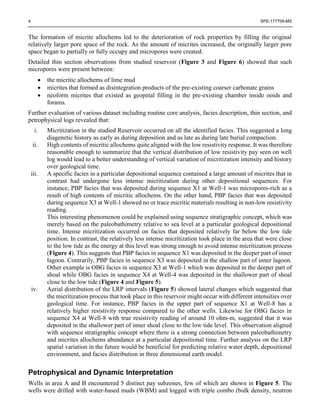

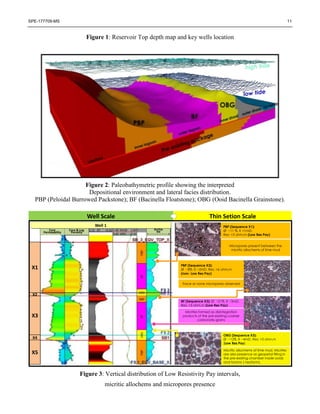

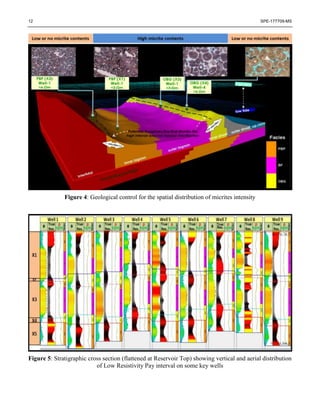

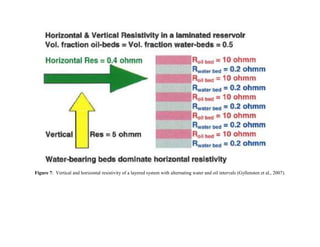

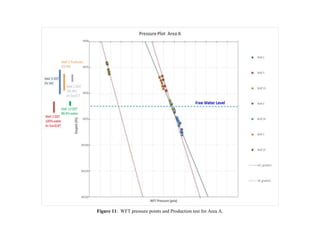

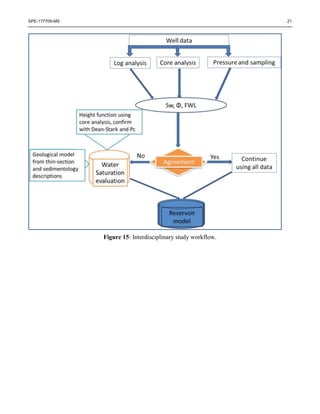

This paper discusses an integrated approach to characterizing water saturation in a low-resistivity carbonate reservoir in Abu Dhabi. Traditional resistivity-based analyses overestimated water saturation in this reservoir. The integrated approach combined resistivity logs, core analysis including NMR and capillary pressure tests, and production test data. It identified microporosity from thin sections and NMR as contributing to the low resistivity pay. The combination of multiple data sources reduced uncertainty and improved understanding of reservoir properties, saturation estimates, and reserves calculations compared to resistivity-based analyses alone.