicy /OK](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stepsforeffectivecaseanalysisadaptedfromharvard-230122015619-2c3ebb42/75/Steps-for-Effective-Case-Analysis-Adapted-from-Harvard-docx-65-2048.jpg)

![/DownsampleMonoImages false

/MonoImageDownsampleType /Average

/MonoImageResolution 600

/MonoImageDepth -1

/MonoImageDownsampleThreshold 1.50000

/EncodeMonoImages false

/MonoImageFilter /CCITTFaxEncode

/MonoImageDict <<

/K -1

>>

/AllowPSXObjects false

/CheckCompliance [

/None

]

/PDFX1aCheck false

/PDFX3Check false

/PDFXCompliantPDFOnly false

/PDFXNoTrimBoxError true

/PDFXTrimBoxToMediaBoxOffset [

0.00000

0.00000

0.00000

0.00000

]

/PDFXSetBleedBoxToMediaBox true

/PDFXBleedBoxToTrimBoxOffset [

0.00000

0.00000

0.00000

0.00000

]

/PDFXOutputIntentProfile (None)

/PDFXOutputConditionIdentifier ()

/PDFXOutputCondition ()

/PDFXRegistryName ()

/PDFXTrapped /False](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stepsforeffectivecaseanalysisadaptedfromharvard-230122015619-2c3ebb42/75/Steps-for-Effective-Case-Analysis-Adapted-from-Harvard-docx-66-2048.jpg)

![/SVE

<FEFF0041006e007600e4006e00640020006400650020006800e

4007200200069006e0073007400e4006c006c006e0069006e0067

00610072006e00610020006f006d0020006400750020007600690

06c006c00200073006b006100700061002000410064006f006200

650020005000440046002d0064006f006b0075006d0065006e007

400200073006f006d002000700061007300730061007200200066

00f60072002000740069006c006c006600f60072006c006900740

06c006900670020007600690073006e0069006e00670020006f00

6300680020007500740073006b007200690066007400650072002

000610076002000610066006600e4007200730064006f006b0075

006d0065006e0074002e002000200053006b00610070006100640

0650020005000440046002d0064006f006b0075006d0065006e00

740020006b0061006e002000f600700070006e006100730020006

90020004100630072006f0062006100740020006f006300680020

00410064006f00620065002000520065006100640065007200200

035002e00300020006f00630068002000730065006e0061007200

65002e>

/ENU ()

>>

>> setdistillerparams

<<

/HWResolution [600 600]

/PageSize [612.000 792.000]

>> setpagedevice

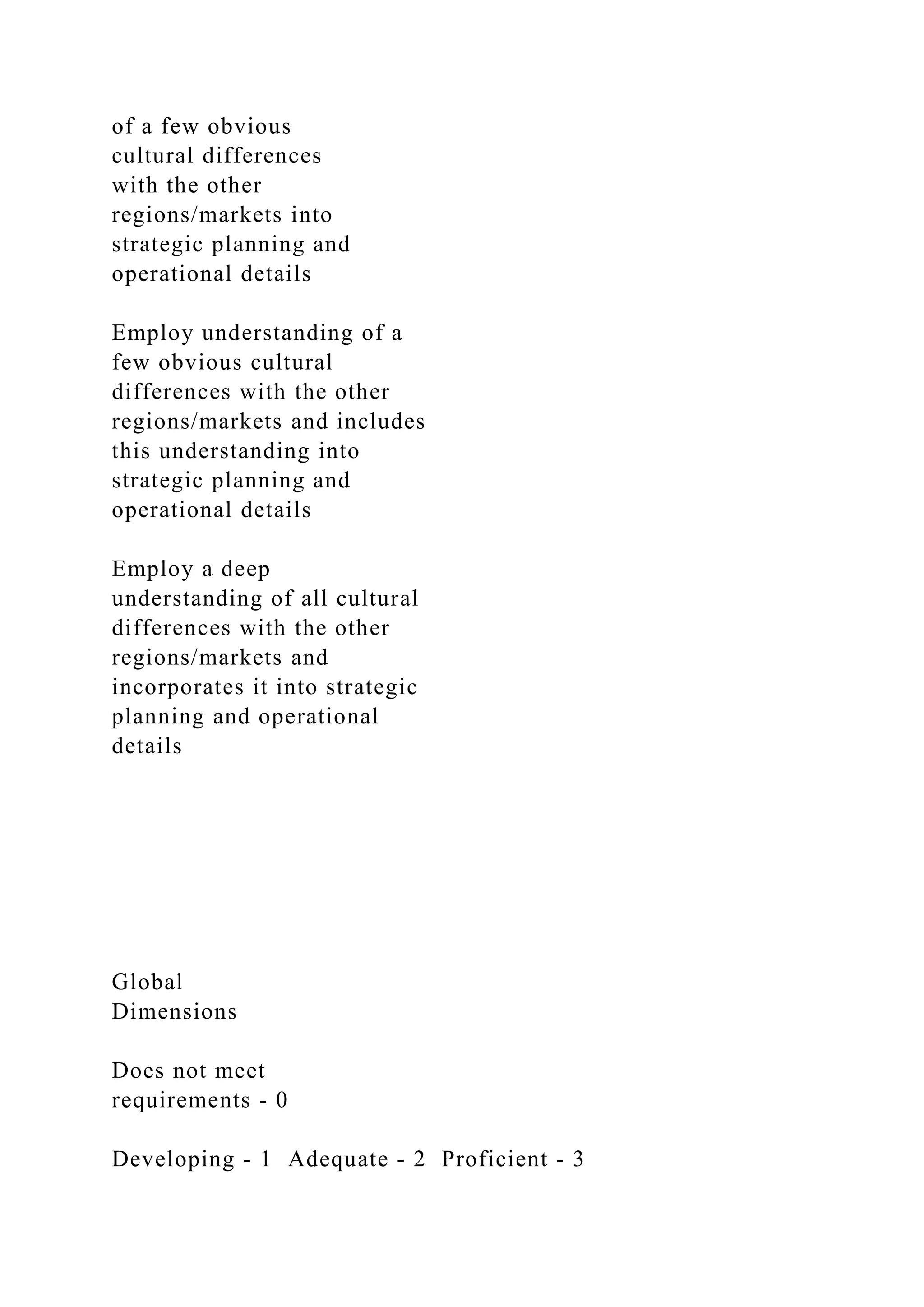

Appendix C: Global Orientation SLO Scoring Rubric

Global

Dimensions](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stepsforeffectivecaseanalysisadaptedfromharvard-230122015619-2c3ebb42/75/Steps-for-Effective-Case-Analysis-Adapted-from-Harvard-docx-72-2048.jpg)