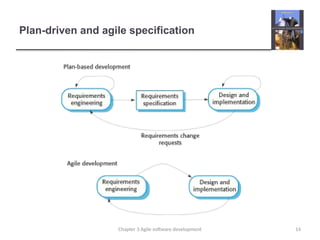

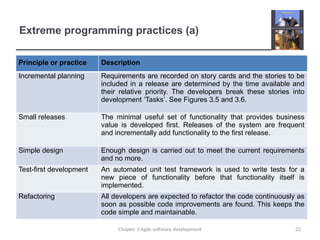

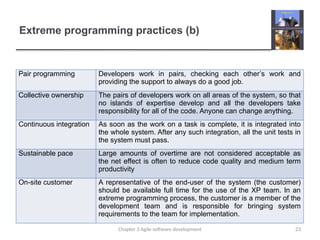

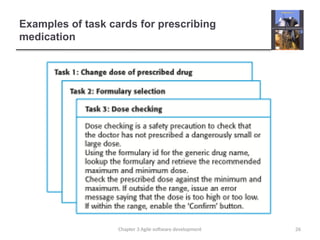

The document discusses Agile software development, emphasizing iterative progress, collaboration, and flexibility to meet changing requirements. It outlines various Agile methods such as Scrum and Extreme Programming (XP), highlighting principles like customer involvement and incremental delivery, along with common practices in Agile project management. Additionally, it addresses the challenges of scaling Agile methods for larger systems and the importance of maintaining existing software alongside new development.