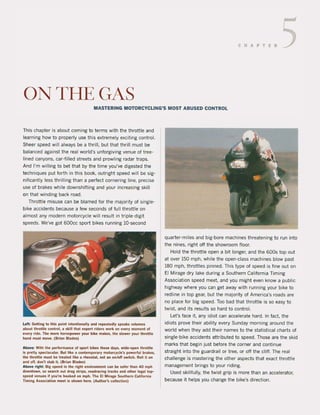

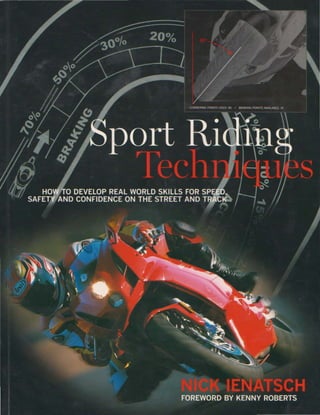

This document provides an introduction to a book about sport riding techniques for motorcycles. It discusses how motorcycle technology has advanced greatly, outpacing riders' skills. The book aims to strengthen riders' abilities by teaching techniques to ride safely yet quickly. It will cover topics like braking, vision, steering, acceleration, the environment, track riding, urban survival, and group riding. The goal is to help all riders, from beginners to experts, refine their skills and appreciate that proper techniques are important for performance and safety.

![Tune-up Time

Whcn did you last visi! the optometrist? Iryou'cc like most Amcricall.',

you have your eyes checkcd only when you break youe glasses, lose

your contacts or rail thc drivcr's liccnse eye exam. Theee you are, pos~

sihl}' riding with faulty cquipmcnt, a set ofeyes that arcn', truly seeing

eVl'rythillg t1l(~y ean. As a lIlotoTcydist, your lifc dcpcllds on your

ViSÎOll, ,~o 3n anuual cye eX311l might he one o[the best steps )'ou eall

take 10 extend YOUT riding career.

Many riders wcar glasses or conlacts while riding. Classes ean be a

hassle tn fit insiuc thc hdlllcl and arc an o!Jviols danger during a crash

1X.-ç3USC of tilde proximity 10 the eyes. Thcy present 31l0lhcr surfacc

fOf dirt and rlchris 10 seule Ijxm, aud another laycr 10 rog during mld

or wet wealher.

COnlacts wearers have found varying degrees of success, mostly

de]lCnding on how much wind enters their hdmets. One oflhe most

famous contacts~wearing roadracers is Freddie Spencer. He was

often photographe<:l wilh tape surrounding his face shidd for an extra

larer 10 protelt against wind entering his Arai. He wam't always able

to keep his lenses in place successfuH)', but that diffiCllty l:allle dur~

ing the stress of a soocc Grand Prix. when it's probably difficult to

relllelllbcr 10 blink. Street riders should find il casier.

One trui)' miraeulous solution for riders foreed to wear eorrel:tivc

lenscs has been lascr slIrgery that correcls nearsightcdncss and

astigmatisms. runderwent Ihis surgery at the beginning of1995 after

racing for six years with glasses, and the results continue 10 be ter-

fifie. Two things PUShl-d lIle lowanllascr surgcry.The !lrsl was a very

rain)' 1994 scason, whkh had lIle frequently clIrsing my foggy, wel

glasses. Second. my glasses lefl me with a cut on my cheek after I

crashed a lesl bike in Germany. The gash could have been myeye,

50 after a few Illonths of research, I gol lasered.

This hook isn'l a source for laser surgery information, but this sur-

gery is a tremendous solution for nearsighled mOlOrcycie riders. You

depend heavily on yonr eyes. wcar constraining headgear alld ride

in a wiml)", {lirl)', sOlllelimes wel environmenl. Iencollmgc you 10 look

into it. Who knows what perfeCI vision can do for you?

Again, astreet rider must scan the asphalt to check for

debris and bumps, while a racer can be more certain of

pavement consistency.

SELF-ANALYSIS

Since the eyes are so criticaI to our sport, it's important to

recognize the problems that stem from improper visual

habits. Failing to master this single skill can cause a wide

variety of riding problems. Among them are the following:

1. Running wide in a corner. If you had slow-motion video

of a rider going wide in a corner, you'd probably notice

that her eyes quit looking through the corner. Instead,

her eyes either got caught on something like a pothole or

rock, or failed to scan through the corner as the bike

entered it. Qnce again, keep your eyes moving ahead of

the bike.

Z. Hitting stationary objects. Target fixation is a simple term,

but it brings an ugly result. Arider's eyes get caught on

something like a pothole, car fender, curbing-and the bike

follows the gaze. Tearing your eyes off something that

draws your interest is like ripping Velcro apart-but it's a

skill worth mastering.

3. Being late on the throttle. Applying the throttle (lightly) as

early as possible after turning into a corner is a critical

aspect of riding weil. We will talk all about it in chapter 5, but

the reasen many riders are late on the throttle is their eyes:

They're simply not looking up the road far enough. No matter

how many times you've ridden through a corner, your brain

needs your eyes to reaffirm that the pavement does indeed

still exist and that your right wrist can begin to gently roll on

the throttle.

4. Being overwhelmed and surprised. Riders continuously

overwhelmed with speed are simply focusing too close to

their front tire. Distance slows things down and gives the

brain more time to deal with everything from an encroach-

ing car to an upcoming corner.

5. Entering a corner far toa slowly. While braking for a cor~

ner, it's easy to leave your eyes on whatever you were

using to gauge your speed and braking distance, and your

entrance speed suffers. You stay on the brakes too Jong

because you need your eyes to look into the corner to cor-

rectly gauge the corner's radius, pavement. etc. Isn't it

interesting to find that one of the main secrets to good

entrance speed is the eyes?

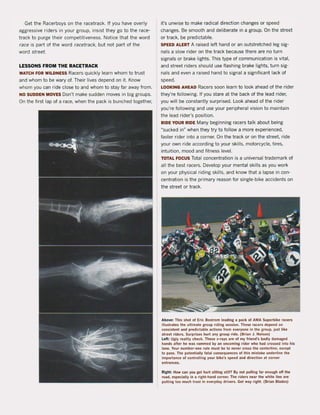

LESSONS FROM THE RACETRACK

CLEAN IS CLEAR The top professional racers visit their hel-

met representative between every practice for either a

face-shield cleaning or a completely new face shield. The

tuners take plenty of time making sure the bike's windscreen

is clean and smudge free. Everyone involved knows the

importance of giving the eyes the clearest view possible.

LOOK AHEAD OF THE COMPETITION Beginning racers soon

discover that if they stare at the rider they just caught. their

speed will match that rider's speed exactly. Racers learn to

look ahead of the rider they hope to pass, monitoring that

rider's place on the track with quick glances and use of

peripheral vision.

GET LASERED Getting rid of your glasses or contacts really

helps, especially in dusty venues or the rain. Laser surgery

eliminates the need for glasses and seems tailor-made for

racers.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sport-160320171219/85/Sport-Motorcycle-Riding-Techniques-32-320.jpg)